The anti-Communist crusade and the blacklist that it imposed ended Hollywood’s brief flirtation with the real world and ensured that the fledgling television industry would never begin one.

Ellen Schrecker (historian)1

In her talk [Anne Revere] she said that … in Hollywood there is a group of organized writers, artists, musicians, actors and actresses and which group is working toward a better world, a modern world for tomorrow, but that the result of their efforts has branded them as disloyal. She said that she and all of the ten people from Hollywood who went to Washington are American citizens but are endangered.

Rodney Stewart (FBI Agent, Los Angeles)2

“The year of the melting pot” was the catchphrase that American magazine TV Guide used to describe the 1960 fall prime-time television line-up. Although media critics like Jean Muir and Fredi Washington thought that roles for more mature actresses were still in short supply, there was no denying that prime-time television had never been so widely representative of the experiences of the many people who lived in the U.S. In response to thousands of fan letters from television viewers, Molly Goldberg was on the air and back in school, finishing a law degree so that she could defend the rights of refugees and the foreign-born. New head of the CBS documentary unit, Shirley Graham, had produced a line-up of investigative segments with a focus on civil rights cold cases. The first episode focused on the unsolved murder of teenager Emmet Till by white supremacists. Lena Horne was starring in her own variety show, with network NBC promising that she would bring her elegant brand of style and feminist humor to the small screen. Fredi Washington headlined in a drama written by Vera Caspary based on the life of investigative journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida Wells Barnett. And the producers of the popular Western Bonanza announced plans for a spin-off in which Berkeley-educated actor Victor Sen Yung (who played cook Hop Sing on the series) fought anti-Chinese exclusion laws to reunite with his physician wife and children.

Of course, TV Guide never used such a catchphrase. And no such programs appeared on American television, the people who might have written, produced, or performed in them having been fired or silenced by the blacklist. Instead, in the years between 1949 and 1952, anti-communists used the blacklist to determine which stories would be told on television and other media and, subsequently, in schools, workplaces, and homes for years to come. This unprecedented ability, only partly realized with radio, gave them the power to determine whose experiences of America would be visible, validated, and valorized, and whose would be belittled or redacted.

Instead of these imaginary programs, the blacklist transformed Lena Horne’s democratic desire for “the Negro to be portrayed as a normal person … as a worker at a union meeting, as a voter at the polls, as a civil service worker or an elected official” into a dangerous form of subversion.3 Because she refused to downplay her Jewishness, Judy Holliday was typecast in ways that were “patently false and vaguely insulting.” Biographer Gary Carey reflected that there was something unsettlingly “distasteful about watching Judy play women who were always so much cruder and less intelligent than herself.”4 Even those who successfully resisted stereotyping found, like Lena Horne, that “they didn’t make me into a maid. But they didn’t make me into anything else either. I became a butterfly pinned to a column singing away in Movieland.”5 By rendering progressive perspectives on America disgraceful and un-American, anti-communists built racism and misogyny into the storytelling machinery of the industry. It also built these into the industry’s workplace practices and cultures, the treatment of women and people of color on screen, as we have seen, directly reflecting how the men who ran the industry thought about women and people of color and justified continued discrimination.

Literary scholar Courtney Thorsson says of a later era of black feminist literary critics that they were inspired by the knowledge that they were “unearthing, creating, and practicing an African American archive” that had been hitherto concealed from view.6 The account of progressive women’s oppositional work in and around the new medium of television is a first step in excavating a similar archive. Viewed from the perspective of this archive of oppositional work, located across unexpected places and sources, my fictional account of 1960s television shows is not as farfetched as it might initially appear. Many of the Broadcast 41 devoted their professional lives to narrating and performing stories about American experiences that defied the G-Man’s formula, leaving evidence of these efforts before, during, and after the blacklist. However much their work may have been redacted from television history and cultural memory, the Broadcast 41 were far more than casualties of the blacklist. By actively opposing the views of anti-communists, they were powerful precursors of ideas and perspectives that would not appear on television with any regularity until the turn of the twenty-first century.

This chapter is only the beginning of a larger, ongoing effort to recover the work that the forty-one women listed in Red Channels, and others like them, were prevented from contributing to the new medium of television. This is no speculative history. It exists in various places for those seeking to uncover it. The novels and other published work of the Broadcast 41 are concrete evidence of the themes and ideas they were exploring. The criticism that they published in newspapers and magazines highlights their opposition to the mainstream of media production. Some left the U.S. and worked in other, less restrictive national media industries, leaving additional traces of oppositional work. Performers continued to work in theater, where they challenged writers to create more complex portrayals of those who were marginalized within mainstream cultures and gave performances that moved audiences to listen and respect these. The thousands of fan letters written to people like the Broadcast 41 prove that audiences valued programming appealing to intellect and understanding rather than white defensiveness and rage. The archived papers of the Broadcast 41 provide other clues about work that was prevented from appearing. And generations of scholars—most of them women, many of them women of color—have written theses and dissertations on these women that explore in detail many of the themes and ideas this book could only hint at.7

What the Broadcast 41 had made, what they were making when the blacklist occurred, and what they only dreamed of making as reflected in materials like the above add up to a counterfactual history of television, based on a massive alternative archive, a dreamscape of the powerful anti-racist, proto-feminist voices and content that existed before the G-Man’s fantasies became television’s reality. This history points to the evolution of ideas that might have taken place in television long years ago, if it had continued to respond to the work of progressive women and people of color and their powerful criticisms of media industries’ treatment of them, on-screen and off. This archive of resistance and opposition offers new ways of thinking about audiences as well, minus the power of anti-communists to render women, people of color, and immigrants either unworthy of the industry’s respect or beneath its vision.

❖ ❖ ❖

I decided many years ago to invent myself. I had obviously been invented by someone else—by a whole society—and I didn’t like their invention.

Maya Angelou (poet, memoirist, civil rights activist)8

She did not go along with the crowd. Not because she was a Negro. She was not; she was White. Not because she was an Indian, but because a Southern White woman said that slavery was a cancer eating into our national life, and that it will in the end destroy us if we do not wipe it out; because she talked about the churches who sent missionaries to Africa and yet held slaves in their own backyard … that woman’s name has been wiped out of history!

Shirley Graham (musician, writer, civil rights activist)9

Throughout a life and career tragically cut short by the blacklist, actor Canada Lee powerfully called for a new set of storytelling practices, one that might center the experiences of African Americans. Where, he asked,

is the story of our lives in terms of the ghetto slums in which we must live? Where is the story of our lives in terms of the fact that in walking from our houses to the corner store we may be attacked and beaten? Where is the story of our lives in terms of the jobs not available, the very years of life guaranteed to a white man which are denied to us? Where is the story of how a Negro baby born at the same time in the same city as a white baby can be expected to die 10 years sooner? Where is the story of the lives of our people? Who would know us if he had to know us by listening to Amos ’n’ Andy, to Beulah, to Rochester, to the minstrel show?10

Although largely excluded from making mass-produced popular culture like film and television, African American writers and performers like Canada Lee, Shirley Graham, Lena Horne, Paul Robeson, Hazel Scott, and Fredi Washington created popular culture that made visible the long history of struggles against white supremacy.

As historian Milly Barranger has documented, in the years before the blacklist, New York City theater generated attention to race and class that would be prevented from energizing and transforming television in the 1950s and 1960s. Fredi Washington’s career took off with a role in one of the first Broadway shows to be written and directed by African Americans, Shuffle Along (1921); she co-starred with Ethel Waters in Mamba’s Daughters; she shared the billing with Bill Robinson in One Mile from Heaven; and she starred in Emperor Jones with Paul Robeson.

Although many of these plays remain boxed into what Horne criticized as “cliché presentations of Negro life … folksy things,” they offered an improvement over the minstrelsy of vaudeville and the stereotypes of Hollywood.11 In 1943, Margaret Webster went a step further, directing a production of Othello with Paul Robeson in the title role, José Ferrer as Iago, and Uta Hagen as Desdemona (all of whom would be listed along with Webster in Red Channels less than a decade later). In the mid-1940s, Fredi Washington starred in a remarkable (if very short-lived) black-cast production of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, some sixty years before filmmaker Spike Lee’s retelling of that story in his 2015 film, Chi-Raq.12 In 1947, Washington, Robeson, Webster, and other progressives helped form the Committee on the Negro in the Arts, whose stated objectives, as literary scholar Kathlene McDonald notes, were to eradicate racial stereotyping and generate employment for African Americans in the arts.13

In the decades before the postwar rise of television, Shirley Graham explored experiences that had been suppressed from American history. Working first in music and theater, as a musician, playwright, critic, and later novelist, Graham told stories to mainstream audiences from a perspective distinctly her own. Her first major work—the opera Tom-Tom: An Epic of Music and the Negro (1932)—grew out of her childhood experiences watching pageants like W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1913 The Star of Ethiopia celebrating the history of black people in America.14 The first opera written by a black woman, Tom-Tom honored and expanded on the work of a previous generation of African American cultural producers, narrating the historical arc of a community, from its kidnapping by slavers through a revolution set against the backdrop of 1920s Harlem.

Less than a decade later, Graham was the first woman to direct one of the Federal Theatre Program Negro Units, where she took the controversial step of adapting white supremacist popular culture for anti-racist purposes. In 1938, Graham produced a reimagining of Helen Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo. Bannerman’s story about a Tamil child had been popular across regional and local theater in the U.S., the white supremacy of the South Indian Sambo finding a racist counterpart in the minstrelsy of American popular culture.15 Recognizing that the popularity of Little Black Sambo would draw people to theaters, Graham attempted to reinterpret the narrative so that it focused on the inventiveness and creativity of African culture rather than the stereotypes characteristic of minstrelsy.

Where other Federal Theatre Project productions of Little Black Sambo in places like Cincinnati, Ohio; Miami, Florida; and Newark, New Jersey featured white actors in blackface or puppets with the exaggerated racist features characteristic of minstrelsy, Graham’s Pan-African version cast black actors, costumed them in African attire, and created dialogue written in lyric prose rather than dialect.16 She portrayed the child as a trickster figure—intelligent, resourceful, and resilient. Although it is difficult to know what audiences made of the performance, the popularity of the production exposed theater-goers to radically different images and ideas about race. Anti-communists were threatened enough by anti-racist efforts like this that they shut down the Federal Theatre Project in 1939.

In the 1940s, Graham turned to writing novels for young people about racism and resistance, the achievements of women, and histories about the struggles of immigrants and poor people. Like her Federal Theatre Project productions, her novels about abolitionist Frederick Douglass; almanac writer, surveyor, mathematician, and farmer Benjamin Banneker; city of Chicago founder Jean-Baptiste Pointe de Sable; and poet Phillis Wheatley participated in a much larger conversation among those who wished to present “the case of the Negro in the making of American history,” as Graham described it.17 Her novels worked against traditions that, as feminist critic Barbara Smith put it decades later, considered the historical and cultural contributions of black people as “beneath consideration, invisible, unknown” to “white and/or male consciousness.”18 Graham herself participated in this suppressed tradition of writers and critics who wrote about African American historical figures because, like her, they “felt that Negroes were misunderstood, and were not known, and were outside of history.” In 1948, CBS broadcast a teleplay of Shirley Graham’s novel The Story of Phillis Wheatley, evidence of the growing popularity of her work.

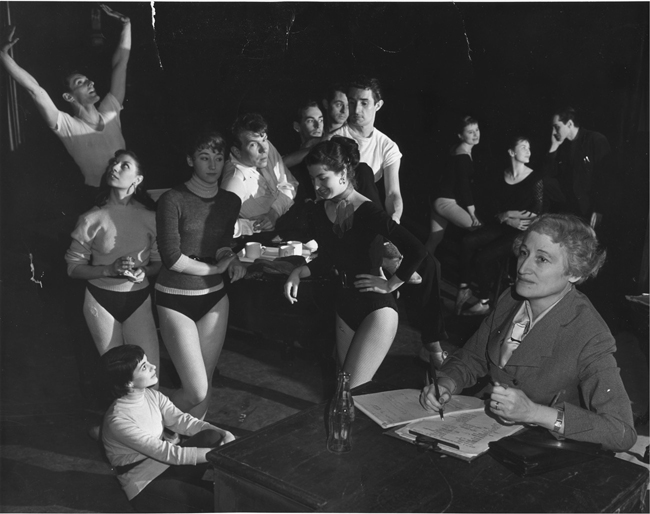

Inspired by the work of black progressives, other progressive women joined the project of chronicling African Americans’ contributions to American history and their struggles against white supremacy. Blacklisted dancer and choreographer Helen Tamiris, considered one of the founders of modern dance, believed that “no artist can achieve full maturity unless he recognizes his role as a citizen, taking responsibility, not only to think, but to act.” She put her beliefs into practice in her work with the Federal Theatre Project in New York City.19 In 1937, she created “How Long, Brethren?” a dance that performed African American protest songs in order to use those traditions to issue “a call for direct action” in the present.20 While the work of white women like Tamiris was by no means free of the limitations of their own racialized points of view, they were significant challenges to white supremacist popular culture.

Rather than appropriating black culture, Dorothy Parker turned critical eyes on the ugliness and hypocrisy of white supremacy in her short story “Arrangement in Black and White.” In it, Parker offered a spare and trenchant critique of gendered white supremacy, recounting the dinner party interactions of a white “woman with the pink velvet poppies twined round the assorted gold of her hair,” a woman who visually embodies all the time-honored traits of white femininity. She asks her host to introduce her to the party’s guest of honor, a black singer named Walter Williams. This icon of white femininity voices the racism of her absent husband, who, she confides to her host, is “really awfully fond of colored people.… as long as they keep their place.” The story concludes as the woman observes that she and her husband will share a laugh about the fact that she addressed Williams as “mister” in their brief exchange of words, demonstrating that this awful fondness was merely a cover for the foulest kind of racism.21

In the 1930s and 1940s, progressive-era women also made popular culture that combatted anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic prejudices (Figure 6.1). Gertrude Berg, who earned a place on the gray list because of her defense of blacklisted co-star Philip Loeb, wrote about the worsening situation of European Jews in the 1930s, at a time when both film and broadcasting were loath to do so.22 The Goldbergs showcased Berg’s desire to show Jews “as they really are,” trying to chart a course between “the broken dialect and smutty wise-cracks of the Jewish comedians” and “the gushing, sugar-coated sentimentalities of many of the ‘good-willers.’”23

For more than twenty years, The Goldbergs presented a very different understanding of what it meant to be American from the anti-communists who later put an end to The Goldbergs’ long broadcast run. Berg said that the sitcom was based on “all the immigrant families I knew in New York City.”24 In contrast to stereotypical representations of Jewish people in popular culture, Berg showed immigrant family life in richer complexity. Judging from the volume of fan mail the program received, The Goldbergs resonated with other immigrant groups, capturing the generational tensions between first-generation Americans and their assimilationist children, who often had to teach parents “how to become Americans.”25

Berg’s version of Americanism celebrated a New Deal ethos of solidarity and mutual support. In this and other regards, her distinctly working-class and ethnic sense of community could not have been more dissimilar from that of anti-communists like Ayn Rand, who exhorted people instead to “Remember that all the great thinkers, artists, scientists were single, individual, independent men who stood alone, and discovered new directions of achievement—alone.”26 In contrast to the dog-eat-dog individualism of anti-communists like Rand, when Molly’s husband Jake complained about helping to subsidize their relatives’ emigration to America, Molly chided him: “No matter vhat anybody is got, dey got trough de help of somebody else. By ourselves ve couldn’t make notting. You know dat, Jake.”27

The Broadcast 41 also told stories about experiences of gender that did not conform to the G-Man’s formula for domesticity. Vera Caspary wrote novels, short stories, and screenplays about women who worked for their living and relished their reproductive and economic independence (Figure 6.2). Caspary’s mysteries were celebrated for her use of multiple points of view to explore what one reviewer described as “realistic and moving portraits of young female wage earners.”28 Unlike Helen Gurley Brown’s later portraits of young women workers pursuing well-off husbands so they could leave the workforce, or women who went to college to get what was described in 1950s America as an “MRS degree” (meaning they were in college to land an upwardly mobile spouse), Caspary’s girls pursued work as a means to independence. As we have seen, Caspary struggled mightily against the objections of executives and directors in her efforts to represent these female wage earners with dignity and respect.29

Caspary’s novels and screen plays also criticized the genre of romance and its reliance on an economic system that caused women to invest in miserable and sometimes lethal relationships with men. In Laura (1943), Caspary held romance accountable for women’s ruin. Laura had been trapped by “the dream [that] still held her, the hero she could love forever immaturely.”30 Caspary’s narrator in Thelma (1952) listens unhappily to the common sense of her era, as her childhood friend advises her, “You intelligent girls can have your careers, she told me one day and her voice made of intelligence a disability, ‘but for me it’s enough to be a wife.’”31 Throughout her career, Caspary resisted the sexist conventions of romance. “You’ll be happy to know,” she wrote in 1962 to her editor at Dell Publishing, that her manuscript “won’t be called Happily Ever After.”32

Progressive women’s work in radio in the 1930s and 1940s offers additional clues to the narratives about gender that they might have contributed to television. Naturally, their own shifting experiences as women were sources of inspiration. Berg’s first series, Effie and Laura (1927), drew on themes related to the changing roles of white women in U.S. society, based on the lives of two female salesclerks from the Bronx, who discussed “everything from men to politics.”33 Reflecting ongoing conflicts between conservative industrial forces and the perspectives of women producers, Effie and Laura was cancelled by CBS after the first episode aired because network executives apparently disapproved when Laura observed, “marriages are never made in heaven.”34

In the decades before the blacklist, women even made inroads into the male-dominated realm of radio news programming. Mary Margaret McBride moved from print journalism to radio in 1934, creating a long-running talk show that, as broadcast historian Donna Halper puts it, “was as much about interesting people in the news as it was about the domestic arts.”35 Where McBride worked in the more feminized domain of human interest, Lisa Sergio’s WQXR program, Lisa Sergio’s Column of the Air (1936–46), encroached on broadcast journalism, a profession almost wholly dominated by men. In it, Sergio used her own experiences of fascism to analyze its migration to South America, to criticize the support that neutral countries were providing fascists through trade, and to convey an international perspective on the war and its aftermath.36

Other women participated in this interwar groundswell of creativity in broadcasting through their work in soap operas, a genre G-Men considered frivolous and largely unworthy of their attention. Irna Phillips, who would later become known as the queen of the soaps, helped create some of the first radio programs that addressed female audiences, programs that were also preoccupied with the changing roles of white women, such as Painted Dreams (1930–43) and Joyce Jordan, Girl Intern (1938–52), the latter of which became Joyce Jordan, MD and featured the first female doctor on radio.37 Writer Elaine Sterne Carrington created content that reflected new career and educational options for young women in the first half of the twentieth century, including popular serials like Pepper Young’s Family and Rosemary (starring Broadcast 41 actress Betty Winkler).

On occasion, the successes of progressive theater productions persuaded Hollywood to take a chance on adapting content for film. In 1946, Ruth Gordon’s husband, Garson Kanin, made his first foray into play writing with the surprise hit Born Yesterday. According to scholar Judith Smith, “Kanin wrote the part of Billie Dawn, the streetwise and brazen ‘dumb blonde’ mistress of a crooked junk dealer, for Jean Arthur, based, he commented retrospectively, ‘on a stripper he once knew who read Karl Marx between shows.’”38 Judy Holliday took over the role at the last minute and helped make the show a hit: it ran on Broadway for three years. The film version was released in 1950 to box office success and critical acclaim, despite attacks by anti-communists.

In addition to Born Yesterday, Garson Kanin co-wrote with Ruth Gordon a series of successful romantic comedies starring Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. These films reflected what happened when progressives wrote about gender, their scripts featuring white women on more equal footing with men, as lawyers in Adam’s Rib (1949) and as athletes in Pat and Mike (1952).39 Both films are in many ways witty and self-reflexive meditations on Gordon and Kanin’s own exasperating professional relationship. In a scene in Adam’s Rib, lawyer for the defense Amanda Bonner (played by Katherine Hepburn) encourages her witness (a female bodybuilder) to hoist prosecuting attorney and husband Adam Bonner above her head in a wry commentary on the physical supremacy of men. Pat and Mike’s Pat Pemberton (played by Hepburn), an athlete unable to compete in the presence of her domineering fiancé, finds reassurance and love in the shape of a man who supports her aspirations rather than feeling threatened by them.

These examples allude to original narratives about race, gender, class, and nation that would be glimpsed only sporadically on television in the years that followed the blacklist. The blacklist caused viewers to be treated to a far more lackluster diet of G-Man-approved fare in 1960 than the one imagined at the beginning of this chapter. Molly Goldberg would indeed go to college in 1961, but as “Mrs. G.” and not an advocate for civil rights. Westerns like The Rifleman, Maverick, The Lawman, Tales of Wells Fargo, The Texan (its hero a Confederate captain), and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp emphasized the virtues of male autonomy and individualism. Although in 1965 The Big Valley featured Barbara Stanwyck as the tough and resilient matriarch of the Barkley Ranch, for the most part Westerns excluded women altogether. Bonanza, The Rifleman, and The Lawman showcased men whose wives or love interests had died or whose narratives did not feature women as recurring characters. Women were relegated to comedies like The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Donna Reed Show, The Betty Hutton Show, and Father Knows Best or soaps, while white men appeared as guardians of law and order in a world apparently populated mainly by them.

❖ ❖ ❖

Adrian and Joan LaCour Scott (writers, scene cut from script of Have Gun, Will Travel)40

The Broadcast 41’s perspectives were not as easily eliminated as female characters in television Westerns or pesky scenes that hinted at women’s dissatisfaction with a world where everything that was interesting or exciting was reserved for men. Progressives who could afford to left the U.S. for work in Europe or Mexico, some were driven to the margins of television or other media industries in their quest for work, or to other professions altogether. The spectral traces of their presence in places outside prime-time television give us additional ideas about what television might have looked like in a parallel universe where networks stood up to anti-communist bullies and advertisers and sponsors supported programs on the basis of creativity and audience enthusiasm rather than conformity to a formulaic Americanism.

Blacklisted women like Ruth Gordon, Madeline Lee Gilford, Revere, Royle, Webster, and Winkler continued to work in theater because the stage remained “the last refuge for people who could no longer work in film or television or radio.”41 As New York Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson put it, “Broadway is not susceptible to domination by rational businessmen. Broadway showmanship is a local foible rather than a national exploit.”42 In 1950, actresses Marsha Hunt and Hilda Vaughn starred in Margaret Webster’s production of George Bernard Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple.43 As late as 1959, Berg starred in A Majority of One, an interracial love story about a Japanese widower and a Brooklyn widow, for which she won a Tony Award for best actress. Although minus the exposure afforded by appearances in film and television, it remained “hard to get the few well-paying jobs in the New York theater,” as Kate Mostel put it; a very few even managed to return to Hollywood in the late 1960s, like Ruth Gordon, who starred in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Harold and Maude (1971).44

At the height of the blacklist some progressive women writers found work in Europe, such as Vera Caspary and Norma Barzman, wife of blacklisted journalist, screenwriter, and novelist Ben Barzman. The post-blacklist career of their colleague, producer Hannah Weinstein, provides a compelling illustration of the work that this capable generation of women was prevented from doing in the U.S. Although she was not one of the Broadcast 41, Weinstein played an important role in the history of the blacklist and, indeed, in the history of progressive media production. A former advertising executive and supporter of Henry Wallace’s failed 1948 presidential campaign, Weinstein left the U.S. before the Hollywood Ten were jailed and moved to London, where she founded the television studio Sapphire Films.45 Norma Barzman credited Weinstein with saving “many exiled blacklisted Americans,” over the course of a decade employing at least twenty-two American writers living in Europe and the United States who could no longer find work in the U.S. because of the blacklist.46

Although Weinstein’s Sapphire Studios is perhaps best known for inaugurating a costume-drama craze in England, with The Adventures of Robin Hood and Lancelot, she is also credited with producing an innovative crime series written by blacklisted writers Walter Bernstein and Abraham Polonsky. Colonel March of Scotland Yard, as scholar Dave Mann documents, featured “the celebration of professional and resourceful women,” including “murderesses,” a “plucky female undercover insurance investigator who corners the villain singlehanded,” and an anthropologist and documentary maker who joins an Everest expedition.47

Under Weinstein’s direction, Robin Hood in particular proved a powerful vehicle for progressive political views. In this show, blacklisted authors like Ring Lardner, Jr. and Adrian and Joan LaCour Scott explored themes of betrayal and social justice that were very much on their minds. In an episode written by the Scotts, for example, titled “The Cathedral,” the mason in charge of building the structure is falsely accused of “being a tool of an international conspiracy, anti-Church and anti-Christ.”48 In “The Charter,” also written by the Scotts, Robin located a lost document that protected the rights of progressive nobles who wanted to reform the aristocracy and redistribute land and other forms of wealth.49

Such themes were, of course, too subversive for anti-communists. Adrian Scott told a friend that the climate in the U.S. had become such that, “Today, when you characterize the rich as stingy, this is subversive.”50 Ilana Girard Singer, whose activist father was blacklisted in northern California, recalled that her “beloved Robin Hood had been banished from some school libraries because Senator Joe McCarthy called it ‘communist doctrine.’”51 Robin Hood’s considerable success in England allowed it to breach the blacklist in America in 1955: the show was broadcast on CBS from 1955 to 1960.52 Still, Rod Erickson, who handled television spots for Young & Rubicam at the time, said that when he bought the show for American sponsor Johnson & Johnson, “General Johnson asked to see me. He said, ‘Why are we sponsoring that commie show?’”53

Some blacklisted writers used pseudonyms or fronts (people who would be the front person for scripts written by blacklisted authors) to continue writing for television, mainly in work they completed in the medium’s margins, in time slots and genres considered less valuable and culturally important, and thus less likely to attract the attention of anti-communists.54 According to Adrian Scott, “when things were bad for me I did not, as most did, look for the best programs on the air—which everybody hoped to write for. I looked for the worst.”55 Progressives like Scott and his wife Joan left evidence of their perspectives not in what were considered the best programs on the air (those that ran during prime-time viewing hours before the advent of home recording technologies: 7–8 through 11 p.m.), but in programming deemed less valuable.

Science fiction writer Judith Merril later observed that for women writing fiction in the 1950s, science fiction was “virtually the only vehicle of dissent available to socially conscious authors working in a historical moment marked by political paranoia and cultural conservatism.”56 In television, children’s programs and soap operas proved to be similar havens for women writers and performers affected by the blacklist. Soap opera writers Irna Phillips and Agnes Nixon had been telling progressive stories in the devalued regions of daytime television and soap operas well before the blacklist. Unlike the Broadcast 41, these women continued to work in soaps for decades to come. Like Gertrude Berg, Phillips created, wrote, and starred in episodes of her first program, Painted Dreams, a show that explored shifting gender roles in the context of intergenerational conflict. Phillips’ protégée, Agnes Nixon, went on to write her own brand of distinctive storylines about class, race, ethnicity, and national identity. Doris Hursley (daughter of Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s socialist mayor, Victor Berger), who along with her husband, Frank, created the soap opera General Hospital, was known for tackling the kind of controversial topics that attracted anti-communist attention in prime time. After the blacklist, women like Phillips, Nixon, and Hursley hired actresses who had been made otherwise unemployable by anti-communist campaigns against them. Anne Revere starred in The Edge of Night and Search for Tomorrow; Selena Royle in As the World Turns; Meg Mundy in The Guiding Light; and Louise Fitch in Paradise Bay and General Hospital.57

Like soaps, children’s programs also hired progressive writers who could not find work in prime-time television. For blacklisted writers Joan and Adrian Scott, the children’s show Lassie (1954–73) became the couple’s most reliable source of income.58 Wryly acknowledging the limitations of this work, Adrian Scott told a friend, “For several years Joan and I, individually, wrote programs for the LASSIE series. At one point we were considered the best LASSIE writers they had! Because, as Joan says, we are house broken and barked well.”59

Nonetheless, as Joan Scott observed in her unpublished autobiography, they appreciated the show’s emphasis on “humane, caring values—not the violence and shallowness characteristic of so many of the TV programs on the air.”60 And Lassie’s wagging tail concealed a rebellious streak. Lassie often referred to humanitarian work recognizable as progressive, like an episode where a priest adopted an orphaned boy whose martyred parents had worked with him in South America “to improve crop yield among peasants.”61 The show departed from the 1950s suburban ideal in significant ways, evoking the lost world of the New Deal rather than the shimmering consumerist settings of the 1950s. Originally, it featured a widowed mother, who lived with her elderly father on a farm. Over the years, Lassie’s families frequently refused to conform to the suburban norm, expanding to include a series of young adopted boys, forestry workers, and finally the inmates of a home for troubled children. In an early episode of the series, Lassie tried to prevent Timmy’s mother Ruth from replacing their old icebox with a refrigerator because the dog feared that friendly iceman Mr. Cuppy would lose his job.62 Although adoptive dad Paul Miller chided Lassie for being “a reactionary” because of her attachment to tradition, in this case (as in many others), Lassie’s empathy was the lesson of the day.

Where Cold War programming used the non-human world to defend patriarchal nuclear families and the subjugation of the natural world, Lassie offered a different perspective, hinting at an incipient animal rights attitude. Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom presented a vision of the non-human world where lions, crocodiles, and hippos were each in their turn cast as rulers and kings in a natural order of domination. But Lassie and Daktari (another children’s program the Scotts wrote for) referenced a different natural order of things, one that echoed with the cadences of progressives’ political vocabulary, refusing to see man’s domination of the non-human world natural or just. Forestry rangers in an episode of Lassie eschewed the competitive language of Cold War representations of nature, instead commenting approvingly on eagles’ collaborative approach to parenting:

To the extent that scripted children’s programming featured values like sharing, peace, and respect, it may have been because of writers like the Scotts, the ubiquitous Ruth and Rita Church (credited for writing several episodes of Lassie between 1958 and 1960), the Hursleys, and other progressives who wrote for shows like these, and whose perspectives remain to be excavated. Similarly, the evolution of ideas on soap operas—and the fact that soaps historically addressed controversial social ideas in many cases decades before other television genres did—suggest how people like the Broadcast 41 might have influenced the stories television told about American ways of life. Because of the blacklist ideas like theirs were relegated to the margins and, as Adrian Scott put it, “ideas, new, good, provocative, daring ideas, the very lifeblood of the industry have been denied to creators.”64 Writer Eileen Heckart poignantly expressed the frustration of having to write within the grooves of acceptability established by the blacklist. “Honey,” she asked an executive, “can’t you get me out of the kitchen? I’m so sick of making the cocoa for Mama and the eggs for Dad.”65

❖ ❖ ❖

You will ask me one day how I came to write about this. The answer is for two years I took care of my son as both father and mother. I was nag, shrew, housekeeper, shopper, and unsuccessful writer. Prior to this I’d had the usual exposure of a progressive to the woman question. But it was all very unreal until I was forced by circumstances into the role of a woman in the house. My abstractions became concrete. From fellow traveler, I became hardcore militant associate of the movement. I came away with a healthy respect for what women are forced to endure in this society. I concluded that real equality as in every other movement toward equality will be won by the oppressed with very little help from the outside. I only hope when the revolution takes place and when the inevitable excesses follow that, as I am led to the guillotine, one woman will remember I wrote Ellie.

Adrian Scott (screenwriter and film producer)66

I felt you do not have to be white to be good. I’ve spent most of my life trying to prove that to people who thought otherwise. Yes, it was pointed out that I might be useful to the group by passing. But to pass, for economic or other advantages, would have meant that I swallowed, whole hog, the idea of Black inferiority. I did not think up this system, and I was not responsible for how I looked. So I said to myself: I’m a Black woman and proud of it.

Fredi Washington (actress, journalist)67

Despite the blacklist, what Adrian Scott described as “ideas, new, good, and provocative ideas,” the result of the rich perspectives the Broadcast 41 brought to their work, persisted in the nooks and crannies of historical memory. In archives, interviews, letters, and other autobiographical writings those who were blacklisted left concrete evidence of their ideas. This book began with such an example: Adrian Scott’s Ellie, a story based on his perspectives as caregiver to a son with significant mental health challenges and the ways in which his experiences transformed him into a “hardcore militant associate” of the movement for women’s liberation.

Ellie is just one example of programs that progressive cultural producers with feminist sensibilities had hoped to create in the years after war’s end. Shirley Graham envisioned a whole range of transformative projects (Figure 6.3). In the late 1940s, she was hard at work on a new novel, a book about white journalist Anne Newport Royall, a woman who was, by some accounts, the first woman journalist in the U.S., an abolitionist who published a newspaper about political corruption in Washington, DC from 1832 to 1854. Occupying Royall’s perspective, Graham used the experiences of people of color to contextualize Royall’s life and explore the relationships among race, class, and gender that shaped it. Describing Royall’s adoption by Native Americans after the burning of the settlers’ stockade in western Pennsylvania, Graham contrasted Royall’s childhood and adolescence spent among Native Americans with the barbaric sexism and racism she encountered when she reentered white society:

And there had been men—soft, flabby men who stretched out pudgy hands in her direction. Anne knew her body was beautiful; she and Pelo and the other Indian boys and girls had swum the Mushingum many times, in her growing-up summers, naked and free. She had known a lot about birth and death and mating, but she … had never been pursued for her body until she came to Sweet Springs.68

The contrast between the matter-of-fact sexuality that she had experienced among Native Americans and the predatory white men who pursued her sexually challenged the conventional tropes of barbarism and savagery.69

Source: Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Instead of looking to the past for inspiration, Vera Caspary was preoccupied with a century that had witnessed huge changes for many women. Reflecting this, she proposed a television series in the 1950s about a family in the midst of similar social changes, creating stories distinct from the bland domestic intrigues of family sitcoms and the heroic frontier protection scenarios of Westerns. Titled The Private World of the Morleys, Caspary’s proposal for the series revolved around what Caspary described as “an acute inspection of the most urgent questions of our time.” These questions included what happens to the family’s matriarch once the children have grown up; how the family’s patriarch ages and experiences the loss of male power in “a world that has gone past him”; and the youngest daughter’s struggles to enter the sexist profession of surgery.70 A woman entering the male-dominated world of surgery had appeared on radio in Joyce Jordan, Girl Intern and Joyce Jordan, MD, but many of the issues raised in Caspary’s proposal for The Private World of the Morleys did not air again on prime time until the series Family premiered in 1976.71

Progressive performers expressed their frustration at the limited roles available to women and people of color through their criticism of stereotypes. They hoped someday to play the kind of roles that writers like Berg, Caspary, Graham, Hellman, and Parker wrote about women and people of color as makers of history and political agents. In 1945, when asked by a writer from Ebony magazine what roles she dreamed of playing, Lena Horne responded, “I could play some of the Negro characters of history, like Sojourner Truth, the Civil War abolitionist, or maybe I could play the part of the Negro WAC of today.”72 Actress and writer Fredi Washington kept copies of film scripts that presented African Americans as heroes rather than as servants or comics, like Dorothy Heyward’s script about Denmark Vesey (who led a rebellion against white supremacy in Charleston, South Carolina in 1822) and a script by Paul Peters about Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion.73

Denied opportunities to appear in programs that featured African Americans as full citizens and multi-dimensional human beings, African American performers mainly landed guest appearances on variety shows hosted by white men and women. Performance studies scholar Shane Vogel maintains that performances by women like Horne on these shows actively resisted “the circumscribed roles available to black women on the Jim Crow stage.”74 Horne, Scott, and Washington fought for better roles for African Americans until the end of their lives, but these efforts were stalled by the blacklist. Subsequent generations of performing artists thus had limited abilities to shape television’s representations of race and racism.

When it comes to television, it can be easy to overlook actors’ power not only to incorporate defiance and resistance into their performances, as critics argue Louise Beavers did in her performance in Imitation of Life (1934), but to influence writing as well. Fredi Washington, Beavers’ co-star in Imitation of Life, recalled that she had “to fight the writers on lines like: ‘If only I had been born white.’ They didn’t seem to realize that a decent life, not white skin, was the issue.”75 Performers too could affect what appeared on screens, which perhaps also explains the G-Man’s determination to remove progressive actors from television and movie screens.

❖ ❖ ❖

I did a good deal of radio work from time to time—I always enjoy this, providing the material is worthwhile. If I were not so insistent on that point I should undoubtedly have worked a great deal in this medium, but unfortunately, the good programs are few and far between, and I have a foolish distaste for entering people’s homes bearing unworthy gifts.

Eva Le Gallienne (theater producer, actress, director, author)76

There are all-girl stations on which everything is done by what once used to be called the weaker sex—even the technical jobs of operating cameras and light.… The first metropolitan station to go all-girl was WNEW-FM, New York, which celebrated the Fourth of July, 1966, by announcing that four beautiful and intelligent-sounding young women would divide the station’s broadcast hours—10 a.m. until midnight.

Robert St. John (broadcaster and journalist)77

The Broadcast 41 made art and culture that criticized racism and sexism. But progressive content was not the only casualty of anti-communism in television: progressive media criticism was as well. Criticism plays an often unsung role in improving media content. New and innovative content generates criticism and discussion. Criticism and discussion, in turn, can shape and change creative ideas. As Farah Jasmine Griffin points out in relation to black feminist literary criticism, criticism played a vital role in providing a context for, and directing attention to, African American women’s writing.78 In the case of theater and literature, progressive media criticism—by producers, actors, writers, and journalists—educated readers about stereotypes, pushing one another and the industry to change and innovate. Criticism served as midwife for progressive content, facilitating progressive media production. Without criticism, traditions do not get invented, representations do not change or become more inclusive.

The Broadcast 41 were born critics. As people who had never experienced being at the centers of industrial, political, or cultural power, the Broadcast 41 were inclined to be critical of media that demeaned and excluded them. Fredi Washington used her entertainment column in The People’s Voice to criticize Hollywood’s representations of African Americans, as well as the exclusion of African Americans from jobs on film and broadcast crews. In her column, she pledged to fight so that “the Motion Picture Industry and the radio shall become more conscious of the tremendous revenue paid by Negroes for their products and be made to handle with regard and respect, all material dealing with and pertaining to Negroes.”79 Lena Horne similarly used her own People’s Voice column to criticize the radio industry for discrimination against African Americans in representations and hiring practices alike. Drawing on her experiences, Horne described how radio programs were written so as to prevent her “from having a conversation with any of the principals.”80

Anti-communists knew that criticism had the power to shape and change representations, which explains why anti-communists were so defensive about Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind and its film adaptation. Just as the FBI and the American Business Consultants connected progressive literary and political criticism—especially of white supremacy—with communist influence, so they attacked those who dared criticize the novel and film versions of Mitchell’s tribute to the Confederacy, describing such critics as communist operatives. Anti-communist journalist and star HUAC witness Howard Rushmore, in fact, said that he left the Communist Party in 1939 because members demanded he address Gone with the Wind’s racist sentimentality in his review.81

The best of progressive criticism and research contains within itself a utopian germ: it wants what it criticizes to be better, it seeks to use the results of critical analysis to improve and expand content and to shift perspective. Shirley Graham described how her own research caused her perspective to change. As she researched her novels on Jean-Baptiste Pointe de Sable, the Haitian founder of Chicago, Pocahontas, and Anne Newport Royall, Graham wrote that she “became aware that this was not as narrow a problem as I had thought. It wasn’t only the Negro. I began to realize that as I was trying to widen the horizon of other people, my own horizon was widening.”82 By suppressing progressive criticism, the blacklist denied producers and television the means to grow and evolve, especially when it came to long repressed issues of race, gender, and nation.

❖ ❖ ❖

My method is perhaps an old-fashioned one, based perhaps upon an old-fashioned belief … that the American people do not need “protection.” I have an immense respect for the intelligence of the American people. I believe it to be at least as great as mine, and at least as great as that of any official whom we may elect to carry out the arduous tasks of government.… I believe that you cannot really believe in democracy without trusting the intelligence and integrity of our fellow-citizens.

Anne Revere (actress, trade unionist)83

“There Was Once a Slave” not only told me the heroic story of Frederick Douglass but it told me something about America that I will never forget. America is a great country, but if we are to build from the foundation our forefathers laid, and set an example for the rest of the world, we must have complete freedom within our own boundaries. Your book strengthened that foundation and gave me something to remember and live by through this time of hatred and war. Thank you Miss Graham, thank you very much.

Susan Welch (7th Grader)84

The blacklist further affected the future of American television by reinforcing racist and sexist stereotypes about audiences said to object to the content preferred by anti-communist masculinity. As the FBI’s media criticism shows, anti-communists viewed audiences made up of anyone but white men as gullible and undiscriminating masses, a view the television industry came to share. Persuaded by anti-communism that white male audiences alone had value, the industry pitched prime-time programming and content to them, using the bottom line to justify this.85

Because they were members of audiences considered less valuable and thus less intelligent, many progressives approached their own audiences very differently from studio heads and executives. They knew that audiences enjoyed progressive ideas from their work in theater and music and were much less likely to accept on faith what anti-communists and industry moguls said about mass media audiences. Disparaged by industry moguls and anti-communists as both producers and audience members themselves, they took umbrage at this treatment, creating content that reflected a more respectful view of audiences and an awareness of media as tools for educational and intellectual advancement.

The Broadcast 41 openly expressed frustration with the industry’s bigoted attitudes toward audiences. Lillian Hellman complained of her work at MGM that “you had to write the kind of idiot-simple report that Louis Mayer’s professional lady storyteller could make even more simple when she told it to Mr. Mayer.”86 Hellman knew that the “idiot-simple” intelligence attributed to audiences often reflected executives’ own tastes and attitudes toward the people for whom they were producing mass culture. Many of the Broadcast 41 suspected, like Hellman, that these “lady storytellers” were really pandering to Mayer’s own tastes, tastes projected onto audiences that had no means other than fan letters locked up in corporate archives to register their actual feelings about content. The stories the industry told, that is, had to be stupid enough so Mayer would not feel threatened by them, a point that speaks volumes about executives’ investment in the idea of stupid audiences rather than the realities of audiences.87

In this, Hellman shared Vera Caspary’s belief that audiences were more intelligent than Hollywood “big shots.” “I have sat in movie houses in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Marshalltown, Iowa, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Encinitas, California,” Caspary wrote, “and I have never found any audience as dull as the big shots who attend story conferences solemnly believe.”88 Hellman contrasted theater’s and film’s attitude toward audiences and found the latter wanting. Where theater offered the “ability to present an idea for the consideration of intelligent audiences,” in film, executives “wouldn’t know an idea if they saw it … and if by any chance they should recognize it the film people would be frightened right out of their suede shoes.”89 Anne Revere similarly thought audiences were made up of intelligent and educable citizens, capable of interpretation and independent thought. Unlike anti-communists, who thought audiences needed to be protected from subversion and controversy, Revere maintained “that the American people are not easily gulled.”90

Progressive women producers, directors, writers, and performers assumed their audiences and fans to be active and intelligent interpreters of culture. Lisa Sergio spoke to news listeners she considered her intellectual equal, people who shared her interest in global politics and the histories of international political struggles. Popular radio show host Mary Margaret McBride; soap opera writers and producers like Irna Phillips and Elaine Sterne Carrington; and sitcom giants like Gertrude Berg were not members of the Broadcast 41, but their successes in the industry confirm that progressive women spoke to their audiences differently than did the industry as a whole. Historian Susan Ware says that McBride—whose work in radio began in 1934 and spanned a period of nearly forty years—was unique in her respect for her female listeners. According to Ware, this characteristic “endeared her to female listeners tired of being patronized by radio personalities and advertising executives who assumed that all they were interested in was recipes and curtains.”91

Like McBride, Gertrude Berg and radio and television writer and actress Peg Lynch listened carefully to their fans, reading and responding to the many thousands of letters they received over decades of work in broadcasting. For them, audiences and fans were not abstract, faceless multitudes, but people—often women—who wrote them thoughtful, intelligent letters. In these letters, viewers and listeners took exception to the industry’s definition of what was popular and complained, as one fan did to Peg Lynch, that “not all us housewives dropped everything to listen to [Arthur] Godfrey. Occasionally he had interesting guests. Then the program was worth taking the time to watch. But, our time is too valuable to waste on programs featuring pop-tune singers, quiz shows, animated soap operas and off-color quips.”92 Berg and Lynch relied in turn on their audiences for support, mobilizing them in letter-writing and telephone campaigns when networks threatened to cancel their popular programs. The relationships between these stars and their listeners and viewers—relationships that remain to be studied and documented—were intimate and meaningful.

Shirley Graham’s work in developing a national television system in Ghana shows just how radical progressive women’s ideas about audiences could have been, unfettered by the collusion between anti-communism and the industry’s own sexism and racism. After years of state surveillance and harassment—in 1954, Graham wrote to a friend, “McCarthy’s hound dogs snarl at our heels, prowl about our doors and sniff at our windows”—Graham and Du Bois sought refuge in Ghana, where President Kwame Nkrumah asked her to help establish the country’s first national television system.93 Eager to reach underserved and unrepresented audiences with new media, Graham envisioned a non-commercial television system that served the educational and public health needs of Ghanaian culture rather than those of Western, corporate elites. Drawing on her own experiences of an educational system that denied histories to people of color, Graham planned to build an infrastructure for indigenous television production, establishing programs to train writers for the new medium.94 In order to generate content for television news, she wanted to “send reporters into every part of Ghana,” so that “the inhabitants of seldom-visited villages of the interior will know, seeing themselves on the screen, that they are not forgotten.”95

Like Graham, other members of the Broadcast 41 knew it was important for people to see themselves represented on screen and to understand they were not forgotten. And despite anti-communists’ assertion of some mass audience that hated progressives so much that they would boycott shows that featured them or the themes they were associated with, the Broadcast 41 had much evidence that suggested otherwise. In their haste to demonstrate their loyalty to anti-communism, media industries elected to overlook this evidence. For example, when stage director and actress Margaret Webster first began discussing a production of Othello starring African American actor Paul Robeson in the late 1930s, she was told that it would be a box office disaster. In the end, she financed the production largely on her own. She produced the play in 1943, with José Ferrer and Uta Hagen cast alongside Robeson. As Webster recalled, “in the teeth of every possible hostility and prediction of doom,” when the curtain fell on the first performance of Othello at the Shubert Theater in Manhattan on October 19, 1943, the standing ovation lasted for a full twenty minutes.96 Webster’s Othello ran for 296 performances, a record for a Shakespeare play on Broadway that stands today.97

Even within the more restrictive environment of broadcast media, evidence of interest in stories told from perspectives other than those sanctioned by G-Men was abundant. Gertrude Berg successfully spoke to audiences across the U.S. about Judaism, opting not to concede to the beliefs of the anti-Semites conjured by network and film executives to justify the industry’s anti-Semitism. Although advertisers repeatedly expressed surprise about The Goldbergs’ popularity among Jewish and non-Jewish listeners and viewers alike, over the course of the show’s long run, Berg often received more than a thousand letters a week. These letters, she later recalled, “came from all over the country, and, contrary to everyone’s belief, the majority of the mail didn’t come from the Jewish population.”98 In fact, Berg argued that the show’s successes showed how wrong the industry’s governing ideas about audiences really were:

The audience refused to be typed and from the mail I learned a great lesson: There is no way for anyone to predict what the American public is going to like, going to do, or going to say. I’ve gotten letters from priests, ministers, and rabbis, and from millionaires and paupers.… The reactions of the people who listened only showed that we all respond to human situations and human emotions—and that dividing people into rigid racial, economic, social, or religious categories is a lot of nonsense.99

The fan letters The Goldbergs received conveyed a portrait of a listening public inspired not by the desire to see only their own images on television screens, but by what they saw as shared American values of curiosity, education, and inclusion.100

As these examples suggest, even within the constraints of capitalist media systems, a wider range of representational fare for far more diverse audiences could have been possible. But by threatening that so-called controversial programs would result in boycotts and plunging revenues, the blacklist allowed the industry to use the fiction of a purely economic rationale to eliminate progressive ideas. According to social scientist Marie Jahoda, who conducted a landmark study of the impact of blacklisting on the industry:

Apparently many sponsors, producers, directors, casting officers, and others in the industry go along with the blacklisting of accused individuals even though they consider the practice to be foolish or wrong. What induces them to go along with the demands of the blacklists is the argument that an objectively small, but economically important portion of the audience might take offense and refrain from buying an advertised article if the industry did not go along.101

It did not matter that there was little evidence that audiences would boycott any of the limited content on the new medium’s three networks: anti-communists brandished fear of boycotts as if these were inevitable.

Because control of what appeared on television lay in the hands of network oligarchs, there was no feedback loop for fans, many thousands of whom wrote letters to networks, sponsors, and advertisers when programs like The Goldbergs were cancelled. Progressive audiences’ objections went unheard and, like the Broadcast 41 themselves, have largely been forgotten. As for the popularity of progressive theater, it was dismissed as elitist East Coast fare that would not play in Peoria, as an old adage from American theater went, much less on the conservative landscape of television. Aided by the blacklist, the industry’s concern with white audiences and silent majorities created representational redlining in television and then institutionalized it.

Decades after the publication of Red Channels, television writer and producer John Markus described the “Network’s oversensitivity to special interest groups” as emerging during the 1950s.102 But the vagueness of Markus’ claim is deceptive. The audiences anti-communists cared most about were those whose views could be used to channel their own political interests. The audience that television was most concerned with was an audience that lived down to anti-communist expectations, best represented as people with immoveable attitudes toward people of color, women, immigrants, and those less fortunate than them. This lack of belief in people’s better natures meant that television worried about offending silent majorities of audience members who affirmed anti-communist beliefs and thus white supremacy, misogyny, and xenophobia.

In fact, the blacklist institutionalized oversensitivity to anti-communist groups, whose threats to picket and boycott television programs employing black- or gray-listed progressives were incorporated into the common-sense thinking of the industry. Long after the era of direct sponsorship was over, producers and writers self-censored to avoid any hint of controversy—to avoid “anything that might bother people,” in Gertrude Berg’s words.103 Anti-communists justified this censorship in the name of an audience they had in large part created, helping to ensure that until the late 1980s, women and African American, Asian American, Native American, and Latinx writers, directors, and actors would continue to “struggle for drama,” as journalist Kristal Brent Zook puts it, in order to create and star in roles in which they could be represented as multidimensional human beings.104

It was, of course, perfectly acceptable to abuse women and working-class people, through humiliating stereotypes that persist today; to insult people of color, through images that represented them as lazy, licentious, and inherently criminal; to disappear immigrants from the representational spectrum; and to offend thoughtful people as a whole. The blacklist caused the industry to affirm intolerance under the guise of fighting East Coast liberalism, a geography of politics it considered, after all, only a transfer or two away from Red Square.

❖ ❖ ❖

When I saw you [Ruth Gordon] in “Years Ago” it gave me the courage to really try and see if I too couldn’t do as you have done.

Cynthia Allen (actress)105

And then I went to Chicago where I was sort of drawn into the Federal Theatre as Supervisor of the Negro Unit of the Chicago Federal Theatre. Now this was purely sort of accidental when I got to Chicago they were getting ready to dismiss and throw out all the people of the … Negro Unit because they hadn’t been able to do anything. And in a burst of indignation, I went down and talked to the director of the Chicago Federal Theatre and told them they didn’t know what they were doing. That these people were the most talented and most gifted of anybody that they could possibly have in the Federal Theatre and they evidently just didn’t know how to handle the situation. Well he acknowledged they never had anybody but whites over this group, and when I left, getting ready to go back to my own job in the south just as I was about to leave, I got this telephone call and he offered me the job—“Okay,” he said, “so you know so much about it, well you just do it.”

Shirley Graham (musician, writer, civil rights activist)106

In addition to denying generations of producers the means to create and share stories about the diverse perspectives of the people who live in the Americas, past and present, the blacklist also eliminated a generation of industry leaders, teachers, and mentors who might have transformed the climate within media industries. Media studies scholar Kristen Warner reminds us that “creativity is not a mystical, inspirational act.” Within media industries, she observes, creativity “is a learned and socialized behavior.”107 After the blacklist, writers, directors, producers, and performers were socialized within a work culture whose organizational hierarchies not surprisingly looked a lot like the world reflected on television screens, with white men firmly in charge, white women in supporting roles, and people of color—when they appeared at all—as servants, subordinates, or deviants. The work cultures that resulted from the blacklist reenergized practices of discrimination against women and people of color that had been subject to increasing scrutiny during World War II. Those most likely to oppose discrimination were either fired or silenced. The blacklist eliminated the few women who had advanced to leadership positions within the industry, thereby also wiping out opportunities to learn from a generation of talented progressive women. The events of the blacklist era taught women, as one FBI informant put it, “that to be good citizens they should stick to their knitting and keep their noses out of politics.”108

Forms of alliance and mutual support were vital to women’s advancement and survival in media industries like television, as well as to nurturing progressive attitudes toward women and people of color among newcomers and socializing them in ways that countered media industries’ racism and sexism. Many progressive women got their breaks in media industries because of these networks. Vera Caspary’s screenwriting break came about because of a chance encounter at the Algonquin Hotel with Laura Wilck, a story editor for Paramount Pictures, who gave the jobless and nearly broke Caspary a $2,000 advance to write the script for the film The Night of June 13th.109 A generation of talented progressive writers and actors passed through the doors of The Goldbergs, including Abraham Polonsky, Garson Kanin, Louise Beavers, Fredi Washington, and Joe Julien. Ruth Gordon’s papers at the Library of Congress are full of thank-you notes from aspiring actors who turned to the star for advice and support. Mary Margaret McBride got Stella Karn her first job in radio as business manager for her show; Karn’s “first act” was to get McBride the salary increase she deserved.110 Actress Donna Keath worked with others to found Stage for Action (SFA) in 1944, a theater company providing community for progressive cultural workers.

Horne and Scott found comfort and sustenance in the company of other black singers and musicians, many of them women, such as Mary Williams, Billie Holliday, and Lil Hardin Armstrong. When Lena Horne decided that she wanted to resume her career after having two children, Fredi Washington set up an audition for her and the Negro Actors Guild of America paid for Horne to travel from Pittsburgh to New York City.111

In 1950, many of the Broadcast 41 were well established in media and creative industries. They were trailblazers, with their own networks of sustenance and survival. Wartime labor shortages had given them significant experience in their unions. They were leaders as well in industry and community-based philanthropic efforts. Actress Selena Royle formed the Actors Dinner Club, which provided free dinners to needy actors. She was a sponsor of the Stage Door Canteen, which offered food and entertainment for military personnel during World War II in New York City. A journalist described Marsha Hunt as “one of Hollywood’s first celebrity activists.”112 In 1938, Hunt founded the Valley Mayors’ Fund for the Homeless to advocate for shelters and services in the Los Angeles area. After the blacklist, she became involved in humanitarian issues, opening the first United Nations Association offices in Southern California and working closely with the World Health Organization and UNICEF. Hunt served as a board member of the Community Relations Conference of Southern California and founded the Southern California Freedom from Hunger Committee, remaining an advocate for progressive social change into the twenty-first century.113

Members of the Broadcast 41 also founded and led organizations providing support for immigrants and people of color across media industries. Pianist Ray Lev told the FBI when they questioned her that “as a member of a minority group she believes her responsibility is to aid minority groups and foreign born.”114 She fulfilled this responsibility through hundreds of fundraising performances on behalf of groups working on civil rights for African Americans and the foreign-born.

When the intransigent racism of the industry and the blacklist prevented them from contributing meaningful content to media, the Broadcast 41 became leaders in creating alternative venues for education and celebration of cultures excluded from anti-communist versions of Americanism. Margo—Mexican-American dancer Maria Margarita Guadalupe Teresa Estella Castilla Bolado y O’Donnell Albert—founded Plaza de la Raza in 1970 with trade union activist Frank Lopez in East Los Angeles. A cultural center that provided arts education programs to children, adolescents, and adults, Plaza de la Raza continues to operate today, more than thirty years after Margo’s death in 1985, its mission even more urgent in light of continued defunding of arts education throughout the U.S.

In addition to using their stardom to draw attention to progressive causes and modeling forms of citizenship for those aspiring to work in the industry, progressive women and men served as mentors for those who, often like them, were disenfranchised and marginalized within media industries, especially African Americans, who were barred from most unions until the 1950s. In 1937, along with Bill Robinson, Noble Sissle, Duke Ellington, and W.C. Handy, Fredi Washington co-founded the Negro Actors Guild of America (NAGA), a benevolent association that provided support for performers during the Depression. Washington served as executive director and secretary, overseeing NAGA’s day-to-day operations.115 Graham’s Chicago Negro Unit supported work by other writers of color, often gambling on plays by black writers dismissed as too risky by white producers. Graham’s was the first unit to stage a production of Theodore Ward’s Big White Fog (1938), a play about political tensions between reform and revolution in the life of one black family and a play that white critics predicted would cause a race riot.

Existing networks had been torn apart by the blacklist in the 1950s. Anti-communists had always been clear in their intent—to dismantle networks of those critical of them, thereby eliminating dissent of all kinds. “All those people in their 40s, 50s, and 60s,” blacklisted actress Lee Grant remembered, who “had made names for themselves were crushed and never came back.”116 The destruction of this pipeline prevented the transmission of experience and information from one generation of progressives to the next. The American Business Consultants’ and the FBI’s attacks on progressive networks in broadcasting show that anti-communists understood the power of networks of mutual respect and support among women, people of color, and other progressives and took deliberate steps to destroy them.

Buoyed by the civil rights movement and the easing of the blacklist in film, in the late 1960s, blacklisted producer Hannah Weinstein joined a group of black and Puerto Rican directors, producers, actors, and writers that included Ossie Davis, James Earl Jones, and Rita Moreno to found the Third World Cinema Corporation, a minority-controlled independent company that planned “to produce feature films and train minority group members in the film and television fields.”117 Third World Cinema went on to produce Greased Lightning (1977)—about the first black stock car racer in the U.S.—and Stir Crazy (1980)—a buddy film with a multiracial cast and a gay character. Both films starred comedian Richard Pryor and were directed by African American directors (Michael Schultz and Sidney Poitier).

The redaction of these women and the generations who might have followed created a persistent silence in television around race, nation, gender, and other aspects of people’s lives considered controversial by anti-communists. Notwithstanding the popularity of Berg’s The Goldbergs in the 1930s and 1940s, and even the popularity of less progressive representations of immigrants like Life with Luigi (1952), immigrant life seldom appeared on television after 1950, because anti-communists understood these representations to be as subversive as representations of black lives. In fact, after the 1950s, immigrants reemerged on entertainment programming only by way of the metaphoric aliens of ALF (1986–90), Mork and Mindy (1978–82), and Alien Nation (1989–90), and immigrants from fictitious countries, like Balki from Perfect Strangers (1986–83). Even in the first decades of the twenty-first century, stories about immigrants and their families remain broadly confined to sitcoms like gay Iranian American television writer and producer writer Nahnatchka Khan’s Fresh Off the Boat (2015–), with prime-time dramas still dominated by the native-born.

Representations of race that dared to question white supremacy—even if only by virtue of featuring non-stereotypical black characters—also disappeared from prime-time line-ups as a result of the blacklist. Progressive stars like Gertrude Berg, Milton Berle, and Eddie Cantor had challenged the color line in television before 1950 and showed every intention of continuing to do so, while writers and producers like Shirley Graham and Hannah Weinstein demonstrated their ability and desire to create and support the work of people of color in media industries. But after Hazel Scott’s show was cancelled in 1950, television did not feature another African American as host of a variety show until The Flip Wilson Show premiered on NBC in 1970, twenty years to the day that Hazel Scott had given her defiant speech to the HUAC. Today, Scott’s groundbreaking show remains largely forgotten: the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC identifies The Flip Wilson Show as the first variety show to star an African American.

Female characters who defied the formula approved by anti-communists appeared only sporadically, mainly, as television historian Elana Levine observes, on soap operas and only occasionally in sitcoms like Maude (1972–78), One Day at a Time (1975–84), and Alice (1976–85), and dramas like Family (1976–80) and St. Elsewhere (1982–88). Although African American women featured prominently in anti-communist-inspired news stories about welfare and poverty that blamed them for all manner of social woes for the last twenty-five years of the twentieth century, entertainment programming all but ignored their presence, save for short-lived programs like Frank’s Place (1987–88) and South Central (1992) until powerful women like Oprah Winfrey and Shonda Rhimes began to change the face of American television.118

Because media industries are so risk-averse, the suppression of stories about immigrants, people of color, women, and working-class people in the 1950s had longer-term consequences for American culture. As television and film became ever more concerned about the bottom line, even as their profits increased, these industries mined their own limited archives for ideas. As Adrian Scott put it, even in its infancy television was particularly dependent on adapting “something that has been done before.”119

The industry reproduced the constraints of the blacklist in programs that revived a history the medium had itself created, presenting the 1950s as an era full of blissful cultural and social harmony, recycling its past in re-makes and spin-offs. These constraints were most visible in the main tenets of anti-communist culture: the sanctity of the nuclear family and the need for white men to protect the family from the procession of racialized public enemies presented in police procedurals and crime news. “Numerous topics had become dangerous” because of the blacklist, television historian Eric Barnouw observed: “But one subject was always safe: law and order.”120 This remains broadly true today, as prime-time programming continues to reproduce tried and true tropes of law-and-order programming that routinely feature the violent deaths of women and people of color and the valorization of the repressive power of the security state.