(PAPILIO POLYXENES)

You can find single eggs on the upper surface of a leaf and also on the stems and flowers of the host plant.

In its earliest stages, the caterpillar is dark and covered in tiny spikes. It has a patch of white on top, called a saddle.

As the caterpillar matures, it gradually loses its spikes and becomes striped and spotted.

WE LOVE TO WATCH the lazy back-and-forth movements of these velvety beauties as they sample wild milkweed in meadows and gardens. It’s easy to see them with wings open or closed: They always fan their wings as they feed.

Usually the caterpillars are green with black bands, but sometimes we see a black one like this. All have yellow spots on each body segment.

When the caterpillar is ready for the next phase, it hangs upright on a twig and spins a silk thread, or girdle, around its body.

The chrysalises may vary in color from bright green and yellow to dull brown and tan. In the fall they go into diapause until spring.

Just before the butterfly is ready to emerge, the chrysalis turns clear and you can see the wing markings.

The colors on the top surface of the open wings look very different from those on the closed wings. The blue is so bright, on this female, that it seems almost to glow.

Males are mostly black with yellowish spots.

When the butterfly is at rest, the bright orange spots on the underside of the wings are visible.

FIELD NOTES

Like other swallowtail caterpillars, the Black Swallowtail caterpillar (also known as the Parsley caterpillar) has a forked orange scent gland, called an osmeterium, that pops out to emit a nasty odor when the caterpillar feels threatened.

Like other swallowtail caterpillars, the Black Swallowtail caterpillar (also known as the Parsley caterpillar) has a forked orange scent gland, called an osmeterium, that pops out to emit a nasty odor when the caterpillar feels threatened.

The Black Swallowtail’s coloration is very much like the Pipevine Swallowtail’s. The fact that the Pipevine Swallowtail tastes bad may deter some of the Black Swallowtail’s predators.

The Black Swallowtail’s coloration is very much like the Pipevine Swallowtail’s. The fact that the Pipevine Swallowtail tastes bad may deter some of the Black Swallowtail’s predators.

The male Black Swallowtail has a row of large, light-colored spots across the middle of his wings.

The male Black Swallowtail has a row of large, light-colored spots across the middle of his wings.

The female has much smaller spots across her wings, and she wears a larger patch of beautiful blue scales on each lower wing.

The female has much smaller spots across her wings, and she wears a larger patch of beautiful blue scales on each lower wing.

Many kinds of plants are hosts to the Black Swallowtail, but we’ve had the most luck with fennel, dill, and Queen Anne’s lace (also called wild carrot).

Many kinds of plants are hosts to the Black Swallowtail, but we’ve had the most luck with fennel, dill, and Queen Anne’s lace (also called wild carrot).

(PAPILIO CRESPHONTES)

Giant Swallowtails lay their eggs on the top surface of plant leaves. The orange eggs darken before they hatch.

The young caterpillar is glossy and has bumps on its skin. Its colors make it look like a bird dropping, so birds are less likely to eat it.

The caterpillar undergoes some minor changes in color and overall appearance in its several molts.

FROM A HOMELY BROWNISH CATERPILLAR comes one of the largest of all North American butterflies. Some are as big as six inches across! Because the caterpillars feed on citrus leaves and the butterflies love citrus blossom nectar, the Giant Swallowtail is sometimes nicknamed “Orange Dog.”

The caterpillar grows to a length of about two inches during this stage.

When it feels threatened, the caterpillar extends a foul-smelling gland called an osmeterium, which looks like a snake’s tongue.

When the caterpillar is ready to change into a chrysalis, it hangs from a stem and spins a silk thread around its body.

The chrysalis is various shades of brown, sometimes with patches of green that look like lichen growth. The chrysalis remains in place through the winter.

The upper side of the Giant Swallowtail’s wings is very dark brown or black with a crisscross of yellow or cream-colored spots.

The underside of the wings is pale yellow, with iridescent light blue patches of scales on the lower wings.

FIELD NOTES

You’ll know the Giant Swallowtail by the two bands of yellow spots that extend across its open wings.

You’ll know the Giant Swallowtail by the two bands of yellow spots that extend across its open wings.

Because of their affection for tender leaves, large groups of Giant Swallowtail caterpillars may defoliate small young citrus trees.

Because of their affection for tender leaves, large groups of Giant Swallowtail caterpillars may defoliate small young citrus trees.

We’ve found our prickly ash most successful in attracting Giant Swallowtails, but the butterflies will also lay eggs, in smaller amounts, on our rue herbs. Both plants prefer full sun and well-drained soil. Prickly ash does have thorns, so be extra careful when handling this shrubby tree.

We’ve found our prickly ash most successful in attracting Giant Swallowtails, but the butterflies will also lay eggs, in smaller amounts, on our rue herbs. Both plants prefer full sun and well-drained soil. Prickly ash does have thorns, so be extra careful when handling this shrubby tree.

(BATTUS PHILENOR)

The female lays eggs in clusters around the stems and leaves of the host, Dutchman’s pipevine.

The first thing the newly hatched caterpillars do is eat their own eggshells before starting to chew on the plant leaves.

Most butterfly caterpillars are solitary feeders, but the Pipevines stay in groups and eat together at the edge of a leaf.

IF IMITATION IS THE SINCEREST form of flattery, lots of other butterflies want to flatter the Pipevine Swallowtail! Because of its iridescent blue scales, this elegant, medium-sized butterfly can easily be mistaken for the dark-color form of the Tiger Swallowtail or the female forms of the Eastern Black Swallowtail, Spicebush Swallowtail, and Red-spotted Purple. We always look twice.

As they mature, the caterpillars change from orange to velvety black with fleshy orange spikes.

The chrysalis looks similar to other swallowtail butterfly chrysalises but has a few more bumps at the base.

The chrysalis may be tan and brown or a mix of green and yellow. It will stay in diapause all winter.

The shiny metallic blue of the open wings on this male shows up best in bright sunlight. The metallic blue sheen is more subdued on the female.

When the Pipevine Swallowtail’s wings are closed, you can see its beautiful orange and blue coloring. The butterfly’s body is also covered in shiny blue scales.

FIELD NOTES

Birds and other predators find both the caterpillar and the butterfly forms of the Pipevine Swallowtail distasteful. Pipevine plants contain aristolochic acid, which is toxic to some animals.

Birds and other predators find both the caterpillar and the butterfly forms of the Pipevine Swallowtail distasteful. Pipevine plants contain aristolochic acid, which is toxic to some animals.

Pipevine Swallowtail males have more metallic blue color than do the females. The females have more prominent white spots on their wings.

Pipevine Swallowtail males have more metallic blue color than do the females. The females have more prominent white spots on their wings.

Fond of colorful flowers, Pipevines flutter constantly as they drink nectar, but don’t linger long at any one bloom. They are timid and nervous when approached and are strong, quick fliers that soar across our yards in a flash.

Fond of colorful flowers, Pipevines flutter constantly as they drink nectar, but don’t linger long at any one bloom. They are timid and nervous when approached and are strong, quick fliers that soar across our yards in a flash.

(PAPILIO TROILUS)

Single round eggs that look like tiny pearls are glued onto the underside of the host plant’s leaves.

The color and physical appearance of the caterpillar changes with each molt. The young caterpillar is brown and glossy.

As it grows and matures, the caterpillar turns greenish with blue dots. Too big now to pass for a bird dropping, the caterpillar’s green skin allows it to blend in among the plant leaves.

AS DRAMATIC AS A CITYSCAPE AT NIGHT, the velvety open wings of this woodland-loving butterfly are black, accented with brilliant white spots. In some places it’s called the Green-clouded Swallowtail because of the hazy blue-green of the male’s lower wings.

What large eyes it has! Actually, these are false eye-spots. The real head stays hidden under the front skin. At this stage you can see bright blue dots on the caterpillar’s translucent pink legs.

When the caterpillar is ready for the next phase, it turns pale yellow and hangs from a twig by spinning a silk thread around itself.

The chrysalis can be green or brown. In the fall, like all other swallowtails in northern states, it enters diapause until spring.

Wings open, the female butterfly displays her iridescent blue scales. On the male the scales are shiny pale green.

When the butterfly is at rest, you can see the bright orange spots that cluster on its lower wings.

FIELD NOTES

The caterpillar spins a mat of silk, which shrinks as it dries, curling the leaf’s edges. This gives the caterpillar a place to hide all day.

The caterpillar spins a mat of silk, which shrinks as it dries, curling the leaf’s edges. This gives the caterpillar a place to hide all day.

Look for folded spicebush leaves and you’ll locate sleeping caterpillars inside. They come out at night to eat.

Look for folded spicebush leaves and you’ll locate sleeping caterpillars inside. They come out at night to eat.

Wrens in our yards bite through the center of a folded spicebush leaf to eat the caterpillar inside. Some spiders also use their silk to fold over a leaf and hide this way, but the wrens are insect eaters, so they win a meal either way.

Wrens in our yards bite through the center of a folded spicebush leaf to eat the caterpillar inside. Some spiders also use their silk to fold over a leaf and hide this way, but the wrens are insect eaters, so they win a meal either way.

Spicebush butterflies are drawn to the nectar of our butterfly bushes and lantanas.

Spicebush butterflies are drawn to the nectar of our butterfly bushes and lantanas.

(PAPILIO GLAUCUS)

Look for single round green eggs laid on the top of a leaf. The eggs blend in very well with surrounding foliage.

At first the caterpillar is brownish with a white midsection. Some people mistake caterpillars at this stage for bird droppings.

As it sheds its skin, the caterpillar becomes a beautiful light green with two small yellow-orange and black eyespots. The front of the caterpillar looks swollen compared to the back.

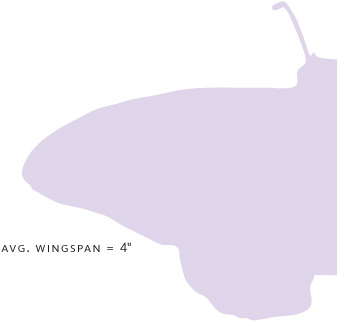

HAVE YOU EVER SEEN A GROUP OF LARGE BUTTERFLIES gathered at a mud puddle? They could be Tiger Swallowtail males, sipping the salts and minerals they need for reproduction. You’ll recognize them by the tigerlike yellow and black stripes across their wings and the long, thin black “tail” that extends from each lower wing.

This caterpillar is spinning a mat of silk threads to cover the top of the leaf. When the silk dries, it shrinks and folds the leaf, creating a place to hide from predators.

The caterpillar turns dark brown when it is ready to pupate. A silk thread holds it upright on a stick as it prepares to shed its skin one last time.

The chrysalis may be green or shades of brown. In the autumn it enters diapause until spring, when the butterfly emerges. These two chrysalises look like branches on the twigs.

The male Tiger Swallowtail is yellow with bold black stripes, like a real tiger.

Female Tiger Swallowtails may exhibit this second color form, called dimorphic coloration. This dark-colored female form is more common in Georgia and Florida than elsewhere in the butterfly’s range.

Only with the wings closed can you see the bright orange spots that decorate the underside of the bottom wings.

FIELD NOTES

A disturbed Tiger Swallowtail caterpillar will sometimes rear up and head-butt anything that gets close.

A disturbed Tiger Swallowtail caterpillar will sometimes rear up and head-butt anything that gets close.

This butterfly’s long tongue enables it to reach into tubular flowers and sip nectar that other butterflies can’t reach.

This butterfly’s long tongue enables it to reach into tubular flowers and sip nectar that other butterflies can’t reach.

Most Tiger Swallowtails lay eggs in treetops, one egg to a leaf. Locating the eggs and caterpillars can be difficult unless you keep your trees pruned. To find a caterpillar, look for a curled-up leaf being used as a hiding place. Partially eaten leaves may also give away the caterpillar’s location.

Most Tiger Swallowtails lay eggs in treetops, one egg to a leaf. Locating the eggs and caterpillars can be difficult unless you keep your trees pruned. To find a caterpillar, look for a curled-up leaf being used as a hiding place. Partially eaten leaves may also give away the caterpillar’s location.

Several types of trees, including sweet bay magnolia and tulip poplar, are common hosts. The sweet bay is a relatively small tree with a rather sparse leaf count. The tulip tree, on the other hand, can grow to be several stories tall and requires more space in your yard.

Several types of trees, including sweet bay magnolia and tulip poplar, are common hosts. The sweet bay is a relatively small tree with a rather sparse leaf count. The tulip tree, on the other hand, can grow to be several stories tall and requires more space in your yard.

(EURYTIDES MARCELLUS)

These two eggs were laid by the same female. The empty-looking one is a “dud”; the green one will hatch.

At first the caterpillar is bluish gray with tiny stripes. At this stage it looks like a little slug.

We’ve seen caterpillars ranging in color from shades of green to occasionally black, like this one.

WITH ITS LONG KITE TAILS AND GRACEFUL GLIDING FLIGHT, the Zebra Swallowtail is a delightful show-off. We’re glad the pawpaw tree is common where we live, because it’s the only tree Zebras lay their eggs on.

When it’s ready to pupate, the caterpillar hangs upright from a stem and spins a silk harness around itself.

Compared with other swallowtail chrysalises, these seem small and compact, especially considering that such large butterflies emerge from them.

This butterfly is ready to break out of its chrysalis; the wing pattern shows through the chrysalis shell.

White areas of the Zebra’s wings may sometimes appear pale greenish. Look for scarlet dots near the inside bottom of each lower wing.

Although the black stripes seem somewhat muted, the Zebra’s thin scarlet stripe stands out sharply.

FIELD NOTES

The longest tails of any butterfly in North America belong to the Zebra. Its tails and triangular wings make it part of the Kite family of butterflies.

The longest tails of any butterfly in North America belong to the Zebra. Its tails and triangular wings make it part of the Kite family of butterflies.

Zebras emerging in spring have shorter tails and may be paler than those that emerge in summer.

Zebras emerging in spring have shorter tails and may be paler than those that emerge in summer.

The only host plant for the Zebra is the pawpaw tree. It often grows in wooded areas near streams, and sprouts easily from large seeds.

The only host plant for the Zebra is the pawpaw tree. It often grows in wooded areas near streams, and sprouts easily from large seeds.

Female Zebras are easy to approach and photograph when they’re focused on laying their eggs.

Female Zebras are easy to approach and photograph when they’re focused on laying their eggs.

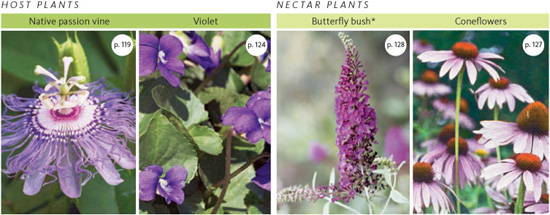

(AGRAULIS VANILLAE)

The Gulf Fritillary female lays her eggs on passion vines, especially on the curly, spiraling tendrils.

This caterpillar has just molted. Until the new skin dries and hardens a bit, it’s especially vulnerable to attack.

The caterpillar eventually turns dark orange and its spikes blacken. It eats the leaves and tendrils of the passion vine.

THE WARM AREAS AROUND THE GULF OF MEXICO are this butterfly’s favorite neighborhoods, and like some exotic tropical creature, it lives on passionflowers. We love to watch it with its wings wide open, absorbing heat from the early-morning sun to dry off last night’s dew.

As the caterpillar grows, it becomes darker and glossier. The spikes look scary, but they’re harmless.

The chrysalis may be tan and cream-colored. It looks like a dead leaf.

Some chrysalises are dark brown. The deep indentation in the middle is typical for a Gulf Fritillary.

The delicate black lines and small spots of the Gulf Fritillary’s open wings look almost as if they’ve been drawn in ink on soft absorbent paper. Shown here is a female; the male’s black edging is less pronounced.

When its wings are closed, you can see the dramatic silver spots, like teardrops, that make this butterfly so striking. Its body is fuzzy, with brown and white stripes.

FIELD NOTES

Although they normally frequent the Gulf of Mexico, Gulf Fritillary females occasionally wander far enough north to lay their eggs on our passion vines.

Although they normally frequent the Gulf of Mexico, Gulf Fritillary females occasionally wander far enough north to lay their eggs on our passion vines.

Its diet makes the Gulf Fritillary caterpillar poisonous to predators. The caterpillars favor passion vine flower buds.

Its diet makes the Gulf Fritillary caterpillar poisonous to predators. The caterpillars favor passion vine flower buds.

Unable to survive freezing temperatures, this butterfly stays in the warmer southern states all winter long.

Unable to survive freezing temperatures, this butterfly stays in the warmer southern states all winter long.

Flashy silver spots on the wings’ undersides make Gulf Fritillaries easy to identify.

Flashy silver spots on the wings’ undersides make Gulf Fritillaries easy to identify.

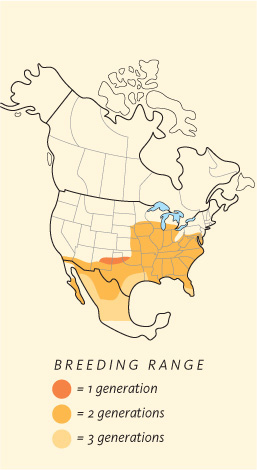

(EUPTOIETA CLAUDIA)

We’ve found cream-colored Variegated Fritillary eggs on several parts of our passion vines, including the leaves, stems, and tendrils.

The caterpillar changes very little in color and appearance when it sheds its skin. Its cousin the Gulf Fritillary lacks these white markings.

The mature caterpillar is glossy orange with white markings. It’s covered in black spines with lots of branching points.

WE’RE ALWAYS DELIGHTED WHEN VARIEGATED FRITILLARIES appear in our gardens. They’re common in southern states such as Georgia and Florida, but only occasionally wander north into our area. They fly with quick darting motions and stay close to the ground.

The caterpillar hangs upside down, ready to shed its skin for the last time. The skin has split open to reveal the chrysalis underneath.

Once it dries, the chrysalis has a beautiful mother-of-pearl sheen and is covered with golden spikes.

The color patterns of each chrysalis tend to be unique. Some are mostly white and others have lots of brown patches.

Like many other fritillaries, the Variegated’s open wings reveal black spots and wavy blackish lines on a tawny background.

With its wings closed, the butterfly looks like a dried leaf. This coloration helps hide it from predators.

FIELD NOTES

They may look a bit scary, but these caterpillars won’t sting or cause a rash if you handle them.

They may look a bit scary, but these caterpillars won’t sting or cause a rash if you handle them.

Unable to survive freezing temperatures at any stage of its life cycle, the butterfly form of the Variegated Fritillary immigrates south to warmer regions during the winter.

Unable to survive freezing temperatures at any stage of its life cycle, the butterfly form of the Variegated Fritillary immigrates south to warmer regions during the winter.

Like other fritillaries, Variegated caterpillars can eat violets. Like Longwings, they can also eat passion vines.

Like other fritillaries, Variegated caterpillars can eat violets. Like Longwings, they can also eat passion vines.

(HELICONIUS CHARITONIUS)

Zebra Longwings lay their yellow eggs on passion vines. We think the eggs look like miniature ears of corn.

The caterpillar is ghostly white and covered in prickly, branched black spines. Its appearance stays basically the same as it goes through several molts.

Although the spines look like little needles, they’re actually flexible and won’t hurt your skin.

THE NAME DESCRIBES IT WELL: Long striped wings, each punctuated with a curving row of pale yellow dots, give this striking butterfly elegance and grace. Look for groups of these butterflies at the forest’s edge in the evening, as they like company when they sleep.

When the caterpillar hangs upside down to shed its skin for the last time, it turns pale brown.

The chrysalis is light brown and covered in tiny barbs that may give it some protection against hungry predators.

From this view, the chrysalis looks like a tiny bat hanging upside down.

The Zebra Longwing’s vivid stripes are easy to see against its solid black background.

Although its colors are more muted when it’s perching this way, the Zebra’s stripes are still clear and distinctive.

FIELD NOTES

A diet of passion vines makes the Zebra Longwing caterpillar toxic to birds.

A diet of passion vines makes the Zebra Longwing caterpillar toxic to birds.

Although they normally live south of us, Zebra Longwings occasionally visit our habitat gardens and lay eggs.

Although they normally live south of us, Zebra Longwings occasionally visit our habitat gardens and lay eggs.

The Zebra’s tongue secretes digestive enzymes that help it digest protein-rich pollen specks as it “drinks.” This supplement to its nectar diet allows the Zebra to live longer than other butterflies, perhaps by several months.

The Zebra’s tongue secretes digestive enzymes that help it digest protein-rich pollen specks as it “drinks.” This supplement to its nectar diet allows the Zebra to live longer than other butterflies, perhaps by several months.

The Zebra’s flight is slow and meandering, in spite of those long wings. But just try to catch one!

The Zebra’s flight is slow and meandering, in spite of those long wings. But just try to catch one!

(POLYGONIA INTERROGATIONIS)

The Question Mark female may lay her eggs in stacks. See the empty “duds” on the top and bottom of the left-hand stack?

The caterpillar looks like the punctuation mark it’s named for as it lies curled up on a leaf.

When mature, the caterpillar may have white dots and yellow or orange lines along its black body, as well as yellow or orange spines.

RAGGEDY, IRREGULARLY SPLOTCHED WINGS give the Question Mark a shabby look, and its love of fermented fruit and animal feces is difficult for humans to appreciate. But we like to watch these wary little butterflies, and they’re often up and flying around on very chilly mornings, hours before any other butterflies appear.

If it feels threatened, the caterpillar tends to curl up or drop to the ground to avoid predators. You can handle it safely, although it will feel prickly to the touch.

We’ve found that the coloration of Question Mark caterpillars varies widely. Some are black with orange spines; others, like the one shown here, have yellowish spines and areas of orange and black.

The chrysalis is subtle shades of tan or brown and has shiny metallic spots on the outward-facing side.

When it is at rest, you can see the glowing ultraviolet edges of the Question Mark’s wings. This butterfly is displaying the light-colored winter form. The summer form has very dark, almost black lower wings, with little or no pattern visible.

Would you mistake this butterfly for a ragged old leaf? Its neutral-colored, mottled wings help it remain inconspicuous when perched on tree bark to drink leaking sap. Can you see the shiny silver question mark shape in the center of the wing?

FIELD NOTES

Hungry Question Mark caterpillars munch on our hop vines and on our elm and hackberry trees.

Hungry Question Mark caterpillars munch on our hop vines and on our elm and hackberry trees.

Most butterfly caterpillars spin white silk, but the Question Mark caterpillar creates a pad of pink silk to anchor its chrysalis to a leaf or stem.

Most butterfly caterpillars spin white silk, but the Question Mark caterpillar creates a pad of pink silk to anchor its chrysalis to a leaf or stem.

Question Marks emerge from their chrysalises in the fall and spend the winter as inactive adults, hiding in woodpiles or under loose tree bark until spring.

Question Marks emerge from their chrysalises in the fall and spend the winter as inactive adults, hiding in woodpiles or under loose tree bark until spring.

The adult butterflies prefer to sip juices from rotting fruit, tree sap, and animal droppings. Animal droppings contain proteins that nectar lacks.

The adult butterflies prefer to sip juices from rotting fruit, tree sap, and animal droppings. Animal droppings contain proteins that nectar lacks.

Summer-flying adults have dark, almost black hind wings. Adults flying in the fall have mostly orange-colored hind wings.

Summer-flying adults have dark, almost black hind wings. Adults flying in the fall have mostly orange-colored hind wings.

Look for the Question Mark perching, as it often does, head down on the side of a tree trunk.

Look for the Question Mark perching, as it often does, head down on the side of a tree trunk.

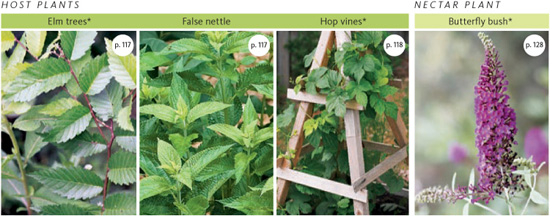

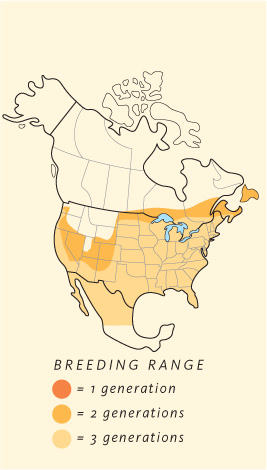

(POLYGONIA COMMA)

The Comma female lays her eggs on hop vines, elm trees, false nettle, and hackberry trees. Sometimes she stacks them together.

The growing caterpillar is covered with harmless white spines.

With every molt, the caterpillar’s colors and spines look a bit different. Overall, though, it’s still mostly white.

HERE’S A BUTTERFLY THAT ISN’T INTERESTED IN OUR FLOWERS! The Comma — also known in some places as the “hop merchant” because of the caterpillar’s love of hop leaves — is drawn instead to mud, sap, and fruit. Its fast, erratic flight makes it difficult to catch.

When the caterpillar feels threatened, it curls up and plays dead. It may even drop off the plant.

The chrysalis is shades of pale brown. It has several shiny silver spots that look as if they were painted on.

When you look at a Question Mark chrysalis (at left) and a Comma chrysalis side by side, you see how similar they are. The surest way to tell them apart is to notice the caterpillar before it pupates or to watch the butterfly emerge.

We seldom see the orange and brown pattern on the Comma’s open wings. We find the Comma very difficult to photograph with its wings open because of its constant, rapid flapping.

The closed wings are marked like tree bark. Look for the tiny silver comma shape in the middle of each bottom wing.

FIELD NOTES

Comma caterpillars may be small, but they can eat a lot of hop leaves. They start by chewing the edges of the leaves and work their way gradually toward the center. They don’t eat the hop’s tough veins or stems, so the leaf skeleton is all that’s left clinging to the vine when they’ve finished.

Comma caterpillars may be small, but they can eat a lot of hop leaves. They start by chewing the edges of the leaves and work their way gradually toward the center. They don’t eat the hop’s tough veins or stems, so the leaf skeleton is all that’s left clinging to the vine when they’ve finished.

Smaller than the Question Mark butterfly, the Comma comes out of hibernation a little earlier in the spring.

Smaller than the Question Mark butterfly, the Comma comes out of hibernation a little earlier in the spring.

The Comma likes to lay its eggs in hackberry trees. Consider carefully where you plant a hackberry tree because it can grow to be 70 feet tall.

The Comma likes to lay its eggs in hackberry trees. Consider carefully where you plant a hackberry tree because it can grow to be 70 feet tall.

A good place to look for Commas in spring is a woodpile. The inactive adults sometimes spend the winter hiding there, emerging when the weather begins to warm up.

A good place to look for Commas in spring is a woodpile. The inactive adults sometimes spend the winter hiding there, emerging when the weather begins to warm up.

In the 19th century, the metallic spots on a “hop merchant’s” chrysalis were said to predict the year’s hop prices: Gold spots forecast high prices and silver ones meant prices would be low.

In the 19th century, the metallic spots on a “hop merchant’s” chrysalis were said to predict the year’s hop prices: Gold spots forecast high prices and silver ones meant prices would be low.

(JUNONIA COENIA)

Buckeyes glue their eggs to the underside of plantain, toadflax, and snapdragon leaves.

The caterpillars eat large quantities of leaves and seem to grow faster when they eat plantain.

Most Buckeye caterpillars are dark colored, with bright blue dots at the base of each spine on their backs and broken yellow lines down the length of their bodies.

EVER HAVE THE FEELING YOU’RE BEING WATCHED? If there’s a Buckeye around, multiply that by three! Those big eyespots fool some predators into thinking that the Buckeye is a force to be reckoned with. We like to watch these butterflies basking on a sunny patch of open earth or sipping from our stonecrop flowers.

The Buckeye caterpillar has many fleshy feet that act almost like suction cups, helping the insect cling (even upside down) to twigs and plant stems.

This Buckeye caterpillar is hanging from a twig in preparation for shedding its skin and entering the chrysalis phase.

Each chrysalis has a unique color pattern. Notice the seam running down the left side. The chrysalis will split open there to release the butterfly.

(LEFT) Occasionally, when one of our Buckeyes emerges from its chrysalis, it displays this washed-out color (pale form). (RIGHT) Look at the beautiful iridescent eyespots on this dark form. The eyespots are defensive markings, making the Buckeye seem to be a larger creature.

When closed, the Buckeye’s wings have a pale cream and brown pattern that helps camouflage it.

FIELD NOTES

Easily spooked, Buckeye caterpillars will fall off their host plant to hide at the least sign of trouble.

Easily spooked, Buckeye caterpillars will fall off their host plant to hide at the least sign of trouble.

Toadflax and plantains, both nonnative weeds, are host to Buckeye caterpillars.

Toadflax and plantains, both nonnative weeds, are host to Buckeye caterpillars.

Buckeye butterflies often sit on bare ground with their wings outstretched to soak up some sun. Males sometimes perch for hours at a time, waiting for a potential mate.

Buckeye butterflies often sit on bare ground with their wings outstretched to soak up some sun. Males sometimes perch for hours at a time, waiting for a potential mate.

When disturbed, Buckeyes fly rapidly, close to the ground, but often return to land in the same spot.

When disturbed, Buckeyes fly rapidly, close to the ground, but often return to land in the same spot.

The distinctive eyespots of the Buckeye make it relatively easy to identify.

The distinctive eyespots of the Buckeye make it relatively easy to identify.

If they don’t fly south, Buckeyes may die during our harsh winters in northern Kentucky. Once the cool days of October set in, we don’t see them again until spring.

If they don’t fly south, Buckeyes may die during our harsh winters in northern Kentucky. Once the cool days of October set in, we don’t see them again until spring.

(VANESSA VIRGINIENSIS)

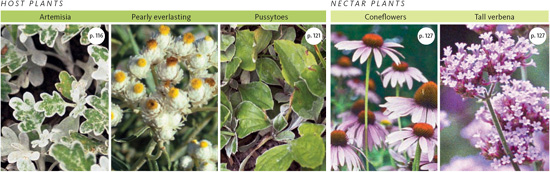

An American Lady female lays her eggs one at a time on pearly everlastings, artemisia, and pussytoes.

The caterpillar is covered in many branched spines as well as dots and stripes along its entire body.

When it feels threatened, the caterpillar curls up and may drop straight to the ground in order to escape from danger.

QUICK AND WARY, THE AMERICAN LADY CAN BE very difficult to observe closely. With frantic darting movements, it eludes the curious gardener and even the stealthy photographer. The wings are quicker than the eye, and this Lady seems to fly sideways and even backward to escape observation.

As many other caterpillars do, the American Lady hangs upside down in a J position to pupate.

Most of the chrysalises that we’ve seen are tan or brown and resemble a dead, dried-up leaf.

The less common chrysalis color variation is yellowish green with brown markings.

The chrysalis becomes thin and transparent, revealing the wing colors, before the butterfly is ready to emerge.

Black at the wing tips, orange around the body, the American Lady can be hard to distinguish from its cousin the Painted Lady (page 72) when its wings are open.

See the two large eyespots on the lower wing? In contrast, the Painted Lady (page 72) has four or five eyespots.

FIELD NOTES

American Lady caterpillars make a silky nest inside the leaves of their host plant, living in and feeding on them. If you see several leaves of pearly everlastings stuck together, most likely there is a caterpillar inside.

American Lady caterpillars make a silky nest inside the leaves of their host plant, living in and feeding on them. If you see several leaves of pearly everlastings stuck together, most likely there is a caterpillar inside.

Once the weather turns cold, American Ladies disappear from our gardens and we don’t see them again until spring.

Once the weather turns cold, American Ladies disappear from our gardens and we don’t see them again until spring.

American Ladies prefer open areas and low-growing host and nectar plants.

American Ladies prefer open areas and low-growing host and nectar plants.

When its wings are open, this butterfly shows one white spot floating inside a square orange patch on each of the top wings. The Painted Lady does not have this mark.

When its wings are open, this butterfly shows one white spot floating inside a square orange patch on each of the top wings. The Painted Lady does not have this mark.

(VANESSA CARDUI)

The Painted Lady female lays her eggs one at a time on the top surfaces of leaves. The eggs are a lovely blue or green and have ridges all around.

The caterpillars don’t seem to mind eating together as a group. As they munch, they spin loose webs of silk around the leaves, which help hide them from predators.

The fully grown caterpillar is mostly black and has lots of pale hairs and branched spines.

THE LOVELY PAINTED LADY IS A REGULAR VISITOR to our flower gardens. This dappled beauty makes frequent stops to sip nectar or to tease us by perching on a shoulder or hat brim. The playful antics of this social butterfly add a bit of fun to a hot day of gardening.

When it is time to pupate, the caterpillar hangs upside down from a twig or plant stem and sheds its skin one last time.

The tan chrysalis is covered in shiny gold dots that make it look more like a piece of jewelry than an insect.

The orange wing markings are visible through this chrysalis. The butterfly will be ready for eclosion (emergence) soon.

Dappled orange and black, with white spots scattered over the upper wings, the Painted Lady’s open wings look like a sunny patch on a leafy woodland floor.

See the four eyespots on the lower wing? They prove that this is a Painted Lady; the American Lady (page 70) has only two.

FIELD NOTES

Professional breeders and schools often choose to raise Painted Lady caterpillars because they can be fed an artificial diet. This saves them the trouble of growing particular host plants and makes the Painted Lady easy to rear.

Professional breeders and schools often choose to raise Painted Lady caterpillars because they can be fed an artificial diet. This saves them the trouble of growing particular host plants and makes the Painted Lady easy to rear.

Because its favorite host plants are wild thistles, the Painted Lady used to be called the Thistle Butterfly. Their world-wide presence has allowed the Painted Lady to take up residence throughout North America, Asia, Africa, and Europe. We don’t suggest planting thistles in your garden, however, because they can irritate your skin and tend to be invasive.

Because its favorite host plants are wild thistles, the Painted Lady used to be called the Thistle Butterfly. Their world-wide presence has allowed the Painted Lady to take up residence throughout North America, Asia, Africa, and Europe. We don’t suggest planting thistles in your garden, however, because they can irritate your skin and tend to be invasive.

In autumn Painted Ladies fly south because they can’t survive the harsh winter weather up north. We see them in our yards in their greatest numbers in September.

In autumn Painted Ladies fly south because they can’t survive the harsh winter weather up north. We see them in our yards in their greatest numbers in September.

(VANESSA ATALANTA)

Red Admirals lay their green, barrel-like eggs on the topmost tender leaves of their host plants. These eggs have been laid on a false nettle.

Tiny at first, the blackish caterpillar has a black head covered in hairs.

As the caterpillar grows, it develops many branched spines that may help protect it from predators.

LOVERS OF ROTTING FRUIT AND TREE SAP, Red Admirals are sociable and easy to spot: They look as if someone painted a bright red-orange semicircle on each of their open wings. They fly with a quick, darting habit and are fond of the coneflowers in our gardens.

More-mature caterpillars may have orange spots around their spines. You may also find caterpillars that show patterns of white or yellow.

Unlike those species that wander far away, the Red Admiral caterpillar may stay on its host plant until it becomes a butterfly. When it is fully grown and ready to enter the chrysalis phase, the caterpillar hangs upside down to shed its skin.

The chrysalis can be various shades of brown or gray, decorated with shiny metallic gold spots.

The bright orange-red semicircle and the white spots at the wing tips show up clearly against the brown-black background.

Mottled brownish wings provide good camouflage in the woods. Instead of eyespots, this butterfly has blue heart shapes on its inner wings.

FIELD NOTES

The caterpillar may spin silk threads onto a host plant’s leaf, folding it over to create a tent to hide in.

The caterpillar may spin silk threads onto a host plant’s leaf, folding it over to create a tent to hide in.

Adult butterflies drink flower nectar but prefer to sip rotting fruit juices and tree sap. If the rotting fruit has fermented, the butterflies can get drunk!

Adult butterflies drink flower nectar but prefer to sip rotting fruit juices and tree sap. If the rotting fruit has fermented, the butterflies can get drunk!

Because they crave salt in human sweat, don’t be surprised to find a Red Admiral sitting on your shoulder in the garden.

Because they crave salt in human sweat, don’t be surprised to find a Red Admiral sitting on your shoulder in the garden.

Red Admirals fly south, sometimes in large numbers, when the weather starts to cool down in the fall. In the spring they wander back to the northern states looking for food.

Red Admirals fly south, sometimes in large numbers, when the weather starts to cool down in the fall. In the spring they wander back to the northern states looking for food.

(CHLOSYNE NYCTEIS)

The Silvery Checkerspot female lays her cream-colored eggs in clusters under the leaves of our purple coneflowers.

After hatching, the caterpillars remain together, eating as a group until they pupate. They scrape the leaf surface, leaving behind a “skeleton” of stems and veins.

Don’t let their small size fool you. These caterpillars will devour a lot of coneflower leaves in just a few days. They don’t eat the flowers, though, so we still have blooms to enjoy.

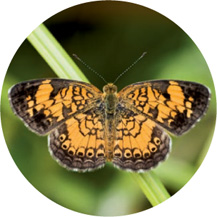

LOOK FOR THE SILVERY CHECKERSPOT IN MOIST WOODLANDS: It has a fondness for small streams and creek beds. On the move, it darts quickly and erratically, close to the ground. When it perches, it keeps its wings wide open. The males of the species like to gather around animal droppings or in areas where there’s plenty of damp soil.

The caterpillars spin a patch of silk to hang from, and then assume this J position to prepare for the chrysalis phase.

The chrysalis is shades of cream and brown with several rows of short spikes. The earthy colors make it difficult to spot among our garden plants.

These siblings formed their chrysalises together. When disturbed, they’ll twitch and jump around.

You can tell from the way the wing colors show through the chrysalis that this butterfly is ready to break free and cling to a plant to let its wings dry.

The tiny white circles toward the bottom of the Checkerspot’s lower wings are different from the similarly placed solid black dots of its close relative, the Pearl Crescent (page 111).

The pale silvery spots checkered on the underside of its wing give this butterfly its name.

FIELD NOTES

Caterpillars of this species that hatch in late summer will not grow to their full size in one season, but instead will spend the winter hibernating at the base of the host plant. They won’t wake up to feed and mature until spring.

Caterpillars of this species that hatch in late summer will not grow to their full size in one season, but instead will spend the winter hibernating at the base of the host plant. They won’t wake up to feed and mature until spring.

Be careful during fall garden cleanup: Young Silvery Checker-spot caterpillars may be hibernating at the base of your cone-flowers for the winter. Don’t disturb them!

Be careful during fall garden cleanup: Young Silvery Checker-spot caterpillars may be hibernating at the base of your cone-flowers for the winter. Don’t disturb them!

This small butterfly’s flight is fast and erratic. It is a bit larger than the Pearl Crescent (page 111).

This small butterfly’s flight is fast and erratic. It is a bit larger than the Pearl Crescent (page 111).

The female is larger than the male and glides low to the ground when a male pursues her.

The female is larger than the male and glides low to the ground when a male pursues her.

(LIMENITIS ARTHEMIS ASTYANAX)

The Red-spotted Purple female lays a single egg at the very tip of the leaf. Each egg is covered in dimples like a golf ball.

When the caterpillars are young, they eat the tip of the leaf and often leave the tough vein intact.

When the caterpillar is disturbed, it curls up, lies very still, and looks like a bird dropping.

The caterpillar, which develops lumpy skin and prickly antennae, may be shades of tan, cream, or brown.

ALTHOUGH IT DOESN’T HAVE LONG TAILS, the Red-spotted Purple closely resembles the bad-tasting Pipevine Swallowtail (page 29), and most birds avoid it. We appreciate its beautiful, relaxed flying habit and its amazing iridescence. Because the Red-spotted Purple prefers woodlands, we consider its appearance among our garden flowers a rare treat.

This Red-spotted Purple caterpillar is resting on a willow leaf.

Caterpillars born in late summer stop growing after about a week. They use silk to roll up a leaf to hibernate in until spring arrives.

The Red-spotted Purple’s chrysalis is the same drab colors as the caterpillar. It blends in well among stems and branches in the garden.

When the butterfly’s wings are open, the beautiful iridescent blue coloration is vivid, especially in bright sunlight.

The bright orange spots on the closed wings are striking.

FIELD NOTES

Red-spotted Purple caterpillars and their chrysalises are very similar to Viceroy caterpillars and their chrysalises.

Red-spotted Purple caterpillars and their chrysalises are very similar to Viceroy caterpillars and their chrysalises.

We see these butterflies only one at a time, usually when a female is laying her eggs on our various willows.

We see these butterflies only one at a time, usually when a female is laying her eggs on our various willows.

These butterflies like to sip juices from rotting fruit. They’re one of the most frequent visitors to our rotting-fruit trays. They also feed on carrion, sap, and animal droppings.

These butterflies like to sip juices from rotting fruit. They’re one of the most frequent visitors to our rotting-fruit trays. They also feed on carrion, sap, and animal droppings.

(LIMENITIS ARCHIPPUS)

The Viceroy female lays a single egg at the very tip of a leaf of the host plant. This may make it harder for predators to find.

The baby caterpillar is brown with a white saddle. Find one by looking for chewed leaf tips in trees.

If born in early summer, the caterpillar continues to grow. It often looks just like a Red-spotted Purple caterpillar (page 84), but may be olive-colored instead of brown.

VICEROY, MONARCH, OR QUEEN? If you have only a few seconds to decide, look at the lower wing: A thick black line loops across only the Viceroy’s. The Viceroy flaps its wings a little less often than do the others, pausing to glide from time to time. It’ll pause to sip too, with its wings half open, on our sweet william, coneflowers, or lantana.

In colder regions a caterpillar born in the fall makes a leaf tube, called a hibernaculum, as a hiding place to spend the winter months.

In the hot summer months, when the caterpillar is ready to pupate, it hangs upside down from a branch and undergoes its final molt to reveal the chrysalis.

The chrysalis of the Viceroy looks the same as that of the very closely related Red-spotted Purple (page 85).

The Viceroy is a smaller butterfly than the Monarch (page 94) and has a distinctive black line that runs horizontally across its lower wings.

Because of its similar bright colors, the Viceroy is often mistaken for the better-known Monarch (page 94). When its wings are closed, it also resembles the Queen butterfly (page 98).

FIELD NOTES

Viceroy caterpillars look like bird droppings, as do Red-spotted Purple caterpillars (page 84). This may slow down their predators somewhat.

Viceroy caterpillars look like bird droppings, as do Red-spotted Purple caterpillars (page 84). This may slow down their predators somewhat.

Birds avoid the Viceroy butterfly because it looks so much like the bad-tasting Monarch. Recent research suggests, however, that the Viceroy also tastes bad.

Birds avoid the Viceroy butterfly because it looks so much like the bad-tasting Monarch. Recent research suggests, however, that the Viceroy also tastes bad.

Willows are hardy and available in many varieties and leaf shapes. We have corkscrew willow and dwarf blue leaf arctic willow in our gardens, and Viceroys lay eggs on both.

Willows are hardy and available in many varieties and leaf shapes. We have corkscrew willow and dwarf blue leaf arctic willow in our gardens, and Viceroys lay eggs on both.

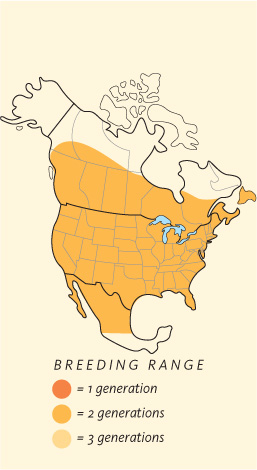

(DANAUS PLEXIPPUS)

We usually find a single egg under a host milkweed leaf. We’ve sometimes found them on milkweed flowers and seedpods.

The bright stripes warn predators that this caterpillar is not a tasty meal.

After it hatches, the caterpillar eats the milkweed’s leaves. The plant’s toxic glycosides are absorbed into the caterpillar’s body, and do not hurt it.

PROBABLY THE MOST RECOGNIZED, most studied butterfly in North America, the Monarch is loved and watched by children and adults alike. Who can help but be attracted to the bright striped caterpillar and glittering green chrysalis that eventually become this orange and black beauty?

When the caterpillar is ready for the next phase, it hangs upside down from a patch of silk that it has spun.

The pale green chrysalis is adorned with shiny golden dots. The chrysalis matches the color of plant leaves.

Just before the butterfly emerges, the chrysalis becomes transparent and the wings can be seen.

The Monarch’s wing veins, deep black against a burnt orange background, are visible whether the wings are open or closed. Large and small white dots are sprinkled around the edges of the wings and all over the Monarch’s black body.

Males have scent glands on their lower wings that produce pheromones for mating; they appear as small black spots on the wing veins.

The Monarch’s orange color is more subtle when the wings are closed. Don’t mistake this butterfly for its similarly colored cousin, the Viceroy (page 90): The Monarch is larger.

FIELD NOTES

Four black filaments adorn the caterpillar’s body.

Four black filaments adorn the caterpillar’s body.

Monarch caterpillars absorb toxins from milkweed plants into their bodies. The toxins will sicken birds, lizards, and mammals, but predators like wasps and spiders are immune to them.

Monarch caterpillars absorb toxins from milkweed plants into their bodies. The toxins will sicken birds, lizards, and mammals, but predators like wasps and spiders are immune to them.

The green chrysalis of the Monarch looks almost identical to that of the Queen butterfly (page 97).

The green chrysalis of the Monarch looks almost identical to that of the Queen butterfly (page 97).

The only butterfly that migrates north and south every year is the Monarch, although no single Monarch makes the trip in both directions.

The only butterfly that migrates north and south every year is the Monarch, although no single Monarch makes the trip in both directions.

Host plants for the Monarch are those belonging to the Milkweed family. The wild milkweeds do not transplant well and should be collected only as seedpods in the fall.

Host plants for the Monarch are those belonging to the Milkweed family. The wild milkweeds do not transplant well and should be collected only as seedpods in the fall.

An organization called Monarch Watch tags Monarchs before they migrate so they can be tracked when they reach Mexico.

An organization called Monarch Watch tags Monarchs before they migrate so they can be tracked when they reach Mexico.

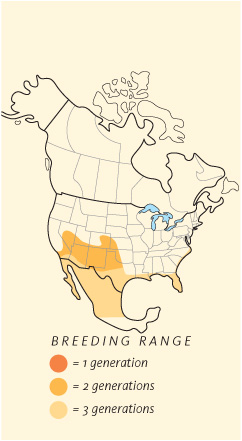

(DANAUS GILIPPUS)

You can find oval cream-colored Queen eggs on the underside of milkweed leaves. The eggs gradually become transparent; here you can see the caterpillar’s dark head getting ready to chew its way out of the egg.

This is a newly hatched Queen caterpillar. It eats its own eggshell as soon as it hatches and then looks for a tender leaf.

Like its cousin the Monarch (page 92), the Queen depends on milkweed as its host plant, and it stores the plant toxins in its body for self-defense.

THIS COUSIN OF THE MONARCH ROYAL FAMILY is somewhat less showy, especially when you see its simply patterned wings wide open, from above. When it is flying energetically from one milkweed flower to the next, you might have to look carefully to tell the Monarch from the Queen.

The color and the appearance of the Queen don’t change much with each molt. Notice the caterpillar’s six black filaments sticking up from its body. Monarchs have just four.

Is this caterpillar coming or going? Maybe predators can’t tell either, since there seem to be antennae on both ends.

Here you can see that the green chrysalis of the Queen looks almost identical to that of the Monarch (page 93).

Here’s a male with open wings. Unlike the Monarch, whose veins show through on both sides of its wings (page 94), the Queen’s wing veins are not visible from above.

This Queen butterfly is a male. The dark circle on the lower wing is a scent gland used to produce pheromones.

The female Queen does not have a dark scent gland. This is the easiest way to tell a male from a female, whether it’s a Queen or a Monarch.

FIELD NOTES

Queen caterpillars make no attempt to hide. They store milkweed plant toxins in their bodies, and predators have learned to avoid them.

Queen caterpillars make no attempt to hide. They store milkweed plant toxins in their bodies, and predators have learned to avoid them.

Voracious eaters, the caterpillars steadily devour every part of the milkweed host plant except the roots and tough stems.

Voracious eaters, the caterpillars steadily devour every part of the milkweed host plant except the roots and tough stems.

A year-round resident of Florida, the Queen seldom wanders very far northward, but is often released into butterfly conservatories for public viewing.

A year-round resident of Florida, the Queen seldom wanders very far northward, but is often released into butterfly conservatories for public viewing.

The easiest way to distinguish the Queen from its Monarch cousin when in flight is by its darker color. The Queen is almost brown instead of orange.

The easiest way to distinguish the Queen from its Monarch cousin when in flight is by its darker color. The Queen is almost brown instead of orange.

(PIERIS RAPAE)

Cabbage White butterflies lay their eggs on — you guessed it! — cabbage plants. They will also lay their eggs on nasturtiums and spider flowers.

Because the Cabbage White lays so many eggs at one time, its large broods of caterpillars quickly devour any host plant.

The small green caterpillars love nasturtiums and plants in the Mustard family. They also eat spider flower (Cleome) leaves.

CABBAGE WHITES, WHICH SPEND A GREAT DEAL OF TIME chasing each other through our yards, look like bits of paper fluttering around. We often have more than 20 of them at a time, dancing a graceful aerial ballet.

Cabbage White caterpillars often attach themselves to a leaf to pupate. Can you see the tiny silk pad at the rear and the thin thread of silk at this caterpillar’s middle?

The chrysalises are green or tan. We often find one hanging right on its host plant. They spend the cold winter months in chrysalis form, waiting for warmer spring days as a signal to emerge.

The silk-thread harness has broken and the butterfly is moments from breaking free.

Smudges on the insides of the wing tips, like a dusting of charcoal, help identify the Cabbage White.

The male Cabbage White has only one black dot on each forewing. Females, like the one above, have two.

FIELD NOTES

Farmers are not thrilled with the Cabbage White caterpillar; they consider it an agricultural pest.

Farmers are not thrilled with the Cabbage White caterpillar; they consider it an agricultural pest.

Although not native to North America, the Cabbage White has made itself at home here and flourished. You can find this butterfly almost anywhere.

Although not native to North America, the Cabbage White has made itself at home here and flourished. You can find this butterfly almost anywhere.

Although cabbage is a main host for the Cabbage White, we prefer to plant pretty spider flowers in our garden. The cabbage tends to stink after a while.

Although cabbage is a main host for the Cabbage White, we prefer to plant pretty spider flowers in our garden. The cabbage tends to stink after a while.

One of the reasons we enjoy this butterfly is that it’s easy to approach. It’s not as jumpy and nervous as are some other types of butterflies.

One of the reasons we enjoy this butterfly is that it’s easy to approach. It’s not as jumpy and nervous as are some other types of butterflies.

Cabbage Whites continue to mate and lay eggs until the first frost.

Cabbage Whites continue to mate and lay eggs until the first frost.

(COLIAS PHILODICE)

Sulphur butterflies lay their tiny eggs on clover leaves. At first the eggs are white, then become cream or pale yellow, and finally turn red before the caterpillars hatch.

The bright green caterpillar is almost invisible to the casual observer, because it likes to lie along the middle vein of the leaf.

This small species grows to be only about an inch long. You could have a lawn full of them and not even know it.

ALMOST CONSTANTLY IN MOTION, the Sulphur creates a familiar patch of fluttering yellow anywhere there are open fields or parks. We like to plant areas of clover especially for Sulphurs, and watch their quick flight just above the level of the flowers.

The pale green chrysalis is suspended from a twig by a thin silk thread; it is also attached by a patch of silk at the rear end. At this stage you could easily mistake the chrysalis for a leaf.

Before the butterfly emerges, its chrysalis takes on a pink tint and the wing pattern inside becomes visible. See the dark pink “zipper” at the top? This section splits open to allow the butterfly to crawl out.

The open wings are bright yellow with black trim and each sports a black dot. Females, like the one shown here, have yellow dots in the top black wing margin; males do not.

When the wings are closed, you can see the characteristic shiny silver spot on the underside of the hind wing. If you look carefully, you will notice the pink fringe around each of the wings. Sulphurs have green eyes.

FIELD NOTES

Clouded Sulphur caterpillars are as green as grass and almost impossible to find on their host plant. Unless you actually witness a female Sulphur butterfly laying her eggs, you will probably never see the tiny eggs or the resulting caterpillars.

Clouded Sulphur caterpillars are as green as grass and almost impossible to find on their host plant. Unless you actually witness a female Sulphur butterfly laying her eggs, you will probably never see the tiny eggs or the resulting caterpillars.

More of a challenge to photograph than other species, we find the Sulphur skittish, and its flight pattern seems to go all over the place!

More of a challenge to photograph than other species, we find the Sulphur skittish, and its flight pattern seems to go all over the place!

Puddles are attractive to Sulphurs; they like the salts they find there.

Puddles are attractive to Sulphurs; they like the salts they find there.

Females may be yellow or white. You can tell a Cabbage White butterfly from a Sulphur by the pink edges around the Sulphur’s wings and the characteristic silver spot on the hind-wing’s underside.

Females may be yellow or white. You can tell a Cabbage White butterfly from a Sulphur by the pink edges around the Sulphur’s wings and the characteristic silver spot on the hind-wing’s underside.

Sulphurs seem to like yellow flowers; we often see them sipping nectar from dandelions. The yellow background acts as a kind of camouflage.

Sulphurs seem to like yellow flowers; we often see them sipping nectar from dandelions. The yellow background acts as a kind of camouflage.

(PHYCIODES THAROS)

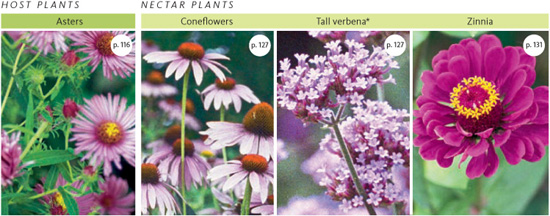

Look for clusters of very small eggs on aster leaves.

The young caterpillar eats the leaves of aster plants. As cold weather approaches, it stops eating and spends the winter resting at the base of the plant until spring arrives.

The caterpillar has brown spines, sometimes with a white tip and an orange base.

SOMETIMES KNOWN AS THE PEARLY CRESCENTSPOT, this butterfly can be seen in open meadows or wherever asters grow in profusion. They’re not very big, but they’re very common, flapping and coasting not far from the ground, just above the level of the flowers they love.

Sometimes the caterpillar stays on the original host plant to make its chrysalis. The dull brown of the chrysalis makes it look very much like a small dead leaf hanging from a stem.

Here are three Pearl Crescent chrysalises next to a clover leaf (at right). Notice how little they are!

The female of the species has more black coloration on her wings.

The male has more orange areas on his wings.

The underside of the wings reveals intricate details.

FIELD NOTES

Pearl Crescent caterpillars eat very little foliage from their host aster plants. Your flowers will continue to look nice, even when the caterpillars are living on them.

Pearl Crescent caterpillars eat very little foliage from their host aster plants. Your flowers will continue to look nice, even when the caterpillars are living on them.

These butterflies seem just to show up overnight in late summer as our asters are beginning to bloom. They are one of the most common butterflies we see as we walk through woods that adjoin wild meadows.

These butterflies seem just to show up overnight in late summer as our asters are beginning to bloom. They are one of the most common butterflies we see as we walk through woods that adjoin wild meadows.

Fast, erratic flight characterizes the Pearl Crescent: The butterfly darts from flower to flower, low to the ground.

Fast, erratic flight characterizes the Pearl Crescent: The butterfly darts from flower to flower, low to the ground.

Pearl Crescent butterflies are so small they can stand on a blade of grass.

Pearl Crescent butterflies are so small they can stand on a blade of grass.