HOWARD W. BUFFETT

In previous chapters, we outlined the benefits of cross-sector partnerships and important methods and considerations to ensure they succeed. We provided common definitions and discussed the need for comprehensive program planning. We also described human capital coordination across teams, and crucial aspects of collaborative program ownership between funders, implementers, and stakeholders. In chapter 8 we discussed ways for partnership participants to evaluate and select programs cooperatively to ensure that place-based development strategies focus on long-term stakeholder-driven needs. This chapter outlines how partners from across sectors can combine resources into a blended portfolio—with a particular emphasis on philanthropic capital—to finance activities throughout the life cycle of the partnership.

Developing and deploying a blended cross-sector portfolio brings together funding from public, private, and philanthropic partners collaboratively to address challenges that require the coordinated activity of many participants. It focuses the efforts of decentralized teams and leaders across funders, implementers, and stakeholders and drives improved performance toward mutually developed programs and common goals. By including financial market mechanisms, it opens partnerships to for-profit sector knowledge, resources, and expertise that might otherwise be isolated from activities that provide a social good.

The blended cross-sector portfolio approach allows partners to draw from diverse capital pools to affect or offset risk and, in turn, to unlock coinvestment opportunities. This chapter begins with a brief discussion of investment-related risk and then introduces concepts of a blended finance portfolio. We then describe the potential role for philanthropy and detail ten types of philanthropic capital allocations relevant to a cross-sector strategy.

THE ORIGINS OF A PORTFOLIO APPROACH

The 1950s saw the emergence of a new mathematical framework for investors to analyze the trade-off between financial risk and reward. The technique looked beyond an individual investment’s risk/reward profile and focused on the interactions of many investments across asset classes when combined into a diversified portfolio. This approach, modern portfolio theory, suggested that investors analyze and take into account how assets are interrelated rather than consider them in isolation.1 Because assets can share similar volatility, diversifying investments in a portfolio can reduce risk and lead to more predictable or profitable returns.2

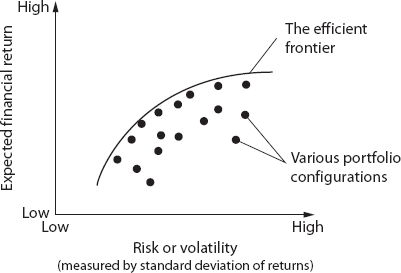

Blending diversified investments to influence the risk/reward profile is central to the theory.3 Investors can analyze groups of investments based on this relationship and select those with the highest levels of return at given levels of risk. Plotting the ideal trade-off points between risk and reward illustrates the efficient frontier—a series of portfolio configurations with optimal investment allocations (figure 10.1).4

Figure 10.1 The efficient frontier illustrates portfolio configurations with optimal trade-offs between financial risk and return. Portfolios falling below the frontier are inefficient or suboptimal; a different configuration of investments could yield higher returns at the same level of risk or could reduce risk without lowering returns (figure is adapted from multiple sources and does not represent actual financial analysis).

Portfolios falling below the efficient frontier are combinations of investments that are suboptimal. If they were configured more efficiently, they could yield higher expected returns at the same level of risk, or the same expected returns at a lower risk.

EXPANDING THE FRONTIER

The efficient frontier as originally conceived focused on the field of traditional finance. It likely did not account for the inclusion of grants or concessionary investments through cross-sector partnerships. For example, consider how public finance, charitable contributions (as first-loss capital), or instruments comprised of philanthropic dollars might change the composition of a portfolio.5 In the context of cross-sector partnerships, could traditional portfolios move beyond a given frontier by blending nontraditional forms of capital into the mix to drive down risk or drive up return?

This question, and the topic of blended finance more broadly, is the subject of a recent joint project between the World Economic Forum and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).6 Called the ReDesigning Development Finance Initiative, this project focuses on increasing the amount and flow of development finance and philanthropic capital to enable private sector investment.7 This blended cross-sector approach is meant to facilitate funding for international economic development in riskier frontier8 and emerging markets.9 The OECD has also made recommendations specific to policymakers for mixing and then mobilizing new forms of capital to these types of markets, and in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal agenda.10 A blended finance portfolio, from this perspective, mitigates risk and supports commercial risk-adjusted returns for private sector partners.11 Similar to the way investors mix assets to reduce risk in their portfolios, blending financial and philanthropic capital attempts to provide analogous results.12

The social value investing framework goes one step further and considers the contribution of philanthropic dollars to a blended cross-sector portfolio as more than a mere subsidy to other investors.13 Funders following this approach actively collaborate with private sector partners, other implementers, and stakeholders in the selection and development of projects. Funders also have a vested interest in the positive social outcomes of the collaboration as it relates to their charitable mission and the long-term viability of the projects in the partnership. From this perspective, funders can leverage private capital to deliver larger projects with greater impact than they could using their dollars alone.

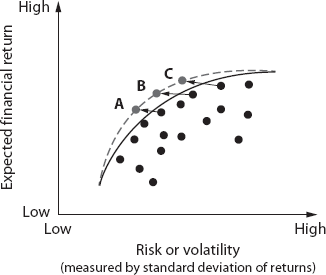

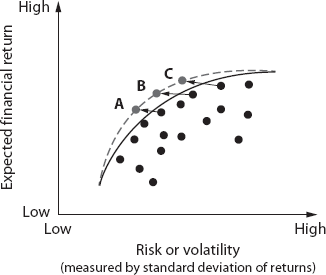

Imagine a scenario in which an investor is considering some set of high-risk investments in small-scale manufacturing in an emerging market. A foundation working in that same region could provide first-loss capital for loans to small enterprises in the same value chain to support the overall business climate.14 It also could partner with local NGOs to provide critical training and education programs so more members of the community are eligible for loans and employment.15 By coordinating activities and goals and blending programs and investments, this type of cross-sector partnership can offset risk or improve returns in ways that traditional finance can not or will not.16 In this scenario, philanthropic capital may have the effect on portfolio configurations marked A, B, and C in figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2 The boundary of the efficient frontier can shift when mixing in concessionary investments by way of cross-sector partnerships. Consider that portfolios may fall beyond a given frontier when blending nontraditional forms of capital into project finance, such as charitable contributions or instruments comprised of philanthropic dollars. This is illustrated by portfolio configurations A, B, and C. The distance and direction of movement for these portfolio configurations is fictitious and for illustrative purposes only (figure is adapted from multiple sources and does not represent actual financial analysis). For a detailed discussion regarding calculations of the efficient frontier, see Robert Merton, “An Analytic Derivation of the Efficient Portfolio Frontier,” Journal of financial and Quantitative Analysis 7, no. 4 (1972): 1851 -1872.

Philanthropic capital held by private foundations stands apart from traditional investment capital in several important ways. First, it is not subject to the same market demands as finance, and it can be invested over very long time horizons.17 This is primarily because philanthropic capital is much more flexible. It can range from entirely concessionary allocations (such as grants), to quasi-concessionary vehicles (such as low-interest loans), to more innovative coinvestments (such as social impact bonds). Philanthropic assets, even if deployed through traditional investment instruments, are unbound by the return-maximizing constraints of the markets. Foundations have no shareholders (by the traditional definition) demanding higher profits and no investors pressuring management to make short-term trade-offs for financial gain.18 Instead, a foundation’s obligation is to its charitable mission and the delivery of social good.

The idea of blending capital through cross-sector partnerships aligns with two key ingredients of the social value investing approach. First, it allows for investment over longer time periods than traditional finance. Second, it enables investors and philanthropists to collaborate in ways that unlock hidden or unrecognized intrinsic value. Philanthropic capital can act as an enabler, supporting local community needs and prosperity, which in turn serves the mission of the foundation. An investor can enter a market it otherwise would not enter, increasing economic activity in the region and linking market activity, while at the same time making a financial return. Combining diverse investment tools blends financial and social goals and bridges gaps in the risk/reward calculus where value would otherwise remain locked away by unresolved constraints.19

In some cases, a blended cross-sector portfolio approach can be straightforward. We saw this in the Comunitas case study with the public-private partnership Juntos Pelo Desenvolvimento Sustentável (Juntos). Private sector leaders and philanthropic donors contributed to the partnership’s general fund by cofinancing projects and services that would improve government processes and reduce bureaucracy. Sometimes outside experts guided planning and program improvements, and the fund partnered with a technology firm to facilitate constituent feedback and input—in line with the people and place elements of social value investing. Once partners settled on program improvements, the government financed the cost of implementing required changes and communicated this to its citizens. These changes improved the social and business climate around local municipalities and made the governments more accountable to constituents. One study found that for every dollar invested the partnership created ten dollars of return through more efficient government services or increased revenue.20

Oftentimes government agencies or municipalities are a primary contributor to a cross-sector blended-capital portfolio. With public financing, all levels of government can play an enabling role, whether through various types of instruments or through changes in regulation. Governments can engage in tax increment financing, provide block grants, offer new market tax credits, or designate business improvement districts, among other things.21 Some government agencies, such as the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, exist to offset business risks for U.S. companies interested in working in emerging markets.22 Although some or all of these methods are suitable in our blended cross-sector portfolio approach, government capital can be far more encumbered than philanthropic capital. Therefore, we are limiting the scope of this chapter to the latter.

HOW PRIVATE AND PHILANTHROPIC CAPITAL MEET

Ultimately, many successful cross-sector partnerships rely on market solutions for long-term success. Some solutions may begin with philanthropic or government grants, but gains for society are more sustainable if these grants catalyze activity supported by a broader economic system. Philanthropic capital can construct the first rungs in a ladder from poverty to prosperity or move social programs from financially infeasible to financially viable, but it cannot complete the journey alone.

For example, philanthropy can provide an impoverished rural community with access to basic resources, training, scientific data, and the supplies necessary to transform barren rural land into productive cropland. As we discussed in the Afghanistan case, local conditions might pose implementation risks and limit prospects for near-term financial return, which would deter private investment. But over time this development might open the door for small-scale food processing and farmer cooperatives. Then the community may gain access to grain marketing and forward contracting. Access to microcredit could provide economies of scale and support more vibrant agribusiness. Eventually this could lead to an environment more conducive to agriculture-related private sector services, such as lending, equipment servicing, and new infrastructure. This is an oversimplification, but many problems remain unsolved for lack of private investment or scaling capital, which relies on market solutions. Using aid or philanthropic funding to offset early stage risk can create opportunities for businesses to support an economic ecosystem and bring in financial products that engage a wide range of potential investors.

Through a blended cross-sector portfolio approach, philanthropists can collaborate with investors using many different types of financial products.23 Early stage capital may focus on advancing the maturity of a project to reach viability, sustaining it until it is large enough for more traditional forms of investment. This type of philanthropic stacking places grants at one end of a range of options, uses different types of reduced-cost lending in middle layers, and finds market-return-seeking products at the other end.24

FINANCIAL TOOLS IN A BLENDED CROSS-SECTOR CAPITAL PORTFOLIO

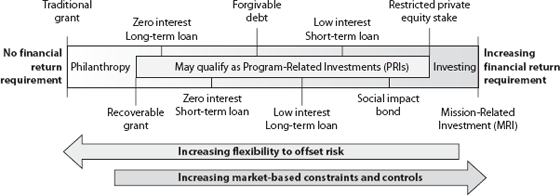

A range of blended portfolio tools is described in this section, and figure 10.3 outlines ten types of capital allocations available to philanthropic organizations. The furthest left end of the range represents allocations with no requirement for financial return or payback. These types of allocations have high overall flexibility and the potential to significantly affect the risk/reward profile of a given project. At the right end of the range are investments with an increasing requirement for financial return and constraints over how the funding can be allocated.25

Figure 10.3 A blended cross-sector portfolio approach may draw from many types of philanthropically oriented financial tools. This chart illustrates ten types of various capital allocations ranging from completely concessionary grants at the left end to more traditional return-seeking investments at the right end.

Traditional Grants

Through traditional grant-making—at the furthest left end of the range—a foundation typically transfers capital to an implementer who completes a project, advancing mutual goals to improve society. This is similar to what we saw in the Comunitas case, where the Juntos program relied extensively on foundations and private donors to finance operations and program services. While grant-making is fairly common, Juntos represents an innovative program design, including funder participation going well beyond just giving a gift. At the city level, grants funded strategic planning in Pelotas, Brazil, for a network of clinics, called Rede Bem Cuidar.26 Partners engaged the community to gather input on how to deliver improved services to meet their needs.27 Grant funding was used to finance project design support by Comunitas staff, rebuild two clinics, and renovate three basic healthcare units. The use of philanthropic capital significantly offset program and implementation risk for the city and provided flexibility for its elected officials to make decisions guided by the community’s input.

In a broad sense, the landscape of traditional grant-making is undergoing change. Until recently, few intentional links between grants and private sector strategies would be found. Typically, uptake into private markets from a grant would be considered an added benefit, not a function of the grant itself. The Afghanistan case, however, contrasts this by illustrating small scale grants that financed market-enabling expenditures.28 As the availability of philanthropic capital has increased generally, and as NGOs become more significant market actors and cross-sector partnerships proliferate, this will continue to shift.29

Program-Related Investments

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service requires private nonoperating foundations to give away, on average, at least 5 percent of their assets to charitable causes every year (or face penalties).30 Foundations generally use the remaining funds to generate profits to grow their assets, leaving considerable resources locked away from charitable activity. Historically, foundations tend to build large financial corpuses. Assets held by all foundations in 2014 in the United States totaled over $865 billion;31 assets held by private nonoperating foundations alone comprised more than 80 percent of that total.32 Generally, foundations think of their assets in a compartmentalized way: 95 percent dedicated to growing assets and 5 percent allocated to grants or charity. Innovative capital allocation strategies (namely, program-related investments and mission-related investments, discussed later) can bridge the two.

As a classification of investment approaches subject to specific eligibility requirements, program-related investments (PRIs) can include many of the financial instruments outlined here. PRIs allow foundations to use dollars from their traditional grant-making allocation to make low-yield investments in support of the foundation’s philanthropic mission. Among other things, this broadens the financial and impact analysis used to allocate the capital and opens interesting cross-sector partnership opportunities.

In 2012, the White House updated its description of PRIs in the U.S. Code as “an investment made by a foundation, which, although it may generate income, is made primarily to accomplish charitable purposes.”33 Accordingly, a foundation can make qualified investments (such as those indicated in figure 10.3) that count toward its minimum 5 percent annual charitable distribution requirements. Furthermore, this class of investments is exempt from a number of taxes imposed on other types of investments made by a foundation. But, as the definition says, the purpose of a PRI must be to serve the foundation’s charitable mission rather than to focus on a potential financial return.34

Pioneering PRIs: Profile of the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation was established in 1936 by Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and his son, Edsel. At one point, the foundation owned nearly 90 percent of the nonvoting shares of the automotive company, making it the largest private foundation in the country.35 By 1968 the Ford Foundation was grappling with how to increase its social reach beyond the limits of its grant-making resources.36 In a proposal to the foundation’s trustees that year, foundation staff urged them to “re-examine the tradition that limits our philanthropy to a single mode—the outright grant.”37 Shortly thereafter, the foundation began its first program-related investments.38 Although not technically classified as such then (the Tax Reform Act of 1969 provided the first legal definition for a PRI39), it focused on programs for minority business development, affordable housing, and environmental preservation.40 The foundation has since allocated about $690 million41 toward PRIs and engages in direct loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees.42

The Ford Foundation has a long record of success with PRIs.43 In 1977, the foundation provided a grant to a new nonprofit lender in Bangladesh for an experimental small-scale credit program.44 This program sought to provide access to credit, mainly to women who had no collateral (such as land), and it organized debtors into small groups with collective responsibility for loan repayment. The model showed promise, reaching fifteen thousand participants with a 98 percent loan repayment rate within a few years. By 1981, the program sought to expand to one hundred thousand borrowers, increasing its partner commercial banks from twenty-five to one hundred.45 The Ford Foundation provided a multiyear recoverable grant for $770,000 as a 10 percent loan default guarantee.46 This guarantee offset the risk of potential loss for new commercial banks interested in joining the program and supported the program’s rapid expansion. Funds from the guarantee that were not needed by the end of the term were to be repaid to the foundation.47 Over time, the foundation increased its support, including financing for a revolving fund for larger enterprises.

Today, this nonprofit lender—Grameen Bank—has more than 2,500 branches and has made over eight million loans totaling more than $20 billion,48 and it pays dividends to its borrowers.49 Structured as a cooperative, Grameen’s borrowers are also the bank’s owners, holding more than 90 percent of the organization. The remainder is owned by the Bangladeshi government.50 In 2006, Grameen Bank and its founder, Muhammad Yunus, were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.51

The number of foundations and the amount of foundation assets available for PRIs has grown considerably since PRIs began in 1969. The MacArthur Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the F. B. Heron Foundation, to name a few, all use PRIs to unlock their assets and increase social good. More recently, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation entered this space.52 It has made more than sixty PRIs, committing more than $1.8 billion in capital with a total allocation of $2 billion to its PRI strategy.53

Recoverable Grants

Recoverable grants are pools of capital allocated to projects that meet the objectives of a funder but are dedicated to catalyzing longer-term for-profit business development.54 Similar to traditional grants, they are given without a requirement for financial return. What makes them “recoverable” is that any profits generated from the grant funding, which (as traditional commercially generated profit) would normally be returned to an investor, are instead put back into a capital pool to make future grants. For example, the nonprofit Echoing Green provides cash stipends to for-profit social entrepreneurs who agree to pay back the stipend if their company becomes successful. If the company fails, then it owes no debt.55

As one of the most risk-tolerant and inexpensive forms of capital available, recoverable grants act as “convertible note[s] with no time expiration and no liquidation payback rights.”56 Because these products are classified as grants, there is no obligation to the grant-maker if the borrower defaults.57

Zero Interest Short-Term Loans / Zero Interest Long-Term Loans

Another way for a foundation to spur market development is by offering zero-interest loans.58 For example, a community garden that is expanding operations may need financing for a new greenhouse and the equipment and supplies to grow more food. A community foundation could provide a long-term, no-cost loan for the greenhouse so that a local community development financial institution (CDFI) would be willing to open a line of credit for seed, fertilizer, and tools.

This type of commitment can encourage private sector lenders to loan to individuals or groups they would otherwise find too risky, and it creates credit histories that can be used for future lending considerations. Zero-interest loans provide a substantial subsidy to a loan offering, and it holds a borrower accountable more than grants or recoverable grants do but less than other financial products.

Forgivable Debt

Forgivable debt is typically a loan structured to incentivize a particular behavior or accomplish a measurable social outcome agreed upon between a philanthropic lender and a borrower.59 Any portion of the loan may be forgiven if specific conditions are met.

For example, a foundation makes a forgivable loan to a social enterprise running an early morning before-school program with the goal of reducing high school truancy. If the program meets a given target—a 20 percent reduction in student absentees within six months—then the foundation would forgive the loan as though it were a grant. If the target is not met, the foundation could recollect the money as a debt.

Low-Interest (Concessionary Rate) Long-Term Loans and Low-Interest Short-Term Loans

In other cases, a lender may offer a loan at a rate that the borrower cannot afford but could pay back at a reduced interest rate.60 In these cases, philanthropy can subsidize the lending rate to a level feasible for the borrower but still profitable for the lender. Sometimes these rates can be adjusted over time, with the subsidy gradually removed as a track record is established, the borrower stabilizes, and the lender becomes more confident that the loan will be repaid at favorable terms.

In the community garden example, imagine that the CDFI is providing both the loan and the line of credit. In this case, a foundation could subsidize the interest rate on the loan and line of credit so that it meets the needs of both organizations.

Social Impact Bonds

Social impact bonds (SIBs) are an innovative financing instrument designed to help governments, foundations, and investors structure prevention programs that achieve social outcomes.61 These outcomes, if realized, save long-term costs that would otherwise be absorbed by society. Therefore, the government agrees to pass some of those savings along to investors who take the risk to fund the programs. But investors are only repaid if the desired outcomes are met.

SIBs are similar to pay-for-performance contracts, through which service providers are paid for results, not for their work to achieve specific outcomes.62 In both cases, providers must closely document success and establish meaningful and measurable outcome indicators.63 For example, a state government agency may want to reduce the number of people receiving compensation through unemployment insurance. Through a pay-for-performance contract, that agency agrees to pay a job training and placement company $5,000 for every person (otherwise on unemployment benefits) they place in a job at a living wage for six months or longer. If the company does not achieve the outcome, they are not reimbursed for their program expenses.

With SIBs, an investor underwrites the cost of a program through a project manager responsible for coordinating the activities. Payment for success goes from the government through the manager to the investors. This payment can include a return on investment, depending on the success of the program. If the program fails, the investors can lose their capital. As a result, the entire up-front investment is at risk because there is no guaranteed payment.64 So far, as the Rikers Island example shows, SIBs have had a mixed track record.

Lessons to Learn: Rikers Island Social Impact Bond

In 2012, a coalition of partners launched the first SIB in the United States. It was designed to reduce recidivism of teenagers released from Rikers Island jail in New York. Financed by a $9.6 million loan from Goldman Sachs (insured by a $7.2 million guarantee from Bloomberg Philanthropies), the program delivered cognitive behavioral therapy from the Osborne Association to teenage inmates.65 MDRC, a nonprofit research center, was the intermediary managing organization, and the Vera Institute of Justice served as an independent evaluator. In the arrangement, Goldman Sachs would be repaid only if the existing recidivism rate of 50 percent was reduced by 8.5 percent, and they would receive a profit of up to $2.1 million if the reduction exceeded 10 percent.66

The program encountered a series of operational and contractual challenges, including control group problems and staffing shortfalls.67 In July 2015, the Vera Institute concluded that the program did not reduce recidivism for the 2013 program participants during the twelve months following their release from Rikers, as compared to a historical control group who passed through the jail before the program began.68

How much value the program ultimately provided, regardless of its cancellation, depends on who you ask.69 Supporters argue it was worthwhile for what they learned using an experimental approach. Supporters also point out that the experiment was paid for by investors, not taxpayers,70 and implementers of the program can document participants who say it helped them stay out of jail.

Bringing a private partner into government social programs can yield efficiency and innovation, and having government as a partner creates opportunities to scale successful experiments more easily. But bringing these two groups together in such a collaboration requires an independent evaluator, especially because financial payment is conditioned on mutually agreed goals. Involving the philanthropic sector diffuses the risk and encourages partners to expand programs if they succeed.

Detractors of the Rikers Island SIB, however, suspect that city officials spent a lot of taxpayer-subsidized time on the project. They also wonder whether the time horizon for investor payouts over a long-term program would have been prohibitive for investors, even if the experiment had run successfully. The same holds true for the payer: significant savings for the government may not occur until, for example, recidivism is dramatically reduced.

Furthermore, SIBs could pressure government to privatize activities that may not benefit from being privatized—prisons are an example. The high transaction costs of adding a managing intermediary, an outside evaluator, and an outside operator may doom some SIBs to failure. Even when successful, SIBs may be too complicated to easily replicate or scale. Finally, critics point to opportunity costs—philanthropic dollars are not unlimited, and they claim spending them on speculative experiments could be wasteful.71 We believe this type of experimentation is a sweet spot for philanthropic dollars, and regardless of these challenges, SIBs are not likely to go away soon.72

The very first SIB is a recent success story. The Peterborough Pilot Social Impact Bond in the UK ran from 2010 to 2015 and had positive results.73 Similar in goals to the Rikers Island SIB, the Peterborough SIB was designed to reduce the number of prison reoffenders. Of a first cohort population of roughly a thousand participants, the SIB-financed program reduced the reoffending rate by 8.4 percent compared to the control group.74 An analysis from the results of a second cohort estimated an improved reduction rate of 9.7 percent.75 These results averaged above the minimum threshold required for success (a 7.5 percent reduction), and the SIB’s outcome payment to investors was triggered.76

Since this first SIB launched in 2010, over one hundred others have begun, with at least seventy more under development.77 SIBs are under way around the world: in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, among others.78 A social impact bond is inherently structured as a cross-sector partnership. According to an OECD study on SIBs, “the combination of partners is part of the innovation.”79 Although still a developing model, the goals and intentions of SIBs embody many of the characteristics of the social value investing framework.80

Restricted Private Equity Stake

In 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department updated and clarified their list of permissible PRI-related activities.81 As a result, foundations were given more clarity on the use of PRIs for making equity investments in for-profit companies if those investments serve a social purpose (assuming certain conditions are met).82 For example, the Gates Foundation took an equity stake in a biotech start-up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Among other things, it encouraged the company to apply its new and pioneering T-cell targeting discovery technology toward the creation of a vaccine against malaria—a major focus of the foundation’s global health strategy.83

Although not a requirement, the IRS indicated that exit triggers automatically liquidating a foundation’s stake in a company, once the company turned profitable, could substantiate the charitable claim of the investment.84 Furthermore, such equity investments may be combined with grants or loans (from the same foundation or otherwise), enhancing the charitable objectives of the investment even further.85

Mission-Related Investments

In very simple terms, mission-related investments (MRIs) complement PRIs by picking up where they leave off.86 An MRI strategy either supports social goals (such as actively seeking investments that contribute to a foundation’s overall charitable purpose) or avoids contradicting the values or mission of a foundation. However, investments in an MRI portfolio fall outside the scope of PRIs, in part because these investments are intended to generate a market-rate financial return, and because they come from the corpus of the foundation, not the grant-making side.87 For example, a foundation focused on environmental preservation or air quality could use its corpus to make a significant investment in a large, for-profit solar energy project. Unlike PRIs, a foundation cannot count MRIs toward its 5 percent annual charitable distribution requirement. Although mission-related investments are not a separate legal classification on their own, they must still follow IRS non-jeopardizing rules.88 Similar to traditional investments, MRIs may be subject to unrelated taxable income (whereas PRIs are not).89

An investment strategy led by MRIs is very different from a passive or blind investment strategy, which could have a foundation’s endowment investing in companies that are diametrically opposed to its charitable mission. Continuing with the environmentally focused foundation example, that same foundation could have holdings in a coal or oil company under a blind or agnostic investment approach. Therefore, a foundation may use negative screening to avoid broad investment categories antithetical to their charitable mission or values (such as screening out investments in weapons or tobacco). Or it may choose to engage in or support specific company or industry divestment. For example, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (established by descendants of John D. Rockefeller and financed by the family’s success in the oil industry) announced in 2014 that it would divest its endowment’s assets from fossil fuels.90 Shortly thereafter, the fund also signed onto the United Nations–sponsored Principles for Responsible Investment,91 a voluntary agreement among investors to track and consider environmental, social, and governance metrics in their investment strategies.92

The Ford Foundation took a bold step in 2017 when it announced it would allocate up to $1 billion of its endowment, roughly 8 percent, to an active MRI strategy.93 This was the largest MRI commitment ever for a private foundation, and it is initially focused on “affordable housing in the United States and access to financial services in emerging markets.”94 It is likely we will see more and more foundations making similarly significant commitments in the future.

ADVANTAGES OF A BLENDED CROSS-SECTOR CAPITAL PORTFOLIO

A blended cross-sector capital portfolio uses innovative and flexible funding, such as philanthropic dollars, to shift the risk frontier for projects in a partnership. It is a critical enabler for other elements in the social value investing framework because it unlocks partnership opportunities with high intrinsic social value, and because it also allows partners to focus on outcomes over a long time horizon. As a result, blending investments for social and financial goals has inherent advantages for everyone involved.

■ It widens the risk/reward profile for investors. By blending philanthropic and financial products with differing risk appetites and reward requirements, investors can tap into diverse capital pools for financing partnerships that serve the public good.95

■ It leverages collective assets. By adjusting the risk/reward horizon, initiatives can bring together new coalitions of public, private, and philanthropic partners. Using an effective and collaborative partnership process enables collective capital to solve problems that cannot be addressed by any single sector or class of funding.96

■ It builds a coalition of people. By tapping into a broader alliance of participants, the initiative can access an expanded, decentralized network of leaders, experts, teams, and organizations spanning multiple geographic areas and providing for complementary capital allocation needs.97

■ It aligns financial and social outcomes. By integrating traditional finance, social programs can draw from for-profit sector knowledge, experience, and resources to improve the efficacy of grants or charitable activity. These advantages may not typically be available to such programs, which makes this an important approach for partnerships involved in the development of place-based strategies.98

Partnerships and projects of all sizes can benefit from a blended-capital portfolio. Long-term systems-based solutions, in particular, require significant and diverse capital to finance program expenditures, infrastructure, and services. By engaging an array of capital types, partnerships can provide new solutions or accomplish collectively what would otherwise be impossible individually. This is especially important in parts of the world that face chronic poverty, conflict, or economic downturns, as we saw in the Juntos case. In places where government aid or market forces alone have not built prosperity for communities, or even whole countries, innovative financing through cross-sector collaboration is an exceedingly important strategy.