THE MCCALLION WORLD CUP sits in the North American zone of the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, a noble but abandoned symbol of the birth of women’s elite international hockey. It resembles a short Stanley Cup, and weighs about thirty-five pounds. The inscription on the cup reads “McCallion World Cup/Donated by the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association.” Hazel McCallion is the mayor of Mississauga and a staunch supporter of female hockey. She played in the Gaspé, Quebec, in the late 1930s, and joined the Montreal Women’s Hockey League in 1942, where she is known as the first woman ever paid to play hockey: she received five dollars a game.

A more telling keepsake from the first world tournament is a battered hockey stick, signed by all the members of the Hamilton Golden Hawks, the team that represented Canada in the first world tournament in 1987. The stick symbolizes both the harsh struggle women have endured simply to play Canada’s national sport, and the indomitable spirit that kept them going when the odds were against them. Along with the McCallion World Cup, it stands as one of the few public reminders of the tournament that jump-started women’s hockey on the road to world competition and ultimately to the Olympics. Just as important, the first world tournament ushered in Team Canada, a long-awaited breed of heroes for the women’s game.

The idea of a women’s world championship took root in 1985, when Fran Rider, then president of the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association (OWHA), invited teams from Europe, North America and Asia to participate in Brampton’s Dominion Ladies Hockey Tournament, the oldest and largest women’s hockey tournament in the world. Two European countries, West Germany and Holland, joined two American teams to play the host Canadian teams from Ontario and Quebec. This modest undertaking prompted the first discussions with representatives of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), the governing body for amateur hockey internationally, about the possibility of a world championship in 1987.

Rider made valuable contacts in the 1985 tournament and spent the next two years writing to hockey officials as far away as China and Australia to invite them to compete in a world championship. The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA), which was responsible for the formation of Canada’s national women’s team, resisted Rider’s initiative claiming that it was too soon for international competition in women’s hockey. There were already too many issues to address at the national level, the CAHA argued, such as the development of coaching, refereeing and minor hockey—issues that were still being ignored as far as the women’s hockey community was concerned.

The CAHA had only begun to contemplate the idea of women’s hockey in the late 1970s, and was still unaware of the distinctive characteristics of the female game, such as the emphasis on finesse and the absence of bodychecking. But for female players and those who were committed to advancing the game, the time for patient waiting was over. Women’s hockey needed more than one national championship, it needed world competition, a catalyst that would not only boost the profile of women’s hockey at many levels (including within the CAHA) but that would finally showcase the stars of the game, introducing these elite athletes to players and hockey fans across the country. As well, a world championship would reward the most talented players with the thrill of international competition and the chance to represent their country—to compete for Canada, as male players had been doing since 1951. A national team match-up could also garner new fans and enthusiastic volunteers and, in the perfect scenario, generous sponsors and supportive media. For fans, organizers and parents, the event would give credibility to a game that many people thought women should not even be playing.

For the OWHA, the time had come to take matters into its own hands. After much lobbying, including a letter of support sent from Brent Ladds, president of the Ontario Hockey Association (one of the provincial governing hockey organizations), the CAHA finally consented to the international competition on the condition that it be called a “world tournament,” as opposed to a “sanctioned world championship.” This endorsement, in the CAHA’s view, implied no obligation on its part to supply funds or administrative support, which it declined to do even though it had already set a financial precedent with male hockey when it launched the first men’s world junior tournament in 1974. For the men’s event the CAHA had paid the air-fare and domestic expenses for all the teams in order to ensure participation, and persuaded the IIHF to launch a world junior championship. The IIHF also refused to sanction this first women’s competition or provide financial assistance. Instead, it simply said it would encourage its members to attend. Nonetheless, the IIHF used the world tournament to judge both the calibre of women’s hockey and to assess the potential for an “official” world championship, which it would consider sanctioning in the future.

Because of the lack of financial and administrative support from the CAHA, a team of rookie volunteers from the OWHA ended up staging this first world competition. Hazel McCallion headed the committee as honorary chairperson and lassoed several corporate sponsors. The Ontario and federal governments issued grants totalling $25,000. The budget for the tournament climbed to $250,000 but without national or international assistance the OWHA fell short by $60,000. To reduce expenses, each team—including Canada—had to foot the bill for its own accommodation and travel. The British and Australian teams were forced to drop out, as were a number of key players from other teams when their hockey federations refused to finance them and they were unable to raise enough private money to cover expenses. Even the games suffered from the financial constraints: they were limited to three fifteen-minute periods to reduce ice time costs.

The Hamilton Golden Hawks, winners of the national championship that year, won the “Team Canada” designation more or less by default, since the OWHA had neither the authority nor the funds to organize a selection camp to choose a real national team. However the tournament rules did allow the Golden Hawks to make themselves look more “national” by bolstering the lineup with players from other teams across the country. Two of those selected were Shirley Cameron, a thirty-five-year-old veteran forward from the Edmonton Chimos, and France St. Louis, the leading scorer from the Montreal Carletons, also an experienced player. Ontario’s powerful scoring ace Angela James had been recruited by the Golden Hawks for the national championship earlier in the year but for this tournament she returned to her club, the Mississauga Warriors, which acted as the host Ontario team. Sweden, Japan, Holland, Switzerland and the US managed to pull together teams that agreed to pay their own expenses. China, Britain, Norway, Australia and West Germany sent observers.

Unlike the other countries, West Germany did not absent itself from the tournament for financial reasons. The tournament rule prohibiting bodychecking was the stumbling-block that prevented its participation. The country refused to send its team, claiming hockey without bodychecking was not “normal hockey.”1 Although Ontario had been playing with bodychecking up until that time, the rule was changed at the national championship in 1986 because of the vast disparity in ages and skills of players. Several provinces, including Quebec and British Columbia, had eliminated it from all divisions. Top senior female players were not paid to play in women’s hockey and therefore could not risk injuries that might result in unpaid time away from work. Astute OWHA officials decided to disallow bodychecking in the tournament because of the immense differences in skating and checking skills, especially between Canada and the European countries. No one wanted broken bones to be the legacy of this first world event. Despite the controversy and budget problems, this was a world event, and official or not, the players were ecstatic. For parents, friends and supporters of the women’s game, it marked the long overdue recognition of a game that was close to one hundred years old. For high-flying twenty-three-year-old forward Angela James, considered one of the best female hockey players in Canada, this world tournament was the first chance to see just how good she could be.

For James, the youngest of five children raised by a single mother, these opportunities did not come often. James’s family stands in stark contrast to society’s conventional model. Defying the social norms of the day, James’s white mother, Donna Barato, bore three white and two mixed-race children, each child with a different absentee father. Leo James, Angela’s black father, spent much of his time at his nightclub in Mississauga. Although James grew up with two brothers and two sisters in her family, according to James, thanks to her father, she also has “other brothers and sisters all over the place.”2

Barato was a loving mother, fiercely determined to raise her children on her own. She even found time to “adopt” a troubled friend of Angelas for several years. Mother and daughter share a deep affection. Protective and passionately loyal, James declares her mother is the key person in her life. “My mom is my influence for everything. She’s been there for me all my life,” says James. “She went to as many national [championships] as possible. She still goes to all my league games. If I don’t pick her up she gets mad.”3 Her mother’s support was critical for a mixed-race child growing up in a tough neighbourhood. When James was six years old, Barato found her daughter vigorously scrubbing her arm in the tub one night. James explained, “I’m trying to get the dirt off. They told me I was dirty.” “Who?” asked her mother. “The kids at school,” answered Angela.4

James remembers a happy family life. Being the youngest, she was spoiled and somewhat undisciplined; her involvement in sports was the one thing in her life that provided her with structure and discipline. “Sport was my way of getting out of a ghetto really, getting out of Ontario Housing,” says James. “I grew up in the parks. There was nothing to do, there weren’t outings,” remembers James. “Every day in the wintertime you went to the outdoor arena and you played hockey. If you didn’t do that you weren’t in with the crowd and you had no friends. That’s also what I loved to do. [The arena] was right next to my school so I could always see it. You ran home, got your skates and went down there.”5

Donna Barato settles into the couch of her four bedroom townhouse in North Toronto (she, a friend and Angela are coowners of the dwelling.) She lights a cigarette in a jam-packed living room while a five-year-old sits watching TV on the floor. She shares the house with a family of four and the son of another friend, who lives in the basement. Just turned sixty, Barato complains good-naturedly about working two jobs at her age. Plump and easy-going, she points with pride to a collage of photos of “my Angela” atop a glass bookcase; she brags about her daughter walking at nine months and about her natural athletic ability in track, basketball, and volleyball. But hockey was Angelas passion. When she was nine she had her appendix removed, and although normal recuperation time was six weeks, James didn’t want to miss the playoffs, and to her doctors amazement was back on the ice in two and a half weeks.

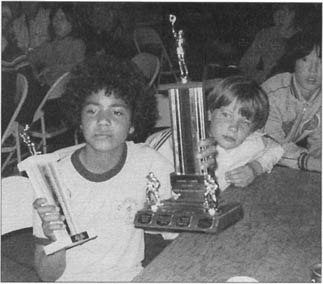

When she was seven, after several years of playing street hockey and shinny on outdoor rinks with neighbourhood kids, James joined a boys’ hockey team. Before long she had won the

Angela James, age 8, receiving high scorer and MVP trophy at Flemingdon Park Boys House League Hockey banquet, North York, Ontario, 1973.

high-scorer award, much to the annoyance of some teammates and a few parents. “The boys weren’t too excited about that. They loved it when we won the games, but not when they didn’t win the awards.”6 In a fine example of the gender politics of sport, the boys’ league refused to allow James to return the next year, insisting that she play on a girl’s team.

Female hockey welcomed James with open arms. By age fifteen she had advanced to Senior A hockey, the highest level for female players at that time. She went from being a scrawny fifteen-year-old to a 160 lb.(72.5 kg) freight train that few people could stop. Fuelled with an outsider’s desire to prove herself and the drive of a teenager competing against senior players, James became known for both her scoring skills and her intimidating physical presence. Some players were afraid to step on the ice against her and over the years, she sent more than a few people to the hospital. While playing in the Central Ontario Women’s Hockey League, she won the high scoring award in 1987 and would go on to dominate the league winning the award for the next seven years.

James also overpowered many of the players in the Ontario College Athletic Association (OCAA) league from 1982 until 1985, capturing all-star-defence and high-scoring honours three years in a row. Part of James’s sports history is enshrined in a glass case at Ontario’s Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology where her number 8 hockey sweater hangs on the wall. The college retired James’s sweater in 1984 and 1985, when she broke five Ontario College Athletic Association records.

Relaxed and joking in a black T-shirt and jeans, James leans back in her chair in her office at Seneca College where she coordinates intramural athletics. She is as informal as her nickname, AJ. Despite the devilish twinkle in her eye, she grows instantly serious when she speaks of those who have given her guidance, and points to former Seneca coach Lee Trempe as an especially vital influence. “She was able to discipline me,” James recalls. “I didn’t have a father figure in my life. She was just doing her job, but at that time she was probably a figure that I needed in my life more than she realized.” In 1985 Coach Trempe railed against the lowly status of women’s hockey and the lack of opportunity for stars like James. “You won’t find a better player anywhere in women’s hockey,” says Trempe. “If she were a man there would be no stopping her, but she’ll never find competition good enough for her.”7

Two years later, thanks to the OWHA, James at last got a chance to test herself against other world-calibre athletes. She and her teammates at the first world tournament faced six other teams in a round-robin format. The winners of the two semifinals played in the gold medal final. In the first round Team Canada easily swept the three European teams, overpowering Switzerland 10–0, Sweden 8–2 and Holland 19–0. Japan was thrashed 11–0 by the larger and swifter Canadians. Even James’s Team Ontario fared no better, falling 5–0 to Team Canada.

The first real competition came from the US, which played a tight, defensive game and managed to severely limit Team Canada’s scoring punch until late in the game. Canada’s Margot Verlaan, known among her peers as the best read-and-react player in women’s hockey, had injured her knee earlier in the tournament. Refusing to let a bad knee stop her when a moment she had long waited for was so close, she pleaded with Coach Dave McMaster to let her play with a knee brace. “I used to tell my mom I wanted to play internationally and she told me I couldn’t do it in hockey. She told me I would have to go into gymnastics. But here I am,” she later told a reporter triumphantly.8 Verlaan scored the winning goal in Canada’s 2–1 f victory over the US. The stage was set for an all-Canadian final when Team Ontario beat Team US 5–2 in the semifinal match.

The all-Canadian gold-medal game was a fierce contest. A disciplined Team Canada patiently built its lead, scoring one goal in the first period and another in the second. As the minutes of the final period ticked away, Team Canada popped in two more goals, finally wearing down Team Ontario’s offensive might, to win 4–0. One of the key players of the tournament, goaltender Cathy Phillips, earned the shutout by making sensational stops, including a diving save on a breakaway by her friend Angela James. Phillips was named best goaltender, thanks to her acrobatic moves and lightning reflexes.

Almost a hundred years after women first took to the ice, Team Canada proudly claimed its first gold medal. This marked its debut in the history-making world competition. Media attention was paltry however, with many of the sports-writers unable to get over their astonishment that women could actually play the game at all. But the OWHA was deter-mined to keep the momentum going. After the tournament it asked each country to file a report with the IIHF. After discussions with its members, the IIHF would decide whether to sanction an official world championship. The Ontario association continued to lobby the IIHF in the face of both national and international apathy. The march towards the ultimate goal, the Olympics, had begun.

Glynis Peters, current manager of women’s hockey for the CHA, readily acknowledges the importance of the OWHA contribution. “I realize how enormous it was for the OWHA to do [the 1987 world tournament] single-handedly … with limited financial [and] administrative resources that were purely volunteer. It was a phenomenal accomplishment because it was the last time that only women and the men involved in women’s hockey organized an event of such scope.”9

Despite the work that went into the tournament, some members of the CAHA simply treated it as a non-event. They were embarrassed that a provincial association had led the international drive for women’s hockey, and hence preferred to downplay the event. “There was no admission by the CAHA that 1987 existed,” said Toronto Star reporter Lois Kalchman. “It’s not that there was resistance to it, it just didn’t exist. At the press conference for the first world championship in 1990, I sat down with France St. Louis and I said to France, ‘Well, isn’t it wonderful you’ve been in the 1987 world tournament and the 1990 world championship.’ She said, ‘We’re not supposed to talk about 1987.’”10

If the CAHA had conflicting views regarding the 1987 tournament, it could no longer turn a blind eye, in the following two years, to the world-wide momentum building for women’s hockey. In April 1989, the IIHF’s president, Gunther Sabetski, hosted the first Women’s European Championship in West Germany. The OWHA’s Fran Rider was invited by Sabetski to attend the event to discuss a future sanctioned world championship. The IIHF proposed that the top five teams from the European championship, along with Canada, the US and an Asian team would play in two pools for the first official world championship which was planned for 1990. The only significant rule changes from the 1987 tournament consisted of lengthening the games to three twenty-minute stop-time periods and permitting bodychecking. The latter allowance was due to considerable pressure from the European countries, despite vehement objections from the CAHA, who now understood the skills gap between Europe and North American teams and did not want unnecessary injuries to mar the sanctioned event. At further meetings with the IIHF, the CAHA offered to host the championship in part because Canada was an acknowledged leader in hockey, but also because few other countries had expressed any serious interest in hosting the event. Moreover, the CAHA realized that it was time to take a leadership role in women’s hockey internationally or risk losing credibility within the IIHF; and they were also embarrassed by the possibility of the OWHA taking control of this aspect of the game.

Not surprisingly, the CAHA’s involvement in the 1990 championship revealed its conspicuous ignorance of the female game. This became all too evident in the way it bungled the selection of the first national team. The CAHA announced the first fourteen players to make the team at a press conference at the Hot Stove Lounge in Maple Leaf Gardens, on January 18, 1990. Dave McMaster, a long-time advocate of women’s hockey and coach for thirteen years for the University of Toronto Lady Blues, was chosen head coach, along with assistant coaches Lucie Valois (Female Council representative from Quebec) and Rick Polutnik (technical director for the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association).

Unbelievably, after dominating women’s hockey for almost ten years, Angela James did not make the list of the first fourteen national team players. It seemed impossible. Coach McMaster told James that she didn’t have a good training camp, but because of her reputation, they would surely take a second look at her at another camp just before the world championship. “My skills didn’t change in the next few weeks. I thought it was bullshit,” recalled James angrily. “It’s my sport and I wasn’t going to kiss ass.” James’s attitude may have played a part in her failure to make the first cut. She was a street-smart kid with a fierce loyalty to her sport, but she had no experience with CAHA politics and no interest in hiding her frustration about the unorthodox selection process. Privately, however, James was devastated. Her mother says it was the first time she ever saw Angela cry.

The CAHA named five more players to the team in mid-February. One month later, the final roster was announced in a press release. Although speculation about the unusually drawn-out selection process ran high, no official reason was proffered. Rumours circulated that some of the final five, including Angela James, were selected late to punish them for their “bad attitude.” Players such as James, Stacy Wilson and Geraldine Heaney, who would become the backbone of future national teams, endured this humiliating and disorganized selection process.

Part of the problem with the selection procedure lay in the CAHA’s lack of interest in women’s hockey. Prior to the discussions for the 1990 championship, the CAHA expressed no interest in considering elite world competition for women’s hockey. Nationally, it had mustered only enough energy and funds to organize one national championship in 1982. Elite female hockey was an incomprehensible leap of the imagination for the male hockey world; indeed it was a leap for most of society. Consequently, no scouting records or coaching pool existed and decisions regarding player selection involved more politics than playmaking skills. The CAHA chose team members based on a six-day selection camp with feedback from coaches and evaluators, many of whom were unfamiliar with the players. Although skilled in their own right, some players with high-profile brothers were chosen for their added appeal to the media, who were familiar only with the men’s game.

The CAHA’s ignorance regarding women’s hockey also translated into a lack of confidence in promoting a women’s world championship. Never having seen most of these talented women play, the CAHA made novelty the central selling point of the championship. Silly gimmicks took over; the CAHA director of operations, Pat Reid, told one reporter that most potential spectators would be attracted by the tournaments curiosity value. “We don’t want to make this out to be something like mud wrestling,” he said, “but let’s face it, the novelty factor will be important.”11

As previously mentioned, in its quest for novelty the CAHA even went so far as outfit the players in pink. Apparently oblivious to the sexist stereotyping, Reid justified the pink uniforms with white pants as a way of adding “appeal” to the game. He seemed to regard women’s hockey as more of a fashion show than a sport. “This is the first time that women’s hockey is going to get national exposure,” Reid told the press, “and I think people are going to think this is a lot more attractive.”12

Had Reid asked Fran Rider, then director of the Female Council for the CAHA and the woman who had spearheaded the first world tournament less than three years earlier, he might have rethought his choice of uniform colour. “If they were manufactured in pink because the players are women, we find that offensive,” Rider stated, summing up tersely what many women’s hockey advocates felt.13 Although Reid’s pink decision did generate copy, it was hardly the sort that brought the kind of respect or attention for female athletes that players and fans desired.

Some reporters took their cue from the CAHA and happily focussed on the sex appeal aspect. Others were highly critical of the colour choice and wrote about it. “Is Canada’s pink and white national women’s hockey team in town for the world championship a dazzling statement of cool high fashion for the future or an example of a degrading stereotype of the past?” wrote Earl McRae of the Ottawa Citizen. “Personally, I love pink and wear it, but I am left with one, nagging question: Would Canada’s national men’s team be happy to wear hot pink and white?”14 The Ottawa Suns sports editor Jane O’Hara was more to the point in her headline, which read: “Sorry Girls, Pink Stinks.”15

Walter Bush, the president of USA Hockey and chairman of the IIHF women’s committee, explained that Tackla, the Finnish company that made the pink-and-white uniforms paid the IIHF $250,000 for the rights to outfit the eight teams at this first world championship. Ironically, had Tackla paid minimal attention to the growing popularity of the sport, its participation in the event would have proven far more profitable.

Tackla brought only $23,000 worth of products to Ottawa to sell during the course of the championship. They sold out in one night. If the pink uniforms weren’t bad enough, the CAHA added to the buffoonery by offering one hundred “beauty makeovers” as part of the draw prizes to promote the semifinal game between Canada and Finland. As for the players, they remained understandably reticent about the promotional schemes. This was the first official world championship and no player was going to protest the decision of a sponsor or the CAHA if she planned to continue playing the game at that level. In the privacy of the team’s dressing room, Angela James described the attitudes towards the uniforms. “The pink jerseys were a bit of a gimmick. The girls said if that’s what it’s going to take to get the fans out, fine. We’ll show them on the ice.”16

Despite the previous lack of recognition, the 1990 world championship garnered international attention for the first time. New fans, the media and even the CAHA were surprised to witness skilled and intelligent hockey played superbly. The gold-medal game held the same excitement as a Stanley Cup for the fans and players. Team Canada rallied from a 2–0 deficit to thwart Team USA 5–2. France St. Louis, her voice still raspy from a stick to the throat earlier in the tournament, topped off her comeback with two goals and two assists in two games. Angela James was named to the all-star team along with Dawn McGuire, who was also chosen Most Valuable Player of the gold-medal game. Canada’s goalie, Cathy Phillips, was voted the tournament’s MVP. Captain Sue Scherer summed up the importance of the championship for female hockey: “We wanted to give young girls playing hockey something to strive for and I think we did just that.”17

Player registration and national team awareness soared after the 1990 world championship. Team Canada set the standard for elite female hockey. Players for the next world event now had to be conditioned like never before—hockey-smart with exceptional defensive and offensive skills. Bob Nicholson, the new director of operations for the CAHA indicated that the time had come to give the women’s national team equal treatment with the men’s junior national team, which meant equipping it for competiton with a similar support squad, including a sports psychologist, the usual motivational T-shirts and office team sweaters. He also outfitted the 1992 team in red and white, the regular national team colours.

For the 1992 world championship, gifted players started to emerge from several provinces. Representation on the national team from Quebec doubled from four to eight players—an indication that both the national and provincial hockey associations had improved their selection process. Newcomers such as eighteen-year-old Nancy Drolet and twenty-six-year-old Danielle Goyette would both figure prominently in the scoring and add more firepower to this already imposing squad. Quebec forwards France St. Louis and France Montour, and defence Diane Michaud also returned. Back again from 1990 for Ontario were Angela James, Margot Verlaan, Heather Ginzel, Sue Scherer, Geraldine Heaney, Laura Schuler and Dawn McGuire. Andria Hunter, a Canadian attending the University of New Hampshire; Karen Nystrom, the lanky speedster from Scarborough, Ontario; and Natalie Rivard, a defensive workhorse from Ottawa, were new to the team. New Brunswick’s hard-working defensive forward, Stacy Wilson, and Alberta’s crafty defence Judy Diduck, both 1990 national team veterans, completed the 1992 roster.18 Goaltender Marie-Claude Roy returned to the roster. Relatively new to women’s hockey but making headlines everywhere was Team Canada’s newest goaltender, Manon Rhéaume from Lac Beauport, Quebec, famous for being the first woman to play seventeen minutes on a Quebec major Junior A male hockey team. The CAHA’s selection of Rhéaume to the Team Canada roster remained controversial. She was not experienced with the women’s game nor was she one of its leading goal tenders. Many observers in the women’s hockey community maintained that Rhéaume’s selection to the national team had more to do with her media profile than her goaltending skills. Two new assistant coaches joined Team Canada: Pierre Charette, a coach with a girls’ high school hockey team in Laval, Quebec; and Shannon Miller, a police officer from Calgary. Head coach Rick Polutnik, who had been the assistant coach from the 1990 championship, emphasized “speed, speed and more speed” in practices.19 On the larger international rink, velocity was crucial in forcing the competition to make quick and (it was hoped) rash decisions.

Canada’s competition was also determined to improve its standings and the results were evident in Tampere, Finland, in 1992. (The IIHF decided to hold biennial world championships to allow countries more time to develop their women’s hockey program.) In two years the talent had improved dramatically on every team and the scores reflected the increased emphasis on defence. In 1990 Canada had outscored the competition 68–8. In 1992 that number dropped by almost half to 38–3.

For the 1992 event, the IIHF had decided to ban body-checking in the world championship since the disparity in skills among most of the European and Asian teams had not changed. Fearing complaints or lawsuits from parents, the IIHF also wished to avoid repeating the excessive number of injuries in the 1990 world championship. Despite the absence of bodychecking and the improvement in their opponents’ skills, Canada overwhelmed the other teams in every category. Team Canada swamped China and Denmark, the two new entries in their A Group. China, the brash Asian entry, fell 8–0. New to the championship, China complained that no one had informed them that bodychecking was not permitted. And even though Denmark was one of the top five European teams, Canada overpowered the Danes 10–0. Team Canada fired seventy-three shots on beleaguered goalie Leni Rasmussen, while Canada’s Manon Rhéaume faced a mere four shots.

It soon became apparent that Canada’s only real competition remained the US and Finland, with Sweden closing in quickly. Sweden lost to Canada only 6–1 versus a fourteen-goal gap in 1990. The other countries languished well below these top four. In Group B, Finland was the only real competition for the American team. The US overpowered Norway 9–1, embarrassed Switzerland 17–0 but only managed to outscore the fleet-footed Finns by two goals winning 5–3. Canada’s three top lines overwhelmed the weary Finns in the semifinal, beating them 6–2. In the gold-medal game, Team Canada thrashed the US 8–0 with a faster, more aggressive players whose forechecking and speed overpowered the Americans. The Canadian goal-scorers included familiar names such as Angela James, who scored two goals, along with Margot Verlaan and newcomer Andria Hunter, who had one goal apiece. Three goals from Sherbrooke’s Nancy Drolet helped to launch her as one of Quebec’s talented new players. Danielle Goyette from St. Foy, Quebec, who weighed in as Canada’s scoring leader for the tournament, also added a goal.

Canadian players dominated the all-star team once again. Manon Rhéaume joined veterans Angela James and Geraldine Heaney along with the US’s Ellen Weinberg on defence, and scoring whiz Cammi Granato on right wing. Canada’s newest national squad was now undefeated in two world championships. A euphoric national team arrived back in Canada with its second gold medal, exhilarated by its second successful world competition and the rising status of women’s hockey in other countries.

Despite Canada’s second gold medal, media interest in the world championship was low. With less than a handful of reporters covering the games, the press room was conspicuously quiet. The CAHA, which sent their communications manager to the men’s world junior championship, did not bother to do so for the women’s world event; instead they foisted the media relations job on the already overburdened national team manager, Glynis Peters. Moreover, some of the press complained about Peters’s inexperience and unwillingness to allow sufficient access to Team Canada. Nor did the CAHA apparently deem the championship important enough to secure television coverage. TSN did not broadcast any games, citing lack of advertising money and costs for the transatlantic feed as their reason for not doing so. What media attention there was mainly surrounded Manon Rhéaume. The word was out in hockey circles that Rhéaume was invited to appear in Playboy. European papers picked up the story and dwelled on it tediously, displaying only lukewarm interest in the other athletes.

The most significant event of the 1992 world championship, however, occurred off the ice. Representatives from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) attended the games to assess women’s hockey for inclusion in the Olympics. The CAHA, OWHA and IIHF lobbied for Olympic acceptance at cocktail parties and in improvised huddles in the stands. Letters of support were drafted by the CAHA and OWHA, who urged the IOC to establish women’s hockey as an Olympic sport in 1994 in time for the Olympics in Norway. In the summer of 1992, the CAHA announced that women’s hockey had been accepted into the Olympics—but not in time for 1994. Norway, apparently, would not cover the additional expense of adding the sport. The Japanese Olympic Committee (JOG) agreed to launch women’s hockey, however, at the 1998 Olympics in Nagano, Japan after months of negotiations with IIHF representatives, with input from the CAHA.

Team Canada’s participation in the 1998 Olympics will mean more than just long overdue recognition. “The Olympics have an aura,” said the OWHA’s Fran Rider. “It’s something special, it’s credible ….”20 The impact will be felt at all levels of women’s hockey. For provincial hockey organizations, it is a chance to build on the momentum of women’s hockey’s rising status, which will attract new players and coaches along with government funding that is increasingly geared towards Olympic sports. It is also an opportunity for the thousands of girls and women across the country for whom hockey is a passion to train with new hope. At last women will join their male counterparts at the ultimate amateur competition, the Olympics.

But for now Team Canada’s immediate challenge was “going for the three-peat,” the catchphrase describing its goal for the 1994 world championship in Lake Placid, New York. Only once before had three consecutive gold medals been won by a Canadian national team. (Canada’s men’s senior national team won the world championship three times from 1951 to 1953.) The CAHA chose as head coach the preppy, thirty-six-year-old Les Lawton, an eleven-year veteran with the Concordia Stingers in Montreal. Lawton had already proven himself: the Stingers had won several league championships and Concordia was known for its dedicated varsity program, which attracted female players from across Canada and the US. For the first time ever, both assistant coaches for Team Canada were female: Shannon Miller, an assistant coach in the 1992 world championship and for Team Alberta at the Canada Winter Games in 1991; and Melody Davidson, from Castor, Alberta, a recreation director involved in women’s hockey schools.

The competition to make the team was unprecedented. “It felt like I was trying out for the first time,” said two-time world champion Geraldine Heaney of Weston, Ontario. “The level of play was much higher and more evenly spread out this year. Some of the younger players were fantastic, and I’m looking forward to playing with Hayley [Wickenheiser]. She’s awe-some.”21 Fifteen-year-old Wickenheiser, from Calgary, Alberta, surprised everyone with her intelligence and maturity both on and off the ice. As Coach Lawton surmised, “Hayley might already be better than any player we’ve seen in the game. She’s really skilled, has strength and speed and is very bright. There are others like her coming up and ready to make a statement. That’s why the future is so good for women’s hockey.”22

The composition of the national team was changing. Two-time veterans France St. Louis, Geraldine Heaney, Angela James, Stacy Wilson, Judy Diduck and Margot Page all won places on Team Canada. Seven players represented Quebec, including 1992 returnees Nancy Drolet, Danielle Goyette, Nathalie Picard and Manon Rhéaume. Another eight new players joined this high-velocity roster. But it took time for the blend of veterans and youngsters to gel. In an exhibition game the week before the world championship, Finland defeated a disorganized and tentative Canadian team 6–3. Worried fans began to wonder if the Canadians could overcome their initial jitters and thwart their most consistent rival, the US, in their final exhibition game before Lake Placid.

During the game, the US team attempted to outmuscle the Canadian team and slow them down against the boards and in the corners, a foreshadowing of its strategy for the world championship. But the tactic failed. Canada squeaked out a 3–2 victory in a ragged game with twenty-six minutes of penalties. Backstopping Canada, Rhéaume recorded twenty-five saves and was voted MVP of the game. Wickenheiser scored the winning goal and contributed an assist.

Much of the media attention continued to focus on Rhéaume. Although she arrived at camp vastly improved—trim and muscled after two years of training in the semi-pro ranks—her celebrity status once again gave her an added advantage in the selection process. For the newly launched Canada—US Challenge Cup game played at the Ottawa Civic Centre, the pre-game radio and television promotion focussed almost exclusively on the goalie. Still lacking confidence in the drawing-power of women’s hockey, the CAHA and sponsors clung to Rhéaume’s celebrity status, viewing it as a surefire way to attract spectators. Although young male and female fans clamoured to see Rhéaume, they also lined up for autographs from the rest of Team Canada, excited more by their on-ice skills than the media-made interest.

With the Olympics only four years away, the pressure was on all the teams to step up their play. In 1994 Canada, Finland and the US once again set the standards for play. Canada rolled through its A Group, starting with a 7–1 win over the Chinese, who had dramatically improved their passing and skating skills but persisted in extra shoving and hooking to compensate for lack of experience. An ankle injury Wickenheiser received during practice kept her off the ice for all but five minutes of the China game. (She returned later in the tournament to play against Finland and the US, but was ineffective because of the injury.) The two Scandinavian countries fell prey to Canada next: Norway bowed out 12–0 and Sweden 8–2. The determined Finns lost in the semifinal 4–1. In Group B the US subdued Switzerland 6–0 and Germany 16–0. The US team’s biggest test was against the fleety Finns, but they salvaged a 2–1 win. In the semifinal the US toyed with China easily winning 14–3.

The final showdown of the championship pitted the highly favoured Canadians against the hometeam United States for the third time. Karen Kay, assistant coach in 1990 and now in her second year as head coach at University of New Hampshire, guided Team US. Its talented line-up included oversized goaltender Kelly Dyer, the three-time national team veteran who played for the West Palm Beach Blaze in the men’s semipro Sunshine Hockey League. Dyer, who towered over her teammates and the competition at 5 ft. 10 in. (179 cm) and 172 lbs. (78 kg), was joined in the US line-up by Cammi

Team Canada celebrating their world championship gold medal in Lake Placid,

Granato and Karyn Bye, all-star forwards from the 1992 championship.

After being thrashed 8–0 by Canada in the 1992 gold medal game, the US was hungry for revenge. Fans anticipated a fierce match and they were not disappointed. The US led 1–0 at the end of first period. Then Danielle Goyette popped the first goal for Canada on a power play at the beginning of the second period. But it was Angela James who charged up the Canadians. In a magnificent solo effort, she jetted down the left wing, faked a slapshot against the defence, then swooped in and flipped a shot over the goalie. A few minutes later she scored again, and by the end of the second period Canada led 3–2.

In the third period, another power play goal by Danielle Goyette and markers by captain France St. Louis and Stacy Wilson dashed the spirits of the young US team. Canada won 6–3 in a heart-stopping game that was still undecided until midway through the third period. The US had blown it by taking bad penalties. It was the second-most penalized team in the tournament, picking up eight out of the ten penalties in the final. “The penalties hurt. They killed our momentum,” confirmed US forward Karyn Bye.23 Whatever the reasons for the US loss, in 1994 Team Canada made hockey history by becoming only the second Canadian team ever to win three consecutive world championships. (In 1995 Canada’s male junior national team won a third consecutive gold medal in the world championship in Alberta.)

Once again, Canada dominated the all-star team. Canadian stars included Danielle Goyette who had been top scorer for Team Canada for the second time; goaltender Manon Rhéaume, and Therese Brisson on defence. Twenty-year-old Finnish sensation Riikka Nieminen and two US players, forward Karyn Bye and defence Kelly O’Leary, completed the all-star roster. Geraldine Heaney earned best defence honours and Angela James was chosen as MVP for the final game. Nieminen was named top forward with four goals and eleven assists in five games and Finland took home the bronze medal for the third time. China moved up to fourth place, even though it had a mere 250 registered players from which to select its team.

It wasn’t until 1994 that the CAHA finally sent Phil Legault, its manager of communications, to the women’s world championship to ease the burden on national team manager, Glynis Peters, who had juggled both the communications’ and manager’s job in 1992. But the CAHA still failed to aggressively champion its most successful and promotable product in the women’s game. TSN broadcast the history-making “three-peat” game, but fell back on the predictable: an interview with Manon Rhéaume and another historical look at women’s hockey. Moreover, Peter Watts, the TSN announcer for the final game, was clearly bored by this lesser assignment, making numerous mistakes with players’ names, and rarely allowing colour commentator and former national-team player, Sue Scherer, to express an opinion. Watts was even overheard grumbling earlier in the tournament that if the Finnish team made it to the final, he wouldn’t bother learning those difficult names: instead, he would just call the players by their number.

But Olympic status has conferred some benefits on Team Canada: in 1994 the CHA announced the formation of a coaching pool for the women’s national team. Six coaching trainees, five women and one man (who dropped out in 1995), would attend additional training courses and scout players at provincial and national championships. The coaching pool began to fill the need for elite female coaches, essential role models in the development of women’s hockey. Shannon Miller, two-time head coach, with five years’ experience with the national team, now mentors both male and female coaches for women’s hockey. Miller has been overwhelmed by the requests for advice. “I can’t believe the number of phone calls I get at home at night, from all over Canada. For the 1995 Canada Winter Games I had coaches from three provinces calling me for advice.” The fact that these coaches are constantly scouting players, at provincial and national championships across the country, forces aspiring young players to gear up under the additional scrutiny. It is also apparent that Olympic status dramatically affects how female hockey coaches and players are treated. “It affects the mentality of the men who are involved in the game,” explains Miller. “Before they could ignore women’s hockey, now they can’t. It’s real and we could win gold. The men are taking the game a lot more seriously.”24

Olympic status has meant that sponsors are slowly discovering Canada’s “other” national team. As mentioned in Chapter 7, in 1994 the CHA announced that Imperial Oil would be a new sponsor for its women’s national team, part of the CHA’s new premier sponsor package. The Royal Bank and Air Canada are also part of the premier sponsor contract with the CHA and between them doled out $25,000 for the Pacific Rim tournament in 1996. Unfortunately neither the CHA nor the sponsors will indicate the total amount of money which actually goes towards Canada’s female national team.

The inclusion of women’s hockey in the Olympics also prompted the IIHF to add international competitions. In April 1995 the IIHF launched the Pacific Rim championship to offer China and Japan a chance to sharpen their skills prior to the Olympics. For Team Canada this meant two extra national team selection and evaluation camps in October 1995 and 1996, as well as additional international competition.

In preparation for the 1995 Pacific Rim championship, the CHA implemented two significant changes. For the first time it chose an all-female coaching staff, with Shannon Miller acting as head coach and newcomers Julie Healy, assistant coach of the Concordia Stingers, and Daniele Sauvageau, a police officer and head coach with Ferland–Quatre Glaces in Montreal. Both assistant coaches are part of the Quebec senior all-star program. The CHA also chose a developmental team composed of sixteen rookie players, bolstered by previous national team veterans such as goalie Leslie Reddon, Judy Diduck, Stacy Wilson, Danielle Goyette, Marianne Grnak, Cassie Campbell, and sixteen-year-old Hayley Wickenheiser. The most imposing player on the Canadian team, now 5 ft. 9 in. (174 cm) and 170 lbs. (75 kg.), Wickenheiser challenged allcomers with her in-your-face hockey, playing on the first line with scoring ace Goyette and playmaker Wilson.

The outcome of the first two games was predictable: Canada humbled China 9–1 and Japan 11–0. In game three, against the US, Canada’s defence faltered, unable to contain the bigger, more experienced Americans. Team USA outskated the rookie Canadians, beating them 5–2. In the semifinal the unthinkable almost happened: the aggressive and brash Team China fought to a 2–2 tie after three periods. Canada managed to squeak by China 3–2 in a shootout, with goaltender Leslie Reddon thwarting the nervous Chinese forwards who were shooting in their first overtime. The gold-medal game against Team USA spoke volumes about Canada’s gritty determination and character. With players injured from the China game—Goyette and Grnak were in neck braces and Wilson’s legs and shoulders were black and blue from the excessive slashing and hooking—coach Miller stoked up the Canadian defensive game with aggressive forechecking and tight backchecking. The score was tied 1–1 after three periods with goals by Wickenheiser and Team USA’s Karyn Bye, although the US outshot Canada 36–23. Canada calmed down in the deciding shootout and was rewarded with a win when several US players choked and shot over the net. Wickenheiser departed the tournament several pounds heavier, thanks to three awards for her contribution to the team, including the MVP award in the final game.

The fact that a team of sixteen rookies with two new assistant coaches had defeated the US team in a tournament that most observers expected the Canadians to lose was yet another instance of Team Canada’s determination to prove its mettle. “It had a lot to do with motivation—to play for their country and national pride,” says coach Miller. “We stressed making history, playing and winning in the first Pacific Rim championship. The team played over their heads and were willing to pay any price for their country.”25

The CHA again selected Shannon Miller as head coach for the 1996 Pacific Rim tournament. Miller, the head coach of the new Olympic Oval High Performance Female Hockey program in Calgary, Alberta, has become a key role model for players and coaches. She possesses superb technical expertise and facility for motivating players. Two new assistant coaches—Karen Hughes, with the University of Toronto Lady Blues, and Melody Davidson, head coach for Team Alberta in the 1995 Canada Winter Games—completed the coaching staff. In announcing the new team, Miller pointed out the need for the development of elite players to move forward. “For the past two years, we’ve been evaluating and initiating players at an introductory level,” maintains Miller. “We’re now going to take these players to the next level of preparation for international games.”26

Team Canada 1996 represented the culmination of the gradual evolution of the women’s high-performance program since its rather chaotic beginning in 1990. With the new coaching pool, the CHA was finally able to scout both future and existing female players. The results were evident. This team was a formidable blend of veterans, including three-time gold medalists Angela James, Judy Diduck, Stacy Wilson, Geraldine Heaney, thirty-seven-year-old France St. Louis and Quebec scoring aces Danielle Goyette and Nancy Drolet. The mix also consisted of new, young players from both the 1994 and 1995 teams, including seven rookies and the number-one-rated player in the country, Hayley Wickenheiser. Danielle Dube, now Canada’s highest ranked goaltender, and Manon Rhéaume shared the net duties.

The Pacific Women’s Hockey Championship (the name was changed in 1996) offered an opportunity to assess Canada’s team against its most formidable opponent, the US. It was also a glimpse of the state of hockey in Asia. Japan’s small and inexperienced players—the average height is 5 ft. 2 in. (157 cm)—had little chance of winning against any of the teams. Canada routed Japan 12–0 in its first game. The Chinese remained a stubborn, tough team, who were able to confound the Canadians with their defensive box, thwarting the Canadian scoring threat. Once again, Team Canada barely managed to win, beating China 1–0, after being frustrated by the exhaustive goaltending of China’s Hong Guo.

The US, with its youthful energy and bolstered defence, also tested the Canadians. The first game against the US in this tournament was marked by end-to-end rushes. But Canada’s depth eventually wore down the US, which was using only two lines. The final score was 3–2 for Canada. Canada now faced Japan in the semifinal, an easy win by a score of 19–0. The gold medal contest between Canada and the US was more of the same. The game was scoreless until five minutes into the third period when the US popped its first goal. Canada’s speedsters took over: Nancy Drolet fired two goals and Cassie Campbell blistered a slapshot. Wickenheiser scored into the open net in the last five minutes of play. Goaltender Danielle Dube made thirty saves and was named MVP of the game. The local media warmed to this first international event in BC but TSN did not televise the final game which Team Canada coach Shannon Miller called “the best hockey ever played by the two best teams ever on ice.”27

This national team is the first stage of the five-year development plan for Team Canada, which began in the fall of 1995. The next task will be the selection of the head coach for Canada’s first Olympic women’s hockey team by August 1996. It is most likely that this person will be Shannon Miller. In the fall of 1996 Team Canada will play in a ten-day warm-up tour in Ontario and Quebec against the two top teams, Finland and the US. At a selection camp in January 1997, the CHA will choose the pre-Olympic team to play in the qualifying world championship in Kitchener, Ontario, in April 1997.

The last selection camp for players hoping to win a spot on Canada’s first Olympic team will be in August 1997. Once chosen, the team will likely relocate to Calgary in October to train together for four to six weeks, then go back home until January 1998, when they will convene for another training session, which will continue until just prior to the Olympic Games in February. For the hockey players, this Olympic schedule is close to athlete heaven: the players will be on the ice every day, attending strategy sessions and working with coaches. Facilities and all expenses will be paid by the CHA. And for the first time, members of the national team will address high school students, hold clinics and attend public-relations events—things the men’s national team has been doing for years.

Watching the CHA play catch-up with the women’s high-performance program is both gratifying and frustrating. Elite hockey is an important catalyst that has pushed the development of the women’s game farther and faster. But even Team Canada sits at the end of the bench when it comes to financial and marketing support from the CHA. While player evaluation and coaching development has improved dramatically, elite female players are still only beginning to benefit from the advantages and privileges male players have enjoyed for years.

The sheer number of elite male teams and the range of competitions is staggering. The CHA Program of Excellence (POE), begun in 1982, is an example of a very successful system committed to developing the highest calibre of male players for Canada’s national junior team. The POE boasts a database of statistics on all elite male hockey players in Canada, starting at age sixteen. The CHA employs a full-time scout to tour the country and report on players. The POE consists of a three-stage plan involving the development of elite male players starting at age sixteen. At the first stage the players try out for the five regional under-17 Canadian national teams that face off against Russia, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Finland and the United States. Canada hosts this World Hockey Challenge, which is held every two years. In alternate years there is either a Hockey Festival or the Canada Winter Games to pit the five regional Canadian teams against one another. The next stage consists of an annual four-country under-18 championship, in addition to the Air Canada-sponsored under-18 Pacific Cup. The third stage involves selection and training camps for the national junior team and its participation in the annual world championship. Keeping this revolving door of tournaments spinning takes commitment and cash, both of which are in secure supply for the men’s national teams.

To develop Canada’s senior male team Hockey Canada, a second national hockey organization, was launched with government funds and sponsorship in 1964. Hockey Canada’s responsibilities included the Canada Cup tournaments, and the organization employed a full-time head coach, assistant coach and general manager for Team Canada. By 1993–94 the men’s tour consisted of sixty-five games in Europe and Canada. In 1994 Hockey Canada merged with the CAHA under the new moniker the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA). The senior men’s team will no longer represent Canada in the Olympics since the NHL, IIHF and IOC have agreed to NHL “dream teams,” starting in 1998.

Elite male players do very well, revelling in the perks of competition as early as age sixteen. Yet to hear those involved with the men’s national team tell it, they are barely scraping by. “We operate on a shoestring budget,” Canada’s coach Tom Renney lamented in 1994. “Our total budget is less than $500,000 and from that we have to give twenty-two guys contracts, equipment and supplies, travel costs. It all adds up. Only a small percentage of our budget comes from the government, but since the merger with the CAHA the government is playing a more direct role so we’ve been affected by the cuts.”28

Female national team players are not paid a salary and will not be training year-round prior to the Olympics. “Certainly the women are not going to train on a full-time basis like the men’s team,” says manager Glynis Peters. “It would drive them nuts. For one thing, you’d be asking people to give up friends, family, jobs. We think we can build a plan that gets them to the Olympics with the best team and still keep some balance in their lives.29 The CHA seems unaware that many of the players, including Manon Rhéaume, are planning to leave jobs and pay to train full-time at the new women’s hockey high-performance program at the Olympic Oval in Calgary. Many of these women have to pay just to play the game. New Brunswick’s Stacy Wilson not only loses her teaching salary when she attends a camp or tournament, she must also pay the substitute teacher who replaces her.30

For the first time the women’s national team will receive “carding” as Olympic athletes, which entitles them to Sport Canada funding to train. In the fall of 1995, thirty female hockey players were carded to receive money for two years. This infusion of funds allows the athletes to pay at least for such things as new skates and even memberships to sports clubs. For example, Team Canada member Angela James cannot afford to quit her job, but with her carded status she can now get advice from a personal trainer on how to supplement her regimen.

The difference between men and women’s teams lies almost entirely on the CHA’s financial commitment. In 1994–95 the CHA budget showed government revenue for Canada’s national teams is listed at $625,500. Although CHA officials will not divulge how much of that goes to the women’s team, the women’s national team expenses were listed as a meagre $25,210. This compares to $1,833,885 allocated for the men’s senior and junior national teams and the national under-17 and under-18 programs. The CHA might argue that the junior and senior men’s teams pay their way with gate receipts totalling $1,784,000 from play in the heavily promoted world championships and tournaments, where prize money is offered.31 But given the same marketing and administrative support male hockey receives, it is conceivable that Canada’s female national team could also pay for themselves.

Advancement of Canada’s female national team should mean sharing more of the sponsorship opportunities, staff, and federal government funds allocated to the CHA. In a climate resistant to female sport, championing the relentlessly successful Team Canada is one easy strategy for advancing women’s hockey. Yet the team’s success is often perceived as a threat to the men’s game because female hockey is seen as competing with male hockey for crucial components such as ice time, volunteers, government funds and sponsorship. Indeed, the remarkable success of the female game and the increase in participation are at times viewed as an annoying distraction to male hockey. Women’s hockey emphasizes finesse and agility, and is devoid of the fighting and violence so prevalent in male hockey; this is a formula that spells family entertainment. For parents and fans who dislike the goon mentality promoted in the media, women’s hockey is a refreshing alternative. Yet, practically speaking, the CHA and its provincial counterparts have a case of conflicting interests. If they aggressively promote Team Canada, they are diluting male hockey resources by encouraging female players. Women’s hockey is cutting into the opportunities for male players, whose membership fees and sponsorships have been paying the CHA staff salaries for years. CAHA President Murray Costello expressed this fear in the wake of the 1990 women’s world championship. “The biggest concern I have for the CAHA is how we’re going to share already scarce ice time between girls and boys, especially in small-town Canada,” he said. “We’re not sure what we’re creating here.”32 That the organization should be creating equal opportunity for girls seems to elude him. But by neglecting Team Canada the CHA is ignoring a hugely successful hockey property that is not only likely to win one of Canada’s gold medals but can boost registration and line the CHA’s coffers.

Despite the neglect, the women’s national team remains a beacon of hope in the barren hockey landscape of little-known female heroes. And its performance has not gone unnoticed among female sports advocates. “The women’s national ice hockey team which made history in 1994 by winning a third consecutive medal in world championship play, had an impact far beyond the ice surface,” declared the selection committee for the Breakthrough Award presented by the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport (CAAWS) to Team Canada in 1995. “Their style of play and outstanding success have captured public attention and raised the level of competition to international standards.” The players’ dedication also helped to win them the award, which recognizes individuals and organizations whose accomplishments have pushed the limits and enhanced the participation of girls and women in sport and activity. “Many [of the women] played for years before a national championship existed and long before a world championship was ever conceived. Time off from work without pay, missed promotions, delayed schooling, hours of travel to practice were common sacrifices,” said CAAWS chair Bobbie Steen of Vancouver.33 Karen Wallace, volunteer director of the Female Council at the CHA noted with some amusement that after the third national team gold medal, she no longer had to watch half the CHA membership leave before she read her female hockey report at the annual meeting.

The significance of Team Canada for women’s hockey is profound. As Shannon Miller puts it: “You could credit the survival of women’s hockey to the national team. Players will go to another sport if there is no place to advance. The national team program is like a carrot and just as big as the NHL for women’s hockey.”34 For individual players, the importance of both hockey and Team Canada is palpable. In the hallway of Angela James’s townhouse in North Toronto hangs a large framed colour photo of the 1990 women’s world champions. With the proliferation of mugs, pucks, trophies and plaques, her home is more hockey shrine than residence. “My whole life is hockey,” says James. “I live and breathe it. I never thought much about it until I got older, but people say ‘Is that all you do is hockey?’ I step back and say ‘Yes. I coach, I referee and I play. That’s my life and I don’t think I would ever change it for anything else.’”35

Athletes like James play a fundamental role in the lives of young female players. In a drawer James keeps a poem dedicated to her by fourteen-year-old Jennifer Neil. For Neil, a grade eight student from an elementary school in Kitchener and a mixed-race child like James, AJ is an idol. Ever since Neil first witnessed James at a national team camp she’s been enthralled with AJ. “My four friends and I were sitting in the stands talking about who is the best player. I said number 8, she’s really good, I wish I could be like that,” recounts Neil. “Then something clicked in me and I wanted to set a goal for myself. The way she skated, her shot. She’s awesome. She looks so confident and comfortable out there. Even though it’s tough it didn’t get to her. Nothing will stop her.”36

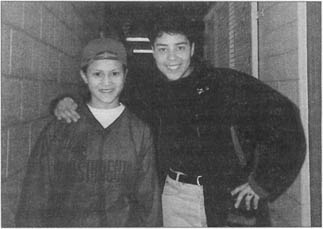

Jennifer Neil and Angela James at Canada’s national team selection camp, Kitchener, Ontario, January 1994.

After the game Neil asked James for her autograph. “I was so nervous I couldn’t breathe. [It was] like meeting Doug Gilmour [of the Toronto Maple Leafs].” Early in 1994 Neil had planned to quit girls’ hockey because the calibre was so low where she plays. She changed her mind after meeting James. “I decided to stay in hockey and went to Aj’s and Margot’s [Page] school that summer [1994] and improved a lot,” she recalls. “I really let her know I never would have [stayed with hockey] without her encouragement. I got a real confidence boost from her.” Hockey is now once again a significant part of Neil’s life. In 1996 she played on two junior teams.

The inspiration Neil received from James is testimony to the importance of visible female sports heroes. Not only do women such as James deserve admiration for their athletic feats, but girls such as Neil deserve role models. Indeed, as Neil herself makes evident, their presence can make all the difference in the world.