Children’s responses to the portrayal of wolves in picturebooks

Kerenza Ghosh

The wolf has existed alongside humans for centuries, both in reality and through literary and cultural representations. Consequently, the mere mention of the word ‘wolf’ evokes an immediate response within most people. Stereotypical images of this creature are embodied in traditional stories which have been passed on from one generation to the next. More recently, polysemic picturebooks offer renewed portrayals of the wolf, which challenge and

extend the reader’s expectations of this character within stories. Such books employ metafictive devices to recast the wolf, encouraging readers to adopt an active approach when interpreting these texts. Beginning with a history of the wolf in literature, this chapter considers how the

portrayal of wolves in contemporary picturebooks is often unconventional and thought-provoking. It then goes on to analyse the responses of a group of children, aged 10 and 11, as they read and discussed two polysemic picturebooks featuring the wolf. The children’s discussions around these idiosyncratic texts built upon their previous experience of this

animal in folktales, fables and in reality. The overall findings demonstrate how such picturebooks provide rich opportunities for the development of reader response, in relation to diverse, sometimes frightening, and often challenging, representations of the wolf.

Why the wolf?

The truth is we know little about the wolf. What we know a great deal more about is what we imagine the wolf to be (Lopez, 1978: 3).

The influence of culture and imagination over our impressions of the wolf is acknowledged by Lopez’s statement. This animal has come to be part of our ‘collective unconscious’ (Jung, 2010: 42), an archetype developed subliminally by society, transcending time and tradition. Throughout their existence, wolves have endured varied treatment from humans. Twentieth-century observations of actual wolves in their natural habitats show them to be exceptionally social and elusive animals, who rarely pose a threat to people (Lopez, 1978). Comparisons have been drawn between the evolution of wolf and man, as both species developed the intelligence to outwit their prey and used their social tendencies to cooperate as a group during the hunt and when caring for their young. Generations of Native Americans have respected the wolf as a lodestar in their tangible and spiritual worlds. However, during the 1600s, American settlers who depended upon domesticated animals for food and work found that wolves were turning to livestock for their food source. Together with this real threat to farmers’ livelihoods, religious community leaders exploited images of the wolf within the Old Testament. Jesus’ followers were sent out into the world ‘as lambs among wolves’, and were warned to stay alert to people who may be morally corrupt. Thereby, the Biblical wolf became symbolic of any human threat to the spiritual lives of early Christians. This methodical demonisation of the wolf led to ‘lupophobia’, not merely fear, but deep hatred towards this creature (Marvin, 2012). Consequently, throughout Europe and America from the Middle Ages onward, wolves have been persecuted by humans and hunted to near-extinction. Only in the 1970s did the wolf become listed as an endangered species in America, after an alarming census reported their dwindling numbers. There has since been a resurgence of wolves in the wild, across North America, Canada and Europe, news which continues to generate debate between conservationists, governments and farmers alike, identifying the wolf as a subject of extreme controversy.

Within the English language, common idioms allude to what is often perceived as the behaviour of real wolves: ‘lone wolf’, ‘wolf it down’, ‘to cry “wolf”’ and ‘keep the wolf from the door’ suggest isolation, greed and deception, and invoke protection against evil omens (Brewer, 1995). Through the years, adverse opinions of this animal have even extended to the popular playground game, ‘What’s the time, Mr Wolf?’, whereby children are beckoned gradually towards the ‘wolf’, who suddenly shouts ‘Dinner Time!’ before chasing the others to catch them. Musically, the wolf has been portrayed as an imposing figure: in Peter and the Wolf, composed by Sergei Prokofiev (1936), three French horns perform a grand, ominous refrain to signify his presence. This particular rendition of the wolf has been further developed through stop-motion animation (Templeton & Prokofiev, 2006). However, instead of being captured and taken to the zoo as in Prokofiev’s original story, in this animated version Peter shares an affinity for freedom with the wolf, allowing him to escape back into the forest. Alongside this, television documentaries such as David Attenborough’s Frozen Planet (2011) have given insight to the struggles faced by wild wolves, their intrinsic role in the ecosystem, and the curious, friendly nature of a lone wolf. Peter Hollindale (1999) argues that humankind’s relations with the wolf are more complex and intimate than with any other wild creature, making the wolf a robust subject for storytelling. A myriad of stories, from traditional tales to contemporary picturebooks, have contributed in various ways to the wolf’s literary image.

A history of the wolf in children’s literature

The fables of Aesop, originating around 600

BC, are some of the oldest tales known to associate the wolf with specific character traits. Distinguished by size, hunger and gluttony, the fable-wolf is typically dishonest and cruel. His insatiable appetite reflects danger, and is the source of his actions and the reason for his existence (Mitts-Smith, 2010). Morals reinforce this stereotype: The Wolf and the Crane deems him ‘wicked’; The Wolf and the Shepherd announces the damning indictment, ‘once a wolf, always a wolf’ (Aesop, 1919). Contrary to popular belief, this animal is not always successful in his ravenous endeavours: The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing proclaims him an ‘evil doer’, yet his tactic to masquerade as a sheep backfires, resulting in his downfall. In The Wolf and the Kid, the wolf falls victim to trickery, duped into playing music, then chased by dogs as the kid escapes. The Wolf and the House Dog sees him undernourished and dejected, although he does symbolise liberty compared to his cousin, the dog, who is suppressed through domestication. Such lesser-known Aesopian tales can challenge the expectations of the reader who is used to hearing fables of pure wolfish greed and menace.

Folktales likewise tend to represent the wolf in a negative way. Perhaps the most well-known is Little Red Riding Hood, said to have originated in Europe during the Middle Ages, a time when wolves were the predominant predator living in close proximity to human beings. This historical period saw much social and political unrest: extreme poverty and hunger meant that violence amongst people was rife, and children were believed to be under constant threat from sinister men, wild animals and the hybrid figure of the werewolf (Zipes, 1993). Widespread superstition and anxiety framed the wolf as a scapegoat for social misfortune, and Little Red Riding Hood was told as a cautionary tale to warn about the dangers of life. The classic version by Perrault (1697) tells of a young girl lured into bed by the wolf, wherein he attempts to attack her. Clearly, the desire is sexual as much as nutritional, turning the wolf into a symbol for lustful, seductive men. The Grimms’ (1812) retelling, which does not feature the pair in bed together, is widely shared today and continues to inspire contemporary illustrators such as Daniel Egnéus (2011), who uses gothic imagery to encapsulate its horror and romance. For Jack Zipes, the reason for this story’s enduring popularity is clear: ‘it is because rape and violence are at the core of the history of Little Red Riding Hood that it is the most widespread and notorious fairy tale’ (1993: xi). It stands out as having been reimagined for readers of all ages in virtually every genre and mode imaginable. Sandra Beckett, in her extensive work on Little Red Riding Hood, presents a collection of translated versions, showing how,

various threads of the traditional tale have been woven together differently to reflect changing times, audiences, aesthetics and cultural landscapes. The number and diversity of these retellings from the four corners of the globe demonstrate the tale’s remarkable versatility and its unique status in the collective unconscious and in literary culture, even beyond the confines of the Western world.

Beckett (2014: 11)

These works recast this story, from traditional perspectives, to playful versions and innovative approaches focusing on the wolf or wolf-hood.

Myth and legend from other countries have also laid claim to the wolf. In Norse mythology, wolves threaten the Gods, time and life itself. Chariots bearing the sun and moon are pursued by two wolves, setting time in motion and forcing it to move at a vigorous pace. Catching up with their prey will bring about the release of Fenrir, a monstrous wolf whose destiny is to initiate the end of the world. Medieval legends of St Francis of Assisi tell of a frighteningly large wolf which devours livestock and people. In these tales, the wolf’s predatory instinct and choice of victims defines his behaviour as fearsome and his character as immoral. Contemporary retelling, Brother Wolf of Gubbio (Santangelo, 2000), emphasises the plight of the lone wolf, starving, tired and too old to travel with his pack. He is eventually tamed by the kind treatment of St Francis, who accepts that natural hunger drove this creature to hunt animals; therefore the wolf is without sin. Compared with the original legend, this presents a more ecological depiction of the wolf as a predator (Mitts-Smith, 2010). One tale which holds the wolf in highest regard is Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, who as babies were protected and nursed by a she-wolf. Since the wolf is so often taken for granted to be male, this female depiction is notable and rare. Naturally, the story of Romulus and Remus, believed to have originated around 750

BC, influenced the attitudes of Romans, who viewed wolves favourably. For them the wolf pack embodied characteristics valued in ancient Roman civilisation and military life, including group loyalties and intuitive tactical understanding. Over time and across different cultures, the wolf has recurred as an archetype, creating ‘myths, religions and philosophies that influence and characterise whole nations and epochs of history’ (Jung, 1978: 68). These ideologies continue to be shared today, through storytelling and adaptations of original tales, demonstrating their continued significance within society.

Deconstructing the wolf in children’s literature

Naturalistic depictions of pack animals are found in The Jungle Book (Kipling, 1894). In this classic novel, the wolves who are Mowgli’s brothers behave similarly to wolf cubs in the wild, offering him loyalty and companionship. Despite these positive portrayals, Hourihan states that ‘the effect of the folkloric and literary tradition on living wolves has been catastrophic’, and calls for this convention to be deconstructed (1997: 126). Following The Jungle Book, other contemporary novels have offered complementary images of the wolf: Wolf Brother (Paver, 2004), for example, is the first in a series of books about the bond of friendship and loyalty between a boy and a wolf. However, within literature this animal continues to be conceptualised in diverse and challenging ways. At one extreme the wolf is a male stereotype, deemed to be a purely frightening, hostile force, yet elsewhere the wolf can be naïve, dim-witted, sensitive and even benign. This suggests that the wolf is a social and literary construct, depicted according to whatever may be the intended purpose. Such varied representations indicate that the wolf can act as a metaphor to show that not all human behaviour is wholesome or harmless, but also that humans should develop a sense of empathy for others. The following section explores a range of contemporary picturebooks and considers wolf characters that are stereotypical, parodied, undone, temperamental and reformed, along with female representations of the wolf.

The wolf in contemporary picturebooks

Time and again, wolves have been used allegorically to represent fear, threat and danger. TheWolf (Barbalet & Tanner, 1992) is a metaphorical tale about confronting and mastering one’s own terrors. The story tells of three children and their mother, whose tranquil life is shattered when a wolf begins to howl forebodingly outside their house. The family members become virtual prisoners, barricading themselves inside their home in an attempt to ward off the beast. Alarmingly, one child wonders whether he should sacrifice his cat, or even himself, to appease the creature. The family gradually realise they must face their fears, and gather the courage to unbar the door and admit the wolf. The fact that the wolf never actually appears in the illustrations intensifies its power as a metaphor, and its influence is evident in the dramatic, realistic portraiture of the characters. A far sinister incarnation of the wolf is found in The Girl in Red (Innocenti & Frisch, 2012), wherein this creature manifests itself as a young man, heroic and handsome, yet morally suspicious: ‘A smiling hunter. What big teeth he has. Dark and strong and perfect in his timing’ (2012: unpaginated). Language and image both draw deliberate comparisons with the folktale wolf, and events later on in the story imply that this man has committed extreme violence against Sophia and her grandmother. The general ambiguity around the characters and plot raises challenging questions about safety and risk, to ensure that this recasting of Little Red Riding Hood retains the same impact as the original cautionary tale.

First person narrative can be used to parody the wolf in folktales. The Wolf’sStory (Forward & Cohen, 2005) and The True Story of the Three Little Pigs (Scieszka & Smith, 1991) are each told from the viewpoint of the wolf, presenting him as the ill-fated hero, rather than the villain. Response is encouraged as each narrator addresses the readers directly, imploring them to listen to his side of the story: The Wolf’s Story begins, ‘No, please. Look at me. Would I lie to you?’ (Forward & Cohen, 2005: unpaginated). The turns of phrase he uses have double-meanings, implying that his intentions are not wholly honourable: in trying to proclaim his innocence and work ethic, the wolf’s pun, ‘I won’t make a meal of it!’, undermines his self-image. The True Story of the Three Little Pigs also opens informally: ‘You can call me Al. I don’t know how this whole Big Bad Wolf thing got started, but it’s all wrong’ (Scieszka & Smith, 1991: unpaginated). Illustrations of rabbit ears stuffed in burgers are juxtaposed with Al’s innocent tone. Reading on, it becomes evident in his use of rhetoric, and through certain unneighbourly behaviour, that Al’s version of events may not be entirely truthful. In both of these stories, the combination of a satirical narrator and manipulation of visual viewpoint means that the reader must actively decide whether or not to trust these beguiling wolf-narrators.

In certain stories, the wolf can be undone by those who traditionally fall victim to him. In Little Red Hood (Leray, 2010), a fearless young girl is wise to the wolf’s gastronomic motives. She skilfully diverts her accoster’s attention as he tries to engage her in the familiar exchange about big ears, eyes and teeth. Boldly, she questions the wolf’s personal hygiene, offering him a poisoned sweet to freshen his breath. Upon eating this, the wolf dies dramatically, and with cynicism Red denounces him a ‘fool!’ (Leray, 2010: unpaginated). The witty reversal of traditional roles gives Red the upper hand, conveying an acute sense of power. This subversion harks back to The Story of Grandmother, an oral French tale told during the late Middle Ages, in which a clever girl held hostage by a werewolf tricks her captor into letting her go outside to use the toilet (Zipes, 1993). Once out of sight, she is able to make her getaway, thereby foiling the monster’s plan and undermining his deceitful persona.

Bruno Bettelheim declares that ‘we all refer on occasion to the animal within us, as a simile for our propensity for acting violently or irresponsibly to attain our goals’ (1975: 175–176). Bettelheim argues that the metaphoric temperamental wolf, ensconced in the child characters of certain stories, can offer valuable lessons about willpower, since it represents subconscious, disruptive forces. One must learn to conquer such forces though strength of character, as seen in Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963). Dressed in a wolf costume, Max makes mischief. He is banished to his bedroom and in retaliation sails away to the land of the Wild Things. Max’s temper, his inner wolf, is signified by the creatures that live there; once he has gained control over them he is ready to return home. The act of taming an upset mood is also explored in Virginia Wolf (Maclear & Aresnault, 2012). Awaking one morning in a rage, Virginia, a young girl, skulks around the house, growling and howling, her silhouette revealing lupine ears, teeth and tail. Thanks to her sister’s artistic efforts, Virginia’s anger gradually fades, her wolf ears become a decorative hair bow and harmony is restored. Taking inspiration from the life of modernist writer Virginia Woolf, who suffered with depression, the story sensitively addresses the complexities of melancholia. In both picturebooks, transformation from wolfish to serene enhances the drama and its resolution. Such characterisation of the wolf may introduce children to the intricacies of human behaviour and emotion, enabling them to manage their own actions and deal with the conduct of others.

Some stories see the wolf himself reformed. On the way, he often suffers humiliation rather than harm: upon drinking large quantities of ginger beer in Little Red: A Fizzingly Good Yarn, the wolf lets out ‘an enormous burp’ causing Grandma to fly out of his mouth (Roberts & Roberts, 2005: unpaginated). In return for promising not to eat anyone else, Little Red provides the wolf with a continuous supply of ginger beer, which he quaffs eagerly despite its embarrassing after-effects. Though he remains a glutton, this newly vegetarian wolf is a comedy figure and far less threatening. Alongside improvements to dietary habits, becoming literate is another route to rehabilitation, as seen in A Cultivated Wolf (Bloom & Biet, 2001). The farmyard animals, whose peace and quiet is disturbed by lupine howling, will not tolerate such aggressive, antisocial behaviour. To be accepted, the wolf must prove himself a good influence on those around him. This he accomplishes by learning how to read. His positive transformation is confirmed in the final endpapers, which show him reading happily to a group of children: he is now a fully integrated, cultivated member of society. Reformed wolves carry ‘human attributes and values, creating characters which share our concerns and behaviours. In this way, the wolves of children’s books mirror and model the lives of their audience’ (Mitts-Smith, 2010: 3), demonstrating contemporary values and exploring the challenges that arise from social relationships.

The imposing masculine figure of the Big Bad Wolf, with his wily ways and voracious appetite, appears to have damaged the reputation of Canis lupus. Through consideration of gender, modern reversions of Little Red Riding Hood can offer more positive representations. Little Evie in the Wild Wood (Morris & Hyde, 2013) is one such retelling. References to the classic tale are clear: the wild wood signifies danger, and Evie stands in a vivid red dress against the dark, silhouetted wolf. Familiar descriptions of the wolf emphasise Evie’s vulnerability: ‘Great eyes, the better to see her with. Great ears, the better to hear her call. Sharp teeth like daggers’ (Morris & Hyde, 2013: unpaginated). The similarity ends here, as the traditionally male beast is reimagined as female, and Evie presents her with a basket of jam tarts, baked by Grandma as a gift. Poetic images reflect the benevolence of this she-wolf: her velvet ears and warm body are a comfort in the chill of the night, and she returns Evie safely home to her mama. Themes of domesticity and nurture evoke those maternal instincts of the mother wolf in Romulus and Remus, challenging traditional gender stereotypes. Conscious decisions about gender are also found in picturebooks featuring more realistic, factual portrayals of wolves. Readers of Walk with a Wolf (Howker & Fox-Davies, 1997) follow the story of a female animal, the effect of which is to ‘naturalise the wolf as a wild fellow-spirit, a fierce but unthreatening presence in the child’s imaginative world’ (Hollindale, 1999: 106). This suggests that, compared with the male of the species, the female is benign and offers a fresh perspective of the wolf.

Aims and approaches to the research

In previous reader response research carried out with 7- to 11-year-old children, I noticed that the wolf and various wolf-related characters feature greatly in children’s literature. In particular, it was whilst focusing on Pennac’s (2002) novel Eye of the Wolf, which tells the sympathetic story of a wolf in captivity, that I realised the potential richness of the wolf as a character. Given this, I wanted to discover how children would respond to two picturebooks that depict wolves in quite different ways. Research by Arizpe and Styles demonstrates ‘the pleasure and motivation children experienced in reading [picturebooks], and the intellectual, affective and aesthetic responses they engendered in children’ (2003: 223). In light of this, the central aim of my research was for the children involved to engage with complex, at times, challenging picturebooks, to share their responses to the texts, and for them to develop as confident, autonomous and reflective readers willing to take risks as they responded to the texts. Louise Rosenblatt’s transactional theory states that readers continually make connections between their current reading, prior experience and sociocultural issues, bringing word and image to life: attention given to a text activates ‘certain reservoirs of experience, knowledge, and feeling’ in the reader (1978: 54). Given this, I hoped the children would share any existing experience and understanding of the wolf in folktales, fables, myths and legends, and their opinions of real wolves, alongside reading the chosen texts. I was interested to see how the children would draw on this knowledge in their discussions, and if their view of wolves might then change depending on representations encountered in the chosen picturebooks.

My research was carried out in a multi-ethnic primary school in Greater London. The participants were a group of six children (three boys and three girls) aged 10 and 11. They were chosen by the class teacher and identified as keen and competent readers, skilled in responding to a range of texts and able to make good use of inference and deduction. Each child was given their own copy of the picturebooks, which they took turns to read aloud to each other. I felt it was important for the children to spend time on sustained, close reading of the text, so as to enable active, critical interpretations. As they read, they were invited to comment on anything that interested them and discussion was encouraged by means of ‘literature circles’ (Short, 1997), whereby dialogue is used to orchestrate a community of enquiry and enthusiasm around books. Aidan Chambers states that ‘The art of reading lies in talking about what you have read’ (1985: 138), and conversation was further guided by the use of Chamber’s ‘tell me’ approach (1993), which encouraged the children to consider the books in more depth. Evans also states, ‘It isn’t enough to just read a book, one must talk about it as well’ (2009: 3). These shared response methods would enable children to take a joint, active and reflective role in developing their responses to picturebooks featuring the wolf.

Polysemy and counterpoint

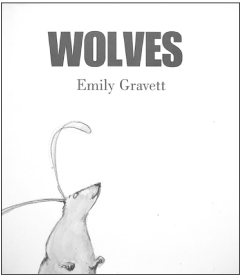

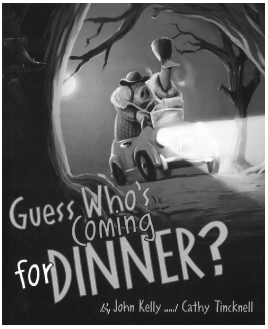

The two picturebooks discussed by the children were Wolves (2005), by award winner Emily Gravett, and Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner? (2004), by John Kelly and Cathy Tincknell. They were chosen for their polysemic nature, since they offer multiple opportunities for meaning-making. Sylvia Pantaleo explains how polysemy is brought about by ‘metafiction’, which ‘draws the attention of readers to how texts work and to how meaning is created’ (2005: 19). Metafictive devices in these picturebooks include: intertextuality; multiple narratives; illustrative framing; indeterminacy; and unconventional design and layout. Both picturebooks tell their story through counterpointing interaction, explained by Nikolajeva and Scott who state, ‘dependent on the degree of different information presented, a counterpointing dynamic may develop where words and images collaborate to communicate meanings beyond the scope of either one alone’ (2000: 226). This has an especial effect in engaging the reader’s imagination and eliciting various interpretations. In Wolves, the verbal text consists of facts about grey wolves, whereas the visual text simultaneously shows a rabbit’s experience of reading a book, whilst being unwittingly stalked by a wolf. A similar predator–prey relationship unfolds through counterpointing interaction in Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?. The words tell the story of the Pork-Fowlers, a pig and a goose, who accept a mysterious invitation to a weekend of fine dining. Unbeknown to them, they are the gourmet food: the reader can see their host, who happens to be a wolf, spying upon the unsuspecting couple, visible in each illustration but not mentioned by the text. In these polysemic picturebooks, readers are expected to provide meanings that are not directly conveyed by the words and images, but are merely implied. For reader response theorist Wolfgang Iser, this active engagement is at the centre of the reading experience, since there are gaps in the text which must be filled by the reader: ‘it is the gaps, the fundamental asymmetry between text and reader that give rise to communication in the reading process’ (1978: 167). Such gaps are particularly evident in picturebooks featuring counterpoint, because once words and illustrations are juxtaposed on the page they begin to influence and interact with each other. Iser’s (1978) notion of the ‘implied reader’ refers to one who can accept those invitations offered by the text, to participate in meaning-making. In my research, it was essential for children to take up the role of the implied reader so as to respond fully to these picturebooks.

Exploring children’s responses to Wolves

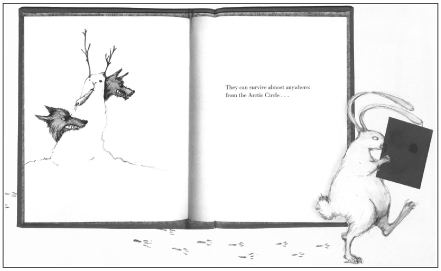

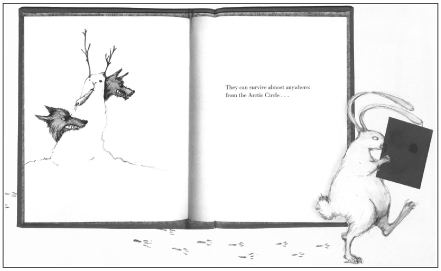

Emily Gravett has created a polysemic picturebook, which at face value tells a simple story of a rabbit reading a library book and being eaten by a wolf (Figure 10.1). Visual depictions of the wolf pack shift between anthropomorphic and realistic, so the portrayal of these animals is humorous, yet unsettling and sinister. Tension builds as the wolf steadily closes in on his unsuspecting victim, until launching the final brutal attack. It is through the reading event that the complexity of Wolves is revealed, as it explores boundaries between fantasy and reality, bringing attention to the text not just as a secondary world but as a real artefact in the reader’s hands. The ingenuity in the presentation of the story means that rabbit and the reader are drawn into the tale, while the wolf is drawn out. Gravett blends narrative and non-fiction, to play further with readers’ interaction and transaction with the text. The children began to interpret some of these complexities in the opening pages of Wolves (Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Wolves: ‘They can survive almost anywhere: from the Arctic Circle …’

| James: The wolves look mean, with sharp teeth and really angry eyes. They’re growling … |

| Oliver: At the rabbit, because they’re growling that way! |

| Emma: They’ve made the idea of packs literal. It says ‘they live in packs’ and they’re in a box. It’s a pack of wolves... in a pack! |

| James: Although the writing is factual, the story seems unrealistic because there’s a rabbit getting a book from the library … |

| Matthew: [Turns the page] It’s facts, but there’s something different going on in the pictures... the wolves are sneaking up on rabbit. They probably want to eat him! |

| Irayna: It looks like they’re spying on him. |

| Matthew: The wolves have probably come alive. They’ve made a snow-bunny to hide behind. I think rabbit will outsmart them! He’ll act like he doesn’t know... but really he does! |

| Emma: Maybe it’s part of their plan to attack rabbit... and when the snow-bunny melts, that’s when... well, they hope by the time it melts they’ll have killed rabbit! |

| Oliver: It’s a count down! |

| Hannah: Maybe they’re trying to hide behind the snow-bunny so the rabbit thinks it’s really another rabbit and doesn’t get afraid. |

Recurrent motifs of the wolf as fierce and threatening aligned with the children’s existing shared awareness of a common cultural archetype. Previous discussions had reflected their awareness of stereotypes of the wolf, both in folktales and reality, which the children had described as ‘sly predators, working systematically as a team’ and ‘wild creatures, living in forests, where they can be sneaky and hide easily’. The children had also discussed commonplace idioms featuring the wolf as being representative of trickery and isolation. They had suggested that ‘wolf it down’ makes reference to the wolf rather than any other animal because ‘that’s what wolves are like, starving hungry and ravenous: they eat quickly’. Their experience of idiomatic phrases shows how everyday language reinforces typecasts, to the extent that these depictions are taken to be the true behaviour of wolves. The children’s familiarity with stereotypes and idioms encouraged them to interpret the ‘snow-bunny’ as symbolic of the wolves’ calculated plan to pursue rabbit. This influenced their reading as they interpreted gaps in the text to predict the wolves’ intentions and the inevitability of rabbit’s situation.

| Oliver: The wolf might be coming out of the book, in the book. |

| Irayna: Here he’s dressed a bit like the wolf that eats Red Riding Hood’s grandma, like he’s in disguise. |

| James: I think he’s dressed like Red Riding Hood, because of the cape. |

| Hannah: Maybe there are loads of different wolves from other fairy tales in this book, and they’ll come out and try to get rabbit. |

| Matthew: Yeah, the wolf jumped out of Little Red Riding Hood and now he’s in this one! Maybe he’s eaten an old woman and put her clothes on to disguise himself, so rabbit won’t know. |

As the wolf pack begin to materialise from the pages of rabbit’s book, the children appreciated the ways in which visual and verbal texts were manipulated to convey meaning. Illustrations and context inspired references to traditional tales, bringing further preconceptions and ideals to the story. Gianni Rodari (1996) describes this intertextuality as ‘Fairy Tale Salad’, in which familiar folktales can be re-imagined in new and unexpected ways. This presupposes active participation in the reading process, because the reader must be the one to make such intertextual links, to develop the meaning of the story. The children’s impulse to distinguish between fiction and non-fiction was challenged by ‘counterpoint in genre’, as boundaries between text types were deliberately blurred (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2001: 24). Despite this, the nature of their discussion shows their desire to make sense of what they were seeing and to piece together a plausible narrative, and demonstrated that they were becoming more autonomous in their responses.

Rabbit meets his end... or does he?

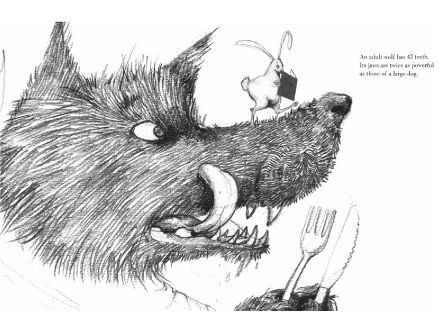

As the reader progresses through the book with rabbit, the wolves physically make their escape from the confines of the pages and take form in the world that rabbit occupies. Eventually, the reader is presented with one wolf, so huge that just his tail or legs occupy the entire page, and the reader can only imagine the actual size of this creature. This is achieved through the illustrative technique of frame-breaking, which allows the wolves to escape from the book, whilst inviting the readers ‘to step into the image and become an active part of the story’ alongside rabbit (Nikolajeva, 2008: 64). Tension grows, as certain images show the wolf to be particularly threatening, though rabbit is oblivious to the fact that he is being tracked. Thereby, the illustrations intruded into the children’s visual space, and consequently they felt they were being placed in rabbit’s position (Figure 10.3).

| Hannah: Because rabbit is reading the library book, and we see the same book when we’re reading, it’s like we are rabbit. A bit frightened! |

| James: [Turns the page] The wolf is really big! He takes up the whole page, looking right at you, close-up. |

| Irayna: Even though you can’t see all of the face or the body, you can tell he’s angry. It’s his eyes and maybe he’s licking his lips because rabbit is right there! |

| Oliver: [Reads ‘They also enjoy smaller mammals, like beavers, voles and …’] It’s going to say ‘rabbits’! [Turns the page] Oh, my goodness! What’s happened?! It’s Red Riding Hood! |

| Irayna: Oh... the book is torn! The wolf’s probably eaten rabbit! There’s a small piece of paper with the word ‘rabbit’ on it.... The book is shredded. The wolf probably did that. |

| Hannah: The book is red, meaning ‘danger’ for poor rabbit. |

| Oliver: And red like Red Riding Hood’s cape. Because she got away but rabbit hasn’t, in a way, it’s like Little Red Riding Hood is dead. |

This episode centres on ‘the drama of the turning page’ (Bader, 1976: 1), which built anticipation as the children watched rabbit’s predicament unfold, filling in the gaps between these pages to ascertain what had happened. Frame-breaking and the realistic image of rabbit’s book, ripped up, enhanced this dramatic moment in the story and caused the children to feel vulnerable and empathetic. Observing events from rabbit’s perspective invited them to interpret the episode as a metaphor for the fate of Little Red Riding Hood, who is usually saved by the huntsman. Their responses show how folktale symbolism can be reshaped and redeployed by both author and reader, to engender a fresh but still menacing view of the traditional wolf story.

An alternative ending: making a choice

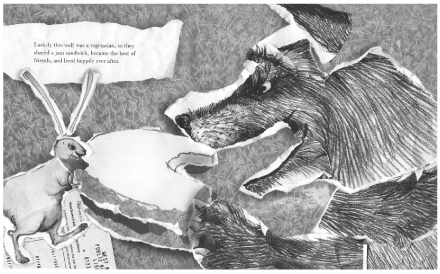

Having seen rabbit meet what seems to be a rather gruesome end, Emily Gravett presents an alternative ending ‘for more sensitive readers’ (2005: unpaginated), in which rabbit is not eaten. Instead, he and the wolf supposedly become friends and live happily ever after. The book continues to work in a contrapuntal way so that the reliability of this conclusion is ambiguous and the choice of two endings challenges readers. Lawrence Sipe and Sylvia Pantaleo state that in such cases, ‘readers are invited to generate multiple, often contradictory interpretations and to become co-authors’ (2008: 4), and I was interested in how far the children were able to assume this position, as they discovered and attempted to make sense of this second ending (Figure 10.4) (Plate 28).

| Emma: Phew! The wolf’s teeth have gone! No need for sharp teeth now he’s vegetarian. |

| James: I think he actually does have teeth; see the white. But instead of pointy, they’re smooth because he’s vegetarian... I don’t think that bit about the jam sandwich is true, because rabbit’s neck is cut in half. |

| Emma: You know how the wolf came out of the book to eat rabbit... well, maybe the wolf went back inside just before book got destroyed, so he’s stuck in there and can’t get out again. |

| Matthew: Look, the next page! There’s a letter from the library... and loads of letters for rabbit. He hasn’t got them, because he’s dead! Oh! |

| Irayna: It looks like the wolf destroyed rabbit, and because the book got destroyed, he got destroyed too. So they put the pieces back together like it was before. Then they ate a sandwich! |

| Matthew: Sometimes, when you read a book and you know what’s going to happen, you want to tell the character to do the right thing! I wanted to read on because I thought rabbit would do something smart to survive, like a karate chop! |

To comprehend the finale, the children needed to suspend their commitment to either of the two endings until their relative credibility could be judged. This was somewhat unsettling, as they were not entirely sure what had occurred or which version of events to take as true. In attempting to figure out the actual fate of rabbit and the wolf, they considered the world within and outside of the library book, offering explanations for the blurring between the represented realms of fantasy and reality. The alternative endings invited the children to predict, invent and even wish for other outcomes, and their comments reflect their vested interest in the characters and plot.

| James: At the start, when rabbit is in the library, there’s a bookshelf with a rabbit book sticking out. It’s as if the wolf has been there and maybe borrowed a book about rabbits. |

| Irayna: Maybe the wolf took it, to find out about rabbits. Then he put it back. |

| Oliver: Perhaps the wolf made the Wolves book poke out a little bit, so the rabbit would take it, and then the wolves could come out and get him! |

| Matthew: Here’s one of those borrowing cards you get in library books. There are loads of dates... it’s a popular book! |

| Hannah: Because this book has been borrowed loads, the wolf must have eaten a lot of rabbits! |

Perry Nodelman argues that each text calls for an ‘implied viewer’, who can attend to the ‘apparently superfluous pictorial information [that] can give specific objects a weight beyond what the text suggests’ (1988: 106). On rereading, the children noticed such details in the illustrations at the very beginning of Wolves, inviting them to embellish the story. It was only having read the whole book that the children could revisit and interpret these supplementary details, to create possible events not actually mentioned in the text. The children’s ideas reinforced their interpretation of Gravett’s wolves as unremitting predators that had set into action a plan to catch rabbit before the story itself had even started. The appeal of Wolves as a physical artefact prompted them to interpret the library docket and date stamp sheet: Hannah’s sincere yet whimsical suggestion, that the wolves had been around a long time and had already devoured several other rabbits, uses metafictive devices to take the story beyond the page. Such engagement with the text shows how development of reader response enables children to understand and critique literature.

Exploring children’s responses to Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?

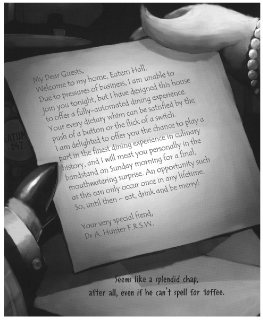

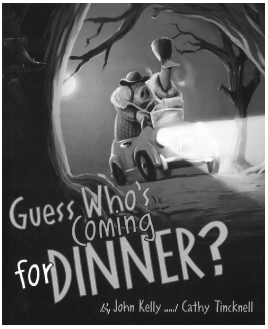

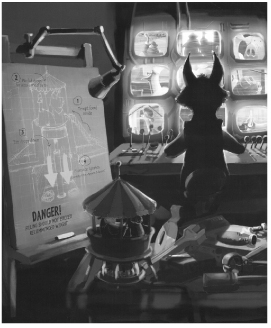

Having read Wolves, which centres on archetypes of the wolf as a successful predator, the same children then read Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner? (Figure 10.5). Elements of this picturebook echo the classic version of The Story of the Three LittlePigs (Jacobs, 1843), wherein a wolf successfully preys upon two pigs but is ultimately undone by the third little pig, into whose cooking pot he falls and is himself turned into supper. Similarly, in Kelly and Tincknell’s picturebook the wolf’s potential victims are a pig and goose. Their predator, Hunter, builds an elaborate contraption designed to ensnare and cook his dinner, but through a series of mishaps it is he who ends up baked in a pie and eaten by his fellow pack mates. Such traditional themes offer children renewed perspectives of conventional stories. Despite his namesake, Hunter is flawed, and his supposed status as an evil genius establishes this story as a spoof of the mystery genre. This plot development takes place gradually; to begin with the wolf is conventionally cunning and devious. In reading Hunter’s note to the Pork-Fowlers, the children recognised clues in the language which enabled them to appreciate the underlying meanings and ironic tone (Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.5 Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner? (Kelly & Tincknell, 2004).

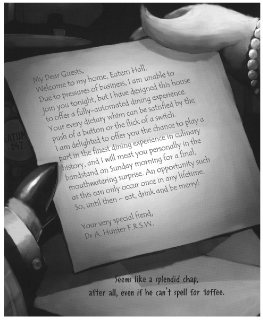

| Emma: It says ‘meat’ as in the meat you eat, instead of ‘I will meet you personally’. |

| Hannah: And, ‘Your very special fiend’ instead of ‘friend’. |

| Irayna: Like he’s the enemy! |

| Matthew: The wolf is good with his spelling. He’s doing it on purpose... very sneaky! |

| Irayna: But the Pork-Fowlers think Hunter ‘can’t spell for toffee’. |

| Emma: It’s a huge clue! |

| Irayna: It says ‘eat, drink and be merry’, so he’s telling them to eat more, but that’s just so they’ll get fatter and he’ll have more meat. |

Figure 10.6 Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?: A note from Hunter.

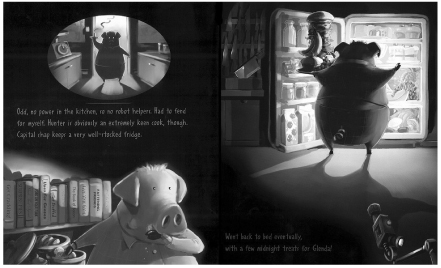

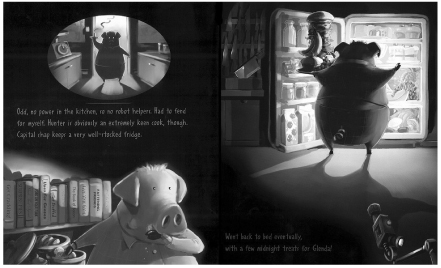

As children engage with texts, they discover more about language as ‘a rich and adaptable instrument for the realisation of... intentions’ (Halliday, 1969: 27). Metafictive features such as this note from Hunter offer readers the opportunity to see how language can be manipulated according to audience, purpose and context. A few pages on, the children saw Horace Pork-Fowler visit the kitchen for a midnight snack (Figure 10.7). Their comments show their ability to read the pictures and the words, both separately and together, so as to engender thoughtful interpretations.

| James: In the background there are two diagrams of a pig and goose, like in a butcher’s shop. It’s the best parts of meat! |

| Emma: Hunter has been reading all these cookery books, preparing to cook the pig and the goose! |

| Matthew: Yeah, ‘Cook your Goose’... They’re definitely in trouble. Their goose is cooked! |

| Oliver: ‘Meals that Squeal’ and ‘Get Stuffed’! |

| Irayna: They’re funny; quite cheeky. A lot of them rhyme... ‘Let’s Talk Pork’! |

| James: ‘Fattening Friends’! On the other page there was a poster saying ‘PieFeast this Sunday: Wolf it down!’, so I think the wolf will kill the fattened pig and goose, then he’ll put them in a pie and eat them! |

| Matthew: He likes only the best meat. Gourmet food! |

| Hannah: It says ‘no power in the kitchen’, but the fridge is working … |

| Irayna: There has to be some light otherwise the pig wouldn’t be able to see clearly... all that food! |

| Oliver: Oh, I know what the wolf’s done! The main light is not on because there might be loads of secret stuff about how to cook the pig and goose, which the wolf doesn’t want them to see, but he does want the pig to find the fridge and eat more. So the fridge has been lit up. |

| Matthew: Like heaven... Food heaven! |

Figure 10.7 Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?: Horace Pork-Fowler’s midnight snack.

The children took pleasure in reading aloud Hunter’s cookery book titles, appreciating how alliteration, pun and rhyme contributed to humour. Language thereby became a source of play. The children noted the relevance of these recipes to the characterisation of the wolf as a voracious yet comical villain, as the books pointed openly at his scheme to prepare a pie feast. Through shared dialogue, they reasoned beyond the text, interpreting the illuminated food store to be part of Hunter’s elaborate plans. Margaret Meek states, ‘When we want to make new meanings we need metaphor... the words mean more than they say’ (1988: 16). Matthew’s own use of the metaphor, ‘food heaven’, showed his understanding of the pig’s disposition, for whom a full fridge really is heavenly, and affirmed his awareness of the wolf’s intentions. Vocabulary encountered elsewhere in the book, such as the word ‘gourmet’, filtered into the children’s discussion, and their responses to familiar idioms including ‘wolf it down’ reinforced stereotypes of the wolf as a carnivore and a glutton. The story contributed significantly to the children’s linguistic development, enabling them to appreciate subtleties in vocabulary and to use language with dexterity and playfulness.

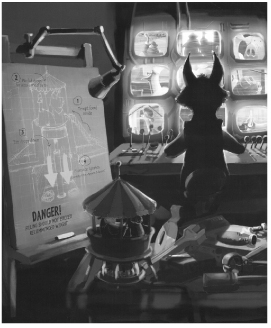

Reviewing and rereading plus a serving of wolf pie

Lawrence Sipe observes how reviewing and rereading picturebooks allows children to have ‘multiple experiences as they engage in creating new meanings and constructing new worlds’ (1998: 107). This continued meaning-making shifts between words and pictures as the reader assimilates new information, a process that Sipe (1998) refers to as ‘transmediation’. Visual and verbal texts are of equal significance in this process, seen in the children’s discussion as they revisited certain pages to make sense of events in Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?

| James: In the picture you can see pie-crust under the top of the bandstand. |

| Irayna: Didn’t we see a model of that bandstand before, and a miniature goose and pig inside it? |

| Matthew: I think something will release, and the roof will drop down on those two. |

| Oliver: No, I think actually what’s happening is... look... it’s dropping on the wolf. |

| Emma: Oh! Hunter is being cooked, because see this picture... he’s going up the ladder into the tin. Then the contraption works... but instead of the pig and goose being caught, it’s Hunter! |

| Oliver: Yeah, it says ‘searched for Hunter but couldn’t find him’... He was trapped underneath! |

| Irayna: But the pig or the goose don’t even realise what’s happening... No, not a clue! It shows you what’s happening to the wolf in the pictures. Without the pictures it would be a very different story, because we wouldn’t know what’s really happening! |

On rereading, the children benefitted from looking back and forth through the book autonomously and talking through their ideas as a group. Details within the pages thereby gained fresh relevance and contributed to a fuller understanding of the wolf’s scheme. Even though the various characters were clueless as to what was really happening to one another, the children were in the know, which empowered them as they explained the consequences of Hunter’s misdemeanours (Figure 10.8).

| Hannah: On one of the earlier pages there’s a ‘Bed-o-Scales’ to show if the pig is heavy enough... if he’s ready to eat! |

| Oliver: And here, the wolf is hiding under the trap door... looking at that arrow on the ‘Bed-o-Scales’! |

| Emma: The dial is just on the line of being too heavy... it says somewhere... here, on the wolf’s blueprint, ‘DANGER! Filling should not exceed recommended weight’. |

| Irayna: Oh no, the arrow is near the red! Unless the wolf eats him soon, he might be too heavy. He’ll need to go on a diet! |

| Matthew: But the pig ate too much food, so the machine broke! |

| Irayna: His plan didn’t work because the Pork-Fowlers were too smart for him. |

| Matthew: No, they didn’t know... the Pork-Fowlers just walked off by accident. |

| Hannah: They left a bit earlier than the wolf expected. |

| Emma: The pig and goose ate more than they were supposed to... and Hunter didn’t know! |

| James: [Reads] ‘I wonder what sort of pie they’re having?’ |

| Matthew: Wolf pie! Look, there’s an empty seat for him! I think that’s the wolf’s family, the rest of his pack. |

| Hannah: They’re eating the pie, but they don’t know Hunter is inside! |

| Irayna: Poor wolf... I’ve realised he’s not going to get what he wants... |

| Oliver: Hunter was clever because he tricked the Pork-Fowlers into eating loads of food. But he’s not so clever because he’s been turned into a pie by his own machine! |

Figure 10.8 Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner?: Hunter’s surveillance room.

The children had the confidence to experiment with genre-specific vocabulary (‘machine’, ‘contraption’, ‘blueprint’) and adopted unusual concepts from the book in their responses (‘Bed-o-Scales’, ‘wolf pie’). They assumed the perspective of the characters, even going into role to imagine what the wolf pack might be thinking as they watched their dinner disappear. Hunter’s incompetence and ultimate undoing generated real sympathy, perhaps partly evoked through the metaphorical subversion of his traditional-wolf counterpart, who at least tends to get a decent meal before meeting his end. The children followed the irony generated through counterpoint in perspective: the verbal text that chronicles the Pork-Fowlers’ weekend retreat emphasised the naïvety of these characters, while the illustrations quite literally showed the wolf’s vantage point, through binoculars, periscopes and CCTV footage. Despite his well-laid plans and self-portrayal as a criminal mastermind, the children knew that Hunter was never a serious threat, because his plot to eat his guests was wholly exaggerated and the source of much humour. Pantomime features such as these ensure significant collaboration between reader, author and illustrator, and the children’s responses articulate their appreciation of the different meanings derived from the written text and the pictures.

Conclusion: reflections on the reading process

Wolves and Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner? are powerful examples of the function of literature to provoke, puzzle and challenge, as they each portray wolves in very different but thought-provoking ways, challenging the reader to talk beyond the page (Evans, 2009). By deliberately contradicting the information and viewpoint provided by the text, the pictures create intensely dramatic situations, to convey the climax of the hunt in one story, and the wolf’s theatrical undoing in the other. The children’s growing awareness of this ironic dissonance between words and pictures was evident, as they willingly engaged in playful re-negotiation of meaning. Since these texts demand a substantial degree of openness, flexibility, and cognisance in their audience, time spent on sustained, close reading was essential for encouraging active and critical interpretations. Drawing on the children’s knowledge of stories brought to light a shared cultural heritage, founded on archetypes of the wolf within traditional tales. These enriching aspects of the children’s prior experience proved to be beneficial when reading the picturebooks, as the recasting and subversion of familiar characters and themes revived the children’s interest in folktales, challenged stereotypes and invited them to make intertextual links. The children realised that although both stories were propelled by the wolf characters’ intentions to hunt and eat, these creatures had different characteristics and their endeavours resulted in varied degrees of success. Depending on which picturebook representation they encountered, the children’s initial impressions of the wolf as a fearsome beast did change. Responses to Gravett’s wolves and then to Hunter, ranged from fear to sympathy, although a sense of humour was always evident both in the texts themselves and the children’s discussions. Empathy for certain characters deepened the children’s involvement with the stories, as seen in their reactions to rabbit’s predicament and Hunter’s demise.

Wolfenbarger and Sipe identify three main impulses that guide children’s responses to polysemic picturebooks: the ‘hermeneutic impulse’ or the desire to interpret the text; the ‘personal impulse’, which connects stories to one’s own life; and the ‘aesthetic impulse’, which ‘pushes reader’s creative potential to shape the story and make it their own’ (2007: 277). As my research shows, each of these impulses was evident within the children’s responses, as metafictive devices enhanced their experiences as readers of polysemic picturebooks. Further to this, it was the richness of the context, the wolf itself, which enabled children to reflect so thoughtfully upon their interpretations, and consequently on the act of reading. Since our relationship with the wolf is steeped in history and culture, diverse, unexpected and controversial representations of this animal will continue to challenge children to read at abstract levels of understanding. For renowned wolf biologists David Allen and L. David Mech, hearing the wolf pack howl is ‘a mass chorale of resounding splendour... the grand opera of primitive nature’ (1963: 202). Conversely, Peter Hollindale (1999) notes that the sound of wolves is shorthand for terror in stories for children, their howls frequently sending a shiver up the reader’s spine. Whichever view is favoured, wolves still abound in contemporary children’s literature, as authors and illustrators continue to create polysemic, challenging picturebooks that affirm this creature’s enduring hold on the imaginations of both children and adults.

Academic references

Allen, D.L. & Mech, L. D. (1963) Wolves Versus Moose on Isle Royale, National Geographic, 123(2): 200–219.

Arizpe, E. & Styles, M. (2003) Children Reading Pictures: Interpreting Visual Texts. London: Routledge.

Attenborough, D., Berlowitz, V. & Fothergill, A. (2011) Frozen Planet [Documentary] BBC and The Open University. www.bbc.co.uk/nature/life/Gray_Wolf

Bader, B. (1976) American Picture Books: From Noah’s Ark to the Beast Within. New York: Macmillan.

Beckett, S.L. (2014) Revisioning Red Riding Hood Around the World: An Anthology of International Retellings. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Bettelheim, B. (1975) The Uses of Enchantment. London: Penguin Books.

Brewer, E.C. (1995) Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. London: Cassell Publishers.

Chambers, A. (1985) Booktalk: Occasional Writing on Literature and Children. London: The Bodley Head.

Chambers, A. (1993) Tell Me: Children, Reading and Talk. Stroud: Thimble Press.

Evans, J. (2009) Talking Beyond the Page: Reading and Responding to Picturebooks. London: Routledge.

Grimm, J. & Grimm, W. (1812) ‘Little Red Cap’, in Zipes, J. (ed.) (1993) The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. London: Routledge.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1969) Relevant Models of Language, Educational Review, 22(1): 26–37.

Hollindale, P. (1999) Why the Wolves Are Running, The Lion and the Unicorn, 23(1): 97–115.

Hourihan, M. (1997) Deconstructing the Hero. London: Routledge.

Iser, W. (1978) The Act of Reading. London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jacobs, J. (1843) The Story of the Three Little Pigs, in Tatar, M. (2002) The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. New York: Norton and Company.

Jung, C.G. (1978) Man and his Symbols. London: Picador.

Jung, C.G. (2010) The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. London: Routledge.

Lopez, B.H. (1978) Of Wolves and Men. New York: Scribners.

Marvin, G. (2012) Wolf. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Meek, M. (1988) How Texts Teach What Readers Learn. Stroud: The Thimble Press.

Mitts-Smith, D. (2010) Picturing the Wolf in Children’s Literature. New York: Routledge.

Nikolajeva, M. (2008) Play and Playfulness in Modern Picturebooks, in Sipe, L.R. & Pantaleo, S.J. (eds) Postmodern Picturebooks: Play, Parody, and Self-Referentiality. New York: Routledge.

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2000) The Dynamics of Picturebook Communication, Children’s Literature in Education, 31(4): 225–239.

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2001) How Picturebooks Work. New York: Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words About Pictures – The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Pantaleo, S. (2005) Young Children Engage with the Metafictive in Picture Books, Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 28(1): 19–37.

Perrault, C. (1697) ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, in Zipes, J. (ed.) (1993) The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. London: Routledge.

Prokofiev, S. (1936) Peter and the Wolf [Music]. USA: RCA Victor.

Rodari, G. (1996) The Grammar of Fantasy: An Introduction to the Art of Inventing Stories. Translated from French by Zipes, J. New York: Teachers and Writers Collaborative.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1978) The Reader, the Text, the Poem: The Transactional Theory of Literary Work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Short, K.G. (1997) Literature as a Way of Knowing. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Sipe, L.R. (1998) How Picture Books Work: A Semiotically Framed Theory of Text-Picture Relationships, Children’s Literature in Education, 29(2): 97–108.

Sipe, L.R. & Pantaleo, S.L. (eds) (2008) Postmodern Picturebooks: Play, Parody, and Self-Referentiality. New York: Routledge.

Templeton, S. & Prokofiev, S. (2006) Peter and the Wolf [Film]. Warsaw: Breakthru Films.

Wolfenbarger, C.D. & Sipe, L.R. (2007) A Unique Visual and Literary Art Form: Recent Research on Picturebooks, Language Arts, 84(3): 273–280.

Zipes, J. (1993) The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. London: Routledge.

Children’s literature

Aesop (1919) Aesop’s Fables for Children. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Company.

Barbalet, M. & Tanner, J. (1992) The Wolf. New York: Macmillan Publishing Group.

Bloom, B. & Biet, P. (2001) A Cultivated Wolf. London: Siphano Picture Books.

Egnéus, D. (illus.) (2011) Grimm, J. and W. (unabridged text) (1812) Little Red Riding Hood. New York: Harper Design.

Forward, T. & Cohen, I. (2005) The Wolf’s Story: What Really Happened to Little Red Riding Hood. London: Walker Books.

Gravett, E. (2005) Wolves. London: Macmillan.

Howker, J. & Fox-Davies, S. (1997) Walk with a Wolf. London: Walker Books.

Innocenti, R. (2012) (translator Frisch, A.) The Girl in Red. Mankato, MN: Creative Editions.

Kelly, J. & Tincknell, C. (2004) Guess Who’s Coming for Dinner? Dorking, Surrey: Templar Publishing.

Kipling, R. (1894) The Jungle Book. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Leray, M. (2010) (translator Ardizzone, S.) Little Red Hood. London: Phoenix Yard Books.

Maclear, K. & Arsenault, I. (2012) Virginia Wolf. Toronto: Kids Can Press.

Morris, J. & Hyde, C. (2013) Little Evie in the Wild Wood. London: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Paver, M. (2004) Wolf Brother: Chronicles of Ancient Darkness. London: Orion.

Pennac, D. (2002) (trans. Adams, S.) Eye of the Wolf. London: Walker.

Roberts, L. & Roberts, D. (2005) Little Red: A Fizzingly Good Yarn. London: Pavillion Children’s Books.

Santangelo, C.E. (2000) Brother Wolf of Gubbio: A Legend of Saint Francis. New York: Handprint Books.

Scieszka, J. & Smith, L. (1991) The True Story of the Three Little Pigs. London: Puffin.

Sendak, M. (1963) Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper and Row.