2 Why Drink Blood?

There is something so light and airy about mosquitoes, with their narrow wings and the stilt-like gantry of their legs, that the notion of them digging deep into relatively thick and tough human skin to suck out blood seems altogether absurd. It is patently obvious that mosquitoes do bite, but why, and how, are questions intimately linked to an understanding of the complex human–bloodsucker ecology that has evolved. Ultimately, it is the why and how that has shaped the disease importance of mosquitoes.

The human body fights blood loss through the anti-trauma strategies of vasoconstriction (narrowing of the blood vessels) and clotting, because blood is, quite literally, vital to our existence. So, too, others try to extract it for their own ends. This battle between host and blood-thieves has escalated through evolutionary history and the arms race between mosquito aggressor and human defender has given rise to all the physiological and behavioural properties that make mosquitoes so important today.

In the vertebrate body, blood is transport. To use a well-worn metaphor, the arteries, veins and capillaries through which it flows are the highways and byways down which gases, nutrients and bodily products are carried. Blood has two key properties that make it such a useful and versatile bodily substance: it is a mobile fluid (human blood is about 50 per cent water) and it is rich in proteins – complex, specialized biochemicals that carry nutrients and carbon dioxide in blood serum (the fluid part) or that make up the haemoglobin in the oxygen-carrying red blood cells. These special qualities also make it highly sought-after by bloodsucking insects.

Protein richness is blood’s major attraction. Protein is usually the limiting factor to growth in an animal. Herbivores spend all day chewing or grazing to extract the precious protein from vast quantities of cellulose and carbohydrate. Predation (usually hunting other insects) has evolved in all the major insect groups, because it is a much easier way of getting hold of protein. It comes at a price though – hunting each other is dangerous and prey is liable to fight back, with potentially damaging or fatal consequences. Vertebrate protein is readily targeted by insects; they scavenge vertebrate carrion or fallen antlers, nibble on fur and feathers moulted in nests, or suck blood from living vertebrates.

Strictly, mosquitoes are not solely blood-feeders, because like all insects they do virtually all of their feeding, and certainly all of their growing, as larvae; just like other insects, they manage to derive enough protein during this stage for metamorphosis into adulthood. It is the adults that then suck the blood. But this late-taken food is no mere energy-giving fuel for flight and other daily activities – that is provided by plant nectar. Incidentally, the flower-visiting habits of mosquitoes are often unappreciated, though in Canada Aedes nigripes is well known as a pollinator of arctic orchids.1 Instead, there is a vital growth stage that the blood nourishes, even though the flies’ bodily growing may have stopped: the growth and maturation of mosquito eggs. A very few mosquitoes, the Toxorhynchitinae for example, with their non-biting, curved mouthparts, lay eggs without a blood meal, a situation called autogenous development. They derive all the necessary nutrition for egg laying during their protein-enhanced larvahood, when they eat other mosquito larvae. This is a perfectly good way of acquiring protein, although there are always the associated risks of a predatory lifestyle. Most mosquitoes, though, go through anautogenous development, and cannot lay eggs unless they have that vitally important vertebrate blood meal. It is as if they take a nutritional gamble; they get through the larval stage quickly and easily (without the risks associated with being a predator), but defer full egg-laying ability until they have had a nutritional top-up from vertebrate blood.

Small insects biting large vertebrates brings its own problems of size inequality, but dangerous head-to-head face-offs are avoided by adopting the sneak-attack approach that pinches just an inconsequential drop of blood. Except that it is usually not a drop of blood, it is a suck, because blood’s flowing dynamics make it ideally suited to tubular sucking mouthparts rather than chewing jaws.

THE MECHANICS OF SUCKING

The roll call of bloodsucking insects testifies to blood’s excellent suitability as potent nourishment. Indeed, haematophagy (feeding on blood) has appeared in insects on at least 21 separate occasions through ancient evolutionary history: lice, bugs (bed-bugs and three other groups), fleas, flies (mosquitoes and thirteen other groups) and in Calyptra, a small genus of dull brown moths. All of these insects have stabbing and sucking mouths.

The insertion of the mosquito’s snout into human skin is a delicate operation. What seems already an impossibly thin beak is mostly protective sheath, surrounding the inner stylet lance that does the penetrating. With the advent of good light microscopes in the nineteenth century, structures like the mosquito proboscis were revealed to an awe-inspired populace, rivalling the engineering marvels of the age. In 1854, the wonderfully named Jabez Hogg wrote The Microscope: Its History, Construction, and Application. Many such titles appeared around this time, but Hogg’s tome is particularly noteworthy for its size (500–800 pages dependent on the edition), its longevity (over 30 years in print) and its equally Dickensian-sounding illustrator, Tuffen West. Accompanying one of West’s excellent engravings of a mosquito head, Hogg pontificates:

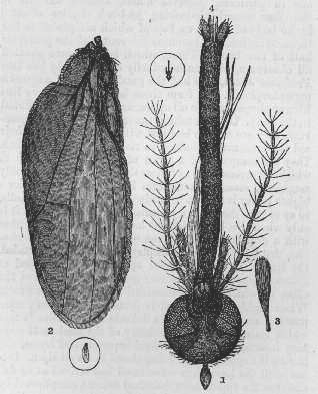

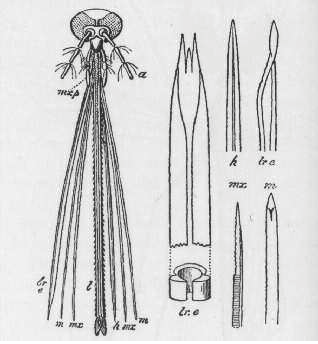

| The device that does the biting. A gnat tongue from Jabez Hogg, The Microscope (1854). |  |

The sting of the gnat (Culex pipiens) is well known; although the insects themselves, so very rapid in their movements, are so much dreaded that very few people care to examine the delicacy and elegance of their forms. The sting is very curiously contrived . . . and inclosed [sic] in a sheath, folds up after one or more of the six lancets have pierced the flesh.2

Leaving aside Hogg’s confusion of biting and stinging, his choice of words (my italics) clearly indicates a reverential wonder, even, for this despicable, bloodsucking device. West’s accurate illustration, and Hogg’s careful description, are as valid today as a century and a half ago. Those sheathed lancets have evolved from primitive appendages possessed by the ancestral arthropods that gave rise to all modern insects, and although wholly dissimilar in form and function, the various dissected parts can be identified and compared to the biting and chewing jaws in other insect groups.

As the mosquito pushes its mouthparts into the skin, the sheath splits open at the front and folds backwards, allowing the penetrating parts to slice down into the flesh. This needle weapon is not a simple dart, but is made up, as Hogg notes, of six interlocking rapier blades. Four of these (two mandibles and two maxillae, in entomological jargon) are sawtoothed at their tips and it is by rapid, back-and-forth movement of these that the mosquito digs through the dermis. One of the inner blades, the hypopharynx, has a narrow tube running down it, through which lubricating saliva is injected. The final, most important, mouthpart is the hollow labrum, the straw-like tongue at the centre, through which the blood is sucked up.

| The Victorian delight in the wonders of nature fully extended to the surgical precision of the mosquito’s dastardly biting equipment. |  |

Sucking human blood is not as easy as it might seem. It’s certainly a lot more complicated than the Disney/Pixar movie version in A Bug’s Life (1998), where the tipsy mosquito orders ‘Hey bartender! Bloody Mary, O-positive’ and is presented with a huge red glistening droplet, which he drinks down in one suck through his long, pointed nose before collapsing, comatose, on the floor.

Even without a full medical understanding, everyone has heard of blood pressure. There may be some mystery behind the exact workings of the sphygmomanometer, the tight arm-cuff device pumped up by the physician, or confusion as to what the millimetres of mercury actually represent, but there is a general awareness that the blood is pumped by a muscular heart, and that it courses, under mains pressure, through veins and arteries.

At first, it may seem foolish for such a tiny insect to attack the high-pressure blood system of a being roughly 100 million times bigger than itself. This certainly gives rise to some odd expectations, perhaps best represented by Gary Larson’s cartoon in which two mosquitoes have landed for lunch and one is inflated like a balloon. ‘Pull out, Betty! Pull out! . . . You’ve hit an artery!’ implores the other. It’s a nice touch that Larson uses a woman’s name for his six-legged blood-pressure victim, given that, of course, only female (egg-producing) mosquitoes suck blood.

One of the first problems a hungry mosquito has to contend with is not blood pressure, but blood clotting. A tiny pinprick to the skin will draw a relatively large scarlet droplet. But the cut does not stay open for long. A physiological cascade of biochemical reactions quickly seals the hurt with a clot. Human blood-clotting mechanisms are complex, but because of their medical importance, they are well studied. At its simplest, damage to even the smallest capillary in the skin exposes signal proteins (notably von Willebrand factor) to the blood. These recruit clotting chemicals circulating in the blood serum, particularly collagen (a large protein molecule) and the science-fiction-sounding ‘factor VIII’. At the scene of the damaged blood vessel, collagen fibres start to clog the wound, and tiny, circulating blood cells called platelets bind to them, in their turn releasing stored granules of further signal chemicals to activate more platelets. The combination of platelet bricks and collagen mortar easily and quickly seals the leak. And it is quick – initiated in a fraction of a second.

With all its digging and cutting (it may take several deep probes to find a suitable blood capillary), the mosquito’s bite is, surprisingly, far from a neat hypodermic needle insertion. Tiny though the wound may be, the multiple sawing and stabbing is enough to set off the human body’s clot reflexes, and, by all events, the labrum sucking tube ought to be quickly blocked by the usual crowding platelet clumps. Mosquitoes are ahead of this defence though. The injected saliva contains an anti-clotting chemical to usurp the platelet tumble. The blood flows free.

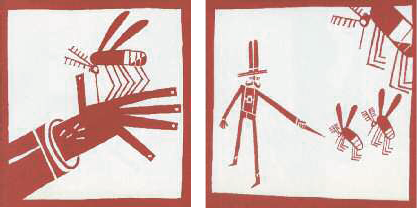

The vampire slayer versus the mosquitoes, from Mosquito by Dan James (2005). It would be unfair to prospective readers to give away the book’s ending; let’s just say that in this case, the mosquitoes do not get swatted.

The unwary victim does not usually notice the stab. Mosquitoes have evolved to get in quickly, take a small meal, and escape. The ideal time seems to be between 2½ and 3 minutes – any less and the blood meal is not worth the risk taken by the mosquito; any more and the pain of the drill is likely to be registered by the victim, with fatal results for the insect.3 During this typical 2½ - to 3-minute mealtime, the female mosquito sucks up a stomachful of blood. This is not a passive filling, powered by the host’s blood pressure, but an active sucking, expedited by two muscular pumps, one in the head, one in the thorax. As the mosquito feeds, her abdomen expands and her previously slim grey body becomes an ominously bloated translucent red.

VAMPIRE BUGS

There is something primordially unnerving about bloodsucking creatures. Human history is littered with dark tales of vampirism and ceremonial blood drinking. The gothic horror genre is well populated with vampire bats, werewolves and other bloodthirsty human/animal intermediates. In the real world, there is a natural revulsion associated with fleas, lice, leeches and various other parasites that feed on human blood. Part of this is, no doubt, through association with filth, disease and danger (real or imagined), and part must be an innate resistance to being eaten alive. Except when populating teen romance novels, creatures that drink human blood are universally reviled. It is no surprise that some of this unease gets passed on to mosquitoes.

Heavy rock band Pearl Jam seem to accept their sated ‘Red Mosquito’ with a stoic fatefulness. They blame the Devil for the mosquito’s bites. The stolen drop of blood that colours the fly, now bright red, is just a cunning reminder that he is out there, waiting, and the punctures in the neck are his way of letting you know he’s hovering just out of sight. Similarly, Cali fornian band Queens of the Stone Age used almost cannibalistic overtones in their ‘Mosquito Song’. First, the mosquitoes come to suck blood until all that’s left is skin and bone. Then, after references to being bitten on feet and legs comes imagery of butchery and cookery. Eventually, it is not clear who is eating whom alive. Is it the mosquitoes? Or the dark narrator? Whichever, the song ends with a fine summary of human blood availability – to them, we’re all just living food.

This vampirish, walking food aspect of mosquito hunger is also part of the murky, simmering gloom of John Updike’s poem, ‘Mosquito’:

I was to her a fragrant lake of blood

From which she had to sip a drop or die

A reservoir, a lavish field of food4

One vampire book that features the flies is the fairly obviously titled Mosquito, by Dan James.5 This curious but beguiling, wordless graphic novel follows the journey of a vampire-hunting explorer who is sent money, a map and Polaroid pictures of dead bodies from South America. Not knowing if this is a hoax or a mystery, he sets out to destroy the beast. At one point he is bitten by mosquitoes, and a final twist involves the vampire sucking out the blood from the mosquitoes, before releasing them again.

On a slightly lighter note, Bill Waterson’s cartoon six-year-old, Calvin, was right to run away from mosquitoes, even if overwrought and confused as he screams: ‘Vampire bugs! Run for your life!’

Blood is imbued with great significance across many human cultures. Various religious groups, notably Jehovah’s Witnesses, refuse to accept blood transfusions as this is, to them, analogous to eating blood, a nutrient expressly forbidden by the Bible. Terms like blood brother, blood relative, bloodline, blood money and bloodthirsty carry weight well beyond the biological measure of a red bodily fluid, and hark back to a time when blood was seen as the very liquor of life. It should really be no surprise that humans are wary of any animal, whether vampire bat or mosquito, trying to steal it.

The translucent body of the mosquito reveals its stolen blood cargo.

JUST A PINPRICK

The mosquito takes only a minuscule volume of blood. It is not even a drop, merely a tiny bit of a drop. A large mosquito will usually imbibe 1–5 mg, that’s 1–5 thousandths of a ml (1–5 thousandths of around 0.034 fl. oz), although up to 8 mg is recorded.6 For an adult human, with about 5 l (1.3 US gal./1 imp. gal.) of blood flowing through his or her body, this is roughly 1–5 five-millionths of total blood volume; a truly trivial amount. In his short poem ‘The Mosquito Knows’, D. H. Lawrence neatly sums this up:

The mosquito knows full well, small as he is

he’s a beast of prey.

But after all

he only takes his bellyful,

he doesn’t put my blood in the bank.7

We can, perhaps, forgive Lawrence for not realizing that only shes rather than hes will be taking the bellyfuls.

It may only be a few five-millionths of our blood volume that is taken, but anyone who has been bitten by a mosquito, and then vengefully struck it down, will have noticed the dramatic discrepancy between the apparently tiny body of the living insect and the large smear of blood its remains leave behind. D. H. Lawrence returned to the subject of mosquitoes to write his beautiful masterpiece of evocative poetry, called simply ‘The Mosquito’. It starts with the poet’s thoughts on the fly’s long legs and secret mode of attack:

What do you stand on such high legs for?

Why this length of shredded shank?

You exaltation?

Is it so that you shall lift your centre of gravity upwards

And weigh no more than air as you alight on me,

Stand upon me weightless, you phantom?

And, after the unequal combat, it finishes with the surprise:

Queer, what a big stain my sucked blood makes

Beside the infinitesimal faint smear of you!

Queer, what a dim dark smudge you have disappeared into!8

Yes, it is surprising, and slightly disturbing, what 1–5 mg (about 0.000035–0.000176 oz) of blood looks like. It was deliberately meant to disturb passers-by who noticed smeared red blobs splashed across illuminated adverts along the main streets of Atlanta, Georgia in the summer of 2010. It looks as if real mosquitoes have crashed into the brightly lit billboards, and fake wings carefully cut out from fine netting are stuck down amidst the splashes. The artist (or prankster) is unknown, but images and awareness spread on an appreciative internet. Part of the uneasiness about squashing a full mosquito is the fact that it is our own blood we are smearing. American writer and poet Brad Leithauser puts it very aptly:

The lady whines then dines, is slapped and killed

Yet it’s her killer’s blood that has been spilled.9

Distasteful as the swatted mosquito and its spilled blood cargo may be, the blood loss itself is virtually nothing to the human victim. What is noticed, however, is the painful red bump that appears a few minutes after the bite. The lump, sometimes several centimetres across in susceptible people, is not caused by the removal of that infinitesimal amount of blood, but by an allergic reaction – the body’s immune system responding to the injected mosquito saliva, with its cocktail of anticoagulants. It is this welt that is often more annoying than the bite itself. Like all lumps and bumps on the skin, the exact size depends on individual reactions, and individual vanity. It’s not uncommon to hear claims of mosquito bites the size of ping-pong balls or that someone had been bitten so many times their skin looks like bubble wrap.

In the end, it is not the frustration and annoyance at a single bite that vexes most mosquito victims, it is the feeling of persistent, dogged attack from skin-crawling hordes. It was these multiple attacks that first lifted mosquitoes beyond being simply irritating trifles, and raised them to the level of infuriating, noxious pests.