Playing with the mind in wordless picturebooks

Sandie Mourao

Beginning with an overview of wordless picturebooks and how they can be interpreted, this chapter shares a small piece of research around the wordless picturebook, Loup Noir, created by the French illustrator Antione Guilloppé. It considers how children’s cultural frames of wolves affected their responses to the picturebook. The context and project are described and transcriptions of three groups of children interacting with the picturebook, together with their written stories, support discussion around their response. Discussion highlights the variety of ways these children responded, the creation of opportunities for collaborative talk, and the role our cultural frames play in our interpretations of ambiguous visual narratives.

Wordless picturebooks

Wordless picturebooks are considered a ‘distinct genre or sub-genre’ (Beckett, 2013: 83) and since the 1990s they have become not only a contemporary publishing trend but also highly sophisticated pieces of literature. The latter has resulted in many wordless picturebooks belonging to the crossover phenomenon and appealing to readers of all ages (Beckett, 2013).

A wordless picturebook has been defined as ‘a narrative contained within a book format, essentially based on the sequencing of images (...), whereby the page is the unit of sequence’ (Bosch, 2014: 71). Nevertheless, no book is completely wordless: Bosch (2012) characterises wordless picturebooks depending on how many words they contain. There are words in the editorial credits, the title and the name(s) of its creator(s), and a wordless picturebook can contain some words on its pages or the covers (an almost wordless picturebook), or it may appear at first glance wordless, but contains any number of words either concentrated onto one page or repeated single words or expressions throughout (a false wordless picturebook).

Wordless picturebooks are usually considered more open to interpretation than picturebooks, as no written text is available to anchor the creator’s original meaning (Serafini, 2014), and as Bosch states, ‘the more words a wordless picturebook has the greater the amount of information the reader receives’ (2014: 76), which will subsequently affect the reader’s interpretations of the book’s sequential visual narrative, thereby restricting its ambiguity. Thus, the title can be highly significant in leading a reader’s interpretation of a wordless picturebook, as are the summaries on the back covers. A wordless picturebook is therefore rarely completely wordless; it is dependent upon the sequence of images therein together with the few words it may contain.

Interpreting wordless picturebooks

The reading of wordless or almost wordless picturebooks is considered as challenging, if not more so, than picturebooks with words (Durán, 2002; Nodelman, 1988). Nodelman points out the requisite for ‘close attention and a wide knowledge of visual conventions that must be attended to before visual images can imply stories’ (1988: 187). These conventions include the significance of media, colour and style, which all contribute to a depiction of mood and atmosphere, as well as the visual grammars of left and right or high and low placed figures or illustrations, indicating not only cause and effect but status amongst and between depicted characters or objects (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996).

Finding a story from a sequence of images is likened to doing a puzzle (Nodelman, 1988). Ramos and Ramos translate Van der Linden, who believes that:

[readers leave] the comfort of the spectator of sound and image demanded by a picture story book read aloud and have to take the role of actors and even of ‘activators’ of a mechanism of a different nature based upon decrypting, setting relationships, inferring, as in all other acts of reading.

Ramos & Ramos (2011: 327)

Ramos and Ramos (2011) go on to describe readers entering into a ‘productive dialogue’ when looking at a wordless picturebook, as they look at the images seen both in isolation and in sequence. In so doing, readers create semantic inferences, which lead to hypotheses and expectations, all based on their personal experiences and understandings of the world at that moment, as well as on the cultural frames and social constructs relevant to any one group. According to Lakoff, ‘frames are mental structures that shape the way we see the world’; they form part of our subconscious in such a way that when we hear a word or see an image ‘its frame (or collection of frames) is activated in [our] brain’ (2004: xv). Gee, similarly, uses the term ‘cultural models’, defining these as ‘descriptions of simplified worlds in which prototypical events unfold (…) they are taken-for-granted assumptions about what is “typical” or “normal”’ (1999: 59). If we were to think of a wolf, our cultural frame would activate the image of a fierce, dangerous animal that is more likely to attack a human than befriend one. A taken-for-granted assumption is that a wolf is bad. Upon looking at a picturebook our cultural frames will also influence what we see – socially constructed ideas will contribute to our interpretation of the images.

As the reader moves through a wordless picturebook their interpretations are confirmed or challenged by each image or sequence of images and subsequently adjusted. Jauss describes this as becoming ‘aware of the fulfilled form of the [text], but not yet of its fulfilled significance, let alone its “whole meaning”’ (1982: 145). The creator of any piece of literature, with words or not, leaves interpretation to the reader, resulting in not just one but any number of interpretations. Meaning is neither given by the text nor the reader but instead is co-created in ‘the transactional process of meaning making’ (Rosenblatt, 1995: 27). The notion of a textual gap (Iser, 1978) is central to reader response theory, a theory which values the reader in the co-creation of meaning. Pictures and words, in effective picturebooks, interact with each other, either wholly or partially filling each other’s gaps or creating their own (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006). In wordless picturebooks the icono-textual gap is thought to be larger, as the reader elaborates hypotheses without knowing what is significant or what may happen next; it is ‘the degree to which readers are expected to actively engage which marks the difference between picturebooks with and without words’ (Arizpe, 2013: 163). Wordless picturebooks therefore engage readers to a greater extent based not only on the lack of direction provided by words, but also through the very non-linear nature of the iconic sign, through their very ambiguity.

Loup Noir: a wordless picturebook that challenges cultural frames

In the wordless picturebook Loup Noir (Black Wolf) Antione Guilloppé (2004), plays with readers’ subconscious and the cultural frames we create around wolves. Loup Noir is a visual narrative in black and white showing the journey a young boy makes through the woods on a cold, snowy night. As the boy walks he is followed by a wolf, at times the wolf looks menacing and as readers we assume the wolf will harm the boy, especially when we see the wolf leaping towards him in a later spread. Contrary to expectations, the wolf saves the boy from being crushed by a falling tree and they hug as though long lost friends.

Guilloppé very skilfully uses the simplicity of black and white, together with extreme perspectives, to create suspense and fear, knowing that the reader will think the worst of the wolf in his story. However, we see black predator replaced by white saviour in the later spreads. The different emotions evoked by each spread are a result of Guilloppé’s skill in positioning the figures, as well as his use of both black and white as colours which evoke fear or calm. As readers we move back and forth between the pages piecing together the puzzle. Our expectations and assumptions change as each page turns and further visual information is added to our interpretations. The reader is led to believe right up until opening 11 that the wolf will harm the boy, and seeing them hug on opening 12 catches us unawares, mainly, I believe, because stereotypical wolves are not creatures we would hug.

Guilloppé plays with our subconscious right from the start. The front cover (Figure 9.1) is black except for a pair of slanting eyes, the words of the title Loup Noir (Black Wolf) and the series name, ‘Les Albums Casterman’, all in white. If we understand the title we assume the eyes belong to the wolf. Black is stereotypically associated with both fear and death (Pastoureau, 2008), so we are most likely to assume it is a bad, bad wolf.

The back cover, also in black and white, displays the editor’s summary written in white on black:

It’s cold, the edge of the wood emerges as a silhouette against the backdrop of the night. The wolf watches, it lurks. The boy walks a little faster. The wolf appears, he leaps... A story to make you tremble in bed. [Own translation.]

As noted by Bosch, editorial introductions can ‘over-inform and are inclined to reveal too much about the form, content and the way the reader should read a book’ (2014: 87). This summary already directs our reading of the pictures. We can expect to see a wolf and a boy. We can expect to see a wolf lurking, a wolf leaping, and finally we can expect to be frightened as we read this picturebook.

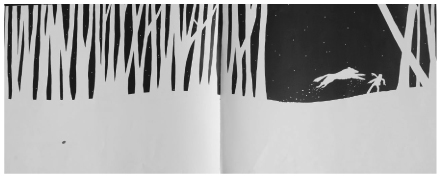

The body of the book continues to play with stark black and white illustrations. Sometimes the night sky is black sometimes it is white. Each time it serves as a background to silhouette figures or objects portraying a cold snowy landscape, sometimes scary, sometimes not. Some openings are doublespreads, others are two facing pages interacting cleverly, despite being separate (Figure 9.2).

On the verso page we see the boy from inside the wood, he is standing at the edge, about to enter. The trees and boy are black, the sky is white, and the trees lean inwards creating a menacing feeling, a tension, almost blocking the boy’s passage. This feeling of tension is accentuated by the illustration on the recto showing the wolf, black with white eyes and angular branches crossing the lower part of his face. Despite being separate illustrations they interact with each other. The wolf is facing left, looking towards the boy. The boy is looking into the forest, unknowingly at the wolf.

Figure 9.2 Opening 2, Loup Noir: Recto and verso illustrations interact with each other.

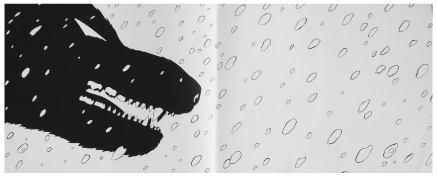

Figure 9.3 Opening 7, Loup Noir: The wolf’s head, black against white.

Guilloppé uses close ups to bond the reader to the boy, as well as to reinforce the reader’s fear of the wolf.

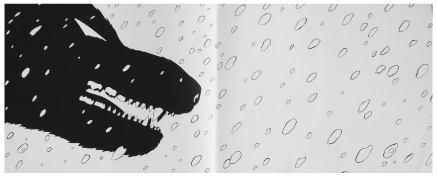

In opening 7, we see a close up of the wolf’s head, black against white (Figure 9.3). His teeth are white in his open jaws, his eye almost closed and menacing. We can clearly see his fangs and his molars and the falling snow, which is now thicker, could almost be falling teeth outlined in black against the white background. It is a frightening picture and it confirms everything we think we know about wolves. We are indeed made to tremble and fear for the boy’s safety.

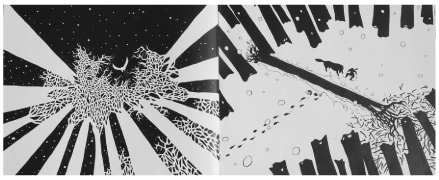

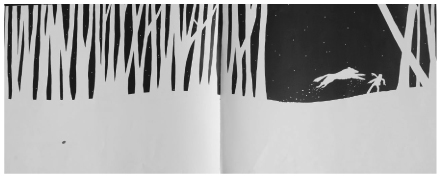

Black and white are used alternately, the trees, the boy, the wolf, all move from black to white depending on the emotions Guilloppé wants to evoke or what he wants to emphasise. The readers see the moment the wolf becomes white in opening 9 (Figure 9.4). Our hearts are beating fast by the time we reach this opening. We see a stark, mostly white page, divided into top and bottom. White foreground with white tree trunks close together along the top half of the verso. But our eyes are drawn to the black sky in the top centre of the recto page, and the silhouetted figures of a pouncing wolf and a frightened boy, both in white. To their right are more trees and one is leaning precariously to the left. It subconsciously enhances the already high tension. The wolf is going to harm the boy.

Figure 9.4 Opening 9, Loup Noir: Black wolf becomes white wolf.

Figure 9.5 Opening 11, Loup Noir: Different perspectives surprise the reader.

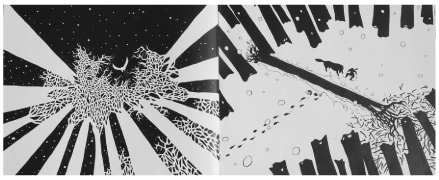

Guilloppé also uses different perspectives to surprise us. The verso of opening 11 (Figure 9.5) shows a worm’s eye view of the owl, flying high above the leafless treetops. The trees, in white, tower upwards in an exaggerated perspective, the owl is flying away. The recto is a bird’s eye view, looking down upon the wolf and boy, both small and black against the white snow. Is this what the owl sees? As readers, we finally understand that the tree has fallen into the path and that the wolf has, though we are still not sure, saved the boy from being crushed. Is this why the owl is leaving, because he knows the boy is safe as the tree did not crush him?

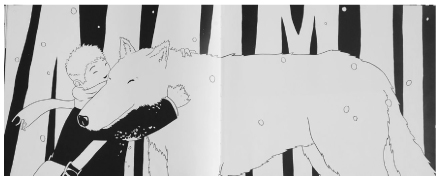

Opening 12 is the surprise (Figure 9.6). A doublespread close up of the wolf being hugged by the boy. Both are smiling. The wolf’s eyes are closed, so we have lost the menacing look from previous illustrations, and he is white and fluffy. The boy’s hug is heartfelt, so much so his hands dig deep into the wolf’s fur. The wolf dominates the opening, in his huge whiteness, pushing blackness out of the illustration – it is seen only in the boy’s coat and peeking between the white tree trunks in the background. So what happened? The wolf saved the boy, but were they already friends? Is he a wolf? Could he be a dog?

If we turn this last page we come to the back endpapers, which show the black night and the white snow of the front endpapers, but this time there are white, silhouetted trees at the far left of the verso and a cluster of white squares in the far recto. Could these be the lit windows in blocks of flats at the edge of the forest? Could these flats be where the boy lives?

Guilloppé’s French title translates as ‘Black Wolf’, a nominal title with black as an adjective. Our attention is focused upon the wolf, the bad wolf, even before we open the book. On the other hand, the title could be seen as contradictory, for the wolf is anything but menacing in the final opening, where he is depicted as white as snow. Guilloppé has created a picturebook that makes the reader question what they see. Is the wolf really a wolf?

In comparison to this, if we look at the English translation of this wordless picturebook, it has a very different title, One Scary Night (Guilloppé, 2005). This is a narrative title, ‘summing up the essence of the story’ (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006: 243): indeed it was a scary night, for the boy and the reader at least. In this case the focus is on the events of the night, and our attention is directed towards the boy’s experience. Additionally, this title allows the reader to consider the wolf might not be a wolf at all; he could even be the boy’s dog. This title leaves us with fewer questions. Nodelman (1988) reminds us that titles in wordless picturebooks determine our response to them – a title makes a difference.

Contextualising the research

Having read Guilloppé’s wordless picturebook, Loup Noir, I was left with many unresolved questions. I wondered how children would ‘interpret’ the book and this led me to use it with a group of children. I wanted to know what they would make of the narrative and how they would respond to Guilloppé’s deliberate play on the stereotypical belief that wolves are bad. Thus, with a view to observing how children’s cultural frames affected their interpretation of Guilloppé’s Loup Noir, I set up a small-scale project in a primary school in Portugal. This chapter continues with a description of the children and how I set up the project. It is followed by a discussion around the children’s responses to Loup Noir and the stories they created from looking at it together.

The children I worked with attended a state primary school in a predominantly low socioeconomic suburb of a city in Portugal. They were Portuguese, aged 8 to 9 years old and spoke Portuguese with me. Their teacher was an enthusiast of authentic texts – unusual in the Portuguese education system where textbooks dominate learning approaches; because of this the children were familiar with picturebooks as a source of pleasure. They were also experienced in talking about their interpretations during shared readings and were able to use picturebook meta-language quite successfully. Prior to reading Loup Noir the children had not read any wordless picturebooks with their teacher.

Preparing for the research

I did not know the children; thus to contextualise my visit and the activity, the classroom teacher and I planned a small project that involved all the children in the class. Prior to the activity the children were told that three groups of three children would look at a wordless book, then help each other to write a story for their classmates to illustrate. The final stage was to be the creation of an e-book from each story. In this way the children would together become collaborative authors and illustrators of their own books. The end product, the creation of three illustrated class-made e-books, (which was part of their ongoing class work with the teacher), provided a real reason for giving words to a wordless picturebook. The teacher felt there would be a number of opportunities for the children to work on their writing and illustrating techniques; I would be able to work with a group of children and gather some data; and the children would also benefit from the experience. Additionally, for my purposes, the group writing activity meant that the children’s thinking, feeling and reflecting would be more evident as they discussed what they would write. According to Hornsby and Wing Jan (2001), writing also enables children to reflect further by making connections they may not have made before.

Portuguese children are much like children in any Western country; they are led to believe that wolves are wild and dangerous. Through exposure to traditional stories such as Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Little Pigs and The Seven Little Kids they see wolves depicted as baddies. In an endeavour to keep the children’s previous cultural perceptions of wolves at bay it was decided to introduce Loup Noir with no preparative discussion.

The procedure: working with the children

The nine children were selected by their teacher from the class of 19. Each group of three children, made up of one girl and two boys, worked with me in turn for approximately one hour interacting with Loup Noir. Their voices were audio recorded and I took notes on what they did with their hands and bodies as they looked at the book and discussed it together.

The children first looked through the picturebook together without writing anything. This initial ‘storybook picture walk’ (Paris & Paris, 2001: 4) was adopted with a view to collecting the children’s initial impressions of the picturebook and their spontaneous physical and verbal responses. They could not read French, thus the title on the front cover did not initially influence their story interpretations (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006). Once they had seen the book, they were asked to think of a title and write the story they felt might accompany the pictures. All three groups looked at the picturebook several times before they began writing.

To write their story, the children each selected a role: the director, the scribe, or the editor. It was explained that the story had to be agreed upon by each of them, thus the director’s role was to decide what the scribe should write after listening to the other two. The scribe wrote their story and the editor helped the scribe and was also responsible for ensuring everything was written correctly when back in the classroom. During their collaborative creation of the story each group returned to the picturebook many times, moving backwards and forwards through the pages as they argued for certain interpretations, words and expressions and together decided what to write. The children’s comments and final written stories have been translated from Portuguese into English.

The children’s first encounters with Loup Noir

As the children shared their thoughts and discussed what they wanted to write it was evident that their preconceived ideas about wolves gradually changed from thinking of the wolf as a bad character to a good one.

Responses from Group 1

Upon seeing the book for the first time, Daniel pointed to the eyes on the front cover and exclaimed ‘a monster’, as the children turned the pages they quietly labelled the illustrations: ‘A boy’, ‘a wolf’, ‘an owl’. They then moved onto describing action. Here are their utterances from openings 9 to 12:

Opening 9

| Daniel: The wolf is trying to catch the boy. |

Opening 10

| Daniel: The boy fell to the ground. |

| Berta: And the tree, it almost caught the wolf. |

| Jorge: The tree fell [pointing to the tree trunk]. |

Opening 11

| Daniel: The boy is trying to escape after being pushed to the ground [pointing to the boy]. |

Opening 12

| Daniel: The boy is … |

| All: … giving a hug. |

| Berta: So they were playing? |

| Jorge: The wolf became the boy’s friend. |

This excerpt shows that right up to the final page turn, the children believe that the wolf’s intentions are to attack and hurt the boy. They notice the fallen tree in the illustrations but do not see any connection between this and the wolf’s leap. They conclude that the wolf and boy must have been playing, though Jorge is still not certain that they were already friends.

Responses from Group 2

Like the children in Group 1 these children begin by commenting on the front cover. Carlos says ‘Big wolf’ and Rui attempts to translate the title into ‘Night Wolf’, not because he can understand French, but because of the illustration; he also believes that ‘noir’ must translate into the Portuguese word ‘noite’, which means night – a logical assumption as the two words share their first three letters. From these initial comments one would think these children were fairly convinced that this story was about a wolf and indeed stereotypical wolf-related observations were scattered through their commentaries and responses. They label the wolf as ‘a monster’ (opening 2) and ‘an angry wolf’ (opening 6), and from opening 7 (see Figure 9.3), where the wolf’s profile shows bared teeth, they prepare themselves for a terrible ending. The transcription of their responses on these openings follows:

Opening 7

| Marta: [She points to the wolf’s teeth and counts under her breath] 22 white teeth so he can eat the boy. |

Opening 8

| Rui: The wolf was furious enough to eat this boy. |

Opening 9

| Carlos: Oooeee, he’s attacking him. |

| [Surprised and frightened noises] |

| Carlos: He looks like wolf man. |

| Rui: Yes he does. It’s all black and white. |

Opening 10

| All: Ahh eee. |

| Marta: Oh poor thing. |

| Carlos: The wolf grabbed the man. |

| Rui: This must be blood [pointing to black shape under their bodies]. |

| Marta: This isn’t blood, it’s a shadow, the wolf’s shadow. |

| Rui: He’s taken him by the throat, like this [dramatically holding his hands around his throat]. |

Opening 11

| Carlos: There’s the owl here [pointing at the owl] to save the boy. |

Opening 12

| Marta: Ahh, so sweet. |

| Carlos: So it’s not a wolf. |

| Rui: It’s a bear. |

| Marta: No it’s not, it doesn’t have... |

| Rui: It’s a polar bear. |

| Carlos: Maybe it is. |

| Marta: So sweet. |

| Carlos: Polar bears like the snow. |

| Rui: So in the end he didn’t attack the boy, he just wanted affection. |

| Carlos: That’s right, he jumped onto the boy because he wanted affection and that’s the end. |

We see that these children’s certainty of the wolf’s intent to harm the boy stays with them right up till opening 12 (see Figure 9.6) where his white goodness challenges the very idea that he is a wolf. On opening 10, Rui thinks the illustration represents blood, a difficulty we all have in interpreting black and white illustrations without the nuances of colour to depict clearly what something is. As a response to his first interpretation, he dramatically enacts the wolf grabbing the boy by his neck. Upon seeing opening 12, the children’s cultural frames are so deeply rooted that they no longer believe the creature to be a wolf. Instead they search for other stereotypes. Something sweet and white, that likes the snow and wants affection. It must be a polar bear. This association is one we make with soft toy polar bears, for we know a real polar bear is as dangerous as a wolf in the wild.

Responses from Group 3

These children leapt straight into the main body of the book, seemingly ignoring the cover. They skilfully talked their way through the illustrations, occasionally adjusting what they said to fit a visual sequence or justify a description, all examples of a ‘productive dialogue’, as mentioned earlier by Ramos and Ramos (2011). Comments from openings 2 to 4 are examples of this.

Opening 2

| João: And then he found a forest and saw some white eyes. |

| David: It looks like a monster. |

Opening 3

| Luisa: Ah it was a wolf. |

| David: Yes, it was a wolf, who was walking around. |

Opening 4

| David: No he didn’t know there was a wolf there and so because he didn’t know he kept walking. |

| Luisa: And then what happened? |

| David: He stopped and looked up and it was snowing. |

| Luisa: And after? |

In opening 3 David responds as though the boy in the book knew it was a wolf all along, but then he adjusts his narrative for opening 4 to allow for the boy to pause to catch snow in his hands. The children responded naturally to each other’s narratives.

There were a number of spontaneous ‘Oohs’, ‘Ahhs’ and shrieks and Luisa, in particular, made several loud exclamations. On opening 7 (see Figure 9.3), when Luisa sees the wolf’s head, she theatrically sucks in air, places her hand on her heart and cries ‘Oh goodness’. João accompanies her response with a dramatic narration: ‘The wolf opened his mouth, with his big teeth, and started growling’. They quickly turned the next four pages breathlessly relating their story, reaching the climax on opening 11 certain something terrible was going to happen.

Upon seeing opening 12, Luisa questions the illustration, ‘And then they became friends?’ But the boys continue their spontaneous storytelling, following the visual clues and finish as though it’s perfectly normal for a boy to hug a wolf, as the following transcription demonstrates:

Opening 12

| David: Yeah, and then the wolf says like this, ‘I just wanted someone who loved me’. |

| João: No the boy said, ‘I love you’. |

| Luisa: ‘I’m your friend’. |

| João: And they lived happily ever after. |

| David: The end. |

| Once over, João questions the twist, but David has the answers, as we can see from the next excerpt: |

| João: Really? The wolf wanted to attack him and then they became friends? |

| David: No, no he didn’t want to attack him. |

| João: But he jumped onto him. |

| David: To hug him. |

| João: [Turns book, looks at cover and points to the eyes] These must be the wolf’s eyes. |

| David: Like this, look [makes his eyes big and wolf-like and opens his mouth then hugs João]. |

| João: Woah, what a wolf. |

David not only evidently enjoyed the challenge of justifying his answers but he also used the picturebook as a platform for a dramatic, perfomative response (Sipe, 2000), pretending to be both a fierce and friendly wolf.

These two groups responded similarly in the sense that their emotions were evident – they experienced a ‘lived-through experience’ with the book, (Sipe, 2000: 270). The story world and the children’s world merge to become one, resulting in unconstrained responses, where the children showed the same fear the boy in the book experienced, as well as the same feeling of happiness, when they realise the wolf, or the bear, will not hurt them.

The children’s written responses: a discussion around titles

A title conditions our response to a picturebook; however, the children could not read the French title so nothing was pre-determined for them as such. Additionally, as already mentioned, the French and translated English titles lead the reader into very different stories. The French title, ‘Black Wolf’, prepares us for a scary wolf; the English one, ‘One Scary Night’, focuses on the boy’s scary experience, which could have involved any creature.

The children agreed upon titles which reflected their response to the wolf changing from bad to good at the end of the story; thus the titles were a direct result of their interpretations of the visual narratives. Group 1 called their story ‘The Lost Friends’, a title which is justified by Berta who explains, ‘(...) because the boy could have lost the wolf, and he was his friend, and so one day he went into the woods to find the wolf and he found him’. It is the relationship between the two characters that is important for these children.

The children in Group 2 who thought that the wolf was actually a bear, called their story, ‘The Bear in the Night’. This was a result of both their disbelief that a wolf could save a human and their feeling that words are ‘meaningful or important narrative details’ (Nodelman, 1988: 186), for Carlos made a connection with the written title, believing that ‘noir’ must translate into the Portuguese word which means night.

Group 3’s final title was narrative, ‘The Wolf Who Wanted Company’. The focus is on the wolf, but the emphasis is on a positive encounter he will have in the story, with someone who will become his companion. The children’s experience of the first reading left each of them with an idea for the title, which they supported with clear reasoning. David wanted ‘Wolf in the snow’ because there was a wolf and it was snowing; he showed opening 4 to support his idea. He then suggested that ‘The solitary wolf’ might also be a good title, justifying that ‘Maybe he needed a friend because everyone was afraid of him’. This comment suggests he expects all readers believe wolves are bad. Luisa proposed, ‘The wolf who wanted company’, because ‘he obviously wanted company as he threw himself at the boy to be his friend’.

João also latched onto the written title on the front cover, as Carlos had in Group 2. He too thought that ‘noir’ must be ‘noite’, so suggested ‘Wolf in the night’. He assured everyone that this was a suitable title as it was night in the story and showed several openings with a black night to support his argument. This led to the children noticing that in fact the night, and even the wolf, was illustrated in both black and white. João’s repeated insistence, supported by the possible presence of the word ‘night’ and the black wolf figure on the cover, did not persuade the others to go for his title. However, the discussion that took place between the children was an excellent example of ‘exploratory talk’; that is, talk ‘in which partners engage critically but constructively with each other’s ideas [and] relevant information is offered for joint consideration’ (Mercer, 2000: 98). What supports this kind of talk is the shared ‘contextual foundations’ – the picturebook and its illustrations – enabling the children to ‘reach joint conclusions’ (Mercer, 2000: 99).

Negotiating interpretations

All three groups produced stories that were initially more like descriptions of the illustrations rather than being ‘real’ stories, especially from openings 1 to 8. However, as the children’s stories progressed past opening 9, they reflected how each group had interpreted the ending, and structured the narrative associated to these latter openings. The following is an example from Group 1 (see Annex 1 for their final story), where at opening 10 they begin to prepare the reader for the twist. They insert the words ‘friend’ and ‘impulsively’, which relates to ‘just in time’ in opening 11. This connection was the result of a discussion led by Berta who, when deciding what to write for opening 10, admitted she didn’t understand the images.

Opening 9

| Berta: I don’t know why he attacked the boy. |

| Jorge: He attacked because he didn’t know that the boy was his friend. |

| Berta: Yes, so we write ‘The wolf jumped’ here. Then here [turns to opening 10]... |

Opening 10

| Daniel: He jumped on his friend to hug him. |

| Berta: Daniel, listen to a suggestion. Wolves aren’t domesticated. |

| Daniel: Right, they are wild animals. |

| Berta: Impulsively. The wolf jumped impulsively onto his friend. How do you spell impulsively? |

Opening 11

| Daniel: Yeah, then the wolf realised he was his owner. He recognised him right at that moment. |

| Berta: The wolf recognised his owner just in time. |

Opening 12

| Jorge: The wolf played with his friend. |

| Berta: So we don’t always start with the wolf, write the boy hugged the wolf. |

| Daniel: The boy hugged the wolf, he had missed him. |

Some interesting negotiation was taking place. Berta resorts to her knowledge of wolves to persuade Daniel that wolves are wild, so they instinctively jump at prey (opening 10). She suggests they use the word ‘impulsively’ to suit the wolf’s wildness. Berta in fact manages very nicely to rephrase parts of the narrative to make it sound better, using ‘just in time’ and insisting that opening 12 begin with ‘The boy’ as opposed to ‘The wolf’.

This co-creation of the story can be likened to the ‘cumulative talk’ referred to by Mercer (2000: 30). The children ‘build on each other’s contributions’ as they talk through their interpretations of the visuals. Mercer describes speakers being ‘mutually supportive’ and ‘uncritical’ as they co-construct ‘shared knowledge and understanding’ (2000: 31). The children are doing just this, even if Berta is slightly condescending at times.

Using illustrations to support interpretations

Group 2 had decided their story was about a bear and not a wolf (see Annex 2). However, Marta was not convinced. Their discussion shows their struggles with the decision to call the creature in their story a bear.

Opening 3

| Carlos: Now we have to write that the bear went after Pedro. |

| Rui: A short sentence. He decided to go after the young man. |

| Carlos: Woah, [pointing to the wolf on the verso] this looks just like a big bad wolf. |

| Marta: He wants affection. |

| Rui: It looks like one, but it isn’t. |

| Sandie: Do you still think it’s a bear? |

| Carlos: Yes. |

| Rui: I think it’s a wolf. |

| Carlos: Here it looks like one, but here, [showing the opening 12] it doesn’t. |

| Rui: Here [pointing to wolf in opening 3] it looks like one because of the shadow. |

| Marta: [Writing] He decided to go after the young man. OK, it’s done. Next picture. |

| Carlos: [Begins to turn the page] |

| Marta: Hold it. The wolf is sneaky [points at wolf]. This is just like a wolf, but anyway, no, a bear. Oh boy. |

Both Rui and Carlos do their best to justify that it is a bear by making reference to different illustrations, eventually relating the dark outline of the wolf in opening 3 to a shadow. Marta is not convinced as she still insists on calling the creature in the illustrations a wolf. She even shows some concern about their decision by exclaiming ‘Oh boy’ at the end of the extract. Later on, at opening 9, Rui actually instructs Marta to write, ‘Now you can put that the wolf jumps’. Nobody reacted to this and Marta responded, ‘Yeah, when the bear was really really close he jumped’. So, despite the children’s acceptance that their story was about a bear, they occasionally lapsed into calling the creature a wolf.

Entertaining spontaneous responses

Group 3 were highly entertaining to observe as they created their story. Upon reaching opening 11 (see Figure 9.5) the children decided their story might benefit from including direct speech, and the following excerpt shows the lead up to this decision at the end of their story (see Annex 3):

| David: The frightened boy was very still. |

| João: And the wolf looked at him. |

| David: And the boy did this [looking scared] ‘Huuuu’. |

| Luisa: [Imitating a frightened boy and recoiling using a squeaky voice] ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me!’ |

| David: We could have some speech here, couldn’t we? |

| Luisa: [In a squeaky voice] ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me!’ |

| João: Wait what do I write? The frightened boy was very still and then what? |

| David: And after a dash put ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me!’ |

| Luisa: ‘Don’t hurt me! Help me! I’m still a young boy.’ |

| David: And he said... No, he exclaimed ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me!’ |

| Luisa: ‘I’m still a young boy, I have my whole life in front of me.’ |

| David: ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me! Kill me on page 12.’ |

| Luisa: This isn’t page 12 it’s page 11. |

| David: OK. ‘Don’t let me die on page 11, let me die on page 12, so I get a couple more seconds of life.’ |

| All: [Laugh] |

| João: So don’t turn the page, as he hasn’t got long left. |

| David: So everyone has to die, right? |

| Luisa: Die? Yeah. |

| David: Everyone has to die when they’re old. |

| João: But he’s not old he’s a boy. |

It is evident that these children enjoyed this interaction, and it is an excellent example of spontaneous response. They have fun with the direct speech, where the children are seen to merge their identity with the picturebook and become one with it – I liken this to Sipe’s aesthetic response which includes ‘the desire to forget our own contingency and experience the freedom art provides’ (Sipe, 2000: 270). These children literally move in and out of role; first they are storytellers then they become the boy himself. David, in particular, is highly expressive and uses the picturebook as a platform for creative action. He plays around with the idea of prolonging life by not turning the page and obviously expected an ‘audience’ reaction – on cue we all laugh at his antics.

Concluding remarks

The children’s stories are all valid interpretations and as stories in themselves they show that the readers do indeed come to a text with their own expectations and personal experiences. These expectations are culturally framed and affect how the reader and text come together to create a new text. It was evident that children entered into a ‘productive dialogue’ (Ramos & Ramos, 2011) with the picturebook, which evolved as they read and reread the images and talked together about their interpretations. Many different stories emerged from the rereading(s), which were all influenced by what the children had experienced in relation to what they saw in the picturebook: each reread affected each interpretation and reformed interpretations. This was most evident in Group 2’s story featuring a polar bear.

It is of interest to note that none of the groups made the connection between the falling tree, in the visual narrative that runs through openings 9, 10 and 11, and the wolf saving the boy from being crushed. However, during the whole class reading of the picturebook with their teacher, João, from Group 3, noticed the diagonal tree in opening 9 and associated it with the fallen tree in opening 10. He then concluded, ‘So the wolf saw the tree was falling and jumped at the boy to save him’. Together the class then reconstructed the sequence, going back further to opening 8 where they thought that the boy, who is looking backwards in this illustration, did not hear the owl or the wolf, but instead the sound of the tree breaking and this was why he began running. They created a fourth story, which ended with the boy thanking the wolf for saving him.

The children used language skilfully to talk collaboratively about their interpretations of these sequential illustrations. The discussion highlights examples of cumulative and exploratory talk, which emerged from their conversations. Exploratory talk, in particular, is a result of people coming together, interacting and thinking collaboratively. Mercer refers to ‘interthinking’ as being ‘joint, co-ordinated intellectual activity which people regularly accomplice using language’ (2000: 16), and indeed interthinking was evident in these children’s interpretations and discussions. These children’s transactional interpretations successfully turned Guilloppé’s wordless picturebook into a word-full experience through collaboration and group work. Children were, in Van der Linden’s translated words, ‘actors’ and ‘activators’ (Ramos & Ramos, 2011) as they decrypted, inferred and created relationships between the boy, the wolf and even the owl.

The children’s finished stories are the result of multiple and very creative responses to the wordless picturebook, Loup Noir. I have attempted to give some indication of the richness of interpretation and the varying responses that I observed in the three groups of children. In all cases the children’s subconscious – their cultural frame in relation to wolves – was challenged. In the case of Groups 1 and 3, the children’s cultural frames became fractured as they gave the wolf in the book the opportunity to be friendly and pet-like. However, Group 2 felt so strongly that a wolf could not possibly befriend a human that they insisted the creature was a bear. Their subconscious, socially constructed ideas of what wolves were like completely swamped their interpretations. For these three children ambiguity in this wordless picturebook supported their creation of a narrative quite unlike any that Antione Guilloppé may have originally intended; but this is the right of the reader.

Annex 1

Group 1: The Lost Friends

A century ago, a boy was in a forest in the snow and he was very cold. He saw two strange eyes looking at him. It was the wolf who was following him all the way. It was night when the boy began to catch the snow with his hands. An owl saw some footsteps and then noticed that a boy was there with snow to his knees. The wolf’s strange eyes kept watching him. He opened his mouth wide and his teeth were as sharp as knives. The boy heard a noise and looked back. The wolf jumped. He jumped onto his friend, impulsively. Then he recognised his owner just in time. The boy hugged the wolf, he had missed him.

Annex 2

Group 2: The Bear in the Night

One night in the North Pole a young man called Pedro, who was 16 years old, was walking through the forest... A polar bear was also walking and he heard steps and decided to stop to see. He decided to look from behind some bushes and he saw the young man. He decided to go after the young man. The young man heard steps and noticed it had started snowing. The young man heard an owl, was frightened and started running. As he was running the young man realised he was being chased by an animal. The bear got closer and closer to the young man and he was furious. Pedro ran and looked back to see if he was still being chased. When the bear was very, very close to Pedro, he jumped. A tree fell as the bear jumped, and he fell on top of Pedro.

Pedro was frightened and fell into the snow and saw the bear was friendly. And in the end he gave the bear a big hug and they became the best friends in the world and happy.

Annex 3

Group 3: The Wolf Who Wanted Company

It was night. A boy, who was walking in the snow, became very cold. He kept on walking when suddenly two big eyes appeared from behind a tree. It was a wolf who was walking through the woods behind the boy. The boy looked up and it began to snow and he opened his hands in the shape of a shell. While he was walking he saw two big eyes and he thought they were a wolf’s eyes, but when he looked again he saw they were an owl’s eyes. He started to run. While he ran, the wolf ran too, watching him through the trees. Then the wolf lost the boy and, sensing danger, he started to sniff looking for him. The boy heard a noise and looked back. And the wolf leapt onto the boy. The wolf grabbed the boy with all his strength and they both fell. And the frightened boy lay quietly and exclaimed, ‘Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me!’ But the wolf did not want to hurt him, he just wanted a friend.

Academic references

Arizpe, E. (2013) Meaning-Making from Wordless (Or Nearly Wordless) Picturebooks: What Educational Research Expects and What Readers Have To Say, Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2): 163–176.

Beckett, S. (2013) Crossover Picturebooks: A Genre for All Ages. New York: Routledge.

Bosch, E. (2012) ¿Cuántas palabras puede tener un álbum sin palabras? (How Many Words Can a Wordless Picturebook Have?), Revista OCNOS, No.8: 75–88.

Bosch, E. (2014) Texts and Peritexts in Wordless and Almost Wordless Picturebooks, in Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (ed.) Picturebooks. Representation and Narration. Abingdon: Routledge.

Durán, T. (2002) Leer antes de Leer (To Read before Reading). Madrid: Anaya.

Gee, J.P. (1999) An Introduction to Discourse Analysis. Theory and Method. London: Routledge.

Hornsby, D. & Wing Jan, L. (2001) Writing as a Response to Literature, in Evans, J. (ed.) The Writing Classroom. Aspects of Writing and the Primary Child 3-11. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Iser, W. (1978) The Act of Reading. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Jauss, H.R. (1982). Toward an Aesthetic of Reception. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (1996) Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

Lakoff, G. (2004) Don’t Think of an Elephant: Know your Values and Frame the Debate. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green.

Mercer, N. (2000) Words and Minds. How We Use Language to Think Together. Abingdon: Routledge.

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C (2006) How Picturebooks Work. Abingdon: Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1988) Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Paris, A. & Paris, S. (2001) Children’s Comprehension of Narrative Picture Books (CIERA Report no. 3-012). Ann Arbor, MI: Centre for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement. www.ciera.org/library/reports/inquiry-3/3-012/3-012.pdf

Pastoureau, M. (2008) Noir. Histoire d’une couleur. Paris: Éditions Points.

Ramos, A.M. & Ramos, R. (2011) Ecoliteracy through Imagery: A Close Reading of Two Wordless Picture Books, Children’s Literature in Education, 42: 325–229.

Rosenblatt, L.M. (1995) Literature as Exploration, New York: Modern Language Association of America.

Serafini, F. (2014) Reading the Visual: An Introduction to Teaching Multimodal Literacy. New York: The Teachers College Press.

Sipe, L. (2000) The Construction of Literary Understanding by First and Second Graders in Oral Response to Picture Storybook Read-Alouds, Reading Research Quarterly, 35(2): 252–275.

Children’s literature

Guilloppé, A. (2004) Loup Noir. Paris: Casterman.

Guilloppé, A. (2005) One Scary Night. New York: Milk and Cookies Press.