Map One. The province of Ontario in relationship to Canada and the United States.

Only two American states, Indiana and California, received more Carnegie grants, 164 and 142 respectively, than the province of Ontario. Of the 111 buildings originally constructed with Carnegie support in Ontario, seventy-nine continue to be used as libraries although few—most notably the New Liskeard Library—do so without some renovation. Maps 1-4 shows the location of the original and remaining libraries, while Tables 12-14 list them.

Unfortunately, fifteen of the buildings as shown in Table 13 were demolished to make way for new construction, or were destroyed by fire.

Another seventeen buildings no longer serve as libraries, as per Table 14, but have been converted for other uses, most frequently still serving a civic function such as the Department of Engineering in St. Thomas, or the Police Department in Waterloo.

Amherstburg

Ayr

Barrie

Beaverton

Bracebridge

Brantford

Brockville

Brussels

Campbellford

Clinton

Dresden

Durham

Elmira

Elora

Essex

Exeter

Fergus

Forest

Fort Francis

Fort William

(Thunder Bay)

Glencoe

Goderich

Grand Valley

Gravenhurst

Grimsby

Hanover

Harriston

Hespler

Ingersol

Kemptville

Kenora

Kincardine

Kingsville

Lindsay

Listowel

Lucknow

Markdale

Merritton

Milverton

Mitchell

Mount Forest

New Hamburg

New Liskeard

Norwich

Norwood

Orangeville

Orillia

Ottawa West

Branch

Owen Sound

Palmerston

Paris

Parkhill

Pembroke

Penetanguishene

Picton

Port Elgin

Port Hope

Renfrew

St. Marys

Seaforth

Shelburne

Smiths Falls

Stirling

Stratford

Tavistock

Teeswater

Thorold

Toronto—

Yorkville

Riverdale

Wychwood

High Park

Beaches

Annette

Walkerton

Wallaceburg

Watford

Welland

Weston

Woodstock

Chatham

Collingwood

Cornwall

Guelph

Kitchener (Berlin)

Leamington

Mimico (Etobicoke)

North Bay

Oshawa

Ottawa (Main)

Sarnia

Sault Ste. Marie

St. Catharines

Tillsonburg

Windsor

Aylmer

Brampton

Dundas

Galt

Hamilton

Midland

Niagara Falls

Perth

Peterborough

Preston

Simcoe

St. Thomas

Stouffville

Toronto Reference Library

Toronto:

Queen and Lisgar Branch

Waterloo

Whitby

Map One. The province of Ontario in relationship to Canada and the United States.

Niagara Falls Carnegie library. One of the seventeen buildings no longer used as a library, the Niagara Falls Carnegie building is currently used by Community Services.

A record of the Carnegie libraries would be incomplete without some description of the collections and services that were available in Ontario in the first years of their operation. A few of the Library Boards or Town Councils preserved some record of their Carnegie Library activities in letters, either to Carnegie or Bertram. Andrew Braid wrote from Windsor a year after their new building opened in 1903, that:

I am as proud as a piper at our new building; and altho it has increased my library work (which has to be done in the evenings and after office hours), I am more than repaid at the knowledge that the number of readers and the circulation of books have increased greatly. We allow unrestricted access to the stack room, and it is a fine sight to see the number of people scattered among the shelves, selecting or examining the books. We find an improvement in our readers’ tastes—less fiction and more of the general works being taken now. From my heart I thank you for your gift to Windsor, and I am proud to have been the means of interesting you in the matter.2

The Hanover Town Council appointed a special Committee to thank Bertram officially, after their Library opened, and it reported on their library’s increased use as well:

The building itself and the purposes for which it was built is highly appreciated by the public, as the following figures will show. The average monthly visitors to the Reading Room since the building is in use is not less than fifteen hundred (1500), and the books charged each month amount to eight hundred (800). This represents a gain in the Reading Room of about 90%, and in the distribution of books of about 125%, which is most gratifying.2

Such letters in the Carnegie correspondence are few. Fortunately, the annual reports which had to be submitted to the Inspector of Public Libraries if a government grant were to be obtained provide a cross-section of library services in the early Carnegie libraries.

By 1906 some twenty Carnegie libraries had been completed, most with a stack room that could be kept closed to the general public, or to some category of it. Both large and small libraries denied such access to books, for example Ottawa, St. Catharines, Waterloo, St. Marys and Collingwood. Other libraries, such as Berlin, St. Thomas and Stratford, allowed free access except to the fiction collections, whereas others restricted access by age. Paris had an age limit of fourteen years, Waterloo’s was twelve, while St. Thomas regulations stated that: “Normally children under twelve are not permitted to take out books, but in reality the matter is left to the discretion of the librarian.”3 Windsor was even stricter and their age limit was sixteen, but the Librarian was given discretionary power. Berlin solved this problem by allowing parents to take out cards and books for their children. Many libraries, however, did give free access to all collections: Paris, Picton, Guelph, Chatham, Bracebridge and Harriston were examples of this more advanced thinking.

Card catalogues were fast becoming popular by 1906, and many libraries were switching from printed catalogues for part or all of their collection. Similarly, most libraries were either using or planning to use the Dewey Decimal classification, which had been developed in 1876 in the United States, and was being encouraged by the Inspector of Public Libraries for Ontario public libraries. St. Thomas reported in 1906 that: “Our librarian was this summer sent to Boston, Mass., to learn the Dewey System, and this system is now being introduced. We intend to have a printed catalogue for the books in fiction, and an indicator to show whether they are in or out. Books in fiction will be numbered according to the Cutter table. For books other than fiction we intend to use the Card Catalogue and the Dewey classification.”’4

Stratford had similar plans, but described their existing system as follows: “The shelf grouping is in 12 sections, biography, poetry and religion being classified by author, history and travel by country alphabetically, physics and science by sub-section under title. The Dewey system will replace the present system at an early date.”5

Children’s library services had been recognized in a very few of the early Carnegie libraries. Waterloo reported on a catalogue for children as did Berlin, while Guelph’s special effort was: “Two large tables provided with bound volumes of illustrated periodicals are placed in the general reading room for the use of children.”6 The Sarnia report described the most advanced service for children in any Ontario Carnegie Library to that date:

Special attention is devoted to library work for children.

Books suitable for children in every department of literature have been freely purchased. The assistant librarian has been given special charge of children’s work.

A story hour has been inaugurated by the children’s librarian.

Stories are told to the children so as to interest them in great men, or events, and in nature study, science, etc. The children are told what books are in the library dealing with the subject of the story, and encouraged to read for themselves.

The policy of the Board has not been to send out Travelling Libraries to the schools, but to bring the children to the library.

The Board has secured the co-operation of the teachers who make lists suitable for the different forms. Copies of these lists are given to the children’s librarian, and to the scholars in each form, and form part of the school curriculum.7

Emphasis placed on this special service to children resulted in rapid changes. In 1906 Ottawa reported that their Library contained a Children’s room with special books and that the Library “cooperated with local schools.” By 1909 this service had increased to a separate card catalogue and circulation system for the children, and in addition:

Special efforts are being made to co-operate with the schools. Collections of books are sent from the library to the Collegiate Institute and several of the larger public schools. Negotiations are also on foot with the Separate School Board looking toward a similar arrangement. It is hoped that in time a complete system of small libraries will be installed in the public, separate and high schools of Ottawa through the public library. The librarian has issued a special teacher’s card, entitling the holder to take ten books at a time and keep them for a month. This privilege applies to all teachers in Ottawa schools of every description, public and private, and also to the students in the Normal School.8

A variety of other special services were mentioned in the 1906 reports, including German books in Berlin and special meetings of the Historical Society in Lindsay. Sarnia described the most variation in their cultural activities:

The auditorium may be used by any body of a public or semi-public nature, without charge. The Historical Society, The Children’s Aid Society, The Medical Association, The Camera Club and other Societies regularly meet in this room.

The Smoking room is supplied with newspapers and tables for chess and checkers are provided.”9

St. Thomas also had an active programme: an auditorium seating 300 persons was used for meetings of an “educational character.” Typical of these was a lecture by “William Wilfrid Campbell, Canadian poet,” two weeks after the Library opened in February 1906.10

For many of the communities, the increased facilities and opportunities for more than the mere lending of a few books which the Carnegie libraries provided presented a major challenge. Regulations for library use, cataloguing and classification systems, monitoring of auditorium or lecture rooms, training for library staff, were all issues which had to be handled, many for the first time. Guidance provided by the Inspector of Public Libraries and by the Ontario Library Association encouraged communities to expand library services to match the handsome new Carnegie buildings. Financial support, however, remained a problem and resulted in great variations in the number of books or other services available. Table 15, which includes data from some of the earliest Carnegie libraries, illustrates some of these differences.

Library collections, as might be expected, were very small in the early years of the Ontario Carnegie libraries, with most libraries containing one book for each citizen—or fewer. Waterloo was the only community that approached modern standards of two or more books per capita. Use of the collections, as measured by circulation figures, is also interesting, in that the Guelph usage is so much higher than in other libraries. This might be explained by the fact that Guelph was the first free public library in Ontario under the 1882 Act,12 or by differing library regulations—fiction did not circulate in all libraries, for example.

Books could be purchased for as little as fifty cents each, and only a few hundred new books were added to most collections each year. Assistance was provided in the selection of appropriate titles through the Department of Education, which recommended that the American Library Association catalogue of 7,520 titles be used since it was considered to be “indispensable as a guide in selecting books.”13 The Ontario Library Association also provided book lists for both adults and children, “as an aid to the smaller libraries without trained librarians.”14 Public Library Inspector Leavitt was concerned about the development of the collections in the public libraries, noting that in 1906 the purchase of fiction consumed as much as 75 per cent of some libraries’ book budgets. He recommended that the Minister of Education be empowered to reduce that percentage to 45 per cent.15

Staffing was also a problem in the Carnegie libraries in their early years. Nursey reported in 1909 that he hoped to begin a summer school for library training in Toronto, similar to the one at McGill University, but this was not seen, evidently, as an urgent need.16 Library trustees assumed that they should be responsible for book selection, and that training for other library activities—purchasing, cataloguing, children’s services and promotion—while desirable, was not essential. Library staff appointments tended to be made, therefore, for reasons other than technical or professional qualifications: political favouritism, relationship to board members, and religious affiliations were all influential in staff choices. The attitude generally held about library staff qualifications was best expressed at a 1911 Library Institute meeting held at Niagara Falls:

It is very important to have a librarian with a high education but this is not all important. I would say it is more important to have a pleasant young lady as librarian, one who is enthusiastic in the literary work; also one who loves children. It is all the better if she has a good education, but in our small libraries we cannot always pay the price for education.17

To overcome these well-entrenched opinions, Inspector Nursey finally persuaded the Department of Education to fund a library training programme, and a five week summer course was begun in 1911 at the Toronto Model School, with one of Ontario’s first professional librarians, Mabel Dunham of the Berlin Public Library, as instructor.18 This course continued in the following summers, but failed to attract attendance from smaller urban and rural libraries as had been hoped.

Most of the original Carnegie libraries have been renovated in some manner, whether it is through the addition of carpeting and paint as in the Waterloo and Essex County libraries, or through extensions of the original buildings. These additions frequently have been done with some attention to the original design or function; those in Elmira, Owen Sound and Barrie for example, have not seriously compromised the Carnegie buildings. Others, such as Orillia and Wallaceburg, have buried the Carnegie facade within modern glass and brick designs.

It is unfortunate that some of the perceived problems of contemporary Carnegie libraries came from Bertram’s original concepts. Most serious was his insistence that the basement be designed so that it could be used for a lecture room, which resulted in extensive internal and/or external stairways leading to the main library floor. Access for senior citizens or handicapped persons is difficult if not impossible (for example, there are more than twenty steps from the sidewalk to the circulation desk at the Milverton Public Library). Moreover, the fixed wall shelving under high rear windows which Bertram favoured proved inadequate for growing collections within a few years, and an extension to the entire building was shown to be far more costly than expansion of a small stack room. At the same time it must be recognized that those libraries which followed Bertram’s original direction for few or moveable partitions have found it much easier to adjust functions to accommodate modern library services.

Refurbishing the libraries to meet present building standards with respect to heating, lighting and air conditioning or to support new technology has also proven difficult—and costly. The Goderich Carnegie Library has sufficient space for library functions but the cost for new heating and wiring, storm windows, insulation and carpeting required to bring the total building to an acceptable condition is currently considered too high. Meanwhile the second floor of the Library remains empty.

Problems of operating the two or three storey libraries should also be mentioned, since the total floor area cannot justify the larger staff numbers required if supervision must be provided for a library function— such as children’s services—on other than the main floor. Some of the smaller communities have solved this problem by retaining all library functions on the main floor, allowing the basement to be used for community services. In Dresden a ladies’ group gathers regularly for quilting, senior citizens meet in Orangeville, Lucknow shares its space with municipal offices, whereas Penetanguishene has the police department and Seaforth a day nursery in their library basements. Another problem of the three storey libraries is the inadequate structural strength of the second floor. Waterloo, for example, found that its top storey did not meet building code requirements for bookstacks.

The one floor libraries are particularly successful where a centralized book selection and processing service is provided through membership in provincial, county or regional library systems. The Carnegie Library can then be retained as a library public service centre, with collections continuously replenished from the central pool of books, films, or records, and with Telex, or in the future, computer terminals, linking it to its neighbours in an expanded library and information network. Essex, Lambton and Waterloo Counties have extremely good examples of this solution.

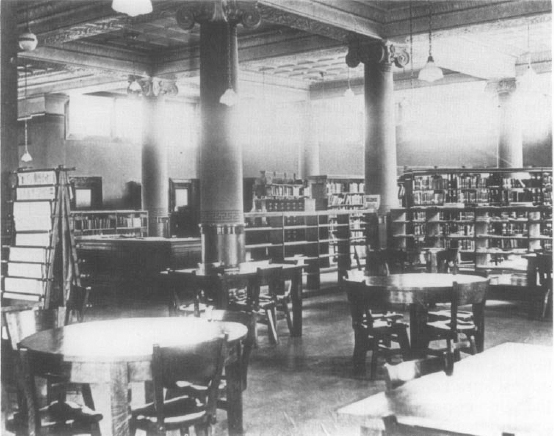

Mitchell Carnegie library. The high rear windows allowed wall shelving to be placed below, a feature much admired by Bertram.

Fort William Carnegie library. Now the Brodie Street Resource Library, Thunder Bay, this building has been successfully renovated, preserving the beauty of the original interior without compromising an efficient operation.

Galt Carnegie library. It was impossible to expand this building due to the constraints of the site, and it has been used for non-library purposes for many years.

Renovations or additions which reflect concern for operating costs and the needs of senior or disabled citizens, and yet maintain the integrity of the original Carnegie design are still possible. Toronto is a good example. With seven of their branches originating as Carnegie libraries (either for Toronto or the earlier community of Toronto Junction) the Toronto Library Board embarked on a renewal programme in 1976. Typical of these are the Yorkville and Annette Branches, both of which have renovations and additions which complement the original, distinctive architecture while meeting changing library service requirements.

The Fort William—now Thunder Bay—Carnegie Library has also been restored close to its original condition, with architect, interior design consultant and librarian working together to achieve excellent results in historical, operational and aesthetic terms. The St. Thomas Carnegie building, although no longer serving a library function, is another example of a careful renovation, entirely sympathetic to the earlier design and concepts. The work done in renovating or restoring the Carnegie libraries in the American state of Ohio should also be mentioned. A recent survey of the 105 Carnegie libraries in that state revealed that seventy-six were still in use as libraries and that in many communities these buildings served both as tourist attractions and points of reference. The feeling of “being home, the sense of permanence, the fond recollection of childhood reading” have directed many Ohio communities to hold their Carnegie libraries in a place of near veneration, either maintaining them as libraries or re-cycling them for some other public purpose.1

The City of Cleveland, like Toronto with many Carnegie buildings among its 33 branches, has had an award winning renovation completed by David L. Holzheimer, Koster and Associates, Architects. This Cleveland firm has overcome access problems in this and other Carnegie renovations through the use of small, open elevators, and relies on modern lighting techniques to emphasize the beauty of the original building design, whether Modified Renaissance, French Renaissance, or a copy of the British building for the St. Louis Exposition (in turn copied from Christopher Wren’s design for the Orangery at Kensington Palace).2

Other cities and towns in the United States are also recognizing the value of their Carnegie libraries. “Our Carnegie has been a focal point of civic pride through its life, and there is a strong community sentiment in favor of retaining the original character of the building,” reported Brian Davis of the Iowa Public Library, in response to questions from the American Library Association. Residents of Watertown, Wisconsin passed a referendum which favoured retention of their Carnegie library, renovated, over a newer, more modern facility, and Cedar Rapids, Iowa citizens defeated four referenda that would have caused the Library to move from the Carnegie building to a new library. Also in Iowa, fifty-three Carnegie libraries have been moved to the National Register of Historic Places.3

The American consensus that preservation of Carnegie libraries is desirable in most instances is not matched in the United Kingdom. Although a few libraries have published jubilee histories expressing tribute and warm appreciation to Carnegie, the high cost of renovation to make the older buildings acceptable for new library services has placed the majority in disfavour.”4

It is not difficult to understand why the Carnegie grants for library buildings were discontinued when one considers the frustration of those, particularly Bertram, dealing most intimately with them. The inability of many communities to complete their building within the granted amount, the ineptitude or unwillingness of architects to meet Bertram’s concepts of “effective accommodation,” the waste of money through increasing decoration, the broken pledges, the petty complaints and arguments— all have been documented. By the beginning of the first world war, therefore, the Carnegie Corporation was using questionnaires in the United States and the Inspector of Public Libraries in Ontario to determine the status of communities still requesting or already recipients of Carnegie benevolence. It was known by this time that at least some of the maintenance pledges were not being respected, and other abuses, such as the introduction of basement dance halls, were suspected of other communities.

In order to confirm their suspicions directly and to shape future policies about libraries and the grant programme, the Carnegie Corporation, in November, 1915, asked Alvin S. Johnson, an economics professor from Cornell University, to make a study or survey of the American Carnegie libraries. His report, which followed a ten week tour of the United States from east to west with visits to a hundred Carnegie libraries of varying size and character, was submitted to the Carnegie Corporation in 1916.1 It was never officially published. Johnson’s philosophy of both the purpose and methodology of what he called “library establishment” diverged so entirely from that of Bertram that it was impossible for the Corporation to adopt his Report’s recommendations as long as Bertram remained Secretary.

Johnson summarized his views of the Carnegie building program in his autobiography, Pioneer’s Progress:

Andrew Carnegie had been more passionate about libraries than about anything else in his whole private life, and in his will he had made colossal provision for the building of libraries. Fifty millions had gone into the venture, and the corporation had never even inquired how the libraries were functioning. A community applied for a library: the corporation examined the figures for population and, according to the figures, made a grant of ten, fifteen, twenty-five, or fifty thousand, with the stipulation that the community should supply every year fifteen2 per cent of the grant in maintenance. The service was administered by James Bertram, employee and friend of Andrew Carnegie, who after Carnegie’s death made a sort of religion out of planting libraries. The only control he ever exercised was over the architectural plans, which he tried to have uniform from Bangor, Maine, to Calexico, California.3

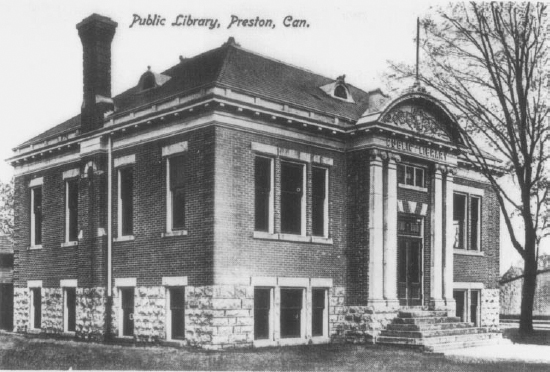

Preston Carnegie library. Picture post cards were frequently used to express a community’s pride in its Carnegie library.

Carnegie Portrait engraved in crystal.

In the report itself, Johnson first discussed the relationship of the free public library to social or public services, concluding that the library was an essential part of a system of advanced education. Moreover, he emphasized that business, industry, the professions and the trades, including agriculture, depended on access to the technical literature. However, he then questioned why philanthropist funds were necessary or should even be considered to relieve the local authorities from providing what was so essential a public service. While admitting that such funds had been and would continue to be important in the less advanced states such as Alabama, or even in less sophisticated small communities in the better developed Eastern States, Johnson concluded that it was time to shift support, for the most part, from library buildings to library services. In this regard he felt that a key issue was library personnel, noting that a good building with a bad librarian was likely to represent waste of capital. He stated that he had not found one well-managed library without a trained librarian. In a separate section of the report Johnson dealt with the necessity for improvement in library education and training as well as an increase in facilities and scholarships, and recommended that Carnegie funds be channelled in this direction rather than to buildings.

In his discussion of the Carnegie buildings themselves Johnson did not hesitate in stating that the controls imposed by the Carnegie Corporation had resulted in the later buildings displaying remarkable adaption to the requirements of economy and efficiency. Noting that since those controls had gained the disapprobation of both architects and builders, he surmised that relaxation would lead to a return to the type of library building characterized by an imposing exterior, large halls of no value for library purposes, lecture rooms and galleries supposed in a vague way to reflect credit upon the town. He identified specific Carnegie libraries, such as that in Fort Worth, Texas, which were “half waste” as far as genuine library purposes were concerned. Unused rotundas (it would appear) were not limited to Sarnia or Brantford.

Johnson also suggested that the differing characteristics of a local community should be reflected in the distribution of floor space; one library might need a large children’s area, while another might require a technical reference library. Flexibility in allowing the allocation of space to library functions was therefore of prime importance. He endorsed the concept of flexibility with respect to the combination of other community services in the library—the composite library to which Bertram had so ardently objected.

Another characteristic of the Carnegie libraries which Johnson identified as a problem in the United States was with the provision of a site. Advocating that a public library should be located on a major traffic route near the heart of the business or commercial district of the community, Johnson described some libraries which had been placed in locations where the average citizen simply would not venture. Worse, he stated, were some which people would go out of their way to avoid. He concluded that only ten per cent of the American Carnegie library sites were well chosen and regretted that more control had not been exerted over this circumstance.

Finally, Johnson pointed out that many of the Carnegie libraries had been neglected—in spite of the pledge of maintenance. Moreover, he argued that the ten per cent (of the total building cost) requested was inadequate, in the most part, to provide support as required. His summation of his recommendations, included in his autobiography, is very brief, as is his description of the inevitable confrontation with Bertram:

First, I recommended the setting up, by the corporation, of a machinery for bringing in, every year, a detailed report of the operations of all existing Carnegie libraries.

Second, no more libraries to be planted except after a thorough survey of the community, its sentiments, its needs, its realization of the importance of trained library service, and its willingness to pay for service.

Third, divert as much as practicable of available library funds to the promotion and support of library training.4

The confrontation followed, with Johnson describing how Bertram “swung his hatchet:”

Your proposals, Doctor Johnson, fly straight in the face of Mr. Carnegie’s intentions. He wanted to give libraries to communities and leave the communities absolutely free to manage them any way they might see fit. He abominated centralized, bureaucratic control. That is exactly what you want to introduce.

Mr. Carnegie never wanted an unnecessary cent to be spent in the administration of his charities. I have administered the whole huge enterprise of establishing libraries with just one secretary, with a desk in my room. To do what you propose would require twelve secretaries and at least six rooms—a big unnecessary expense.

Johnson fought back: “Not so huge an expense, I ventured to say, for keeping track of an investment of fifty millions.” “A big expense, and unnecessary,” Mr. Bertram reiterated. “And as for library training, Mr. Carnegie never believed in it. He believed in having books where anybody could get hold of them. What made him, he used to say, was a private library a philanthropic gentleman opened to him. A librarian’s business is to hand out the books. That doesn’t require a long, expensive training.”5

No further discussion was allowed at the meeting, and although the Board did move to terminate the building grants a year later, Johnson’s Report was never accepted. It wasn’t until the next decade (in the 1920’s), with Bertram’s influence less in evidence, that Johnson’s recommendations about library education were implemented by the Carnegie Corporation, and funds were channelled to the establishment of library schools; to support of the American Library Association; and for library service demonstration projects of various kinds.

Many conclusions or recommendations similar to Johnson’s are contained in the reports or letters of the Ontario Public Library Inspectors. T.W.H. Leavitt identified the importance of trained librarians as early as 1908, suggesting that Library Boards which neglected to become familiar with modern methodologies through the Library Institutes which made training available should have their provincial grants terminated. He described the new librarian as one who had ceased to be a mere custodian concerned with the purchase and preservation of musty volumes and who had become the head of a business undertaking. Leavitt also believed the public library to be crucial to the development of the community and the state, providing much more than a mere collection of books, but rather a combination of social and civilizing forces. He, like Johnson, felt that more grants, whether government or philanthropic, were not the answer for an increased awareness of the necessity of library service or for that service itself. He also preferred that the local community discover for itself the benefit of library service, and suggested that any government grants should be related to results, with impartial judges assisting in those assessments.

W.R. Nursey continued the emphasis on library training in his reports to the Minister of Education, including in a list of his 1909 duties, two items:

The direction of the attention of incompetents, (librarians) of which there are too many, to the only summer school in Canada as yet established for their special benefit, viz., the McGill Summer School for Librarians, in Montreal;

The devising of some plan for opening a similar school in the Province of Ontario.6

An analysis of the suitability of the Ontario Carnegie library sites or of the buildings themselves, similar to Johnson’s, was not made by any of the Inspectors during the Carnegie grant period. However, descriptions of individual libraries included in their annual reports do contain specific comments about the buildings. Most severe is the 1906 critique of the Goderich Carnegie Library, which identified the following defects:

No provision made for increasing capacity of stack room;

In severe weather one furnace is not sufficient;

The building [plan] is defective; the librarian is not able to see into the reading rooms from the delivery desk.7

The Brockville Library was criticized because “The roof is a trifle too flat for the Canadian winter; and a door from the basement should have been provided.”8 Defects in the Lindsay Library were also noted:

The basement is too deep in the ground, giving the building a low appearance, as the site is flat, although slightly terraced immediately around the building.

The smoking room is not properly ventilated.

The reading room is not large enough to allow for the growth of the town. This may be overcome somewhat by throwing the present reading room, the main hall and children’s room into one general room, extending the width of the building. While complete as at present, the plan does not seem to admit of further enlargement.

The heating apparatus was not of sufficient capacity. This has been partially remedied by the installation of extra radiators.9

It is of some interest that none of these Ontario critiques make mention of the wasteful rotundas or domes or of the over-generous lecture rooms about which the Johnson Report was so critical.

Johnson’s criticism of the American library sites does not fully apply to the Ontario Carnegie libraries. As mentioned earlier, the Ontario libraries, almost without exception, were located in the heart of the town or village commercial and civic government area. In spite of changes which the past seven decades have brought to each community it is most common to find the Carnegie Library, next to the Town Hall or the Fire Station and near the local shops. Only the size of a few of the original sites, limited from expansion by a river (Galt), or too close to lot lines (Fort William and Hespeler) have created serious problems.

Whether or not the Ontario libraries were more successful in their arrangements or services than those in the United States did not influence either the Johnson report or the subsequent action of the Carnegie Corporation. The library building grant programme officially ended in November, 1917, with no new grants made after that time, either in the United States or the Commonwealth. Only those communities, such as Gravenhurst or Welland, where the gift process was already well underway, received their grants and completed their library buildings after 1917.

Evaluations of the Carnegie building grants and their impact on the development of public library services in the United States have been made periodically since the grants ended. In the thirties a European assessment of the American programme concluded that the Carnegie buildings had caused an increased understanding of the significance of public library service.10 Somewhat later, an American librarian, Ralph Munn, disagreed, suggesting that “many millions of Americans have known only these small village and town Carnegie libraries and have formed their entire concept of the public library from them.” He concluded that “These libraries, too small to provide even the minimum essentials of good service, have been in part responsible for the attitude of benevolent apathy with which so many people regard public libraries.”11

The official view of the Carnegie Corporation is that the many small libraries scattered around the world created a generation of library users willing to vote for local or federal support for improved library services.12 Carnegie library authority George Bobinski endorses this view in the American context:

, . . Carnegie’s philanthropy widened the acceptance of the principle of local government responsibility for the public library. The method of giving was not perfect. Poor sites were often selected. The ten per cent support pledge was sometimes broken or more often not surpassed. Nevertheless, it was a wise provision. It placed pressure on government bodies and the public to accept the organization and maintenance of the public library as a governmental service.13

Bobinski, in his study, Carnegie Libraries, also provides an assessment of the architecture of the buildings, dismissing derogatory comments as generally referring to the older buildings built before the Corporation and James Bertram had instituted controls. He feels that the architectural memorandum issued by Bertram in 1911 led to more open, flexible and less elaborate buildings and was the beginning of modern library architecture.14

An assessment of the Carnegie grant programme in the United Kingdom, similar to the Johnson study, was conducted shortly after responsibility for the library building programme there had been assigned to the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust. Dr. W.G.S. Adams, Professor of Political Theory and Institutions at Oxford, submitted a report to the Trust in 1914 after a six month evaluation of the United Kingdom library scene. He concluded that the grants had exercised a far reaching influence on the library movement, making possible in many centres a development which would not otherwise have come into existence. “The Carnegie grants have brought home the idea of the free public library as an important local institution,” he stated. But he added: “The chief criticism concerns grants made to centres which have been unwilling or unable to support a library on the scale Mr. Carnegie provided. It may be summed up in the word ‘overbuilding’.”15

A similar analysis made in 1969 by James G. Olle suggests that the library support legislation in force in the United Kingdom at the time of the Carnegie grants was a great part of the problem, and that, on balance, money was saved for many communities through provision of a free building. He concluded that Carnegie and Bertram should not be blamed for the lack of distinction in architectural design, pointing out that they “tried to discourage extravagance in design and useless architectural features.”16

Looking back on the two decades of Andrew Carnegie’s library benefaction in Ontario, the criticisms frequently heard at the time, most often directed at the source of his wealth or the personal motivation for his philanthropy, have little relevance. More recent criticism usually relates to the inability of the smaller community to support an independent library. Experience has shown that it is increasingly more efficient for that small community to be served as part of a county or regional system. It could be argued that without their own Carnegie building some communities would have more willingly become part of such a network. The success of Carnegie libraries as branches of various Ontario County or Regional systems supports the view, however, that the buildings need not be hindrances to the coordination of library services.

Other current criticisms relate to Carnegie library plans and architecture. As discussed earlier, access problems caused by long flights of stairs, the necessity for supervision of two small floors rather than one larger one, and the inflexibility of the very early buildings with their separate rooms and delivery halls, have led to problems in adapting to modern building or library standards. The Toronto renovation initiative, among others, has demonstrated that these difficulties can be surmounted successfully. Hundreds of gifted librarians have used initiative and innovation to extend the service capabilities of the Ontario Carnegie libraries, and the incredible use that Bertram’s “effective accommodation” encouraged in buildings, both monumental and modest, also attests to their success.

The free public library movement was firmly established in Ontario prior to the Carnegie grants. The Department of Education already provided incentives for library development and growth, for library education and training, and for resources. Inspector Leavitt pointed out in 1908 that the grants made for library purposes by the Ontario Legislature compared “more than favourably with those made by the most progressive State Legislations in the neighboring Republic.”17 As their initial response to the Carnegie Corporation indicated, all 105 of the Ontario communities (including Weston, Mimico and Toronto Junction) which received Carnegie grants already had libraries, either public or free public, prior to applying for a Carnegie building.

However, the reports and letters of the Public Library Inspectors reveal that the possibility of a free building acted as a catalyst in some communities for speeding the adoption by Council of the Public Libraries Act. In other communities, with the free public library already considered an essential element of local government, the Carnegie building provided a focus for increased support for library services. Rivalry to secure a Carnegie Library among neighbouring communities or within a county, as has been demonstrated, heightened the awareness of library development, particularly in rural Ontario. The publicity—and in some instances controversy—which surrounded each step of the grant seeking, site selection and plan approval process, also helped to spread the message of Andrew Carnegie’s dramatic philanthropy. A debt of gratitude is owed to him and to the Carnegie Corporation: the present Ontario library scene, without the impetus which the library building programme created, would not be as positive. For many, many thousands of users, whether in an urban environment or travelling from the farm for Saturday shopping, the libraries represented—and continue to provide—education, opportunity and adventure, a necessary stability and permanence. The Carnegie Library was” the best gift,” and it is a heritage that must not be lost.