23

Achieving Milestones While Losing the War

The Bush administration and its civilian and military leaders in Iraq worked hard to understand the situation and make smart decisions. The narrative of progress reinforced a stubborn refusal to change.

The administration had plenty of data to support its narrative. Iraq was hitting all the major benchmarks. Politically, the elections were taking place. Iraqis drafted and voted approval for a new constitution; they established successive governments and enacted legislation. The Iraqi government achieved every benchmark outlined in UN Resolutions 1546 (2004) and 1723 (2006).1 Iraqi security forces were being trained, equipped, and fielded on time.2 Coalition special operations forces captured Saddam and killed AQI leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The Sunni Arab and Sadrist insurgencies were suffering tremendous casualties. Economically, international aid agencies awarded major developmental contracts to Iraqi firms, and the oil industry was beginning to recover.3 In short, the administration was meeting its standards for success in its political, military, and economic lines of effort. It broke down the requirements into parts and organized resources to achieve each one, a classic attempt to solve the complexity of post-Saddam Iraq with an assembly line.

The Bush administration measured progress by individual milestones and silos. By October 2004, for instance, they had differentiated the enemy in Iraq into three tiers: Sunni Arab rejectionists, former regime elements, and international terrorists.4 Sunni Arab rejectionists were those “who have not embraced the shift from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq to a democratically governed state,” while Saddamists and former regime elements “harbor dreams of establishing a Ba’athist dictatorship.”5 American officials estimated that the first two tiers had some 3,500 fighters and 12,000–20,000 supporters. Foreign terrorists totaled roughly 1,000.

Nonetheless, the intelligence community, even in late 2005, had a tough time understanding the nature of the enemy, its relationship to the population, and the implications for US strategy.6 The difference between Sunni Arab Rejectionists (deemed reconcilable) and Former Regime Elements (considered irreconcilable) was hard to determine. Moreover, these distinctions treated the insurgency as a collection of individuals rather than as groups with political constituencies that had goals and objectives.

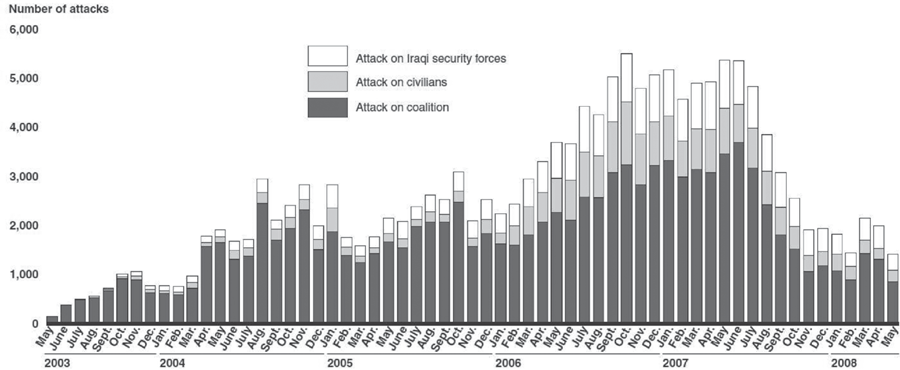

Figure 10. Annotated Enemy-Initiated Attacks, Iraq, 2003–2008

Source: US Department of Defense, Measuring Stability and Security in Iraq, Report to Congress, March 2008, 18 (events and trend lines added). For more on the challenges of assessing insurgencies, see Thomas C. Mayer, War without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1985). On analytical measures, see James G. Roche and Barry D. Watts, “Choosing Analytic Measures,” in Journal of Strategic Studies 14, no. 2 (1991): 165–209.

The Department of Defense graph in figure 10 charts enemy-initiated attacks (EIAs).7 These attacks were an imprecise but consistent indicator of insurgent strength levels. Weekly attacks increased roughly three-fold to 600 per week from January 2004 to July 2005. The upward trend continued to 800 per week when Maliki came to power in May 2006. Sectarian violence, as noted in the previous chapter, intensified. Curiously, the Bush administration did not include violence levels in the security assessment.8

Polling data revealed a more complicated picture. Surveys can be problematic in combat zones, especially if people believe they might be at risk of harm based on how they answer.9 Nonetheless, a significant percentage of Iraqis polled across ethnic and sectarian lines in March/April 2004 supported the idea of parliamentary democracy (54 percent), believed they would be better off five years from now (63 percent), and wanted laws guaranteeing freedom of speech (94 percent), assembly (77 percent), and religion (73 percent). Most surveyed believed US forces behaved badly (58 percent) and viewed them as occupiers (71 percent). The same poll showed widespread support for Iraqi police and the new Iraqi Army.10 A September 2004 poll conducted by the State Department, however, showed that Iraqi perceptions of security continued to decline.11 A significant percentage of Sunni Arabs (88 percent by January 2006) supported the insurgency or believed attacks on coalition and government forces were justified.12 “The Sunni Arab insurgency is gaining strength and increasing capacity,” a May 24, 2006, intelligence assessment surmised, “despite political progress and security forces development.”13

The interpretations of the data reveal the dominant mental model within the Bush administration and among US officials in Baghdad. Based on the progress in meeting political, military, and economic benchmarks, Vice President Cheney concluded on May 30, 2005, that the insurgency was “in its last throes.”14 CENTCOM commander General John Abizaid explained that the number of Iraqis in the rebellion was only 0.1 percent of the population.15 Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, even as late as August 2005, described the opposition as “dead-enders” and remnants of the former regime while downplaying the risk of civil war.16 The October 2005 Department of Defense report to Congress boasted, “One noteworthy strategic indicator of progress in the security environment is the continued inability of insurgents to derail the political process and timelines.”17 When questioned about the rising number of attacks, Rumsfeld explained that the military’s data collection was improving and “we’re categorizing more things as attacks.”18

The increasing violence remained an acute cause for concern, but accepted explanations for it conformed to the administration’s assumptions and way forward. Foreign occupation, the military command assessed, was a core motivator of violence. American officials believed that most Sunni Arabs supported the government but were prevented from showing it due to coercion and intimidation.19 General Abizaid explained that coalition troops generated “anti-bodies” within Iraqi society that were determined to throw out the foreigners.20 Once foreign forces withdrew, the insurgency would die out.

Notably, the administration resisted describing the armed resistance as an insurgency. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who had been using the term, decided in November 2005 to reject “insurgency” as an accurate description of those fighting the coalition and Iraqi government. “I think that you can have a legitimate insurgency in a country that has popular support and has a cohesiveness and has a legitimate gripe,” he noted. “These people don’t have a legitimate gripe.” He preferred the label “Enemies of the legitimate Iraqi government.”21 Embedded in this odd terminology dispute is Rumsfeld’s belief that Sunni Arabs had no legitimate reasons for fighting.

The US government’s tendency to divide the war into parts within bureaucratic silos reinforced the tendencies toward confirmation bias. Assessments simply added up tangible achievements within each department and agency silo rather than viewing the situation as a whole. Lieutenant General James Dubik offered an illustrative example of this mentality occurring as late as 2007. One of his general officers told Dubik that he had trained the requisite numbers of Iraqi soldiers, “so his task was complete,” and he was ready to go home.22

In short, officials in Washington, D.C., and Iraq assumed all the individualized progress was adding up to a successful outcome—reinforcing a belief that the war was on track. Confirmation bias masked how Iraqi elites were manipulating coalition efforts in those silos and how the silos began to self-synchronize in damaging ways.

The administration convinced itself that Iraqi public support would increase as the government achieved its political, military, and economic milestones, and thus reduce the insurgency.23 General Casey, for example, viewed the January 2005 election as a success despite the Sunni Arab boycott. The inability of al Qaeda to block the vote, as he saw it, was an indicator that the insurgency had little popular support.24 The focus on progress made along the political, economic, and security benchmarks would continue to dominate the quarterly reports submitted by the Department of Defense through August 2006.25 The Bush administration interpreted the relevant data and concluded that the war was on track. In this view, the best course of action was to follow the Casey operational plan and begin to hand over security to fledgling Iraqi forces.

Our theories, Albert Einstein reportedly observed, are what we measure. They also inform how officials make sense of the mountains of data bombarding them in a dynamic, interconnected world. Smart and experienced US officials interpreted these data points—including the massive increases in violence—as evidence that the war was on track. Alternatively, the data could suggest that Sunni Arabs were fighting against the new Shi’a-dominated order as well as foreign forces. If this latter interpretation were accurate, the civil war would continue even if American troops departed, but this was not the view within the Bush administration. Their stubborn insistence that the strategy was working prompted Senator Chuck Hagel to conclude, “The White House is completely disconnected from reality.”26

The American political left’s relentless calls for immediate disengagement—an approach which would have probably led to defeat—may have unwittingly reinforced the administration’s views. Bush resisted these calls, countering that withdrawal should be “conditions-based” along the standards outlined in the strategy.27 As will be discussed later, Rumsfeld and Casey dug in their heels until the very end against a proposed troop increase and change in the plan because they did not see the situation or their strategy as failing.