4 Mosquito Places

The association of mosquitoes (gnats and midges, too) with fens and swamps has been known for millennia. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BCE, describes the marsh country of Egypt, and how the people there avoided being bitten by the conopides, as the sharp-faced gnats of the time were called. The Egyptians slept on raised platforms where the wind prevented the flies from settling, and they threw their fishing nets over their beds when they slept. Columella, in the first century CE, wrote that farmsteads should not be sited near marshes because it produces creatures armed with troublesome stings.1

Aristotle describes how such flies breed in muddy water and he links them to the group of insects that he believes are spontaneously generated from putrefaction, rather than being the progeny of a mating. He describes how the wriggling worms are generated in the mud at the bottom of wells or ponds. His now rather strange narrative suggests that the mud changes from white to black, then red, and that filaments resembling seaweed start to grow, before breaking off into free-floating red worms.2 Giving a modern entomological explanation of these ancient writings is difficult. The word he uses for these worms – ασκαριδες, askarides – he uses elsewhere for internal parasitic worms, and it is related to words meaning both ‘jump’ and ‘palpitate’, which could refer to the skipping motion of mosquito larvae or the undulating bodies of non-biting midge larvae (family Chironomidae). Blood-red worms in aquatic mud are usually the larvae of these chironomid midges. The worms’ redness comes from haemoglobin, the same red, oxygen-carrying chemical found in vertebrate blood. The midge larvae use haemoglobin to store oxygen, and they can release it in times of deficit, allowing them to live in deep-water mud where other animals cannot survive. Some confusion caused by a mix-up between ‘blood’ in the larvae and the blood sucked by adult mosquitoes is, perhaps, not altogether unexpected.

Writing in the thirteenth century, Albertus Magnus was reworking Aristotle when he wrote: ‘Cinifes [another variant of conops] are flying worms with long legs. They pierce the human skin with a small proboscis. They originate in moisture and are frequent near water.’3

Anglers have long known that various gnats emerged from the water, even if they did not ascribe clear scientific names to them. They gave the adults folk names and crafted fishing lures after them – in Scotland, there were blaes and blacks; in Ireland, duckflies. Ruby gnats, olive gnats and black gnats were, if not scientifically understandable, at least descriptive, and may refer to mosquitoes, biting midges and blackflies respectively.4

The general vagueness of slightly different aquatic worms turning into slightly different flying midges continued into the modern era. Just as ‘gnat’ or ‘midge’ was about as accurate as it got when describing the adults, ‘worm’ was about the only description available when it came to the larvae. Distinctions between the different groups of adult flies became ever finer as entomologists sought to classify them, particularly when the nineteenth century brought keen examination under the microscope. At the same time, their different aquatic life histories were being deciphered. Of all the wriggling worms and flying midges to choose, it is perhaps slightly ironic that the mosquito should be the one that was most popularly studied.

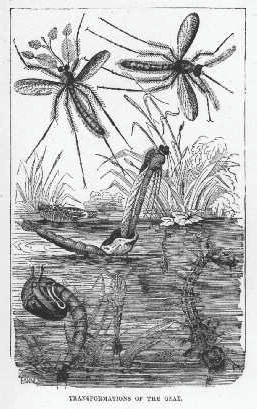

|

The larva of a culicid mosquito hangs down from the water meniscus from its breathing siphon. |

WATERY BEGINNINGS

Mosquito eggs are laid in water, often stuck together in floating rafts, and the larvae live in the water. The ‘wiggler’ larvae are well named for their agile writhing movements. They mainly live at the water surface, taking air through the spiracle (breathing pore) at the tail end, while sieving out microscopic food particles of decaying plant and animal matter at the mouth end. If disturbed, by a passing shadow, they dive down into the murky safety of the deeper water by vigorous flips of their narrow bodies.

Just as adult mosquito types can be identified by their resting body stance, so too can the larvae, by the angle at which they hang down into the water from the surface tension. It’s all to do with how and what they are feeding on. Anopheline species (subfamily Anophelinae) rest parallel to the water surface, hanging here by a ring of water-repellent hairs around the tail-tip breathing pore and other fan-like hairs along the body. They feed by collecting minute particles of decaying organic matter from the surface, and in a strange departure from normal front/back animal anatomy, the larva rests belly-down in the water, but rotates its head 180 degrees so its mouthparts, and the fine brushes of hair it uses to agitate the water, are pointed upwards.

Culicine species (subfamily Culicinae) hang down from the surface at an angle of about 45 degrees, suspended by a long breathing siphon. Aedes larvae swim about nibbling small pieces of algae, or dead leaves; others use their mouth brushes to create eddies to bring floating organic particles into the mouth. These contrasting resting positions are, very neatly, the exact opposite of the striking adult poses (Anophelinae, tail 45-degrees up in the air; Culicinae, body parallel to the surface), and the differences are used to good effect in identification charts.

With the advent of cheap microscopes, cheap printing and the Victorian enthusiasm for nature study, the transformation of the wriggling maggot into the adult fly became one of the standard wonders of nature. It was all the more astonishing because worm-like watery nymph gave rise to faerie airborne imp. Rearing caterpillars through to butterflies may have been more spectacular, but that required at least some knowledge of larval foodplants, and more than a little skill in avoiding the perennial problems of mould and premature escape. Rearing mosquitoes just needed a jam jar full of murky water.

|

Although mosquitoes are derided as the bloodsuckers ‘that murder sleep’, this lovely woodcut from the children’s book Half Hours in the Tiny World (c. 1900) demonstrates the Victorian awe that such wondrous transformations engendered. |

Descriptions and diagrams of mosquito metamorphosis run through all levels of the burgeoning scientific literature of the nineteenth century. At the popular end of the scale, they suited the reverential tone of the ‘juveniles’, the mass-produced illustrated books for ‘younger folks’ printed from the 1880s onwards for increasingly literate middle-class readers. They were usually accompanied by lovely illustrations of the ‘trans formations of the gnat’, showing, especially, the adult fly heaving its delicate body out of the fragile pupal casing. At the more academic end of the spectrum, equally careful and precise illustrations were accompanied by scientific insights into larval body segmentation, respiration, growth patterns, limb formation and hydrophobicity.

Swamp as allegory in a US political cartoon of 1909: if you want to get rid of the mosquitoes (subsidized senators, lobbyists, grafters, kept congressmen, protected monopolies, etc.), you have to drain the swamp (the tariff of politics).

Whether lowbrow or erudite, one fact comes to the fore: mosquitoes breed where there is standing water – marshes, pools, ponds or flooded jam jars. The mosquito is inextricably linked to its watery habitat.

MOSQUITO NEIGHBOURHOODS

Despite the negative connotations, there are plenty of mosquito place names in the world. Google Maps are helpful here. At the parochial end of the spectrum, there are Mosquito Roads in West Malling (Kent), Upwood (Cambridgeshire) and in Georgetown and Placerville (California). There is a Mosquito Way in Hatfield (Hertfordshire) and a Mosquito Lane in Wallingford (Oxfordshire). Quite how mosquito-infested they are is not known. In a slightly less tenuous link to the flies’ swamp habitats, there are also Mosquito Lake Road (Deming, Washing ton), Mosquito Creek Road (Clark Ford, Idaho) and Mosquito Brook Road (Hayward, Wisconsin). Not surprisingly, there is no grandly named Mosquito Boulevard or Mosquito Avenue in any major metropolis in the world.

Some mosquito names are, without doubt, down to the exhausted vexation of early cartographers and explorers, struggling through buggy swamps and across midge-blown moors. The Mosquito Range forms part of the Rockies in Central Colorado. There are Mosquito Harbours (Maine, Vancouver, Ontario), Mosquito Island (British Virgin Islands), and plenty of Mosquito Creeks (Alberta, Vancouver, California, Ohio, Victoria in Australia). All of these are obvious dank mosquito habitats.

Contrary to some people’s expectations that mosquitoes mainly inhabit tropical climes, it is the open, cool wastes of moor, muskeg, morass and mire which often host the greatest numbers of these biting flies. In the highly biodiverse tropical rainforests, there are so many other animals to eat mosquitoes, and so many vertebrate victims for mosquitoes to bite, that their numbers (and their attentions) are reduced. But in the fertile mosquito-breeding grounds of the northern wetlands, there are miles and miles of open, watery swamp populated by relatively low numbers of native birds and animals. As well as hunting after carbon dioxide and nonanal, biting flies are also attracted by dark silhouettes, standing out readily against the flat, featureless landscape.5 The upright human is soon spotted, and soon bitten. Canada, with its vast, labyrinthine mosaic of lakes, rivers and marshes (making up a quarter of the world’s wetlands) makes a good claim to be the most mosquito-ridden country in the world.

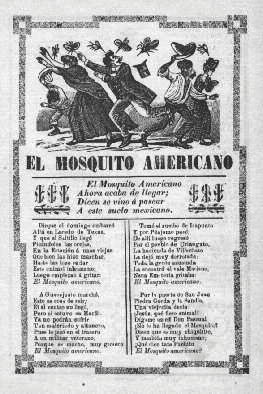

| The Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada wrote El Mosquito Americano in 1903, using the fly as a metaphor for American tourists derided as pests, and for political, industrial and technical advisors, who bring nothing but pain and corruption. |  |

There is something of a love–hate relationship between Canadians and their home-grown mosquitoes, and there is a certain rivalry between towns self-proclaiming to be mosquito capitals. Winnipeg, low-lying on the Red River Valley, makes a claim, and the mosquito is jokingly said to be the provincial bird of Manitoba. Komarno, a small town about 70 km (45 m) north of Winnipeg, is claimed to be named by Eastern European immigrants from the Ukrainian word for mosquito.

The Canadian folk-rock duo Kate and Anna McGarrigle use the mosquito as a symbol of futility in their 1976 ‘Complainte pour Ste Catherine’. The lament for Saint Catherine (the name of a major Montreal shopping thoroughfare and also the patron saint of single girls) likens the long-time struggle of a street hooker to twenty years of war against mosquitoes. This is a poignant reference to the clouds that descend on the marshy Quebec outlands every year.

|

The Lomen Brothers made their name photographing early 20th century Alaska but took time out to celebrate their local mosquitoes. |

| Komarno, Canada, claims to be the mosquito capital of the world, and commissioned a huge statue to promote the idea. |  |

Indeed, Canada holds the rare distinction of being the only country in the world to offer a postage stamp celebrating a place called Mosquito. The small brown Newfoundland eight-cent stamp from 1910 shows a ‘View of Mosquito’. This small town was so named in 1610, the same year that nearby Cupids became the first English settlement in Canada, and only the second in North America. The naturalist and writer Philip Gosse was plagued by mosquitoes during his residence in Newfoundland in the 1830s. Everyone was covered with ‘large white tumours attended with intolerable itching’. He was kept awake by the children crying out at night, and every day the walls of the house were covered with bloated mosquitoes, ‘their abdomens distended and almost bursting with the blood they have extracted from our veins at their leisure’.6

|

The bistre (wood pigment) 8-cent stamp from Newfoundland commemorating the town of Mosquito, later renamed Bristol’s Hope, issued in 1910. |

By 1910, the Newfoundlanders decided it was time to change their historic settlement’s name to something more aspirational. Just as the stamp was published to celebrate 300 years of Newfoundland history, the town was renamed Bristol’s Hope. But there is still a Mosquito Pond behind Beach Road there, and it is unlikely that any mosquitoes took much notice of this over-late public relations exercise.

THE EXPLORER’S BANE

Exactly how or why Newfoundland’s settlement got its name is not precisely known, but during this era of European expansion, mosquitoes featured regularly in the travelogues written by explorers. When Captain Cook, accompanied by naturalists Banks and Solander, first landed in New South Wales on 29 May 1770, they were greatly hindered by swathes of prickly spinifex grass and ‘mosquitos [sic] that were likewise innumerable . . . made walking almost intolerable’.7 In April 1812 eccentric naturalist and traveller Charles Waterton left the town of Stabroek to travel into the wilds of Dutch Guiana, only to find that during the day the sun would exhaust him, and at night ‘mosquitoes would deprive him of every hour of sleep’.8

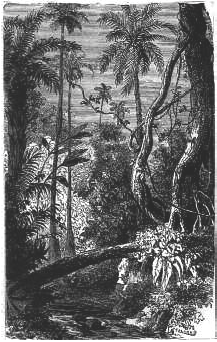

The assault of humans squelching through mosquito-infested swamps makes grim reading, and it would be easy to fill countless pages with references to swampland sufferings. But a potent focus can be brought to bear on the writings of just one particular man. Throughout his long life (1823–1913), explorer, scientist and writer Alfred Russel Wallace spent much of his time and energy considering the persecutions of these tiny, biting insects. In his many books, there is a constant commentary on how and where mosquitoes were biting. In his first major publication (A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, 1853), he comments, for example, that in Para ‘Mosquitoes, in the low parts of the city and on shipboard, are very annoying, but on the higher grounds and in the suburbs there are none.’9

Not surprisingly, since he was travelling by boat through this pristine, watery wilderness, mosquitoes were always with him. As he travels into the interior of South America, he frequently complains that they ‘would not allow us to sleep for some hours’, ‘annoyed us much in the evenings’ and ‘were a great torture’. On several occasions he comments, with barely hidden glee, when the mosquitoes let up for a moment. When he finally gets onto the Rio Negro, he notes: ‘A great luxury of this river is the absence of mosquitoes.’10 Lack of mosquitoes may be due to the river’s water quality. It gets its name from its clear, dark appearance (contrasting with the pale, silty Amazon), caused by tannins leeching out of decaying vegetation creating transparent, tea-like water, with higher than normal acidity.

Needless to say, along other Amazonian waterways, he was pestered endlessly:

the mosquitoes here were very annoying . . . we found them unbearable . . . they soon found their way in at the cracks and keyholes, and made us very restless and uncomfortable all the rest of the night . . . We found them more tormenting than ever, rendering it quite impossible for us to sit down to read or write after sunset.11

He tried everything to keep them at bay:

The people here all use cow-dung burnt at their doors to keep away the ‘praga’ or plague, as they very truly call them, it being the only thing that has any effect. Having got an Indian to cook for us, we every afternoon sent him to gather a basket of this necessary article, and just before sunset we lighted an old earthen pan full of it at our bedroom door on the verandah.

Luckily, the cow dung ‘gives a rather agreeable odour’.12

Despite his regular protestations, Wallace was no pathetic whinger; he was a hardened, independent traveller risking his life among wild animals, indigenous people and all the dangers of travel in the jungle and under sail. On 6 August 1852 he was returning across the Atlantic – a few days out from Para, on the ship Helen – when fire was discovered deep in the hold. Despite the crew knocking holes in the cabin floors and pouring in water, the fire spread and the whole ship was eventually engulfed. Wallace had time to grab a few notebooks and a couple of shirts before he and the entire crew had to abandon the vessel. They spent ten days in open lifeboats, until they were picked up by a passing cargo brig bound for London. Wallace, the undaunted Indiana Jones of his day, rested up in England a year, planning his next venture, and was soon off again: to the Malay Archipelago in Southeast Asia.

This time, he made full and good use of a bed net to try and get some release from his aggressors. In Aru, an island south of New Guinea, he turned in under his mosquito curtain ‘to sleep with a sense of perfect security’. Mind you, ‘in the plantations, where my daily walks led me, the day-biting mosquitoes swarmed, and seemed especially to delight in attacking my poor feet’.13 Wallace was a self-financing traveller, supplying specimens (mostly birds, butterflies and beetles) to wealthy patrons back home. He needed the evenings to prepare specimens, write up his notes and correspond with his colleagues back in Britain. His mosquito net was his only solace. At one point in his records of the trip we find Wallace outraged by the lean and hungry dogs that prowled the nights below his stilted house. They had previously destroyed several valuable bird of paradise skins ‘incautiously left on my table for the night’, but he saves the peak of his ire for recalling those in a Dyak’s house in Borneo: ‘they gnawed off the tops of my waterproof boots, ate a large piece out of an old leather game bag, besides devouring a portion of my mosquito-curtain!’14 His exclamation mark, by the way.

Wallace also suffered from ague, a recurrent fever, which frequently wracked him during his travels. He did not, at the time, know of its link to the very same mosquitoes that so vexed him. References to ague punctuate his writings: ‘One of my best Indians fell ill of fever and ague . . . On leaving Sao Gabriel I was again attacked with fever, and on arriving at Sao Joaquim I was completely laid up.’15 And: ‘I had a slight attack of fever, and almost thought that I was still doomed to be cut off by the dread disease which had sent my brother and so many of my countrymen to graves upon a foreign shore.’16

Portrait of Alfred Russel Wallace, 1862.

‘Stream through the Forest’ from Alfred Russel Wallace, Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro (1853).

It was during one of these incapacitating attacks – in early 1858 at Ternate, in the Maluku Islands, ‘shivering under the cold fit of ague’ – that he found time to mull over ideas about the struggle for survival in nature.17 As soon as the fever passed, he sent his famous essay to Charles Darwin, independently suggesting the idea of evolution by natural selection, and prompting Darwin to publish their world-moving joint papers at a meeting of the Linnean Society in London in July later that year.18 Wallace did not appreciate it at the time, but the single most important concept in biological science was triggered years before by a bite from one of those irritating mosquitoes somewhere in the Amazon jungles.

Wallace used the traditional English term for this ailment, ague, but very soon a more sinister word would come into fashion. Along with the biting mosquitoes that they bred, swamps and quagmires often give off the fetid and indelicate smell of decay – methane (natural gas) and hydrogen sulphide (like rotten eggs) were by-products of the bacterial breakdown of dead leaves and other organic material in the oozy muds. Near towns and cities, marshes were wet with slow-moving water, which did not flush away sewage quite as quickly as the inhabitants might have wished. Diseases like ague became linked to the foul breath of the wind off these polluted mudflats. Victims were thought to have fallen to the dangerous miasmas wafting in from the estuaries, the bad airs, the mal’aria.