8 Environmental Chaos

DDT was the wonder chemical of the twentieth century. Wherever it was used, there were astounding results. In January 1946, Italian malariologist Alberto Missiroli astonished his audience at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Department of Health) when he proposed to stop all the previous measures to counter malaria – spraying breeding sites with larvicide, use of screens and bed nets, quinine prophylaxis and land reclamation. Instead, he suggested, they should just spray DDT in buildings. In 1949 and 1950, for the first time in over 2,000 years, there was not a single death from malaria in Italy, Sicily or Sardinia.1

Unfortunately, not everything was going as well as the manufacturers might have wished. There were some concerns about DDT’s toxicity to fish, and there were anecdotal reports of domestic cat illness and deaths. The commercial importance of DDT made the quiet worries and complaints easy for the powerful manufacturers to ignore, and things went ignored for a long time; but in the end, all it took was a letter from an old friend.

In January 1958 Olga Owens Huckins wrote to her friend Rachel Carson, enclosing a copy of a letter she had just written to the Boston Herald, complaining of bird deaths after local DDT spraying against mosquitoes. Carson, a former biologist with the US Bureau of Fisheries, and by now a successful science writer, took up this report, and started to delve into similar events. In 1962 she published Silent Spring. The book opens with a Lovecraftian evocation of sinister change in an idyllic rural landscape. She begins:

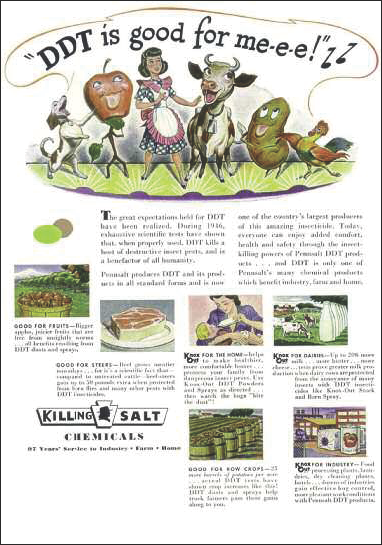

During the 1940s the insecticide DDT was actively promoted as being good and healthy.

a checkerboard of prosperous farms, with fields of grain and hillsides of orchards . . . foxes barked in the hills and deer silently crossed the fields . . . along the roads, laurel, viburnum and alder, great ferns and wildflowers delighted the traveler’s eye . . . The countryside was, in fact, famous for the abundance and variety of its bird life.

But:

Then a strange blight crept over the area . . . mysterious maladies swept over the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was the shadow of death. The farmers spoke of much illness among their families . . . There was a strange stillness. The birds, for example – where had they gone? It was a spring without voices . . . only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.2

Carson’s opening chapter is eerily similar to H. P. Lovecraft’s short story, ‘The Colour Out of Space’ (1927). In a similar New England backwater, the story’s narrator discovers a plot of land strangely devoid of life. The plants and animals become grey and brittle, and exhibit a slight phosphorescence. The farmer and his family are struck by illness and insanity. In this case, the cause of this otherworldly blight is a meteorite that had crashed into the well. We never quite discover what alien chemical (or being, perhaps) is in the well, but the rising sense of dread, as the poison spreads and clues emerge, has eerie parallels to Carson’s unfolding investigation.

The underlying fugue of Carson’s groundbreaking book was the devastating effect of indiscriminate use of highly toxic poisons across the environment. DDT was a name on everyone’s lips. Insecticides were sprayed with such cavalier abandon that whole neighbourhoods were poisoned, and it was non-target organisms that suffered. Chemicals were washed away in the water run-off and entered the rivers, killing fish and polluting drinking water. In 1959, pellets of Aldrin (an organochloride similar to DDT) were scattered so thickly against Japanese beetle in the Detroit suburbs that the ground was blanketed like snow. This killed the beetles, a notorious invasive alien pest, but also their predators and parasites. The toxin was absorbed by earthworms, and by the birds that ate them. The very chemical property that gave the synthetics their value – their long biological life – meant they were not broken down by the birds’ metabolism; instead they were accumulated in the body fat, a substance biochemically very similar to the liquid oils in which DDT was sprayed. DDT caused shell-thinning in birds’ eggs, which were quite literally crushed underfoot in the nests.3 It was the demise of the birds that triggered Huckins to write, and it was the silence of the birds departed that gave Carson’s book its title and chilling message.

The appearance of Silent Spring is widely regarded as the signal event that started the modern environmental movement.4 It was serialized in the New Yorker, and soon made its way into the New York Times bestseller list. The book and its accusations were discussed by national governments, the international media and the general public. Those chemical pesticides, once lauded as scientific miracles, were now damned as environmental pollutants. DDT was banned in Hungary in 1968, Sweden in 1970, Germany and the USA in 1972 and, eventually, in Britain in 1984.

MUTANT MOSQUITOES

Back in the 1950s and ’60s, environmental poisoning was only one of the rising biological issues sparked by indiscriminate DDT use. Mosquito resistance to DDT had started to appear as early as 1956.5 Likened to evolution in action, inconsistent DDT use meant that some mosquitoes, with chance mutations in the DNA responsible for the nerves it normally poisoned, were immune (or at least resistant) to the chemical. They survived and passed on this mutated gene to their offspring. Soon hardier generations had replaced the susceptible insects and new, resistant populations were no longer affected by DDT. Perhaps not surprisingly, the first species to show this resistance was one of the key malaria vectors in Africa, Anopheles gambiae, and one of the first fears was that insecticide spraying would cease to have any control over the disease in the area.

At this same time, vague, dystopian, science-fiction notions of radioactivity, genetic mutation and alien invaders were mixed into an anxiety of general biological upheaval. Hollywood, ever keen, but not the best measure of scientific understanding, now launched a series of outlandish giant insect horror movies. This was the time of Them! (1954), often cited as the worst film ever made, in which giant mutated ants the size of automobiles maraud through New Mexico. In The Deadly Mantis (1957), a volcano dislodges a 60-m (200-ft) praying mantis locked in Arctic ice for millions of years. In Monster from Green Hell (also 1957), wasps sent into space in a test rocket return and crash-land in Africa, where they transmogrify into green giants.

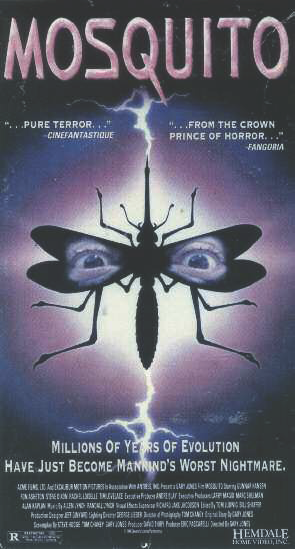

Everything got mixed up in these now dated vignettes. Despite the importance of mosquitoes, we had to wait until 1993 for Skeeter and 1995 for Mosquito. Both feature giant, mutated bloodsuckers, the first arising from dumped toxic waste, the other from feeding on decaying aliens killed in a flying saucer crash. Although 40 years too late, the films do not disappoint in their clichéd, B-movie horror styles, with rampaging giant insects, explosions and a lot of people screaming.

The word ‘overkill’ comes to mind now when we think about the tons of toxic chemical strewn over the landscape to kill mosquitoes. When the Monty Python team set about their Mosquito Hunt (1970), it was overkill that made the whole sketch funny. As they mock entomologists, game hunters and Australians (‘I love animals, that’s why I like to kill ‘em’), they set off to stalk the insect with bazooka, machine guns and high explosives. The ground smokes as they finish the insect off (‘There’s nothing more dangerous than a wounded mosquito’), but the bombs and bullets they dispatch are relatively harmless compared to the almost unimaginable volume of chemical insecticides used in the real world.

It is funny, now, because we have forgotten the burden of ague and the nightly irritation of persistent biting attack. Malaria went from the USA by the 1950s and the National Malaria Society was officially disbanded in 1952. The last recorded case in Britain was about the same time. In the space of 25 years, one generation, killing mosquitoes went from being an unpleasant necessity to a joke. Another generation on, and memories of mosquito dangers are lost still further; we become ever more urbanized, and windows stay shut as houses benefit from double glazing, central heating and air-conditioning.

The earth-shaking discoveries of the 1890s, and the epiphany of understanding when the mosquito–disease knot was unravelled, fell upon a society ripe for the knowledge. It all coincided with similar discoveries about the spread of microbes by houseflies, and revolutions in sewage disposal and piped water delivery. But the novelty has faded. To some extent, those great mosquito discoveries were only the beginning; research continues today. New diseases and new vectors are being found, but details become ever more focused and refined, and the minutiae of mosquito life become ever more abstruse. The current wave of mosquito research is erudite in the extreme, but the papers published in arcane journals are usually well beyond the scope of the general reader or educated layman. DNA analysis of individual mosquito genes, scanning electron micrographs of obscure body parts, molecular analyses of blood-digesting enzymes, isotopic labelling of physiological pathways and genome mapping of Plasmodium falciparum all add to the corpus of accruing facts, but with an increasingly technical scientific jargon and complex mathematics, they are outside the understanding of the general public and are generally ignored by the press.

Mosquito was a 1950s-style horror B-movie, made in the 1990s. The giant mosquitoes were anatomically correct on screen, but the video cover is pleasingly daft, showing an insect with the wrong number of wings.

This has led to the strange situation that, although scientists learn more and more about mosquitoes and their diseases, the general public (including the policy- and decision-makers of government) learns less and less. General ‘knowledge’ of how and why mosquitoes spread disease is being watered down and replaced by caricature and myth. For many people, mosquito knowledge is slowly becoming a mosquito stereotype. This is not helped by the increasing emergence of the mosquito brand.