Figure 5.1 The Wolves in the Wall by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean (2003).

What are they and where have they come from?

This chapter will define what fusion texts are, prior to looking at their evolution with reference to comics, graphic novels and picturebooks. It will look at some of the difficulties of terminology, audience and content before focusing in particular on the work of Dave McKean, both alone and in collaboration with other authors and fusion text creators. The chapter will argue that fusion texts are challenging, often troubling texts in both their content and illustrative style but that as a genre they are here to stay.

... the narratives of McKean’s books are constructed through a powerful fusion of generic conventions, a combination that prompts the reader to stay constantly alert, assessing the nature of word – image interaction on each page, and switching from one mode of interpretation to another.

Panaou & Michaelides (2011: 66)

There will be some kind of visual text – a comic, graphic novel, picturebook or illustrated text to suit most readers. Additionally, there is now a new kid on the block! A different kind of book is emerging, one that exhibits some, but not always all, of the characteristics normally thought of as belonging to comics, graphic novels and picturebooks. These books blur the boundaries, blending the characteristics of visual texts to create ‘a category that is a synthesis of aspects from all of them’ (Evans, 2011: 53). These are ‘fusion’ texts.

Fusion texts are the evolving multifaceted and multimodal close relation of comics and graphic novels and their characteristics show a merging of features from comics and graphic novels with those from picturebooks where text and image work together in harmony or discordantly. This is resulting in a form of cross-breed, hybrid text which is breaking new ground in terms of visual texts and which is providing the platform for many innovative author/illustrators to be inventive with their thoughts and ideas.

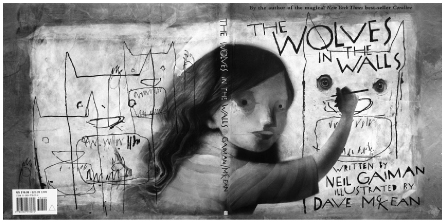

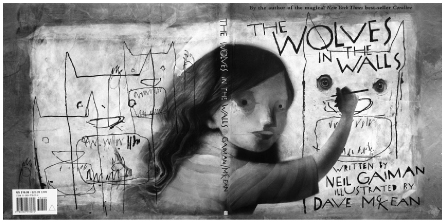

The Wolves in the Walls by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean (2003) is one such text (Figure 5.1). It was inspired by a nightmare that Gaiman’s 4-year-old daughter had that there were wolves in the walls of their house. It is an unusual, somewhat disturbing story that the reader knows is unbelievable but somehow it seems believable. In illustrating the book, McKean utilises many different techniques, including drawing, computer-generated imagery, photography and photomontage, to achieve an effect that complements but at the same time often fragments the text.

Ten-year-old Edward summarised the story:

The Wolves in the Walls is about a family in a big house that has wolves in the walls. One night the wolves come out of the wall and chase the family out of the house. The wolves cause chaos and mischief and a massive mess. After a while the family retake the house and tidy the mess. But now... strange elephant noises are coming from... the walls! This book makes the reader think of whether the wolves are real or imaginary or whether the family is scared of noise!

Edward

The Wolves in the Walls is a true fusion text, the cover implies that something really is in the walls of Lucy’s house but the pencil in her hand and the childlike drawing makes the viewer question if the wolves are real or not. Yet in playing with these thoughts we note that the eyes of the wolf are disturbingly real... are they real? In fact they are more real than real, they are hyperreal (see Figures 5.1 and 5.4)

Jeff Garrett states, ‘Hyperrealism is art that is convincingly real, but so real in our perception of it – so uber-real or hyperreal – that we are drawn to it with our eyes open. Hyperrealism is therefore not trickery, but seduction’ (Garrett, 2013: 149).

Figure 5.1 The Wolves in the Wall by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean (2003).

Fusion texts very often include this element of seduction! The ‘real’ wolves’ eyes are looking out at the viewer in a penetrating manner. They draw the viewer inwards making them wonder what is inside, what are the wolves doing and where does the girl come in? The eyes look real and therefore are real in our minds, even though we know they are not real and in fact, never existed. In writing about hyperrealism Umberto Eco (1986) considered the viewer’s faith in fakes whereby false things are created to look more real than real... made to look hyperreal.

It is evident that McKean is a practitioner of hyperrealism, he uses traces of hyperrealism in his work, ‘melding incredibly, credibly real and fantastic elements into a convincing new whole transcending the confused and flawed versions of truth we experience in our real-world existences’ (Garrett, 2013: 148).

In looking at the artificial perfection of the real in hyperrealism, Garrett considers how surrealism as an art movement also gives us ‘blatantly real, indeed impossible images made of realistically portrayed building blocks, that combined seem to correspond to a different – and even higher – form of reality’ (2013: 155). McKean’s art is this kind of art, a fusion of differing realities that draw the reader into thinking that what is being viewed is believable when we know it is unbelievable.

Young readers are able to pick up these hyperreal/surreal fused nuances, which in this picturebook lead them to question if the story could actually be real. Having illustrated the book cover (Figure 5.2),

Figure 5.2 Ten-year-old Molly’s illustration for the book cover of The Wolves in the Walls.

This book is great. The pictures are not like normal pictures in picturebooks they are a combination of cartoons, photographs and drawings with words everywhere, not just going from one side of the page to the other but up and down and across the page. It’s a bit like a comic with speech bubbles and little boxes everywhere. My favourite pages are where the wolves come out of the walls – that’s scary –and where the wolf plays the trombone I also like it at the end where Lucy talks to pig puppet [Figure 5.3] [Plate 21].

Molly

In a close consideration of Dave McKean’s art, Panaou and Michaelides looked at how it ‘breaks conventions, resists categorisation, subverts reading expectations, and yet is highly successful in communicating powerful and engaging stories’ (2011: 63). They noted that The Wolves in the Walls is the kind of visual text whereby the viewer has to suspend belief as they interact with the book:

One could say that the walls represent the borders between reality and fiction, which the mind can easily transgress, as Lucy does, and as the creators of the book do, showing that there are really no borders. The relations and contrasts between text and illustrations are so intense, and the combinations and alterations so vivid, that you have to go along and agree with them.

Panaou & Michaelides (2011: 66)

The wolf’s eye looking from inside the walls symbolise the borders between reality and fiction, our mind tells us the eyes are real... maybe there are no real borders (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.3 (Plate 21) The Wolves in the Wall: The wolves came out of the walls.

Comics and graphic novels are still viewed, by many, in a different light to picturebooks. They have been the catalyst that has turned many children and adults, who could read, but didn’t want to, into readers. Countless numbers of children and young adults love to read them and yet they are still seen by many as the poor relation of other written and illustrated texts. Although both genres show a strong unity between word and image, they do not share the same ideological frameworks. Picturebooks can serve a pedagogical function, they celebrate socially prized literacy – the teaching of reading – whilst comics are seen as being against, indeed even obstructing, this highly prized type of literacy (Hatfield & Svonkin, 2012). Joseph states that comics, in particular alternative comics, can actually disturb the reader as they resist the norms of book culture and subvert the notion of children’s literature (Joseph, 2012).

Things are changing. A new breed of visual text is emerging, the fusion text. It is a ‘new kid on the block’, one that is presenting challenging and thought-provoking reading material in creative, artistic forms.

It was Will Eisner, the legendary cartoonist and author of Comics and Sequential Art, and the man who pioneered the comic-art field, who noted that since the 1980s things have changed radically and comics and graphic novels are now much more widely accepted, with the genre being extensively studied and researched academically. He was aware that ‘sequential art’ had been ignored for many decades for reasons linked to ‘usage, subject matter and perceived audience’. In attempting to identify some of the reasons for the evident lack of status, Eisner noted, ‘unless more comics addressed subjects of greater moment they could not, as a genre, hope for serious intellectual review...“great artwork alone is not enough”’ Eisner (1985: xi).

It was whilst writing his seminal text, Comics and Sequential Art, that Eisner came to the conclusion that the reason this genre had taken so long to be critically accepted wasn’t just the fault of the reading critic but was also the fault of the actual practitioner; the creator of sequential art. In his role as teacher of Sequential Art at the School of Visual Arts in New York in the 1980s, Eisner noted that many practitioners produced their art intuitively but that, ‘Few ever had the time or the inclination to diagnose the form itself’ (1985: xii). In thinking about this complex genre and the reasons for its lack of acceptance, Eisner realised that he was involved with ‘an “art of communication”, more than simply an application of art’ (1985: xii). The whole genre needed to be analysed and taken more seriously and Eisner soon began to recognise that an increasing number of artists and writers were creating sequential art that was more worthy of scholarly discussion.

This issue of subject matter and content was picked up by Scott McCloud, who, writing ten years later, had similar concerns:

Some of the most inspired and innovative comics of our century have never received recognition as comics, not so much in spite of their superior qualities as because of them. For much of this century the word ‘comics’ has had such negative connotations that many of comics’ most devoted practitioners have preferred to be known as ‘illustrators’, ‘commercial artists’ or, at best, ‘cartoonists’! And so, comics’ low self-esteem is self-perpetuating!

McCloud (1994:18)

Working at the same time as Eisner and McCloud, and in agreement with them, Raymond Briggs, creator of cartoon strips, graphic novels and picturebooks for readers of all ages, was aware that people often viewed the genre with contempt. He felt that it was the subject matter of many graphic novels, along with the terminology afforded to them, that posed the problem. Many of them did not deal with worthwhile subjects nor were they as widely read in England as they were in other countries where they had long been celebrated as worthwhile texts.

The status of comics and graphic novels is growing and although they have always been valued amongst a certain readership they are now much more widely accepted (Arnold, 2003; Couch, 2000; Evans, 1998, 2009, 2011; Gravett, 2005; Lim, 2011; Martin, 2009; Tarhandeh, 2011). There is, however, still an issue with the terminology of the genre, with many librarians and booksellers being unsure of where to position them on their shelves; should they be placed alongside children’s literature, young adult or adult literature, picturebooks, illustrated or chapter books? This question in itself poses a problem in terms of accessibility. Where do prospective readers look to find their preferred genre? The issue of terminology is not straightforward and even the great masters of the craft such as Will Eisner, Scott McCloud and Raymond Briggs have concerns about the terms being used.

In talking about the republished version of one of his earlier graphic novels, Gentleman Jim, Briggs shared some of his concerns with the terminology:

It’s jolly good, a book from 28 years ago being dragged out of the cellars. I read it the other day for the first time in years. I didn’t think it was bad, though I don’t see that it was all that revolutionary in terms of the graphic novel. Not that I like that term; they’re not all novels, and ‘graphic’ is such a meaningless word; it just means writing. I prefer the French, bandes dessinées. If you say strip cartoons, which is what I say, it implies something a bit comic and Beano-ish. It’s never been an accepted form in England, that’s the trouble. I’ve been grumbling about this for years.

Briggs (2008)

Shaun Tan also considered this question of terminology and in an article on graphic novels he stated:

You’ll notice that I use the terms ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’ interchangeably, because I don’t see much difference between them; these terms both describe an arrangement of words and/or pictures as consecutive panels on a printed page (and can be extended to include picturebooks too).

Tan (2011: 2)

Comics are an art form that features a series of static images in sequence, usually to tell a story. Eisner (1985) called comics ‘sequential art’. He studied and wrote about comics until his death in 2005, demonstrating that comics have a vocabulary and grammar in both prose and illustration. He also considered what needed to be in place for a visual text to be called a comic. How were comics different from other visual texts? He realised that creators of comics use a blend of words and images to convey their message; he also noted that many comics creators were artists presenting their work in ‘a series of repetitive images and recognisable symbols’, hence the term ‘sequential art’ (Eisner, 1985).

Scott McCloud extended Eisner’s work in relation to defining the art of comics. His eventual definition was more complex, stating that ‘comics are juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer’ (McCloud, 1994: 9).

The key to comics is their format, what they look like on the page. Traditionally they have been printed on paper with boxes of drawings in sequence. Text is usually incorporated into the images, with text bubbles to represent speech and squiggly lines to indicate movement. Well-known examples showing these characteristics are comics such as The Beano, Peanuts, The Simpsons, and even Rupert Bear, which uses a sequential art format but with a less cartoony style of art and which has been continuously in print for over 90 years since its conception in 1920.

It was Eisner’s book A Contract with God which was the first published graphic novel to use the term on its cover in 1978, despite the fact that Eisner, like others, disliked the term graphic novel and preferred to use the terms, ‘graphic literature’ or ‘graphic story’. Similar to comics and strip cartoons in form, the graphic novel, often defined as a type of comic, slightly longer than the typical comic, but produced in book form with some kind of thematic unity, is a truly multimodal form of communication. Weiner (2001) defines the graphic novel as ‘a story told in comic book format with a beginning, middle and end’, whilst de Vos (2005) defines them as ‘bound books, fiction and non-fiction, which are created in the comic book format and are issued an ISBN’. Philip Pullman questioned whether the terminology actually matters and in speaking of the graphic novel he stated: ‘Personally, I’m getting a little tired of the term. It’s the form itself that is interesting, the interplay between the words and the pictures, and I’d be happy to call them comics and have done with it’ (1995: 18).

Certain countries and cultures recognise this form of visual text more than others: these include France, with its celebrated bande dessinées including The Adventures of Tintin and Asterix the Gaul, and Japan with its widely read manga texts; manga being the Japanese term for comics. In Korea, Manhwa, the general term used to refer to comics and graphic novels was originally derived from Japanese manga (Lim, 2011).

Graphic novels have been viewed by some as dealing with unoriginal, immature and clichéd subject matter, lacking proper storylines and sometimes being limited to violent and sexually explicit graphics. Mel Gibson stated:

Graphic novels, comics and manga are often seen as texts specially for younger male reluctant readers, but such an assumption underestimates this enormously flexible medium as it can be used to create complex works of fiction or non-fiction for adults and young adults, male and female, as well as humorous stories for the very young.

Gibson (2008)

Briggs was in agreement but in complaining that graphic work doesn’t get the respect it deserves he sensed a change. In conversation with Nicholas Wroe, he stated:

Partly it has itself to blame because the subject matter is often so dreadful and there is still an awful lot of sock-em-on-the-jaw stuff going on. But respectable publishers are putting out graphic novels, although I don’t know if I like that term too much, and there is no reason why it shouldn’t be as dignified a medium as, say, film, which they are very much like in many ways.

Wroe (2004)

In order to be given greater consideration and respect, graphic novels need to deal with ‘subjects of greater moment’ (Eisner, 1985). Those published more recently cover issues ranging from eating disorders, war, and the holocaust to child abuse and drug addition:

It isn’t just recently published graphic novels that deal with challenging subject matter. As early as 1992 Art Speigelman won the Pulitzer Prize for Maus, a book about his father’s survival in the holocaust (Spiegelman, 1973). Maus is often noted as being the quintessential graphic novel. Then in 1982, Raymond Briggs wrote When the Wind Blows. In warning of the atrocities of nuclear war in the cold-war era and the influence of political propaganda on ordinary people, this graphic novel/fusion text was considered so important and influential that copies were sent to every member of the House of Commons in England.

It is apparent that there are many similarities between graphic novels and picturebooks, but although graphic novels can evidently be viewed as picturebooks, it is obvious that picturebooks cannot necessarily be viewed as graphic novels: the terms are not mutually inclusive. In the best examples of its genre a picturebook can be seen as ‘an art form that combines visual and verbal narratives in a book format. A true picturebook tells the story both with words and illustrations. Sometimes they work together, sometimes separately’ (Evans, 2011: 54). David Lewis indicated that:

The words tell you something and the pictures show you something; the two things may be more or less related, but they may not. Back and forth you must go, wielding two kinds of looking that you must learn to fuse into understanding.

Lewis (2009: xii)

Seeing a picturebook as an art object is something that Barbara Bader noted in her well-used definition from 40 years ago:

A picturebook is text, illustrations, total design; an item of manufacture and a commercial product; a social, cultural, historical document; and foremost an experience for a child. As an art form it hinges on the interdependence of pictures and words, on the simultaneous display of two facing pages, and on the drama of the turning page.

Bader (1976: 1)

Whilst accepting these definitions, there is increasingly a blurring of the boundaries, an overlapping and meshing of characteristics normally associated with comics and graphic novels with those associated with picturebooks. Philip Nel stated: ‘The text–image relationship in a picture book is typically less complex than it is in a comic book’ (2012: 447). Nodelman agreed that ‘in terms of structure comics are more complicated than picture books’ (2012: 437). Natalie op de Beeck (2012) noted that picturebooks have quite a few things in common with graphic novels; she stated that they are ‘graphic narratives that operate in a medium called comics’ (2012: 468). Despite this merging of characteristics and an awareness that although there are differences between the two genres there are also many similarities, there are still more studies of picturebooks than of comics and graphic novels. A group of scholars interested in this seeming dichotomy between the genres considered ‘Why Comics Are and Are Not Picture Books’. They questioned why comics should be studied alongside picturebooks, and why it is still difficult to do so. Hatfield and Svonkin, members of this group, noted that despite sharing many similarities there are:

different ideological frameworks: picture books are generally seen as empowering young readers to take part in a social structure that prizes official literacy, while comics, in contrast, are often seen as fugitive reading competing with or even obstructing that literacy.

Hatfield & Svonkin (2012: 431)

Things are changing!

A new breed of visual text is emerging, the fusion text.

It is a ‘new kid on the block’, one that is presenting challenging, thought-provoking and sometimes controversial reading material in creative, artistic forms.

At first glance fusion texts may not look very different; however, if one looks closely they are an amalgam of features from other genres – comics, graphic novels, illustrated books and picturebooks – and they draw on differing illustrative techniques to create the visual aspect of the text. Fusion texts are not just different because of the way they look; the subject matter too has its part to play. The visual artistry of fusion texts fuses, links and coalesces with the subject matter, which in itself is often challenging, problematic and thought-provoking. It seems that this kind of content is ‘crying out’ to be illustrated in a less traditional manner – in a way that merges differing genres with different illustrative techniques, such as, drawing, painting, photography, collage, photomontage, computer-generated imagery and sculpture. The art of the fusion text exhibits a unique and distinctly bold approach and the creator has been influenced by specific, often personal and emotional, experiences that have shaped their artistic vision.

Although the fusion text is a fairly new phenomenon, its precursor was starting to emerge over 30 years ago when Eisner noted: ‘comic book and strip artists have been developing in their craft the interplay of words and images. They have in the process, I believe, achieved a successful cross breeding of illustration and prose’ (1985: 2). It is this cross breeding of different, creative forms of illustration and prose that is one of the key features of fusion texts and Eisner went on to say:

The format of comics presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretative skills.... The reading of a graphic novel is an act of both aesthetic perception and intellectual pursuit.

Eisner (1985: 2)

It is this act of aesthetic perception and intellectual pursuit when reading a graphic novel that is also required when reading a fusion text, as this usually displays a high degree of creativity and innovation and isn’t always easy to understand at first glance. Fusion texts necessitate that the reader gives both time and effort to ensure that they are fully appreciated. Indeed many fusion texts are similar to postmodern picturebooks, which often present the reader with multiple reading pathways and which are challenging to read because of their non-linear texts and their lack of a straightforward text topology; authors play with what is real and what isn’t and there are numerous perspectives in terms of voice, illustrations and content (Pantaleo, 2009; Serafini, 2005; Sipe & Pantaleo, 2008).

This playing with what is and isn’t real is not easy and creators of fusion texts sometime struggle with how to verbalise the creation of these texts. In talking about his search for story in his wordless graphic novel/picturebook, The Arrival, which is a fusion of differing styles and techniques, Shaun Tan verbalised his concerns stating:

In particular, one question that I think about every day as an artist: how can I successfully combine written narrative and visual artwork in a way that’s unique. What can an illustrated story do that other stories can’t and how can it access a world that is otherwise inaccessible?

Tan (2011: 3)

Tan further shared his thoughts:

certain ideas demand to be expressed in certain ways, a conclusion I come to again and again as a reader, critic, writer and artist and no doubt a principle that drives so many artists and writers to constant experimentation, trying to give a tangible name and shape to ideas that might otherwise seem vague or nebulous. Something unique often emerges from that struggle.

Tan (2011: 4)

Tan went on to note how difficult it is to find the exact way of representing what one is doing:

When I look at the work of other creators, I always see beyond the page surface and imagine them struggling the way I do: trawling through many different fragments of drawing and writing and discovering that some compositions work – seem truthful, precise, and evocative while others appear false, inarticulate, or disjointed. After a while, every artist comes to realise that they are not just expressing an idea, they are engineering a personal language, tailored to suit that idea. For an illustrator, it’s a language that involves image, text, page layout, typography, physical format, and media, all the things that work together in a complex grammar of their own, and open to constant reinvention. And this is something that almost defies the graphic novel – an experimentation, playfulness, even irreverence, when it comes to rules of form and style.

Tan (2011: 5)

Other writers are attempting to describe this rapidly emerging cross-breed text. Panaou and Michaelides (2011) call them ‘hybrid’ texts, whilst Foster (2011), in comparing graphic novels with picturebooks, feels that ‘graphic novel’ is a slippery term to define. In his research he claims they are ‘morphed’ texts. This fusion, morphing or hybridising of features relates to the artistic techniques being used as well as to the use of the comic strip/graphic novel features being incorporated. In a search to find answers to why comics are and are not picture books, Hatfield and Svonkin, stated that by ‘smashing together two similar yet culturally distinct genres, picture books and comics, we can spark a discussion that will offer new ways of thinking about the distinctions among genres, forms and modes’ (2012: 432). This ‘smashing together’ of genres can be seen as being analogous to fusing the differing genres. Hatfield and Svonkin drew on Eisenstein’s theories of dialectical montage in cinema stating meaning was created in montage ‘by violently smashing image against image, so that images juxtaposed in opposition to each other create a new dialectical meaning each image separately could never evoke’ (2012: 432). The fusion text is such a juxtaposition.

Increasing numbers of author/illustrators now create fusion texts, with Shaun Tan, Peter Sis, Matt Ottley and Dave McKean being some of the forerunners. Many of Tan’s picturebooks cross the boundary into fusion texts and it is his book The Lost Thing (2000) that springs to mind immediately, incorporating as it does story boxes, overlapping drawn images, speech bubbles, captions and collage.

Many fusion author/illustrators have won awards for their thought-provoking, challenging texts:

All of these award-winning books show the different perspectives and characteristics of fusion texts, texts that can be challenging to read and understand and that require readers to commit energy, effort and time to read and to make sense of them. It is, however, to the work of Dave McKean that I again turn. His work is the epitome of the fusion text.

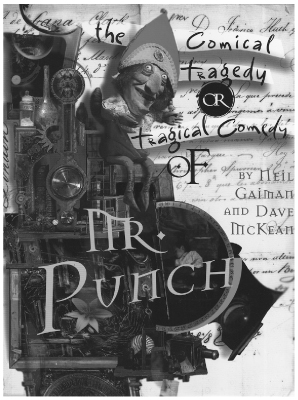

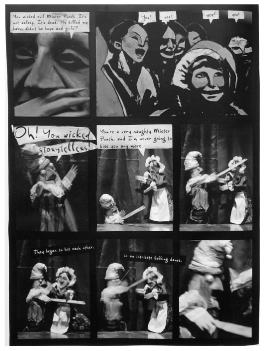

British born McKean is an artistic all-rounder (although he states that he is not an artist) and a true iconoclast. His work blends and mixes aspects of drawing, painting, photography, collage, found objects, sculpture, and computer-generated digital art for a fusion text experience unlike any other. His work was showing many of the features of the fusion text over 20 years ago but over time his style has changed, morphing into a dynamic, constantly changing style that now fuses all manner of different techniques in any one text. In his early artistic career he illustrated comics and graphic novels and was famous for his work on all the covers of Neil Gaiman’s celebrated Sandman series. His first collaboration with Neil Gaiman was Violent Cases (1987), a short graphic novel portraying disturbing childhood memories. These themes of early childhood perception and the nature of memory were visited again in The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch (2006) (Figure 5.5) (Plate 22).

This story of childhood innocence and adult pain tells of a young boy, who, whilst in his grandfather’s failing seaside arcade, encounters a mysterious Punch and Judy man with a dark past, and a woman who makes her living playing a mermaid. As their lives intertwine and their stories unfold, the boy is forced to confront family secrets, strange puppets and a nightmarish world of violence and betrayal.

Gaiman’s story of Mr. Punch is dark, challenging and disturbing. His text and McKean’s visual images are a fusion of differing techniques which play with the passage of time and fuse to create a compelling and unsettling whole. Even the cover is unsettling and the reader knows from previous knowledge of Punch and Judy shows that violent Punch eventually kills all the other characters:

Figure 5.5 (Plate 22) The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean (2006).

He threw the baby out of the window. Then he battered his wife to death. He killed a policeman who came to arrest him. He caused the hangman to be hanged in his place. He murdered a ghost. And outwitted the devil himself. He never died.

(Back cover synopsis) (Figures 5.6, 5.7, 5.8 (Plate 23) and 5.9)

In considering Mr. Punch, Paul Gravett (2005), comic and graphic novel researcher, noted that from a boy’s perspective, adults loom as ‘threatening creatures’, seething with the sort of violence against the family that Mr. Punch gets away with. McKean deliberately confounds readers’ expectations, by enacting some of the disturbingly ‘real’ everyday scenes with puppet-like figures and sets, in contrast to the ‘unreal’ dreaming and remembering recorded in photographs.

In Pictures That Tick (2009), McKean collected a variety of short comics stories from the 1990s and 2000s. As with Mr. Punch, the content of each story is dark and challenging and leaves the reader/viewer feeling uneasy as they ponder the stories’ meanings. Gathered together they represent a tour-de-force achievement and the whole fusion text stretches the boundaries of comics art. Each story is

Figure 5.6 The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch: He threw the baby out of the window.

Figure 5.7 The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch: He battered his wife to death.

Figure 5.8 (Plate 23) The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch: He caused the hangman to be hanged.

Figure 5.9 The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch: He outwitted the devil.

written and illustrated in different ways many of them being made up of separate images fused together as a whole (Figure 5.10). As a ‘picturebook guy’ studying comics, Perry Nodelman commented that in comics ‘words appear not only outside of and near pictures, but also within pictures, superimposed over images (often already busy ones), or in the speech balloons that interrupt the pictorial space depicted while implying that it continues on behind them’ (2012: 437). He goes on to note that ‘comics is a “mosaic art”: in which lots of separate little pieces that come together through their relationships to each other form a whole, but nevertheless remain apparent as still-separate pieces’ (2012: 438). Much of McKean’s work exhibits this ‘mosaic art’ but is always much more.

Panaou and Michaelides note that McKean’s work ‘breaks conventions, resists categorisation, subverts reading expectations, and yet is highly successful in communicating powerful and engaging stories’ (2011: 63). They also state, ‘McKean’s techniques take the reader on a journey between imagination and reality: drawings and paintings (fictional part), photos (the real part), collages and graphics (somewhere in between)’ (2011: 65).

McKean is a real fusion text artist but in conjunction with inspirational authors his creations are legendary. Some of his most interesting fusion texts are aimed at a child audience and are those combining his artistic and creative talents with different authors.

Almond and McKean worked together on a set of three books all dealing with complex, disturbing issues. In the first Almond writes about bereavement and bullying. The Savage (2008) is a ‘fusion’ book which is part picturebook, part illustrated story book, and part graphic novel. The second book, Slog’s Dad (2010) is also about the loss of a father; this time the reader hears how Slog, the young boy deals with his grief, believing as he does that his dad has come back from the dead. Mouse, Bird, Snake, Wolf (2013), the third of this Almond/McKean collaboration, deals with the story of the creation. It is a complex tale about the inevitability of evil (personified by a wolf), the corruptive nature of power (as portrayed by the gods), and the existence of hope and faith as portrayed through the eyes of Ben, the youngest of the three mortal characters. It is an unsettling, disturbing story that leaves lasting and troubling thoughts in one’s mind.

In reviewing Mouse, Bird, Snake, Wolf, Jones felt there was something very special in McKean’s artwork:

There’s a Dali-esque feel to some of his panels, that sort of blurring of reality and imagination, colours burning, images merging, and slightly too long limbs that don’t feel grotesque but feel somehow balletic and graceful. He’s very painterly in this, and it’s something quite special. I loved his ‘transformation’ scenes where the children imagine the new things. The children ‘look inside’ themselves, and the images come from a dark part of their thoughts and are borne to life through the power of their imagination. The wolf panel itself is a genuinely unnerving moment and it’s worthwhile, if you’re sharing this or recommending it to younger readers, to take a second and look at this moment yourself.

Jones (2013)

It is McKean’s work with Neil Gaiman that exhibits fusion text characteristics most effectively. Together they create emotionally complex fusion texts that oblige the reader to tolerate ambiguity and incongruity breaking into the traditional text. They frequently disrupt previously accepted norms in terms of layout, presenting picture and text surprises from very different perspectives. In addition, the stories often hold multiple meanings that provoke, tease and cajole the reader in different ways as they read.

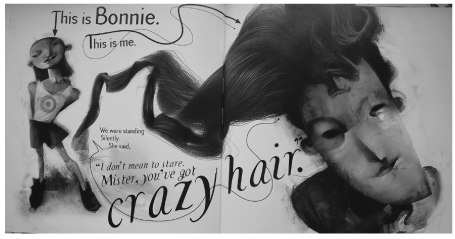

The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish (1997), The Wolves in the Wall (2003) and award-winning Crazy Hair (2009) are three books created by the ingenious liaison of these two experts. They are true fusion texts in terms of their narratives and the illustrative art styles they draw on.

In the first, a little boy swaps his dad for his best friend’s goldfish (Figure 5.11). When his mum finds out, he has to get dad back but that is when the trouble starts as dad has been swapped all over town and getting him back is not easy.

In describing the book, Panaou and Michaelides state:

The pages oscillate between genres. Panels and balloons are overused on one page and not used at all on the next. There is a continuous fluctuation of the text–image interaction and expressive mannerisms. The book combines forms and elements from different genres, all at the same time and sometimes on the same page. There is no specific pattern, but rather a constant change and blending. The only limitation is the story; anything that contribute to the narration of a good story is permissible, anything that enlists the different strengths of images and words and overcomes their individual inadequacies. Thus, text and illustrations break every rule forming a hybrid (fusion) picturebook, comic book, illustrated book, graphic novel.

Panaou & Michaelides (2011: 65)

In The Wolves in the Walls, Gaiman’s enigmatic and in places disturbing narrative is perfectly complemented by McKean’s artwork; their work fuses to create an amazing whole (see Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.3 (Plate 21)).

The third book, Crazy Hair is a visually stunning and captivating tale of Bonnie, and the little girl’s fascination with Mister’s unbelievably amazing hair. The text and images fuse to create a visually stunning and captivating book, which repeatedly draws the reader back to inspect the hyperreal illustrations (Garrett, 2013), and admire the links between words and pictures (Figure 5.12) (Plate 24).

All three texts exhibit the creators’ truly creative and imaginative fusion style. They are oddly humorous, rather unsettling and yet intriguing at the same time. They invite the reader to return repeatedly to search for and discover new features in both the text and images.

Figure 5.12 (Plate 24) Crazy Hair: This is Bonnie. This is me.

In looking at McKean’s artistic style, Panaou and Michaelides considered the way his books ‘are constructed through a powerful fusion of generic conventions, a combination that prompts the reader to stay constantly alert, assessing the nature of word–image interaction on each page, and switching from one mode of interaction to another’ (2011: 66). They go on to say:

While these ‘hybrids’ certainly do imply an experienced reader – one who is familiar with the conventions of each of the enlisted genres – they also imply a reader who, being a child of the post-modern era, accepts and celebrates flexibility, fluidity, and transmutation.

Panaou & Michaelides (2011:66)

It isn’t always easy to define and categorise visual texts when a totally new and different genre appears. Some readers are content that they exist whilst others want the texts to be defined and classified, maybe by their aesthetic qualities, implied audience, subject matter and/or style. Some may feel it isn’t important to give these visually different books a name. However, I feel it is, and in addition I feel it is important to celebrate this new kind of text that is challenging by its visual non-conformity.

Ironically, good narrative illustration is not about ‘illustration’ at all, in the sense of visual clarity, definition, or empirical observation. It’s all about uncertainty, open-mindedness, slipperiness, and even vagueness. There’s a tacit recognition in much graphic fiction that some things cannot be adequately expressed through words: an idea might be just so unfamiliar, an emotion so ambivalent, a concept so nameless that is best represented either wordlessly, through a visual subversion of words, or as an expansion of their meaning using careful juxtaposition.

Tan (2011:8)

... and by careful fusion!

The fusion text is here to stay and, if accomplished author/illustrators continue to produce quality visual texts like the ones considered here, then it will not be long before comics, graphic novels and picturebooks will, along with the rapidly developing and closely related, fusion texts, be seen as respectable genres, read, enjoyed and talked about by many.

Arnold, A. (2003) The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary. Time Magazine, 14 November 2003.

Bader, B. (1976) American Picture Books: From Noah’s Ark to the Beast within. New York: Macmillan.

Briggs, R. (2008) in conversation with Rachael Cooke. Big kid, ‘old git’ and still in the rudest of health. The Guardian, 10 August 2008. www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/aug/10/booksforchildrenandteenagers (accessed 23 February 2010).

Couch, C. (2000) The Publication and Format of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon, Image & Narratology, December. www.imageandnarrative.be/narratology/narratology.htm (accessed 24 February 2009).

de Vos, G. (2005) ABC’s of graphic novels, Resource Links, 10(3): 1–8.

Eco, U. (1986) Faith in Fakes: Travels in Hyperreality. London: Vintage.

Eisner, W. (1985) Comics and Sequential Art. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press.

Evans, J. (ed.) (1998) What’s in the Picture? Responding to Illustrations in Picture Books. London: Paul Chapman.

Evans, J. (ed.) (2009) Talking Beyond the Page: Reading and Responding to Picturebooks. London: Routledge.

Evans, J. (2011) Raymond Briggs: Controversially Blurring Boundaries, Bookbird, 49(4): 49–61.

Foster, J. (2011) Picture Books as Graphic Novels and Vice Versa: The Australian Experience, Bookbird, 49(4): 68–75.

Garrett, J. (2013) Realism, Surrealism, and Hyperrealism in American Children’s Book Illustration, in Grilli, G. (ed.) Bologna: Fifty Years of Children’s Books from around the World. Bologna: Bologna University Press, pp. 147–158.

Gibson, M. (2008) ‘So What Is This Mango, Anyway’: Understanding Manga, Comics and Graphic Novels, NATE Classroom, 5(Summer): 8–10.

Gravett, P. (2005) Graphic Novels: Stories to Change Your Life. London: Aurum Press.

Hatfield, C. & Svonkin, C. (2012) Why Comics Are and Are Not Picture Books: Introduction, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(4): 429–435.

Jones, N. (2013) Mouse Bird Snake Wolf: David Almond & Dave McKean, Book Review. http://didyoueverstoptothink.wordpress.com/2013/06/07/mouse-bird-snake-wolf/

Joseph, M. (2012) Seeing the Visible Book: How Graphic Novels Resist Reading, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(4): 454–467.

Lewis, D. (2009) Foreword, in Evans, J. (ed.) Talking Beyond the Page: Reading and Responding to Picturebooks. London: Routledge, pp. xii–,xiii.

Lim, Y. (2011) Educational Graphic Novels: Korean Children’s Favorite Now, Bookbird, 49(4): 40–48.

McCloud, S. (1994) Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins.

Martin, M. (2009) How Comic Books Became Part of the Literary Establishment, The Telegraph, 2 April 2009.

Nel, P. (2012) Same Genus, Different Species? Comics and Picture Books, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(4): 445–453.

Nodelman, P. (2012) Picture Book Guy Looks at Comics: Structural Differences in Two Kinds of Visual Narrative, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(4): 436–444.

op de Beeck, N. (2012) On Comics-Style Picture Books and Picture-Bookish Comics, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(4): 468–476.

Panaou, P. & Michaelides, F. (2011) Dave McKean’s Art: Transcending Limitations of the Graphic Novel Genre, Bookbird, 49(4): 62–67.

Pantaleo, S. (2009) Exploring Children’s Responses to the Postmodern Picturebook, Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book? In Evans, J. (ed.) Talking Beyond the Page: Reading and Responding to Picturebooks. London: Routledge, pp. 44–61.

Pullman, P. (1995) Partners in a Dance, Books for Keeps, 92(May): 18–21.

Serafini, F. (2005) Voices in the Park, Voices in the Classroom: Readers responding to Postmodern Picturebooks, Reading, Research and Instruction, 44(3): 47–64.

Sipe, L. & Pantaleo, S. (2008) Postmodern Picturebooks: Play, Parody and Self-Referentiality. New York: Routledge.

Tan, S. (2011) The Accidental Graphic Novelist, Bookbird, 49(4): 1–9.

Tarhandeh, S. (2011) Striving to Survive: Comic Strips in Iran, Bookbird, 49(4): 24–31.

Weiner, S. (2001) The I01 Best Graphic Novels. New York: NBM Publishing.

Wroe, N. (2004) Bloomin’ Christmas, The Guardian, 18 December 2004. www.guardian.co.uk/books/2004/dec/18/featuresreviews.guardianreview8 (accessed 24 February 2010).

Almond, D. & McKean, D. (2008) The Savage. London: Walker Books.

Almond, D. & McKean, D. (2010) Slog’s Dad. London: Walker Books.

Almond, D. & McKean, D. (2013) Mouse, Bird, Snake, Wolf. London: Walker Books.

Briggs, R. (1982) When the Wind Blows. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Briggs, R. (2008) Gentleman Jim. London: Jonathan Cape.

Eisner, W. (1978) A Contract with God. New York: Baronet Press Books.

Fairfield, L. (2011) Tyranny: I Keep You Thin. London: Walker Books.

Gaiman, N. & McKean, D. (1987) Violent Cases. London: Escape Books.

Gaiman, N. & McKean, D. (1997) The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish. New York: HarperCollins.

Gaiman, N. & McKean, D. (2003) The Wolves in the Wall. New York: HarperCollins.

Gaiman, N. & McKean, D. (2006) The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch.London: Bloomsbury.

Gaiman, N. & McKean, D. (2009) Crazy Hair. New York: HarperCollins.

McKean, D. (2009) Pictures That Tick. Milwaukee, WI: Dark Horse Books.

Marsden, J., illus. Ottley, M. (2008) Home and Away. Melbourne: Lothian Children’s Books.

Ottley, M. (2007) Requiem for a Beast: A Work for Image, Word and Music. Melbourne: Lothian Publishers.

Reviati, D. (2009) Morti di Sonno. Bologna: Coconino Press.

Satrapi, M. (2003) Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood. London: Pantheon.

Selznick, B. (2007) The Invention of Hugo Cabret. London: Scholastic.

Sis, P. (2007) The Wall: Growing up behind the Iron Curtain. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spiegelman, A. (1973) Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. New York: Pantheon.

Tamaki, M. & Tamaki, J. (2008) Skim. London: Walker Books.

Tan, S. (2000) The Lost Thing. Melbourne: Lothian Publishers.

Tan, S. (2006) The Arrival. Melbourne: Lothian Publishers.