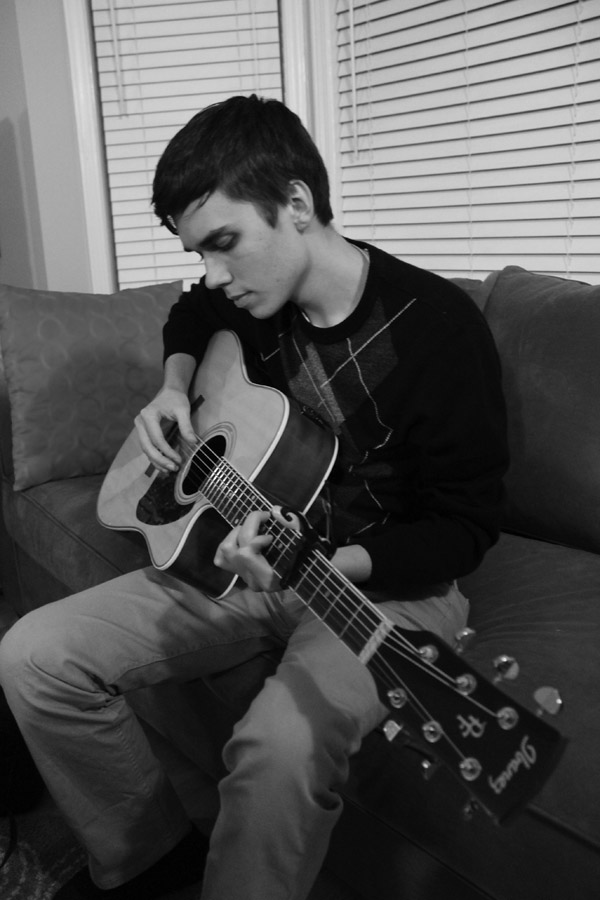

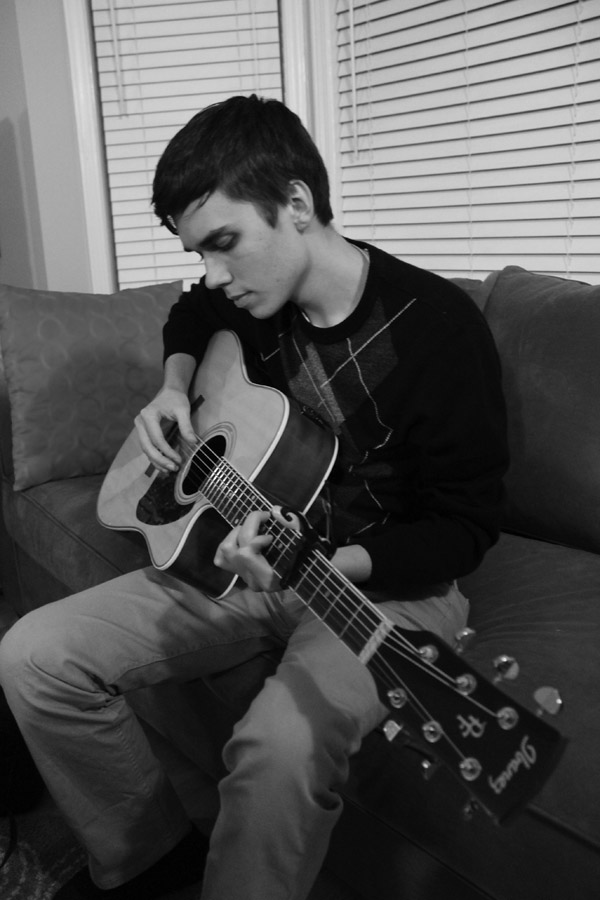

FIGURE 6.1 I like to create my own songs.

Professor Challenge accepted a buyout from Middle Country University even though she really was not ready to retire. However, her department courses now are all online and the university has decided that it is more cost effective just to keep the clinical faculty to maintain classes and interact online with students. Her husband, Professor Smarter, retired earlier when the Philosophy Department was reconceptualized into the Department of Technological Thought. Both parents are now wondering what is the best way to prepare their children, Blaine (age 4), Olivia (age 9), and Granson (age 15) to meet the employment and personal challenges of the future. They are aware that Blaine spends most play time in pretend activities with his talk/action figures or with animals that he has made from sticks and stones found in their yard. Olivia’s play activities concern them because they involve extensive time in online communication with friends. She spends much time in her room since all of her schoolwork is also online. Granson primarily plays violent games online, but he also spends time hiking in the woods near their house and doing “extreme” sports with friends.

It is very difficult to make definitive recommendations about what the play of children and adolescents should be like and what the range of such play should incorporate given the present state of technology and the uncertainty of the future. Further complicating the issue is the fact that there are many diverging perspectives on what ought to happen and what should be the goals for society. These varied perspectives and the future predictions derived from those perspectives must be recognized as important because they will guide today’s decisions that subsequently lay the groundwork for tomorrow’s reality. The risks involved in encouraging certain types of play experiences rather than others is that if the encouraged behaviors are too narrow, parents and educators may be preparing young individuals for a society that will not exist. If they are too broad, however, then they may be so diffuse that they become meaningless. Nevertheless, the process of prediction and recommendation must occur because children of the future will be shaped by their play experiences just as children in the past were influenced by their play experiences. The play of infants, toddlers, and young children will clearly affect their brain development, as well as their social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development, and the play of older children and adolescents will be an important factor in promoting the refinement and strengthening of brain capabilities. Because the dynamic system interactions between play experiences and brain development are crucial elements for human survival and evolutionary success, preparing children for the future must involve attention to these issues.

One place to start is by determining the qualities that will benefit individuals despite whatever the future brings. Two such qualities are versatility and resilience. Versatile individuals can more easily adapt to future realities, and resilient individuals have the fortitude to recover from adversities. The important question thus becomes “How do we help foster versatility and resilience in younger individuals?” There are many ways to foster versatility and resilience but one of the most obvious ways is through their play. In particular, if during each age period of life, individuals have rich play experiences of all types, both traditional and technology-augmented, then the development of these characteristics will be greatly enhanced.

Playfulness is an advantage that human beings have in abundance and there is ample evidence of the evolutionary advantages of playfulness (Ellis, 1998; Smith, 2007). Combined with the human capacity for adaptation, it can be argued that effective forms of versatility and resilience could develop both from general, nonspecific, play-related sources and from specifically designed play environments and materials of both non-technology and technology-augmented types. To encourage experiences that will prepare the next generations to have the versatility and resilience that they will need to meet ever-changing future environments, parents, educators, toy manufacturers, virtual game and online play designers, and interested adults in the community should all be aware of the changing play environment and try to promote a rich range of play experiences that will foster optimum brain development and effective adaptation to the world of the future.

Although the exact nature of the future world that humans will experience is unknown, one key to effective survival is through promoting the developmentally appropriate practices that parents and educators have promoted in the past while also supporting the expansion of abilities that may be required in the future. Effective social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development will continue to rely on the versatility and resilience gained in play experiences during childhood and adolescence.

Because of the rapidity of change in technology-augmented play and the potential interplay of this dynamic system with the dynamic systems of play development and brain maturation, it is not possible to give definitive short-term or long-term guidelines for how best to preserve the important qualities gained from play experiences. However, everyone who has responsibility for the future development of young children, older children, and adolescents can keep in mind the dynamic system factors that may interact to affect how well they are being prepared for their future. A review of some of these factors can give guidance for both practice and policy.

There are a number of the qualities of dynamic systems that must be kept in mind when planning and encouraging developmentally rich play experiences (Thelen & Smith, 1994). As noted earlier, such systems are:

Researchers already have used the dynamic systems model to study dyadic play (Steenbeck & van Geert, 2005) and have shown that self-organizing components of play systems change over time and follow many tenets of dynamic systems theory. For example, in a recent study of collaborative play, in which the dyadic interactions of the players were the variable of interest (Steenbeek, van der Aalsvoort, van Geert, 2014), the researchers found male and female differences in dyadic changes in the play system over time. They state that the purpose of such studies is “to try to understand the underlying dynamics of the play process by building a simulation model of these dynamics” (pp. 271–272). Similar studies involving children’s social play with technology-augmented play materials are needed. As research techniques that draw on dynamic systems theory become more common in psychological and educational research, the many technological factors that are interacting to affect the dynamic system of the play and learning environment of the future may be more clearly identified. Until that is done, however, at least this dynamic perspective can be used to make recommendations for toy developers and marketers, digital game developers, online play environment designers, and community stakeholders, as well as for parents and educators.

It is important for adults who design and market toys, especially those with technology-augmented components to be aware of the dynamic system issues that are relevant for brain maturation and play development. In a recent chapter on emerging technology and toy design, Kudrowitz (2014) discusses the essentials of both technology-augmented and traditional types of toy design. First, he makes the distinction between a toy and a toy product. He says that toys can be any object, such as a spoon, that is played with but that “A toy product is an item that is intentionally designed for the primary purpose of play” (p. 237). He explains that those who design toys have special marketing problems. Toys must be innovative, robust, and relatively low cost and should appeal both to the children who will play with them and to the adults who will buy them. This market changes quickly and toy designers often do not have access to the most recently emerging technology. He suggests that toy designers need to think ahead to see how they will incorporate the newer technology into toys after it has been available in other products for some period of time. One of the ways that new technology is incorporated is by “wrapping” it around existing toys. For example, a software app might be downloaded to make a toy product be used in a new way or it may be controlled with a smartphone. Kudrowitz states that of the top 100 toys that sold in 2010, only about 10 of them had electronic components. As tablets and smart phones become typical playthings, however, he notes that the concept of a toy is changing. His advice to toy designers is to “make the toy about the play not about the technology. The play that the toy affords should be timeless” (p. 252).

There are some designers of technology-augmented play materials who try to embed the qualities of rich representation modes and affordances into their devices and games. For example, in Resnick’s (2006) discussion of the creative possibilities of such play, he describes technology-augmented computer play that encourages creative designing by children. Another set of designers, Lund and colleagues (Lund, Klitbo, & Jessen, 2005; Lund & Marti, 2009) have addressed the enactive mode issue by developing Playware, which is a set of robotic building blocks that children move on and experience balancing from the feedback of the motion. The blocks are “intelligent” in that they are flexible and adaptive depending on children’s movements. They state that those who design play materials for playgrounds should “adopt a design principle that respects this body-brain interplay” (Lund, Klitbo, & Jessen, 2005, p. 167). Such designs result in “children moving, exchanging, experimenting, and having fun, regardless of their cognitive or physical ability levels” (p. 168). Others have involved children not just in responding to technology but in being engaged in designing it. One of the greatest advocates for this approach is Allison Druin (2009, 2010) who involves children as “co-designers” of new technology. For example, Druin and Hendler (2000) have described a robot design program for elementary-age children, in which the children create the robotic toys.

In a study of children’s play with “smart” plush toys that interfaced with computer programs, Luckin, Connolly, Plowman, and Airey (2003) found that children could master the varied interfaces between the two and did seek help when needed. However, they concluded that these types of toys “are not impressive as collaborative learning partners” (p. 1). In another discussion of “smart toys” Allen (2004) states that they have a few limitations at the present time. One limitation is that the “toys have no ability to learn, so they are bound to predefined actions and speech … [and] there is little evidence of haptic design” (p. 180). He recommends that more haptic experiences should be promoted by these toys because touch is a primary way that humans learn. In a review of a number of case studies of children’s play with smart toys, he states that designers of such toys must realize play is a more complex concept than many designers have realized. He gives a number of suggestions for improving these toys to make the interfaces more natural. Kafai (2006) suggests that technology-augmented toys should have possibilities for encouraging all types of play—practice, pretense, and games. These various aspects of play are especially relevant for the affordance of challenge because flexibility of response is a component of challenge. Thus, the more varieties of play promoted by the toy, the more likely the toy will engage children’s interest and motivation. In a discussion of learning through play, Anderson (2014) stresses the role of embodied cognition. He suggests that designers of technology-augmented play and learning devices should encourage playful interactions, support self-directed learning, allow for self-correction, and record and respond to data collected, but also that they should make learning tangible. He states, “nearly everything is experienced with and through our bodies … through physical interactions with the world around us and via our various senses … we should strive for manipulatives and environments that encourage embodied learning” (p. 131). Anderson gives some examples of such designs, including “Motion Math,” “Sifteo Cubes,” and “Game Desk,” all of which incorporate aspects of embodied cognition.

Some suggestions for toy developers and marketers are the following:

Most commercial digital games, excluding many open-source titles, are designed to make money and any realistic suggestion would need to account for the financial impact. If typical suggestions such as reducing violence in digital games were implemented, the result may not only affect how play is experienced, but there may be significant effects on other human facets of life, for example moral development. However, the issue of violence in games is very complex, having substantial financial and legal implications. Perhaps better suggestions for game developers and marketers should focus on the representation modes and affordances of these games, in an effort to make them “better” for children and young adults. “Better” in this case is not simply higher entertainment value, but a superior game would try to also attend to the player as a human being and the game itself as a useful play activity. Some games already have features that attend to the human player. For example the online game Guild Wars™ has a feature that informs the player about the amount of time spent playing in the current session, and after a certain amount of time, the system suggests that the player “take a break.” Features like this are separate from, for example, a game developer making a more comfortable controller so that players can play for a longer time.

Attending to the humanity of the player might lead game developers to put more focus on increasing the enactive mode of the game. That is, advances in virtual reality may allow game developers and marketers to see the benefits of building games that include more body movement. In terms of affordances, more emphasis could be placed on increasing challenge and accessibility. Game developers could design games that are less repetitive, requiring novel interaction from the user in an effort to increase challenge. Similarly, games could be designed to encourage more interaction with others, preferably real interaction with a shared physical space. There are games that already implement some of these suggestions such as some titles from the Wii system, but this is not the reality in most cases.

According to Lauwaert (2007), there are also some constraints on creativity and initiation of possibilities even in games such as SimCity™ (created by Will Wright), which was designed to be open to possibilities. Wright compared his game to play with railroad sets and dollhouses and considered it another form of toy. However, because it is “an airtight software system” (p. 207), the player must conform to the design of the game. The feedback mechanisms that are embedded in the game strongly shape the way players can use the game. Lauwaert suggests that this is one of the ways game play differs from play with construction toys or other playthings and notes that because game designers try to make the technology embedded in order to enable players to be immersed in the game rather than aware of the technology, this prevents the players from playing “out of the box.”

In a recent review of video game research, however, Eichenbaum, Bavelier, and Green (2014) describe results of game play that show enhancement of perceptual, attentional, and cognitive skills. Some of this research has focused on assisting children with disabilities and older adults with cognitive impairments. They assert, “video games are neither intrinsically good nor intrinsically bad. Instead, the nature of their impact depends upon what users make of them” (p. 67). They conclude that their review of this research suggests that video games can serve a good purpose, especially for children with disabilities. Kahn (1999, 2004) has reported on an interactive computer puzzles game called ToonTalk that acts as a tutor to teach children how to design programs. The puzzles gradually introduce programming constructs and techniques within a playful context. This author stresses that programming can be learned by both children and adults in a playful way by doing these puzzles.

Wolpaw et al. (2000), in a summary of an international meeting on brain-computer interface technology, have asserted that, in regard to games, “The affordances of the features in the game seem to be most important for the player” (p. 1). They question whether specific learning goals are met in games because it may be what the players really learn is “computer game literacy.” This view has some support from Linderoth, Lindström, and Alexandersson (2004), who videotaped elementary age children’s play with four games (a car building game, a hospital manager game, a noble family reputation building game, and an avatar battle game). They concluded that the children were able to design ways “to communicate the affordances of different game features to each other … [and] treated the game itself as an object of learning” (p. 164) rather than learning other concepts to apply outside of the game situation. In 2000, Chidambaram and Zigurs (2000) predicted that there were many games being developed for the internet and they pointed out that businesses were developing many online games that “take advantage of the Web’s unique nature for playing games and paying for them” (p. 145). Separating out the business motivations for offering games to children and adolescents from other motivational sources is not easy, and thus, designers of such games have a role to play in evaluating both the potentially positive and negative developmental effects of online game play.

In the light of the varied views held about digital games, suggestions for game designers include the following:

Similar to the suggestions for digital games, developers and marketers of online play environments should consider improving their products in terms of the enactive representations, and challenge and accessibility affordances. Recent developments in both augmented and virtual reality systems may help in terms of the enactive mode. One example of the shift to this mindset is the acquisition of Oculus VR, maker of the Oculus Rift Virtual Reality headset, by Facebook. While the purchase is more than likely a financial decision, the result may alter the future direction of product development because of the attention paid to the enactive mode. Recent developments in virtual reality systems may help in terms of the enactive mode. That is, those who manage Facebook may be searching for more and better ways to enrich social interaction online, and one solution is to engage more senses and thus integrate the “whole” user into the virtual experience. The new sensory-rich experience will add value in terms of the enactive mode, and also it makes much financial sense in that users may find the experience appealing and the increase in new members coupled with the retention of the old members will be financially beneficial to Facebook.

Increasing challenge is a primary goal of many online play environments. In most cases, developers and marketers seek to build systems where users have a wide variety of tasks and options. The aim is to prevent users from feeling that the system is repetitive or that there are too few options for interaction. Suggestions in this area would be to continue developing ways to increase the nonrepetitive interactions among users. Similarly, accessibility is a major focus of many online play environments, because the systems depend on users interacting, albeit not in the same physical space. Developers should continue finding ways to connect individuals and removing the barriers that prevent or limit communication. Aside from technical or technological challenges, every effort must be made to ensure equal participation by diverse groups to ensure maximum accessibility. For example, systems should be designed to eliminate biases, such as gender and ethnicity, and minimize the effects of the “inauthentic person” (Bergen & Davis, 2011), the latter being a primary concern in terms of the potential to create caustic environments that users then avoid.

Developers and marketers of online play environments could also pay more attention to the human person as they develop their systems. Granted, they benefit most when the individual is using their system for extended periods of time, but at some point the pervasiveness of the virtual world may begin to have negative consequences in the real world. At this point, the individual may be forced to withdraw from the service and the loss of membership may have financial consequences for the service. Ideally online play environments would seek to promote balance in their members. This is admittedly very difficult when there are many systems and each is vying for as much attention from the user as it can get. Without changes, however, the current deluge of Twitter Tweets, Facebook updates, and Instagram posts will likely increase to the point where it negatively affects users, who will begin to abandon at least a subset of these systems. As is the case with technology-augmented toys, some online game developers are attempting to incorporate features that promote positive child and adolescent development. For example, Hsu and Lu (2003) have discussed an online game experience (TAM) that is designed to provide “a flow experience” that encourages attention, curiosity, and intrinsic interest. They state that “designers should keep users in a flow state” (p. 863).

Those who are involved in the development and marketing of games are encouraged to be attentive to the pervasiveness of games and game mechanics. The interest in the beneficial aspects of game play for development and learning comes not only from the game developers, but also from educators. The attention, curiosity, and intrinsic interest that are part of this flow state is one aspect that makes game-based learning appealing. Van Eck (2006) describes this shift in perspective as “we have largely overcome the stigma that games are ‘play’ and thus the opposite of ‘work’ ” (p. 17). The connections between play and work are sometimes perceived in contradictory terms. In reviewing responses from a survey that was part of the Pew Internet and American Life project, Anderson and Rainie (2012) describe both positive and negative perceptions of using game mechanics to drive action for various purposes. Positive perceptions included the belief that “gamification will be an increasingly common aspect of everyday digital activities” (p. 3). Negative perceptions reported concerned the ongoing trend of gamification as being possibly “used for behavioral manipulation” (p. 5). The degree to which game concepts can be co-opted for specific purposes are innumerable and include those that appear to have altruistic purposes, such as the gamified educational endeavors of Khan Academy, or those that have recruiting purposes such as the games developed as a military recruiting tool for the U.S. Army (http://www.americasarmy.com/). Although these two examples are overt in their purposes, it is also possible that other games are either intentionally or unintentionally developed with less overt purposes.

In many cases, online games inherently facilitate the formation of virtual communities, which encourages social interaction within the virtual environment. Real-world concepts such as “social capital” appear to exist within this space, for example Steinkuehler and Williams (2006) argued that massively multiplayer online games (MMO) “are new (albeit virtual) ‘third places’ for informal sociability that are particularly well suited to the formation of bridging social capital” (p. 903). While these concepts seem inherent to the medium, developers could pay special attention to designing systems that either enable or enhance a game’s ability to act as a beneficial social tool. Such actions would be fully supported by research examining the social aims that online games can serve. To that end, Trepte et al. (2012) recommended that there should be ways for encouraging “physical and social proximity as well as familiarity in gaming” (p. 838). They state that this is one way to increase “social capital” and lessen “the potential negative effects of online gaming by transforming games into an activity with a positive potential for offline friendships” (p. 838).

A recent study by the Pew Research Center (Hampton et al., 2014) investigated the concern that intensive social media interaction may lead to stress. These researchers reported that users did not report more stress due to time spent on these sites but did seem to find stressful much of the information that was communicated on the site. No matter which media they used (e.g., Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), the high users were more aware of stressful events occurring to friends or family. In particular younger users and females were more likely to report awareness of stressful events in the lives of their contacts. Thus, the researchers concluded that high stress levels were not directly the result of the media use but were related to the messages that users were receiving. Because of the less subtle messages that younger children and adolescents may send on these media, it may be that their stress from use may be greater. The reports of bullying would suggest that the overt stressful messages can be harmful; however, more research is needed before definite conclusions about stress relationships to these media can be confirmed. In any event, the “playfulness” of some of these media may be questionable.

Thus, suggestions for marketers of online play environments include the following:

The future of play and the future of humans in the larger society are not just issues for parents, educators, toy product designers, or digital game and online play environment designers. They are crucial issues for many other stakeholders as well. For example, these activities raise issues for corporate entities, community organizations, government policy makers, and cultural values proponents. In particular organizations concerned about child and adolescent media use such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (2013) have made policy statements regarding the amount of time that children of various ages should be involved with technology-augmented devices. Another organization, the National Association for Education of Young Children, which focuses on issues related to children from birth to age 8, has a position statement done in collaboration with the Fred Rogers Center that conveys their advice about technology-augmented play experiences. For example, they suggest that, because children use technology in ways that are similar to their other play experiences, “young children need opportunities to explore technology and interactive media in playful and creative ways” (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center, 2012, p. 7).

Most of the questions about how various types of technology-augmented play will influence future society have not even been identified, much less discussed in depth. Nevertheless, there are many questions about extremes in technology-augmented play that may have future societal implications. For example, hacking digital and online games is generally perceived as an example of playfulness with minimum consequences, but the hacking of corporation or government sites differs in moral quality. Similarly, designing a playful program that engages many young people online may have no lasting societal implications while designing a playful program containing racial, gender, sexual, or religious biases that may be harmful to others is questionable. Sutton-Smith (1998) has written about the “out of bounds” types of play that also are part of human experience but that have no educational or developmental benefits although they may be approved as “festive” parts of a particular culture. These extreme types of playful behaviors do not foster the social, emotional, moral, or cognitive development of children and adolescents. Concern about technology and its effect on development has been voiced by many organizations; for example, a Centers for Disease Control whitepaper by Kachur et al. (2013) outlines concerns and presents suggestions regarding adolescents, technology, and sexual health. Levin (2013) suggests working at the societal level for appropriate laws and policies and at the educational level for media literacy education.

Because of the wide-ranging and pervasive influence of technology-augmented play materials, the potential for harm from technology-augmented out-of-bounds play is great, and therefore, unanticipated effects of this type of play should be monitored by community stakeholders and policies should be designed to address such issues.

Thus, suggestions for community stakeholders include the following:

Although all of the stakeholders previously discussed have a role to play in ensuring that the social, emotional, moral, and cognitive developmental effects of technology-augmented play materials are positively focused, there will continue to be problematic issues that must be addressed by parents and educators. Because they are most aware of the possibilities of dynamic system interactions, ultimately, their role in protecting the experiences that will result in optimal brain maturation and enriching playful experiences for young children, older children, and adolescents also will depend on their encouragement of play that leads to versatility and resilience for future generations. How parents should guide their children’s use of internet resources is a problem throughout the world, as a study of this issue in Jordan indicates (Ihmeideh & Shawareb, 2014). These researchers found that parents with authoritative (as compared to authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful) parenting styles did act in ways that predicted how their children used the internet. They suggest that parenting programs, school policies, and the designers of media should collaborate to assist parents in knowing how to manage their children’s pervasive internet use. Robb and Lauricella (2014) also have advice for educators about their use of technology-augmented devices in the classroom and this advice is good advice for parents. They state that decisions about what devices to make available to children should be based on the “developmental level, interests, abilities, linguistic background, and needs of the children in their care” (p. 81).

One of the best ways for parents and educators to know what is most important in regard to young children’s play is to recall the types of play that they found most enjoyable when they were children. Often the most important characteristics adults remember about their play are the powerful feeling of control over their own experiences (i.e., being “in charge”) and the challenges they met by creatively affecting their play environment (i.e., exploring possibilities). No matter what type of play materials are involved, the best play gives young persons a feeling of control over their world. At later ages, this feeling can translate into versatile thinking in the face of problems and resilient responses to solving such problems. While there are many ways that rich play experiences for infants and young children can be promoted by parents and educators, here are a few of the most useful suggestions:

As the young person’s world expands, parents and teachers should signal their confidence in the versatility and resilience that the children have gained through their earlier elaborated play experiences. They should state that they expect responsible decision making about the amount of time devoted to technology-augmented play in relation to other types of play activity and give the support that is needed to assure that some balance is maintained.

Suggestions for this age level include:

One of the best ways to assure that young people gain versatility and resilience from their play is by having adults in their environment who value play and have a playful attitude throughout life.

Thus, this suggestion:

In a wide-ranging book called The Future of Mind, Kaku (2014) discusses the “evolving” brain, the development of the “artificial” mind (i.e., computer mind) and the very wide range of possible futures the human race may encounter. He is open to all of these possibilities but after reviewing the potentially amazing and useful as well as the problematic changes that may occur, he concludes by saying, “it is up to us to adopt a new vision of the future that incorporates all the best ideas. To me, the ultimate source of wisdom in this respect comes from vigorous democratic debate” (p. 322).

Play is a basic part of the human experience and it will continue to be exhibited in many forms for many generations to come. Because of the rapidity of technological change, it is not possible to predict what the playthings of the future will be. For those who are concerned about optimum child and adolescent brain, social, emotional, moral, and cognitive development, however, the challenge will be to keep in mind the important features of play that have contributed to human evolutionary progress and to evaluate changing technology-augmented play within the perspectives that have been discussed. There is no question that playful humans who maintain their versatility and resilience throughout life will be able to find fulfillment in the future, whatever that may be. Thus, it is important to engage in the debate and make the future human-technology interface a playful and life-enhancing process!

FIGURE 6.1 I like to create my own songs.

Figure 6.2 My practice play for the real ball game is important.

FIGURE 6.3 I’m immersed in my reading world.

FIGURE 6.4 Having fun with puppy play and music play.

Allen, M. (2004). Tangible interfaces in smart toys. In J. Goldstein, D. Buckingham, G. Brougere (Eds.), Toys, games, and media (pp. 179–194). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2013). Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics, 132(5), 958–961.

Anderson, J., & Rainie, L. (2012). The future of gamification. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/05/18/the-future-of-gamification/

Anderson, S. P. (2014). Learning and thinking with things. In J. Follett (Ed.), Designing for emerging technologies; UX for genomics, robotics, and the internet of things (pp. 112–138). Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Bergen, D., & Davis, D. (2011). Influences of technology-related playful activity and thought on moral development. American Journal of Play, 4(1), 80–99.

Chidambaram, L. & Zigurs, I. (Eds.). (2000). Our virtual world: The transformation of work, play and life via technology. IGI Global.

Druin, A. (2009). Mobile technology for children: Designing for interaction and learning. Morgan Kaufmann.

Druin, A. (2010). Children as codesigners of new technologies: Valuing the imagination to transform what is possible. New Directions for Youth Development, 128, 35–43.

Druin, A., & Hendler, J. A. (Eds.). (2000). Robots for kids: exploring new technologies for learning. Morgan Kaufmann.

Eichenbaum, A., Bavelier, D., & Green, C. S. (2014). Video games: Play that can do serious good. American Journal of Play, 7(1), 50–69.

Ellis, M. J. (1998). Play and the origin of the species. In D. Bergen (Ed.), Readings from play as a learning medium (pp. 29–31). Olney, MD: ACEI.

Hampton, K. N., Rainie, L., Lu, W., Shin, I., & Purcell, K. (2014). Social media and the cost of caring. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/15/social-media-and-stress/

Hsu, C. & Lu, H. (2003). Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Information & Management, 41, 853–868.

Ihmeideh, F. M., & Shawareb, A. A. (2014). The association between internet parenting styles and children’s use of the internet at home. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28(4), 411–425.

Kachur, R., Mesnick, J., Liddon, N., Kapsimalis, C., Habel, M., David-Ferdon, C., … Schindelar, J. (2013). Adolescents, technology and reducing risk for HIV, STDs and pregnancy. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kafai, Y. (2006). Play and technology: Revised realities and potential perspectives. In D. P. Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.). Play from birth to twelve: Contexts, perspectives, and meanings (2nd ed., pp. 207–214). New York: Routledge.

Kahn, K. A. (1999). Computer game to teach programming. Proceedings of the National Educational Computing Conference.

Kahn, K. (2004). Toontalk-steps towards ideal computer-based learning environments. In M. Tokoro & L. Steels (Eds.), A learning zone of one’s own: Sharing representations and flow in collaborative learning environments (pp. 253–270). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Kaku, M. (2014). The future of the mind: The scientific quest to understand, enhance, and empower the mind. New York: Doubleday.

Kudrowitz, B. (2014). Emerging technology and toy design. In J. Follett (Ed.), Designing for emerging technologies; UX for genomics, robotics, and the internet of things (pp. 237–255). Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Lauwaert, M. (2007). Challenge everything: Construction play in Will Wright’s SIMCITY. Games and Culture, 2(194).

Levin, D. (2013). Beyond remote controlled childhood: Teaching young children in the media age. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Linderoth, J., Lindström, B., & Alexandersson, M. (2004). Learning with computer games. In J. Goldstein, D. Buckingham, G. Brougere (Eds.), Toys, games, and media (pp. 157–176). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Luckin, R., Connolly, D., Plowman, L., & Airey, S. (2003). Children’s interactions with interactive toy technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(1), 1–12.

Lund, H. H., Klitbo, T., & Jessen, C. (2005). Playware technology for physically activating play. Artificial life and Robotics, 9(4), 165–174.

Lund, H. H., & Marti, P. (2009). Designing modular robotic playware. Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 2009. RO-MAN 2009. The 18th IEEE International Symposium (pp. 115–121).

National Association for the Education of Young Children & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College. (2012). Technology and interactive media as tools in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. Washington, DC: NAEYC; Latrobe, PA: Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College.

Resnick, M. (2006). Computer as paintbush: Technology, play, and the creative society. In Singer, D. G., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (Eds.), Play = Learning: How play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

Robb, M. B., & Lauricella, A. R. (2014). Connecting child development and technology: What we know and what it means. In C. Donohue (Ed.), Technology and digital media in the early years: Tools for teaching and learning (pp. 70–85). Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Smith, P. K. (2007). Evolutionary foundations and functions of play: An overview. In A. Goncu & S. Gaskins (Eds.), Play and development: Evolutionary, sociocultural, and functional perspectives (pp. 21–49). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Steenbeek, H., van der Aalsvoort, D., & van Geert, P. (2014). Collaborative play in young children as a complex dynamic system: Revealing gender related differences. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 18(3), 251–276.

Steenbeek, H., & van Geert, P. (2005). A dynamic systems model of dyadic interaction during play of two children. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2, 105–145.

Steinkuehler, C. A., & Williams, D. (2006). Where everybody knows your (screen) name: Online games as “Third Places.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(4), 885–909.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1998). The struggle between sacred play and festive play. In D. Bergen (Ed.), Readings from play as a medium for learning and development (pp. 32–34). Olney, MD: ACEI.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. Boston: MIT Press.

Trepte, S., Reinecke, L., & Juechems, K. (2012). The social side of gaming: How playing online computer games creates online and offline social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 832–839.

Van Eck, R. (2006). Game-based learning: It’s not just the digital natives who are restless. EDUCAUSE Review, 41(4), 16–30.

Wolpaw, J. R., Birbaumer, N., Heetderks, W. J., McFarland, D. J. McFarland, Hunter Peckham, P., … Vaughan, T. M. (2000). Brain-computer interface technology: A review of the first international meeting. IEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering, 8(2), 164–173.