9

The Anatolian Embrace: Greeks and Armenians in Elia Kazan’s America, America

Shortly after Tom Jones won the Academy Award for best film in 1963, Henry Miller wrote to Elia Kazan: “I don’t think the film [Tom Jones] deserved so much. It was good but not great. Yours was great, but not always good.”1 Kazan later referred to America, America as his favorite film because it was “the first film that was entirely mine.”2 Not only was America, America the first full screenplay he had written, but he had first written the story as a novel, America, America, published in 1962. It was a novel that was memoiristic in its grounding in his family’s passage out of Turkey in the late nineteenth century. In the film, Kazan takes the story into the personal, doing the voice-overs of his narration himself, and he pushes the film closer to memoir than any dramatic nondocumentary film could be. Eli Wallach called it Kazan’s “last great film,” and the critic Foster Hirsch called it his greatest achievement and “one of the greatest films ever made in this country.” Although it was nominated for three Oscars and won one for best art direction, it opened to no box office and was a commercial failure.

Kazan’s voice-over in the film’s opening sequence articulates an immediate, essential historical context and a clear direction to the viewer that we are returning with him to a dramatic time and a complex place: 1896 in central Anatolian Turkey. Kazan’s personal-confessional narration runs for about sixty seconds over a black screen: “My name is Elia Kazan.” And then images of the Anatolian landscape (a snowcapped mountain, a plateau, wheat fields) as a voice cries, Allahu Akbar over the mountains, and Kazan continues: “I am a Turk by birth, a Greek by blood, and an American because my uncle made a journey. This story was told to me over the years by the old people of my family.”3

The camera keeps panning images of the Turkish interior: agrarian scenes, fields with animals being herded, a village of stone houses, a marketplace, Ottoman cavalry on horseback riding through a village. Behind Kazan’s narration, there’s the plaintive sound of a bouzouki, and then a ballad by Manos Hadjidakis—the words by the poet Nikos Gatsos (“And you, my lost, distant homeland / You will remain a caress and wound as the day breaks on the land”). Even if the words are lost in translation, the sadness and nostalgia of the song augment the poignancy of Kazan’s opening narrative:

My name is Elia Kazan. I am a Turk by birth, a Greek by blood, and an American because my uncle made a journey. This story was told to me over the years by members of my family. They remembered Anatolia, the great central plateau of Turkey in Asia. And they remembered the Mountain Aergius standing over the plain. Anatolia was the ancient homeland of the Greek and the Armenian people. But five hundred-odd years ago the land was overrun by the Turks. And from that day the Greeks and Armenians lived here but as minorities. The Greeks, subject people. The Armenians, subject people. They wore the same clothes as the Turks, the fez and the sandal, they ate the same food, suffered the heat together, used the donkey for burden. And they looked up to the same mountain, but with different feelings, for in fact, they were conqueror and conquered. The Turks had an army. The Greeks and the Armenians lived the best they could.

Kazan’s opening is not only unconventionally memoiristic but it’s a narrative that articulates a political reality situated in a history of colonized Christians in Ottoman Turkey at the end of the nineteenth century. His voice frames a story that will emerge in America, America as a boy’s epic journey out of a crumbling empire—a story about trauma, survival, and political oppression. And “its greatness,” to use Henry Miller’s words, emerges, I think, from Kazan’s ability to blend a highly stylized cinematography with frequent long, slow tracking shots of psychological intensity with expressionistic mise-en-scènes of unusual historical and anthropological texture. (The scenes and mise-en-scènes of Anatolian Greek life, the complex aerial shots of the Anatolian landscape, the camera angles that bring us into the densely layered urban culture of Constantinople are as brilliant as anything that Kazan has done.) Among the many rich color films of 1963, such as Tom Jones, Lilies of the Field, Cleopatra, Irma La Douce, The Birds, How the West Was Won, the film’s severe black-and-white cinematography was anomalous.

Foster Hirsch, who did a two-hour-and-forty-five-minute analysis of the film, almost scene by scene on a recent Warner Home Video DVD (2010), calls himself the “world’s number one champion of the film” and extols America, America as “the greatest achievement of the twentieth century’s greatest director of actors in American theater and film.” In this film, Hirsch goes on, “all of Kazan’s skills come to fruition.” It’s “a film that should claim its place in the American canon as an American masterwork.” Of all Kazan’s extraordinary films—and there are many, including Gentleman’s Agreement, On the Waterfront, A Streetcar Named Desire, A Face in the Crowd, Splendor in the Grass, East of Eden—Hirsch asserts “this is the work he is proudest of—the work that represents all his dreams of being a filmmaker.”

Although it opened to “no audience,” as Hirsch notes, and was a commercial failure, fifty years later America, America has been rediscovered in the wave of celebration of Elia Kazan’s work, and Martin Scorsese’s documentary, A Letter to Elia, was shown as part of the PBS American Masters series in May 2011. With its evocation of American exceptionalism, the film seems to have become a metonym for the American immigrant narrative. Scorsese calls it “the story of the passage of the old world to the new.” In some very basic way, America, America corroborates this metonym as it celebrates the idea of the United States as land of hope and new beginnings. Close to the end of America, America, there’s even a heart-wrenching sea voyage of poor immigrants crossing the Atlantic by ship and coming into New York Harbor, where that great indexical image of the Statue of Liberty rises up out of the fog. The TV film channel AMC recently ran the film on the Fourth of July—as one of those classics that depicts the heroism of the immigrant story and the epic journey to Ellis Island.

Although the final scenes bring us to Ellis Island and New York for the American dimension of the story, the place and location of America, America is Turkey, both the rugged Anatolian interior and the great capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul). For all the praise and scrutiny the film is now receiving, and from formidable figures like Scorsese, Wallach, Jonathan Lehr in The New Yorker, and even a film scholar like Hirsch, there is something odd and perplexing about the failure of any of its critics and champions to explain what the fundamental and boldly depicted historical story and circumstance of this film is about.

›››‹‹‹

America, America opens in 1896 in the mountainous terrain of the Anatolian plateau, near the city of Kayseri, where we encounter the protagonist, Stavros, a young Greek man in his early twenties who lives in a small village under Mt. Aergius, near Kayseri. From Kazan’s opening voice-over and the song by Hadjidakis, we cut to the ice-piled flank of Mt. Aergius, where Stavros and his best friend, the Armenian, Vartan Damadian, are hacking ice and loading it on their wagon to sell it over the mountain in their village. Kazan continues: “But the day came here in Anatolia as everywhere where there’s oppression, when people began to question. There were bursts of violence, people began to wonder, and some began to search for another home.”

As we encounter the Ottoman militia harassing Stavros and Vartan, who are carting the ice back to their village, we learn the news of a political event that has rocked the country: Armenian activists have taken over the Ottoman Bank in Constantinople, protesting the long-standing mistreatment of Christians by the government and the deep-seated discrimination in the Islamic infrastructure of Ottoman Turkey. The event, known as the Ottoman Bank Incident, results (in the film and in history) in a second round of Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s massacres of the Armenians throughout Turkey in the mid-1890s—an episode known as the Hamidian Massacres.

This violent history is both context and text for America, America, and that history generates the darkness of the film that is embodied, symbolically and aesthetically, in Kazan’s cinematic landscape of relentless, tenebrific lighting and dark mise-en-scènes. Kazan’s stylized lighting and long, slow, sometimes handheld camera shots deepen an expressionistic and psychological complexity. But darkness is the film’s modality, and it defines the texture of scene after scene in which the inner turmoil of the characters is interwoven with the oppressed condition of Christians in Turkey. Stavros is continually moving through a landscape of shadow, chiaroscuroed faces, and dark interiors in which social and psychological meanings emerge. Stavros’s family, the Topouzoglus, are a comfortable, middle-class provincial Greek family, and if conditions had been difficult for them as Christians, now the massacres of the Armenians have convinced Mr. Topouzoglu that it is time to leave Turkey.

In the early scenes, we see close-ups of Stavros and his family, their intense stares, brooding looks, dark eyes, and contorted faces, all modeled by dark shading. Darkness encompasses psychology throughout the film, and in the mottled darkness we encounter the faces of Stavros’s mother’s anguish, his father’s repressed pain, and the stoical anger of his Armenian friend Vartan. In many ways, the film is defined by Stavros’s many gazes and facial gestures of pain, anger, sadness, humiliation, and brooding; his face is haunted, scowling, silent, pained, and repressed. Over and over, and perhaps excessively, Stavros’s face is shadowed, mottled, shaded, cradled, framed by darkness—in his house in the village, in the Turkish governor’s office doorway, in his grandmother’s cave in the mountains, in raki houses and brothels, and in the hull of the ship going to America.

Dark (and sometimes black) interiors dominate the mise-en-scènes: the rooms in the Greek village house where Stavros moves in and out of his mother’s anger and his father’s fear; the almost black interior of the basement of the house where, amid the hidden family wealth, Stavros meets with his father, who exclaims: “I’ve made up my mind. We’re going to send you to Constantinople. Our family is going to leave this place and you’re going to go first”; the raki club where Stavros and Vartan dance in half dark, half light as Turkish men smoking hookahs look on; the shadowed streets of the village where Armenians are running into the dark interior of a church where they will be burned alive; the half-black interior of a brothel where the prostitutes dance as Stavros broods; the darkness of the sewers underground in Constantinople where the hamals (human pack animals for cargo) have their labor meetings; Stavros’s face encircled in darkness as he sits next to the shadow that encapsulates Mrs. Kebabian at a dance club in Istanbul; Stavros’s face, like a Caravaggio portrait, amid the dust and light of a strange basement room, where he tells his fiancée, Thomna, that he must leave her and “this land of shame” for America.

Aboard the ship, there are more dark interiors: the cabins, the passageways of third-class steerage; night through a porthole on Stavros’s face; the dramatic conversations on board happen in darkness; Stavros’s cathartic dance at night on deck; and, at Ellis Island, masses of people are slumped in half darkness inside the bars of the waiting stations.

›››‹‹‹

Once the narrative unfolds with Kazan’s opening voice-over, Armenian-Greek relationships are crucial to shaping the plot. While driving their ice cart off the mountain, Stavros asks Vartan if there are mountains bigger than this one in America, and Vartan answers: “In America everything is bigger.” As Vartan stares at the mountain, he exhorts Stavros: “What are we waiting for? Come on you, let’s go you. With the help of Jesus.” Here and later, the intense relationships between Stavros and his Armenian friends deepen both the mythic and political dramas that underscore much of the tension in the film. Both personal and cultural relationships between the Greek protagonist and his Armenian friends are enmeshed, reciprocal, and symbiotic, and his rebellious soul is drawn toward their vulnerable condition.

Vartan—the older friend whom Stavros regards “in a worshipful way” (as Kazan’s script directions indicate)—is the catalyst for what becomes Stavros’s obsession with going to America. And for Vartan, the idea of America will soon become inseparable from the political oppression of Christians in Turkey. The repeated phrase, “for the sake of Jesus” or “with the help of Jesus,” passes between Stavros and his Armenian friends as not only a prayer but also a cultural signifier that embodies both an idea of hope and the issue of religious difference that defines much of the predicament for Greeks and Armenians in Turkey.

From the time we meet the earthy, disaffected Vartan in the opening scene, Armenians become a topos, sometimes allegorical, sometimes fully realistic, and always a source of agency for Stavros’s journey out of Turkey. Armenians—even more so than Greeks at this flammable historical moment in the late 1890s—are a pariah minority, a tainted group. If Kazan has already noted in his opening voice-over that “a time comes when people begin to question,” we discover in the next scene that the Armenians have pushed the political envelope for reform by creating a national incident in setting fire to the national bank in Constantinople. Kazan has dramatized history a bit here by turning the incident into a conflagration. In fact, the Armenian activists in late summer of 1896 did not burn the bank, but they took it hostage with no intentions of violence and with the goal of calling on the European powers to intervene against the Sultan’s mass killings of the previous two years, which took the lives of more than 100,000 innocent Armenian civilians. Although a shoot-out with the Turkish authorities resulted from the bank takeover, the bank and its possessions were untouched. But, the Sultan’s response to this act of protest was to perpetrate more massacres of Armenians throughout Turkey.

Within the first three minutes of the film, Kazan has cut to a scene in the office of an Ottoman provincial governor who reads to his staff of bureaucrats a telegram from the Sultan. The voice-over tells us that the year is 1896, as the governor, an avuncular-looking man in a fez and glasses, says:

This came an hour ago over the wire from the capital. “Your Excellency on this day, the eve of our national feast of Bayram, the Armenian fanatics have dared to set fire to the national Turkish bank in Constantinople. It is the wish of our Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, the resplendent, the shadow of God on earth, that the Armenian subject people throughout this empire, be taught once and for all, that acts of terror cannot be tolerated. Our sultan has the patience of the prophet, but he has now given signs that he would be pleased if this lesson would be impressed once and for all on this dangerous minority, how this will be affected will be left up to each provincial governor and to the army post commanders in each provincial capital.”

In a scene that must have perplexed (or perhaps bypassed) most viewers in 1963, as perhaps it still does today, Kazan brings a dramatic, historical moment back from the mothballs. What did viewers make of this? Armenians? Burning a bank in Constantinople in 1896? Constantinople? Or is it Istanbul?

Kazan recalled his grandmother’s stories about hiding Armenians in her basement during the 1890s massacres. “One of the first memories I have is of sleeping in my grandmother’s bed and my grandmother telling me stories about the massacre of the Armenians, and how she and my grandfather hid Armenians in the cellar of their home.”4 Here, too, Kazan has mined the traumatic memory of his family’s experience in creating a story that involves inextricable ties between Armenians and Greeks in Turkey. The viewer who knows the broader arc of this history knows that the massacres of the 1890s were a prologue to the genocides of the Armenians and the Pontic (Black Sea region) Greeks between 1915 and 1920, and to the ethnic cleansing of Greeks from their historic homelands of western Turkey, especially Smyrna and Constantinople from 1913 through the Turkish burning of Smyrna in 1922. Kazan’s memory of his grandmother’s narrative had left its mark on him.

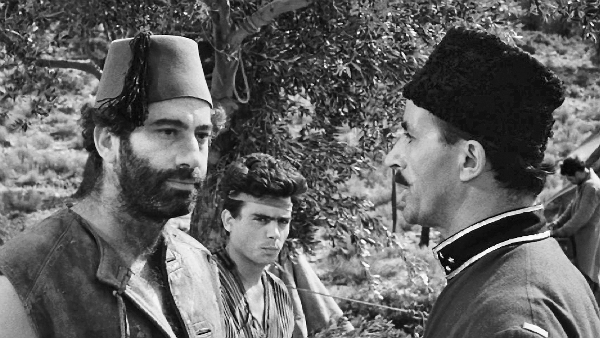

Stavros and Vartan must continually navigate the racism and infrastructural prejudice that define their public identities as Christians. On their way back to the village, Stavros and Vartan are harassed by a group of Turkish soldiers who mock them and then help themselves to the ice they’re hauling. Only when Vartan reveals to the Turkish captain Mehmet that he had been his orderly in the army years ago does Mehmet’s tone change. Calling him his “little lamb,” Captain Mehmet embraces Vartan, in the way a plantation owner in the American South might have gone nostalgic upon meeting a long-lost house slave. He warns Vartan that because of the Ottoman Bank seizure, “today no Armenian will be forgiven for being an Armenian” (Figure 1). Here, as in various scenes throughout the film, Kazan captures the nuances of racism with facial gestures and body language that are quintessential to his method-acting idiom. The Turkish captain then urges Vartan to stay with him in the mountains, but Stavros explains that Vartan must go to help protect his family in the village.

When Vartan and Stavros arrive in their village of Garmeer (the word means “red” in Armenian), Armenians are running through the streets in terror, flocking to their church for protection, and the Greeks are closing their doors and shutters. In Kazan’s passion for facial expression, he captures the terror in the haunted faces that are running, watching, hiding. Stavros is admonished by a woman to whom he is selling ice, “Don’t be seen with this Armenian.” When he returns home, he is scolded by his mother, who tells his father “he’s been with the Armenian again.” When Stavros’s father tells his friends in the family parlor that his son is close with an Armenian, he says defensively, “It’s not our affair. They are Armenians and we are Greeks. It’s their necks and not ours.” Stavros overhears this, pokes his head in the room and retorts: “True, they’re saving the Greeks for their next holiday.” The older men are made uncomfortable by the boy’s remark; Stavros has hit a nerve and has disclosed his political astuteness about the relationship between Greeks and Armenians in Turkey.

Figure 1. Elia Kazan, still from America, America (1963). “Today, no Armenian will be forgiven for being an Armenian,” says a Turkish captain (far right) to Vartan (far left) and Stavros.

In a melodramatic scene in a raki club where Stavros and Vartan do a macabre dance as the local men stare at them from the dark corners of the tavern, Vartan repeats his mantra, “Come on you, let’s go you.” Stavros answers, equally transfixed: “America, America.” Those words, uttered in a kind of haunted trance, are epithets for hope, emancipation, new life—and just then there is a cry from the street and Vartan whispers, “The jails are emptying,” signifying that the criminals have been released to start the massacre.

In an extraordinary scene and perhaps a historic representation of government-sponsored mass killing in the history of film, Kazan’s depiction of Armenians being burned alive in a village church brings his probing political realism together with his expressionistic aesthetic. When the men in the raki club shout, “It’s beginning,” we understand that the idea of massacring Armenians has a ritualistic aspect to it and that the local population has been waiting for the sign to be given. Kazan then cuts to the inside of a church where Armenians are congregated, candles and incense giving the interior a sensual mystery, as a priest is leading them in prayer. The Armenians in the church are chanting Devormyah (“Lord Have Mercy”); there’s a cutaway to Turkish gendarmes and locals surrounding the church, carrying torches and brush; then a cutaway to the interior of the church, where men, women, and children are singing as the church fills with smoke and the icons and crosses and altar are enveloped. Outside, a priest is humiliated; he fights back, and a gendarme puts a lit torch in his hand and throws the priest into the burning church. As flames engulf the church, we watch smoke fill the narthex; Armenian words and screams dissolve into flames, some people escape, and Vartan is embroiled in a fight to defend his people. Then images of smoke and fire are juxtaposed in such a way so that the scene swirls and fades to a vortex of flame and black sky, and the music crescendos in an atonal flourish (Figure 2). Kazan cuts to the smoke-covered remains of the church, the dead scattered in the streets, and Stavros sitting next to Vartan’s corpse. Foster Hirsch asserts that this scene is indicative of how “the Christian religion has failed its believers.” When I first heard his comment on the on Warner Home Video aftermath commentary, I replayed it several times to see if I heard correctly. I wondered if in viewing an image of a synagogue being burned during Krystallnacht, Hirsch would have said that it revealed how the Jewish religion had failed its believers. I think it is fair to note that this scene is not about how the Christian religion has failed its believers. Rather it is a depiction of the calculated mechanisms of state-sponsored mass killing and the assault on religious identity of a targeted minority group, and it gives us various insights about human rights atrocities.

Figure 2. Elia Kazan, still from America, America (1963). Armenians burned alive in a church set on fire by Turkish gendarmes.

Grief-stricken, Stavros drags Vartan’s body away to bury it, only to be arrested by Turkish soldiers. Forced to leave the corpse, he snatches Vartan’s fez, and after that, only his father’s bribe to the governor can buy him out of jail. Although Vartan is dead, he has become the first source of agency in Stavros’s journey, and his fez will remain an emblem of his friendship with Vartan and a symbol of his quest for America.

Almost immediately after Vartan’s death, Stavros meets a frail, tubercular, coughing young man walking barefoot on a mountain road. The man, whose name is Ohannes Gardashian, is mumbling as he walks along, begging, “I will pray for you when I get to America.” Horrified, but with pity for this waif wandering in the mountains hoping to escape Turkey, Stavros asks him how he expects to make it to America without shoes or money, and Ohannes retorts, “With the help of Jesus.” Irritated, bemused, drawn to the Armenian, Stavros gives him his own shoes and then asks him where he’s from. Ohannes gazes upward, points to the sky: “Beyond those clouds are the mountains of Armenia. I’ll never see them again.” He keeps coughing as he bids him farewell: “I’ll remember you.”

After the massacre, in an ensuing scene in which Mr. Topouzoglu must go to the governor’s office to beg for Stavros’s release, during which the governor extorts a bribe from him while lecturing him about the virtues of being a “good”—meaning subservient—Christian. Stavros looks on in horror at his father’s submissiveness, then takes off to find his grandmother in the mountains. In a scene of primal intensity, Stavros finds his grandmother in her cave-like house in the side of a mountain. She looks like a weathered crone, a tough, witty woman who disparages her son (Stavros’s father) for being a Greek coward in the face of Turkish oppression. She gives her grandson a dose of her wit: “The Turks spit in your face and they say it’s raining.” Desperate for her to help him get to Constantinople, he begs her for money, but instead she gives him a knife, which he tries to refuse until she gives him another piece of Greek wisdom: “It will remind you that no sheep ever saved himself by bleating.”

Shortly afterward, to Stavros’s shock, Mr. Topouzoglu decides it is time for the family to leave Turkey. In a dramatic scene in a dark basement room of their house, father gives son permission to leave the village for Constantinople with the family’s entire material wealth and possessions. He confesses to his son the humiliation he has endured as a Christian in Turkey: “From time to time, I have had to do things . . . well, we live by the mercy of the Turks. But I have also kept my honor safe inside me. Safe, inside me. And you see we are still living. After a time you don’t feel the shame.” Stavros stares at his father, his face half swallowed in darkness—smooth and cherubic, hardened and sour as his father whispers, “It’s our last hope.”

›››‹‹‹

In sending Stavros by donkey to Constantinople with the family wealth to join his cousin in the rug business before he makes his passage to America, Kazan commences the picaresque sequence of the film. Stavros is not unlike Pip or Huck Finn in his initiation into adult complexity as he navigates a sinuous, obstacle-laden path that tests his character and courage. Episode after episode, his journey across Anatolia to the great capital city is a baptism into violence, thievery, extortion, and corruption—a journey into the bowels of Ottoman society and its institutions. At one point near the end of the film, as he explains himself in a moment of crisis, Stavros exclaims: “I have been beaten, robbed, shot, left for dead. I have eaten the Sultan’s garbage, and driven the dogs off to get at it. I became a hamal.”

And from the start, he is robbed by a Turkish ferryman, befriended by a Turkish con artist, Abdul, who calls Stavros “brother” as he extorts his money and family possessions, spending it on prostitutes and raki in exchange for protecting him. After Stavros is fleeced by a prostitute at a brothel, Abdul accuses him of having stolen his possessions and takes him to an Islamic court because, under Ottoman law, by swearing on the Qur’an his word is sacred against a Christian’s; in court, Stavros is fleeced of everything. As in Gentleman’s Agreement and On the Waterfront, Kazan’s interest in corruption, bigotry, and social infrastructures is explored with uncanny power.

Again and again, Kazan depicts the harsh realities of being Christian in Ottoman society with his documentary and psychological realism. In the next scene, Abdul taunts Stavros: “I envy you—you Greeks have learned how to swallow insult and indignity and turn around and smile.” The legacy of shame that Stavros’s father articulated (and that Kazan noted about his own father) keeps building, and after trying to steal Stavros’s last coins, Abdul continues to taunt him (“are you any different from sheep, they won’t fight for their lives either”). This finally provokes Stavros to use the knife his grandmother gave him, and he attacks Abdul as he kneels for his evening prayers; a fight ensues, and the murder happens below the cliff and off camera.

In Constantinople, Stavros is plunged into a world of cruelty and poverty. Because he’s arrived penniless, his cousin refuses him a place in the business and tries to convince him to court a young Greek girl from a wealthy family. Stavros rejects the idea and is then forced to become a hamal. After more calamities befall him, his fellow hamal, Garbed, convinces him to join an underground labor movement, and when Garbed exclaims, “The main victims of the Turkish Empire are the Turkish people,” Kazan deepens his political vision to encompass subaltern life in Turkey and the conditions of the working class. Kazan’s ability to get hold of the edgy undersides of poverty yields a sequence of scenes among the devastating conditions of Constantinople’s hamals and prostitutes and other marginal segments of Turkish society. After Stavros miraculously survives the Turkish police massacre of the members of the labor movement at their secret meeting underground in the sewers, he takes his cousin’s advice; he gets himself a suit of good clothes and becomes a suitor of one of the daughters of the wealthy Greek rug merchant, Aleko Sinnikoglou.

As the texture of the mise-en-scène changes radically, Kazan takes us through elaborate rituals of courtship in a wealthy Greek Constantinople family, where we witness the stratification of power and gender roles between patriarchal men (especially the pasha-like father) and encounter Kazan’s rich mise-en-scènes of bourgeois life. The cinematography of Haskell Wexler and the editing of Dede Allen are inventive and scrupulous in ways that give the film a gritty realism that is enmeshed with lyrical, symbolistic, and metaphoric meanings. Stavros is betrothed to Sinnikoglou’s eldest daughter, and although he appears to be headed for a life of affluence and familial comfort, at a crucial moment and in an uncharacteristic burst of passion, he confesses to his fiancée, Thomna, that an inner vision compels him to leave all this good fortune for America:

I don’t want to be my father. I don’t want to be your father. I don’t want to have that good family life. That good family life! All the good people they stay here and live in this shame. The churchgoers who give to the poor live in this shame.

In what is an evolving trope that began with his father’s confession about the humiliation and shame that are inseparable from being a Christian in Turkey, here Stavros breaks through the mask and confesses that he can’t live in this society where Christians live in terror or, to use Ralph Ellison’s trope—in invisibility. On the threshold of inheriting the prosperous Sinnikoglou carpet company, his quest for America is reignited and, once again, Armenians become sources of agency.

At his prospective father-in-law’s rug store, Stavros meets Harutiun Kebabian, a wealthy Armenian American rug merchant, and his wife, Sophia, who was born in Constantinople but left at eighteen to marry. Elegant and sensual, Sophia, married to an elderly husband whose only interests are money, lives in frustrated desperation. She tells Stavros: “My twenty-second year is still inside me waiting like a baby to be born.” In initiating an affair with Stavros, she pulls him closer to America. At her apartment he looks longingly at catalogs of American fashion; he tries on her husband’s straw hat, fantasizing about New York. After Sophia has helped Stavros secure passage aboard the ship to New York, her husband learns of their affair, and an altercation erupts between Mr. Kebabian and Stavros. Stavros is charged with criminal assault and ordered to be deported upon arriving at Ellis Island.

As desperate as Stavros’s situation seems, there is still an Armenian in the wings to bail him out. That mysterious tubercular man, Ohannes Gardashian, to whom Stavros gave his shoes on the mountain road in Anatolia, has made it to Constantinople, and Stavros befriends him again, becoming his protector, giving him money and food. Ohannes has boarded the ship to America as one of the shoeshine boys who are being sponsored by a Greek American businessman. Aboard ship too, Stavros takes Ohannes under his wing, getting him food and coaching him on how to suppress his tubercular cough so he won’t be sent back to Turkey by the Ellis Island health officials.

After the altercation with the rug merchant Kebabian, Stavros knows his future is jeopardized, and he tries to join Mr. Agnostis’s shoeshine boys but is rebuffed because he has no sponsorship. When Ohannes butts in, saying: “Take my name. I beg you. Take Ohannes Gardashian,” Mr. Agnostis reminds him that there can’t be two Ohannes Gardashians on board. In an ensuing moment of carnivalistic apotheosis, Ohannes and Stavros find themselves on the ship’s prow at night with the lights of New York in the distance. When Stavros threatens to jump overboard and swim ashore, Ohannes, knowing the impossibility of his surviving, implores him not to. Kazan then cuts to a scene of young wealthy Americans celebrating the ship’s arrival; party lights, a band, cocktails, and dancing create a counter scene to the immigrant drama going on near the railing. Stavros looks on from a shadowy corner of the deck, then leaps into the celebratory arena and does a wild, gyrating dance in which he screams a primal scream—what might be seen as a cathartic unburdening of the cumulative pain (and perhaps a cry of collective historical rage, too) he has endured through his journey from his village in Anatolia to this liminal place on board a ship approaching Ellis Island.

The Americans look on, bemused and ignorant, like characters in a Fitzgerald scene, laughing in their evening attire with drinks in their hands. And while all this is happening, Ohannes has silently walked to the railing of the ship and jumped. From the moment we were introduced to this gentle, ethereal young man walking in the Anatolian highlands—pointing to the clouds and the Armenian mountains to the east—he has seemed a sacrificial figure and, to use the cliché, but one that works here in a larger Christian context, a Christ figure.

When we see Stavros next, he has joined Mr. Agnostis’s shoeshine boys and is in line at Ellis Island’s immigration desk, now using the Armenian name Ohannes Gardashian, whose papers have been given to him by Agnostis. With some comic Ellis Island realism, Kazan has the customs official Americanize the name from Ohan-nes to Joe Arness, and so, through the agency and sacrifice of his Armenian friend Ohannes Gardashian, Stavros Topouzoglu is reborn Joe Arness—a new American in the land of hope. However, Armenian agency is not over, and as Stavros walks off the dock, Bertha, the Kebabians’ maid, comes running up to him with an envelope from Sophia that contains a substantial sum of cash to aid him in his first weeks in the New World.

As the movie closes, Kazan splits the screen between the old and the new—a Turkish village and Manhattan. In New York, Stavros/Joe is shining shoes; then Stavros’s family, in their village, receive a letter from him. “In some ways it’s not different here,” Stavros writes, and as his father looks around with a sense of paranoia, he says to his wife, “How quickly he’s forgotten what it is here!” “But let me tell you one thing,” Stavros writes. “You have a new chance here! For everyone that is able to get here, there is a fresh start. So get ready. You’re all coming. I’m working for that. To bring you all here, one by one.”

The scene shifts back to Manhattan, where Stavros is shining shoes and tossing a newly earned coin in the air, saying, “Come on you, let’s go you,” and now the words “people waiting” replace Vartan’s epithet, “with the help of Jesus.” In another cutaway back to the Topouzoglu home, the camera pans the faces of the family looking out on the town as a squadron of Turkish cavalry ride past their house. The sound of the hooves is loud, the force of the militia echoes loudly, and Stavros in a voice-over is saying, “people waiting, people waiting.” Kazan intercuts an image of the Flatiron Building in Manhattan, then to Stavros hurrying up his customers in that mode of American entrepreneurial hustle. Then Kazan cuts to Mt. Aergius in the Anatolian highlands, as the juxtaposition of the land of shame and the land of possibility create a metonym for the whole story.

›››‹‹‹

Why has the central historical structure of the film been left out, ignored, or possibly self-censured by critics, admirers, and journalists alike? The persecution of the Greeks and Armenians by the Ottoman Turkish government is the animating force that propels the story, makes the film’s concept possible. It’s curious that none of the cultural, journalistic, or commercial framing of the film, whether it be on AMC, in The New Yorker, or in the new Warner Home Video package, even notes, let alone represents, this history. Warner video presents a narrative on the DVD cover stating that Stavros “leaves his war-torn homeland behind to begin a new life.” Even the most uninformed viewer might ask: What war was this? The informed viewer might ask: If the film’s subject were the pogroms of the Jews in eastern Poland and western Russia in 1900, would Warner Home Video present the historical event as a war? John Lahr in The New Yorker quotes Kazan’s memorable opening voice-over about Armenians and Greeks being subjugated minorities, and then notes that the Kazan family left the capital of Turkey (it was still Constantinople then) for New York but never mentions why the family left. Lahr goes on to note that Kazan’s father was intensely anxious and once told his son, “Say nothing, don’t mix in.” And he quotes Kazan recalling, “I was kept segregated . . . it’s the segregation a minority imposes on itself . . . but it was really the result of terror.”5 Wouldn’t it seem an organic continuation of Lahr’s narrative to mention something about “the terror” that inflected Kazan’s father’s behavior and the terror that Elia makes explicit note of? Why did this Greek man who grew up in Turkey in the late nineteenth century convey a sense of terror to his son? In the era of genocide and trauma studies, surely these are not rarefied issues and questions. Since Lahr quotes Kazan in conversation with French film historian Michel Ciment, it seems likely that he would have read on in the interview. Kazan’s reflection on his own family past in Turkey explains the impact of the Armenian massacres in his family’s memory and his sense of the entwined lives of Armenians and Greeks in Turkey:

The Anatolian Greeks are a completely terrorized people. My father’s family comes from the interior of Asia Minor, from a city called Kayseri, and they never forgot they were part of a minority. They were surrounded with periodic slaughters—or riots: the Turks would suddenly have a crisis and massacre a lot of Armenians, or they’d run wild and kill a lot of Greeks. The Greeks stayed in their houses. The fronts of the houses were almost barricaded, the windows shut with wooden shutters. One of the first memories I have is of sleeping in my grandmother’s bed and my grandmother telling me stories about the massacre of the Armenians, and how she and my grandfather hid Armenians in the cellar of their home.6

The film historian Foster Hirsch spends nearly three hours explicating the film in the DVD after-segment, and at least notes, even if in passing, that Kazan created at the outset “a complicated political context” in which Greeks and the Armenians were an oppressed minority in Turkey. But—it would have been appropriate for him to have explained to the viewer just a bit about what that complicated political context was. He makes no mention of the Hamidian Massacres, the event that is the guiding catalyst of the story. And it might have been of interest to the viewer of this film to know that the Hamidian Massacres made an impact in the United States in the 1890s to such an extent that the atrocities were widely reported in the press, and a nationwide relief and rescue movement ensued. Clara Barton took the first Red Cross mission ever out of the country when she led her teams to the Armenian sections of Turkey in 1896.7 This was America’s first international philanthropic rescue effort, and its impact on American history was significant. In the year which Kazan sets his story, Harper’s magazine ran an illustrated cover story of Armenians being hunted down by killing bands.

There are some startling intersections between the film’s narrative and the process of its making, and in his autobiography Kazan writes about the ordeal of filming the opening of America, America in Turkey in 1962. It was personal and historical irony that Kazan made his own journey back to the city of his birth, to a place and culture of which he had almost no personal memory, having left Istanbul in 1913 at the age of four, when it was still called Constantinople. Being in Istanbul in 1962 was not too distant from the Istanbul of September 1955, when the massacre and expulsion of most of the Greek community of the city occurred, in what became the final episode in Turkey’s cleansing of its historic Greek population. Tens of thousands of Greeks were killed, and thousands of Greek businesses, private properties, and churches were destroyed or confiscated. Even though the military coup of 1960 had been supplanted by a constitution in 1961, Turkey was still an authoritarian society where Kemalist militarism was still congruent in many ways with late Ottoman nationalism, and state repression of intellectual freedom still left the jails full of writers, journalists, and ethnic minorities. Minority rights continued to be nonexistent, and with the Greek and Armenian communities destroyed, more than ten million Kurds were not only disallowed civil rights, but were not allowed to call themselves Kurds and forced to use the term “mountain Turks.”

From the start, Kazan was required to go before the Turkish censorship board in Ankara to have his script evaluated for anything that might be unacceptable, or anti-Turkish. In anticipation, Kazan admits to having cut any scenes he thought would be offensive to the government. His description of being interrogated by five men, two of them in army uniforms, in a government office, captures some of the Kafka-like bureaucracy he encountered. Although the censors had read the script, “they weren’t certain what their opinions were,” Kazan recalls, because no one wanted to let a seditious movie through if it might offend the higher bureaucrats. However, eager to bring half a million U.S. dollars into their economy, the censors went back and forth until, finally, the head of the censorship board told Kazan that if he were to shoot in Turkey, he would have a government official at his side each day to monitor each scene.

When Kazan tactfully assented, the director of the censorship board replied: “Our pasha hopes you are sincere. But as they say in your country, talk is cheap. What we must expect of you is a film masterpiece that will show our people not as they are shamefully portrayed in American films but as they are in truth, honest and hard-working, with great love for their soil and for Allah.” Kazan replied: “That is precisely my intention.” 8

Filming street scenes in Istanbul, Kazan recalls feeling a kind of fear that wasn’t so different from what his father had conveyed to him about being Greek in Turkey. Having already written Stavros’s story and now in the place of his birth and his character’s life, he recalls: “I was still afraid of Turks and would never get over it.” One Turkish newspaper reported that Kazan had come “to shame the Turkish people,” and, as Kazan put it, “The effect of this accusation was intensified by my fearful imagination. Besides, it was close to the truth.”9 Having already developed the trope of Turkey as “a land of shame” in his script, Kazan’s return to his birthplace seemed to be overlapping with the traumatic life of his protagonist in that very place, sixty-five years later.

When Kazan’s cousin Stellio came to watch scenes being filmed in downtown Istanbul, he looked on from far away, kept walking, and never acknowledged his famous American cousin. As Kazan watched his cousin scuttle between buildings, afraid to be seen near the set or him, it brought him to a moment of recognition: “If George Kazan had not brought his wife and two sons to America in 1913, I could have been there now, dressed as my cousin was dressed, hustling everywhere as he hustled everywhere, ‘invisible.’ If it hadn’t been for my father’s courage—a quality I had not until that day associated with him—I’d now be what my cousin was.”10 It seemed that there, on set, on site, in the place of his birth and family’s past, Kazan experienced a self-recognition and a sense of a larger historical self and its link to history.

Although Kazan managed to appease his censor so they could, at least, start shooting, one day on site shortly afterward, as he was directing a scene that involved bargaining in a bazaar, a secret-police officer came running onto the set, screaming to the censor that this scene must be disallowed because it would show the Turkish people as overemphatic bargainers. “Why eight hands waving like that? The world will think Turkey an insane asylum.”11 As the scene was being shot, the secret-police officer fired the censor and took his place. After this, Kazan conjectured that their hotel rooms were bugged, and he and his associate producer, Charlie Maguire, now believed that the whole film company was under Turkish surveillance. “They got cops on their cops here,” Maguire told Kazan, and then confessed to him that they had only gotten this far because he had been paying daily, hefty bribes to censors and police.

The filming continued to unravel in a day-for-night way as events on and off the set dovetailed, and finally Kazan, like his protagonist Stavros, realized that he must get out of Turkey. In retrospect, he recalled that the experience of filming in Turkey was now turning out to be “a source of inspiration” for the film. Maguire convinced Kazan to shoot the rest of the film in Athens, and assured him that he had a plan to get the good footage out of the country. To dupe the customs agents and the secret police, Maguire put the exposed film into boxes marked “raw stock” and the unexposed film into boxes marked “used.” The customs agents confiscated the wrong boxes, and Kazan recalls their celebration in Athens as they sat in a hotel restaurant shaking the canisters of good film in victory and imagining the Turkish agents handing over the blank film to their superiors.12

›››‹‹‹

There is an edgy neorealist texture to this historically situated bildungsroman. In its representation of the complexities of life for Christians in Ottoman Turkey and its social-psychological realism, America, America owes something to Eisenstein’s historical epics, and also to postwar neorealism; Fellini’s La Strada, De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, and Kazan’s own On the Waterfront, for example, are among films of the era that engaged the harsh real without sentimentality.

Few feature-length Hollywood films of midcentury dealt with human rights or ethnic cleansing (the Hamidian Massacres were a prologue to a modern age of genocide, the Armenian case of 1915 being the first)13 in the telling of a boy’s coming-of-age story with such aesthetic complexity and social and psychological depth as Kazan does here. Out of a haunted passion for his family story of leaving Turkey for America, Kazan created a memoiristic film that achieved mythic dimensions in its absorption of history and culture and politics, and this is clearly why he continued to call America, America his favorite film, the one that brought his career—as a writer and director—together.

Furthermore, in its representations of ethnic difference, religious ideology, and class and its depictions of power and gender in a traditional Middle Eastern culture, Kazan anticipated certain kinds of postmodern and contemporary questioning. America, America’s depiction of working-class life, especially among the hamals and prostitutes is rendered in a dark, grainy austerity, and a tenebrific light that gives a haunting depth to this subaltern culture. We encounter the urban underclass eating garbage, living in the streets, and being massacred by the police in the sewers during their labor meeting and the brothels where women barely survive as they are exploited by pimps and owners. These scenes are shot with inventive, long, and slow camera shots, so that the texture of place and detail of culture are rendered with depth and nuance. In scenes of domestic Greek village and city life, male-dominated rituals and control over women are depicted with a psychological texture that gives us insight to the traditional culture of the time and place. Women are subservient, sometimes trapped, sometimes contentedly ensconced in the patriarchal dynamics of the culture.

Kazan, Haskell Wexler, and Dede Allen created scenes of unusual texture in depicting the great urban crossroad of Constantinople (Istanbul) with its architecture of domes and minarets, ports, restaurants, rug stores, squalid streets, sewers, and brothels that give us a sense of a complex city at a complex time. Scenes move between the sublime and mysterious Anatolian highlands and the grimy interiors of raki houses and brothels; the affluent parlors of a wealthy Constantinople Greek family and an Armenian village church going up in flames; Manhattan’s Flatiron Building and the Turkish cavalry kicking up dust in an Ottoman village. Such is the range of the film’s mise-en-scène and its cinematic reach.

America, America is a film that seems to me to speak to our contemporary concerns with even greater intensity than it might have had for a general audience in 1963. In some symbolic way, it may be a film about America, but its breadth and sweep, its unusual blend of neorealist edge and expressionistic drama, create a strange and arresting mix of historical depth, social realism, and a probing psychological portrait of a young man’s coming of age and epic journey across cultures and continents. In telling a deeply personal family story and the story of Stavros’s decent into the harsh realities of adult experience, Kazan pulled off a remarkable exploration of the politics of religious and ethnic difference, the exploitation of state power and mass violence over minorities, the violence of class conflict, and gender complexity. Few films of any era have traveled along such cultural landscapes, have embodied personal, psychological, and historical trauma, collective family memory, and mythic structures that are transformed in an expressionistic lyrical idiom that never forsakes the real.