Traditionally, when discussing the beginnings of Enlightenment aesthetics, intellectual historians and historians of philosophy point to the philosopher Alexander Baumgarten, who set out to investigate the particularities of sensuous cognition.1 With the creation of a philosophical subdiscipline, which he called aesthetics, Baumgarten designated a domain that valued the lower faculties, that attributed to the work of art a specific insight-generating power, and that reflected on the pleasures of the imagination.2 For the purposes of this chapter, however, I shall bracket this approach. Instead of tracing a certain trend in philosophical discourse about the value of art and the specific kind of access to truth that could be provided by works of art, I shall turn to a set of practices and habits. I am interested in investigating what in the wider population of a general, not philosophically specialized readership would have prepared the ground for radically rethinking the nature of aesthetic pleasure, so that it would be considered no longer an exclusive domain of connoisseurs but instead would become valued as a universal human and humanizing capacity. I shall do so by investigating practices of attention, of serious, committed observation directed at seemingly trivial, mundane, quotidian phenomena, which in the process of contemplation would reveal to the observer a hidden significance. My goal is to show that these practices of attention ultimately served to form habits of cultivating a pure, pleasurable contemplation utterly different from the interested engagement with something agreeable, capable of satisfying the senses. Such practices of attention, capable of endowing objects of observation with the ability to elicit in the observer a pleasure that would transcend sensuous gratification, constitute an important component of many kinds of spiritual exercises and practices of sublimation that can be found throughout history. Thus it is the challenge of this chapter to isolate one specific strand of spiritual exercises, which would have been widespread and enduring enough to be considered relevant for having actually shaped a certain mindset of the general readership of that period.

The practices of attention and observation I shall isolate as the cultural site that prepared the ground for the promotion of “disinterested interest” as the key to Enlightenment aesthetics can be clearly distinguished from other practices of attention that also gained significance during the eighteenth century. In her “Attention and the Values of Nature in the Enlightenment,” Lorraine Daston examines how within the framework of natural theology the practices of observation of eighteenth-century naturalists lead to the enshrinement of the moral authority of nature expressed in Pope’s dictum from his “An Essay on Man”: “Whatever is, is Right.” She shows how such naturalists as Charles Bonnet would devote endless hours to highly focused attention on the lowliest insects, to recording the most exacting, detailed descriptions of these observations, but also to the pleasures and joys they would take in these thus individualized creatures beautified by the art of attention and description. Daston argues that it was especially the focus on “what Bonnet would call the ‘organic Economy’ in which the ‘arrangement and play of different parts of organized bodies’ explained operations like growth and generation” that would guide the focus of these naturalists to analyze “objects into interlocking parts” and trace “the fit of form to function with an eagle eye for ‘fitness.’”3

By contrast, the practices of attention that I will discuss in this chapter did not have as their goal the precise, detailed observation of natural phenomena within an overall framework of natural theology aimed at understanding and explaining the fitness and utility of each and every creature. Their aim instead consisted in the transformation of the observer and in the spiritual growth of the believer. And although these practices might focus on a mundane, lowly object, they are aimed at a spiritual realm beyond that of the senses. They are very distinct from the practices of attention of the naturalists, which involve the observer’s active interaction with concrete natural phenomena, placing them under the microscope, anatomizing, taking notes, and drawing details. The practices I shall study revolve entirely around the training of the observer’s own mental and emotional faculties. The activity of observing a specific sight or object is primarily a means to that other end, and in this regard such practices of attention are highly self-reflexive. These practices of attention began to take hold somewhat earlier than those studied by Daston, and they were much more popular. They emerged in the realm of popular religion, in Protestant areas during the seventeenth century.

In what follows I shall base my argument on the analysis of one of the most popular books among the vernacular literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Johann Arndt’s devotional guide Vom wahren Christenthum (On True Christianity). First published in 1605, True Christianity went through numerous editions throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and it was translated into many languages. The cultural influence of this book was enormous. Arndt’s True Christianity gave lasting shape to the form of piety that became known as Pietism.4 Its formative, pivotal role for the development and spread of this religious movement can be glimpsed from one moment in its publication history. In 1675 Jakob Spener (1635–1707), generally considered the founder of Pietism, chose to publish his critique of the orthodox church establishment and hope for both institutional reform and religious renewal, his Pia Desideria, as part of a preface to a new edition of True Christianity. Already this move—Spener’s decision to integrate his programmatic manifesto into the preface of Arndt’s by then established devotional guidebook—indicates the kind of intervention that was at stake in this religious reform movement: religion was to rid itself of doctrinal pedantry and institutional authority and be based instead on a lived, practiced spirituality.

Johann Arndt’s True Christianity went through numerous editions, was translated into many languages, and became, among the vernacular literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, one of the most widely read, or rather most widely used, books of the Protestant region of that time. It is a book that does not demand a linear reading, but offers itself as an organized resource of instructions for concrete exercises. In that sense, True Christianity is not a book that attempts to deliver a message but rather a guide that aims at recruiting practitioners. In order to get a better understanding of what was so special about Arndt’s approach to spiritual exercises, it is worthwhile to compare True Christianity with another quite popular devotional text. For Arndt was not the only one composing Protestant meditational literature. Beginning with Martin Luther there was an entire tradition of cultivating meditation as a means by which believers were to practice making connections between biblical passages and their own lives. A popular work of Protestant meditational literature (though not quite as popular as Arndt’s) was Johann Gerhard’s Meditationes Sacrae. Its first edition appeared in 1606, just one year after the first edition of Arndt’s True Christianity. Gerhard’s Meditationes were published first in Latin, then also quite frequently in German, and other translations were made into vernacular languages, including translations into verse. Although some editions of Gerhard’s Meditationes were augmented by visual emblems, these never achieved the lasting impact of the equivalent illustrated editions of Arndt’s True Christianity. The most important difference consists in the way in which the meditations are presented. Gerhard’s Meditationes offer a mixture of prayer and admonition with reflections on aspects of the religious message. They are primarily an ongoing back and forth between the address to God and the address to the believer’s soul. They are only interrupted by admonitions to the believer to remember crucial elements from the life and suffering of Jesus and to apply those to her or his own life. Arndt’s meditations, by contrast, as I will show, are quite differently composed. Whereas the meditation in the case of Gerhard is provided by the verbal text of each meditation as a complete unit, which could be compared to a “libretto,” providing the actual words of prayer to God or Christ, of admonishing one’s own soul, of lamenting one’s own depravity, etc., Arndt’s meditations work like a rebus, a complex set of narratives and images that involve the reader more actively and take the reader beyond the text of the meditation. For they focus the readers’ attention on external, secular phenomena, which then are to be considered and compared in their complex way of functioning to a religious phenomenon.5 Thus it is Arndt’s very special use and selection of images that sets his work apart from other devotional literature of his time.6 In Arndt’s work we can find a deployment of images that crucially involves the external, secular world for meditational purposes, an aspect that I will argue had a deeply transformative potential for this religious practice in the sense that it opened it up for its migration toward an exclusively secular context.

In what follows I shall first show how Arndt’s text makes use of verbal images, of similes and comparisons, for the famous visual illustrations were not added to Arndt’s text until the Riga edition of 1678, about fifty years after its author’s death in 1621.7 Then I shall turn to these visual emblems, which in 1696 were enriched by prose explanations. I shall show how these illustrations together with their prose commentaries isolate and heighten the spiritual exercises that are already part of the verbal text such that they prepared the grounds for the cultural practices of observation, contemplation, and reflection that by the second half of the eighteenth century would be considered constitutive of aesthetic experience.

The main goal of True Christianity is to guide each individual believer to become a better Christian, which means to bear the hardships of life without anger or complaint, and to reflect on the basic religious doctrines in terms of their applicability to the reader’s own life. The fallen nature of man, the nature of true faith, the value of patiently enduring suffering—these religious truths are carefully explained in view of complex verbal images that the reader is asked to contemplate.8 Thus, for instance, the second chapter of True Christianity is entirely devoted to bringing home the message of man’s fallen nature. Arndt’s readers are to see themselves as sinful and in dire need of redemption. His method of getting his readers deeply involved in thinking about the fundamental Christian dogma of original sin and applying it to their own lives is already captured in the table of contents below the title of the second chapter:

1) Adam’s fall as the most terrible sin. 2) Can be made clearer by looking at Absalom’s sin. 3) Through which man began to resemble Satan. 4) From this poisonous Seed grow the most horrific fruits, 5) Which already stir in little children, and which are augmented by anger. 6) This poison is hidden in the heart but breaks out in life. 7) This is why anger is strictly forbidden. 8) The fall and original sin [Erbsünde] cannot be eradicated; 9) Because it turned the human being into a beast; 10) thus that man will have to perish in that state unless he converts.9

Arndt selects as the key biblical passage for his discussion of the Fall not Adam’s and Eve’s transgression from Genesis but Absalom’s rebellion from the book of Samuel. Through this move he turns what could be viewed as a single event in human history into a universal human trait. For Absalom’s rebellion exemplifies for him a ubiquitous human flaw, a son’s aggression and competition with his loving father. He thus begins explaining the fallen nature of man with a universalizing gesture, depicting it as a result of a human tendency that can be commonly observed. Only then is the Fall explained as a radical transformation of a creature that initially was an image of God but then became an image of Satan. The eating of the forbidden fruit is not the cause for the expulsion from paradise, the first act of disobedience, but merely a symptom of man’s perverted heart, understanding, and will.

Arndt’s use of verbal images can be further studied when he sets out to get his reader to imagine the concept of original sin: how the distinguishing feature of man, a creature who originally was created in the image of God and then transformed into its opposite, the image of Satan, was to be passed on from generation to generation. He proceeds by blending two images with one narrative, by having his reader think of a natural seed, invoking the image of the serpent-seed from Moses 3:15 to which he adds the adjective poisonous, and then by embedding this combined image into his retelling of the narrative of the Fall:

For just like a natural seed in a hidden fashion contains all features of the plant, its size, thickness, length and breadth, its twigs, leaves, bloom and fruit, such that a big tree is hidden in a tiny little seed, and so many, innumerable fruits; this is exactly how in the poisonous, evil serpent-seed, in Adam’s disobedience and self-love, there is hidden for all progeny inherited through natural birth such a poisonous tree, and so many innumerable evil fruit, that in those the image of Satan with all evil behavior and character will appear.10

The concrete, commonly observable phenomenon of the seed is supposed to provide an analogy for how the Fall is to be passed on to the entire species. Yet instead of providing an explanation of how the transmission of man’s altered state works, Arndt’s image makes the fact of that transmission as natural as trusting the apple seed to contain all the traits of the tree that will grow from it. Moreover, while this image naturalizes a point of Christian dogma in everyday experience, it also isolates a humble, everyday phenomenon, such as a plant seed, and invites the reader to contemplate its hidden complexity and latent danger. In what follows I want to argue that it is this kind of isolation and focus on relatively commonly observable phenomena, which are framed as bearers of a complex significance, that not only provides the key to the long-lasting popularity of Arndt’s work but also lays the groundwork for a kind of observational practice that eventually would become the domain of aesthetic experience.

By aesthetic experience I mean not only the basis of an aesthetic judgment as it is analyzed by Kant in his Critique of Judgment in terms of the “disinterested interest” we take in the object of aesthetic pleasure, but also the kind of practice that made a much earlier appearance in Shaftesbury’s and Herder’s notion of “contemplation” or in Addison’s discussion of the “Pleasures of the Imagination.”11 The entire spectrum of contemplative practices that could be bundled under the rubric of aesthetic experience neither takes the engagement with art or artistic performance as its model nor derives from a culture of connoisseurship, a culture in which aesthetic appreciation and taste become a marker of social distinction. On the contrary, the kind of aesthetic experience for which I claim Pietist meditational practices laid the groundwork must be in principle universally accessible as it is also not at all engaged with the actual existence of a particular object, but much more engaged with the self-reflexive dimension of a perceptual practice.

Arndt’s text marks a curious juncture between, on the one hand, the tradition of Baroque emblem books, which dominated the sixteenth and seventeenth century with their artful combination of visual and verbal materials, and, on the other hand, the seventeenth-century use of primarily often exclusively verbal emblems for religious instruction, for sermons, and in devotional literature. Whereas during Arndt’s lifetime True Christianity clearly belongs to that newer tradition that transformed the use of emblems from the expensive art book into a purely verbal device of devotional literature, beginning with the Riga edition of True Christianity in 1678/79, visual illustrations of the combined verbal/visual emblem tradition were added and kept for many, but by far not all, subsequent editions.12 In the following I will base my argument on these illustrations because they highlight one aspect of the specific use of images in Arndt’s True Christianity that is already a crucial component of the verbal images, namely the isolation of an unremarkable phenomenon, rendering it worthy of notice and contemplation, as we have seen, for instance, with regard to the image of the seed. In addition, in that these visuals are explained, framed, and presented with different kinds of instructions and clues for the reader as to what to do with them, they provide my argument with more explicit material to study the actual practices of observation and attention that were propagated by True Christianity.

According to the introduction of the Riga edition of True Christianity in 1678/79, the newly added visuals are to “instruct the lover of True Christianity how to awaken at any time his mind to devotion, abstract it from earthly concerns and elevate it to God by contemplating things occurring in nature or art.”13 This instruction deserves to be read carefully. It seems to say not much more than what is expected from most spiritual exercises, namely that they are supposed to train the believer’s attention to move away from the material world to the spiritual realm. But how is this to be achieved? It is to be achieved by “contemplating things occurring in nature or art,” i.e., natural phenomena and man-made things. Moreover, the reader/beholder is not to remain with the book or the visual illustration, but rather the whole point of the illustration consists in alerting and stimulating the reader’s contemplative activity such that it would be set into motion by phenomena occurring in everyday life. In other words: these emblems first show the beholder how to focus on phenomena to be observed in the reader’s own reality and world, outside the confines of the book. Then they lead the believer’s contemplation from this-worldly things to the devotion to God.

The fifty-six plates are not identical in theme with the guiding metaphors or similes from Arndt’s verbal text, but in their way of functioning they follow the same pattern as Arndt’s verbal images. For instance, whereas the verbal image in the text of the chapter about the Fall revolves around the seed’s latent power of transmission, the visual emblem added to this chapter shows a camera obscura (figure 1.1). This is to illustrate how the Fall has turned man, an image of God, into an inverted image, i.e., the image of Satan. There is, however, nothing intrinsic to the optics of a camera obscura that offers itself as an illustration of the meaning or significance of the Fall, its implications for what it means to be human. Instead the beholder is to conceive of the Fall as self-evident or natural as the fact of the upside-down image produced by a camera obscura. The facticity of the Fall is set into analogy with the effect of a commonly observable optical medium, which the observer knows obeys the laws of optics, that he or she nevertheless cannot explain or easily grasp and is not to attempt to do but rather to accept and marvel at.

Indeed, the range of thematic choices for the illustrations in the Riga edition is quite telling. They are from the domain of tools and optical or print technology, the domain of natural phenomena of the macrocosm, but they also include observations, such as what happens when one is shouting in the mountains and creates an echo (figure 1.2), or if one tries to burn green branches (figure 1.3), or how a candle would attract and potentially burn insects (figure 1.4), or how a straight stick in a glass of water counterfactually appears to be broken (figure 1.5), or how chopping onions makes one cry (figure 1.6). The illustrations almost always present interesting, puzzling, but also quite predictable, and in that sense orderly, natural processes and mechanisms.

FIGURE 1.1 “Verfinstert und verkehrt” (Darkened and upside down). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

These emblems must neither be understood as signs harboring a specific meaning nor as pictures representing something. Instead, they function as a model for the reader’s imaginative engagement with the natural or mechanical processes toward which they direct the reader’s attention. By generally omitting the depiction of an entire human figure, the emblems invite the reader to place himself or herself imaginatively into the situation or process to be contemplated: thus an image of two hands peeling and chopping an onion is more directly analogous to the reader’s own experience of peeling an onion than if the image were of a housewife sitting at a table chopping an onion (figure 1.7). In fact, I would argue that this latter image, from an early nineteenth-century edition of True Christianity, the one that adds the human figure peeling the onion, marks the point in time when the kind of practice of attention propagated by True Christianity could no longer be associated with the use of devotional emblems. The role of these images as armatures or scaffolds for the imagination of the reader, prompting him or her to actively engage with processes and mechanisms as part of his or her own realm of lived experience, could also explain the rather conspicuous omission of references to the Bible. Through Arndt’s text the reader is situated in her or his everyday environment and lived experience; it is from there that the spiritual exercise is to take off rather than from remembering biblical passages.14

FIGURE 1.2 “Zur Antwort fertig” (Ready to respond). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.3 “Je härter Krieg/Je edler Sieg” (The harder the war/The nobler the victory). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.4 “Nicht zu nahe” (Not too close). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.5 “Dennoch gerade” (And yet straight). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.6 “Nicht ohne Thränen” (Not without tears). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.7 “Nicht ohne Thränen” (Not without tears). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum. Stuttgart, 1855. Scan of reproduction in Elke Müller-Mees, “Die Rolle der Emblematik im Erbauungsbuch aufgezeigt an Johann Arndts ‘4 Büchern vom wahren Christenthum.’” Dissertation. Universität Köln, 1974.

Arndt’s work does not operate within the framework of a general teleology. Instead, the world projected by his work entails many latent, puzzling, natural ways of functioning that have their own hidden teleology, which, however, cannot be conceptually grasped, but can become the occasion of absorbed wonder and contemplation. This explains why the Riga edition, in its unequal distribution of its fifty-six plates, devotes only one visual image to the chapter on the creation of the macrocosm, an image of a printer’s workshop with the boxes of individual letters and the motto “Im Setzen lieset man” (One reads as one is putting together the letters; figure 1.8). And the chapter about the creation of all living beings is prefaced by the visually rather stunning emblem of a pair of glasses and the motto “Durchhin auff etwas anders” (Through it on toward something beyond; figure 1.9). The creatures of this world should serve us like spiritual spectacles through which we will focus our love of the creator. The fact that Arndt’s True Christianity did not subscribe to a teleological approach to nature, where the careful observation of actual natural phenomena would lead us eventually to glimpse aspects of the creator’s intelligent design, an approach embraced later in the eighteenth century by many different kinds of observers of nature, deists and Pietists, like those naturalists discussed in Daston’s essay on the moral authority of nature, is relevant for my argument. We can see in Arndt a contemplative engagement with those “things from art and nature” with regard to their purposiveness, but we do not know exactly how they function, what makes them tick, nor do we have the clear concept of the mechanism we are contemplating. Propagating this kind of contemplative engagement with the world, especially as it is emphasized by the visual emblems that tended to dominate the many editions of True Christianity over nearly two centuries, Pietist meditational practice developed an everyday sensibility among broad swaths of the literate population, a mode of “contemplation” that then could be claimed to constitute a specifically human and humanizing capacity by the discourse of Enlightenment philosophy and aesthetics.

FIGURE 1.8 “Im Setzen lieset man” (One reads as one is putting together the letters). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum, ed. T. Kohler. Philadelphia, 1854. Butler Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.9 “Durchhin auff etwas anders” (Through it on toward something beyond). Johann Arndt, 4 Geistreiche Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (edited by Johann Fischer, printed by Johann Georg Wilcken). Riga, 1678/79. Scan of reproduction in Elke Müller-Mees, “Die Rolle der Emblematik im Erbauungsbuch aufgezeigt an Johann Arndts ‘4 Büchern vom wahren Christenthum.’” Dissertation. Universität Köln, 1974.

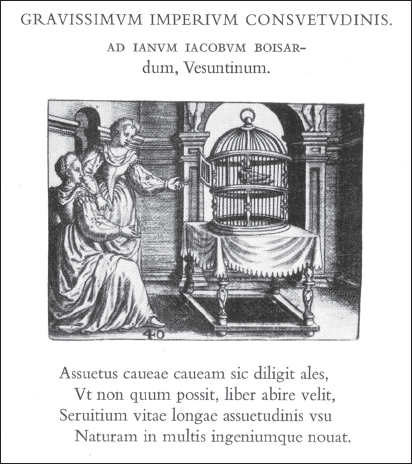

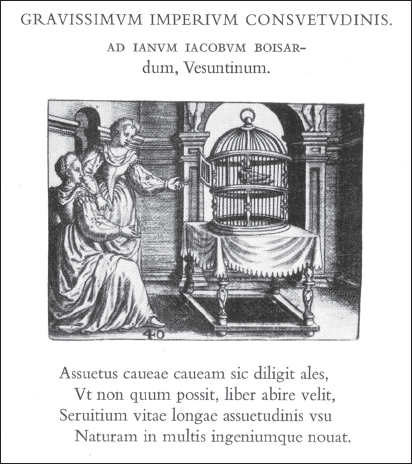

Especially with regard to their heterogeneity and their inclination toward the far-fetched comparison, the conceit, Arndt’s images resemble the typical Baroque emblem of the hybrid visual/verbal genre. Yet whereas much of this kind of wisdom literature invites its reader to reflect on the course of the world or life at court in generalizing terms, both Arndt’s verbal and visual emblems almost always involve the reader directly in those mechanisms or phenomena that are used to explain something central to the Christian faith. While in the Baroque wisdom literature the image of a bird in a cage is used to illustrate the force of habit, or where the bird is to stand for the voluntary prisoner of love (figure 1.10), in True Christianity the emblem appeals to the reader to identify with the bird: “Ich hab das beste davon” (I am better off in here; figure 1.11). The true Christian should feel so well taken care of by God that it would not make sense to escape from His providential oversight.

FIGURE 1.10 Dionysius Lebeus-Batillius (Denis Lebey de Batilly), DIONYSII LEBEI-BATILLII REGII MEDIOMATRICVM PRAESIDIS EMBLEMATA. Francofurti ad Moenum, A0. M. D. XCVI. Reprinted in Arthur Henkel and Albrecht Schöne, eds., Emblemata: Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts, 755. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1967. Avery Architecture and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

It is not just a Christian versus a worldly use that distinguishes Arndt’s emblems; rather it is in the exact functioning of the image, its role as a prop for the reader’s imagination, that we need to seek the specific contribution of these images. This can be observed in a Spanish advice manual for the Christian prince, by looking at how the image of a telescope (figure 1.12) is used to illustrate the distorting and dangerous aspects of flattery at court.15 The prose explanation tells the reader that flattery enhances the already regrettable discrepancy between the growth of desires and the late arrival of reason. By contrast, in Arndt’s work we find the image of a telescope (figure 1.13), and the prose explanation of 1696 reads: “Here we have a large tube perspective or telescope, through which the eye of the astronomer can look and perceive and recognize fairly clearly, very close up and present the most remote stars. In the same way the hope of a believing Christian has very clear eyes of faith, through which it can see through this-worldly visibility far unto the realm of invisibility, into God’s loving paternal heart and can delight in eternal splendor” (419). God’s otherworldly splendor is not to be grasped allegorically, by way of training one’s attention to one’s capacity for hope as if it were a perceptual apparatus, which then would transform our mere physical sight into a means of powerful vision of God’s invisible splendor. Instead, readers are asked to shape their own belief in analogy to how a telescope works: imagine and shape your mental attitude such that it functions like the telescope and lets you look through the worldly phenomena into the otherworldly.

FIGURE 1.11 “Ich hab das Beste davon” (I am better off in here). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

FIGURE 1.12 Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, IDEA DE UN PRINCIPE POLITICO CHRISTIANO, Representada en cien empresas. Cavallero &c.—AMSTELODAMI, Apud Ioh. Ianßonium Iuniorem, 1659. Reprinted in Arthur Henkel and Albrecht Schöne, eds., Emblemata: Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts, 1426. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1967. Avery Architecture and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

As opposed to Baroque emblems in general, both the verbal and visual emblems in True Christianity function as specific guides telling readers how to focus on common phenomena of the world in order to transform their inner faculties, be that the ability to bear suffering with patience, to hope, to trust in God, or to accept and fully experience the necessity of remorse. These images do not have the status of mimetic images; instead they are models for the contemplation of everyday phenomena. They might have the side effect of enchanting those everyday phenomena, of calling attention to their marvelous ways of functioning in a perfectly meaningful and predictable fashion, that nevertheless remains somehow opaque to the nonscientific layperson. They never appeal to the reader to figure out those mechanisms, to decipher from them any kind of religious, metaphysical insights about the nature of God, the purposes of creation, or the intentions of Providence. The interpellation of the reader as a true Christian in training, the imperative to seek out everyday phenomena as illustrations of the workings not of God but of the believer’s own spiritual faculties, proposes a contemplative practice, which is universally accessible and highly reflexive, ready to morph into a perfectly secular version, in which the pleasures of the imagination and what only much later will be called aesthetic experience consist in this practice of mindfulness, such as studying the self-reflexive effects of contemplating a purposiveness without purpose.

FIGURE 1.13 “Entfernet und doch zugegen” (Distant and yet present). Johann Arndt, Sechs Bücher vom wahren Christenthum (Zu finden in der Johann Andrea Endterischen Buchhandlung). Nuremberg, 1762. B239 Ar61, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. “Der Emblematik im Erbauungsbuch aufgezeigt an Johann Arndts ‘4 Büchern vom wahren Christenthum.’” Dissertation. Universität Köln, 1974.

Finally, one might wonder, where in this take on the history of Arndt’s emblems would one be able to situate the decisive secularizing moves? In my argument I have isolated three stages of an increasing potential for the severance of this kind of spiritual practice from its official religious authoritative context, such as the Bible and church liturgy. First, there is the isolation of and dwelling on those surprisingly complex and interesting everyday phenomena, which can already be found in Arndt’s very own verbal emblems. Then there is the enhancement of this tendency by the addition of visual emblems by the three Swedish government officials Dunt, Meyer, and Fischer with their edition in Riga in 1678. Finally, and this might be the most decisive intervention in this trend, there is the addition of prose explanations to the visual emblems beginning with the Leipzig edition of 1696. Whereas the visual emblems selected by Dunt initially were only explained in Meyer’s elaborate poems printed on the verso page, explaining both the picture and motto in relation to the biblical verse reference as well as in relation to the addressee’s own life circumstances in the form of what one might call a miniature sermon, the prose explanations that were added below the visual images did not take recourse to the citation of a biblical verse but remained entirely within the focus on the mundane phenomena that were used as conceits for spiritual matters.16 Thus whereas the initial visual emblem version of True Christianity would implicitly depend on the reader turning the page to the miniature sermon, once the prose explanations were added below the visual image this reference lost its function.

Once the image was combined with these prose explanations on the same page, it opened the door to a purely secular perusal, inviting its readers to wonder about its meaning, to seek in their everyday lives those seemingly mundane phenomena referred to, to contemplate their hidden, quite marvelous complexity, and to enjoy this act of contemplation and attend to it as a strengthening of one’s own spiritual capacities. In other words, we can witness in Arndt’s illustrated spiritual self-help book a popular guide that would encourage the actual practice of attending to the human capacity of pleasurably experiencing a disinterested interest, which marked Kant’s turn toward aesthetics, Kant’s attempt to find a radically other kind of human nature, the one experiencing itself capable of freedom rather than determined by self-interest.

Up till now I have argued that it was the specificity of Arndt’s use of images that promoted a practice of attention and contemplation that can be seen as preparing the ground for what then later in the eighteenth century became crucial aspects of an Enlightenment aesthetics, especially the concern with disinterested interest, a particular kind of pleasure that is different from the gratification of the senses. At this point it is necessary to take a step back and look at the role and function of these spiritual exercises in a larger context, in their effect on the Christian concept of man. On the one hand, Arndt is a loyal Lutheran theologian in that he does not advocate good works. He promotes a notion of religion as primarily being defined by piety and spirituality rather than dogma. On the other hand, Arndt’s effective promotion of the practices that train and enhance the individual believer’s spirituality weakens the position of and necessity for the church and its officials, which include such central aspects of Christianity as the church dispensing the sacrament of communion. Moreover, at a deeper level, the promotion of spiritual exercises as the key practice for becoming a better Christian easily endangers the central tenet of Christian belief, namely its insistence on the fallen nature of man. If self-improvement techniques are the means of becoming a better Christian, the Pelagian heresy, the belief in the fundamental goodness of man, is not far off. And indeed, when already in chapter 2 Arndt turns to the narrative of Absalom’s rebellion against God in order to make the fallen nature of man vivid to everybody he runs the risk of trivializing this fundamental doctrine. Since we can all observe the tendency of children to rebel against even the most loving parents, and since even very young children tend to have tamper tantrums, we are supposed to believe that Adam’s initial act of disobedience has been passed down to all future generations in that tendency to become angry. These examples might make the doctrine of original sin more vivid; however, they also fundamentally weaken it, since one can and must learn to control and manage one’s anger on one’s own.