3 Pest Proportions

Whoever came up with the expression ‘the attention span of a gnat’ was definitely not a victim of mosquito-biting. One of the most unnerving aspects of mosquito behaviour is their dogged persistence. Humans live in a world where sight is the dominant sense, and we may assume that we are safer if we stay indoors, keep a low profile or wear sensible clothes. Unfortunately, we smell, and mosquitoes hunt us by the scents we give off.

It has long been known that mosquitoes are attracted to carbon dioxide in our breath. This is a ‘long-distance’ hunting technique, useful over scores or hundreds of metres. The mosquitoes find the source of the carbon dioxide by flying upwind. If they lose the scent, they just drift downwind a bit, or move crosswind, left or right, until they pick up the plume again.

Perhaps the most striking feature of their carbon dioxide detection is that mosquitoes ignore a continuous concentration of the gas, even if it is raised above normal background levels. They are not attracted to continuous emitters like fires or decomposing organic matter. They are, however, highly stimulated by pulses of carbon dioxide – pulses caused, very conveniently, by breathing.

Mosquitoes can also detect ‘odorants’ in our perspiration. The thirteenth-century encyclopaedist Albert von Bollstädt, usually known as Albertus Magnus, was paraphrasing Aristotle when he wrote in his De Animalibus: ‘They have a predilection for men and animals that sweat and therefore they are found much on sleeping persons.’1 Many folk repellents are based on the notion that these odours can be masked; Aristophanes suggested vinegar, hemp, onion and burned shells.2 Unfortunately, mosquitoes are attracted to specific substances, rather than just body odour. These simple chemicals occur in such minute amounts that we are completely unaware of them ourselves. Chief among these seems to be nonanal (nonanaldehyde), a nine-carbon aldehyde that, concentrated in a bottle, smells like fruit or flowers. Combined with carbon dioxide, nonanal sets mosquito antennae aquiver.3 This is their target-acquired signal; the mosquito can, quite literally, smell its next meal, and it won’t give up.

| The mosquito comes to symbolize irritating distraction and painful loss of sleep in a seedy hotel in the Coen Brothers’ black comedy Barton Fink (1991). |  |

Associating mosquitoes with night-time darkness is deep-seated, and is often exploited by writers wanting to juxtapose the calm rest of sleep with something more tense. Although it did not make it into the current edition of Tintin’s adventures, Hergé used such a device in the original black-and-white strips of The Broken Ear, serialized in Le Petit Vingtième from 1935–7. While sleeping, Tintin dreams he is being stalked by a South American native who fires a dart at him using a blowpipe. He awakes to find that he has, instead, been bitten by a mosquito.

An altogether more sinister air is conjured up in the opening credits to the US TV police drama Dexter (2006–present). The title sequence starts with a mosquito on the arm of the series lead, Dexter Morgan, played by Michael C. Hall; it sinks its proboscis into his sleeping flesh, but in a sudden slap, he flattens it into a bloody splat. The sequence continues with him nicking himself shaving, splashing tomato ketchup over his bacon and eggs, and then messily squeezing the dark juice from a blood orange. There are red stains everywhere. This is, of course, significant, because Dexter is an expert on blood splatters (a ‘bloodstain pattern analyst’) with the Miami Police.

| A cartoon mosquito from Bee Movie (2007): cute and cuddly, and hardly pest-like at all. |  |

But not all mosquitoes bite at night. In fact, determining when and where they are active has been one of the main strands of mosquito research for over 100 years. In central Africa, the notorious Coquillettidia fuscopennata starts feeding just after sundown, and bites through the night. At sun-up, the equally infamous Aedes aegypti takes over. There is a similar spectrum of mosquito preferences when it comes to flying height. In the Mamirimiri Forest of Uganda, Anopheles gambiae flies near ground level and is a constant biter of people, but Aedes africanus is most abundant in the branches around 20 m (65 ft) up, and when it can’t get human blood, it feeds on monkeys. Another key behaviour is whether a particular mosquito species seeks out dark crevices as resting places, or whether it is happy to settle under a leaf, or simply on an exposed tree trunk. This roosting behaviour determines whether a mosquito is likely to venture into the dark shelter of huts and houses (and bite the occupants indoors), or primarily remain outside and bite in the open.

Across the 3,500 mosquito species known, the diversity of feeding and breeding times, flying heights, hiding places, geographic localities and resting, roosting and biting behaviours has evolved to coincide with a broad variety of potential host behaviours. It is this ubiquity, across so many climatic, geographical and habitat lines, that has made mosquitoes so successful. In fact, there is always a mosquito around to bite.

The single bite always comes at some inconvenient moment. Right in the middle of a pregnant pause, at the height of dramatic tension, or during lunch. In their quirky post-Morrison song ‘The Mosquito’ (1972), The Doors bleat on about the mosquito’s mealtime attentions, rhyming it with burrito. Not their best work, but indicative of how mosquitoes are always getting in the way. At least in DreamWorks’ Bee Movie (2007) the mosquito gets its comeuppance. After the human protagonist, florist Vanessa (Renée Zellweger), first discovers that hive malcontent Barry B. Benson (Jerry Seinfeld) can talk, they have a series of bizarre ‘dates’. During a restful picnic in the park, they’re sitting back enjoying the moment when a mosquito lands on Vanessa. Without a thought, she slaps it dead. A moment of faux pas anxiety is frozen on her face, before both human and bee crack up laughing.

| Mosquitoes are a pest for only one of these 1890s women; the other presumably used the right soap. |  |

MORE THAN JUST A PINPRICK

The single mosquito bite may be annoying, and that satisfying slap to kill it is at least some recompense, but the malevolence increases dramatically with greater numbers. Each mosquito only takes its 1–5 thousandths of a millilitre of blood, but it does not take many to leave a series of painful reminders of their visitations.

In some places, mosquito attack is not just from a few night-time pesterers. Clouds of insects are so thick they look like smoke, and the sucked victims, human or animal, are driven to wild distraction. At one time, there were fears that heavy mosquito attacks might cause significant blood loss, but this would be virtually impossible unless the unfortunate victim were already on the verge of anaemia.

This is not to say that multiple mosquito attack is not dangerous. There are very credible reports of dogs and cattle being literally bitten to death. In 1600, Portuguese soldier and traveller Pedro Teixeira wrote of his travels in Mexico: ‘Along most of this road [Acapulco to San Juan de Ulua] is a plague of mosquitoes, so terrible and grievous that no defence avails against them; and so they stung my best slave to death for me.’4

There are some brave souls who, in the interests of medical science, have measured mosquito-biting rates in the field using their own bodies. The single exposed forearm of one willing victim in a Canadian swamp was attacked nearly 300 times per minute.5 The researchers extrapolated, calculating 9,000 bites per minute for a ‘totally unprotected’ man. Strange and unlikely though this might be, the calculations continue, and it is reported that, in under two hours, the masochist nudist would have lost half his blood – a likely fatal outcome.

Setting aside, for the time being, diseases spread by mosquitoes, multiple bites can be dangerous, even fatal, but not through blood loss. The painful, swollen lump following a single bite is caused by an allergic reaction to the injected mosquito saliva. The human body is extremely good at recognizing even this pitifully small invasion of alien proteins, and it launches an immune counter-attack. The body’s major defence is to release histamine, a biochemical that causes the local blood vessels to dilate. This increases the flow of blood, with its chemical antibodies and invasion-fighting white blood corpuscles, into the attack zone. It also causes the redness and swelling typical of bites and stings. At the extreme, the immune response to the mosquito’s saliva escalates to the self-destructive overload of anaphylactic shock and the whole body reacts massively, by unnecessary and sometimes fatal mass-release of histamine and other defensive biochemicals. Anaphylactic shock in response to mosquito bites is almost unheard of (it is usually associated with bee and wasp stings). Nevertheless, multiply the mosquito’s pinprick assault by many thousands and it’s not surprising that the body’s immune system goes into hunker-down defence mode. It is likely that those cows, dogs and Teixeira’s best slave died as a result of at least some over-sensitivity to mosquito saliva.

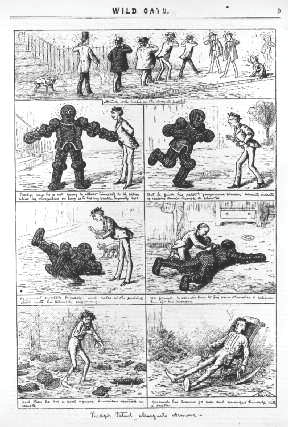

| Frank Bellew’s wood engraving of ‘Protye’s patent mosquito armour’, from Wild Oats (1876); it keeps out the mosquitoes, but lets in other itching insects. |  |

|

In this woodblock print by Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1724–1770), a girl does not leave the safety of the mosquito net whilst trying to restrain her lover from departing. |

SECRETS OF FLIGHT

As we’ve discussed, their persistence in attack, and the painful bites they deliver, have given mosquitoes the reputation for being deliberately troublesome or vengeful. They seek out the hidden sleeper or the relaxing picnicker and are often missed until the deed of blood-letting is done. In the late 1930s, when British aviation company de Havilland was developing a stealthy fighter-bomber, Mosquito was an obvious name for it. It went on to become an icon of British aeronautical prowess, and just one of many examples of the small, bloodsucking fly giving rise to brand names where an edge of danger, annoyance or cool was required.

It is no wonder that such an acrobatic plane should be named after a fly. And it is no coincidence that flies, supreme aeronauts, are named for the very act of flying itself. Despite its flimsy body and unfeasibly long legs, the success of the mosquito as a stealthy bloodsucker is more than partly down to the fact that it has (like other flies) just two wings. Most flying insects have four wings, and there is no doubt that the ancestral insect type had this number, too. But two wings is better, and only the flies (insect order Diptera, di-ptera meaning two-winged) have this number, reduced long ago in evolutionary history so that what were once back wings are now little more than tiny, sensory knobs used in balance and three-dimensional orientation.

Having only a single wing on each side of the body gives flies much greater manoeuvrability, speed and stealth (the same applies to planes, of course.) Indeed, some insects – butterflies, moths, bees and wasps – couple front and back wings together with small hooks, so that the four wings operate as just two aerofoils. Lots of flies utilize their aeronautic ability to perform spectacular manoeuvres: hovering in mid-air, landing upside down on the ceiling, pouncing at top speed and skulking about in the herbage.

It is the gentle landing hover that has given mosquitoes a sneak-attack advantage when it comes to the bloodsucking battle with humans. The gentle touchdown is achieved by a combination of long, impact-absorbing legs and the structure of the wings. The narrow shape of the wings is energy-efficient and the scales, whether forming pretty patterns or an even dusting, help reduce drag. The fringes of long scales on the trailing edge of mosquito wings act like ailerons, reducing turbulence during flapping.

With small, narrow wings comes a high frequency of wing-beats. Most textbooks give 400–600 Hz (beats per second) for mosquito wings; this is towards the high end of insect flapping capability.6In other flying animals, flapping frequency is dictated by the maximum speed at which nerves can generate and fire impulses, then recover again for the next impulse – hummingbirds manage about 90 Hz, for example. For large insects, like dragonflies, wing speeds of this same order are adequate, but these frequencies become much too slow to sustain tiny insects. To get over this, the wings of more ‘advanced’ insects (like flies) are no longer stimulated by direct signals from the central nervous system. Instead, the wings self-stimulate. As the wings flap down, they distort the stiff box of the thorax, tweaking internal sensors that automatically fire internal signals to muscles that pull the wings back up; as they do so, they flex the thorax again and tweak more sensors, which fire signals to other muscles that flap the wings down again. With central nerve transmission now unnecessary, the wing stimulation/firing/flapping/recovery cycle is shortened to the point where wings can flap at over 1000 Hz. Polish entomologist Olavi Sotavalta found that the tiny biting midge, Forcipomyia, could vibrate its wings at 1046 Hz, but he was able to increase this to 2200 Hz by heating up the insect and cutting off most of its wings.7 Perhaps he was exacting a childish vengeance on the bloodsucker during his experiments.

The combination of fast wingbeat and long, narrow wings gives an insect supreme aerial dexterity. It also creates its audible buzz. The high-pitched whine of a mosquito is something that most people will recognize, even without a detailed knowledge of dipteron structure or physiology. But it can be misunderstood. The ancient Greeks supposed that insects produced their buzz by an opening in the abdomen. Aristophanes claimed that ‘the behind of the empides is a trumpet’.8 In the dark silence of the night bed, a mosquito’s whine is audible as the fly descends around the ears to a vulnerable neck, but only a few centimetres away, it is unheard. High-frequency wing movements, giving a high-pitched note, are surprisingly quiet compared to, say, the lower, louder buzz of the bluebottle or even the housefly. This does not stop a bit of exaggeration. US singer-songwriter and rock icon Iggy Pop sang about the mad gyrations of the ‘Loco Mosquito’, but it’s puzzling to know what insect he was singing about. The secret to a mosquito assault is stealth, not the frenzied buzzing this energetic rock song suggests.

Of course, in cartoons, anything goes. Walt Disney’s Camping Out (1934) sets Mickey Mouse and friends against, initially, a lone humming mosquito, then all its friends and family. The high-pitched whine of the inquisitive insect turns to full-throttle internal-combustion roar as it makes its run-up to prang the backside of Mickey’s horse-friend Horace. This short film is loaded with other mosquito gags: the initial mosquito ‘singing’ along to the music; the angry mob taking on the silhouette of one giant mosquito; and mosquitoes’ pointed beaks being disarmed with peas, clothes pegs and clinching hammer blows. It is slightly surprising that the film shows mosquitoes in an almost sympathetic light. This is something that was to change dramatically when Disney produced The Winged Scourge in 1943.

The hum of the mosquito has also been interpreted in other ways. In Mayan culture, mosquitoes were spies, able to discern names and secrets from the blood of their victims, then whisper them in secret. In one traditional West African myth (lovingly retold by Verna Aardema9), the Mosquito lies to Iguana, who puts sticks in his ears so he cannot hear, but then does not notice Python, who gets upset and scares Rabbit, who startles Crow . . . and a trail of distress and confusion spreads through the forest, resulting in Owl refusing to hoot-up the sun in the morning. Lion oversees a tribunal to unravel the blame, and eventually everyone is appeased; Owl summons the sun, but Mosquito hides to avoid punishment. To this day, he goes about whining in people’s ears: ‘Zeee! Is everyone still angry at me?’ Of course, he then gets swatted.

|

Just one of many mosquito-based gags in the Disney short Camping Out (1934). |

Back in the real world, mosquitoes are far quieter than might be supposed. Buzzing loudly to advertise their presence would be an evolutionary dead-end. The stealth works and by it they are very good at getting blood. Mosquitoes need the blood to produce and mature their eggs and, unless they get swatted (or, more likely, eaten by some predator or other), the eggs will be laid a few days later.

Mosquitoes lay their eggs in all sorts of water, from large rivers, lakes, ponds and marshes to small puddles, ruts and flooded tin cans. They do, however, show a marked preference for dark, stagnant, often fetid, pools, ditches, gutters and swamps. This preference has not gone unnoticed.