Funny, but he doesn’t look jockish.

Except for maybe the shiner.

Striding through the concrete corridors of the Trois-Rivieres’Le Colisee, Jacques LaPrairie, 19, moves more like a model than a hockey star.

“Can you give me a few minutes to go home and fix my hair?” he asks in broken English, adding in French, “I can’t let you take my picture like this.”

Not that there’s much wrong with ‘this’—five foot six, a lithe 140 pounds, long, dark hair, velvety brown eyes, tawny skin.

But underneath it all is solid muscle and determination. The kind of determination that can carry the young goalie as far as he wants to go. *

IF YOU THINK THERE is something odd about this depiction of Jacques LaPrairie, your reaction is justified. Who would ever describe a male sports star in terms that focus exclusively on his good looks? Yet that is exactly how the real subject of this 1991 Toronto Star article—elite hockey player Manon Rhéaume—was portrayed.1 And it is how many female athletes are depicted.

Although the article excerpt may be a particularly overt example of how the media have portrayed female athletes, this kind of description is by no means uncommon. With Rhéaume’s name back in place, the article does what many features do to female athletes: it showcases the sexual attractiveness and femininity of the athlete, discussing her physical strength and skills only once her aesthetic appeal has been established. The message conveyed is that the real worth of female athletes lies not in how they perform, but in how they appear.

While the focus on the appearance of female athletes reflects the historical discomfort with celebrating the competitiveness and power of women, it also points to a deeper role that athletics play in our lives. The world of sports has traditionally been male terrain; it has provided not only a setting in which men can prove their masculinity but also a place in which their actions are glorified. The fact that even today girls and women must undertake legal battles to gain access to the sporting opportunities enjoyed by most boys and men indicates the extent to which the female presence in sport is unwelcome.

Yet the focus on the femininity of female athletes is just one of the ways in which their accomplishments are under-mined. For the most part, women are simply ignored. The sports media’s near exclusive concentration on professional male sports has ensured women’s absence on most sports pages and in television and radio broadcasts. With the exception of golf, tennis and figure skating, the vast majority of female sports fall into the larger category of amateur sports—a category that also receives meagre attention. To some extent, this accounts for the lack of reporting on women in sport. But not entirely. Even when the media do turn their attention to amateur sports such as hockey, women still receive far less recognition than do their male counterparts.

Amateur sports organizations are partly to blame for this. Many of the organizations do a poor job of getting word out to the media about their athletes and events; they often lack both the money and the savvy to hire qualified media liaison people. Money, however, isn’t always the problem. The Canadian Hockey Association (CHA) has a budget in the millions of dollars, yet has been unable to secure much in the way of media attention and sponsorship for its elite female athletes.

And so it is no coincidence that with the increasing, and increasingly serious, media coverage of women’s hockey since the first world championship in 1990 a disproportionate amount of it has focussed on Manon Rhéaume, the first woman to make the pro leagues. The predictable interest in Rhéaume is in part due to her marketable “assets,” but it is also because Rhéaume has played on men’s teams and within a male sports context—a context that the vast majority of sports reporters and corporate sponsors know and feel comfortable within. Like most women’s sports, female hockey is caught in a seemingly inescapable orbit outside the realm of the professional male game: without proper media recognition, corporations will not invest in the athletes; and without the marketing drive of a committed sponsor, the media will not take notice.

The symbiotic relationship between media and sponsorship in hockey first took shape in the early 1930s in Canada. At the time women began to be shut out of sports pages as part of the gradual exclusion of amateur sports from all media coverage. In his excellent history of amateur sports in Canada, The Struggle for Canadian Sport, Bruce Kidd chronicles the shift in media coverage from focussing on sports at the community level to focussing on professional teams. Kidd follows the formation of the National Hockey League (NHL), describing how promoters of the professional game in the 1930s left nothing to chance in replacing fans’ allegiance to community teams with loyalty to the Toronto Maple Leafs, Montreal Canadiens or American teams. “In Toronto, the Leafs management [offered] reporters pre-written features, statistical information and privileged access to stars and ‘scoops’ if they filed stories on a daily basis …” writes Kidd. “In some cases, the entrepreneurs bribed reporters outright.”2 If reporters failed to write what promoters requested, they were often cut off from information sources.

Nowhere was the reshaping of fans’ loyalty so powerful as on the radio. Foster Hewitt, the CBC announcer of Hockey Night in Canada for more than three decades, is still revered as Canada’s most beloved “voice of hockey.” What is less well known, however, is that Hewitt was on the payroll of the Maple Leaf Gardens, hired as director of radio—in essence, a paid publicist—in 1927 by the team’s owner to call its Saturday night games. Kidd rightly likens the set-up to “turning over the news department to the campaign director of one of the political parties, the music department to RCA records, or farm broadcasts to the Winnipeg Grain Exchange. One narrow, vested interest was given virtually unrestricted opportunity to define the hockey culture for us all.”3 The broadcasts were immensely popular: by 1934 the Stanley Cup semifinals blared from over 70 percent of the one million radios across Canada.4 Although the program was sponsored initially by General Motors, Imperial Oil came on as sponsor in 1936, keen to gain access to the largely male listenership.

Hewitt’s broadcasts did indeed “define hockey culture” and Canada’s interest in sports as an exclusive focus on male hockey. This happened at the expense of the many other sports that Hewitt announced over the radio in the early 1920s, including women’s basketball, softball and hockey. As Hockey Night in Canada grew to dominate sports broadcasting in Canada, women’s coverage virtually vanished from newspapers and the airwaves. Writes Kidd:

Despite the large number of men who paid to watch women’s games, it was felt that only men’s sports would attract a male audience. While girls and women listened to the Hewitt broadcasts, they did not have the spending power or perceived household influence to attract the interest of sponsors such as General Motors and Imperial Oil. As a result, the fundamental production function of the sports-media complex was designed for an all-male universe. It helped keep women’s sports off the air.5

To this day coverage of women’s sports remains scant at best. From 1991 to 1994 the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity (CAAWS) conducted informal surveys of the sports sections of twenty Canadian daily newspapers. The survey involved measuring the inches of space devoted to women’s sports stories for one day in 1991, one week in 1992 and two weeks in 1993 and 1994. In 1991 CAAWS found that women received a trifling 2.8 percent of sports coverage nationally. The Ottawa Citizen rated the highest at 12 percent, the Globe and Mail followed at 5 percent and from there the percentages dropped steadily to the lowest, 0.2 percent in the Montreal Gazette. In 1993 the overall national total of space devoted to women’s sports in the period studied was 8.8 percent.

When CAAWS released its findings to sports editors, the most common explanation proffered for the low coverage was that reports on professional male football, baseball and hockey games left little room for any amateur sports, not just women’s. However, during the 1994 baseball strike and NHL lockout, not only did the coverage of women’s sports not improve, it dropped in thirteen out of the twenty dailies to a national average of just 5 percent. The Halifax Chronicle-Herald ranked the highest at 18 percent with the St. John’s Evening Telegram coming a close second at 16 percent. The Toronto Star, Canada’s largest daily, remained at the bottom of the heap at 1 percent with Quebec’s Le Droit at 0.6 percent.

Many sports reporters and editors pointed out that the surveys were conducted in the fall, a time when summer amateur sports had just ended and major winter sports such as alpine skiing had not yet begun. Because amateur sports constitute the major sporting outlets for women, not much was going on at the time for female athletes and this was reflected in the papers. Nonetheless, rather than pause to question the enormous emphasis on professional male sports, sports section editors and reporters denied the validity of the survey or attacked CAAWS as a special interest group. Don Sellar, the Toronto Star’s ombudsman, was just one of a number of journalists to dismiss the cry from CAAWS for more coverage of female athletes as self-interest. In the Star, Sellar quotes the paper’s managing editor Lou Clancy also as being unimpressed with the survey. “I don’t believe in quantitative research,” Clancy told Sellar. “You can’t bring a feminist agenda to sports coverage.”6 David Perkins, the editor of the sports section since 1994, also did not take the survey’s results seriously. “[The] study was not based on fact. They [CAAWS] admitted themselves that it was not scientific,”7 Perkins insists. Sheila Robertson, CAAWS’s communication consultant, responds that the organization “admitted” nothing. “That annoys me,” says Robertson, “because we always said it was not scientific in the sense that we did not hire an academic to do the research. But of course it was valid. We measured the coverage very carefully, [a process that] … took hours.”8

The second article reacting to the survey came from Mary Ormsby, the only full-time female sports reporter at the Star. “A misleading one-week survey done each of the last three years annually convicts Canadian newspapers of a sex crime: Deliberately ignoring the accomplishments of female athletes,” writes Ormsby. “Nothing could be further from the truth. But that matters little when a feminist cause decides that the women-as-victims-of-men angle is the easiest way, not the best way, to build its cause.”9 Ormsby’s article is of particular interest because in it she addresses and alas, defends, the prevailing myths of why it is natural that male athletes are reported on more than female athletes. “The No. 1 priority of a newspaper is to make money,” Ormsby writes. “To do that, a newspaper responds to matters that interest the community in the hope of selling more papers. This community loves male sports (sorry, it’s a fact) and the year-round coverage of those leagues reflects that interest.”10

The assumption that the media only respond to people’s interest, and play no role in creating this interest, is seldom questioned by sports reporters and editors. But as Bruce Kidd has shown in his description of the rise of the NHL, the media have in fact shaped the public’s ideas about which teams, athletes and issues are important. “It’s a chicken and an egg thing,” says Wendy Long, the sole female sports reporter at the Vancouver Sun. “We can’t cover it unless there’s the interest, but if we gave women’s hockey the same amount of coverage, we’d be telling people that that’s important. I think the media does set the agenda about what’s important and just by how we cover things we’re sending a message to the public. [For instance,] the Vancouver Canucks play eighty-four games a season and you cannot tell me that each of those eighty-four games is the be-all and the end-all of sports that day.”11

Furthermore, this obsession with stars, scores, winning teams, and in the case of hockey, brawls, means that more relevant stories go untold—one notorious example being the non-reporting of Alan Eagleson’s alleged dubious financial dealings in hockey. Allison Griffiths, co-author of Net Worth, a book that covered some of Eagleson’s alleged shady financial deals, observes that when a reporter resists the pack mentality by writing stories that are critical of professional male sports, she or he will encounter hostility not only from the sports organizations but also from other reporters. Griffiths, who helped expose the corruption within professional hockey, speaks about the same phenomenon that Kidd describes in sports reporting in the 1930s—namely, that a reporter will be cut off from sources for not parroting the professional sports gospel. “It’s who you know and who you can get access to. If you don’t know anybody, you’re nowhere,”12 says Griffiths.

The second assertion that Ormsby makes in defending the overwhelming coverage of professional male sports is that “this community loves male sports.” Given that sports is the newspaper section that is least read by women, the parameters of the “community” to which Ormsby refers are very narrow indeed. While few studies have been done on readership of sports sections and results of these studies vary, one trend has emerged: fewer women, teenagers and children are reading the sports section than fifteen years ago. According to statistics from the Newspaper Association of America (NAA), the percentage of women who read sports dropped most dramatically. At the organization’s convention in 1994, the NAA proposed that one of the best ways to increase female readership was—amazingly enough!—to include more stories on women athletes.13 In other words the main reason that women are not picking up the sports sections of papers is not because they don’t care about sports, but because women’s sports activities aren’t reflected on those pages.

To assert that the community wants only professional male sports is all the more incomprehensible given declining readership of newspapers. Indeed, newspapers in the 1990s are under siege: the cost of newsprint is rising, advertisers are harder to woo and competition with television is proving to be a losing battle. Yet rather than attempting to appeal to a broader, more inclusive audience, sports sections editors are frantically trying to hold on to the limited readership they already have. David Langford, the sports editor at the Globe and Mail, also views the coverage of professional sports as inescapable. “Of course professional sports is going off the end of the scale,” he concedes. “People want more and more and more professional sports, so something has to lose out somewhere along the line.”14 The Toronto Star’s sports editor, Perkins, goes even further: “We don’t create the demand [for pro sports], we just reflect the demand,” he contends. “Getting the coverage to fifty-fifty [male-female] is not a realistic goal because the number-one interest of the readers is the Leafs, then the Raptors and then the Blue Jays. Those are the priority for the readers and resources.”15 Jane O’Hara, sports editor at the Ottawa Sun from 1988 to 1993, reports that while she tried to ensure that women in amateur sports received coverage equal to that given to their male counterparts, she made no attempt to curb the dominance of professional male sports at the Sun, lest she alienate the male readership.16

The next issue that Ormsby tackles in her article criticizing the CAAWS survey is the argument that many women are great fans of male sports, and “there’s no need to shovel women-only articles at them. That’s sexist.”17 It is true that many women are fans of male sports: about 50 percent of the audiences at professional basketball games are women,18 as are almost 30 percent of hockey viewers.19 Yet when there is little else available, what option do sports fans have but to watch male games? To say that it would be sexist to “shovel” women-only stories at readers is an odd assertion indeed given that Ormsby and others find little sexism in the fact that more than 90 percent of sports coverage centres on men.

Ormsby goes on to claim that the “real story is that female athletes are getting better coverage than ever.”20 While she offers no general evidence to back this up, she does rightly point out that the Star has made an effort since 1994 to feature women more frequently on the front page of its sports section. Editor Perkins says that from 1993, the number of days women were featured on the front page of the sports section rose from fifty-four to ninety-six.21 It is worth pointing out, however, that “featuring” can mean anything from printing a picture with a caption underneath to running an article. It is also worth noting that 1994 was an Olympic year, and consequently one in which amateur athletes on the whole were written about far more often than usual. Furthermore, many Canadian medal-lists in both the Olympics and the Commonwealth Games are women. Despite the large role that Canadian female athletes play in international amateur events, says Jane O’Hara, “[o]nly when amateur athletes like [Olympians] Myriam Bedard and Sylvie Frechette do really well do they bump hockey or baseball off the front pages.”22

The situation is perhaps the worst for young female athletes, who are consistently the media’s last priority. From September 1993 to April 1995, the Scarborough Board of Education in Metropolitan Toronto studied the Toronto Star and the Toronto Suns sports sections, tallying the number of articles that each paper devoted to male and female high school sports. The total number of articles on high school sports in the Star was 158, only 27 of which were on girls’ athletics. The Sun ran a total of 98 articles, 9 of which focussed on girls.23

Yet despite numbers like these, many sports journalists and editors maligned the CAAWS survey results, and in some cases even gloated over their self-perceived excellence in reporting on female athletes. “Our paper is regularly singled out for our excellent coverage of women’s sports, and I know that at any other time of the year you would find us at the top of your survey,” responded Edmonton Journal editor Wayne Moriarty, whose paper devoted a whopping 5 percent of its sports section to women athletes in 1994. He also told CAAWS, “We are proud of the job we do.”24

Steve Dryden, editor at the Hockey News, also defends his paper’s track record on covering female players. The newspaper is one of the most successful weeklies in Canada, with a circulation of approximately 110,000, with 55 percent of sales occurring in the United States.25 The Hockey News focusses almost exclusively on the NHL and its editors do not profess to cover much amateur hockey. When the paper does report on the amateur game, however, editor Dryden maintains it has tried hard to cover women. This is a puzzling assertion, given the scant sprinkling of articles on female teams and players over the years. Citing four profiles of national team players Geraldine Heaney, Stacy Wilson, Vicky Sunohara and Hayley Wickenheiser, Dryden defends his paper’s coverage of the women’s game. “We’ve probably done more than anyone on women’s hockey,” he says. “I’m not saying we’ve done a lot at all, but I’m not making any apologies.”26

There is a prevailing belief among sports journalists and editors that the coverage of women’s sports is improving, but today’s female athletes may well receive less coverage than they did sixty or seventy years ago. In the 1920s and 1930s, Alexandrine Gibb of the Toronto Star, Phyllis Griffiths of the Toronto Telegram, hockey great Bobbie Rosenfeld of the Globe and Myrtle Cook of the Montreal Star all wrote daily women’s sports columns. Other women who reported on major women’s events included Patricia Page of the Edmonton Journal, Lillian “Jimmie” Coo of the Winnipeg Free Press and Ruth Wilson of the Vancouver Sun.27

Today no daily column on women’s sports is published in a Canadian newspaper and most female sports reporters are the only women in their departments. “My sense is that more women are leaving sports journalism than entering it,” says Jane O’Hara, who now teaches newspaper writing in the journalism program at Ryerson University. “There was a blip in the seventies when women were moving into sports, but then a lot of them left [to go to other departments] because they were much more comfortable elsewhere.”28 Even if more women were hired by papers to cover sports, it would be no guarantee that they would even want to write about female athletes. In fact, some say it would be professional suicide to take on women’s sports as a regular assignment. As Mary Ormsby puts it, “I won’t get on the front page if I cover ringette. You want to cover what’s hot.”29 Furthermore, female reporters such as Ormsby resent being pigeonholed as the “girl columnists.” In 1991 Ormsby was asked by her editor to write the weekly women’s sport column, “At Large,” for the sports section. “I was upset and mad and I thought, ‘Oh great, you want to do a women’s column so who are you going to get? The only woman working in the department. Thanks very much,’”30 relays Ormsby. After five years of writing the column she says it still rankles but she continues to cover women, often out of guilt. Indeed, in the early 1990s, Ormsby provided some of the best coverage of the women’s national hockey team in the country. “If I don’t cover [female sports], no one else will,”31 she surmises.

Although many sports reporters and editors acknowledge the limited perspective on sports that prevails in their papers, they are also quick to point out that a lack of support from female readers makes reporting on women even less rewarding. Ormsby says she rarely gets any feedback from her column. “I’m wondering Are you even reading this stuff?”’ she says. “[Women] phone about the Leafs well enough.” CAAWS’s executive director, Marg McGregor, however, contends that women’s silence with regards to sports coverage is in itself an expression of protest—that women are simply skipping over sports because there is nothing there for them.32 Wendy Long of the Vancouver Sun doesn’t agree. She maintains the silence serves only to assure editors that nothing needs to change. “I constantly have women coming up to me and complaining about the lack of coverage of women’s sport, but they’re choosing someone who is already committed to the cause and someone who doesn’t have the power to make the changes,” says Long. “Yet, when I ask them to phone or write a letter to our editor in chief and promotions people, rarely do they take that step.”33 Asked what action women should be taking, Long cites the example of what soccer fans do in Vancouver when they feel the sport isn’t in the newspaper enough. “[The soccer fans] jam the phone lines, write letters and generally make life miserable for us,” reports Long. “To get them off our backs we make sure we print the scores!”34 It is a strategy that Diana Duerkop endorsed in a CAAWS newsletter editorial entitled “Only Ourselves to Blame.” “Canadian women squandered an opportunity they’ll have only once,” wrote Duerkop about women’s failure to capitalize on the October 1994 labour unrest in professional hockey and baseball by flooding newspapers with story ideas about female athletes. Instead, observed Duerkop, “[women] stood by as newspapers published an interminable supply of stories about minutiae that even dyed-in-the-wool sports nuts found nauseating.”35

If women—and men—who are interested in women’s sports are failing the reporters, so are many of the amateur sports organizations, whose task it is to promote their female programs. The Canadian Hockey Association is no exception. At the core of the CHA’s promotion of female hockey is the same “little sister” principle that seems to govern so many of its decisions regarding the development of the female game. Promotion of the women’s game simply has not been a priority in the world of male hockey, a reality that is reflected by the constant inability of the CHA to procure decent television, radio and newspaper coverage for national and world championships.

The general disregard for women’s hockey at the CHA means that the responsibility for the entire women’s program, including media relations, has fallen almost entirely on its sole manager, Glynis Peters, who juggles a host of disparate tasks. Moreover, the gains that have been made in the female game, namely, its inclusion in the larger CHA sponsorship package in 1995 and the national team program leading up to the 1998 Olympics, seem precarious both to national team players and to Peters. Fearing that any critical reporting on female hockey and the national team could jeopardize women’s gains within the CHA, Peters has appeared increasingly reluctant to question inequities within the organization. For instance, in February 1996 Peters defended the CHA requirement that the top fifty-four female players in the country pay a fee of $100 to attend a national team evaluation camp. “Sometimes I have to tell players, ‘I’m sorry all you do is look over your shoulder and see how things are for the guys,’”36 she said. Although as amateur sport funding dries up in Canada more elite athletes are having to pay for some of their training expenses, such a fee is not required from members of the men’s senior national team, who enjoy a full-time salary.

With regard to the CHA promotion of female hockey, a number of editors and reporters complain that they receive little or poor-quality information about the sport’s events. It is a criticism levelled not only at the CHA, but at amateur sports organizations in general. The Toronto Star sports editor, David Perkins, says he received “not one piece of advance information from the CHA” about the 1996 women’s national hockey championship, and was flabbergasted to learn that the CHA had faxed its press releases not to the Star, but to Lois Kalchman, a freelance reporter for the paper, who happened to be away at the time of the event. Consequently, Perkins says, the paper missed covering the story itself, printing instead a short piece from a wire service. The Hockey News, too, complains of the CHA’s ineffectiveness at notifying the paper about its female events. “For example,” says Dryden, “I don’t even know who the PR person is for women’s hockey.”37 He says he also does not know who holds that position at the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association, which represents half the female players in Canada.

While by many accounts the CHA does a poor job of letting the media know about its events, when it does promote the sport, it often makes the classic blunder of billing itself as “the fastest-growing sport” in North America—a claim the CHA has often made regarding the female game. “That’s a guaranteed turn-off,” says Perkins. “It’s just a buzz-word and it’s not possible to believe all the twenty-eight sports that claim this each year.”38

The kind of press releases sent out for the 1996 Pacific Women’s Hockey Championship held in Richmond, BC can pretty much guarantee women’s hockey will be overlooked. Although these press releases do not necessarily reflect the quality of most CHA releases for women’s hockey, it is disturbing that in 1996 such poorly written promotional material is forwarded to the press. The release for the first Team Canada versus Team Japan game reads:

The second game of the night featured Our National Team playing Team Japan. This being the first ever Championship game played in Richmond our National Women’s Team wanted to put on a show and that they did …. The Coaching staff, lead [sic] by Shannon Miller of Calgary had this team very focused going in to this game and not once did they take their opposition lightly, as games can change very quickly. Team Canada out shoot [sic] Team Japan by a large amount of 70 to 8. The skill level is not quite there for our visitors from Japan but they are to be commended as everyone connected with the team were very friendly to everyone and were very pleased to be a part of this major event.

The next opponent for Team Canada is Team China …. To win they must stay focused and have lots of discipline to stay in the hunt for the Championship Trophy….

With press releases like this, one can hardly blame the major newspapers for having failed to print even the perfunctory bottom-corner articles they ran for the 1996 women’s national hockey championships the week before.

Another example of publicity that falls short of its goal occurred in October 1995 at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto. In a move supposedly aimed at drawing attention to a national training camp, the CHA arranged for elite players to sign autographs at the Hall of Fame. Present to receive the public were five national team contenders, including sport celebrity Manon Rhéaume. Rhéaume, who can draw hundreds to autograph signings, sat alongside the other players inside the Hall as confused stragglers trickled by. “Oh, I thought it was the men’s national team!” exclaimed one clearly disappointed woman as she entered the side-room in which the players idled. Her confusion no doubt stemmed from the absence of any signs at the entrance of the Hall and from the lack of prior publicity, save one token last-minute announcement in the Toronto Sun.

The fact that such an unsuccessful publicity event occurred within the chambers of the Hockey Hall of Fame only emphasizes the fact that not one women has been inducted into the Hall. As Bruce Kidd writes: “Halls of Fame play a strategic role in the public remembering and interpretation of sports. Through their annual, often well-publicized selections and inductions, they confer status (and lifetime bragging rights) upon those selected …”39 In 1995, former national women’s team member Heather Ginzel decided to change this and nominated female hockey veteran Shirley Cameron to the Hall. Despite Cameron’s impeccable credentials—she is a former national team member and has been part of twenty consecutive championships as a player and then as coach of the Chimos—simply filling out the nomination form was a challenge. “I looked for someone who would blow them out of the water, but the form is made for men,” says Ginzel. “I had to go through it and doctor it so her whole career could be placed in it.” Furthermore, when Ginzel wrote to the CHA for a letter of endorsement, she was turned down. What the CHA proposed instead was that it could strike a committee that would establish criteria for female players to be nominated to the Hall. Such a committee has not yet been formed, and Cameron’s nomination was rejected by the Hall of Fame.

The lack of proper promotional materials and media coverage of women’s sports is not unique to hockey or the print medium. A study conducted by the Los Angeles Amateur Athletic Foundation in 1990 found that women’s sports comprised only 5 percent of televised sports in the US. Most of the coverage went to gymnastics, figure skating, tennis and golf. Although women receive better coverage during the Olympics, male athletes are still followed much more closely by the media. A Sport Canada study on the CTV coverage of the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer revealed that interviewers overwhelmingly chose male athletes, coaches, and even male persons on the street for comments. Forty-one percent of the events in the Winter Olympics were female and 56 percent male (3 percent were mixed), yet men received 64 percent of the coverage, compared with 26 percent for women (10 percent was devoted to mixed events). Interestingly, the telecasting of men’s hockey was largely responsible for the imbalance; men’s games made up almost half of the coverage of all the male sports.40

For the duration of the 1988 Winter Olympics, Margaret MacNeill, a professor at the School of Physical and Health Education at the University of Toronto, went behind the scenes with the CTV domestic television crew in Calgary to study how (male) hockey was produced. In the late 1980s, rating agencies that measured the size of TV audiences for broadcasters usually gave just the total number that could be expected to tune into the Olympics, without breaking the audience down by gender—something that is now done by the rating agencies. What soon became apparent to MacNeill was that the cameramen geared the coverage to men. “ [The] television crews assumed the audience-of-address they broadcast to was wholly male. Although many Canadian women are fans of hockey and the growth in participation is booming, women are not assumed to be ‘serious’ fans of the game according to the crew, yet they have no market research to substantiate these claims,” writes MacNeill. “When close-ups of female fans … were broadcast … they were constructed as cheerleaders, not fans. The crew’s choice of passive, young feminine-appearing women to fill what they called the ‘beauty shots,’ served to reproduce the notion of hockey as a rugged masculine game.”41 Furthermore, while the European and French Canadian broadcasters chose to leave out much of the violence by switching to commercials, “CTV, on the other hand, broadcast fights in their entirety,” reports MacNeill. “CTV considered fighting to be an ‘essential’ part of the ‘news’ of the game.”42

Although women and men follow the Olympics with near equal interest, men watch televised sports more than twice as much as women do in Canada.43 Indeed, about 70 percent of the viewers of Canada’s sports-only network, The Sports Network (TSN), are men, a percentage that matches the proportion of hours allotted to male sports on the network.44 The circular argument that keeps newspaper editors from giving more print to amateur and women’s sports also keeps network heads from broadcasting them. (This is despite evidence from one survey that 70 percent of sports fans would be equally interested in watching men’s and women’s competitions if they

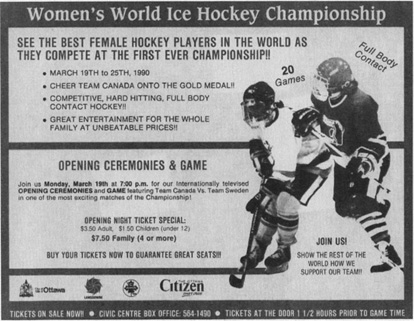

Poster from the first official world championship assures fans of “hard hitting, full body contact hockey.”

were telecast.45) “TSN is seen as male-dominated in terms of audience,” says Rick Brace, vice president of broadcasting at TSN. “We get some criticism [for that].” But Brace goes on to say that the network has no immediate plans to broadcast more women’s sports because it covers events only according to audience demand.46

During the first world hockey championship for women in 1990, TSN broadcast four of the games. However, since then the network has telecast only one other world game: the gold-medal game for the 1994 world championship. Although the commentary improved somewhat in the 1994 game, for both final games the main commentators were men—Michael Landsberg and Howie Meeker in 1990 and Peter Watts in 1994—whose expertise lay in the men’s game, not the women’s. In 1990 Landsberg focussed on the pink theme of the event, a promotion tactic the CHA devised, as discussed in Chapter 1. Although he was sincerely enthusiastic about the women’s game, Howie Meeker felt the need to frequently reassure the audience of the “tough-hitting” style of the game.

From a media perspective the 1990 championship was a smashing success—more than 100 print, radio and TV journalists covered the event, which was attended by more than 20,000 people; the television audience averaged 450,000 for the first three televised games and about 1.5 million for the gold-medal game. However, media coverage dropped off precipitously immediately following the event. In 1992, when the championship was held in Finland, TSN opted not to broadcast any of the games, citing a mid-afternoon time slot and little interest from advertisers as two of the reasons for not covering the event. The network also said it considered the cost of the satellite feed—$40,000—to be too high. “The first year [1990] we covered the Worlds there were a lot of promises from the organizers that didn’t come through,” explains Brace. “The companies [who the CHA said would buy advertising] didn’t come through and we ended up subsidizing the event. We were cautious the second time around.”47 Indeed they were. The caution, however, struck many fans of the female game as excessive, and even the CHA voiced its objection to the absence of coverage in a letter to Brace.48

TSN was also cautious the third time around. For the 1994 world championship, which was held in Lake Placid, New York, the network decided to broadcast the final game only. Although this game took place on a Sunday at 3:00 PM EST, TSN did not televise it until 10:30 PM EST, which meant those intent on watching the historical “three-peat” victory for Canada had to stay up until 1:00 AM. With a time slot like that, ratings hardly stood a chance of improving.

In 1995 TSN renewed a second five-year contract with the CHA to broadcast sixteen amateur hockey games yearly. Women’s hockey was included in the package this time, although TSN says the CHA made no stipulation in the deal that female games must be broadcast annually. Since 1995, TSN has covered one female game each year—the final game of the national championship. Brace says he does not foresee the coverage increasing for at least the next few years. “The game will have to be considered where men and women are at the same playing field,” he says. “The women’s game is different … and the numbers make it harder to sell.”49

“Selling” is absolutely fundamental to the telecasting of sports. Networks operate as businesses, selling viewers to advertisers. The televising of a sport, and hence the sponsorship of it, are critical to a sports growth and survival. Yet only very recently has corporate money—and a very small amount of it—come the way of women’s hockey. From 1982 to 1996 national championships for senior female hockey players have received corporate funding for a total of five annual events. Shoppers Drug Mart gave $15,000 annually for the championship from 1982 to 1984. Rhonda Taylor (then Leeman), the development coordinator for the OWHA during that period, says that in return for sponsoring the national championship, Shoppers Drug Mart required a high-profile press conference; its name on the official championship title, logo and souvenir items; and television coverage. “I look back now and laugh at [the deal],” says Taylor. “They wanted everything under the sun. But we were just so happy and grateful simply to make the event occur.”50 For the 1982 championship, Taylor says that Shoppers Drug Mart even took it upon itself to subsidize its own donation with other donations from Scott Paper Ltd., Planters, Wintario and Air Canada, putting their names on 25,000 flyers it distributed in its stores. The total amount donated, including a small sum from Sport Canada, covered only the costs of ice time, officials and half the players’ travel expenses. CBC’s Wide World of Sports ran selected highlights from the game, Hockey Night in Canada promoted it during an intermission and CFTO, CBLT and Global reported briefly on the event during their news programs.

After sponsoring national championships for three years, Shoppers Drug Mart decided against renewing the agreement. The fanfare of women’s hockey as a “new” sport had blown over and media coverage had quickly dried up. It was not until ten years later that women’s hockey was again to have any private funds channelled into it—this time through the CHA. In July 1995, the women’s national championship and the national team were at last sold as part of a package deal with the men’s national junior team program to Imperial Oil, Air Canada and, in 1996, the Royal Bank. The CHA negotiated with Imperial Oil to be the title sponsor for women’s hockey, which means that since 1995 the women’s national competition has been called the “Esso Women’s National Hockey Championship.”

Although neither the CHA nor Imperial Oil will disclose the total amount of the sponsorship package, the CHA says it allocates approximately $50,000 towards the women’s national championship and the national team.51 The money comes to women’s hockey in the form of direct financial support for participating teams, advertisements for the national championship and national television coverage. TSN, the “official broadcaster” of the CHA, is also considered a sponsor due to its telecasting of CHA games.

Ron Robison, the new senior-vice president of business for the CHA, negotiated the contract with the sponsors. Robison decided to include the women’s program and other products that were considered difficult to sell, such as the tier-two male Junior A championships, as part of the whole amateur package, thus guaranteeing at least some money for these programs. The difficulty in selling female hockey to sponsors, parents and girls lay partly in its “image problem.” “The sport has been historically male, aggressive and violent at times, and we have to work on all those to make it a more attractive sell to all girls,” he explains. “All we want to do is assure parents through vehicles like corporations that the sport can be safe.”52

But trying to distance the female game from the NHL is not without its pitfalls, either. What is circumspectly referred to by marketing executives as “the physicality” of the men’s game is a factor still regarded as crucial to selling hockey. “The problem is that a lot of people have the perception of [women’s hockey] as a poor cousin to the real thing. They see it as a physical sport where a big part of it is banging people into the boards,” says John Dunlop, executive vice-president of the St. Clair Group, the CHA’s marketing company. “It’s a lot easier to sell [a game like] women’s tennis where the emphasis is on finesse. It’s tougher to see women participating in those physical games. It’s not a positive in terms of sales circumstances; it’s a hurdle to overcome.”53 The statement that it is “tougher to see” women participate in physical games assumes that the public is not ready to handle aggressive, powerful images of women. Yet given the paucity and relative newness of such images in both the media and advertisements, it is unlikely that marketing executives or anyone else have a solid grasp of what the public would like to see.

To make matters worse, corporate sponsorship of the women’s game has proven to be a more challenging sell due to the recession of the 1990s, according to Dunlop and his colleagues. Corporations will no longer simply attach their name to an event or product as they might have done in the 1980s; they require an integrated packaging, including television, print, product sampling, promotion and rights affiliation. The more stringent requirements of corporate sponsors will particularly affect women’s hockey. While the sport’s rapid growth is considered a “positive sidebar” by marketers, in terms of public recognition it is a long way away from other amateur hockey properties. Television ratings reflect just how far away it is: eighty-two thousand people watched the final game of the 1996 national championship on TSN. Although this represents an increase of six thousand from the previous year, this number is low in relation to the 146,000 people who watched the male Junior A championship, the Memorial Cup, in 1995.54 Furthermore, because the TSN audience is largely male, advertisers of women’s products are not exactly lining up at the network’s door.

Although younger elite players such as Nancy Drolet of Quebec are becoming more vocal about the need to procure sponsorship, most current and former players, parents and fans have been noticeably silent on the issue. This passivity is particularly troubling given the increasing government cut-backs to all amateur sports. In 1995–96 alone, funding to 121 national sports was slashed by 20 percent and dozens of sports have had their funding eliminated altogether. Athletes are being forced to rely more and more on corporate sponsors. Canadian female athletes would do well to take their cue from their American sisters. Members of the US women’s soccer team—a team that placed first in the 1991 world championship and third in 1995—went on strike in September 1995. They refused to attend their training camp or sign contracts until they were assured they would get a bonus sum of money if they won a gold medal, or a silver or bronze medal.

While sponsorship and media coverage are important ways to help the growth of women’s hockey, retaining the integrity of the athletes will be increasingly difficult with corporate pressure. Female athletes are still marketed in a way that stresses their sexual attractiveness rather than their abilities. It is hardly surprising that most of the female sports that have garnered sponsorship so far are sports such as tennis, gymnastics, golf and figure skating - sports that often feature women in skimpy outfits. Indeed, some female figure skaters earn even more than their male counterparts.

Needless to say, hockey, as a team sport that emphasizes aggression and toughness, does not capitalize on traditional feminine qualities. That has not kept some sponsors from trying, however. The program for the 1982 Shoppers Drug Mart national hockey championship presented the game this way:

For years sports were viewed as predominantly male activities, but the recent surge of interest in physical fitness in women’s health and beauty plans has prompted a greater awareness of the importance of organized women’s sports.

Today many vibrant women experience the excitement and challenge of playing team sports without the once-prevalent “tomboy” image. Terri, a dedicated sports enthusiast, has been playing hockey for years …. [Girls] such as Terri strive for fulfilling social lives, where new friends are often surprised to find that beneath their beauty, poise and femininity, lie enthusiastic and talented hockey players ….

Doug Philpott, the head of Hockey Projects Client Services, who has marketed women’s hockey for the St. Clair Group, talked excitedly about the “really good-looking ladies” now playing and how this would help sell the game. “You wouldn’t even know that a lot of these ladies played hockey if you had to pick them out of a lineup,” he exclaimed in 1996. “And the Finnish team! What a striking team. The women are just gorgeous. They look like runway models.”55 When asked if the attractiveness of players was a factor in marketing male hockey, he laughed: “It’s not an issue at all. We even run guys with no teeth.”56

What lurks just below the surface of the “feminine” marketing angle of female athletes is the attempt to distance women athletes from suspicions of lesbianism. Indeed, as many female hockey players readily acknowledge, the word “feminine” is often a code word for heterosexual. In a society that has defined sport as an activity for boys and men, women who participate in athletics have been regarded as breaking a well-entrenched feminine code of conduct. This view of female athletes is nothing new. Beginning in the 1880s, doctors warned parents and teachers about the “masculinizing effects” of certain sports on girls, claiming athletic involvement would lead to masculine mannerisms, deeper voices and bulky muscles. Sports for girls, the argument went on, would also put in jeopardy their ability to have children and confuse their sexual identity.57 Labels such as “mannish” were applied to women who took sports seriously. Implicit in this designation was a deep suspicion of female athletes’ sexuality. As early as the turn of the century, pressure mounted for women to prove their heterosexuality. By the 1930s sexy or feminine clothing codes were imposed on female athletes by schools, coaches and sports organizations. Short hair was discouraged and women were urged to present their boyfriends to the public. By the 1950s all-girl activities, especially team sports, fell under public scrutiny for fear of the “lesbian threat.” Sports such as tennis, golf, bowling and horseback riding were recommended in their place.58 These themes of concern resound within the field of sports research to this day. “[T]here’s never research on the femininity of ballet dancers or female figure skaters or female synchronized swimmers,” points out sports sociologist Helen Lenskyj, “but there’s a hell of a lot of research about the femininity … or the lack of… [it in] basketball players, and sport administrators and softball players. And so it’s pretty obvious what’s going on.”59

The effects of homophobia and the attempts by sports organizations to hide the lesbian presence on teams have repercussions beyond the theoretical for both athletes and coaches today. Coaches, for instance, have been fired or passed over because of their sexual orientation. In one public case, the head coach of the Canadian women’s volleyball team, Betty Baxter, was suddenly dismissed by the Canadian Volleyball Association in 1982. While no mention was made of her lesbianism when it was explained why she was dismissed, Baxter protested the firing, telling the Toronto Star that, “qualifications had nothing to do with it.”60

Because admitting the presence of lesbians and gays in a particular sport can have such devastating effects on its athletes in terms of sponsorship and media coverage, it is difficult to find athletes who will talk about the issue on the record. Only two former Team Canada members would. “Because we’re becoming a higher profile sport, there’s even more pressure to project a certain image,” says Chimos coach Shirley Cameron. “It’s a kind of a joke amongst players: grow your hair long or you won’t make the national team. It’s a joke because there is that pressure to sell the sport and they may pick players not always just on talent. There’s the image part of it—the being married, having kids sort of thing.”61 Another former national team member, Heather Ginzel, puts it this way: “The CHA thinks that the majority of women are straight, and no one will talk about it,” says Ginzel. “How does that make you a good person or a bad person or good or bad hockey player? There are unfortunately a lot of people who disagree with [lesbianism]. It’s an image thing. ‘We don’t want a bunch of dykes representing our country.’ If they only knew.”62

The monetary consequences of non-feminine females in sports or allowing open lesbians to represent a sport are palpable. Elite women’s teams, no matter how successful they are, have a much harder time procuring sponsorship dollars than women’s individual performance sports do. Yet even within individual sports, the negative repercussions for an athlete who does not play up her heterosexuality are powerful in terms of sponsorship. The example of tennis player and “out” lesbian Martina Navratilova gives some indication of just how costly it can be for lesbians not to hide their sexuality. In 1992, with fifty-four Grand Slam titles, Navratilova had sponsorship contracts worth $2 million. Heterosexual Steffi Graf, on the other hand, had only eleven Grand Slam titles, yet earned three times that amount.63 Jennifer Capriati and Gabriela Sabatini, who at the time had never ranked number one, made as much or more than Navratilova.64

In addition to pressuring teams to present feminine-looking athletes corporations pressure the sports media to stay away from sports that have traditionally been associated with men. Former basketball player and author Mariah Burton Nelson reports that when she worked at Women’s Sports magazine in the 1980s, advertisers threatened to withhold ads if the magazine covered bodybuilding, weight lifting, basketball, softball or other “dykey” sports. The magazine soon changed its name to Women’s Sports and Fitness to downplay female athleticism and included more photos of slim, heterosexually-appealing women in its issues.65

A less visible but just as pernicious effect of homophobia within sports is that it keeps girls and women from joining up in the first place. A number of national team players recall that in their teens they stayed away from hockey, despite their interest in the game, because of rumours that many of the players were gay, and their fear of being seen that way by their peers. “Everybody knows and assumes [you are a lesbian], so you have to be confident of who you are,” says one national team player, who wished to remain anonymous. “With young kids this could make or break the sport. I know some mothers who wouldn’t let daughters play with lesbians … [even though] they know their daughter loves the game.”

Homophobia also has the effect of causing players, both gay and straight, to scrutinize their clothing and behaviour for any hints of masculinity. Many hockey players talk of the need to “clean up” the image of the game by presenting themselves in a “professional manner.” At Female Council meetings with the CAHA, the former Nova Scotia representative Lynn Hacket recalls members were very conscious of trying to counteract the stereotype of female players: “We always wore a skirt, a dress or dress-pants. We always looked like females,” she says, adding, however, that, “I didn’t have a problem with the lesbian presence, but I had a problem with people who told me I didn’t look like a hockey player. I realize now they were saying that I didn’t look like a lesbian.”66

Although almost all female hockey players who play at the elite level complain about being questioned by the press about boyfriends or husbands in what they see as transparent attempts to determine their sexuality, some say lesbian-baiting among players can be just as strong. Melody Davidson, coach and female hockey advocate in Alberta, maintains that some of the baiting comes from the players themselves. “A lot of things that are created are created from within,” she says. “Players always sitting around questioning who’s gay and who’s not. People always assume I’m gay. At times when I first started, it was guilty until proven innocent.”67

In a female sports world that generously rewards traditional feminine qualities and that punishes traditional masculine characteristics, it is no wonder that lesbian athletes are not lining up to reveal their sexual orientation. Yet until this changes, homophobia will remain a powerful tool to intimidate all women in sport. The so-called lesbian issue is, in fact, a gender equity issue. When corporations refuse to sponsor “masculine” female sports, when the media fail to properly report on them and when sports organizations encourage women to hide their sexual identity, all female athletes are affected. What homophobia does in the long run is assure that money and media attention continue to go almost exclusively to men’s sports and to straight-appearing male athletes. This is not to say that homophobia within male sports is any less forceful—indeed, sports have traditionally provided men with an arena in which to prove their masculinity and heterosexuality. The pressure for gay male athletes to hide their sexuality is, therefore, perhaps even more powerful within the realm of men’s sports. As Brian Pronger, a lecturer on sports and ethics at the University of Toronto, observes: “In our culture, male homosexuality is a violation of masculinity, a denigration of the mythic power of men, an ironic subversion that significant numbers of men pursue with great enthusiasm. Because it gnaws at masculinity, it weakens the gender order.”68

While the strong tendency among sponsors and media to emphasize the attractiveness and femininity of female athletes is disturbing, in general this kind of portrayal is decreasing. Editors and journalists alike are becoming more aware that focussing on the appearance rather than the abilities of players is no longer acceptable. “I think that the media generally have improved over the last ten years,” says Marg McGregor of CAAWS, “[and] that we are seeing more stories of the women’s hockey team and [other female athletes]…. But we’re still a long way away from where I think we should be.”69

Glynis Peters of the CHA also thinks journalists are doing a better job at reporting on women. “The quality of coverage has improved dramatically,” she says. “It used to focus on the sensational angle of women actually playing the game, when the first woman would play in the NHL and how they first started to play. Now the media is in general more educated and willing to take women’s hockey at face value.”70 In the early 1990s, reporters began to be more aware of the traditionally overlooked subject of female sports, but they showed their ignorance of history in the frequency with which female athletes were hailed as “pioneers” in the press. Many reporters had only recently discovered the calibre of certain female sports, writing about them as if they were something entirely new, rather than something entirely new only to the reporter. In the case of hockey, the discovery of the women’s game was particularly amusing given that girls and women had been playing it for more than a hundred years. Amusing too—though tiresome—was the apparent fascination on the part of some reporters with the fact that girls and women even want to play hockey. As one reporter acknowledged in a story on Team USA member Cammi Granato, “The burning question [for reporters] is how they [athletes] compete in their chosen sports. For women hockey players, it is still, ‘Why?’”71

When the novelty-approach reporters were not asking, “Why?” they were scrambling to understand the game within the only context they know: men’s hockey. Even today, female players continually lament being compared to men. Indeed, the number of references to national team players Angela James, Geraldine Heaney, France St. Louis and Hayley Wickenheiser as “the Wayne Gretzkys of female hockey” again reflects reporters’ ignorance of the female game rather than their attempt to compliment a player.

“It’s great to get coverage, but not when it assumes all girls want to play with boys and like boys,” says Glynis Peters. “If the media would only phone somebody who knows about the sport when they go to cover it and not just assume that hockey’s hockey and use the same points of reference that they use with male hockey and just apply it to girls.”72 Sue Scherer, a former Team Canada player, agrees. She says that journalists have frequently missed the point. “When journalists wrote about me when I was younger, they would say I love sports, which I do. But then the articles would go on with some reference to growing up with boys being responsible for my success. My success isn’t due to my brothers. It’s due to a lot of hard work and having the guts to do it,”73 she says.

Nobody in women’s hockey better typifies the various ways the media and sponsors have framed female players than Manon Rhéaume, the most famous female hockey player in the world. Rhéaume, a Québécoise from Trois-Rivieres, was the first women in North America to sign a contract with a men’s professional team and to play a game in a professional league. Several months after earning a place as the number-three goalie for the Trois-Rivieres Draveurs of the Quebec major junior league—the highest level of hockey below the NHL—Rhéaume played with the team in a regular-season game in November 1991. Less than a year later, she was asked to try out for the NHL Tampa Bay Lightning by owner Phil Esposito, and played her first period of professional hockey in an exhibition game in September 1992. Soon after, Rhéaume signed a three-year contract with the Atlanta Knights, a minor league team affiliated with the Lightning. In December 1992 she became the first woman to play in a regular-season game in men’s pro hockey and in April played her first full game. Since then Rhéaume has played on a number of professional and semi-professional hockey teams, most recently for the Charlotte Checkers of North Carolina.

Commercial portrayals of Manon Rhéaume (top); celebrating Team Canada’s third gold medal.

With her entry into the pro leagues, Rhéaume found herself suddenly catapulted into stardom. Never before had a female hockey player received so much press attention—or fan adoration. As Rhéaume skated onto the ice wild crowds chanted, “We want the chick! We want the chick!” Within weeks of her first major junior game, Rhéaume received the much-reported offer from Playboy to pose nude for $40,000, a proposal she declined. Soon after the exhibition game with the Lightning, Rhéaume ranked fourth in a survey of Quebec’s favourite athletes and thirteenth in a December 1992 USA Today popularity survey of athletes—ahead of Mario Lemieux. She was also heralded by Time magazine as the seventh wonder of the sports world that year. By the end of her first year in the pro leagues, she had attracted the attention of CNN, ESPN, The Today Show, Good Morning America, Entertainment Tonight and had even appeared on Late Night with David Letterman.

Hundreds of articles have been written on Rhéaume. Many have focussed on what they assumed was the “gimmick” element of her participation in the pro leagues, dismissing her as nothing more than a cheap ploy to sell tickets. Other reporters have vacillated between depicting Rhéaume as a gimmick and hailing her as a great benefactor of women’s hockey. “Women’s hockey has landed a celebrity who has provided the game with an unbelievable opportunity for promotion,”74 wrote Mary Ormsby in 1992. Exactly a year later, Ormsby’s take was different: “This latest girl-goalie promotion smacks of the same masterful media manipulation so beautifully orchestrated by Phil Esposito last fall. He didn’t sell hockey to Floridans… but sold an attractive female goalie instead.”75

Many other articles zeroed in on her physical appearance, completely side-stepping her performance as an athlete. Two of the most glaringly sexist features on Rhéaume were published in the Toronto Star. In one, columnist Rosie DiManno described Rhéaume as “a comely nubile with hazel eyes, a glowing complexion, and a decidedly feminine grace. There is no hint of testosterone in her nature.”76

Constant mention of the offers from Playboy, and later Penthouse, to pose nude also surfaced in articles on the player, once again drawing attention away from Rhéaume as an athlete and onto her image as a sex object. The use of this angle to cover her reveals a great discomfort on the part of the media at the prospect of a woman succeeding in a traditionally male sport. Rhéaume soon found herself in the position of having to defend her choice and field endless asinine questions about whether or not she broke a fingernail while in net, or spit on the bench like most hockey players, or how her boyfriend handled her hockey career.77 In her book, Manon: Alone in Front of the Net, even she feels obliged to reassure her fans of her femininity. In one passage she writes:

I don’t exactly eat nails for breakfast, but I can bench-press a few pounds and I do a few hundred sit-ups a week. I have no plans to compete for the Miss Muscles title—far from it. I work out to improve my cardiovascular system and my muscular endurance. I don’t want big muscles, just what I need to be able to stay in the shape a good goalie needs to be in. I try to keep a feminine figure and I have no desire to “bulk up” with extra weight.78

Yet even those reporters who claimed to endorse Rhéaume the athlete did so entirely within the context of the male sports world. Not only did many expose their ignorance of the female game by referring to her as the best female goaltender in the world, which she was not, but they also lauded her for successfully fitting into the men’s jock culture, as if this were an accomplishment of the highest order. In a profile on Rhéaume in Saturday Night magazine, journalist Brian Preston relays a conversation about hockey between Rhéaume and another reporter, and concludes, “You can’t help but like her. She’s twenty-two, and even in a second language knows how to banter with men.”79 As sports columnist Michael Farber observes, “The subliminal message of Rhéaume’s triumph is unsettling: To be successful, women have to be validated in a man’s world. In men’s teams. In men’s terms.”80

Of course, what is missing from 90 percent of the press stories on Rhéaume is context. The real reason Rhéaume jumped at the chance to play in the pro leagues was neither to champion the cause of female hockey players nor to become rich and famous: she did it simply because it was the chance of a lifetime to receive professional training and ice time she would never have received playing on a women’s team. As the Globe and Mail columnist Mary Jollimore writes, “How many male hockey players with such limited experience were invited to the Tampa Bay training camp or that of any other NHL team? None. But consider this. It’s not exactly Rhéaume’s fault she’s had limited experience …. Because she’s a woman she hasn’t had the same opportunity as her male counterparts.”81

Rhéaume herself partly addresses the opportunity gap in her book, recounting the harassment and resistance to her participation in hockey she withstood growing up. Rhéaume was fortunate in having a very supportive father who actively ensured she was given the same chance as her brothers. “Every time I attended a hockey camp, Pierre [her father] insisted that the coach test me under the same conditions as the other goal-tenders,” Rhéaume recounts. “He made sure that the duties were shared half-and-half with the other goalie. In this way, no one could say, ‘Yes, but she was in net against a weaker team….’ He didn’t want to leave any room for doubt.”82 Pierre, however, could assure equal treatment of his daughter only up until a point. When Rhéaume reached the Midget level age at sixteen, pressure intensified for her to leave the game. Although a scout for a Midget AAA team put her on his draft list, when he discovered she was a girl, he scratched out her name. The only team that agreed to let her play was a Midget CC team—one step above what Rhéaume refers to as a “fun league.”83 After a year on the team, Rhéaume quit hockey. She picked it up a year later when she briefly played for the female Quebec team of Jofa-Titan. Attending games and practices, however, involved long hours of commuting and late-night time slots. The chance to play on a men’s team, therefore, was a dream come true: not only was she coached by professionals, supplied with the best equipment and the recipient of excellent ice time, but she was also well paid and amply rewarded through sponsors, poster sales, autograph signings and speaking engagements. The fact that she rarely played in games was a minor irritation in light of the exceptional practice time she has had, and what she would have had to put up with had she switched to women’s hockey.

Whether journalists hone in on the attractiveness of Rhéaume or focus on the publicity aspect of her rise, articles about her invariably trumpet the player as “making history,” “breaking the gender barrier,” as a sport “pioneer” or the inevitable “ice-breaker.” The implication in all of these labels is that it is only a matter of time before other women rush through the gap in men’s professional hockey she has created. Yet as players and supporters of the female game know all too well, Rhéaume is the exception both in terms of her hetero-sexual appeal and the position she plays. For goaltenders, physical strength and size are less important than they are for other players and gender differences are fairly minimal. This explains why the only other women to play on men’s semi-pro teams have been goalies. As sports sociologist Nancy Theberge writes,

It is significant that in the media constructions of Rhéaume’s experience, little attention is given to an aspect of her biography that people in the sport understand to be central to her story. The result of this inattention is that Rhéaume is constructed as the female athletic version of “everyman,” when in reality by virtue of the position she plays, she is in fact rather unique.84

The irony that the most famous female hockey player came to public awareness by playing with men is not lost on female players. While many journalists and admirers of Rhéaume insist that she has done much for the women’s game, others contend that Rhéaume has brought recognition to herself alone—albeit reluctantly—and not to the women’s game. Interested in how Rhéaume was perceived outside the standard male realm, Theberge interviewed two groups of female hockey players, one of girls between fourteen and seventeen years old and the other of elite players between sixteen and thirty-four. Theberge reports that most of the younger players found Rhéaume to be a positive force, commenting that she brought publicity to sport and proved that women can play hockey. As one young American player (not in Theberge’s study) wrote in Newsday, in defence of Rhéaume,

A girl has to earn the respect that male players give each other automatically. When the goaltender is female, there’s always a guy on the other team who winds up and fires a screamer at her head to prove he is too much of a man to be playing around with girls …. Manon Rhéaume [and other semi-pro female goal-tenders] encourage the hundreds of girls who are working hard outside the spotlight. Thriving throughout the stages of boys’ hockey, they have proven their skill and ability again and again.85

While this young player describes what many like her may feel about Rhéaume, the older players Theberge interviewed maintain that the emphasis on a woman’s success in men’s hockey has detracted from the appreciation and awareness of women’s hockey. Theberge reports that none of the women expressed resentment towards Rhéaume personally and few denied that they would take the chance to play in the pro leagues if offered it. Yet many elite female players do resent the fact that Rhéaume was not the best female goalie in North America when she was selected for the pro leagues. “At first it bothered me because, [I felt like,] ‘Who are you? I don’t know anything about you,’” says national team member Angela James. “And I know a lot more people who should be in there ahead of her like [goalies] Cathy [Phillips] or Kelly Dyer.”86 Former national team goaltender Phillips, no longer able to compete after a tumour was removed from her brain in 1990, goes even further. “She hurt women’s hockey in my eyes,” says Phillips. “I would have thought she would have been fantastic … [and] a lot of people who don’t even know women play hockey would think she was the best. Unfortunately, there are a lot of female goaltenders who are better than she is to this day, although Manon has improved dramatically.”87 Twenty-year female hockey veteran Shirley Cameron concurs: “There are so many women who go through female leagues and then she plays one game and gets all the exposure in the world. It’s a real sore spot for many female players.”88

The resentment players such as Cameron express towards the media for celebrating one female player in a male league while ignoring the many others who have played for years on female teams in understandable. Despite the efforts of the game’s promoters, women’s hockey is still measured against the male game, and in the eyes of the media and sponsors, has not fared well in the comparison. Sport has rapidly been taken over by the entertainment businesses—indeed, at the professional level it is now impossible to distinguish where show business ends and sport begins. Given the priorities of corporations and the dominant culture of professional male sports, the female game has stood almost no chance of being appreciated for its own merits and achievements. The “masculine” image of the game and the general ignorance of its history and players have left little room for promotional manoeuvring.

Yet until fans, supporters and the athletes themselves join forces and demand the same appreciation for women’s accomplishments—both in terms of sponsorship and media coverage—the situation is unlikely to change. Female hockey players have been silent far too long about their treatment in the media, and grateful for far too little in terms of funding. Collective action is essential. Those who want to see women’s hockey in the media need to start phoning broadcasters, writing newspapers, lobbying corporations and the CHA themselves for more support. It is time to challenge the reign of professional male sports, especially given the inequities that persist within the sports world, the continued glorification of men’s prowess and the undermining of women’s. Only if women join forces off ice will their power on ice at last be celebrated.

Fans of the women’s game cheer on Team Canada at the 1994 world championship.