How visual explorations shape the young readers’ taste

Marnie Campagnaro

There are two ways in which a text may be illustrated: an artist can use a literal, descriptive, denotative mode, or a symbolic, implied, connotative mode. In the denotative mode, an artist’s illustrations are a direct and literal imitation of the ‘text’ reality, whilst in the connotative mode, ideas and concepts are not directly signified but are implied by the associations or meanings that are suggested or evoked. In this latter mode the artist uses metaphors and similes to illustrate a text, thus introducing additional meaning and requiring that readers must draw on previous experiences in order to interpret and draw meaning from the text. This chapter will look at young readers’ responses to a selection of picturebooks using these two types of illustrative styles. It focuses in particular on Capitan Omicidio (Captain Murderer), a version of Charles Perrault’s Blue Beard written by Charles Dickens and illustrated by Fabian Negrin.

There is evidence that a ‘quiet revolution’ (Arizpe & Styles, 2003) has been happening in children’s literature over the last 20 years. Increasingly, newer editions of picturebooks have combined written aspects of older texts with contemporary and often controversial visual styles to create new picturebooks which are outstanding works of art.

Picturebooks are a valuable educational resource which encourage children’s aesthetic awareness and several critical researchers have recently focused on the educational and aesthetic value of picturebooks (Colomer, Kümmerling-Meibauer & Silva-Díaz, 2010; Hamelin, 2012; Salisbury & Styles, 2012; Campagnaro & Dallari, 2013). Moreover, many qualitative researches have investigated the way children interact with picturebooks in primary and secondary school (Arizpe & Styles, 2003; Pantaleo, 2008; Sipe & Pantaleo, 2008; Evans, 2009; Arizpe, Colomer & Martínez-Roldán, 2014). These studies show that visual narration creates a shared space which affords the possibility of discussion with children and can thereby stimulate a deeper understanding of the fictional universe and the real world. In addition, they demonstrate that the visual and aesthetic literacy of a child can be developed through the reading of picturebooks.

Two visual modes of representation: the child’s engagement in literal and symbolic visual narratives

Despite there being many ways in which a text can be illustrated, a visual artist can basically use two visual modes of representation: a literal, descriptive mode, or a symbolic, implied mode. In the first mode the artist illustrates the text using images which are a direct imitation of the ‘text’ reality, while in the second mode the artist uses metaphors and similes to illustrate the text, thereby introducing additional but implied meaning.

These two modalities recall the distinction between denotation and connotation described by Roland Barthes in his influential book, Image, Music, Text (1977 [1964]). According to Barthes, denotation is what a sign (or text) describes; at a first level of meaning, the ‘literal or obvious meaning’. Connotation is a second level of meaning, the additional cultural meanings we can find in the image or text, including emotional associations that a sign carries.

Picturebooks can likewise be marked by these same two modes of representation: a visual denotative language (something that is signified directly or literally), or a visual connotative language (something that is not signified directly or literally but which is implied). Visual denotative picturebooks are characterized by illustrations making explicit references to the text. In these picturebooks, the pictures convey the conventional and primary meaning of the text and make it clear and explicit. The conveyed meaning is precise and unequivocal. Conversely, visual connotative picturebooks are characterized by illustrations making only implicit reference to the texts. In such picturebooks the pictures do not directly represent the text but rather fill in the textual gaps which may emerge from an interpretational reading of the text. Such picturebooks may provoke an emotional impact in the reader. The text–image relation in such picturebooks will frequently have a high degree of ambiguity. Ambiguity is an important aesthetic quality because it provides the reader with multiple opportunities to access and interpret the meaning of the story.

Pointing out the differences between visual denotative and visual connotative picturebooks is crucial because visual language affects our meaning-making process and enhances our perception of the story. For instance, visual denotative language helps children to understand the meaning of some situations or concepts, but often has little or no aesthetic potential (Schwarcz, 1982: 50). In contrast, the visual connotative language has an aesthetic potential: it engages a child’s imagination and often gives ‘an open invitation to the child to experience some empathy with the author’ (Schwarcz, 1982: 51).

‘To see is to interpret’: the potential of visual texts

According to Schwarcz (1982), illustrating a text is ‘a matter of interpreting and commenting on it. Coming upon a metaphor in a text he is about to illustrate, the artist has a wide range of possibilities; he chooses contents and meanings and transfers them to his pictures’ (1982: 34).

This process can be analysed using the definition Gombrich gave in relation to the visual representation in his most influential book, Art and Illusion: ‘to see is to interpret’ (Gombrich, 2002: XIII [1960]). Gombrich’s constructivist theory of perception reminds us that reading and commenting on an image is always a process based on the relativity of our vision. Our cultural, social and psychological history shapes our perception and representations of reality. For Gombrich, there is no such thing as an ‘innocent look’; when we perceive an image and understand it, we have been influenced by our knowledge of the world.

If we look at ambiguous and controversial images in connotative texts, the feeling of disorientation and amazement that often arises can make the act of seeing even more lively and engaging. This is evident when looking at the ambiguous and challenging book Imagine by the English illustrator Norman Messenger (Messenger, 2005), which has illustrations of a bucolic landscape with hills, mountains, groves, pastures, glades, houses, castles and Roman ruins. On looking more carefully at these images the reader discovers a strange new world: the idyllic landscape stunningly hides behind giant faces on the hill sides!

Young readers’ aesthetic explorations of ambiguous and controversial picturebooks

According to Gadamer’s hermeneutics, aesthetics have a crucial role to play in life experience (Gadamer, 1986). Aesthetic investigation is vital because it disrupts and challenges a reader’s customary expectations of a text; it also pushes the reader towards an aesthetic attentiveness that says something essential about the experience an individual has of the text.

For Gadamer, artwork is interrogative by nature and since the meaning transmitted can never be fully understood in the same way by all, it remains partly enigmatic and the reader’s hermeneutic, interpretative involvement is required. Disclosure and hiddenness are not contraries in Gadamer’s aesthetics, but mutually dependent: the disclosed reveals the presence of the undisclosed in the disclosed (Davey, 2011).

Using this hermeneutic, interpretative perspective, controversial picturebooks become valuable aesthetical tools. Ambiguities and discrepancies in a controversial picturebook have a fundamental role to play because they require the reader to become involved in interpreting a text and they help him/her to orientate his/her own meaning-making process. Understanding a plot in a picturebook is much more than the simple understanding of a sequence of sentences. It calls for far more complex abilities than just a good command of the language or good reading and writing skills; it requires children to establish a relationship between ambiguous details in a single illustration and ambiguous details in sequences of illustrations. In order to establish a relationship between characters, environments, purposes, actions and unexpected events and to grasp the content of a story, the reader has to give a meaning to ambiguities and discrepancies in a plot, to understand metaphors and to formulate hypotheses. Since the first reading of a picturebook doesn’t always lead to the ‘authentic’ reading of the story, drawing on all of these actions is fundamental for understanding to take place.

During the reading, children have to become familiar with the existence of multiple reading levels in a story. In order to clarify this process, I will describe the picturebook reading process of a child attending primary school:

- First, the child recognizes, mentions and enumerates the characters, objects and setting of the story.

- Second, the child notices the relationships existing within a single picture in relation to other pictures and discovers some details that at first sight might have appeared ‘meaningless’.

- Third, the child analyses these details and realizes that a deeper reading level is required. At this point, the child formulates a hypothesis to interpret the ‘hidden’ narrative plot, posing questions in relation to the ambiguous and apparently meaningless details of the story.

Due to the reader’s interpretive involvement, the undisclosed meaning of a plot (that is, what has not explicitly been said or seen) may be disclosed, giving the child access to the ‘authentic’ pleasure and understanding of the story.

Visual explorations and young readers’ taste: an observational research

The theoretical perspective I have just outlined was put into practice in an observational research project I carried out in an Italian primary school in 2010. In this qualitative study, observation was used as the investigation methodology. The aim of the study was to explore children’s response to the two visual modes of representation in picturebooks (that is, visual denotative language and visual connotative language) through the reading of three popular fairy tales illustrated by different artists.

The study was inspired by some well-known critical studies carried out by scholars such as Schwarcz (1982), focusing on Cinderella, Nodelman (1988), focusing on Snow White, and Nikolajeva and Scott (2006), focusing on Thumbelina. These studies investigated the relationship between words and pictures in the three fairy tale picturebooks, but they did not discuss children’s responses as this study aims to do.

Even though I was aware of the methodological difficulties in drawing demarcation lines and in applying categorization methods to fairy tale picturebooks, I planned a research project that would enable me to observe and encourage ‘aesthetical development’ in young readers. The children started by reading the fairy tales which used explicit denotative visual language (the favourite visual language chosen by the majority of children at the beginning of the research). They were then asked to compare these ‘unambiguous’ illustrated stories with other more controversial versions which used more connotative visual language. Finally, the children were asked to state their preferences.

My aim in conducting this qualitative study was to consider:

- How children respond to fairy tale picturebooks marked by different modes of representation.

- Their mode of choice and the preference they express for either a visual denotative language, marked by a literal and descriptive referentiality to the text, or a visual connotative language, marked by a high degree of ambiguity and aesthetic potential.

- How the explicit teaching of visual exploration shapes a young reader’s taste.

The structure of the observational research

The research methodology employed was developed drawing upon some valuable guidelines from a previous survey conducted on a world scale using the Delphi technique (Linstone & Turoff, 1975): a research method conducted by an expert panel of 28 experts that included scholars, publishers and illustrators from all over the world who, in this survey, had dealt with some multidimensional aspects of picturebooks (Campagnaro, 2012).

My observational study involved children aged 6, 8 and 10 and was carried out in a primary school in the Padua district of Northern Italy. It had an observation group of 62 children (52 children with Italian citizenship and 10 with foreign citizenship). The observation group was divided into three subgroups, according to their school classes: the first class consisted of 20 children aged 6 (11 girls and 9 boys); the second class consisted of a group of 17 children aged 8 (9 girls and 8 boys); and the third class consisted of a group of 25 children aged 10 (11 girls and 14 boys). I chose children aged 6, 8 and 10 from the different age groups in order to present a multifaceted children’s response study based on children’s cognitive and aesthetical development at different ages.

During the research I observed the modes of interaction expressed by children in relation to 21 versions of illustrated fairy tales: 7 different illustrated versions of Little Red Riding Hood, 7 of Hansel and Gretel, and 7 of Bluebeard.

Three factors were taken into consideration when selecting the fairy tale picturebooks.

- First, the selection needed to offer an important outlook on the richness and the variety of contemporary picturebooks: the goal was to promote a greater awareness both in children and teachers about the mentioned ‘quiet revolution’ (Arizpe & Styles, 2003) that has involved children’s literature in recent years.

- Second, the selection needed to include fairy tale picturebooks that had been positively reviewed or whose author/illustrators had received prominent children’s literary awards.

- Third, the selection needed to be equally representative of the two different visual categories.

The 21 fairy tale picturebooks were grouped into two families: 11 illustrated fairy tales marked by a denotative, explicit, visual language and 10 fairy tales marked by a connotative, less explicit, visual language.

I decided to apply the ‘denotative–connotative’ categorization used for picturebooks to the illustrated fairy tales because these two fields share a great number of elements. The fairy tale is an open and ductile text, which can lend itself to multiple reinterpretations: the original texts, any text innovations or rewritings of the classic fairy tale, together with the contextual genesis of a specific iconic representation and a particular graphic project, give rise to a work which is significantly close to the concept of a picturebook. Some of the works used in this study are characterized by a relationship in which text and pictures are inextricably bound to each other: the text denotes the fairy tale, but the connotation is made possible by the pictures, which give the text an added value.

In the fairy tales illustrated according to a denotative visual language, pictures convey the conventional and primary meaning of the text. Undoubtedly, there are notable differences between these books: in some of them, the visual narration amplifies the text and may sometimes encourage the reader to take part in the plot from an emotional point of view, but the visual language of all these books nevertheless shows a strong adherence to the text; it depicts a faithful portrait of the textual reality. Table 6.1 shows the list of the fairy tale picturebooks using denotative visual language:

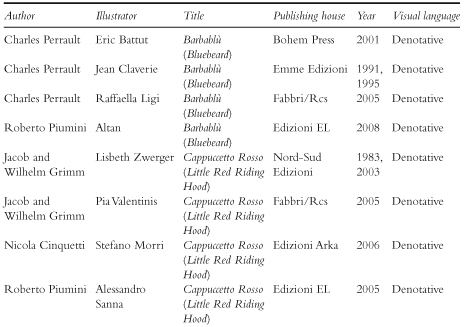

Table 6.1 Fairy tale picturebooks using denotative visual language

Conversely, the illustrations from the fairy tale picturebooks characterized by a visual connotative language, add ‘something’ to the text through the use of uncommon graphic and artistic codes; for example, experimentation with unusual perspective and composition and the wise use of symbols and visual metaphors. These texts instil a sense of wonder, curiosity and emotional tension and propel the reader towards a more aesthetically aware state. For instance, they allow readers to associate different meanings/perspectives with the reading of the same narrative sequences. Table 6.2 shows the fairy tale picturebooks using connotative visual language:

Table 6.2 Fairy tale picturebooks using connotative visual language

The phases of the observational research

The observational research was divided into two phases. The first phase lasted 5 weeks (4 days a week, 5 hours a day). In the first week the main goals, the path and the children’s role in the research were shared with the parents and their children. In the second week, I presented and read two picturebooks in each classroom, Piccolo blu e piccolo giallo (Little Blue and Little Yellow) by Leo Lionni and Dentro me (In Me) by Alex Cousseau and Kitty Crowther to get the children familiar with different types of visual narration (abstract and symbolic language) and with the disclosed and undisclosed elements of the picturebooks (such as details on the cover, on the endpapers, on the title page, etc.). These first two weeks were also very important in creating space and opportunity for discussion with the children.

I then started the observational research with the fairy tale picturebooks. Each week I presented a different fairy tale: initially Little Red Riding Hood, then Hansel and Gretel, and finally Bluebeard in the third week. I followed the same sequence each time I introduced a new fairy tale picturebook to the children: first, I presented the title, authors, illustrators and publishing house, front cover, endpapers, colophon (at the beginning or at the end of the book) and title page, then I began reading aloud (I read the first two pages of the text, then I showed children the pages I had just read so that they could see the pictures, and continued like this until the end of the picturebook).

After the shared read, the discussion phase started: the children were divided into small groups of no more than 7 or 8 children. Each group was encouraged to read, analyse and compare the seven different versions of each fairy tale, expressing their thoughts and preferences. I personally carried out both the reading phase and the analysis of the books with the children and I allowed time and space for the children’s questions and doubts in relation to the previous reads. During the whole observational research period I was able to rely on the expertise of Alessandra Carraro, a sociologist specializing in ethnography from the University of Padua. She was asked to observe the children’s reactions, to tape their comments with audio and video devices and to write the ethnographic notes.

During this first phase working with the different iconographic versions of the selected works, I examined the ways in which the children communicated with the text and pictures, grasping similarities and differences between the textual and the visual narration, wondering about the metaphorical and challenging illustrations of the selected fairy tales and developing a more consistent aesthetic attentiveness.

The second phase of the research focused on the children borrowing the fairy tale picturebooks to read at home. This lending-activity lasted one month (one day a week during the school timetable). The children were free to choose any of the fairy tales used during the research, take them home to read and to share with their parents. My purpose was clear: to discover which illustrated fairy tales the children were most curious about or liked the most outside the classroom context.

The results of this research were collected through a visual questionnaire completed during three subsequent surveys: the first survey was carried out before the observational research began, the second survey, one month after the first and the third at the end of the research after two months. During the research I also used some typical tools of qualitative research, that is, ethnographic notes, audio-video recordings and reading journals written at home by the children and their parents separately. The parents’ journals were a valuable observational source for the reading and qualitative interpretation of the data.

The findings of the observational research

The children’s responses to the books

First of all, the research highlighted that the children very much enjoyed being actively involved in hermeneutic (interpretational) reading activities. In fact, the analysis of the children’s reading journals revealed that they particularly liked the discussion phase during which they were given opportunities to make comparisons, discover similarities and differences in diverse visual narrative plots, solve challenging ambiguous visual enigmas and experience different aesthetic styles. Huck’s journal entry noted how the books made him curious:

It seemed strange to see these books which didn’t have a lot of differences, but instead there were differences. And how!

These books made me really curious because they had particular pictures which hid something strange. And then in the end in these seven books I noticed these differences in some books. So these seven books really were different one from the other.

Huck (aged 10)

The pleasure of managing interpretive processes was stated even by those children who weren’t keen on books and reading. These children were often fascinated by the dark side of a story like Bluebeard as can be seen in Billy’s journal response:

From the first day we started I liked it straightaway because you read us funny books and scary books like Bluebeard when the wife found the room where he hung his wives who found out about that room and when he was going to kill his wife because she had seen the room as well.

Billy (aged 10)

The research points out that reading and comparing different controversial picturebooks encourages children’s interpretative responses and involvement. It is a challenging activity that could be widely used and promoted at school and undertaken with other subjects or in different contexts. Luce’s journal response shows this kind of involvement:

I would really like to do the project again. It would be nice to read other books about Pinocchio for instance or Puss in Boots. I’d also like to see the pictures in the books we read again.

Luce (aged 8)

In addition to the children’s enjoyment of being involved, the research confirmed the existence of stereotypes in these children’s choices with respect to the visual mode of representation in children’s picturebooks. The existence of such stereotypes is confirmed by the choices the children made during the first observation, at the beginning of the research before they had been offered any aesthetic tools to help read visual texts. In this phase, children chose the picturebooks they preferred exclusively on the basis of a quick reading of the text and pictures, when leafing through the books for the first time.

Most of the children (83.9 per cent) chose those fairy tales in which characters, animals, objects, environment and situations were illustrated in a familiar, unambiguous and explicit way according to the unequivocal ‘realism’ of the visual denotative language. Only 16.1 per cent of them said they preferred a visual connotative language. Strangely, this trend was consolidated in children aged 10. These children appeared to be much more set in their artistic representational ways (90.5 per cent chose the denotative visual mode of representation) than children aged 8 (88.2 per cent) or even 6 (72.3 per cent). In effect children aged 6 were far more willing to choose fairy tale picturebooks with a visual connotative language than the older children: 27.8 per cent of children aged 6, 11.8 per cent of children aged 8 and 9.5 per cent of children aged 10.

Visual cultural conditioning does not wane as the years go by; on the contrary, it grows in older children. If not duly educated, children tend to lose their confidence in dealing with connotative (figurative and symbolic) interpretation (Gardner, 2006 [1983]). In fact the ethnographic notes reported examples in which the 10-year-old children often declared, during the first sessions of the empirical study, that characters, animals, objects, environments and situations have to be easy to identify and pictures should literally explain any narrative passage of the text. They declared that the visual narration has to tell everything and any element that could lead to ambiguity or equivocal interpretive involvement should be removed. For example, the children’s desire to find a clear visual explanation for each narrative passage is evident in the following dialogue with children during the analysis of Grimms’ fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood illustrated by Pia Valentinis (2005):

|

Ben: |

the trees are again bare. |

|

Viviana Group of children: |

but the wolf was alive before! |

|

what’s that got to do with crows? |

|

Laura: |

but how could he die? Pictures don’t answer these questions for a child who doesn’t know the story.... |

Ethnographic notes with 10-year-old children, 4 March 2010

At the beginning of this study, the children tended to avoid ambiguous and controversial picturebooks. They chose picturebooks characterized by explicit, denotative visual language because these books provided them with referentiality and thus reassurance. Nevertheless, as argued earlier, aesthetic investigation should be crucial in children’s experience to disrupt and challenge their customary visual expectations. The data analysis, in fact, pointed out a remarkable change in the preferences expressed by children as the research progressed.

In the second survey, the percentage of children who said they preferred the fairy tales characterized by a connotative visual language rose to 45.9 per cent, while the percentage of children who said they preferred the fairy tales written with a denotative language fell to 54.1 per cent. The increase was particularly significant, as it reached + 29.8 per cent. But the highest peak was reached during the third survey, at the end of the observational research (+ 46 per cent), after the children had borrowed the books shared at school and taken them home.

The opportunity to take home, share and read again the most interesting books changed the initial situation. The children’s new aesthetic attentiveness resulting from their ability to become familiar with challenging visual texts and to share interpretive processes led many of these children (62.1 per cent) to move their preferences towards picturebooks marked by a connotative visual language: John’s journal reflected this change:

I really enjoyed this experience because I found out that book illustrators have their own way of illustrating books, that there are different versions which come from the same story. For example Little Red Riding Hood, or I found out that books can be in black and white and loads of other things...!

John (aged 8)

The children’s preferences

At the end of the research, which fairy tale picturebooks did these children prefer?

Strong and visually challenging fairy tales, with a high aesthetic potential, emotionally pregnant, full of ambiguous and controversial details stimulated the children.

When faced with these kinds of text they asked questions, expressed their doubts, questioned ambiguous pictures. They were very curious and fascinated by dark and provocative narrations.

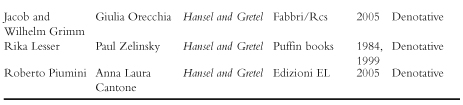

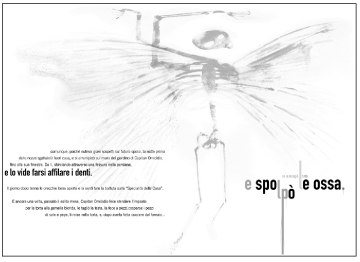

During the reading of Grimms’ Hansel and Gretel illustrated by Lorenzo Mattotti (2009) (Figure 6.1) several 8-year-old children gave their thoughts:

John: it’s a mysterious book but for me also strange because I didn’t expect the pictures to be like that.... I think they are fascinating, they were really good at illustrating it.

Piero: you can see that they were done with a paintbrush.

Penelope: for me the pictures are wonderful but they make me a bit unsure because Hansel looks big.

John: I think they are very... fascinating.

Ethnographic notes with 8-year-old children, 11 March 2010

Figure 6.1 Lorenzo Mattotti’s representation of Hänsel e Gretel (W. & J. Grimm, & L. Mattotti, 2009).

Shaping young readers’ taste in picturebook choices

This research revealed that it is possible to shape a young reader’s taste. The opportunity to read, share, discuss and respond to the picturebooks may support an aesthetic awareness, break some stereotyped visual habits and promote in children a more mature attitude towards reading. Additionally, the pleasure experienced in this hermeneutic involvement may lead children to choose similar picturebooks that can make them think, question and respond, and allow them to relive the same experience. Children from each of the differing age ranges were asked:

Researcher: Out of everything that we have read or looked at what struck or surprised you the most?

That we read so many books, I thought we would read only three books about three stories.

Eric (aged 6), ethnographic notes of 16 March 2010

The stories because I didn’t know that so many Little Red Riding Hoods and Bluebeards existed.

Tyn (aged 8), ethnographic notes of 15 March 2010

When you read Hansel and Gretel with pictures in black and white because I had never seen it before.

Penelope (aged 8), ethnographic notes of 15 March 2010

Showing us so many books like that!

Tom (aged 10), ethnographic notes of 16 March 2010

Reading the books.

David (aged 10), ethnographic notes of 16 March 2010

So many books.

Percy (aged 10), ethnographic notes of 16 March 2010

So many books and pictures.

Goffredo (aged 10), ethnographic notes of 16 March 2010

Challenging children’s curiosity: Captain Murderer, an original Bluebeard

It came as no a surprise that at the end of the research the fairy tale picturebook that best satisfied the children’s curiosities and expectations was Captain Murderer (Capitan Omicidio) by Charles Dickens and Negrin, 2006. After the first read, this picturebook had a very low interest percentage (5.4 per cent), and this was only among children aged 6. Children aged 8 and 10 didn’t show any interest in Captain Murderer. At the end of the research this situation was completely overturned: this fairy tale achieved the highest percentage of preferences among all the fairy tales (21.1 per cent expressed by children aged 6 years, 20 per cent by children aged 8 years and 29.2 per cent by children aged 10 years). It was interesting to point out that this picturebook was of interest to the majority of the children, regardless not only of the age bracket they belonged to but also of their gender.

What was so special about this picturebook? What kind of aesthetical experience does this visual narration offer to young readers?

The classical version of Bluebeard was first written in a literary form by Charles Perrault in 1697. This fairy tale has since been continuously rewritten, adapted and transformed over the course of the intervening centuries and many cultural variations have been produced (Tatar, 2004). Bluebeard is a very appealing ‘tenacious cultural story’ because it produces:

the suspense of all stories in which an enigma about a killer must be solved by one of his potential victims. And by casting the killer as husband and the victim as wife, it adds the ingredients of intimacy, vulnerability, trust, and betrayal to make the story all the more captivating.

Tatar (2004: 14)

This Bluebeardean capacity to grasp the readers’ imagination affected Charles Dickens and references to this persistent folktale ‘recur throughout his works from The Pickwick Papers (1837) to the Mystery of Edwin Drood (1869–70)’ (Barzilai, 2004: 506).

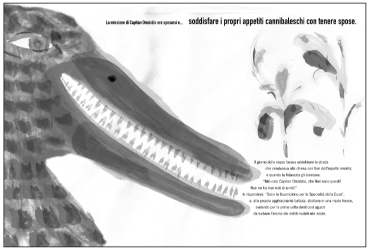

Bluebeard is one of the most blood-curdling fairy tales of the folk tradition. Nevertheless, as Shuli Barzilai (2004) revealed, it did not seem to be blood-curdling enough for Charles Dickens, who, in effect, aimed in his Bluebeard retelling, called Captain Murderer, ‘to draw on a cannibalistic variant of the taly-type [sic] and garnished it, so to speak, with further grisly flourishes’ (Barzilai, 2004: 507). Charles Dickens had known of Captain Murderer since he was a child. A nursemaid, strangely named Mercy, told him hundreds of times in his early youth the story of an ‘off-shoot of the Blue Beard family’: it was this ogre who ‘terrorized the young Dickens over a period of many years’ (Tatar, 2004: 13).

What kind of story is Dickens’ Captain Murderer?

Originally written by Charles Dickens as Nurse’s Stories, in his collection of sketches and reminiscences, The Uncommercial Traveller (1860), Captain Murderer is based on a folktale that brings to mind also the plots of The Robber Bridegroom and Fitcher’s Bird in Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm’s Tales for Young and Old (Kinder- und Hausmärchen), 1857, even if no cannibal elements are present in Grimms’ tales (Barzilai, 2004). It tells the story of Bluebeard, a rich and powerful man who vented his showy cannibalistic tendencies on young women exactly one month after marrying them. These poor women become tasty morsels on his sumptuously laid table. He killed them by chopping off their heads, after which he cut them into small pieces and put them into a pie, whose dough had been prepared in advance by the very same women just before their death. He cooked the pies at the baker’s and then, satisfied, he devoured them, picking even the bones. Marriages and murders followed one after the other in a seemingly unstoppable sequence until a young woman came along who, thirsting for revenge, managed to put an end to Bluebeard’s terrible game.

Dickens’ Captain Murderer is a strong mixture of genres: it belongs ‘to the genre of the comic tale with socially subversive elements’, but also represents ‘a tale of gothic terror in which the desire touch [sic] is a frisson, a shudder or thrill of fear’. It is a ‘comic-macabre story into the mode of carnivalization’ (Barzilai, 2004: 510). Above all, Captain Murderer is a story ‘to be shared in a public arena’ (Barzilai, 2004: 511), as children revealed in their journals:

I really liked Bluebeard because I didn’t know the story and it made me curious because it has something mysterious about it, it’s interesting as well as being wonderful. I really liked the two books called Captain Murderer and Bluebeard.

Suzy’s journal (aged 8)

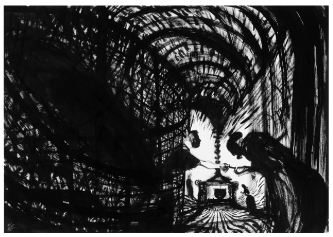

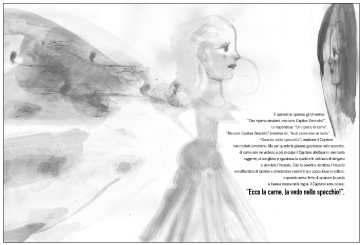

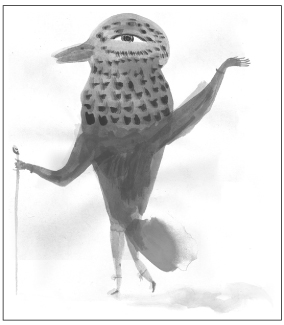

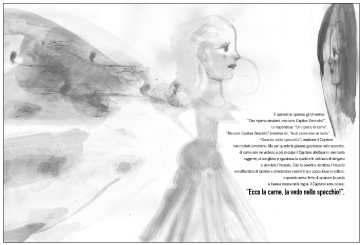

The extraordinary narrative power of this story has been greatly increased by the visually challenging metaphors created by the illustrator Fabian Negrin. His connotative illustrations have a strong aesthetic potential, they are full of ambiguous and controversial details and contribute to an emotionally pregnant atmosphere, without shying away from the feeling of disorientation that can arise when dealing with this kind of ambiguity and controversy. Children were indeed disoriented by the representation of Captain Murderer. They expected him to be depicted as a ‘real’ cannibal ogre and not as an elegant bird; a challenging intertextual reference to the bloody fairy tale Fitcher’s Bird mentioned above (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Fabian Negrin’s representation of Captain Murderer (Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006).

For these children, Fabian Negrin’s illustrations became a space for visual and aesthetic experimentation. The presence of visual symbols delivered a strong emotional impact and the ingenious visual metaphors stimulated children into looking at the images with astonishment and curiosity.

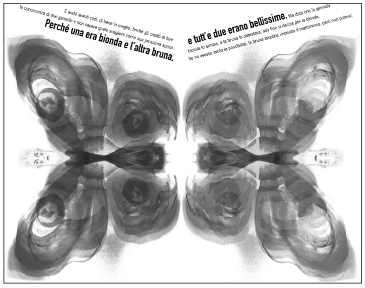

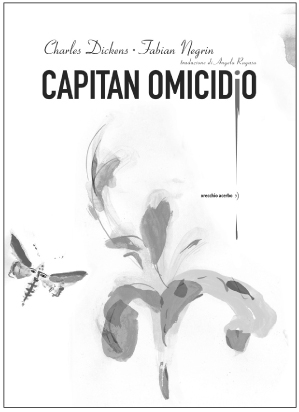

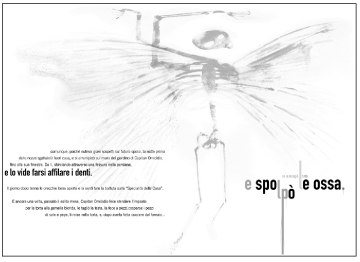

Seeing and interpreting the visual metaphors

Captain Murderer demands of the reader a visual multiple level of reading. The reader is actively involved in the Gombrichean ‘seeing and interpreting’ process described earlier in order to grasp the meaning of the story. An example of this excellent use of visual metaphors can be seen for instance in the presence of a flower, the iris, never mentioned in the verbal text. This beautiful flower can be seen not only on the front cover (Figure 6.3), but also on the endpapers (Figure 6.4) and inside the book (Figure 6.5) (Plate 25).

The iris is a metaphor. The children liked the inclusion of the flower and although they never explicitly wrote about it, they did, on a few occasions report that this flower referred to something ‘good’, ‘reassuring’ and ‘related to the butterflies’. Their intuition was surprisingly close to the undisclosed symbolic

Figure 6.3 Irises on the cover: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

Figure 6.4 Irises on the front endpapers: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

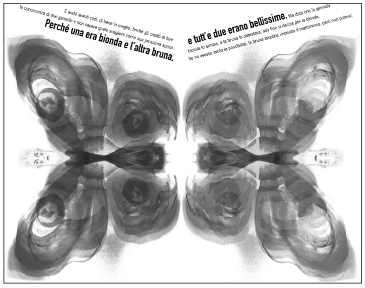

Figure 6.6 The two sisters became Captain Murderer’s wives: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

meaning of the visual metaphor because in effect this flower has a double meaning: on the one hand it stands for good news; on the other it implies a symbolic reference to the Greek goddess Iris, messenger of the gods, classically depicted as a young and radiant woman, her wings the diaphanous and iridescent colours of the rainbow. According to Greek mythology this goddess, very similar to a butterfly, was chosen to take dead women’s souls to the Elysian Fields (Figure 6.6).

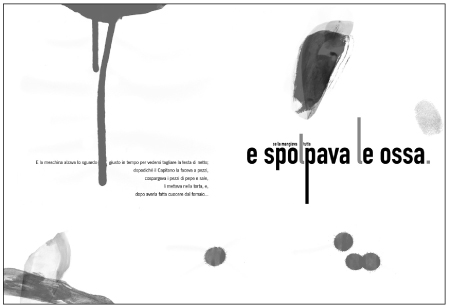

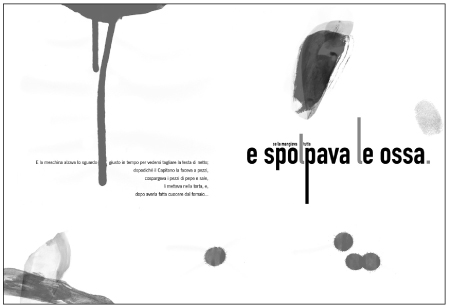

Figure 6.7 Bloodstains from Captain Murderer’s wives: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

In the picturebook Negrin depicted Captain Murderer’s wives as butterflies and this visual metaphor (absolutely not present in the verbal text) had a great emotional impact on the children. It really enhanced their curiosity about the unusual but ‘appropriate’ aesthetic choice of the illustrator.

At the beginning of the research project, this visually ambiguous and controversial picturebook disturbed both children and adults, some of whom had conflicting (and negative) reactions towards this picturebook until the end of the observational research. The adults considered the story completely inappropriate for reading to children aged 6, 8 and even 10 years and thought that the bloodstains and the cannibalistic elements would scare children (Figure 6.7).

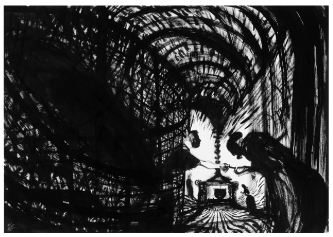

Despite the adults’ resistance and their negative reactions to this picturebook, the children were absolutely fascinated by it. They were certainly frightened by the story but they would not have stopped it from being read to them. The sense of wonder, the thrilling plot, the visual enigmas definitely enchanted them, as is evident from the ethnographic notes made when the book was being read to the 10-year-old children (Figure 6.8).

The researcher takes the book, a lot of the children had seen it before but Gastone asks to see it:

Ben: It’s gruesome.

Gildo: Even the title is scary.

The researcher begins reading and everyone moves closer to the book except Bianca and Perla.

Viviana: He eats women...

Perla comes a bit closer.

The children are silent and very attentive....

Gastone: The bride was the ingredient! [Figure 6.9]

Ethnographic notes of 15 March 2010

Figure 6.8 One of Captain Murderer’s wives: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

Figure 6.9 The death of one of Captain Murderer’s wives: Capitan Omicidio, Dickens & Negrin, 2006.

Two months of picturebook reading and visual comparison allowed the children to refine their ‘seeing and interpreting’ ability and to gain an aesthetic awareness as readers. Billy’s journal reflected this awareness:

Well I liked everything we did, but the best thing was that you told us ‘to see’ and then ‘to look’ because it’s a good painting technique.

Billy (aged 10)

In Captain Murderer the illustrations, which acted as receptors, enriched the reading activity with riddles; after some initially unsuccessful attempts, these children formulated some interesting interpretative hypotheses. This triggered off a positive mechanism that encouraged them to look for other visually enigmatic details. It was through this process of research and interpretation that Captain Murderer increased its charm and fascination.

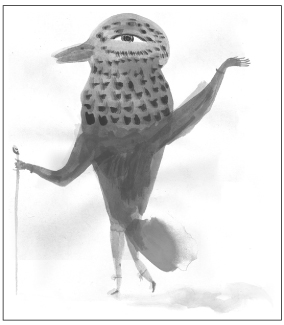

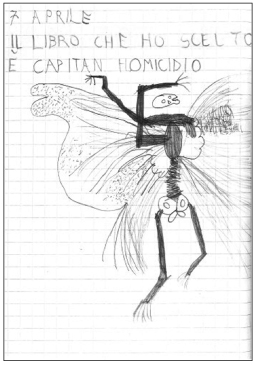

At the end, children were captured by the emotional landscape and the narrative tension emerging from Captain Murderer. The combination of Dickens’ thrilling comic–macabre story and Negrin’s fascinating, inconsistent and challenging visual metaphors made Captain Murderer the picturebook most chosen by these children. One of the 6-year-old children drew his preferred picturebook (Figure 6.10).

Figure 6.10 ‘The picturebook I preferred’. Drawing from the journal of a child aged 6 involved in the observational research.

Conclusion: shaping the young readers’ visual and aesthetic curiosity

If during the pre-school period children like to build daring controversial and metaphorical associations even in different semantic areas, it is during the primary school years that they gradually give up the habit of using symbolic and figurative languages to read and interpret external and inner reality. It is a great loss because they thereby lose some of the antibodies that can help them to counter and fight against visual cultural conditioning.

It is crucial to ensure that children have access to books that make use of figurative language and to bring this kind of language, even in its darkest and controversial versions, into classrooms. Moreover, ambiguous and controversial picturebooks are a valuable instrument in cultivating this mental attitude, because they can induce in the reader astonishment and curiosity and allow him/her to undertake a process of discovery and research.

Children’s desire to be presented with very realistic pictures must be satisfied. However, if teachers and educators offer young readers books that satisfy their natural need for concreteness and realism, they should also offer them books that make appropriate use of symbolic language, books whose visual validity depends above all on rich and complex aesthetic contents. This visual mode of representation gives space for things to be undisclosed and unsaid and encourages children’s interpretive involvement. It is a precious tool that allows children to experiment with the relativity of points of view. In order to encourage this, it is essential to arouse children’s curiosity.

Curiosity is a resource that a shrewd teacher should be able to call upon and exploit in the reading processes. As Maria Chiara Levorato (2000) points out, curiosity, as well as interest and wonder, plays a strategic role in the development of cognitive and aesthetic awareness. Curiosity activates a state of excitement that provides the child with the impetus to look for and discover new sensations, experiences and knowledge. Curiosity stimulates children’s thoughts. Since children are often attracted by what is different, mysterious and forbidden, wouldn’t it also be advisable to recommend to them strong controversial picturebooks?

While Captain Murderer was being read these children were silent and completely involved. The gruesome aspects of the book held their attention: their tension was palpable and engrossing. Each picture increased their thrilling expectations by offering a new visual enigma. With each page their worst doubts were continuously reinforced by the ambiguous and controversial details.

The Gombrichean approach ‘to see is to interpret’ shows that challenging visual explorations in picturebooks can effectively stimulate the reader’s aesthetic response, feed his/her curiosity and shape his/her taste. Last but not least visually challenging picturebooks are a powerful tool for enjoying reading.

At the end of this research the main question is not whether a visual mode of representation is appropriate or inappropriate for a child, or whether ambiguous or unambiguous picturebooks can shape young readers’ taste. The main question is whether teachers and educators are well enough ‘equipped’ to share with children challenging controversial picturebooks because children surely are.

Note

Academic references

Arizpe, E. & Styles, M. (2003) Children Reading Pictures: Interpreting Visual Texts. London: Routledge.

Arizpe, E., Colomer, T. & Martínez-Roldán, C. (eds) (2014) Visual Journeys through Wordless Narratives: An International Inquiry with Immigrant Children and The Arrival. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Barthes, R. (1977 [1964]) Rhetoric of the image, in Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

Barzilai, S. (2004) The Bluebeard barometer: Charles Dickens and Captain Murderer. Victorian Literature and Culture 32: 505–524.

Campagnaro, M. (2012) Narrare per immagini: uno strumento per l’indagine critica. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia.

Campagnaro, M. & Dallari M. (2013) Incanto e racconto nel labirinto delle figure. Trento: Erickson.

Colomer, T., Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. & Silva-Díaz, C. (eds) (2010) New Directions in Picturebook Research. New York: Routledge.

Davey, N. (2011) Gadamer’s aesthetics, in Edward N. Zalta (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/gadamer-aesthetics/

Evans, J. (2009) Talking Beyond the Page. Reading and Responding to Picturebooks. New York: Routledge.

Gadamer, H.G. (1986) Die Aktualität des Schönen, Kunst als Spiel, Symbol und Fest. Stuttgart: Reclam Philipp Jun.

Gardner, H. (2009 [1983]) Formae mentis. Saggio sulla pluralità dell’intelligenza. Milan: Feltrinelli.

Gombrich, E.H. (2002 [1960]) Arte e Illusione. Studio sulla psicologia della rappresentazione pittorica. Milan: Leonardo Arte.

Hamelin (2012) Ad occhi aperti. Leggere l’albo illustrato. Rome: Donzelli.

Levorato, M.C. (2000) Le emozioni della lettura. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Linstone, H.A. & Turoff, M. (eds) (1975) The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2006) How Picturebooks Work. New York: Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Pantaleo, S. (2008) Exploring Children’s Responses to Contemporary Picturebooks. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Salisbury, M. & Styles, M. (2012) Children’s Picturebooks. The Art of Visual Storytelling. London: Laurence King.

Schwarcz, J. (1982) Ways of Illustrator: Visual Communication in Children’s Literature. Chicago: American Library Association.

Sipe, L.R. & Pantaleo, S. (eds) (2008) Postmodern Picturebooks. Play, Parody and Self-Referentiality. New York: Routledge.

Tatar, M. (2004) Secrets beyond the Door: The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Almodóvar, A.R. & Taeger, M. (2009) La vera storia di Cappuccetto Rosso. Florence: Kalandraka.

Children’s literature

Browne, A. (2003) Hansel and Gretel. London: Walker books.

Carrer, C. (2005) La bambina e il lupo. Milan: Topipittori.

Carrer, C. (2007) Barba-blu. Rome: Donzelli.

Cinquetti, N. & Cimatoribus, A. (2009) Barbablù. Milan: Arka.

Cinquetti, N. & Morri, S. (2006) Cappuccetto Rosso. Milan: Arka.

Cousseau, A. & Crowther, K. (2007) Dentro me. Milan: Topipittori.

Dickens, C. (1860) The Uncommercial Traveller. London: Chapman and Hall.

Dickens, C. & Negrin, F. (2006) Capitan Omicidio. Rome: Orecchio Acerbo.

Grimm, J. & W. (1992 [1857]) Tales for Young and Old (Kinder- und Hausmärchen). Turin: Einaudi.

Grimm, J. & W., & Auladell, P. (2008) La casetta di cioccolato. Florence: Kalandraka.

Grimm, J. & W., & Janssen, S. (2007) Hänsel et Gretel. Paris: Éditions Être.

Grimm, J. & W., & Mattotti, L. (2009) Hänsel e Gretel. Rome: Orecchio Acerbo.

Grimm, J. & W., & Orecchia, G. (2005) Hansel e Gretel. Milan: Fabbri.

Grimm, J. & W., & Pacovská, K. (2008) Cappuccetto Rosso. Milan: Nord-Sud.

Grimm, J. & W., & Valentinis, P. (2005) Cappuccetto Rosso. Milan: Fabbri.

Grimm, J. & W., & Zwerger, L. (2003) Cappuccetto Rosso. Milan: Nord-Sud.

Lesser, R. & Zelinsky, P. (1999) Hansel and Gretel. New York: Puffin books.

Lionni, L. (1999) Piccolo blu e piccolo giallo. Milan: Babalibri.

Messenger, N. (2005) Imagine. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press.

Perrault, C. & Battut, E. (2001) Barbablù. Trieste: Bohem Press.

Perrault, C. & Claverie, J. (1995) Barbablù. Trieste: Emme Edizioni.

Perrault, C. & Ligi, R. (2005) Barbablù. Milan: Fabbri.

Piumini R. & Altan, F. (2008) Barbablù. Trieste: Edizioni EL.

Piumini, R. & Cantone, A.C. (2005) Hansel e Gretel. Trieste: Edizioni EL.

Piumini, R. & Sanna, A. (2005) Cappuccetto Rosso. Trieste: Edizioni EL.