30

New Administration, Similar Challenges

The Obama administration embarked quickly on a strategy review for Iraq, determined to wind down the war and refocus attention on Afghanistan.1 When the administration settled on a new policy, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton issued guidance to the embassy in Baghdad in an April 8, 2009, cable entitled “U.S. Policy on Political Engagement in Iraq.”2 It outlined six “critical” objectives: successful national elections; avoid violent Kurd-Arab confrontation; develop non-sectarian, politically neutral, and more capable security forces; avoid Sunni-GOI (Government of Iraq) breakdown; prevent government paralysis; maintain macroeconomic stability. After noting some less critical objectives, the cable articulated a “new way forward” based on a “grand process(es)” policy that “focuses on setting in motion and energizing productive processes, but not necessarily resolution, on the full range of critical and significant challenges.” The United States “Will offer to play the role of honest broker and/or third-party guarantor of the Iraqi and U.N. reconciliation processes.” This engagement would address five issues, focused primarily on the Kurdish-Arab frictions. It would support the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) efforts to address disputed internal boundaries, support an election law specific to Kirkuk, promote the passage of a hydrocarbon law, and sustain an MNF-I coordinating committee with ISF and Peshmerga leaders. The fifth issue was Sunni Arab accommodation.

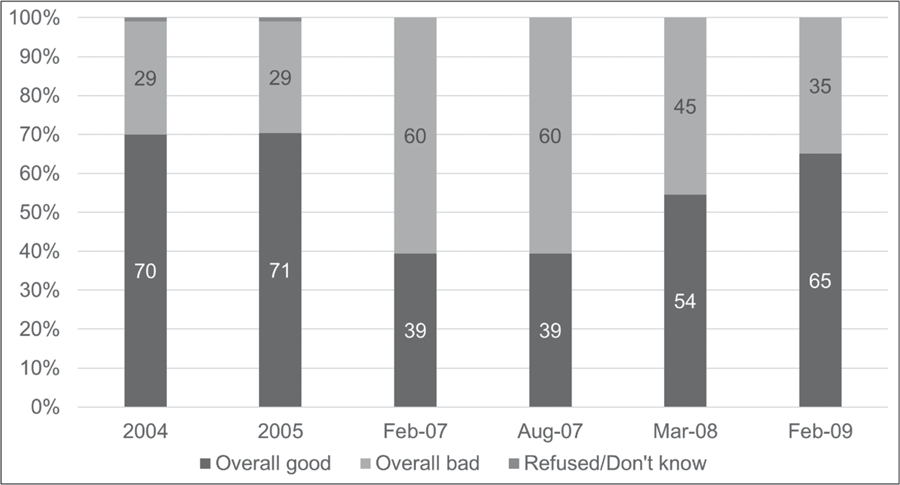

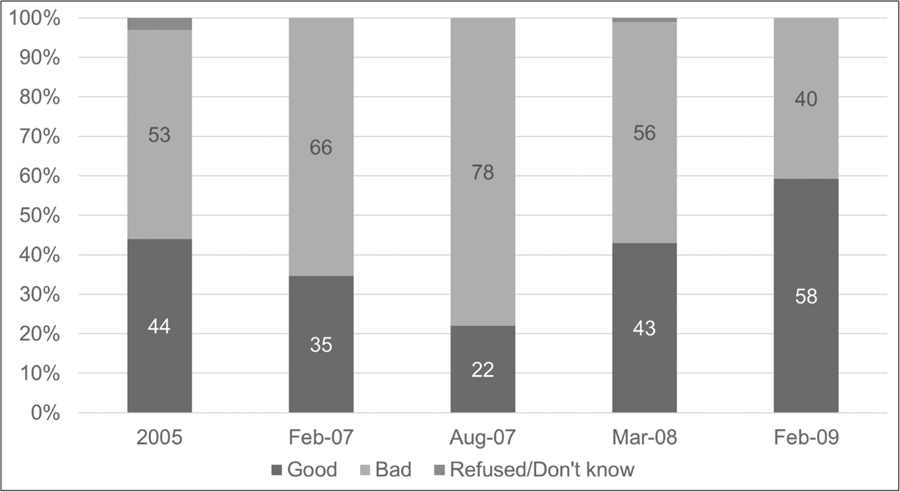

A February 2009 survey of the Iraqi population suggested a slightly more optimistic mood that could have been built upon to support the transition. Compared to pre-surge days, both Sunni and Shi’a were more satisfied with their lives (see figure 11) and with how things were going in Iraq (see figure 12). When asked about their satisfaction with specific areas, people attested an improvement across sectors, including security, their freedoms, and their economic situation.3 At the same time, confidence in the government and the Iraqi Army was rising, while trust in local militia had decreased since 2007. Support for a unified Iraq and a democratic political system was also as high as ever.

Figure 11. Iraqis’ Satisfaction with Their Lives

Question: “Overall, how would you say things are going in your life these days? Would you say things are very good, quite good, quite bad, or very bad?”

Source: Based on data in D3 Systems and KA Research Ltd., “Iraq Poll February 2009,” 1.

Assuming these figures were representative, this would have presented an opportunity for the United States (and a willing and able Iraqi government) to enhance political performance and inclusion in Iraq. However, bureaucratic and patron-client frictions complicated matters.

Due in part to the administration’s shift in strategic priority to Afghanistan, Clinton’s cable offered no resources or new authorities. “To carry out this policy, the Embassy and MNF-I are encouraged to reconfigure resources to support the five major processes (listed below) and to formalize an Embassy/MNF-I/UNAMI Working Group (including other parties as necessary) to coordinate these efforts.” The embassy in Iraq was to advance US objectives through meetings, working groups, and support to UNAMI. With no authority over the military mission, the embassy could not direct MNF-I efforts or resources; the latter was free to implement US policy guidance as it saw fit. The cable did not direct the embassy to devise an implementation strategy or outline ways to use existing US leverage to advance its objectives. The guidance cable stated its desire not to limit or constrain the mission. “Indeed, creative and responsible initiatives from the field that effectively advance the stated policy are encouraged when appropriately proposed and approved.” In other words, the embassy had no latitude. Ambassador Hill found that the easiest way to advance Iraqi agreement on the nonmilitary aspects of the policy was to pressure the Kurds and Sunni Arabs to accommodate Maliki’s demands, rather than the reverse.4

Figure 12. Iraqis’ Satisfaction with Their Country

Question: “Now thinking about how things are going, not for you personally, but for Iraq as a whole, how would you say things are going in our country overall these days?”

Source: Based on data in D3 Systems and KA Research Ltd., “Iraq Poll February 2009,” 3.

The most likely explanation for the emphasis on the Arab-Kurd frictions was its recent intensity coupled with the belief that enough Sunni Arab reconciliation was occurring to lower the risk of instability.5 The cable mentions areas of potential backsliding on the part of the Iraqi government on reconciliation, but orients on managing Sunni reactions: “Sunni political leadership is deeply fractured, rendering them more likely to advocate unhelpful, extreme stances, particularly during an election year. If mistrust grows, it could push Sunni Arabs out of the Iraqi national government and push more hardline Sunni Arabs towards a resumption of violence.” There was no mention in the cable of exploring ways that the United States might capitalize on the elections or apply other leverage on the Iraqi government to advance reconciliation.6

There was also no suggestion of any future SOFA negotiations. The Departments of State and Defense, as well as the intelligence community, presumably provided inputs that were concurrent with the new policy. The guidance sent by the secretary of state to the US embassy reflected the administration’s policy decision—the same decision upon which the secretary of defense would issue guidance to US Central Command and MNF-I.

Despite Hill’s upbeat view of Maliki and the administration’s decreased attention to Sunni Arab reconciliation, the Iraqi prime minister continued to weaken Sunni leadership.7 With al Qaeda in Iraq decimated, violence declining, and US forces leaving the cities, Maliki had a freer hand to reduce the power of the 100,000-member Sons of Iraq (SoI).8 He began to slowly dismantle the Sunni volunteers, after some initial efforts at US insistence to support them. In the fall of 2008, following pressure from Odierno, Maliki agreed to continue paying the salaries of 60,000 members and incorporate 40,000 into the ISF. The first tranche of volunteers went onto the government payrolls in October without incident.9 When a budget dispute erupted, Maliki took money from the Ministry of Interior budget to pay the SoI groups. In March 2009, however, he started arresting Awakening leaders.10 One such leader predicted to a US official that the government would “arrest all of us, one by one.”11 Then the Iraqi government stopped or substantially delayed paying member salaries. An Awakening member who wanted a job in the ISF had to navigate volumes of red tape, even for menial janitorial or servant positions. Sunnis in the mixed-sectarian Diyala province, east of Baghdad, were targeted disproportionately for alleged terrorist activities.12

Meanwhile, al Qaeda in Iraq was morphing into an underground organization, later to become the so-called Islamic State. “A few embers of Zarqawi’s Islamic state remained, kept alive by flickering Sunni rage,” writes David Ignatius. “The flame was nurtured at U.S.-organized Iraqi prisons such as Camp Bucca, where religious Sunni detainees mingled with former members of Saddam’s Ba’ath Party, and the nucleus of a reborn movement took shape.”13 The Islamic State was also aiming at Awakening leaders. Former army officer and battalion commander in Iraq Craig Whiteside, now a professor at the Naval Post Graduate School, counts 1,345 Awakening members killed by the Islamic State between 2009 and 2013.14 “Was anyone watching in Washington? Evidently not,” Ignatius argues. “Officials in Baghdad, meanwhile, didn’t seem to care; Maliki’s government was probably as happy to see the killing of potentially powerful Sunnis as was ISIS.”15

In Baghdad, Hill orchestrated Maliki’s visit to Washington in July 2009. If political reform was essential, it should have featured prominently in the churn of cables and talking points that go into scripting head of state visits.16 Maliki wanted to launch the Strategic Framework Agreement.17 Hill suggested in his cable to Washington that the administration advance the economic discussion, help facilitate a resolution to decades-long frictions with neighboring Kuwait, and encourage Maliki to visit Arlington National Cemetery to honor American sacrifices in Iraq.

The cable was silent on reform and reconciliation, painting Maliki as a post-sectarian leader.18 In the event, Maliki pressed the Iranian threat. If the United States could not get Sunni Arab states to stop fomenting unrest among Iraq’s Sunnis, he reportedly cautioned, Iran was likely to intervene more aggressively in Iraqi politics. He also protested that representatives of the coalition military met with exiled Ba’athists in Turkey.19 Political reform seemed to be absent from the discussions.

The next opportunity arose during the 2010 parliamentary elections. In the lead-up to the polls, Maliki aimed to outmaneuver his potential opponents.20 By securing a withdrawal timeline, he showed his ability to advance Iraqi sovereignty and demonstrate political independence from the Americans.21 He worked to marginalize Sadrists and other rival Shi’a parties while using his security forces to keep Sunnis off balance and in political disarray.22 He also aimed to undermine their campaigns. Shi’a candidates sometimes deployed graphic anti-Ba’athist themes in efforts to increase Shi’a turnout.23 Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi, a Sunni, meanwhile, threatened to veto the election law in hopes of gaining Sunni Arab seats from the Kurds. President Obama intervened successfully to pressure Kurdish president Massoud Barzani to accept the bill.24 Despite the fractious political maneuvering, all seemed on track, as the US embassy expressed confidence in the Iraqi High Election Commission (IHEC).25 That confidence shattered in January 2010 when the Accountability and Justice Commission (formerly the de-Ba’athification commission) barred roughly 500 candidates for parliament, mostly Sunni, over alleged Ba’athist ties.26 Hill noted the subdued reaction of some Sunni communities to the ruling, and even suggested it may be the “first tangible example of cross-sectarian cooperation.”27

Odierno reportedly took a dimmer view and raised a red flag to Washington. Hill was instructed by the Obama administration to address the issue with Maliki.28 The prime minister was intransigent.29 Obama next sent his point man on Iraq, Vice President Joe Biden, to Baghdad. According to an embassy reporting cable cleared by Biden’s office, the vice president noted two concerns to UN Special Representative for Iraq Ad Melkert. “[T]hat the government had a serious responsibility to continue service delivery during the [post-election] transition, and that it was critical not to waste time during the period of government formation.”30 Advancing political reconciliation was absent from the list, and, according to a reporting cable, Biden did not raise the issue with Maliki. The prime minister assured Biden that he was not paranoid about Ba’athists but viewed them as a “malignant virus.” Biden praised Maliki for democratic progress and political consensus, assuring US support while Iraq handled the de-Ba’athifcation issue according to its laws.31 While the Americans were able to get many barred candidates reinstated, the bans had a disruptive effect. Maliki believed his State of Law list of candidates would win handily.32

The US country team was not so sure. Opinion polls suggested a tight race with Ayad Allawi’s Iraqiya Party—a cross-sectarian Shi’a-Sunni coalition.33 Maliki, however, had tools in place to shape the outcome and stacked the intelligence and security services with loyalists.34 The Accountability and Justice Commission could disqualify winning candidates. Maliki controlled the judiciary and had the executive powers to declare a state of emergency. The US country team consulted with the White House, where, according to Gordon and Trainor’s interviews with participants, Odierno pushed for guidance if this scenario came about. “We need a Maliki strategy,” Hill reportedly said, “he is the only one with the tools to screw up democracy.”35 This admission by the US ambassador was stunning. If anyone should have developed and briefed a “Maliki strategy,” it should have been Hill. Instead, he pushed the matter to Washington officials, who were in no position to create it from scratch. Unsurprisingly, the United States punted.36 They were in the final stages of a contentious strategy review for Afghanistan, a higher priority for them than Iraq.

The elections provided yet another golden opportunity to exercise leverage. If the results were to be as close as the polls suggested, a disputed outcome would be likely. According to Iraq’s election law, the party that wins the largest bloc of seats gets the first opportunity to form a government.37 American support, one way or another, could tip the balance. Allawi’s cross-sectarian coalition was more likely to promote political inclusion. Still, it would need US support in preventing Maliki from using extra-legal or even violent means to stay in power. Hill reportedly believed that Maliki would emerge from the election as the prime minister, whether legally or not.38 Either way, the United States had a chance to advance political reconciliation.

The results on March 7 were as Odierno guessed. Allawi’s secular Iraqiya list won 91 seats to Maliki’s State of Law coalition’s 89 and narrowly won the popular vote.39 Iraqi National Alliance (INA), the competing Sadrist Shi’a bloc, took 70 seats. INA and State of Law had split because the former did not intend to endorse Maliki for another term. The Kurdish bloc won 57 seats. Maliki was incensed and moved forward aggressively to challenge the results.40 He alleged that his opponents had cheated, and that the UN was complicit, so he reportedly sent a letter to the Americans demanding a recount in Baghdad and potentially in Mosul and Kirkuk.41 He also aimed to use de-Ba’athification. The Accountability and Justice Commission conducted another review of candidates for alleged Ba’athist ties. Maliki asked for a ruling on the “largest bloc” language in Article 76 of the constitution. The pro-Maliki judiciary said the largest bloc could mean the party that won the most seats or a bloc assembled in parliament after the election.42 These efforts gave Maliki the time and the opportunity he needed. If Maliki could gain INA support, he could claim the largest bloc.

Gordon and Trainor report that Odierno argued for the United States to get involved. He supported the Iraqiya case. Hill appeared to be less concerned about a Maliki victory and believed that the Saudis bankrolled Iraqiya and other Sunni parties.43 With no in-country political strategy in place and the ambassador and commander in disagreement, the NSC had to handle the issue. While Washington considered the contrasting views from the field and deliberated whether and to what extent to get involved, Hill urged Iraq’s politicians to start forming a government.44

Iran moved more quickly. They invited Iraq’s Shi’a politicians to Tehran for Nowruz celebrations and urged them to come together. Although that was not yet agreed, the Shi’a parties on March 22 did support Talabani, who was also in attendance, to remain president.45 By early May, Iran had convinced the State of Law and INA parties to merge into a single coalition: the National Alliance, with Maliki as the head. Together, they tallied 159 seats, just four fewer than the 163 needed to form a government. Iraqiya sought international support for its right to try to form a government, but nothing of substance was forthcoming.

Meanwhile, on April 26, a special judicial panel upheld a decision by the Accountability and Justice Commission to disqualify 52 candidates, one of whom was Iraqiya. Even if Allawi had the opportunity to form a government, he was highly unlikely to amass a majority. With the Shi’a mega-coalition created and the election outcome safely in Maliki’s hands, an Iraqi appeals court overturned the earlier de-Ba’athification disqualifications, which removed an obstacle to certifying the election results.46 The Obama administration rationalized that Allawi would have been unlikely to win enough support to form a government anyway, but Iraqiya never got the opportunity to try. Sunnis saw American acquiescence as a betrayal of the democratic process.47 Maliki still needed the support of the Kurds to secure the 163-seat majority, and Barzani pushed hard to extract the best price for his help.48

At this point, the US team in Baghdad rotated. General Lloyd Austin replaced Odierno, and James Jeffrey (who had served previously in Iraq) took Hill’s place as ambassador.49 The Obama administration tried to bandage the election dispute by supporting a power-sharing arrangement among the rivals. James Steinberg, the deputy secretary of state, reportedly objected to the decision, because he believed it was more likely to produce gridlock and antagonism.50 The administration persisted in the approach through the summer and into the fall of 2010. Maliki would remain as prime minister, but Allawi would head a newly created Strategic Policies Council. Allawi saw the powerlessness in the manufactured position and rejected it. The Americans then sought to promote Allawi as the president, which would mean Talabani would need to step down. That was a political blow to the Kurds and Talabani himself, but also a problem for his rival Barzani, who did not want him back in Kurdistan.51 Various US officials attempted to persuade Talabani to give up the presidency. He refused.

On November 4, the administration took the extraordinary step of arranging a phone call between Obama and Talabani. The former pressed his fellow sitting president to step down. Talabani refused. The Kurdish leaders felt taken for granted.52 By November 10, with Iran brokering an agreement between Maliki and the Kurds, Allawi likely recognized that the Strategic Policies Council was the best he would get. He reluctantly accepted, but the arrangement collapsed immediately. Allawi never joined the government. Most of Maliki’s promises to the Kurds never materialized.53

Gates argues that the absence of sectarian violence between rival parties was a “mark of significant progress.”54 Such an indicator is misleading. Both leading candidates were Shi’a, so sectarian violence between them was unlikely. Maliki could manipulate the law to tilt the scales in his favor. Allawi would need American support if he hoped to form a government. Political violence by his party would have undermined any hopes of securing US backing. By focusing on putting the election crisis in the rearview mirror, the administration got nothing for the effort in terms of advancing reform and reconciliation.55 Their efforts resulted in greater Sunni Arab and Kurdish resentment. Over the next 18 months, Maliki moved aggressively to crush Sunni leadership.56

A final opportunity for the United States to exercise its waning influence for reform and reconciliation came in 2011 as the administration attempted to renew the 2008 Status of Forces Agreement.57 The United States had agreed in 2008 for all troops to leave the country by December 31, 2011—an outcome both Maliki and most Iraqis wanted. They were not alone. With the Americans out of the country and the governing coalition overwhelmingly Shi’a, the biggest winner was Iran. The Obama administration’s enthusiasm for maintaining troops there was low. He had campaigned on a promise to get out of Iraq, and now his new country team was pushing to maintain a substantial presence. The Arab Spring was convulsing the Middle East and, along with Afghanistan, occupying the attention of the administration.58

As has been discussed in Part IV, Obama had dramatically escalated the war in Afghanistan, but the Taliban appeared no closer to collapse or to entering a peace process. The Karzai government was rife with corruption. Tensions between the two presidents were high. The US troop surge there was to begin receding in July 2011. Obama and his inner circle may have been sensitive to criticism about ignoring the advice of his commanders on the ground. They had accused the military of trying to “box in” the president regarding the troop surge in Afghanistan. They then fired General Stanley McChrystal after disparaging remarks by his staff were reported in Rolling Stone.59 With the 2012 US elections just around the corner, another crisis with the military could be unhelpful. In short, both Maliki and Obama had incentives to let the SOFA expire while avoiding blame for doing so. The concessions needed to secure an agreement would need to be high enough for both to justify the political risk.60

Gordon and Trainor report that General Austin offered his estimate for the post-2011 force to cover the training, advising, and counterterrorism missions: 20,000 to 24,000 troops, which he assessed would still entail moderate risk. The Pentagon asked Austin to review the numbers again, which the latter revised downward with a preferred option of 19,000 troops, a middle option at 16,000, and a low choice of 10,000, which he deemed high risk.61 The Pentagon must have massaged the numbers a bit more because an April 29, 2011, Principals Committee discussed options at 16,000, 10,000, and 8,000 troops.62 Secretary of Defense Gates thought the lower two options could work.63 Admiral Michael Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, however, supported Austin’s recommendation of 16,000. Both flag officers reportedly believed that having no troops at all in Iraq was better than having too few. Mullen exercised his legal right as chairman and the president’s principal uniformed military advisor to express his concerns in a written memo to the national security advisor, Tom Donilon.64 The arguments, however, remained fixated on troop numbers, without mention of political reform and reconciliation.65

In May 2011, Maliki hinted that he might support an American military presence if he could garner enough political support.66 Obama, fresh off the successful Abbottabad raid that killed Osama bin Laden in his villa in Pakistan, approved a residual force in Iraq of up to 10,000 troops.67 By early June, the Obama administration communicated four conditions that the Iraqis would have to meet for US forces to remain. First, the government of Iraq needed to make an official request. Second, Maliki would need to gain parliamentary approval for a SOFA continuing the same 2008 legal immunities for US soldiers in Iraq. Third, Maliki would need to fill the vacant Ministry of Defense position and other open positions within the security ministries. Finally, Maliki had to act against Iran-supported militants, which had been using EFPs (explosive force penetrators) and IRAMs (rocket-assisted mortars) against US troops.68 Whether intended or not, the second requirement was a poison pill. The United States appeared to be dictating internal Iraqi government procedures. Even if Maliki wanted US troops to remain, the concessions he would likely have to make to gain approval would have been substantial—especially considering Iraqi public opinion on the matter.69 Two former senior White House officials with knowledge of both the 2008 and 2011 negotiations note that Maliki got what he wanted in 2008; he would be highly unlikely to overturn the timeline without major US concessions.70

Nonetheless, this provision gave both Obama and Maliki a reasonable escape from potential blame.71 In August, Obama further reduced the maximum presence to 5,000.72 The political risk of meeting the conditions for so little gain was likely deemed by Maliki to be too high. In the event, Iraqi leaders supported US military trainers but ruled out immunities. Obama ended the negotiations on October 21.73 A former senior White House official told New York Times correspondent Peter Baker, “We really didn’t want to be there, and he really didn’t want us there. . . . It was almost a mutual decision, not said directly to each other, but, in reality, that’s what it became. And you had a president who was going to be running for re-election, and getting out of Iraq was going to be a big statement.”74

As the US forces prepared to leave, Maliki’s sectarianism was in full swing. Provinces with significant Sunni populations such as Diyala, Salah ad-Din, Ninewa, and Anbar began to demand autonomy under a provision in the Iraqi constitution.75 Shi’as stormed the provincial council building in Baqubah (Diyala).76 In a joint press conference on December 12, just weeks before the last US troops were to leave Iraq, Obama praised Maliki’s efforts in leading Iraq’s “most inclusive government yet.”77 Deputy Prime Minister Saleh al-Mutlaq told CNN he was shocked that Obama greeted Maliki as the “elected leader of a sovereign, self-reliant and democratic Iraq” in light of his continued aggressive targeting of Sunni Arab leaders.78 Maliki reportedly told Obama that Iraq’s Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi and other Sunnis in his government supported terrorism.79 One week after being lauded by Obama for inclusiveness, Maliki sent troops to arrest Hashimi. The latter fled in time, but 13 of his bodyguards were tortured and sentenced to death.80

By mid-2014, less than three years later, a new Sunni Arab insurgency was flourishing.81 Daesh, the so-called Islamic State, had taken Ramadi, Fallujah, Mosul, and Tikrit and established a proto-state along the Euphrates in Iraq and Syria by feeding on the alienation of Sunni Arabs and engaging in a sophisticated combination of coercion, selective violence, and local governance.82 In September 2014, US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper confessed, “We underestimated ISIL [the Islamic State] and overestimated the fighting capability of the Iraqi Army. . . . I didn’t see the collapse of the Iraqi security force in the north coming. . . . It boils down to predicting the will to fight, which is an imponderable.”83 That might be true, but the misjudgment was more significant. Winding down the Iraq War was a higher priority than taking the steps needed to bring about a favorable and durable outcome, which may have motivated US policymakers to rationalize the myriad signs of trouble that pointed to a potentially explosive political fragility. “U.S. policymakers and planners did not pro-actively consider the transformative nature of the withdrawal of U.S. military forces,” argues a RAND study, “and the effects that transformation would have on strategic- and policy-level issues for both Iraq and the region.”84