1 Will it Bite?

Bloodsucking insects have been biting humans for countless thousands of years, but as our understanding of their different types has developed, one group has come to acquire a sinister notoriety far beyond their diminutive size. Today, the narrow-winged, thin-bodied, long-legged flies that pester us in the night or in marshy fields are almost universally called ‘mosquito’. This name is recognizable around the world in a wide number of languages: mosquito in English, Spanish and Portuguese, mosquit in Catalan, moustique in French, Moskito in German, Moschgieder in Deitsch (Pennsylvania German), mosgito in Welsh, muiscít in Gaelic, moskítóflugur in Icelandic and mushkonja in Shqip (Albanian). But ‘mosquito’ is a relatively modern appellation, appearing (in English at least) only at the very end of the sixteenth century. The bite victim, left rubbing a swollen welt, might wonder why it matters what we call the bug that bit, and why it should be at all important to distinguish it from other biters. The scientist provides the answer. It is not so much the prick given, or the blood taken, but the disease left behind after the bite that has defined mosquitoes and made them among the most vilified creatures on the planet. In this instance, it becomes supremely important what we call things, and how we distinguish them from one another.

Things were not always so. When the first ‘cave men’ fell victim to bloodsucking flies, they would no doubt have given their tormentors names – names to discuss them civilly, or to curse them by. These names are now hidden in the clouds of prehistory, and a study of biting insect names can only really begin with the first written texts, or at least those texts that are preserved.

The ancients of classical Greece and Rome made very unclear distinctions between the various sorts of small, biting flies. Aelian, writing in the second century, claimed that African biting flies were larger and more aggressive than those in the Mediterranean. The upside of this was that, although they attacked humans with greater voracity, they also helped to keep lions away. Like most classical authors, he does not give quite enough information to identify exactly which flies he is talking about. For several hundred years, observers refer to various small, nondescript biting flies, and names like empis, culex and conops are regularly bandied about.1 Unhelpfully, these names are also applied to other insects, which, from the context, are obviously not biting flies at all. Sometimes, it is virtually impossible to equate these archaic terms with modern names. Aristotle has been criticized for ignoring gnats, but this is rather unfair given that so many small insects are still, today, lumped together by non-specialists as just ‘bugs’. He knew well enough that some insects have their stings in front (for feeding) or behind (as a weapon) and that no two-winged insect (fly) had its sting behind, because these insects are too weak to sting with their abdomens. Pliny repeated that gnats had their sting at the oral orifice. Biting and stinging are still confused today.

Language scholars still struggle to interpret exactly what creatures appear in classical literature. A salutary example is shown by trying to understand the biblical plagues, rained down by a wrathful Old Testament God. The third plague is variously translated as one of ‘nits’ or ‘gnats’. These two very similar-sounding words in English may have similar roots, but they relate to entirely different creatures. The fourth plague is often referred to as a plague of flies, but ‘beetles’, and ‘wild beasts’ are also used in some understandings. The English entomologist John Obadiah Westwood was one of the first (1838) to suggest that it was actually a plague of ‘musquitoes’.2 His supposition was based on a knowledge of insect ecology, rather than linguistic expertise, but the debate is still ongoing. The Bible is one of the most intensively studied texts in the world and yet modern experts in history and linguistics still cannot agree exactly what was meant. To get an understanding of the names we now use for biting insects, we really have to start in the present (or at most in the past two or three hundred years), and work backwards, extrapolating as best we can until the linguistic threads are frayed and lost.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Naming insects has often been a vague process. We have general terms for those that are startling (dragonfly), pretty (butterfly) or inspirational (sacred scarab), or that are nuisance pests that attack homes (termite), crops (locust), timber (woodworm), food (housefly) or other human belongings (bookworm). Most insects are secretive, avoiding human contact, and have gone without precise names for millennia, until modern scientists began to catalogue them as part of their esoteric studies into biodiversity.

Bloodsucking insects, though, do often have good, solid common names; this is because they came to the notice of the humans they bit very early on in history. Most of these names show folk origins from simple word roots. Thus, in English alone we have a veritable wealth of names to choose from: flea (familiar jumping insects); louse (also sometimes nit); bedbug (bites us in our beds); mite (a widely used alternative for flea, louse and others); tick (bloodsucking arachnid); cleg, stout, gadfly and breeze (all bloodsucking flies of stock animals and their herders); horsefly (also bites their riders); stablefly (also bites the grooms); sandfly (lives in sandy places); deerfly (also bites their stalkers); sheep ked (on sheep, and the occasional shepherd); blackfly (some are also grey); and, in North America especially, the jauntily named no-see-um (virtually any tiny, biting fly).

Across the world, these same, or similar, bloodsuckers have national, local and dialect names aplenty. In various parts of England, for example, residents are bothered by buers or buvers (the northeast), mingins (Norfolk) and nudges (Cheshire).3 Traditionally, the more delicate, flimsy, diaphanous bloodsuckers have been called, in English, midge or gnat. These two lovely, short, monosyllabic words, which can be sneered or spat out, tell us much about the opinions our ancestors had for these unlovely insects.

‘Midge’, descended through the Old English mycg, Old Saxon muggia, Old High German mucca and Norse my, seems to be a corruption from the Latin musca – ‘fly’. J.R.R. Tolkien immediately evoked the buggy itchiness of the swamplands by having his Lord of the Rings (1954–5) hobbit heroes trudge through the Midgewater Marshes on the first leg of their epic journey through Middle-earth. ‘There are more midges than water!’ protests an irate Peregrin Took. Thomas Hardy’s unnamed woman-of-the-road, in his poem ‘A Trampwoman’s Tragedy’ (1903), was bitten ‘by every Marshwood midge’. In Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1886), the narrator David Balfour is ‘troubled by a cloud of stinging midges’.

‘Gnat’ comes from the Old English gnaett, Low German gnatte and Middle Low German gnitte, which some etymologists have also linked to the nit. Gnat is possibly a shortening of one of the words the ancient Greeks used for various biting flies: conops (κωνωψ), literally ‘cone-faced’, alluding to the insects’ pointed heads.4 Unfortunately, the modern fly genus Conops has nothing to do with pointy-faced bloodsuckers, but refers instead to a group of pretty, wasp-like bee parasites. But there is an ancient echo in the language, since a couch or bed protected by a mosquito net was, in Roman times, conopium, from which we get canopy and canapé (covered bread).5

Gnat, even more than midge, seems to have been used historically in a much more diffuse way than some of the other bloodsucker terms, and is most often applied to the flickering specks of insect life hovering about in the gloaming or capturing glints of sunlight above water. Thomas Hardy evokes a slightly more benign scene in Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), capturing the moment of the setting sun’s slanting rays when ‘Gnats, knowing nothing of their brief glorification, wandered across the shimmer of this pathway, irradiated as if they bore fire.’ Likewise, Dickens uses the imagery of ‘a thousand gossamer gnats’ as dusk falls in A Tale of Two Cities (1859), and in Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) contrasts ‘the bee . . . humming of the work he [sic] had to do’ with ‘the idle gnats, forever going round and round in one contracting and expanding ring’. Gnat was also the regular term of choice for William Shakespeare, who used them to evoke a sense of hazy days, rising thermals and slanting evening light: ‘When the sun shines, let foolish gnats make sport’ (The Comedy of Errors, c. 1594), ‘Whither fly the gnats but to the sun’ (Henry VI, Part 3, 1595), and ‘Is the sun dimm’d that gnats do fly in it?’ (Titus Andronicus, 1594).

‘Gnats’ and ‘midges’ are still flying, although these terms are slightly tainted with archaism. ‘Mosquito’, on the other hand, is a name very much of the moment; a modern word, with more precise scientific meaning and portent. The word derives from the Spanish and Portuguese diminutive of mosca, or fly (Latin musca again), and is a much more modern construct (1583, according to the Oxford English Dictionary). Musket, originally a crossbow firing stinging bolts, then a hand-held gun, appeared from the same root around the same time (1587). It’s tempting to suggest that this is no accident, but fits precisely with the imperial aspirations and moves of the major European powers, out to mosquito-infested south Asia, Africa and the New World at exactly this time, exchanging important words as increasing trade, competition, conflict and conquest brought them closer together.

Slightly sketchy gnats from Ulisse Aldrovandi’s De animalibus insectis (1637).

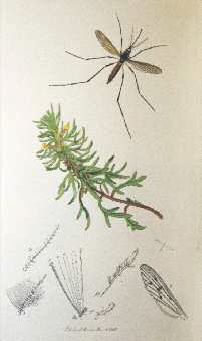

| Culex guttatus, the white-spotted gnat or mosquito, from John Curtis, British Entomology, vol. VIII (1839). Curtis sold his British Ento mology to subscribers in parts issued every few weeks. His sales, even of disreputable creatures like mosquitoes, relied on exquisite engraving skills. |  |

MOSQUITO ORIGINS

Today, the word ‘mosquito’ is technically applied by entomologists to just one family of midge/gnat biting flies, the Culicidae – from the Latin culex, one of those several words widely used in ancient writings to signify a biting gnat. Mosquitoes are distinguished from similar long-legged and long-winged relatives by a combination of the particular structure of their bloodsucking mouthparts, some distinctive wing vein patterns, the microscopic dusting of sometimes prettily arranged scales on body, legs and wings, and a fringe of long scales along the trailing edges of the wings. Under the microscope, mosquitoes are often revealed as delicately painted masterpieces of biological creation. Some, like the bizarrely foot-tufted Sabethes belisarioi, are truly exquisite in colour and startling in form.

Anatomically suspect gnats, 1763. Until the regular use of the microscope, general confusion of gnats, midges and other biting bugs was widespread, as was any clear understanding of their structure.

If it were not for their unpleasant biting habits, mosquitoes might well have been chosen by early naturalists (very often members of the clergy and wealthy gentlemen of leisure) seeking instruction and wonder in the designs of God and wanting to fill their cabinets of curiosity with beautiful objects. Instead, brightly coloured beetles and butterflies became the major focus of their inquisitive entomological minds. The lack of admiring interest in gnats and midges did nothing to dispel the general derision heaped upon them. And, although they were well known for their biting habits and their spectacular (almost supernatural) transformation from watery larva to aerial adult, a true appreciation of their diversity had to wait until the 1890s.

| The North American Tlingit craftsman who made this ‘mosquito’ mask around 1840 imagined a bird-like beak for the insect’s proboscis. |  |

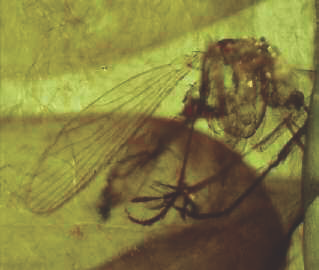

The first human–mosquito contacts are now lost in the fogs of prehistory. However, it is certain that mosquitoes started to appear long before there were any humans. As with all insects, their fragile, easily digested, easily destroyed bodies mean that the mosquito fossil record is far from complete. However, beautifully preserved remains have long been known. In his treatise on natural theology, The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation (1691), the prominent English naturalist John Ray considers:

|

A North American Kwakwaka′wakw mosquito mask. |

diaphanous fossils [ambers] preserved in the cabinets of the great duke of Tuscany . . . and other repositories . . . of the admirable diversity of bodies included and naturally imprisoned with them, as flies, spiders, locusts, bees, pismires [ants], gnats . . .6

At the time, the nature of amber as fossilized tree sap was not fully understood, but Ray appreciated that these tiny insects, together with seeds, hair and drops of liquor, proved that it had ‘been once in a state of fluidity’.

At present (2011), the oldest fossil mosquitoes we know are Paleoculicis minutus, trapped in Cretaceous Canadian amber 79.5–76.5 million years ago, and Burmaculex antiquus in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber, from 100–90 million years ago.7 Both are distinctly different, in some of their minute body structures, from all known modern and previous fossil mosquitoes, but they share the key characters of wing venation, scale patterns and mouthparts, and so they are, indeed, truly mosquitoes. Most important, the mouthparts are well preserved in both specimens and it is clear from their forms that they were adapted for drinking vertebrate blood.

It is now reckoned that mosquitoes evolved much earlier than 100 million years ago. A non-biting sister group of tiny flies, the Chaoboridae (sometimes called phantom midges), are more widely known, from abundant fossils up to 187 million years old, so it is likely that mosquitoes appeared at least as early as this. This suggestion is reinforced by using the complex techniques of protein molecular analysis (similar to DNA sequencing).8 By examining the cocktails of specialist blood-digesting enzymes found in modern mosquitoes, scientists have extrapolated evolution backwards. They can show that Old World and New World species started to evolve along separate genealogical lines about 95 million years ago, concomitant with the break-up of Gondwanaland into modern continents, and that the main lineages of today’s mosquito species started to diverge at least 150 million years ago. A general precursory bloodsucking mosquito-like group must have been present long before this.

|

Paleoculicis minutus, trapped in Canadian amber for about 80 million years. Even then, mosquitoes had vertebrate-piercing mouthparts to suck warm red blood. |

These primeval mosquitoes were already adapted to vertebrate bloodsucking, and, though scant, their fossils occur alongside well-preserved remains of birds, primitive mammals, marsupials, lizards, snakes, turtles, crocodilians and dinosaurs, prompting the question as to what hosts they were feeding on. In his science fiction novel Jurassic Park (1990), Michael Crichton gave an answer: they were drinking dinosaur blood. In his successful book, DNA was extracted from host blood in the guts of amber-bound mosquitoes, and used to genetically engineer new living dinosaurs, which then roam the eponymous prehistoric theme park for paying visitors to gawp at.

The scientific possibility of extracting and sequencing blood DNA from fossilized mosquitoes remains a fiction, but Crichton’s idea is based in a reality becoming more and more true as time (and technology) advances. DNA and protein sequencing have already been used on the host blood collected from the guts of living mosquitoes, enabling researchers to confirm what types of animals (including humans) they have been feeding on, and even to identify the different species of mammals and birds from which the blood meals were taken. There have been suggestions that forensic science might make use of this technique, in seeking to identify a criminal or link someone to a crime scene, by identifying their blood in the digestive tract of a mosquito found nearby. This process has already begun, and in 2005 the technique was used to aid a Sicilian murder investigation.9

Today there are approximately 3,500 mosquito species known from around the globe; these are variously described and classified in the scientific literature of learned journals and monographs, and with reference specimens in the world’s museums. New species are being described all the time, as entomologists continue to explore the deep tropics. And, although this is not the place to go into too much detail, it is important to give a few details of mosquito classification, because different mosquitoes have had gravely different effects on human history.

Mosquitoes belong to the fly family Culicidae, which itself is divided into three subfamily units. The Toxorhynchitinae, with about 80 species in the single genus Toxorhynchites, are large (about 19 mm/¾ in long, with a 24-mm/1-in wingspan) and often brightly coloured in metallic blue or green with tufts of red or white scales projecting from their tail ends. They get their name from toxon (the Greek τοξον, for bow or archer) and rhungchos (ρύγχος, snout), because their large, pointed mouthparts are strongly curved backwards in a characteristic bow shape. Some authors have suggested toxo comes from toxa (Greek τοξα or ‘arrow’), but this is more likely a projection of the idea that mosquitoes must have sharp beaks. However, the curved proboscis of Toxorhynchites is useless for bloodsucking: it cannot pierce skin, and these giant mosquitoes, ferocious though they may look, do not bite. Instead, they drink only nectar and other plant-liquid secretions. Consequently, they are of no medical importance and are relatively poorly studied.

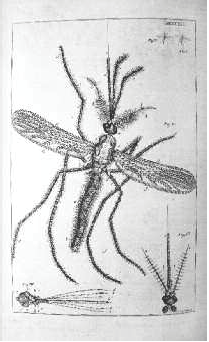

By 1758 the Dutch microscopist Jan Swammerdam had a clear understanding of insect anatomy.

Under the microscope less than 50 years later, in 1806, the fine details of the immature and adult stages of mosquitoes are becoming clearer.

The Anophelinae, with roughly 450 species in three genera, most of them in the large genus Anopheles, are definitely bloodsuckers. Anopheles species occur worldwide, and some of the most important and best known include Anopheles gambiae and An. funestus in Africa, An. maculipennis in Europe, An. freeborni and An. quadrimaculatus in North America, and An. culicifacies in India and the Middle East. Identification guides, usually intended for experts examining pinned or pickled museum specimens, point out that Anopheles mosquitoes have long palps (thin feelers attached to the mouthparts), often spotted or speckled wings (caused by block arrangements of dark-coloured scales), only a single sperm-storage organ in the female abdomen, and a shortened middle lobe of the salivary glands. The most distinctive feature in living adults is the 45-degree head-down, tail-up pose they adopt, both when resting and when supping blood. It is this unusual angular resting position that has proved to be one of the most significant messages to get across to the public, and it is highlighted again and again on warning posters and in medical pamphlets.

| The Mosquitoes’ Parade, 1900, a piece for piano by Howard Whitney. With their beaked bird-like faces these mosquitoes look positively benign, probably a deliberate ploy by the publishers. |  |

There is something almost balletic about this stance, emphasized by the long back legs held out into the air. The Israeli artist Miri Chais uses this characteristic pose to create a series of delicate acrylic desktop mosquito sculptures. Each comes complete with interchangeable wing patterns featuring, among other designs, atomic and molecular symbols, the nuclear disarmament (‘ban the bomb’) logo and a portrait of disgraced US stockbroker Bernard Madoff (perhaps being portrayed as a bloodsucker) surmounted by pigs and the slogan ‘In God we trust’.

The largest mosquito subfamily, by far, is the Culicinae, with something approaching 3,000 species in about 35 genera, the largest of which are Aedes (about 1,000 species) and Culex (about 800 species). Among the better-known species, the vexatious Aedes vexans occurs worldwide in subtropical and temperate zones and Ae. aegypti is a global tropical species, while Ae. africanus is African and Ae. albopictus Southeast Asian. Culex pipiens is completely cosmopolitan, occurring throughout the globe, C. quinquefasciatus is pan-tropical and C. tarsalis North American. Again, those monographs and identification guides concentrate on abstruse characters like the short palps (at least in the females), less speckled and more evenly dusky wings, two or three abdominal sperm-storage sacs in the female, and the long middle lobe of the salivary glands. But the most easily spotted sign of a culicine mosquito is its body stance – strongly contrasting with Anopheles, it sits parallel to the surface on which it is resting or the skin through which it is biting. When Russian artist Valery Chaliy created a huge metal mosquito sculpture from salvaged car and bulldozer parts, it was the culicines from the local quagmires of Noyabrsk that provided the threatening inspiration.

Made of salvaged car parts, the Russian mosquito statue by Valery Chaliy was inspired by the local Culex mosquitoes, which hold their bodies parallel to the surface on which they are resting or biting.

Today, the naming of insects (indeed all animals and plants) is governed by complex codes of scientific agreement, and great time and effort is expended on making sure that names are not muddled or duplicated. New species are constantly being discovered and named by entomologists. This is no mere counting and numbering process, and naming a new species is often given the same care as naming a child. The rules for making scientific names are dictated by certain basic conventions of Latin and Greek grammar, the need to avoid offence and frivolity, and particularly the avoidance of names already in use. Once these are grasped, entomologists are ever-ready to rise to the challenge of producing new names with creativity and wit. A very brief survey of mosquito names provides us with: Aedes condolescens, Ae. excrucians, Ae. intrudens, Ae. insolens, Ae. irritans, Ae. lugubris, Ae. tormentor, Ae. vexans, Anopheles atropos (Atropos was one of the three life-taking Fates in Greek mythology), An. hectoris, Culex abominator, C. horridus, C. inadmirabilis, C. mortisans, C. perfidiosus, C. sphinx (after the winged monster of Greek mythology), Haemagogus lucifer and Phoniomyia diabolica.10

|

A mosquito cuddly toy. A strange reversal, perhaps, in which the human child becomes the biter and chewer, rather than the bitten? |

The prominence of mosquitoes, a relatively small group among a horde of other two-winged bloodsuckers, appeared, crystallized almost, as a detailed understanding of their life history and ecology arose, and as their associations with disease were unravelled. Where once a gnat or midge was any small, annoying speck of animated malignant life, to be swatted, cursed or stoically tolerated, ever-finer distinctions between the different types became necessary to deal with the medical and biological impacts these irritating insects would have on humanity. These distinctions were not merely the preserve of specialist entomologists; they became vital tools in the work of the propagandists charged with informing the general public about mosquito dangers, and eradicating the mosquito menace which plagued not just our persons, but our very civilization.