A “DECISIVE VOTING BLOC” IN 2012

With Loren Collingwood, Justin Gross, and Francisco Pedraza

In 2012 the Latino vote made history.* For the first time ever, Latinos accounted for one in ten votes cast nationwide in the presidential election, and Obama recorded the highest ever vote total for any presidential candidate among Latinos, at 75%.1 Also for the first time ever, the Latino vote directly accounted for the margin of victory—simply put, without Latino votes, Obama would have lost the election to Romney (at least in the popular vote). Indeed, the day after the election dozens of newspaper headlines proclaimed 2012 the “Latino tide” and lamented the GOP’s undeniable “Latino problem.” As Eliseo Foley wrote on the Huffington Post site, “The margins are likely bigger than ever before, and bad news for the GOP. . . . ‘Republicans are going to have to have a real serious conversation with themselves,’ said Eliseo Medina, an immigration reform advocate and secretary-treasurer of the Service Employees International Union. ‘They need to repair their relationship with our community. . . . They can wave goodbye to us if they don’t get right with Latinos.’”2

TABLE 8.1 Latino Contribution to National and State Margins for Obama, 2012

However, the performance of Latino voters in 2012 had not been guaranteed. Early in 2012, many journalists, campaign consultants, and scholars had questioned whether Obama would be able to win over Latinos. Would the struggling economy and the lack of progress on immigration reform result in millions of disaffected Latino voters?

It was not until the summer of 2012 that Obama solidified his image as a champion of immigrant rights, and at the same time Romney solidified his own image as out of touch with working-class families and, even worse, as anti-immigrant. From the summer to the fall, Obama stuck to a script of extensive, ethnic-based outreach to Latinos while Romney, in hopes of winning more conservative white votes, continued to oppose popular policies like the DREAM Act. The result, of course, was the worst showing ever for a Republican candidate among Latino voters.

Among Latino voters, Barack Obama outpaced Mitt Romney by a margin of 75% to 23% in the 2012 election—the highest rate of support ever among Latinos for any Democratic presidential candidate.3 While turnout declined nationally from 2008 to 2012 (by 2%), among Latinos there was a 28% increase in votes cast in 2012 (from 9.7 million to 12.5 million), and Obama further increased his vote share among Latinos in 2012 compared to 2008.4

However, this outcome was not a foregone conclusion: many theories circulated after 2009 suggesting that the Latino vote might be under-whelming in 2012.5 Given the high rate of Latino unemployment and the record number of immigrant deportations during Obama’s first administration, why did he do so well?6 Latinos’ historic party identification with the Democratic Party was strong evidence that Obama would win a majority of Latino votes.7 The other indicators, however, such as age, resources, and connections to politics, pointed toward lower turnout and less enthusiastic support for Obama.8 As late as September 2012, a common headline in the popular press was something along the lines of “Latinos’ Enthusiasm Gap Worries Dems,” and there was widespread concern that the Latino vote seemed to be “fading.”9

In the end, post-election media accounts of the 2012 Latino vote suggested that Obama performed so well among Latino voters precisely because of their unique demographic characteristics: Latino voters are younger than average voters (younger voters tend to vote Democratic), they have lower-than-average incomes (historically, poorer voters side with Democrats), and, perhaps as a result, they tend to identify as Democrats.10 Others have suggested that Obama did so well among Latinos because he supported the DREAM Act and initiated an executive order (DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) that authorized immigration officials to practice “prosecutorial discretion” toward undocumented Latino youth.11 Finally, some activist organizations have also suggested that Romney’s move to the right on immigration had a negative impact on his campaign among the Latino electorate.12

This chapter puts these accounts to the test. The 2012 Latino vote may be explained in large part by traditional vote-choice models, which include items such as partisanship, political ideology, gender, age, religion, presidential approval, views on the economy, and most important issues. These models have “worked” for fifty years, from The American Voter by Angus Campbell and his colleagues (1960) to The American Voter Revisited by Michael Lewis-Beck and his team of researchers more recently (2008).13 As we detailed the 2008 election in Chapter 6, however, we demonstrated that traditional models of voting don’t work quite as well for understanding Latino voting patterns. Further, as the electorate continues to diversify, scholars need to begin to ask how vote-choice models can be improved to better explain minority vote choice.

As it was in 2008, a critical part of the story in 2012 was Latino group solidarity, this time better stimulated by the extensive debate over immigration in the GOP primaries and through the general election season. When minority voters turned out at rates higher than anticipated by most seasoned election experts, scholars, following on the theorizing of Michael Dawson, attributed this to the strength of group identification and a common belief in a shared political destiny—what Dawson calls “linked fate.”14 His argument is that group identity shapes and structures political behavior by serving as an organizing principle for engaging the various issues at stake in the political system—in short, it is an “ideology.” While white voters may put a premium on sociotropic evaluations of the economy—how good the economy is for people in general, not just for themselves individually—the candidate who can best tap into minority voters’ shared identity and improve those voters’ perception that the candidate is “on their side” should do best.

TABLE 8.2 The Importance of Immigration and the Economy to Latinos in 2012

![]()

Source: For the Latino Decisions tracking poll, respondents were asked, “What are the most important issues facing the Hispanic community that you think Congress and the President should address?” For the Gallup weekly poll, respondents were asked, “What is the most important problem facing the nation?”

![]()

Indeed, existing research suggests that ethnic identification, ethnic attachment, and ethnic appeals may be an especially salient feature of minority politics.15 Even when the candidate is of a different race, scholars have shown, certain appeals may work to tap into voters’ sense of shared identity. In what is coined “messenger politics,” some researchers have found, for instance, that using Latino campaign volunteers in mobilization efforts can improve GOP prospects at the national level.16 Both Ricardo Ramírez and Melissa Michelson find similar evidence that Latino voters are more susceptible to coethnic get-out-the-vote drives.17 So a new lens is needed to understand not just minority politics but all of American politics in the twenty-first century.

THE ECONOMY AND IMMIGRATION, 2008–2012

In the wake of the Great Recession that began in December 2007, numerous reports detailed the disproportionate impact of the economic downturn on Latinos.18 By the end of 2008, only one year into the recession, one in ten Latino homeowners reported that they had missed a mortgage payment or been unable to make a full payment.19 Compounding the problems created by unemployment and home-ownership insecurity, by 2009 Latinos had sustained greater asset losses relative to both whites and blacks.20 By 2011 Hispanics registered record levels of poverty in general, and especially among children.21

For these reasons and others, from 2011 through 2012 the economy was consistently the most important issue identified in our surveys by Latino respondents, and this remained true right up to the election (see Table 8.2). What is most interesting about that data point, however, is how misleading it turned out to be. Decision-makers in both campaigns thought that Latinos’ concern about the economy meant that the immigration issue had faded for them; in fact, it remained a foundational issue for many Latino voters.

Concurrent with these economic patterns were major immigration enforcement efforts that were having a negative impact on Latino communities across the country. Chief among these efforts were the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) memorandums of agreement and “Secure Communities” programs, which marked an unprecedented shift in immigration enforcement from preventing entrance at the US-Mexico border to focusing heavily on enforcement and expulsion within the interior of the United States.22

The fact that comprehensive immigration reform did not even make it onto the president’s active agenda during the first two years of his administration was widely viewed as a broken promise. By early 2011, against the backdrop of this record enforcement and the failure of the Senate to invoke cloture on the DREAM Act in September 2010, the Latino community was deeply unhappy. Though the Obama campaign repeatedly claimed that it was the economy that would cement Latinos to his cause, his campaign staff understood that they had a public relations problem. Even as the administration repeatedly claimed to have no choice but to aggressively enforce the law, the activist community just as repeatedly demanded some form of action to lessen the devastating impact of deportations, then approaching 1.2 million.

In May 2010, Obama traveled to the border to deliver a speech on immigration reform in El Paso, Texas. The White House billed this event as a reboot of the immigration reform push, and it was coupled with several high-profile and well-covered meetings on the issue, but Latino voters were not buying it. In a June 2011 poll of Latino registered voters by Latino Decisions, 51% felt that the president was getting “serious about immigration reform,” but another 41% felt that he was “saying what Hispanics want to hear because the election is approaching.” He received 67% of the Latino vote when he was elected in 2008, but now only 49% were committed to voting for his reelection. The president simply didn’t enjoy the trust he once had with the Latino electorate, at least not on this issue.

Perhaps most importantly, this poll showed that huge majorities of Latino voters supported the president taking action alone to slow the deportations, and almost three-quarters (74%) said that they favored the administration halting deportations of anyone who hadn’t committed a crime and was married to a US citizen. Support was similar for protecting other groups of undocumented persons.

The administration’s repeated claims that they could do nothing administratively to provide relief from the deportation crisis were similarly rejected. At the 2011 convention of the National Council of La Raza, a speech by the president became an occasion for direct confrontation. When the president took the podium, DREAMers rose in the audience wearing T-shirts that said Obama Deports DREAMers. When the president again said that he was powerless to act, the crowd rose to their feet and began chanting, “Yes you can,” a bitter recycling of the president’s 2008 campaign slogan—which itself was, ironically, the English-language translation of the slogan of the Chicano and farmworkers’ movements of the 1960s, Sí se puede.

This more or less constant barrage of bad news with potentially significant political impact finally moved the administration. On August 18, 2011, the administration issued what has come to be referred to as the “prosecutorial discretion” directive. Based on a memo dated June 17—when the president was insisting that he had no room to act—the directive instructed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and ICE officials to use more discretion in selecting cases for deportation. The memo was further refined on August 23, particularly in relation to parents and other caregivers.

Most immigration advocates would say that this memo and the subsequent interpretations and administrative instructions had little practical effect, and indeed, by late May 2012 the Latino community was still deeply disaffected. The administration took constant heat from Univision anchor Jorge Ramos and others in Latino media. Ramos asked the president directly why he had deported so many immigrants who had families, even children, in the United States. Even Congressman Luis Gutiérrez, the first prominent Latino politician to endorse Obama back in 2007, publicly questioned whether Latinos should give their votes to Obama in early 2012. And Latino enthusiasm remained very low. In February, Latino Decisions found that the “certain to vote for Obama” share of the Latino electorate had dropped further, to 43%.

As they had done in July 2011, the DREAMers stepped into action. After quietly and not so quietly threatening to take action against the Obama campaign, two DREAM-eligible young people staged a sit-down hunger strike at the Obama campaign office in Denver. They ended their strike on June 13, but not without the National Immigrant Youth Alliance (NIYA) announcing plans to stage civil disobedience protest actions at Obama and Democratic offices across the country. They hoped the visual of minority youth being hauled away from Democratic offices would move the president to act—a stark change from the images of energetic and enthusiastic young people and college students supporting the 2008 Obama campaign.

And as he had done in 2011, Obama acted. On June 15, 2012, two days after the end of the hunger strike and the same week as NIYA’s announcement, the Obama administration announced DACA—Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Within existing legal constraints, the president issued a directive that prevented the deportation of youth who would otherwise have been eligible to stay if the DREAM Act had passed.

This action was a double win for the Obama campaign. First, there was huge Latino support for the decision, and it was immediately reflected in polling numbers for Obama. Within days of the announcement, Latino Decisions—which, serendipitously, was in the field with a poll right as the policy was announced—found an increase in support for the president and in enthusiasm for the election.

Second, since the DACA directive announced by the president was an administrative order issued by an executive agency, Romney had to decide whether, if elected president, he would allow it to continue or halt it. When asked, Romney eventually stated that his administration would not participate in the deferred action policy and instead would ask Congress to take up a permanent solution to immigration issues, a position reiterated by the Romney campaign in the last week of October.

During the GOP primaries, every candidate except Texas governor Rick Perry clamored to be the most right-wing and hard-line opponent of immigration reform and the DREAM Act. In a GOP debate, Romney himself offered the most infamous preferred policy—“self-deportation.” The implication was that he favored a policy regime that would make life so miserable and difficult for undocumented immigrants that they would simply choose to leave rather than continue to live under such harsh rules. Most observers assumed that, once the nomination was secure, Romney would tack left on this idea and on other policy issues to appeal to a general election audience. But forces in the party, and indeed his own inner circle, made any such movement impossible.

In spite of all this attention on the immigration front, the economy continued to be the “most important” election issue. So how can we reconcile Latinos’ economic fears—supposedly their most critical concern—with their eventual enthusiastic support for the incumbent? Did immigration concerns prevail over the economy in the minds of Latino voters?

To begin, it is critical to understand that many Americans didn’t blame President Obama for the crushing economic times and the immigration enforcement efforts and did not lay political responsibility for these issues wholly at the feet of his administration. Conventional accounts of the economic voter insist that “it’s the economy” that matters, and that the incumbent presidential candidate gets blamed in poor economic times.23 It could be that Latinos did not see the economy as particularly bad for themselves (the so-called pocketbook view) or for other Latinos (the sociotropic view). However, survey data indicate that the disproportionate impact of both economic issues and immigration policy on Latinos was not lost on Latinos themselves. Reports from the Pew Hispanic Center in 2011 indicate that a “majority of Latinos (54%) believe that the economic downturn that began in 2007 has been harder on them than on other groups in America.”24

In other words, the real toll of the economic recession on Latino employment, homeownership, and wealth and the adverse impact on Latinos of border and interior immigration enforcement had not escaped Latino awareness. In sum, it was reasonable to expect that, in November 2012, Latino voters would go to the polls with good reasons to punish Democrats in general, and President Obama in particular.

So why, when Latinos should have been especially prone to retrospective economic voting and when they also had expressed real concern about the immigration enforcement targeting their community, did they support the Democratic ticket? While President Obama was certainly responsible in the minds of Latinos for the historic levels of immigration enforcement, by July 2012 two key developments related to immigration served as correctives to the perceptions among Latinos that Democrats were hostile toward their community. The first was the Supreme Court decision on Arizona v. United States, and the second was DACA, the executive order on “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.” Latinos credited Obama and the Democrats with both the judicial outcome and the executive order that provided key relief for the Latino community. The shift in the perception of Democrats as hostile to seeing them as “welcoming” sharpened the contrast with the Republican Party. As Mitt Romney called for “self-deportation” and referred to Arizona as a “model” state for immigration policy below the federal level, the hostility they perceived in the Republican “brand” only increased for the Latino community.

Although the Great Recession provided the central backdrop for the 2012 election cycle, the specter of record levels of deportations, coupled with the salience of the Supreme Court case deciding the role of sub-national actors in the enforcement of immigration policy, reduced the centrality of economic issues for Latino voters in a way not seen among non-Latino voters.

THE 2012 CAMPAIGN

As campaigns have become more technologically sophisticated, they have fine-tuned the practice of micro-targeting specific messages or appeals to different subgroups of voters. In 2012 targeting Latinos became a significant endeavor for both presidential campaigns: in key battleground states such as Florida, Nevada, Colorado, and Virginia, Obama spent nearly $20 million on outreach to Latino voters, and Romney spent $10 million. Some researchers have found that campaigns that target Latino voters with ethnically salient get-out-the-vote appeals win more Latino votes.25 Data on campaign advertising also reveal that Spanish-language television and radio advertising can increase Latino turnout.26 The outreach efforts during the 2012 campaign were hardly “by the book,” however, nor were they equal in their effort. To understand why ethnically based messaging mattered so much in 2012, we first take a cursory look at the outreach efforts of the Obama and Romney campaigns.

In direct contrast to the 2008 election, in which Latino voters were fought over state by state in a competitive and long-lasting Democratic primary contest, the 2012 election included a Republican primary contest in which Latinos often felt under attack. Attempting to attract what they perceived as an anti-immigrant voting bloc in the conservative primary elections, the leading Republican candidates took a very hard-line stance against undocumented immigrants, bilingual education, and bilingual voting materials. Most importantly, Mitt Romney, who feared being called a moderate by the more conservative primary candidates, staked out a firm, unwavering, and unforgiving position on immigration. As mentioned earlier, Romney said that he would address the issue of the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States through a policy of “self-deportation.” In repeated follow-up interviews and debates, when asked what self-deportation actually meant, Romney explained that he wanted to institute a series of laws that would crack down on unauthorized immigrants by making it so impossible for them to work that, unable to make ends meet, they would have no choice but to “self-deport” to escape their miserable lives in America. While this may have sounded reasonable to some Republican primary voters, Romney’s “self-deportation” statement and continued explanations of the policy sounded ridiculous to most Latinos. On November 7, 2012, the day after the election, Latina Republican strategist Ana Navarro quipped via Twitter that looking at the exit poll data for Latinos, “Romney just self-deported himself from the White House.”

The “self-deportation” comment was not Romney’s only trouble with Latinos. During a presidential debate, he said that he would “veto the DREAM Act.” About the same time, Romney named Kris Kobach, the Kansas secretary of state, as his principal adviser on immigration. Kobach was the architect of the Arizona SB 1070 anti-immigrant legislation (see Chapter 7) and had a hand in crafting copycat legislation in Alabama; he is widely despised by Latino activists. In addition to his close connections with Kobach, Romney appeared in photographs alongside Sheriff Joe Arpaio, the law enforcement officer from Maricopa County, Arizona, who perhaps more than other figure today embodies anti-immigrant and anti-Latino policy. Nationally known (and under Justice Department investigation) for his outlandish policies, Arpaio has publicly embraced racial profiling, consistently uses bias in making arrests, persists in using excessive force against Latino inmates, and has failed to investigate more than 400 sex crimes.27 Besides associating with Arpaio, Romney called the myriad anti-immigrant legislative initiatives in Arizona, during a primary debate in that state, a model for the nation and said that he wanted to implement mandatory “e-verify,” a workplace program that would crack down on undocumented immigrant workers.

When Romney finally wrapped up the Republican nomination, the many who predicted that he would moderate his views on immigration pointed to the several high-profile Latino Republicans he appointed to his advisory committee and then dispatched to speak on his behalf. Even these surrogates, however, were often at odds with the official statements issued by Romney or by the Republican Party. Speaking to Univision anchor Jorge Ramos during the Republican National Convention, Romney supporter Carlos Gutierrez, former secretary of the Treasury under George W. Bush, agreed with Ramos that the official Republican platform ratified at the convention was troubling to many Latinos. The platform endorsed more Arizona-style anti-immigrant legislation and called for an end to the Fourteenth Amendment, which affirmed citizenship for anyone born in the United States. Republicans vowed to strip citizenship from children born in the United States if their parents were undocumented immigrants. Gutierrez struggled to explain to Ramos and his viewers that Latinos should pay no attention to the Republican platform—whose positions on immigration he called “minor administrative matters”—and that the real choice was the candidate, Mitt Romney.

Romney had two chances to make inroads with Latinos in 2012, both of which he squandered. First, the US Supreme Court heard arguments on the constitutionality of the Arizona SB 1070 law, which authorized state and local police to ask anyone they suspected of being in the country illegally for proof of citizenship, and which was decried as racial profiling against all Latinos. President Obama spoke out firmly against SB 1070, and in fact it was the Obama Department of Justice that sued the state of Arizona. When the Supreme Court ruled that three of the four provisions in the Arizona law were not constitutional but allowed the fourth provision—the one allowing police to ask for proof of citizenship—Romney issued a statement that he opposed the federal government’s interference in states’ rights and believed that Arizona should have the freedom to enact its own laws. In contrast, Obama commended the Supreme Court for striking down three-quarters of the Arizona law and vowed that his Department of Justice would continue fighting the fourth provision until it too was overturned. Obama called the law an attack on all Latinos that had to be stopped. Romney continued to refer reporters to his statement that states should be free to pursue their own laws.

As discussed earlier, the final and ultimately most critical moment for Latino outreach was the DACA policy. When Latino registered voters were queried on their social connectedness to undocumented immigrants, a full 60% said that they personally knew someone who was undocumented, and one-sixth of them said that someone in their family was undocumented. While the Obama administration’s deferred action policy was greeted with full-throated enthusiasm by Latino voters, Romney opposed it.

Eager to deflect the heat from the immigration issue and salvage any possibility of nudging Latino voters into the Republican column, Romney stressed the connections between the economy under Obama’s administration and the financial stress so many Latinos were experiencing. In a preemptive effort to counter President Obama’s message to Latino leaders in early June 2012, Romney issued a statement, with accompanying graphics, declaring that Latino economic fortunes had faltered during the president’s administration.28 Romney’s strategy was to draw attention to the high unemployment rate, increased poverty levels, and lower median household incomes among Latinos.29

OUR SURVEY EXPERIMENT

To test our predictions about the importance of the immigration issue for Latino voters, we fielded a survey experiment during the 2012 presidential election campaign among Latino registered voters in five battleground states. From June 12 to June 21, we asked respondents whether a candidate’s position on immigration would make them more or less likely to support that candidate (see Table 8.3).30

Although numerous immigration cues have been tested by campaigns and studied by academics, including the effects of using the term “illegal” versus the term “undocumented” and emphasizing cultural threats over economic threats, we focus on generic candidate statements perceived as welcoming or hostile toward immigrants.31 A large body of research has documented the centrality of emotions in political evaluations.32 Our manipulation of immigration statements here cuts to the core of the affective dimension of the immigration debate.

The descriptive results of the survey experiment are presented in Table 8.3 with observations for all of the five battleground states combined and also broken down by state. The respondents who received the welcoming immigration message broke three to one toward offering more support for the candidate. At the lower end, in Colorado and Virginia, the welcoming message garnered 56% and 58% “more likely” support, respectively. At the upper end, Arizona candidates with a welcoming message marshaled 65% “more likely” support, and for Florida candidates it was 71%.

In sharp contrast to this pattern, only 17% of Latinos overall were more likely to support a candidate who staked a position hostile to immigrants. While the proportion of Latinos who were “more likely to support” a candidate with a welcoming message ranged from 56% to 71%, the range for a candidate with a hostile message was bracketed by a low of 12% in Arizona and a maximum of 21% in Florida. Assuming voter-candidate congruence on the issue of the economy, a welcoming cue had a net effect of +64 points in mobilizing Latino support (the difference between “less likely to support” and “more likely to support”).

TABLE 8.3 Responses to Candidate Statements on Immigration in Five Battleground States in the 2012 Election

![]()

Source: Latino Decisions/America’s Voice, Five Battleground States Survey, June 2012.

Note: Figures shown are column percentages. Data are weighted to reflect Latino statewide demographics.

Perhaps more telling than the positive mobilizing effect of a welcoming message were the differences we observed in the proportion of Latinos who were less likely to support a candidate. Assuming that the response “less likely to support” is an expression of lower enthusiasm, we note that the divide is especially stark by immigration cue. Among Latinos exposed to the welcoming immigration message, an overall 3% indicated that they were less likely to support the candidate, compared to nearly half of them (49%) who gave this response when cued with a hostile immigration message. In other words, even when a candidate holds a position on the economy shared by the Latino voter, his or her use of a hostile cue on immigration will have a net effect of -32 points.33

In short, a welcoming immigration message brings two of three Latino voters into a candidate’s fold, but a hostile immigration message leaves a candidate with only one in six Latino voters who are “more likely” to offer support.34 If turnout from the perspective of a campaign is about rallying voters to the ballot box, then an unwelcoming immigration message is counterproductive to a Latino mobilization strategy because it saps away enthusiasm for the candidate. Based on these data collected in June 2012, we find it remarkably clear that the Republican candidate’s strategy as a restrictionist on immigration would be problematic for his prospects in keeping Latino support that November, even assuming that many Latino voters agreed with his solutions for the economy.35

We turn next to our attempt to better capture the importance of the economy and immigration to Latinos by using attitudinal measures about key policy statements from the two candidates, incumbent Barack Obama and challenger Mitt Romney.

ANTI- VS. PRO-IMMIGRANT RHETORIC

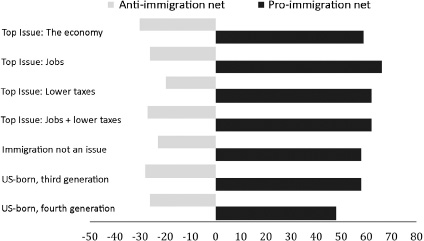

Starting from the results reported in Table 8.3, we looked to see whether the effect of anti-immigrant rhetoric versus more welcoming messages could be observed in specific subgroups of the Latino electorate. For example, we might have expected that Latinos who said fixing the economy was the number-one issue would be less persuaded by a candidate’s rhetoric on immigration policy so long as they agreed with that candidate on the economy. In fact, just the opposite was true. Even for Latinos who said fixing the economy or creating jobs was their top concern in the 2012 election, hearing an anti-immigrant statement made them far less likely to support even a candidate with whom they agreed on the economy. This result is striking because this group of voters just reported at the start of the survey that the economy and jobs were their number-one issue of concern.

FIGURE 8.1 The Net Effect of Immigration Statements on Candidate Support, 2012

![]()

Source: Latino Decisions election eve survey, 2012.

![]()

The same trend held for Latinos who did not mention immigration as either their first or second most important issue. Yet when confronted with either anti-immigrant or pro-immigrant statements, this group was also strongly responsive to the immigrant messaging.

Finally, we find the same strong trends holding for US-born third- and fourth-generation Latinos—those for whom immigration is not part of their immediate family’s Latino identity. Still, these US-born third- and fourth-generation Latinos were very persuaded by what candidates said on immigration in 2012—even beyond the candidates’ positions on the economy.

Despite finishing second to the economy as the burning issue of concern to Latino voters, immigration proved to be a critical—if not the critical—issue of the November 2012 election. Even years of inaction on immigration by the Obama administration—and worse, years of the adverse actions reflected in breathtaking deportation rates—coupled with a persistently slow recovery from a recession that was devastating in the Latino community were not enough, in the end, to move the Latino vote into the GOP column.

This surprising resilience from the Obama campaign can be credited, in our view, to three key factors. First, as we showed in Chapter 3 and again here, Latinos consistently trust Democrats over Republicans when it comes to securing their economic interests. A year out from the election, in November 2011, Latinos still blamed George W. Bush, not Barack Obama, for their economic troubles. And they placed greater trust in the president and his co-partisans to lead them back to prosperity.

This economic effect was no doubt aided by Latinos’ considerable preference for a government that addresses economic trials rather than relying on the free market. That Latinos are progressive and believe that government should solve problems made an economic appeal from the Romney camp that much harder to sell.

Second, despite his administration’s terrible record on deportations, Obama took two giant steps toward recovering his position on the issue of immigration. The prosecutorial discretion memos in the summer of 2011 can be understood as the administration finally coming to grips with the importance of the issue to the president’s political prospects. Aiding this effort were courageous DREAMers, outspoken and committed immigration activists, and some clever polling. More importantly, further DREAM activism resulted in the more effective DACA program. More than any other event in the 2012 campaign, DACA signaled the turnaround of the Obama relationship with Latino voters.

Finally, the most reliable weapon in any Democratic campaign to mobilize Latinos sprang into action—the Republican Party. Republican primary candidates pushed the party further and further to the right on immigration, to the point that the most moderate candidate in the field—and the eventual nominee—embraced a policy of making 11 million people miserable in hopes of driving them out of the country. How unsurprising that this policy was off-putting to the spouses, children, neighbors, and coworkers of those he hoped to drive away.

MULTIPLE VISIONS OF LATINO VOTING INFLUENCE

As discussed in Chapter 6, asking whether Latinos can “single-handedly” determine an electoral outcome is too stringent a definition of influence. Instead, we have considered three dimensions in measuring Latino electoral influence: state-specific demographics, including group size and growth rate; electoral volatility with respect to registration, partisanship, and turnout; and the degree of resource mobilization. Among the relevant factors are the rates of party registration, the pre-election polls of vote intention, targeted Latino campaign spending, media coverage of Latino voters within a state, estimated turnout rates, the overall size of the Latino population, and the group’s growth rate. Taken together, these factors help explain where and when Latinos are influential in presidential politics.

In his 2013 book Mobilizing Opportunities, Ricardo Ramírez takes a holistic approach to analyzing the power and influence of the Latino electorate, focusing on state-level context and mobilization efforts and asking about the nature of Latino influence across different states. He asks the basic question: were Latino voters—or some other group of voters—actually influential in the election outcomes? One approach to answering this question has been called the “pivotal vote” thesis; Ramírez rightly takes issue with it for being too results- or outcome-driven. Our view is that, although this may be but one among several important ways to understand group-based political power, the search for “pivotal blocs” will continue to have considerable appeal in media accounts of elections as well as within campaigns themselves. So we consider the pivotal vote thesis here, though we are careful to make some important improvements and caveats, per Ramírez’ recommendations in Mobilizing Opportunities.

There are two fundamental ways in which a campaign can help its candidate: getting potential voters to actually show up and vote, and convincing likely voters to cast a ballot in favor of their candidate. These tasks are not equivalent in their relative merits, nor do they remain constant throughout a campaign or among different candidates. Candidates spend time and resources reaching out to different subgroups of voters, and they have different approaches in different states. Not only do campaigns take different approaches, but some may go so far as to try to demobilize or suppress the vote. Here we take an expanded view of what it means for Latinos to be influential and provide examples of candidates and campaigns expending significant resources vis-à-vis the Latino electorate.

The fact that some noncompetitive states are Latino-heavy presents an obstacle to effectively assessing Latino voting influence. How could Latinos possibly be so influential in presidential politics if they are concentrated in California, New York, Texas, and Illinois, which are not battleground states? As FiveThirtyEight.com analyst Nate Silver stated in 2012, “Almost 40 percent of the Hispanic vote was in one of just two states—California and Texas—that don’t look to be at all competitive this year.”36 However, the question to ask is not what percentage of all Latinos are in competitive states, but rather what percentage of voters in competitive states are Latino and whether the margin of victory is likely to make this group crucial to the outcome. To the extent that many Latinos across the nation share some important concerns, the fact that a growing share of all voters are Latino in Nevada, Colorado, Florida, and even new destinations such as North Carolina, Virginia, Ohio, and Iowa, and therefore could have significant electoral influence, suggests that Latinos do matter—even if Latinos in California, New York, or Illinois do not matter at all.

Louis DeSipio and Rodolfo de la Garza asked how electoral outcomes would differ under alternative scenarios, but this is the wrong approach.37 Instead, we replace their somewhat narrow, deterministic notions of influence with probability-based assessments for each state and for an election as a whole. Rather than simply asking whether a state’s choice for president would have been different in the absence of Latino voters, we ask: how likely is it that a set of states will all have votes close enough that they will fall into a range of plausible Latino influence and so the winner of the election will hinge in turn on these states?

To capture the range of plausible influence in our model, we consider two realistic scenarios that are the best for each candidate. For instance, within each state, what was a plausible level of Latino voter turnout and percentage of Latino votes cast for Romney that would have been optimal from Romney’s point of view, and what combination would have been optimal for Obama? Then we determine the probability of an election outcome falling somewhere between these two plausible extremes. Once the election is over, the analysis remains essentially the same, except that instead of asking how likely it is that the election was decided by a set of Latino-influence states, we ask about the probability of such an outcome, in retrospect, given what we know now.

Campaign strategy is driven by a clear assessment of which scenarios are more or less likely, and a post-election reassessment must similarly deal with probabilities. Thus, while some speculate on how different history might have been if the 2000 Gore campaign had expended a little effort to train the elderly Jewish voters of Palm Beach County in how to read the now-infamous “butterfly ballot,” few would think of this small group of voters as singularly influential; we recognize the situation in Florida in 2000 as unique, since it arose from the confluence of an enormous number of systematic and random factors.

Using the best information available, the question of group influence becomes: what was the probability that the Electoral College vote and the vote margins within the states would be such that the group of interest might be deemed a decisive factor? When we compare the relative influence of Latinos and African Americans, as well as the combined influence of both groups, in the 2012 presidential election, this is the question we’re answering.

To illustrate the dynamic of Latino influence in the 2012 presidential election we created an interactive website that allows users to visualize what Latino influence looks like.38 Combining real-time weekly polling data from every state for both Latinos and non-Latinos with the estimated share of all voters who will be Latino, website users can see what would have happened if Latino turnout had been somewhat lower or higher than expected, if the candidates had gotten more or less voter support than expected, or both. If Latino turnout had been somewhat low in Colorado, or Latino voters had broken more heavily for Romney in Florida, how would the overall Electoral College have changed? From interacting with this Latino influence map, it becomes quite apparent that the Latino vote had major implications for the outcome of the 2012 Electoral College. Had Latino voter turnout rates been somewhat lower, Virginia and Colorado would have gone to Romney. Had Latinos in Florida or New Mexico leaned more toward Romney, Obama would have lost both states. The Latino vote map at the website shows these different scenarios from the 2012 election.

In many of these same states, African Americans were also a large factor in election outcomes. Had black voter turnout been lower, Obama would have lost Virginia and Pennsylvania. Because both minority groups were targeted extensively by the Obama campaign, we think it makes sense to assess both Latino and black influence in 2012, as well as the combined Latino and black influence.

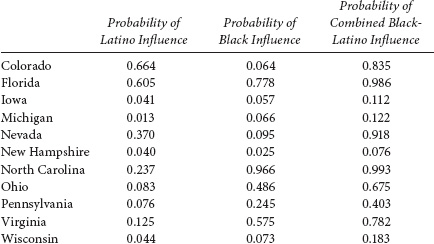

Given the data populating our Latino vote map, and drawing on the work of the political scientist Andrew Gelman, we have assessed the influence of Latinos and African Americans on the election outcome in every single state; we provide a combined minority influence score for some states in Table 8.4.39

Table 8.4 reports our results from 10,000 statistical simulations on the actual outcome of the 2012 election, in selected states, and calculates the proportion of simulations in which each state’s voting puts it in the interval of voting power for Latinos, for African Americans, and for Latinos combined with African Americans. Nevada exemplifies the potential synergy between Latinos and African Americans better than any other state: the probability of combined influence is over 90%, well more than the sum of the individual probabilities of influence. We find similar stories of Latino and black influence in Florida, Colorado, North Carolina, and Virginia, where the probability of minorities swinging the state result ranged from 78% to nearly 100%.

In addition to looking at these states individually, we can use the same logic to assess the probability that these Latino and black swing states were critical to the overall presidential election result. Taking these state results together, the probability that Latinos and blacks combined swung the election to Obama in 2012 was 67.5%.

TABLE 8.4 State-Level Model Estimates of the Probability that Latino Voters, African American Voters, or Latino and African American Voters Combined Were Pivotal to Battleground State Outcomes in 2012

![]()

![]()

DISCUSSION: EVALUATING LATINO VOTING INFLUENCE ON THE 2012 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

Based on the actual election day results we used in our simulation, Florida and Colorado were essential elements of Latino Electoral College voting power. In nearly every one of the simulation runs in which the outcome hinged on a set of states that were each decided within the margin of plausible Latino influence, these two states (worth thirty-eight electoral votes) were in that set. Given how closely contested Florida was, the high percentage of registered Latino voters in the state, the large number of electoral votes at stake there (twenty-nine), and the state’s relative heterogeneity in partisanship, it is hardly a surprise that Florida is currently the linchpin of Latino power. Nevada was close behind Florida and Colorado, appearing in over 90% of the simulation runs where the outcome hinged on Latino influence.

The probability of African American influence was about ten points higher than the probability of Latino influence in 2012, according to our measure; several states appeared in the pivotal set (Ohio, Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida) in at least 90% of the simulation runs decided within the margin of plausible variability for black turnout and vote choice. Together with Pennsylvania (88%), these states accounted for nearly one hundred votes in the Electoral College. Other than Florida, there was no overlap between the top Latino-influence states and the top black-influence states in 2012. And yet these results, taken together, point to the possibility of a minority coalition that could swing a presidential election outcome by making far more states potentially pivotal while producing state outcomes driven by a combined Latino and African American turnout and vote choice. In states where the power of African American or Latino voters would become manifest only in the event of a very close contest, it is much more likely that the combined numbers (and any uncertainty over those numbers) would be instrumental in a victory.

A fascinating consequence of the complementary demographic strengths of blacks and Latinos is that their voting power taken together is stronger—potentially quite a bit stronger—than the voting power of each bloc taken alone. As we reported in Table 8.3, in Wisconsin the probability of Latinos swinging the state outcome was around 4% and the same probability for blacks was around 7%, but the probability of blacks’ and Latinos’ combined influence was 18.3%. In Nevada the results are even more dramatic. While Latinos are estimated to have been pivotal with a probability of 0.37 and blacks with a probability of 0.10, the two groups taken together are far more formidable: the estimated probability that Nevada would be decided by a margin smaller than the combined plausible variability of blacks and Latinos was over 90%! Although Latino and black voters, taken separately, had between a 16% and 34% chance of being instrumental to the outcome of the 2012 presidential election, together they reached over a 60% chance of influence measured in this manner.

Without question, US Census Bureau data indicate that the population of Latino adult citizens will continue to grow across every state. Accompanying these demographic changes will be political changes as states begin to appear more competitive and attract the interest of the campaign strategists who map out strategies toward collecting 270 Electoral College votes for their candidate. The three-point margin of defeat for Democratic US Senate candidate Richard Carmona in Arizona in 2012, for example, suggests that Arizona is moving from leaning Republican to being a toss-up as 2016 approaches. As that happens, the Latino voters who account for roughly 20% of the electorate will become manifestly relevant. If Latino turnout is high, Democrats may benefit. If the GOP changes course in Arizona and courts the Latino vote with sincerity, the party may be able to keep Arizona a “leans Republican” state. Whatever the outcome, Arizona is a state to watch in 2016 and could be the newest addition to the list of battleground states with sizable Latino electorates.

Another state that has drawn a lot of recent attention because of its Latino electorate is Texas. After twenty-four consecutive years of Republican governors, Texas is emerging as a “pre-battleground” state. Although it is less likely to be competitive in 2016 than Arizona, the demographic changes in Texas are hard to discount. Civic groups that focus on voter registration and voter turnout are flooding the Lone Star State to register the 2 million Latinos who are eligible but not yet registered to vote. If these groups make even a dent in the rate of Latino voter registration, and ultimately the voter turnout rate, Texas could very quickly become fertile ground for Latino influence. In addition to the untapped potential of the Latino electorate, much has been made about the potential mobilizing power of Julian and Joaquin Castro as potential statewide candidates for governor, attorney general, or US senator in future Texas elections. With voter registration drives and a Castro on the ticket, Texas is very likely to be competitive by 2018 or 2020, and the reason will be Latino voters.

Beyond Arizona and Texas, which have quite significant Latino populations, our data suggest that Virginia, North Carolina, Iowa, Ohio, and Georgia could soon become strongly Latino-influenced. These states are now witnessing very close elections year after year, and all have a Latino citizen adult population that is growing dramatically. The potential for synergistic black-Latino power in new immigrant destination states in the South such as North Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia, as well as states in the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, such as Ohio, Iowa, and Pennsylvania, may have radical implications for the long-term future of presidential politics in the United States.

As the story of the 2012 election made clear, Republican candidates’ rhetoric and policy approaches to immigration, even in a period when economic concerns were dominating the political headlines, pose a nearly insurmountable stumbling block to the ability of the GOP to improve its electoral fortunes. Endorsing “self-deportation,” more border spending, the denial of in-state college tuition to undocumented immigrants, and “papers please” laws like SB 1070 and declaring Arizona—ground zero in the anti-immigration movement of the last few years—a “model for the nation” are policy positions that appear highly unlikely to reverse GOP fortunes among Latino voters.

In contrast, Democrats mustered a comparatively aggressive outreach campaign that included advertisements, voter mobilization, and targeted appeals. These efforts were considerably more successful after eleventh-hour changes in policy were made by the Obama administration—specifically, deferred action for DREAM-eligible young people—the Supreme Court issued its mixed ruling on SB 1070, and the Romney campaign reacted to these events. A fair evaluation of the dynamics of the 2012 campaign among Latinos, however, would concede that the GOP push was a much stronger factor than the Democratic pull, and that Latinos have yet to reveal their full political potential.

Latinos—alone and in coalition with African Americans—have gained newfound political power that, to date, has benefited Democrats almost exclusively. How this came to be and the long-term implications of the immigration issue for how Latinos will reshape the American political system are the questions to which we turn next.

![]()

*An earlier version of part of this chapter appeared online and is forthcoming in print as Loren Collingwood, Matt Barreto, and Sergio I. Garcia-Rios, “Revisiting Latino Voting: Cross-Racial Mobilization in the 2012 Election,” Political Research Quarterly (2014).