12

Order Imbalances and Stock Price Movements on October 19 and 20, 1987

THE VARIOUS OFFICIAL REPORTS on the October Crash all point to the breakdown of the linkage between the pricing of the future contract on the S&P 500 and the stocks making up that index.1 On October 19 and 20, 1987, the future contract often sold at substantial discounts from the cash index, when theoretically it should have been selling at a slight premium. The markets had become “delinked.”

On October 19, the S&P 500 dropped by more than twenty percent. On October 20, the S&P 500 initially rose and then fell off for the rest of the day to close with a small increase for the day. These two days provide an ideal laboratory in which to examine the adjustment of prices of individual stocks to major changes in market perceptions. In the turbulent market of these two days, one might reasonably assume that a reevaluation of the overall level of the market, and not information specific to individual firms, caused most of the price changes in individual securities.

If most of the new information arriving on the floor of the NYSE on these two days was related to the overall level of the market and not firmspecific effects, large differences among the returns of large diverse groups of stocks could be attributable to further breakdowns in the linkages within the market.2 Just as the extreme conditions of these two days resulted in a breakdown of the linkages between the future market and the cash market for stocks, there may well have been other breakdowns.

Since the S&P 500 index plays a crucial role in index-related trading,3 this study begins with a comparison of the return and volume characteristics of NYSE-listed stocks that are included in the S&P index with those that are not included. This comparison reveals substantial differences in the returns of these two groups. The S&P stocks declined roughly seven percentage points more than non-S&P stocks on October 19 and, in the opening hours of trading on October 20, recovered almost all of this loss. This pattern of returns is consistent with a breakdown in the linkage between the pricing of stocks in the S&P and those not in the S&P.

The study then proposes a measure of order imbalances. Over time, there is a strong relation between this measure and the aggregate returns of both S&P and non-S&P stocks. Cross-sectionally, there is also a significant relation between the order imbalance for an individual security and its concurrent return.

Finally, the analysis shows that those stocks that experienced the greatest losses in the last hour of trading on October 19 experienced the greatest gains in the first hour of trading on October 20. Since those stocks with the greatest losses on October 19 had the greatest order imbalances, this pattern of reversals is consistent with a breakdown of the linkages among the prices of individual securities.

The chapter is organized as follows. Section 12.1 presents a description of the data. Section 12.2 compares the return and volume characteristics of S&P and non-S&P stocks. Section 12.3 contains the analysis of order imbalances. The study concludes with Section 12.4.

12.1 Some Preliminaries

The primary data that this study uses are transaction prices, volume, and quotations for all stocks on the NewYork Stock Exchange for October 19 and 20. The source of these data is Bridge Data. The data base itself contains only trades and quotations from the NYSE.4 As such, the data differ somewhat from the trades reported on the Composite tape that includes activity on regional exchanges.5

12.1.1 The Source of the Data

In analyzing these data, it is useful to have an understanding of how Bridge Data obtains its data. For the purposes of this chapter, let us begin with the Market Data System of the NYSE. This system is an automated communication system that collects all new quotations and trading information for all activity on the floor of the NYSE.

One main input to this system is mark-sense cards that exchange employees complete and feed into optical card readers. In this non-automated process, there is always the possibility that some cards are processed out of sequence. We have no direct information on the potential magnitude of this problem; however, individuals familiar with this process have suggested to us that this problem is likely to be more pronounced in periods of heavy volume and particularlywith trades that do not directly involve the specialist. Also, when there is a simultaneous change in the quote and a trade based upon the new quote, there is the possibility that the trade will be reported before the new quote.

The Market Data System then transmits the quotation data to the Consolidated Quote System and the transaction data to the Consolidated Tape System, both operated by SIAC (Securities Industry Automation Corporation) . These two systems collect all the data from the NYSE and other markets. SIAC then transmits these quotes and transactions to outside vendors and to the floor of the NYSE through IGS (Information Generation System). Except for computer malfunctions, this process is almost instantaneous.

Up to this point, there are no time stamps on the transmitted data. Each vendor and IGS supply their own time stamps. Thus, if there are any delays in the transmission of prices by SIAC to vendors, the time stamps will be incorrect. Two vendors of importance to this study are Bridge Data and ADP. ADP calculates the S&P Composite Index, so that any errors or delays in prices transmitted by SIAC to ADP will affect the Index. Also, the time stamps supplied by Bridge Data may sometimes be incorrect.

According to the studies of the GAO and the SEC, there were on occasion substantial delays in the processing of the mark-sense cards on October 19 and 20. In addition, the SEC reports that SIAC experienced computer problems in transmitting transactions to outside vendors, with the result that there were no trades reported from 1:57 p.m. to 2:06 p.m. on October 19 and from 11:47 a.m. to 11:51 a.m. on October 20.6 According to an official at the NYSE, all trades that should have been transmitted during these two periods were sent to outside vendors as soon as possible after the computer problems were fixed.

There were no reported computer problems associated with the Consolidated Quote System, and outside vendors continued to receive and transmit changes in quotes during these two periods. Since an outside vendor uses the time at which it receives a quote or transaction as its time stamp, the time stamps for the quotes and transactions provided by all outside vendors are out of sequence during and slightly after these two periods. These errors in sequencing may introduce biases in our analyses of buying and selling pressure during these periods, a subject to be discussed below.

An analysis of the data from Bridge discloses that, in addition to these two time intervals, there were no trades reported from 3:41 p.m. to 3:43 p.m. on October 19 and from 3:44 p.m. to 3:45 p.m. on October 20. We do not know the reason for these gaps.

12.1.2 The Published Standard and Poor’s Index

The published Standard and Poor’s Composite Index is based upon 500 stocks. Of these 500 stocks, 462 have their primary market on the NYSE, eight have their primary market on the American Stock Exchange, and thirty are traded on NASDAQ.

The first step in calculating the index for a specific point in time is to multiply the number of shares of common stock outstanding of each company in the index by its stock price to obtain the stock’s market value. The number of shares outstanding comes from a publication of Standard and Poor’s (1987) 7 The share price that S&P uses is almost always the price of the last trade on the primary market, not a composite price.8

The next step is to sum these 500 market values, and the final step is to divide this sum by a scale factor. This factor is adjusted over time to neutralize the effect on the index of changes either in the composition of the index or in the number of shares outstanding for a particular company. S&P set the initial value of this scale factor so that the index value was “10.0 as of 1941–1943.”

Since this study had for the most part only access to NYSE prices, the subsequent analyses approximate the S&P index using only the 462 NYSE stocks. The market value of the thirty-eight non-NYSE stocks as of the close on October 16 equals only 0.3 percent of the total market value of the index, so that this approximation might be expected to be quite accurate. Indeed, some direct calculations and some of the subsequent analyses are consistent with this expectation. In one subsequent analysis, the 462 NYSE stocks are partitioned into four size quartiles of roughly an equal number of companies each, based upon market values on October 16. The largest quartile contains 116 companies with market values in excess of 4.6 billion; the second largest quartile contains 115 companies with market values between 2.2 and 4.6 billion; the third contains 116 companies with values between 1.0 billion and 2.2 billion; and the fourth contains 115 companies with market values between 65.4 million and 1.0 billion.

In comparisons of companies included in the S&P with companies not included in the S&P, we exclude the 178 non-S&P companies with market values of less than 65.4 million—the smallest company listed in the S&P.9After excluding these 178 companies, there remain 929 non-S&P companies for comparison purposes. These 929 companies are classified into size quartiles by the same break points as the quartiles of the S&P. This classification results in sixteen non-S&P companies with assets in excess of 4.6 billion, twenty-seven companies corresponding to the second largest quartile of S&P stocks, 100 companies for the next S&P quartile, and 786 companies for the smallest S&P quartile.

12.2 The Constructed Indexes

Indexes, such as the S&P 500, utilize the price of the last trade in calculating market values. In a rapidly changing market, some of these past prices may be stale and not reflect current conditions. This problem is particularly acute for stocks that have not yet opened, in which case the index is based upon the closing price of some prior day. As a result of such stale prices, the published S&P index may underestimate losses in a falling market and underestimate gains in a rising market. The Appendix describes an approach to mitigate these biases by constructing indexes that utilize only prices from stocks that have traded in the prior fifteen minutes. After the first hour and a half of trading each day, the analysis in the Appendix indicates that this approach virtually eliminates the bias from stale prices. There remains some bias in the first hour and a half of trading.

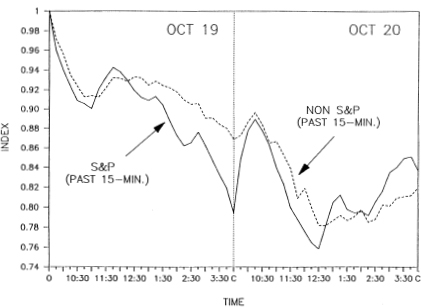

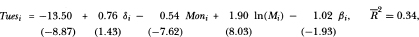

The comparison of the returns of the NYSE stocks included in the S&P Index with those not included utilizes two indexes—one for S&P stocks and one for non-S&P stocks. To minimize the bias associated with stale prices, both of these indexes utilize only prices of stocks that have traded in the prior fifteen minutes. The index for non-S&P stocks is value weighted in the same way as the constructed index for S&P stocks. Both of these indexes have been standardized to 1.0 as of the close of trading on October 16. To eliminate any confusion, we shall always refer to the index published by S&P as the published index. Without any qualifier, the term “S&P index” will refer to the calculated S&P index as shown in Figure 12.1.

There are substantial differences in the behavior of these two indexes on October 19 and 20. On Monday, October 19, the S&P index dropped 20.5 percent. By the morning of Tuesday, October 20, the S&P index had recaptured a significant portion of this loss. Thereafter, the S&P index fell but closed with a positive gain for the day. In contrast, the return on the non-S&P index was —13.1 on Monday and —5.5 percent on Tuesday.

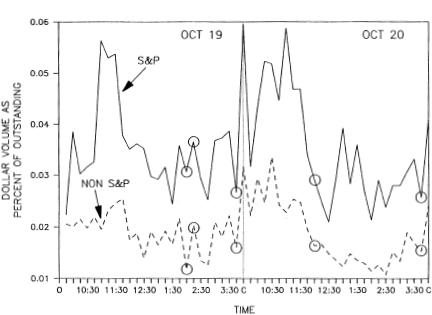

In addition, the relative trading volume in S&P stocks exceeded the relative trading volume in non-S&P stocks in every fifteen-minute interval on October 19 and 20 (Figure 12.2). The relative trading volume in S&P stocks is defined as the ratio of the total dollar value of trading in all S&P stocks in a fifteen-minute interval to the total market value of all S&P stocks, reexpressed as a percentage. The market values for each fifteen-minute interval are the closing market values on October 16, adjusted for general market movements to the beginning of each fifteen-minute interval.10 The relative trading volume in non-S&P stocks is similarly defined.

Of particular note, the recovery of the S&P stocks on Tuesday morning brought the S&P index almost in line with the non-S&P index. One possible interpretation of this recovery is that there was considerably greater selling pressure on S&P stocks on October 19 than on non-S&P stocks. This selling pressure pushed prices of S&P stocks down further than warranted, and the recovery in the opening prices of S&P stocks on October 20 corrected this unwarranted decline. The greater relative trading volume on S&P stocks is also consistent with this interpretation.

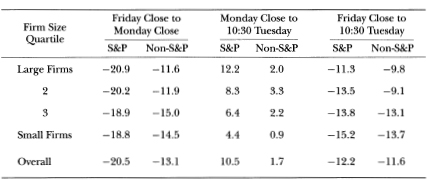

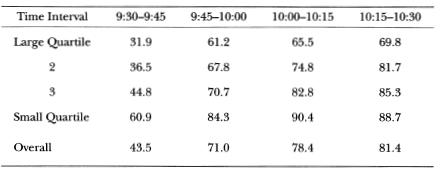

Before concluding this section, let us consider another explanation for the differences in the returns of the two indexes. The S&P index is weighted more heavily toward larger stocks than the non-S&P index, and it is possible that the differences in the returns on the two indexes may be due solely to a size effect. Although a size effect can explain some of the differences in the returns, it does not explain all of the differences. Results for indexes constructed using size quartiles are presented in Table 12.1. From Friday close to Monday close, indexes for any size quartile for S&P stocks declined more than the corresponding indexes for non-S&P stocks.11 There is no simple relation to size; for S&P stocks, the returns increase slightly with size, and, for non-S&P stocks, they decrease with size.

Figure 12.1. Comparison of price indexes for NYSE stocks included in the S&P 500 Index and not included for October 19 and 20, 1987. On these two dates, the S&P Index included thirty-eight non-NYSE stocks, which are not included in the index. There were 929 non-S&P stocks with market values equal to or greater than the smallest company in the S&P. The indexes themselves are calculated every fifteen minutes. Each value of the index is based upon all stocks that traded in the previous fifteen minutes. The market value of these stocks is estimated at two points in time. The first estimate is based upon the closing prices on October 16. The second estimate is based upon the latest trade price in the previous fifteen minutes. The ratio of the second estimate to the first estimate provides the values of the plotted indexes. The value of the plotted indexes at 9:30 on October 19 is set to one.

From Monday close to 10:30 on Tuesday, the returns on S&P stocks for any size quartile exceeded the returns for non-S&P stocks. Yet, unlike the Monday returns, there is a substantial size effect with the larger stocks, particularly those in the S&P index, displaying the greater returns. From Friday close to 10:30 on Tuesday, the losses on S&P stocks for any size quartile exceeded those on non-S&P stocks. There is a size effect with the smaller stocks realizing the greatest losses. Nonetheless, because of the differences in the weightings in the S&P and non-S&P indexes, the difference in the overall returns is only 0.6 percent.12

Figure 12.2. Plot of dollar volume in each fifteen-minute interval on October 19 and 20, 1987 as a percent of the market value of the stocks outstanding separately for S&P and non-S&P stocks. These plots exclude companies with less than 65.4 million dollars of outstanding stock as of the close on October 16. Market values for each fifteen-minute interval are the closing market values on October 16, adjusted for general market movements to the beginning of each fifteen-minute interval. The adjustment is made separately for each size quartile. The circled points represent time periods in which there were breakdowns in the reporting systems and thus may represent less reliable data.

Table 12.1. Percentage returns on S&P and non-S&P stocks cross-classified by firm size quartiles for three time intervals on October 19 and 20, 1987. The overall returns from Friday close to Monday close and from Friday close to 10:30 on Tuesday are taken from the index values plotted in Figure 12.1. The overall return from Monday close to 10:30 on Tuesday is derived from these two returns. The breakpoints for the size quartiles are based upon the S&P stocks and are determined so as to include approximately the same number of S&P stocks in each quartile. As a consequence, there are many more non-S&P stocks in the small firm quartile than in the large firm quartile. In a similar way to the overall index, the returns from Friday close for the size quartiles are calculated using only stocks that have traded in the previous fifteen minutes and valued at the last trade in that interval.

12.3 Buying and Selling Pressure

In the last section, a comparison of the indexes for S&P and non-S&P stocks indicates that the prices of S&P stocks declined 7.4 percentage points more than the prices of non-S&P stocks on October 19. By the morning of October 20, the prices of S&P stocks had bounced back nearly to the level of non-S&P stocks.

This greater decline in S&P stocks and subsequent reversal is consistent with the hypothesis that there was greater selling and trading pressure on S&P stocks than on non-S&P stock on Monday afternoon. However, it is also consistent with other hypotheses such as the presence of a specific factor related to S&P stocks alone. Such a factor might be related to index arbitrage.

This section begins with the definition of a statistic to measure buying and selling pressure or, in short, order imbalance. At the aggregate level, there is a strong correlation between this measure of order imbalance and the return on the index. At the security level, there is significant correlation between the order imbalance for individual securities and their returns. Finally, the chapter finds that those stocks that fell the most on October 19 experienced the greatest recovery on October 20. This finding applies to both S&P and non-S&P stocks.

12.3.1 A Measure of Order Imbalance

The measure of order imbalance that this study uses is the dollar volume at the ask price over an interval of time less the dollar volume at the bid price over the same interval. Implicit in this measure is the assumption that trades between the bid and the ask price generate neither buying nor selling pressure. A positive value for this measure indicates net buying pressure, and a negative value indicates net selling pressure.

In estimating this measure of order imbalance, it is important to keep in mind some of the limitations of the data available to this study. As already mentioned, the procedures for recording changes in quotations and for reporting transactions do not always guarantee that the time sequence of these records is correct. Sometimes, when there is a change in the quotes and an immediate transaction, the transaction is recorded before the change in the offer prices and sometimes after.13 Although orders matched in the crowd should be recorded immediately, they sometimes are not. Finally, there are outright errors.14

To cope with these potential problems, the estimate of the order imbalance uses the following algorithm: let t be the minute in which a transaction occurs.15 Let tp be the minute which contains the nearest prior quote. If the transaction price is between the bid and the ask of this prior quote, the transaction is treated as a cross and not included in the estimate of the order imbalance. If the transaction price is at the bid, the dollar value of the transaction is classified as a sale. If the price is at the ask, the dollar value of the transaction is classified as a buy. A quote that passes one of these three tests is termed a “matched” quote.

If the quote is not matched, the transaction price is then compared in reverse chronological order to prior quotations, if any, in tp to find a matched quote. If a matched quote is found, the quote is used to classify the trade as a buy, cross, or sell. If no matched quote is found, the quotes in minute t following the trade are examined in chronological order to find a matched quote to classify the trade. If no matched quote is found, the minute (tp — 1) is searched in reverse chronological order. If still no quote is found, the minute (t + 1) is searched. This process is repeated again and again until minutes (tp — 4) and (t + 4) are searched. If finally there are no matched quotes, the transaction is dropped.

On October 19, 82.8 percent of trades in terms of share volume16 match with the immediately previous quote, 9.5 percent with a following quote in minute t, and 6.2 percent with quotes in other minutes, leaving 1.5 percent of the trades unmatched. Of the matched trades, 40.7 percent in terms of share volume occurred within the bid and ask prices. The percentages for October 20 are 81.6 percent with the immediately previous quote, 12.3 percent with a following quote in minute t, 4.5 percent with other quotes, and 1.6 percent with no matched quotes. Finally, 42.4 percent of the matched trades occurred within the bid and ask prices.

This estimate of order imbalance obviously contains some measurement error, caused by misclassification.17 However, given the strong relation between this estimate of order imbalance and concurrent price movements, the measurement error does not obscure the relation. Nonetheless, in interpreting the following empirical results, the reader should bear in mind the potential biases that these measurement errors might introduce.

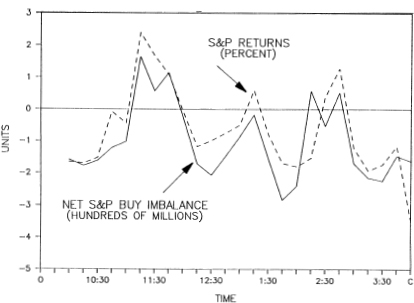

12.3.2 Time-Series Results

The analysis in this section examines the relation between fifteen-minute returns and aggregate order imbalances. As detailed in the Appendix, the estimates of fiteen-minute returns utilize only stocks that trade in two consecutive fifteen-minute periods. The actual estimate of the fifteen-minute return is the ratio of the aggregate market value of these stocks at the end of the fifteen-minute interval to the aggregate market value of these stocks at the end of the prior fifteen-minute interval, reexpressed as a percentage. The price used in calculating the market value is the mean of the bid and ask prices at the time of the last transaction in each interval.18 The aggregate order imbalance is the sum of the order imbalances of the individual securities within the fifteen-minute interval.

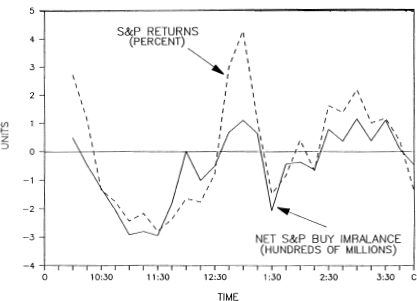

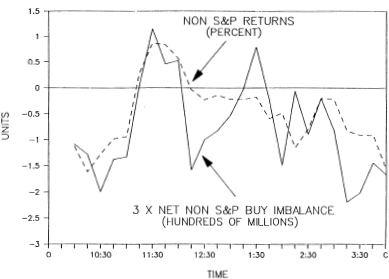

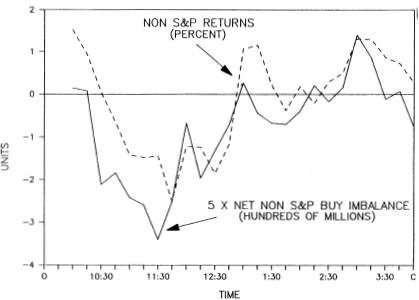

In the aggregate, there is a strong positive relation between the fifteen minute returns for the S&P stocks and the aggregate net buying and selling pressure (Figures 12.3 and 12.4). For October 19, the sample correlation is 0.81 and, for October 20, 0.86. The relations for non-S&P stocks are slightly weaker, with correlations of 0.81 and 0.72 (Figures 12.5 and 12.6). All four of these correlation coefficients are significant at usual levels.19

This positive relation is consistent with an inventory model in which specialists reduce their bid and ask prices when their inventories increase and raise these prices when their inventories decrease. This positive relation is also consistent with a cascade model in which an order imbalance leads to a price change and this price change in turn leads to further order imbalance, and so on. This positive relation by itself does not establish that there is a simple causal relation between order imbalances and price changes.

Figure 12.3. Plot of fifteen-minute returns on S&P stocks versus the order imbalance in S&P stocks in the same fifteen minutes for October 19, 1987. The fifteen-minute returns are derived from stocks that traded in the fifteen-minute interval and traded in the prior fifteen-minute interval. The fifteen-minute return itself is the ratio of the total value of these stocks in the interval to the total value in the prior fifteen-minute interval, reexpressed as a percentage. The price of each stock is taken as the mean of the bid and the ask price at the time of the last transaction in each interval. The first return is for the interval 9:45-10:00. The net S&P buy imbalance is the dollar value of the trades at the ask less the dollar value of the trades at the bid in the fifteen-minute interval. The correlation between the fifteen-minute returns and the order imbalance is 0.81.

12.3.3 Cross-Sectional Results

The aggregate time series analysis indicates a strong relation between order imbalances and stock returns. This finding, however, provides no guarantee that there will be any relation between the realized returns of individual securities and some measure of their order imbalances in any cross-section. In the extreme, if all trading is due to index-related strategies and these strategies buy or sell all stocks in the index in market proportions, all stocks will be subject to the same buying or selling pressure. As a result, there will be no differential effects in a cross-section.

Let us for a moment continue to assume that all trading is due to index related strategies, but let us assume that these strategies buy or sell subsets of the stocks in the index and not necessarily in market proportions. Even in this case, it is theoretically possible that there will be no cross-sectional relations if, for instance, all stocks are perfect substitutes at all times.

Figure 12.4. Plot of fifteen-minute returns on S&P stocks versus the order imbalance in the same fifteen minutes for October 20, 1987. The fifteen-minute returns are derived from stocks that traded in the fifteen-minute interval and traded in the prior fifteen-minute interval. The fifteen-minute return itself is the ratio of the total value of these stocks in the interval to the total value in the prior fifteen-minute interval, reexpressed as a percentage. The price of each stock is taken as the mean of the bid and the ask price at the time of the last transaction in each interval. The first return is for the interval 9:45-10:00. The net S&P buy imbalance is the dollar value of the trades at the ask less the dollar value of the trades at the bid in the fifteen-minute interval. The correlation between the fifteen-minute returns and the order imbalance is 0.86.

As a result, finding no relation between realized returns and order imbalances in a cross-section of securities does not preclude a time series relation. Finding a relation in a cross-section indicates that, in addition to any aggregate relation over time, the relative amount of order imbalance is related to individual returns.

With this preamble, let us turn to the cross-sectional analysis. To begin, the trading hours of October 19 and October 20 are divided into half-hour intervals. The sample for a given half hour includes all securities that traded in the fifteen minutes prior to the beginning of the interval and in the fifteen minutes prior to the end of the interval. For each security, the order imbalance includes all trades following the last trade in the prior fifteen minutes through and including the last trade in the half-hour interval. The return for each security is measured over the same interval as the trading imbalance using the mean of the bid and ask prices. To control for size, the order imbalance for each security is deflated by its market value as of October 16 to yield a normalized order imbalance.

Figure 12.5. Plot of fifteen-minute returns on non-S&P stocks versus the order imbalance in the same fifteen minutes for October 19, 1987. The fifteen-minute returns are derived from stocks that traded in the fifteen-minute interval and traded in the prior fifteen-minute interval. The fifteen-minute return itself is the ratio of the total value of these stocks in the interval to the total value in the prior fifteen-minute interval, reexpressed as a percentage. The price of each stock is taken as the mean of the bid and the ask price at the time of the last transaction in each interval. The first return is for the interval 9:45-10:00. The net non-S&P buy imbalance is the dollar value of the trades at the ask less the dollar value of the trades at the bid in the fifteen-minute interval. The correlation between the fifteen-minute returns and the order imbalance is 0.81.

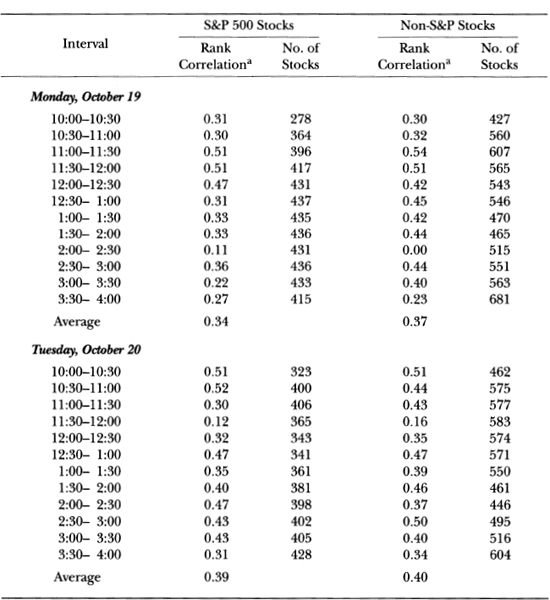

The estimated rank order correlation coefficients for the S&P stock are uniformly positive for the half-hour intervals on Monday and Tuesday (Table 12.2). They range from 0.11 to 0.51 and are statistically significant at the five percent level. The smallest estimate of 0.11 is for the 2:00 to 2:30 interval on Monday afternoon, during part of which the SIAC system was inoperable. All other estimates are above 0.20. The rank order correlation coefficients for the non-S&P stocks are similar to those for the S&P stocks. They range from 0.23 to 0.54, with the exception of the 2:00 to 2:30 interval on Monday. This analysis provides support for the hypothesis that there is a positive cross-sectional relation between the return and normalized order imbalance.

Table 12.2. Cross-sectional rank correlations of individual security returns and normalized order imbalance by half hour intervals. For a given half hour, a security is included if it trades in the fifteen minutes prior to the beginning of the interval and in the last fifteen minutes of the interval. The return is calculated using the mean of the bid and ask prices after the last transaction prior to the interval and the mean of the bid and ask prices at the end of the interval. Thus, there is a significant relation to order imbalances for S&P stocks, but not to order imbalances as measured here for non-S&P stock. Adding the Monday return to the S&P regression leads to a reduction in the z-statistic on scaled order imbalances to —0.92. As reported in footnote 23, the Monday returns enter significantly for both groups of stocks. This behavior of the regression statistics is consistent with the hypothesis that the scaled order imbalance measures selling pressure for individual securities with substantial measurement error and that the Monday return measures selling pressure with less error.

a The asymptotic standard error of the rank correlation estimates is  under the null hypothesis of zero correlation.

under the null hypothesis of zero correlation.

Figure 12.6. Plot of fifteen-minute returns on non-S&P stocks versus the order imbalance in the same fifteen minutes for October 20, 1987. The fifteen-minute returns are derived from stocks that traded in the fifteen-minute interval and traded in the prior fifteen-minute interval. The fifteen-minute return itself is the ratio of the total value of these stocks in the interval to the total value in the prior fifteen-minute interval, reexpressed as a percentage. The price of each stock is taken as the mean of the bid and the ask price at the time of the last transaction in each interval. The first return is for the interval 9:45-10:00. The net non-S&P buy imbalance is the dollar value of the trades at the ask less the dollar value of the trades at the bid in the fifteen-minute interval. The correlation between the fifteen-minute returns and the order imbalance is 0.72.

12.3.4 Return Reversals

The significant relation between order imbalances and realized returns leads to the conjecture that some of the price movement for a given stock during the periods of high order imbalance is temporary in nature. We might expect that, if negative order imbalances are associated with greater negative stock returns, the price will rebound once the imbalance is eliminated. If on Monday afternoon those securities exhibiting the greatest losses were subject to the greatest order imbalances, these securities should have the greatest rebounds on Tuesday if the imbalance is no longer there. This cross-sectional conjecture is the subject of this section.

The last hour of trading on October 19 and the first hour of trading on October 20 are considered in the analysis. For a stock to be included in the analysis, it had to trade on Monday between 2:45 and 3:00 and between 3:45 and the close of the market and had to open on Tuesday prior to 10:30.20The Monday return is calculated using the mean of the bid and ask prices for the last quote prior to 3:00 and the mean of the bid and ask prices for the closing quote. The Tuesday return is calculated using the mean of the bid and ask prices for Monday’s closing quote and the mean of the bid and ask prices for the opening quote Tuesday.21

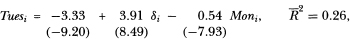

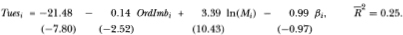

There are 795 stocks with both Monday and Tuesday returns as well as beta coefficients that will be used below. The cross-sectional regression of Tuesi, the Tuesday return for stock i, on the Moni, the Monday return, and δi, a dummy variable with the value of one for a stock in the S&P 500 and zero otherwise, is

where the numbers in parentheses are the associated heteroscedasticity consistent z-statistics.22 The positive estimated coefficient for the dummy variable reflects the previously observed greater aggregate drop and subsequent recovery in S&P stocks. The significantly negative coefficient on the Monday return is consistent with the conjecture of a reversal effect.23

Another explanation of this reversal pertains to a beta effect.24 If those stocks that fell the most on Monday had the greatest betas, these same stocks might exhibit the greatest returns on Tuesday, regardless of the level of order imbalances. Further, it is always possible that the reversal might be just a size effect. The following regression allows for the effects of these other two variables:

where Mi is the market value of stock i as of the close on October 16 and ßi is a beta coefficient estimated from the fifty-two weekly returns ending in September 1987 as described in footnote 12.25 The estimated coefficient on Monday’s return is virtually unchanged. The estimated coefficient on the dummy variable is no longer significant at the five percent level. Thus, in explaining the return during the first hour of trading on Tuesday, the distinction between S&P and non-S&P stocks becomes less important once one holds constant a stock’s market value and beta in addition to its return during the last hour on Monday.

These results are consistent with a price pressure hypothesis and lead to the conclusion that some of the largest declines for individual stocks on Monday afternoon were temporary in nature and can partially be attributed to the inability of the market structure to handle the large amount of selling volume.

12.4 Conclusion

The primary purpose of this chapter was to examine order imbalances and the returns of NYSE stocks on October 19 and 20,1987. The evidence shows that there are substantial differences in the returns realized by stocks that are included in the S&P Composite Index and those that are not. In the aggregate, the losses on S&P stocks on October 19 are much greater than the losses on non-S&P stocks. Importantly, by mid morning of October 20, the S&P stocks had recovered nearly to the level of the non-S&P stocks. Not surprisingly, the volume of trading in S&P stocks with size held constant exceeds the volume of trading in non-S&P stocks.

In the aggregate, there is a significant relation between the realized returns on S&P stocks in each fifteen-minute interval and a concurrent measure of buying and selling imbalance. Non-S&P stocks display a similar but weaker relation. Quite apart from this aggregate relation, the study finds a relation within half-hour intervals between the returns and the relative buying and selling imbalances of individual stocks. Finally, those stocks with the greatest losses in the afternoon of October 19 tended to realize the greatest gains in the morning of October 20.

These results are consistent with, but do not prove, the hypothesis that S&P stocks fell more than warranted on October 19 because the market was unable to absorb the extreme selling pressure on those stocks.26 If this hypothesis is correct, a portion of the losses on S&P stocks on October 19 is related to the magnitude of the trading volume and not real economic factors. A question of obvious policy relevance that this chapter has not addressed is whether buying and selling imbalances induced by index-related strategies have a differential relation to price movements from order imbalances induced by other strategies.

Appendix Al2

THIS APPENDIX DESCRIBES the procedures used in this chapter to construct both the levels and returns of various indexes. The evidence indicates that after the first hour and a half of trading on either October 19 or 20,1987, the biases from stale prices are minimal. To conserve space, we present detailed statistics only for the S&P index for October 19. The full analysis is available from the authors.

A12.1 Index Levels

To estimate index levels,27 we consider four alternative approaches. The first utilizes prices only of stocks that have traded in the past fifteen minutes. Every fifteen minutes, we estimate the return on the index as follows. To take a specific case, say 10:00 on October 19, we identify all stocks that have traded in the past fifteen minutes, ensuring that no price is more than fifteen minutes old. Using the closest transaction price in the past fifteen minutes to 10:00, we calculate the market value of these stocks and also the value of these same stocks using the closing prices on October 16. The ratio of the 10:00 market value to the closing market value on October 16 gives an estimate of one plus the return on the index from Friday close to 10:00.

Applying this return to the actual closing value of the index on October 16 of 282.70 provides an estimate of the index at 10:00. Alternatively, since the level of the index is arbitrary, one could set the index to one at the close of October 16 and interpret this ratio as an index itself.

The second approach is identical to the first in that it is based only upon stocks that have traded in the previous fifteen minutes. The difference is that, instead of the transaction price, this index utilizes the mean of the bid and ask prices at the time of the transaction.

The third approach utilizes only stocks that have traded in the next fifteen minutes and for these stocks using the nearest price in the next fifteen minutes to calculate the market value. The set of stocks using the past fifteen minutes will usually differ somewhat from the set of stocks using the next fifteen minutes.

One criticism of this approach is that, in the falling market of October 19, there may be some stocks that did not trade in either the past fifteen minutes or the next fifteen minutes because there was no one willing to buy. The argument goes that the returns on these stocks if they could have been observed would be less than the returns on those that traded. Excluding these stocks would then cause the index as calculated here to overstate the true index.

One way to assess this potential bias is to estimate a fourth index using the first available next trade price, whenever it occurs. This index corresponds to a strategy of placing market orders for each of the stocks in the index. In some cases, this price would be the opening price of the following day. However, if the next trade price is too far distant, the market could have fallen and recovered, so that the next trade price might even overstate the true unopened price at the time.

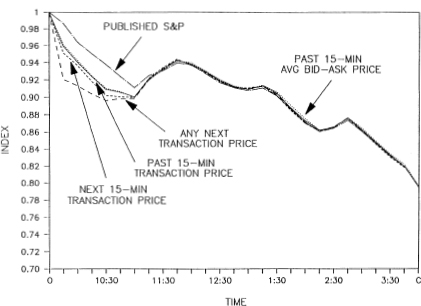

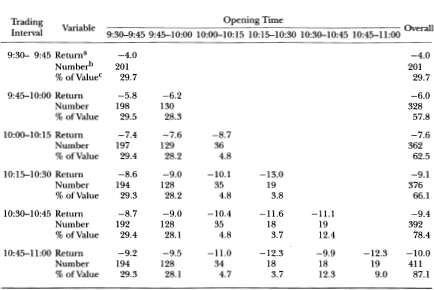

For October 19, the four indexes for the S&P stocks are very similar except for the first hour and a half of trading (Figure A12.1). This similarity stems from the fact that the bulk of the S&P stocks had opened and then continued to trade. By 11:00 on October 19, stocks representing 87.1 percent of the market value of the 462 NYSE stocks in the S&P Composite had opened and had traded in the prior fifteen minutes (Table A12.1). There was a tendency for the larger stocks to open later than the smaller stocks (Table A12.2). Thereafter, a substantial number of stocks traded in every fifteen-minute interval.

The differences in the indexes in the first hour and a half of trading are partly related to the delays in opening and to the rapid drop in the market. If the prices of stocks that have not opened move in alignment with the stocks that have opened, the true level of the market would be expected to fall within the index values calculated with the last fifteen-minute price and the next fifteen-minute price.

If, in the falling market of October 19, the true losses on stocks that had not opened exceeded the losses on stocks that had opened, the true market index might even be less than the index calculated with the next fifteen-minute price. This argument may have some merit. For any specific fifteen-minute interval from 9:45 to 11:00, there is a strong negative relation between the returns realized from Friday close and the time of opening (Table A12.1).

Figure Al2.1. Comparison of various constructed indexes measuring the S&P Composite Index with the published S&P Index on October 19, 1987. There are four types of constructed indexes, and they are calculated every fifteen minutes. The four constructed indexes differ in the estimate of the market value at each fifteen-minute interval. The first index (used in the body of the chapter) is based on all S&P stocks that traded in the previous or past fifteen minutes and utilizes the last transaction price in the interval to estimate the total market value of these stocks. The ratio of this market value to the market value of these same stocks as of the close on Friday, October 16, 1987, provides the index value that is plotted. The second index is the same as the first except that the estimate of the market values of the stocks at the end of the fifteen-minute interval utilizes as the price of each stock the mean of the last bid and ask price in the minute of the last transaction. The third is based upon S&P stocks that trade in the next fifteen-minute interval and estimates the market value by the earliest transaction price in the interval. The fourth is based upon S&P stocks that trade in any future interval on October 19 and estimates the market value by the earliest transaction price. The published index is the actual index rescaled to have a value of 1.0 as of the close on October 16. The indexes using future prices are only calculated through 3:45.

The behavior of these four indexes for S&P stocks for October 20 is similar to that of October 19 in that the four indexes approximate each other quite closely after the first hour and a half of trading. The major difference is that the market initially rose on October 20, and there is some evidence that the returns on stocks that opened later in the morning exceeded the returns of those that had already opened.

Table Al2.1. Realized returns from Friday close cross-classified by opening time and trading interval for S&P stocks during the first hour and a half of trading on October 19, 1987.

a Ratio of total market value of stocks using last prices in trading interval to total market value of same stocks using Friday closing prices, expressed as a percentage. The overall return is calculated in a similar fashion and is not a simple average of the returns in the cells.

b Number of stocks that opened at the designated time and traded in the trading interval.

c Ratio of total market value of stocks in cell to the total market value of all 462 stocks; both market values are based upon Friday closing prices.

Similarly, the four indexes for non-S&P stocks track each other closely after the first hour and a half of trading, but not quite as closely as the S&P indexes. Likewise, there is evidence that, in the falling market of October 19, the later opening non-S&P stocks experienced greater losses than those that opened earlier, and the reverse in the rising market of October 20.

In view of these results, the analyses of levels of the market will be based upon the indexes using only stocks that have traded in the past fifteen minutes. Further, since the S&P Composite Index utilizes transaction prices, we shall conform to the same convention. Utilizing the mean of the bid and ask prices leads to virtually identical results.

Table A12.2. Percentage of S&P stocks traded by firm size quartile in each fifteen-minute interval during the opening hour of October 19, 1987. The partitions for the quartiles are constructed to have approximately an equal number of stocks in each quartile. The numbers reported are the percentage of stocks that traded in the indicated interval out of the total number of stocks in the size category.

A12.2 Fifteen-Minute Index Returns

The analysis of aggregate order imbalances employs returns on the indexes over a fifteen-minute interval. One way to calculate such a return is to divide the index level at the end of one fifteen-minute interval by the index level at the end of the previous interval and express this ratio as a percentage return.

Another way is to use only stocks that have traded in consecutive fifteen minute intervals. The fifteen-minute return is then defined as the ratio of the market value of these stocks in one fifteen-minute interval divided by the market value of these same stocks in the previous interval and reexpressed as a percentage return.

In the first approach, the set of stocks in one fifteen-minute interval differs slightly from the set in the previous fifteen-minute interval, and this difference may introduce some noise into the return series. However, in comparison to the first approach, estimates based upon this second method employ a lesser number of securities which may introduce some noise. As a result, neither method clearly dominates the other.28

Since there is a theoretical possibility that the use of transaction prices might induce a positive correlation between the measure of order imbalance described in the body of the chapter and the estimated fifteen-minute returns, the results reported in the text will use the mean of the bid and the ask prices to measure market values. To conserve space, the principal empirical results reported in the text utilize the fifteen-minute returns based upon stocks that trade in consecutive fifteen-minute intervals. The results based upon other methods of estimating the fifteen-minute returns are similar.

1 Black Monday and the Future ofFinancial Markets (1989) contains excerpts of these various official reports. It also contains some interesting articles about the crash, separately authored by Robert J. Barro, Eugene F. Fama, Daniel R. Fischel, Allan H. Metzler, Richard W. Roll, and Lester G. Telser.

2 More technically, if the systematic factors in two large samples of stocks have on average similar factor sensitivities, one would expect the returns to be similar. Some of the statistical analyses will explicitly allow for differences in factor sensitivities.

3 As part of its report (1988), the SEC collected information on specific index-related selling programs. On October 19, these selling programs represented 21.1 percent of the S&P volume. The actual percentage is undoubtedly greater. Moreover, there are some trading strategies involving large baskets of stocks in the S&P that the SEC would not include as index related. Also of interest, the data collected by the SEC indicated that 81.0 percent of the index arbitrage on October 19 involved the December future contract on the S&P Composite Index.

4 Geewax Terker and Company collected these data on a real time basis from Bridge Data. Bridge Data also provides activity on other Exchanges, but the original collection process did not retain these data.

5 0n October 19, we found on occasion large differences between the price of the last trade on the NYSE and the last trade as reported in newspapers. For example, the price for the last trade for Texaco on October 19 on the NYSE was 30.875 and was reported at 4:03. In contrast, the closing price in The Wall Street Journal was 32.50. Some investigative work disclosed that a clerk on the Midwest Stock Exchange had recorded some early trades in Texaco after the markets had closed but had failed to indicate that the trades were out of sequence.

6 An analysis of the data from Bridge indicates that there were some trades reported during 2:05 p.m. and none during 2:07 p.m. on October 19. We have not been able to determine the reason for this slight discrepancy.

7 The number of shares outstanding that Standard & Poor’s uses in the construction of its indexes sometimes differs from the number reported in other financial publications. These shares outstanding are adjusted for stock dividends and stock splits during the month of October.

8 1n reconstructing the S&P index, it would be ideal to have the NYSE closing prices of NYSE stocks on Friday, October 16. Not having these prices, we utilize for this date the closing prices as reported on the Composite tape.

9 we also excluded foreign companies whose common stocks are traded through ADRs.

10 The adjustment is made separately for each size quartile.

11 These indexes are constructed in exactly the same way as the overall indexes and, thus, are value weighted. However, in view of the control for size, the range of the market values of the companies within each quartile is considerably less than the range for the overall indexes.

12 The differences in returns for the indexes reported in the text are reasonably accurate measures of what actually happened on October 19 and 20. The S&P index did decline more than the non-S&P index on October 19 and almost eliminated this greater decline by the morning of October 20. The purpose of this footnote is to assess whether the differences between the two indexes are statistically attributable to the inclusion or exclusion from the S&P index, holding constant other factors that might account for the differences. In this exercise, the other factors are the market values of the stocks as of the close on Friday, October 16, and the beta coefficients based upon weekly regressions for the fifty-two weeks ending in September 1987 on an equally weighted index of all NYSE stocks. (If there were less than fifty-two weeks of available data, betas were still estimated as long as there are at least thirty-seven weeks of data.)

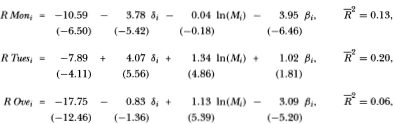

where R Moni is the return on stock i from the close on October 16 to the close on October 19; R Tuesi is the return, if it can be calculated, from the close on October 19 to the mid-morning price on October 20, defined as the traded price closest to 10:30 in the following fifteen minutes; R Ovei is the return from the close on October 16 to the mid-morning price on October 20; δi is a dummy variable assuming a value of one for S&P stocks and zero otherwise; Mi is the October 16 market value of stock i, and ßi is the fifty-two week beta coefficient. The sample for these regressions is the 955 stocks with complete data, of which 420 are S&P stocks. Heteroscedasticity-consistent z-statistics are in parentheses.

The estimates of the coefficients of these regressions are consistent with the relations presented in the text. The coefficient on the dummy variable is significantly negative on Monday, significantly positive on Tuesday, and nonsignificant over the two periods combined. On Monday, the beta coefficient enters significantly, while, on Tuesday, the market value enters significantly. Over the two periods combined, both the beta coefficient and the market value enter significantly. The behavior of the coefficients in these three regressions suggests that there is some interaction between market value and beta that the linear specification does not capture. The availability of two days of data for this study precludes our pursuing the nature of this interaction.

13 changes in offer prices and recording of transactions take place in part in diierent computers. If these computers at critical times are out of phase, there will be errors in sequences.

14 As examples, a smudged optical card or failure to code an order out of sequence would introduce errors.

15 Trades marked out of sequence are discarded.

16 Trades marked out of sequence are discarded.

17 An error might occur in the following scenario. Assume that the prior quote was 20 bid and 20 ask and the next prior quote was 19

ask and the next prior quote was 19 bid and 20 ask. The algorithm would classify a trade at 20 as a sell, even though it might be a buy.

bid and 20 ask. The algorithm would classify a trade at 20 as a sell, even though it might be a buy.

18 we use the mean of the bid and ask prices instead of transaction prices to guard against a potential bias. For example, during a period of substantial and positive order imbalance, there may be a greater chance that the last transaction would be executed at the ask price. If so, the return would be overstated and the estimated correlation between the return and the order imbalance biased upwards. Likewise, if the order imbalance were negative, the return would be understated, again leading to an upward bias in the estimated correlation. In fact, this potential bias is not substantial. In an earlier version of this chapter, we employed an alternative estimate of the fifteen-minute return, namely the ratio of the value of the constructed index at the end of the interval to the value at the end of the previous interval. This alternative utilizes transaction prices and does not require that a stock trade in two successive fifteen-minute periods. Although not reported here, the empirical results using this alternative measure are similar.

19 0n the basis of Fisher's z-test and twenty-five observations, any correlation greater than 0.49 is significant at the one percent level.

20 The selection of these particular intervals is based on an examination of the indexes in Figure 12.1. Other time periods considered lead to similar results.

21 The following analysis was repeated using transaction prices. The results did not change materially.

22 The usual t-values are, respectively, −8.84, 8.22, and −12.30.

23 We also regressed the Tuesday returns on the Monday returns separately for the 366 S&P stocks and for the 429 non-S&P stocks. The slope coefficient for the S&P regression is —0.68 with a z-statistic of —6.19, and the slope coefficient for the non-S&P regression is —0.42 with a —2 z-statistic of —4.73. The respective  ’s are 0.19 and 0.13.

’s are 0.19 and 0.13.

24 Kleidon(1 992) provides an analysis of this explanation.

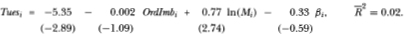

25 A more direct test of the price pressure hypothesis suggested by the referee is to regress Tuesday returns on some scaled measure of order imbalance for the last hour on Monday rather than on the return for this hour. To accommodate differences between S&P and non-S&P stocks, we report the regression separately for these two groups. The regression for the S&P stocks is

The regression for non-S&P stocks is

Ordlmbi is the appropriately scaled order imbalance, and the numbers in parentheses are z-statistics.

26 An alternative hypothesis consistent with the data is that S&P stocks adjust more rapidly to new information than non-S&P stocks, and, between the close on October 19 and the opening on October 20, there was a release of some favorable information. Under this hpothesis, the losses on non-S&P stocks on October 19 were not as great as they should have been.

27 The reader is referred to Hams (1989a) for another approach to mitigate biases associated with stale prices.

28 Another method to construct the levels of the index is to link the fifteen-minute returns derived from stocks that trade in consecutive intervals. This alternative is dominated by that given in the text of the Appendix. Relating market values at any point in time to the market values as of the close on Friday, October 16, assures that an error introduced into the index at one point in time would not propagate itself into future values of the index. Linking fifteen-minute returns would propagate such errors. Moreover, the method in the text utilizes as many stocks as available.