Christian Liturgical Music in the Wake of the Protestant Reformation

ROBIN A. LEAVER

From its beginnings in the early sixteenth century the Reformation was essentially a theological phenomenon. It began as a search for an answer to the typically medieval question: How can I be saved?1 The search revealed this question in the New Testament. But the working-out of the Reformation was more than just the posing of a theological question within a medieval framework, and more than a rediscovery of biblical thinking. More than the intellectual probing of a theological possibility unrelated to the world of time and space, the question was an existential imperative: How can I be saved, today, within the realities of the society in which I have to live and work.

Thus, while fundamentally a theological and religious phenomenon, the Reformation nevertheless had implications for every aspect of human activity. Not only affecting the structure of the Christian church, together with its liturgical forms and worship patterns, the movement also brought about changes in society at large. The Protestant understanding of the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers, the commonality of all church members,2 contributed to the transformation of medieval thinking and action. The Reformation era left in its wake new policies for education; for the governance and political life of important European cities, princely territories, and nations; for commerce in banking, printing, and publishing; the rise of both the tenant-farmer and the independent artisan; new directions in the visual, plastic, and musical arts. In all these areas of life and work the far-reaching influence of the Reformation can be clearly seen.

Admittedly, these changes had already begun to take place before the Reformation had become an identifiable movement. For example, the Renaissance in general and humanism in particular embraced a “new learning” that involved a rediscovery of classical literature in its original languages, including the Hebrew and Greek literatures of Hebrew Scripture and the New Testament. Such new learning influenced the worlds of education, politics, commerce, art, and music. Thus it can be argued, with equal validity, that the Reformation was as much conditioned by social change as it was an instrument of social change.3 Nevertheless, it remains essentially a theological phenomenon that manifested itself in sixteenth-century European society, rather than being a socioeconomic phenomenon per se.4

The liturgico-musical aspects of the Reformation were materially affected by two simultaneous and interrelated developments within society at large: changes in the social standing of musicians, and the expanding importance and influence of printing.

Sacred music in the late medieval period was largely in the hands of the clergy: choir members were either ordained priests or held minor orders. But at the beginning of the sixteenth century sacred music was beginning to move in a nonclerical direction, reflecting the changes within society at large, where the profession of musician was gaining in independent status.5 Within the Lutheran church in Germany a new musical profession developed, that of cantor, personified by Johann Walter, who had moved on to Torgau from Wittenberg in the mid-1520s and is commonly regarded as the first Lutheran cantor.6 Thereafter, the music of the Lutheran church rested securely in the hands of gifted professional musicians and composers who functioned primarily within the church. Similarly, in Elizabethan England the organists of cathedrals and collegiate chapels exercised professional leadership for the liturgical music of the English church. The climate in England, however, differed somewhat from Germany, and music as a profession became increasingly extraliturgical.7

The technological revolution that materially advanced the spread of the Reformation was the refinement of the printing press, which made possible the relatively cheap production of a vast supply of broadsheets, pamphlets, and booklets. During the first half of the sixteenth century more than ten thousand individual titles were produced in German-speaking lands alone.8 When Luther drew up his Ninety-five Theses on indulgences in 1517, they were first issued in broadsheet form in Wittenberg. Even though only three extant reprints—published in Nuremberg, Leipzig, and Basel—have survived,9 many other pirated versions must have been printed and circulated, since the Theses were being discussed in detail at major European universities, including those in England, within a matter of weeks after having been posted in Wittenberg at the end of October. A vast popular literature included the pamphlets of reformed, vernacular liturgies, as well as the broadsheets and small collections of vernacular hymns and other congregational songs.10 Thus the changes that occurred in sacred music as part of the Reformation movement, although driven by theological principles, were nevertheless inextricably bound up with other changes within European society in general.

The liturgico-musical responses to the social changes of the Reformation era in both Germany and England blended continuity and discontinuity, familiar tradition with unfamiliar innovation. Tradition provided a sense of security in a changing world; innovation, a sense of progress beyond the confines of the unchangeable past.

LUTHERAN MUSICAL RESPONSES

For some reformers, the new awareness of biblical doctrine, together with the perception of the shortcomings of the contemporary church in the light of this doctrine, led them to conclude that the Reformation must mean a complete break with everything that the church of Rome stood for, especially with its liturgy and music. Thus Zwingli had banished all music from the sanctuaries of churches in Zurich by 1525, and a generation later Calvin had reduced the music of the worship at Genevan churches to metrical psalmody sung by the congregation in unaccompanied unison. At an early stage of the reforming movement in Wittenberg, one of Luther’s colleagues, Andreas Carlstadt, was also influenced by Zwingli’s views.11 Luther dismissed this position in his preface to Johann Walter’s so-called Chorgesangbuch, printed in Wittenberg in 1524. The reformer states that he was not of the opinion that the gospel should destroy and blight all the arts, as some of the pseudoreligious [abergeistlichen] claim”—clearly a reference to Carlstadt and others like him—“but I would like to see all the arts, especially music, used in the service of him who gave and made them.”12 Music, Luther never tired of saying, is the handmaid of theology. Indeed, since music and prophecy were inextricably intertwined in the Hebrew Bible, he claimed that music is the bearer of the Word of God, the viva voce evangelii, the living voice of the gospel.13

When Luther addressed the question of liturgy and music, two elements of continuity and discontinuity operated side by side; he was at the same time a conservative and a radical liturgical reformer. His first liturgical order was issued in 1523: Formula Missae et Communionis pro Ecclesia Vuittembergensi (An Order of Mass and Communion for the Church in Wittenberg).14 His conservatism compelled him to retain most of the Latin mass, complete with its plainchant monody and polyphonic settings of the ordinary. He allowed some changes, however, such as the use of a complete psalm for the introit, the omission of long graduals, and the drastic reduction of sequences—an anticipation of the reforms of the Council of Trent later in the century. On the other hand, his radicalism led to the elimination of all references to the sacrifice of the mass, which meant that the canon was severely truncated. He left only the verba testamenti, the words Jesus used to institute the eucharist. This same radicalism influenced Luther’s choice of music for his Latin liturgy. In the traditional Roman mass of his day were two basic silences, the silence of the priest as he inaudibly recited the canon, the prayer of consecration, and the silence of the people as they attended the mystery. For Luther both silences were to be replaced by the sound of music. In place of the traditional silence of the priest, Luther directs the celebrant to chant the verba testamenti, since he understands these words not as priestly prayer spoken to God but as prophetic announcement spoken to the people, who need to hear the proclamation of forgiveness. In place of reducing the role of the people at mass to silent spectators, Luther introduced congregational song in order to demonstrate the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers and to articulate a corporate response to God’s Word.15

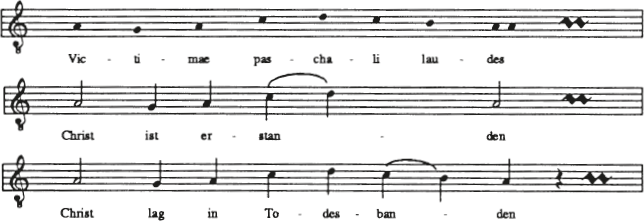

Luther and his Wittenberg colleagues specifically provided congregational hymns. In them, one can detect the twin themes of continuity and discontinuity. Some translated and adapted traditional Latin hymns, familiar to the people even though they would not actually have sung them in their original Latin form. Other hymns reworked old German folk hymns, the fifteenth-century Leisen (medieval vernacular hymns) sung after mass at the major festivals of the church year (see example 1).

However, by the beginning of the sixteenth century, some congregations sang them at festivals within the mass, in connection with the sequence of the day. In addition to these traditional elements, Luther and his friends also created new strophic texts and melodies for congregational singing, using the style of art songs of the day—the Hofweise, songs in the courtly manner—as the model. Thus the continuity of the older hymnody blended with the discontinuity of the newly created hymns.

The old and the new mingled in the same way in which hymns were performed in Wittenberg liturgy. The first Wittenberg hymnal, Walther’s Chorgesangbuch, was issued, not as a congregational collection, but as a set of part books for choral use. It contains polyphonic settings of five Latin motets and thirty-eight hymn or chorale melodies. The style simplifies choral polyphony as exemplified in the works of Josquin des Prez and others. But whereas these Catholic compositions were more extensive, employing plainchant cantus firmi (preexisting melodies used as the basis for later compositions), which are not always audible, Walter’s more concise settings are based on the Wittenberg hymn melodies, which are almost always clearly heard (see example 2).

The technique of using settings composed on preexisting melodies offered continuity; setting briefer compositions based, not on melodies of clerical monody, but on congregational hymnody provided discontinuity. These settings of Walter were sung by Wittenberg’s choir, which alternated with the congregation singing its stanzas in unison. At first, 1523–1524, the members of the congregation used broadsheet copies of the hymns, but after 1525 they had a more permanent hymnal. Thus the old practice in the medieval church of the choir answering monodic chant with polyphonic settings was replaced in Wittenberg by the congregation answering choral polyphony with unison hymnody.

This corporate expression of unanimity obviously provided a source of encouragement to the people in these times of dramatic change. In the old church, the individual Christian often felt very much on his or her own, despite the stress on the communion of the saints. Each person went to confession, received individual absolution, performed an individual penance, and individually attended mass. But the new church, which by no means underestimated the individual’s responsibility before God, found a new expression of the people’s solidarity. Together they faced the world, the flesh, the devil, and all opposition—including the Catholic church if need be!—and sang with Luther, “nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein”:

Dear Christians, one and all, rejoice

with exultation ringing,

and with united heart and voice

and holy rapture springing.

Proclaim the wonders God has done,

how his right arm the victory won.

What price our ransom cost him!

Or the fourth stanza of his Ein feste Burg:

The Word they still shall let remain

nor any thanks have for it.

He’s by our side upon the plain

with his good gifts and Spirit.

And take they our life,

goods, fame, child, and wife,

though these all be gone,

our victory has been won.

The kingdom ours remaineth.16

In 1526 Luther’s German liturgy was issued: Deudsche Messe und ordnung Gottis dienstes (German Mass and Order of Worship).17 Luther did not intend this German liturgy to replace his earlier Latin liturgy. Indeed, he expressly states that where Latin is understood—that is, in the Latin schools of towns and in the universities of cities—the basic Latin service, which could have some German elements in it, should continue. In principle Luther favored worship in the two biblical languages as well as Latin and German: “And if I could bring it to pass, and Greek and Hebrew were as familiar to us as Latin and had as many fine melodies and songs,18 we would hold mass, sing, and read on successive Sundays in all four languages, German, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.”19

The Deutsche Messe was designed primarily for small towns and villages where Latin was not understood. However, in practice, the many Lutheran church orders that were published later conflated Luther’s two liturgies and mixed Latin and German. In the Deutsche Messe congregational hymnody was increased by vernacular hymnodic versions of the ordinary of the mass, such as the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, and so forth, sung congregationally either in place of the Latin texts or after the choir had sung the Latin versions, either in plainchant or polyphony. (The latter became the usual practice.)

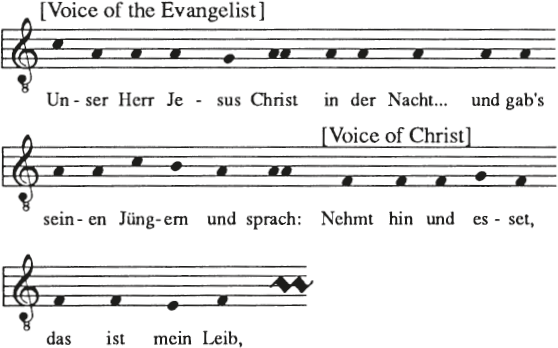

Another feature of this German liturgical order actually was the melodic formulas that the celebrant used when singing the verba testamenti. Luther had given three specific groups of lectionary tones for the chanting of the gospel, one for the words of the Evangelist, another for the words of other people within the narrative (generally within the tenor range), and a third for the words of Jesus alone (pitched lower, in the bass range). As a result, the congregation knew that the music for the words of Jesus differed from all the rest. When his words, the verba testamenti, were heard again later in the eucharist they too were to be sung to the same melodic patterns as Jesus’ part during the earlier chanting of the gospel for the day (see example 3). Thus the same basic melodic form unified the proclamation of God’s good news of forgiveness and grace, in both the chanting of the gospel and in the verba testamenti. Here is a mark of Luther’s genius: he gave practical expression to his theoretical assumption that theology and music intertwined in the proclamation of the Word, certainly a brilliant innovation connected to the past. The chant that Luther employed grew out of the long Judeo-Christian tradition of liturgical chant.20

ANGLICAN MUSICAL RESPONSES

The Reformation in England began very much in Luther’s shadow, even though Erasmus had complained as early as 1519 that English polyphonic music for the liturgy was “so constructed that the congregation cannot hear one distinct word.”21 Avoiding this lack of comprehension was to become an important principle for English Reformers, but it was Luther’s theology that grabbed their attention in the first place.

Already by 1520 a group of Cambridge theologians were meeting in the White Horse Inn in order to discover Luther’s writings. One of them, Miles Coverdale, issued around 1535 an English translation of a good many of the Wittenberg hymns, together with their melodies.22 About six years later Coverdale published a tract that called for English liturgical reform along the lines of Lutheran churches in Denmark and Germany.23 Unlike areas influenced by Saxon Germany, the theological situation in Anglo-Saxon England was more complex. Loyal Catholics maintained an allegiance to the pope in Rome; English Catholics retained traditional theology but ecclesiologically supported Henry VIII’s break with the papacy; moderate reformers, such as Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, were generally Lutheran in theological perspective, at least at an early stage of the reforming movement; and then there were the more radical reformers, such as John Hooper, who had studied in Zurich under Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli’s successor. Henry VIII himself remained with the old theology, and while he was alive the reforming movement was largely kept in check. After Henry’s death and the accession of his youthful son, Edward VI, in 1547, however, reform was openly pursued—and the four-cornered factions vied with each other for ascendancy. The old Catholics wanted the tradition to remain unchanged, but the new Catholics wanted some innovation, at least in terms of a vernacular liturgy. On the other hand, the moderate Protestants wanted to retain at least some traditional practices, but radical Protestants wanted to change everything. By and large the reformers were more influential than the Catholics in Edwardian England, and the moderate reformers outweighed the more radical, but just barely. Therefore, the first English prayer book, issued in 1549, was a compromise for everyone: it was thus simultaneously too traditional and too novel—depending on a person’s point of view.

The Anglican prayer book was, like Luther’s liturgical provisions, a blend of the two elements of continuity and discontinuity. In drawing on traditional elements, Cranmer did not confine himself to the Latin mass but developed the English vernacular liturgy against the background of Greek and, possibly even, Hebrew forms. He drew from the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, producing “A Prayer of St. Chrysostom” at the end of the English litany. Cranmer also may have been aware of Hebrew forms through Paul Fagius, the Strassburg reformer whom, with others, Cranmer invited to England. Although Fagius died shortly after having arrived in England in 1549 and therefore could not have had any personal involvement in the subsequent revision of the Edwardian prayer book, he might have provided Cranmer with some Hebrew perspectives through a pioneering book published some years before, Precationes Hebraicae (Hebrew Prayers; Isny, 1542). In the preface to these Latin translations of Hebrew prayers Fagius, the earliest Protestant to do so, drew attention to the similarities between the Jewish Kiddush and the Christian eucharist. He suggested that a knowledge of Jewish rites contributes greatly to an understanding of Christian usage.24 This fruitful comparison of the two related traditions undergirded his own view of the eucharist as a social celebration, an emphasis that is clearly marked in Cranmer’s revised prayer book of 1552. In this new form of the eucharist the isolation of priest and altar is replaced by a free-standing table in the body of the church, around which the congregation gathers as a family for this social celebration of the meal of faith.

While drawing on older liturgical traditions, Cranmer was aware also of the new developments in vernacular Protestant liturgies. He was particularly conscious of Lutheran orders, having traveled throughout Germany in around 1530. Indeed, he stayed with Lucas Osiander in Nuremberg while Osiander was working on the Brandenburg-Nuremberg church order, eventually published in 1533. In Edwardian England, Cranmer had access to a broad group of contemporary liturgical scholars: Martin Bucer, the architect of the Strassburg German liturgy, who so influenced Calvin; Valerandus Pollanus, also from Strassburg, who developed a liturgy for exile for French weavers in Glastonbury; the Polish reformer Joannes á Lasco, who compiled independent forms for the “stranger” churches in London; and Martin Micron from Ghent, who produced a Dutch version of Lasco’s liturgy for the “strangers” from the Low Countries living and working in the capital city.

Though the liturgical music of Anglicanism, like that of Lutheranism, was also made up of traditional and novel aspects, the English solution was less integrated than the German. Lutheran church music was unified in a basic tradition: monody and polyphony, organ and other instrumental accompaniment, choral and congregational music were all held together by the common thread of the chorale. By contrast, Anglicanism never expressed an unequivocal and common doctrinal position, as did Lutheranism. One of the consequences of this broader base was that English church music developed in two directions simultaneously: the choral tradition of the cathedrals and collegiate chapels, based on the multivoiced settings of the prayer book services, on the one hand; and the congregational tradition of the parish churches, devoted almost exclusively to metrical psalmody, on the other.25 Cathedrals stressed artistic celebration and parish churches emphasized the social celebration, but the same prayer book liturgy united both Anglican music traditions.

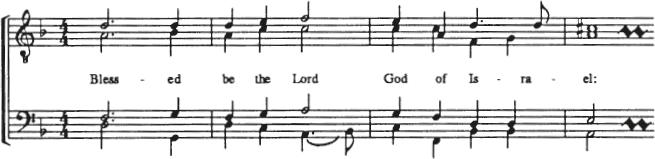

During the mid-sixteenth century, English choral, liturgical music underwent a dramatic change. Though the polyphonic settings of the Latin ordinary of the mass were magnificent, with architectonic compositions of layers of rolling sound, little attention was given to the words. But for the new vernacular prayer book service, the composers—often the same ones who had written for the Latin mass, such as Tallis and Tye—adopted an almost uniformly homophonic style with virtually no text overlap and with each syllable sounding simultaneously in each voice part (see example 4).26

There was continuity in the choral settings of the liturgy, but discontinuity in the declamatory style, created by the reformers’ desire for the sung word to be heard and understood. Indeed, Cranmer and others commended the principle of “one note per syllable” in liturgical music.27

These new, homophonic, predominantly four-part, choral settings nevertheless continued the tradition of cantus firmus composition, as exemplified in the older polyphonic masses. They were frequently based on plainchant.28 The traditional plainchant was often modified and simplified, but usually in a creative way, reflecting the different inflections and stresses of the English language when compared with the Latin.

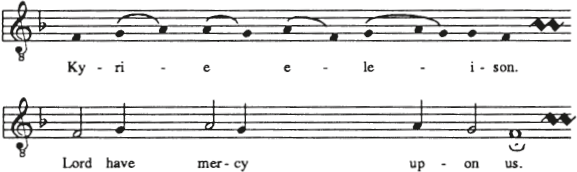

In the liturgical monody for the new prayer book liturgies a similar process can be detected in as early as The booke of Common praier noted, issued semiofficially in 1550.29 The composer John Marbeck, organist at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, developed a brilliant, rhythmically measured adaptation of traditional plainchant to match the sounds and rhythms of the English liturgical language. He often greatly simplified the traditional chant but was always sensitive to the basic integrity of the ancient monody (see example 5).

As well as adapting traditional plainchant, Marbeck also created new monodic chants, much wider in range than the traditional melodies, the two notable examples being his settings of the Gloria and Creed in the communion service, although even these are redolent of traditional melodies. Thus, for the polyphony and monody that was used with the prayer book services in cathedrals and collegiate chapels, the new was created out of the old, and the old continued in a modified form.

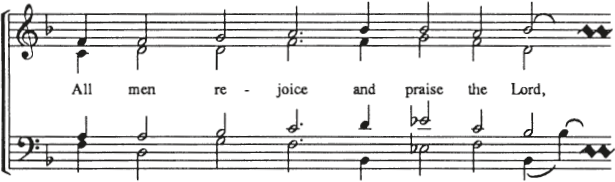

In the parish churches of English towns and villages virtually the only music for worship was the congregational metrical psalm, although some parishes in larger towns and cities maintained a choral tradition throughout the remainder of the sixteenth century (these latter, however, were exceptional). The English metrical psalm was developed by Sternhold and Hopkins during the reign of Edward VI. This early English psalmody was apparently, like the choral tradition in the cathedrals, a four-part tradition, with the principal melody sounding in the tenor voice (see example 6).30

Only later, after contact with continental custom during the Marian years, did English psalmody become an essentially unison practice. There is, however, an oral tradition, which may or may not be accurate, that suggests that the early metrical psalms were sung to popular melodies. It is known that tunes were specifically composed for them, and the evidence found in two Edwardian collections of metrical psalms31 suggests that tunes were also crafted out of the basic plainchant psalm tones.32 The two Anglican traditions of church music resemble one another: both employed four-part singing, both utilized the older traditional plainchant, and both depended on elements of continuity and discontinuity.

CONTEMPORARY IMPLICATIONS

Amid the great social changes of the sixteenth century and though different in detail, the musical responses of Lutheranism and Anglicanism blended creatively the continuity of the past with the discontinuity of the present. The music of the reforming movement, itself concerned with change within the sometimes violent mutations of the sixteenth century, was therefore neither reactionary nor rootless. Through the music from the past, contemporary Christians were given insight and encouragement to live in the present: through the music of the present, worshiping congregations saw that God was not only the God of yesterday but also the God of today. Continuity overstressed creates the danger of fossilization, an escapism that lives only in the past, willfully blind to the present. When discontinuity predominates, there is danger of disintegration, a different kind of escapism that lives only in the present, an existentialism that denies all traditional values. If either continuity or discontinuity displaces the other then disastrous social consequences follow, as later history demonstrates. In England the metrical psalm-singing puritans under Oliver Cromwell pursued discontinuity so tenaciously that they created a civil war. In Germany, earlier in our own century, Lutherans were so concerned with the authentic continuity of their fine tradition of church music from the past that they could not see where Hitler was leading them in the present.

In the reformation era in both Germany and England, continuity and discontinuity balanced in a creative tension. In late twentieth-century North America, we have been passing through a period of significant societal change that, in the process, has brought about a “restructuring of American religion,” as the research of sociologist Richard Wuthnow has perceptively demonstrated.33 As in the sixteenth century, there has been a concern to explore biblical theology and relate that exploration to contemporary society; to reach people outside ecclesiastical circles in order to share with them the insights of religious faith; and to find new, expressive, and inclusive ways of worshiping. Like the people of the sixteenth century, we too have been influenced by interrelated changes in the status of church musicians and in the emergence of a new technology.

Collaboration between minister and musician and the acknowledged dependence on each other’s expertise is changing dramatically. The theologian Luther knew it was necessary, when drawing up patterns of worship for Wittenberg, to call on the expertise of the gifted musician Johann Walter. Even Calvin, who was much more suspicious and restrictive than Luther about music in the liturgy, nevertheless knew the wisdom of working with such notable composers as Louis Bourgeois and Claude Goudimel in the provision of music for the Genevan psalter. Indeed, when the significantly expanded Genevan psalter of 1551 was being prepared for publication, Bourgeois also produced a small tract—presumably with Calvin’s encouragement—dealing with the basic rudiments of music that individuals in the congregation required for singing the metrical psalms.34 Today, congregations are led to believe that only music in a simplistic style is appropriate for worship and that professionally competent musicians are unnecessary. This extreme position deprives congregations of the breadth and depth that professional musicians can offer as partners with the clergy and the people.

Like the receivers of the new technology of printing in the sixteenth century, we, at the end of the twentieth century, also have new technologies of communication. Television is more pervasive than the sixteenth-century pulpit; and computer communication, more immediate than the sixteenth-century broadsheet. The growth of these electronic technologies in our society also brings with it the desire to control the flow of information. Various forms of censorship, or “rights of access,” now operate in ways that endanger our freedom by undermining the First Amendment.35 A similar censorship also operates with regard to the sacred music transmitted through the electronic media. The facile medium of television has produced its “lowest-common-denominator” approach in the worst excesses of televangelism,36 in which only one type of music is heard, one that reflects the materialistic desires of our society rather than the deeper spiritual concerns of our faith. Similarly, the advent of electronic publishing in connection with sacred music is likely to promote only a narrow range of anodyne and “popular” music, unless other publishers rise to the challenge of the medium.37

We appear to be in a period of transition, unsure where the future may take us. Despite positive possibilities,38 the signs favor discontinuity at the expense of continuity. As Eric Werner has pointed out,39 the synagogue of the Diaspora has been completely thrown off balance by the Holocaust, being dominated by survivalist policies; and the Catholic church, since Vatican II, has in large measure given up much of its musico-liturgical tradition.40 Many Protestant churches are little different in their preference for the “instant” music of contemporary commercialism and for the dismissal of the church music of continuity as either “churchy” or “elitist.” But we need the music of the past as well as the music of the present, as the German and English reformers discovered in the sixteenth century. They developed a sacred bridge linking continuity at one end with discontinuity at the other, a sacred bridge that must be kept accessible and serviceable for present as well as future generations of worshipers.

NOTES

1. See, for example, Robin A. Leaver, Luther and Justification (St. Louis, 1975), especially p. 13 and following.

2. See especially Gert Haendler, Luther on Ministerial Office and Congregational Function, trans. Ruth C. Gritsch, ed. Eric W. Gritsch (Philadelphia, 1981).

3. For older literature, see, for example, Ernst Tröltsch, “Renaissance and Reformation,” Gesammelte Schriften 4 (Tübingen, 1925), pp. 261–96; Patrick C. Gordon Walker, “Capitalism and the Reformation,” Economic Review 8 (1937): 1–19; Hajo Holborn, “The Social Basis of the Reformation,” Church History 5 (1936): 330–39. All three articles can be found, with some abbreviation, in L. W. Spitz, ed., The Reformation: Material Or Spiritual? (Boston, 1962). For more recent discussions, see the Harold J. Grimm Festschrift, Lawrence P. Buck and Jonathan W. Zophy, eds., The Social History of the Reformation (Columbus, 1972); the bibliographic essay by Thomas A. Brady, Jr., “Social History,” in Steven Ozment, ed., Reformation Europe: A Guide to Research (St. Louis, 1982), pp. 161–81; and Kyle C. Sessions and Phillip N. Bebb, eds., Pietas et Societas: New Trends in Reformation Social History. Essays in Memory of Harold J. Grimm, Sixteenth-Century Essays and Studies 4 (Kirksville, Mo., 1985).

4. For such an interpretation, see Eva Priester, Kurze Geschichte Österreichs (Vienna, 1946), pp. 111–19, trans. in W. Stanford Ried, ed., The Reformation: Revival or Revolution? (New York, 1968), pp. 98–105.

5. See Walter Salmen, The Social Status of the Professional Musician from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century (New York, 1983); Frank L. Harrison, “The Social Position of Church Musicians in England, 1450–1550,” Report of the Eighth Congress of the International Musicological Society, vol. 1 (Kassel, 1961), pp. 346–56; John W. Barker, “Sociological Influences upon the Emergence of Lutheran Music,” Miscellanea Musicologica: Adelaide Studies in Musicology 4 (1969): 157–98.

6. See, for example, Walter E. Buszin, “Johann Walther: Composer, Pioneer, and Luther’s Musical Consultant,” The Musical Heritage of the Church 3 (1947): 78–110.

7. Sometime around 1576, the composer Thomas Whythorne, who had published a set of madrigals in 1571 and a few years later became the master of music to Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, wrote in his manuscript autobiography: “Now I will speak of the use of music in this time present. First, for the Church, ye do and shall see it so slenderly maintained in the cathedral churches and colleges and parish churches, that when the old store of musicians be worn out, the which were bred when the music of the church was maintained (which is like to be in short time), ye shall have few or none remaining, except it be a few singingmen and players on musical instruments” (The Autobiography of Thomas Whythorne: Modern Spelling Edition, ed. James M. Osborn [London, 1962], p. 204).

8. For an excellent survey and bibliography, see Steven Ozment, “Pamphlet Literature of the German Reformation,” in Ozment, ed., Reformation Europe, pp. 85–105.

9. See Luther’s Works, ed. Jaroslav J. Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann (St. Louis and Philadelphia, 1955– ), vol. 31, pp. 22–23.

10. See Kyle C. Sessions, “Song Pamphlets: Media Changeover in Sixteenth-Century Publicization,” in Print and Culture in the Renaissance: Essays on the Advent of Printing in Europe (Newark, 1986), pp. 110–19.

11. See Charles Garside, Zwingli and the Arts (New Haven, 1966), pp. 54–56.

12. Luther’s Works, vol. 53, p. 316.

13. See further, Carl Schalk, Luther on Music: Paradigms of Praise (St. Louis, 1988).

14. For a translation of the Formula Missae, see Luther’s Works, vol. 53, pp. 19–40.

15. See further, Robin A. Leaver, “Verba Testamenti versus Canon: The Radical Nature of Luther’s Liturgical Reform,” Churchman 97 (1983): 123–31; Robin A. Leaver, “The Whole Congregation Sings: The Sung Word in Reformation Liturgy,” in Drew Gateway 60 (1990–1991): 53–73.

16. Composite translations.

17. For a translation of the Deutsche Messe, see Luther’s Works, vol. 53, pp. 61–90.

18. Luther was clearly unaware of the interrelationships between Hebrew, Greek, and Latin chant.

19. Luther’s Works, vol. 53, p. 63.

20. For a summary of the Lutheran tradition that proceeded from Luther, see Robin A. Leaver, The Liturgy and Music: A Study of the Use of the Hymn in Two Liturgical Traditions, Grove Liturgical Study 6 (Bramcote, 1976), pp. 14–24.

21. Quoted in Peter le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549–1660 (Cambridge, 1978), p. 11; see also C. A. Miller, “Erasmus on Music,” The Musical Quarterly 52 (1966): 332–49.

22. [Miles Coverdale], Goostly Psalmes and Spiritual Songes (London, c. 1535).

23. Miles Coverdale, The order that the churche and congregation of Chryst in Denmark, and in many places, countries and cities of Germany doth use (c. 1543), reprint ed. in G. Pearson, ed., Writings and Translation of Myles Coverdale (Cambridge, 1844).

24. See further Jerome Friedman, The Most Ancient Testimony: Sixteenth-Century Christian-Hebraica in the Age of Renaissance Nostalgia (Athens, 1983), pp. 102–6.

25. Historical surveys of the two traditions can be found in Edmund H. Fellowes, English Cathedral Music, Jack A. Westrup, ed. (London, 1969); and Nicholas Temperley, The Music of the English Parish Church, 2 vols. (Cambridge, 1979). A recent study, Stanford E. Lehmberg, The Reformation of Cathedrals: Cathedrals in English Society, 1485–1603 (Princeton, 1988), investigates the role of cathedral establishments during the far-reaching political and theological changes of the English Reformation era; a social history, the work stresses particularly the liturgical and musical consequences of those changes (see especially chapters 4, 6, and 8).

26. See Huray, Music and the Reformation, pp. 172–226; Denis Stevens, Tudor Church Music (New York, 1973), pp. 86–112.

27. See Fellowes, English Cathedral Music, p. 24.

28. See the articles by John Aplin: “A Group of English Magnificats ‘Upon the Faburden’,” Soundings 7 (1978): 85–100; “The Survival of Plainsong in Anglican Music: Some Early Te Deum Settings,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 32 (1979): 247–75; “‘The Fourth Kind of Faburden’: The Identity of an English Four-Part Style,” Music and Letters 61 (1980): 245–65.

29. See The booke of Common praier noted 1550, Robin A. Leaver, ed., Courtenay Facsimile 3 (Appleford, 1980), especially the introduction; and Robin A. Leaver, The Work of John Marbeck, Courtenay Library of Reformation Classics 9 (Appleford, 1978).

30. See Robin A. Leaver, ‘Goostly Psalmes and Spiritual Songes’: English and Dutch Metrical Psalms from Coverdale to Utenhove 1535–1566 (Oxford, 1991).

31. Robert Crowley, The psalter of Dauid newely translated into Englysh metre (London, 1549); F. Seagar, Certayne psalmes select out of the Psalter of Dauid, and drawen into Englyshe Metre, wyth Notes to euery Psalme in iiij parts to Synge (London, 1553).

32. A number of the French Genevan psalm tunes were also crafted out of traditional plainsong; see Pierre Pidoux, Vom Ursprung der Genfer Psalmweisen (Zurich, 1986), pp. 14–17.

33. See especially, Robert Wuthnow, The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith since World War II (Princeton, 1988); and Robert Wuthnow, The Struggle for America’s Soul: Evangelicals, Liberals, and Secularism (Grand Rapids, 1989).

34. Louis Bourgeois, Droict Chemin de Musique (Geneva, 1550); see facsimile and English trans. by Bernard Rainbow, The Direct Road to Music (Kilkelly, Ireland, 1982).

35. See Ithiel de Sola Pool, Technologies of Freedom (Cambridge, Mass., 1983).

36. The issues are more complex and far-reaching than can be dealt with here; see, for example, the discussions of Wuthnow cited in note 33, above.

37. For example, with traditional methods of music publishing, the costs of producing some compositions are currently prohibitive, but the prospect of producing copies “on demand” from electronic databanks opens up new possibilities.

38. See, for example, Robin A. Leaver, ed., Church Music: The Future. Creative Leadership for the Year 2000 and Beyond. October 15–17, 1989, Westminster Choir College, Conference Papers (Princeton, 1990).

39. See the preface to Eric Werner, The Sacred Bridge: The Interdependence of Liturgy and Music in Synagogue and Church during the First Millenium, vol. 2 (New York, 1984), p. xi.

40. See, for example, Thomas Day, Why Catholics Can’t Sing: The Culture of Catholicism and the Triumph of Bad Taste (New York, 1990), a perceptive diagnosis that lacks a coherent prescription.