If you have read either Leadership and Self-Deception or The Anatomy of Peace, you will be familiar with the character named Lou Herbert. The inspiration for the Lou character was a man named Jack Hauck, the founder and longtime CEO of Tubular Steel, a St. Louis–based national distributor of steel and carbon products. Tubular had engaged one of the world’s best-known consultants to help it overcome the toxic infighting that plagued the senior management team and stymied the growth of the entire company. After months of trying one approach after another without success, Jack asked this consultant if he knew of any other approach the company could try. The consultant was acquainted with Arbinger’s work and recommended that Jack explore our ideas.

During our first meeting with Jack and his team, we focused on helping each executive team member reassess his or her contribution to the challenges the company faced by carefully considering the following statement: As far as I am concerned, the problem is me.

As eager as Jack was to solve his company’s problems, he struggled early on to apply this statement to himself. “I want you all to get the message,” he said. “I’m going to have posters made and put up all over the building.” Then, pointing his finger at the assembled executives and officers, he said, “Don’t forget: As far as you are concerned, the problem is you.” Eyes rolled, and people dropped their shaking heads into their hands. It is so easy to leave oneself out of the equation when considering an organization’s problems, even without realizing one is doing so.

Even though the issues at Tubular were not simply the problems of a single person, it was clear that no problem could be solved if individuals were not willing to address how they themselves were part of the problem. If you recall the Ford story from chapter 8, you’ll remember that the unwillingness of team members to step forward and admit their contribution to the company’s problems was the primary issue that Alan Mulally had to crack before anything could improve. Given the history at Ford, turning outward seemed too personally risky at the time for most members of the leadership team—so risky, in fact, that they had, in essence, decided that they would rather the company fail than admit and address their contributions to its problems. That is, until one person was willing to make the first move and turn outward without any assurance of what others would do.

So while the goal in shifting mindsets is to get everyone turned toward each other, accomplishing this goal is possible only if people are prepared to turn their mindsets toward others with no expectation that others will change their mindsets in return.

This capability—to change the way I see and work with others regardless of whether they change—overcomes the biggest impediment to mindset change: the natural, inward-mindset inclination to wait for others to change before doing anything different oneself. This is the natural trap in organizations. Executives want employees to change, and employees wait on their leaders. Parents want change in their children, and children wait for the same in their parents. Spouses wait on change in each other.

Everyone waits.

So nothing happens.

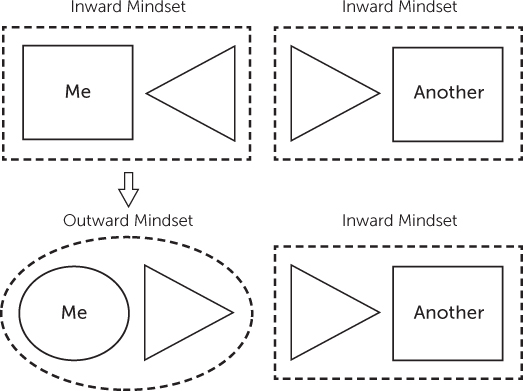

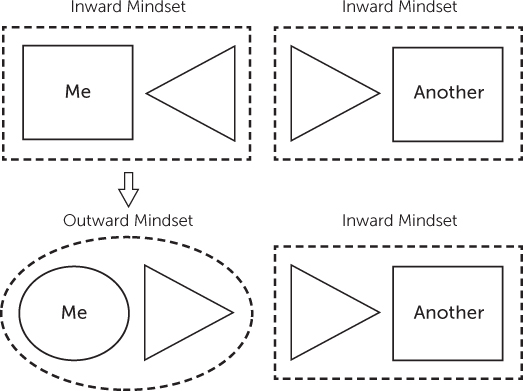

Ironically, the most important move in mindset work is to make the move one is waiting for the other to make. Diagram 14 illustrates this move.

The top of the diagram depicts two people—me and another—whose mindsets are mutually inward. Both of us have, in effect, turned our backs to the other’s needs and objectives. From this stance, each of us is waiting to be seen by the other. I want the other person to begin to see and consider me—my views, objectives and needs. On some level I may realize that the other person wants the same from me, but for the reasons discussed in chapter 5, I resist.

Diagram 14. The Most Important Move

The most important move consists of my putting down my resistance and beginning to act in the way I want the other person to act. This move is depicted in the bottom half of the diagram, which illustrates what should be the main goal of any effort to change mindset: to equip people to change their own mindsets even when others are not yet ready or willing to change theirs.

Would our organizations be better off if all of us were to turn outward in our work with each other? Yes. But this preferred state can be reached only if some are willing to change even when others do not—and to sustain the change whether or not others reciprocate.

This kind of unilateral change is the essence of true leadership. Unfortunately, those who make this move are too rare. People tend not to make this move precisely because the inwardness of those with whom they are engaged gives them all the justification they need to stay inward themselves. At Tubular, Jack Hauck’s inward mindset toward his leadership team provided them with every justification to further entrench themselves in the self-focused, protective, and frequently combative posture they had adopted. And no one was more so entrenched than Jack’s right-hand man and chief of staff, Larry Heitz.

Unbeknownst to Jack, at the time of our first meeting with the team, Larry had already made plans to leave the company. After years of dealing with Jack, he had decided that enough was enough and that Jack would never change. The only sensible choice was to move on. Since Larry had learned that the head of sales felt the same way, they had begun quietly recruiting the company’s best and brightest to defect and start a competitor organization.

Shaken by Larry’s departure, Jack began to consider how he might be complicit in the problems that plagued his company. The scrutiny he had once applied to his people, he refocused on himself. He started to change, both at home and at work.

As Larry built his new company, he heard about the efforts Jack was making to change the way he engaged with others as a leader. This caused Larry to consider all that he had learned from Jack while at Tubular—lessons that had proved vital in the success of Larry’s new company. With a promising prospective buyer for his company, Larry began to wonder what it might be like to rejoin Jack.

One year after Larry had left, he picked up the phone to call him. “Jack, it’s Larry,” he said. “I’ve been thinking a lot since I left. You’ve invested a lot in me over the years, and everything I know, I learned from you. I’ve used what you’ve taught me to build my own company, and I think I could help you turn Tubular around. I don’t know if you’d be willing to let me return, but I’d really like to come back and work together to try to save the company.”

Remarkably, Jack agreed.

Larry returned, dedicating his full-time efforts working with a small Arbinger team to develop and implement a systematic outward approach across the entire organization. As a result of this work, one person and department at a time began to turn outward. This took discipline.

One enduring fight in the company was the daily battle between the sales and credit departments. Both had a compelling story to share. (And share they did!)

The credit department, charged to keep bad debt below 2.5 percent of the company’s revenue, felt responsible to scrutinize each credit application and deny most of them. The credit team had learned to watch the salespeople carefully, knowing that in their push to get a sale they would try to slide credit risks by them, go around them to get exceptions from the executive team, or turn the application in right before the sales deadline so that there wouldn’t be enough time to research the applicant.

Of course, the problem seemed very different from the perspective of the sales team. Just as they were ready to close a big sale, the credit people would deny the customer’s application on a technicality—rules or policies that seemed ever changing and never communicated. With compensation largely tied to commissions, the sales team felt undermined at every turn.

“Don’t they get that we don’t have revenue if we don’t have sales?” the exasperated sales team would say.

“But revenue isn’t revenue if you can’t collect it,” the credit team would respond.

Like a never-ending tug-of-war, they were both pulling on separate ends of the same rope, able to achieve their department’s objectives only if the other failed to achieve theirs. Each side had justification to spare. Turning outward, it seemed, would mean losing the fight.

But for the first time in his career, Al Klein, the long-standing head of the credit department, wondered whether a fight was actually needed. “We need to be different,” he told his team at the beginning of an all-day, closed-door meeting. “I’ve set aside the entire day today to work on this, and we’re not going to leave until we figure out how we can still meet the company’s objectives regarding bad debt while enabling the sales team to be successful.”

Seeing the needs, challenges, and objectives of the sales team, Al and the credit team began to think more carefully about their role. “The sales team is selling forty different kinds of products,” one of them said. “Some are high-margin specialty products, and others are low-margin, high-volume commodities. Surely it would help not only the sales team but the company as a whole if we found ways to approve credit risks for those customers who are making high-margin specialty purchases.” Once they started thinking in this way, they devised a completely new objective: maintain bad debt at 2.5 percent of the company’s revenues in a way that helps the sales team achieve their objectives and the company realize its profitability goals. They also decided that they would check with company leadership to see if a rigid 2.5 percent approach was really best for the company. They wanted to stay open to a better approach.

This newly conceived objective, which now required the credit department to find ways to be helpful to the sales department, called forth a new level of initiative and creativity from the credit team. In less than a week after the credit department made this change, the sales team was overheard to say, “If anyone can figure out how to work with customers to help them qualify, it’s our credit team.”

Notice the similarity in the ways Jack, Larry, and Al began turning outward despite the inward provocations from others. Considering their impact on others created in each a desire to find ways to be different to improve the results of the company. When they focused on this result, it was no longer Larry versus Jack or credit versus sales. Instead, each began to think about how he might be making it more difficult for the other party to achieve the objectives that the organization required of them. Each did this on his own without requiring the same from the other party. Free of an inward mindset, each was able to see ways to overcome the challenges he had previously faced without demanding that the other reciprocate. For Jack, Larry, and Al, this was the most important move.

As Jack and Larry began focusing on the needs of the company and Al and his credit department team focused on the needs of the sales team, other people across the company began devising and implementing ways of working that were different and far more effective than anything they had ever experienced before. Within two years, Tubular was producing the best return on investment in the industry. Larry, who later succeeded Jack as president, recalled the process this way: “People figured out what they were supposed to do, not only to make their area successful but also to help people in other areas be more successful. Over the course of a few years, that made a tremendous difference to the company and produced a different kind of a culture. As a result, we grew from $30 million to over $100 million and more than quadrupled our profit during a time when the market for our products had gone from about 10 million tons down to 6 million tons. Even in a declining market, we still grew by a factor of four.”

None of these results would have happened at Tubular had Jack, Larry, and people like Al waited on others to change. Ironically, only when they gave up their demand that the other parties change were they finally able to see and act in ways that invited them to change.

A company that is committed to building an outward- mindset culture will prepare and help people to be able to make and maintain a shift to an outward mindset even when others haven’t yet made the shift. Those who persist with an inward mindset ultimately won’t be able to stay with such an organization because their staying would not be helpful to them, the organization, or their customers.

The change to an outward mindset doesn’t happen overnight. And even where such change is widespread, people who usually operate with an outward mindset will sometimes slip back to an inward mindset. Customers too may sometimes have an inward mindset. For all these reasons—as well as because widespread mindset change happens in large measure in response to those who change first—being able to operate with an outward mind-set when others do not is a critically important ability. It is the most important move.

Sometimes people are afraid to make this move because they think that others may take advantage of them if they do. But people misunderstand the most important move we are talking about if they think that working with an outward mindset when others refuse to do the same makes a person blind to reality or soft on bad behavior. It does neither. In fact, what obscures vision and exposes people to more risk is not an outward mindset, which stays fully alive to and aware of others, but an inward one, which turns its attention away from others while simultaneously provoking resistance. People who work in dangerous, high-risk situations know this most of all—people like the Navy SEALs and SWAT team members we’ve referenced before. They know that their lives and missions depend on their ability to remain fully aware of the complexities of their situations and to do so in a way that doesn’t stir up escalated resistance. The outward mindset doesn’t make them soft; it makes them smart.

A related reason why people resist making the most important move is that they think an outward mindset will make them soft when hard behavior is required. But this is a misunderstanding. As we’ve said, an outward mindset doesn’t make people soft; it just makes them open, curious, and aware. Similarly, an inward mindset doesn’t make people hard. In fact, people whose mind-sets are inward often engage in behaviors that are softer than would actually be helpful. Wanting others to think well of them (a common inward-mindset motivation), people often indulge, pacify, or placate others when direct actions would be more helpful. In contrast, parents and leaders who have a responsibility to help others improve and grow may engage in harder behaviors when their mindsets are outward. Why? Because sometimes the help a person needs is a long way from soft. Fear that an outward mindset would make one unhelpfully soft springs from a misconception of this mindset.

Fairly frequently, we encounter leaders who are paralyzed with a different kind of fear. They think that a mindset-change effort might be a good idea, but they worry about how their people will react. So these leaders dip a toe into mindset-change efforts and sit back to see how their people respond. They tell themselves that they will make the decision about whether to proceed with the effort based on the reaction of their people.

In our experience, if people see their leader just dipping a toe in, they will think, rightly, that the effort probably won’t amount to much. Consequently, the leader sees a lukewarm response in his or her people and on that basis decides that it probably isn’t worth the effort. But that same leader is blind to the biggest reason for the observed reaction: the people have a tepid response because they see the leader’s tepid response.

Remember, the principle to apply is, as far as I am concerned, the problem is me. I am the place to start. Others’ responses will depend mostly on what they see in me.

The most important move is for me to make the most im portant move.