FIGURE 2.1 College-Age Adults’ Memories of Childhood Play: Childhood Age

The Streeters had their first baby a year ago but they live over 200 miles from Joe Streeter’s parents. His parents visited at the time of the baby’s birth but they did not visit again until the baby, Jonah, was about 4 or 5 months old. When they observed the diaper-changing routine on the second visit, they were completely amazed at how efficiently that process was accomplished because Joe gave Jonah his iPhone™ to hold while he changed the diaper. Jonah spent the time quietly observing the animated designs on the phone and was completely absorbed in the phone rather than in his parent’s actions. Joe’s parents remembered spending time talking, singing, and playing baby games to hold Joe’s interest when they did diaper changing and they wondered what is gained and what is lost when technology-augmented devices become the focus of the baby’s attention rather than the parent during such routine daily activities that are involved in raising children.

Over the course of history, humans have made many technological changes to their environment to fulfill various human purposes or improve practical aims and solve problems. Older examples of such technology inventions that are still used today include tools such as forks, combs, shovels, hammers, and drums. Some of the earlier technology that resulted in major environmental manipulations and societal changes include transportation inventions (the wheeled cart, boats, trains, automobiles, and planes), clothing manufacturing methods (needles for sewing, looms, sewing machines), and communication tools (paper and writing tools, typewriters, telegraph machines). Early play materials for children such as dolls, rocking horses, and puzzles are also examples of ways that humans have changed and manipulated play environments through the design of objects that may or may not exist in the natural world. Thus, technological innovation has always been a part of human experience and most of these creations have altered human behavior (and possibly human brain maturation!) in various ways. Some of these technologies have enhanced specific aspects of human life (e.g., water purification systems) and some have had negative as well as positive consequences (e.g., hydraulic fracturing, genetically altered seeds). Because technology creates changing environments to meet human identified needs, it is a multidimensional concept, involving values and social consequences, and engendering various perspectives, some of which stress positive and life enhancing aspects and some that result in more problematic consequences. Often the same technology innovation may result in both positive and negative consequences for human life, and many of these consequences may be unforeseen when they are first initiated.

The technological innovations in present day society are affecting many aspects of modern life, including the play environments of infants, children, and adolescents. There are basic differences between the play environments of children growing up in earlier times and the present-day play environment. For example, children from previous generations had access to a greater range of “natural” play materials (rocks, sticks, streams) and to a much smaller range of deliberately designed play materials. Also, earlier play materials had few “active” qualities that enabled the toy to initiate child responses. Dolls may have made a crying sound when hugged, toy cars may have accelerated faster when pushed, and blocks shapes and sizes may have affected the types of buildings that could be constructed. However, for toys of the past, the most engaging qualities of the toys came from human action. That is, children’s voices made the doll “talk,” their active running made the plane “fly,” and their creative ideas made the small-world “story plots” that the toys enacted. These changes in play settings, materials, and experiences are likely to affect other aspects of human development, including human brain maturation. There is research evidence that adults of today remember somewhat different play experiences than adults of earlier times recall.

The authors have conducted a number of studies of what adults reported as their most salient childhood play and their views of its value. The first compared the memories of play of American and Chinese young adults (Bergen, Liu, & Liu, 1997). The second surveyed different groups of young adults at three different time periods and compared their remembrances of play and opinions of its value (Bergen, 2003; Bergen & Williams, 2008). Recently two more studies of the types of play at four age levels reported by college-age students have been conducted (Davis & Bergen, 2014; 2015).

The study that compared the memories of Chinese and American students found that both groups were comparable in regard to describing their remembered play as being primarily pretense and games with rules, and both groups described much of their play as being outdoors. The specific games and pretense themes differed, however. The second study, which compared results of the American student sample from the first study with results of two studies of later cohorts of students using the same procedures, found significant differences on a number of dimensions. There were 201 students in the 1990 study, 137 in the 2000 study, and 209 in the 2008 study. In all three groups pretense was the most reported type of play during the elementary age period, most of it occurring in private spaces (basements, yards) or with small-scale objects (dolls, action figures). Games with rules (ball games, traditional games) were the second most reported type of play at all time periods. Also, all groups reported they played outdoors but the earlier groups reported that their play ranged throughout their neighborhood and involved other children while the latter group reported more play in their own yard and playing alone about 25% of the time. The first group reported no play with technology-augmented play materials but the other two groups reported about 7–9% of their play being with such materials. At all three periods the major reason reported for play was “fun” and the two major types of learning from the play mentioned were “social skills” and “imagination/creativity.”

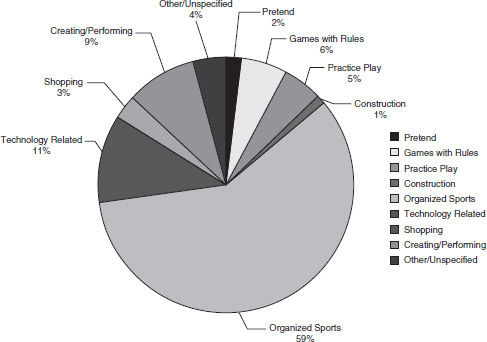

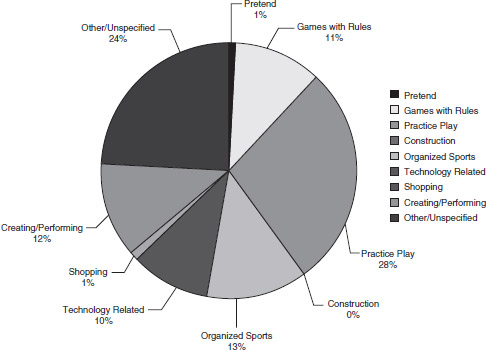

In the study Davis and Bergen conducted more recently, the college students described their play at four age levels: preschool age, elementary age, high school age, and college age. They reported that at preschool age the play included pretense with dolls and action figures, games such as hide and seek, practice play such as swimming or riding bikes, and technology play such as videogames and TV watching. At elementary age, their play continued to include pretense as well as games, including board games. Their reported practice play was similar to preschool age; however, construction with small blocks (e.g., Legos™) and building forts and other structures also were mentioned often. Technology play included video gaming with friends and computer game play. By adolescence, they did not report pretend play but they were involved in pretense-related activities such as being in plays and dancing, as well as involved in games such as bowling, biking and other active practice play. The types of technology play they reported included video games and play with online computer games. Figures 2.1–2.4 show percent of time reported for play activities at the various ages. Note that the percentage of reported technology-augmented play is greater at later age levels but that there is still a balance of reported play-related activities at later ages. All of these young people grew up, of course, before the advent of smart phones, tablets, apps, and other technology-augmented devices to which today’s children are exposed.

FIGURE 2.1 College-Age Adults’ Memories of Childhood Play: Childhood Age

FIGURE 2.2 College-Age Adults’ Memories of Childhood Play: Elementary Age

FIGURE 2.3 College-Age Adults’ Memories of Childhood Play: High School Age

FIGURE 2.4 College-Age Adults’ Memories of Childhood Play: College Age

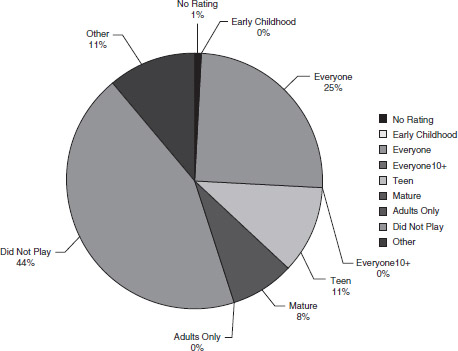

A subsequent study by Davis and Bergen (2015) specifically asked college students for information about their types of technology play at these same four age levels. It requested examples of video game and other technology-augmented play and also asked about online play experiences. The data show increased game playing during elementary and high school ages, and corresponding increases in play involving violent games as categorized by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (www.esrb.org). Figures 2.5–2.8 show the reported increase in such play at later ages.

These data also highlight the rapid expansion of social networking sites, because a large proportion of students reported that these sites were their favorites at high school and in college. Figure 2.9 shows the increase in social networking site activity as age level increased.

It is evident from these research studies that long-term changes in the play experiences of children and adolescents are occurring and that young children as well as older children are learning new behaviors and adapting earlier behaviors to the pervasive technology-augmented environment. Whether these changes will result in a diminishing of human possibilities or an enhancement of human possibilities is an open question.

FIGURE 2.5 ESRB Rating of College-Age Adults Reported Technology-Augmented Play: Preschool Age

FIGURE 2.6 ESRB Rating of College-Age Adults Reported Technology-Augmented Play: Elementary Age

FIGURE 2.7 ESRB Rating of College-Age Adults Reported Technology-Augmented Play: Adolescent Age

FIGURE 2.8 ESRB Rating of College-Age Adults Reported Technology-Augmented Play: College Age

FIGURE 2.9 Social Network Services Reported Preference Across the Ages

Although the body of research on effects of technology-augmented play is still relatively small (Wartella, Caplovitz, & Lee, 2004), a number of authors have expressed their views on the potential positive and negative effects of these changes in play materials. Their analyses are often widely different. Goldstein (2013) has stated that these devices have changed the play landscape because the players can not only play with the media but can change the shape of the games and, thus, this play also changes the players. He asserts that since toys have always been the means by which children learn about the values and practices of their culture, the technology-augmented environment is providing that cultural information today. In a discussion of effects of the pervasive technology-augmented culture, however, Levin (2013) argues that many of the cultural messages children receive are gender stereotypic or violent. She suggests that firsthand experiences communicated by families, teachers, and the community remain important.

Kafai (2006) has discussed how the feedback and feelings of control provided by video games can be valuable. She considers technology-augmented play materials as the new “playground” for today’s children and recommends that children play with programmable building blocks, computational game tool kits, and virtual playgrounds, which all provide constructive activity because these types of technology-augmented play can provide the same values as blocks, Tinker Toys, Legos, and other concrete building materials. She does concede, however, that many present interactive technology play materials “undervalue the constructive aspects of play in which children have always engaged” (p. 213).

Lim and Clark (2010) assert that virtual worlds provide almost all of the advantages that typical play provides. Many of today’s toys have an “online presence” allowing children to expand their world out of their “safe” home environment, thus taking the place of the wide-ranging neighborhood play of children in the past. Also, they state that online play with avatars expands the possibilities of imaginative play and supports “cultural convergence” and learning experiences. Jenkins (2009) suggests that the new skills learned through such play are ones needed in the future. For example, distributed cognition, identity performance, simulation, and navigation in multiple modalities are needed skills promoted by technology-augmented media. However, other writers state that the effects of highly specialized toys are currently unknown, and some research supports the view that these toys offer more negatives than positives. For example, after researching 3–6-year-olds’ play with the robotic toy AIBO™, Kahn and colleagues (2004) concluded that the play resulted in “impoverished” relationships.

Views of the effects of technology-augmented play materials often vary depending on the age-level of the children who are the focus of the technology. Thus, a recent product designed for infants that would permit an electronic tablet to be positioned on their “bouncy chairs” or “potty chairs” was highly critiqued by advocacy groups that are opposing such “electronic babysitter” apps being promoted as ways to help brain development by manufacturers of these devices (Kang, 2013). In fact, the American Academy of Pediatrics has stated that infants under age 2 should have no “screen time,” including time on mobile devices (2001, 2013). Similarly, adolescents’ pervasive use of apps on various devices has been questioned in a recent work by Gardner and Davis (2013) because these virtual connections give adolescents the feeling that they are having close connections but really their connections are shallow rather than deep and sustained.

The use of electronic tablets as learning devices for preschool and elementary age children and children with special needs also have been interpreted both positively and negatively. For example, one study reported that digital media use enhanced attention, concentration levels, and knowledge levels of young children (Plowman, Stevenson, Stephan, & McPake, 2012) while a review of studies measuring learning effects of such use with children with special needs concluded that most effects are small or mixed, although “engagement” is increased (Weigel, Martin, & Bennett, 2010). On the other hand, when a robotics program designed for improving literacy skills of low-income high school students was studied, results showed improvement in science literacy skills for one of the cultural groups and improvement in mathematics and literacy skills for another cultural group. The authors concluded that low-income students might find robotics instruction helpful (Erdogan, Corlu, & Capraro, 2013).

Although such changes in play experiences will be especially influential on brain development during the infant and preschool age periods due to the extensive “brain building” that goes on during those years, because brain maturation continues to occur throughout childhood and into the adolescent and young adult years, the types of play that are pervasive during the entire period of brain development will have lasting effects on the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development of the human species. Thus, it is important to have criteria for evaluating how the changing landscape of the play environment may affect long-term brain development and subsequent human evolution.

The authors have identified three ways to evaluate and understand the changing landscape of the play environment, which include examining the representation modes elicited, the affordances provided by the play materials, and the contexts within which they exist. These criteria may enhance human ability to judge the play-supporting features of technology-augmented play materials, to compare such features to those of typical play materials, and to speculate about their potential effects on the long-term development of children and adolescents, as well as on the human species as a whole. These criteria can be used to judge the play supporting features of technology-augmented materials and their potential effects on the development of play skills, brain development, and social engagement of children and adolescents.

Although there would be many ways to evaluate the influence of technology- augmented play materials, there are some constructs that seem to be especially suited to be used to consider effects on brain maturation, as well as on social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development. These include examining the representation modes, the affordances, and contexts related to technology- augmented play.

Bruner’s (1964) designation of the three representation modes that may affect levels of cognitive understanding can be used to evaluate the effects of play materials. Enactive representation (interactive motoric responses) of knowledge varies greatly with differences in play materials. For example, children use their whole bodies during play with balls or climbing equipment while they primarily use eyes, hands, and fingers when playing a video game. In many traditional types of play there is also involvement of the mirror neurons because interpretation of the actions of other players is needed for social play. These whole body and face-to-face human interactions appear to be essentially present for young children’s learning in many spheres, although such opportunities are more limited in many types of technology-augmented play. Iconic representations, on the other hand, are pervasively evident in many technology-augmented play materials. That is, the images on the computer screen “stand for” the actual objects and thus they are substituted for enactive experiences. For example, on the electronic tablet the pictures that stand for the “blocks” are stacked and the “bird” flies into a virtual sky.

The highest level of cognitive representation, the symbolic, which involves interpreting arbitrary code of language or other symbols, is also incorporated in many technology-augmented play materials, although this dimension varies with the complexity of such materials. For young children, there may be number or letter symbols that can be activated in various ways to “stand for” pictures of a number of objects or familiar animals. Young humans typically have engaged in all three of these representation modes during their developmental progress, so if there is a change in the balance of these modes of cognition during childhood, there may be some effects on social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development. Thus, one method of evaluating the potential effects of technology-augmented play is to examine whether the play materials involve one or more of these representation modes, and thus, potentially activate varied levels of social, emotion, moral, and cognitive engagement.

According to Eleanor Gibson, who studied how humans directly perceive objects, every object in the environment provides affordances that elicit actions. That is, they suggest the ways in which the object can be perceived and acted upon by the perceiver (Gibson, 1969). The affordances of objects and other environmental features can be directly perceived by individuals without the need for cognitive interpretations, and they can have a great effect on the actions of the perceivers. Affordances of materials may be general or they may be specific; that is, they may suggest many actions that the perceiver can do with the object or they may dictate a narrow range of actions. Thus, the affordances of an object may promote either routinized or creative interactions. Lauren Resnick (1994) has explained that cognition is “situated” and that young children construct cognitive schema (organizing designs that impose structure on the environment) when they “encounter environments with the kinds of affordances they need to elaborate these prepared structures” (p. 476). Thus, when children play, the types of affordances provided by various play materials may also affect cognitive development.

Carr (2000) has suggested three affordance criteria that are useful for evaluating the action potentials of various play materials. These criteria are transparency, challenge, and accessibility. In relation to play materials, transparency refers to the quality of the material that enables the player to understand the concepts inherent in the toy or object. When a toy or other play material has transparency, the player does not need to guess or try various approaches in order to understand how to interact with that toy. For example, a jigsaw puzzle has immediate transparency because it signals to players how it should be used and provides feedback to the players as to whether their performance in placing the pieces is accurate. A technology–augmented toy or a computer program that signals the child’s progress or success by triggering the toy’s actions also would have transparency. Conversely, a toy or other play object that requires extensive guidance or training in order to play with it appropriately would have less transparency. Of course, transparency also differs in relation to the age and experience of the player since older or more experienced players may recognize transparency in more difficult puzzles or video games. Papert (1980) has indicated that perceiving the physical affordances of objects can lead to the creation of mental schemes or models that increase the transparency and extend it to other domains of understanding. That is, more complex objects can become transparent if the player already has mental schemes that can be related to that object.

Carr’s second criterion, challenge, involves having affordances that increase the number of possibilities for action rather than narrowing the options to only a few actions. Some play materials, such as blocks and sand, have extensive possibilities for actions so they are high in challenge. A technology-augmented toy that requires only one type of reaction or interaction would have little challenge, but one that invites many interaction possibilities would have greater challenge. For example, a toy that makes the same sound each time one feature is pressed and that has no other manipulative devices would have low challenge, but if it makes a number of sounds that require varied responses by the child, it would have higher challenge, especially if different actions were required to produce each sound.

Carr’s third characteristic, accessibility, is related to the amount and type of social participation that a toy affords. For example, a game that involves parent-child or peer collaboration would be judged to have greater accessibility than one that requires no social interaction. Some types of toy technologies afford extensive social participation while others allow only one participator and have no social contact possibilities. Certain play materials (e.g., puzzles) can be used in a solitary way or as a collaborative activity, but there are others (e.g., board games and baseball bats) that usually require other participants. In regard to technology-augmented play materials, some invite social participation and some do not, although even those that have solitary components often have the capability of interaction with other players in distant places. Thus, this method of gaining virtual accessibility through internet access can enhance this accessibility quality of the play material.

All three of these affordance qualities interface; for example, transparency is more likely to facilitate accessibility, and challenge is usually increased if the other two factors are present. In evaluating the effects of technology-augmented play materials, therefore, analysis of their affordances in comparison to the affordances of traditional play materials is an important requirement. As is true of all play materials, those that include technological augmentations may promote transparency, accessibility, and challenge or the augmentations may diminish such qualities. However, the context in which they are presented also plays a part in determining which representation modes can be elicited and the extent of the influence of the affordances of a play material.

In regard to technology-augmented devices, an especially useful evaluative criterion is context. Context defines a setting, a circumstance, or the conditions present during an event or occurrence. It is important with respect to evaluation because it locates the evaluation within a frame in which other variables may have an impact. Without knowing the context, many questions are impossible to explore, and all evaluative results are incomplete. The general idea of context as it pertains to technology can be seen in the prior reflection on the definition of technology and in more practical examples such as the work done in defining context within content-aware computing (Dey, 2001; Dey, Abowd, & Salber, 2001). According to Dey and colleagues, information in both physical and electronic environments creates a context that affects the interaction between humans and computational services. They define context as information that characterizes entities that mediate the interaction between the user and the application. They state that context involves the “location, identity, and state of people, groups, and computational and physical objects” (p. 106) and indicate that every context involves interactions with “users, applications, and the surrounding environment” (p. 100).

The two major contextual categories of play with technological devices are defined as physical contexts and virtual contexts. These categories dominate the research landscape in reference to technology, primarily because of their flexibility and convenience. The distinction between physical and virtual is frequently seen in the literature on cyberbullying. For example, Patchin and Hinduja (2006) assert that technology can be implicated in the transmutation of bullying from the physical or real to the virtual or electronic. Similarly, Katzer, Fetchenhauer, and Belschak (2009) suggest that “bullying in internet chatrooms is not a phenomenon distinct from bullying in school. The primary difference lies in the context of action—virtuality vs. physical reality” (p. 32). Marsh (2010), however, states that play is primarily a social practice involving interactions with others and that this can occur “both in the virtual world and the physical world” (p. 32).

Physical and virtual contexts are generally accepted as different but not mutually exclusive constructs although there is some debate as to what exactly constitutes the two types of contexts. For example, Klahr et al. (2007) uses the phrase “real materials” (p. 185) to define the physical context and cites examples such as ramps, mechanical devices, and electronic items as real while limiting the virtual context to computer programs. Offermans and Hu (2013) add that the physical context (termed “world”) includes sharing experiences with parents, the social context, physical activity, and physical behavior, while the virtual world is interactive, dynamic, tailored, fostering exploration and identity development, and affording unusual experiences. Burbules (2006) argues that “the key feature of the virtual context is not the type of technology that it produces but the sense of immersion itself” (p. 37). He suggests that virtual contexts are not passive simulated realities but active experiences in which the individuals’ response and involvement create meaning. The “as-if” sense is maintained when the virtual experience is interesting and involving, engages the imagination, and is interactive.

In evaluating play experiences, Marsh (2010) noted that there is overlap between the physical and virtual categories and she suggests that technology advances may make these boundaries even more blurred. For example, she notes that although “rough and tumble play” is a term that typically describes physical wrestling and chasing, that term also can describe online play “that involved deliberate attempts by children to engage in avatar-to-avatar contact, including chasing and snowball fights, a form of play in which the majority of children interviewed reported having been involved” (p. 32). Klahr et al. (2007) agrees that virtual materials can have a similar range of action as can occur when “physical materials are used in the real world” (p. 185). In both the physical and virtual context, children can remain in control of the materials being used. Marsh (2010) defines play as primarily a social practice involving interactions with others and that this can occur “in the virtual world and the physical world” (p. 32).

FIGURE 2.10 Mixed-Reality/Virtuality Continuum

Milgram and Kishino (1994) proposed a taxonomy to discriminate between “real” and “virtual” and “mixed reality” venues. This “Virtual Continuum” describes two extremes “Real Environment” and “Virtual Environment,” with “Mixed Reality” spanning these. Mixed Reality is composed of “Augmented Reality” and “Augmented Virtuality.” Figure 2.10 shows this conceptualization.

In the taxonomy, Milgram and Kishino made three distinctions: 1) between real and virtual objects, 2) between direct and non-direct viewing, and 3) between real and virtual images. This taxonomy was designed to provide a framework that can unify seemingly disparate concepts and enable critical examination using common standards.

As technology advances, the contexts may continue to change. Within the analysis framework of this book, however, the term physical signifies real and tangible and virtual signifies mediation by technology-augmentation. This will enable readers to examine changes in the play landscape using this accessible perspective.

As technology has advanced over the centuries, these advances often have found expression in the toys and play of children. For example, during the industrial age, “mechanical” toys were available in a variety of forms and were usually activated when a button was pushed or a string was pulled. The toy actions, however, were relatively limited. A general look at toys in the 19th and 20th century reveal how certain representation modes and affordances were expressed, as well as the contextual environments in which the play occurred.

During the years of the 19th and 20th centuries, toys available to the majority of children generally promoted enactive and iconic experiences, with symbolic experiences occurring at much later age levels. Especially in the early childhood years, the majority of toys involved enactive modes of interaction. For example, stacking blocks, push toys, balls, climbers, riding vehicles, and other toys for young children usually required the child to engage in many physical actions. Toys for older children also often encouraged motoric interactions. Elementary-age children used jump ropes, skates, climbers, bikes, and other toys requiring enactive responses. Iconic experiences were also common at later ages, with child use of dolls and action figures who engaged in child-enacted pretense scripts, and there were many toy props that encouraged pretend and language exploration. This pretense often involved symbolic modes as well, as language and writing were used to further the play scripts and the scenarios developed were often complex or of long duration. Thus, in play with traditional toys children would have had many opportunities to gain rich levels of cognitive understanding both through their initially physically enactive play and then later being engaged in play that involved iconic and symbolic levels of understanding. Play that embodied physical and motoric experiences provided the undergirding and visceral levels of understanding for the other representation modes. Also, many traditional modes of children’s play provided integrated experiences that included enactive, iconic, and symbolic levels.

Toys available to most children usually had high transparency because some toys were made by the child or a family member and resembled the activities in which the family engaged. For example, if a child made a dog from sticks, straw, and discarded cloth, the toy would be highly transparent because the qualities, components, and composition of the dog would be determined by the child. These types of toys, created by younger and older children based on their imaginations, would have high transparency because they were self-made. Manufactured toys and toys available to children from wealthier families would have high transparency if based on commonly available objects in the environment because they usually were simple enough for the child to understand the form and functions of the toy. Similarly, a manufactured wood-carved or cloth-sewed toy dog would still have high transparency because the child would be familiar with the qualities of a dog. Although the toy dog was not self-made, it would still be high in terms of transparency since the child would have had many experiences with real-world examples.

The challenge of such toys could be increased by the child simply adding or removing parts or accessories. The dog made from sticks, straw, and discarded cloth or the wooden or cloth manufactured dog toy might, on another day, be transformed by the child into a horse or some other animal. The nonprecise nature of the self-made toy would enable the child to make the toy to be anything that vaguely resembles a four-footed animal. A more exquisitely wood-carved dog, however, might have lower challenge because its precision would dictate its identity as a dog. Still, it could be many types of dog and the child also might imagine it to be a horse or other animal, but it is more likely that the child would stay with the manufacturer’s toy label. In the case of both the child-made and the manufactured dogs, however, the child could make changes such as adding some wings made of leaves, and then imagine the toy to be a flying animal. For less defined manufactured toys, such as blocks, children always could play at many levels of challenge. This is one reason that blocks have been such a long-lasting favorite with children because they could be used in many ways.

The accessibility of early toys might vary because children could play alone or with others and many toys, such as balls, were enhanced by group participation. The self-made and manufactured dogs, for example, might be played with alone but could also be part of a pretend world designed by siblings or friends, in which that toy interacted with others. Games with balls usually would have high accessibility, allowing a number of children to play simultaneously. Throwing a ball at a target bottle might involve turn-taking or developing rules for a more elaborate game. Ball play usually has high accessibility because it readily lends itself to group play. Other toys, for example board games, required multiple participants and thus they also had high accessibility. Thus, in general many early toys had the quality of high accessibility because they required multiple participants by virtue of their nature and design. Even if multiple participants were not required, the option to play with others while using the toy was entirely the child’s choice. A jump rope is another example of a toy that has high accessibility although there is an individual element to its use. In this case, the individual can play alone and keep score by counting the number of consecutive jumps. Group play is also possible and it may be turn-based, such as a competition to see who can make the most consecutive jumps, or it can involve everyone with two individuals swinging the rope and the other children taking turns jumping.

In the 21st century, these affordance possibilities are still evident in non-technology-augmented toys. Such toys that have withstood the test of time—for example, the jump rope and wooden blocks—still have the same affordances as they did hundreds of years ago. Their purpose is transparent, they can be used simply or in complex ways, and they promote individual or group play. Similar to earlier times, however, there are significant differences between toys depending on their cost. More expensive toys are usually more complex, highly refined, and generally have more features and accessories. Whether these accessories and features promote transparency, challenge, and accessibility, however, or restrain some of these play opportunities is a question of interest.

For example, the initial design of toys such as Legos allowed children to create objects limited only by the child’s imagination. In terms of affordances, the basic blocks have high transparency because their shape dictates how they can be connected. They have very high challenge because they can be assembled into a variety of shapes with different implied functions. They also have high accessibility, because there is nothing inherent in the blocks that prevent group play. However, the affordances of these blocks change significantly when the blocks are designed for a specific purpose. For example, many of these blocks now come in kits that suggest they be assembled to a predetermined shape with predetermined functions. The child still could create other shapes, of course, but this requires overcoming the explicit message of the predetermined shape and structures that are “supposed” to be constructed. In this case, transparency remains high because the blocks contain all information necessary for their use. Challenge, however, is reduced because interaction with the toy is now limited to assembling the blocks into the predetermined state and then interacting with the finished produced in a manner consistent with the design. Accessibility remains somewhat the same, because there is nothing inherent in the toy that prevents the child from playing with others.

The examination of contexts of play in earlier times presents a picture that is very different from the context issues that have arisen with the advent of technology-augmented play objects. Play in earlier times usually involved contexts that would be identified as physical. During the mid-20th century, however, some virtual contexts began to be available. For example, programs heard on the radio sometimes encouraged some game-like play. Evaluation of play materials becomes more difficult when the virtual and mixed-reality contexts are considered. Although for young children, physical types of play materials continue to predominate, because play objects and their features now have become so complex, it is sometimes difficult to separate the physical, virtual, and mixed conditions. Many present-day technology-augmented play materials had origins in early play objects such as doll figures, transportation vehicles, and construction materials, but their virtual capabilities have increased tremendously over the past few years. With the advent of video games and online play environments in the late 20th century, the distinctions among these context differences are more difficult to separate because they reflect the reality of present-day mixed-reality play.

Play materials in the past clearly were differentiated in regard to their representation modes, their affordances, and their contexts. However, there have been many changes in the play environment, especially in the last 50 years, and the substance of the representation modes, affordance characteristics, and context environments have changed as well. The current trends in play that are increasing the pervasiveness and complexity of technology-augmentation in both traditional and innovative play materials appear to be changing the landscape of play for both children and adolescents. Whether these differences in the play experiences of children and adolescents will result in differences in brain development and subsequently in social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development is presently only at the level of speculation. However, since play often provides the environment for growth in these other developmental areas, this question is an important one to consider.

FIGURE 2.11 The snow is fun to play in!

FIGURE 2.12 We’re driving like dad does.

FIGURE 2.13 See me make a splash in the pool!

FIGURE 2.14 I am learning to ride my new bike.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2001). Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics, 107(2), 423.

American Academy of Pediatrics (2013). Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics, 132(5), 958–961.

Bergen, D. (2003, November). College students’ memories of their childhood play: A ten year comparison. Paper presentation at the annual conference of the National Association for the Education of Young Children, Chicago.

Bergen, D., Liu, W., & Liu, G. (1997). Chinese and American students’ memories of childhood play: A comparison. International Journal of Educology, 1(2), 109–127.

Bergen, D., & Williams, E. (2008). Differing childhood play experiences of young adults compared to earlier young adult cohorts have implications for physical, social, and academic development. Poster presentation at the annual meeting of the Association for Psychological Science, Chicago, IL.

Bruner, J. S. (1964). The course of cognitive growth. American Psychologist, 19(1), 1–15.

Burbules, N. C. (2006). Rethinking the virtual. In J. Weiss, J. Nolan, J. Hunsinger, & P. Trifonas (Eds.), The international handbook of virtual learning environments (Vol. 1, pp. 37–58). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Carr, M. (2000). Technological affordances, social practice and learning narratives in an early childhood setting. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 10, 61–79.

Davis, D., & Bergen, D. (2014). Relationships among play behaviors reported by college students and their responses to moral issues: A pilot study. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28, 484–498.

Davis, D., & Bergen, D. (2015). College students’ technology-related play reports show differing gender and age patterns. Poster presentation at the Association for Psychological Science, New York.

Dey, A. K. (2001). Understanding and using context. Human-Computer Interaction Institute. Paper 34. http://repository.cmu.edu/hcii/34

Dey, A. K., Abowd, G. D., & Salber, D. (2001). A conceptual framework and a toolkit for supporting the rapid prototyping of context-aware applications. Human-Computer Interaction, 16, 97–166.

Erdogan, N., Corlu, M. S., & Capraro, R. M. (2013). Defining innovation literacy: Do robotics programs help students develop innovation literacy skills? International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(1), 1–9.

Gardner, H., & Davis, K. (2013). The app generation: How today’s youth navigate identity, intimacy, and imagination in a digital world. Yale University Press.

Gibson, E. J. (1969). Principles of perceptual learning and development. New York: Appleton- Century-Crofts.

Goldstein, J. H. (2013). Technology and play. Scholarpedia, 8(2), 304–334.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. MIT Press.

Kafai, Y. (2006). Play and technology: Revised realities and potential perspectives. In D. P. Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.), Play from birth to twelve: Contexts, perspectives, and meanings (2nd ed., pp. 207–214). New York: Routledge.

Kahn, P. H., Friedman, B., Perez-Granados, D. R., & Freier, N. G. (2004). Robotic pets in the lives of preschool children. Paper presented at CHI, Vienna, Austria, April.

Kang, C. (2013, December 10). Infant iPad seats raise concerns about screen time for babies. http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/fisher-prices-infant-ipad-seat-raises-concerns-about-baby-screen-time/2013/12/10/6ebba48e-61bb-11e3-94ad-004fefa61ee6_story.html

Katzer, C., Fetchenhauer, D., & Belschak, F. (2009). Cyberbullying: Who are the victims?: A comparison of victimization in internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 21(1), 25.

Klahr, D., Triona, L. M., & Williams, C. (2007). Hands on what? The relative effectiveness of physical versus virtual materials in an engineering design project by middle school children. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(1), 183–203.

Levin, D. (2013). Beyond remote-controlled childhood: Teaching young children in the media age. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Lim, S. S., & Clark, L. S. (2010). Virtual worlds as a site of convergence for children’s play. Journal For Virtual Worlds Research, 3(2), 1–19.

Marsh, J. (2010). Young children’s play in online virtual worlds. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(1), 23–39.

Milgram, P., & Kishino, F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Information and Systems, 77(12), 1321–1329.

Offermans, S., & Hu, J. (2013). Augmenting a virtual world game in a physical environment. Journal of Man, Machine and Technology, 2(1), 54–62.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms. Brighton, MA: Harvester.

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4(2), 148–169.

Plowman, L., Stevenson, O., Stephen, C., & McPake, J. (2012). Preschool children’s learning with technology at home. Computers & Education, 59(1), 30–37.

Resnick, L. B. (1994). Situated rationalism: Biological and social preparation for learning. In L. A. Hirschfeld & S. A. Gelman (Eds.), Mapping the mind. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge.

Wartella, E., Caplovitz, A. G., & Lee, J. H. (2004). From Baby Einstein to Leapfrog, from Doom to the Sims, from instant messaging to internet chat rooms: Public interest in the role of interactive media in children’s lives. Social Policy Report, 28(4), 1–19.

Weigel, D.J., Martin, S.S., & Bennett, K. K. (2010). Pathways to literacy: Connections between family assets and preschool children’s emergent literacy skills. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(1), 5–22.