The Kircherian collection acquainted audiences with uncertainty and exposed the fallibility of their senses even as it displayed a universe that was difficult, perhaps impossible to understand completely. These same principles also shaped a series of important natural philosophical texts written by Kircher over more than twenty years. These works presented their audiences with images and descriptions of phenomena that encouraged a movement between the exercise of the eyes and the exercise of the mind in a fashion that resembles nothing so much as a kind of meditation. Niccolò Cabeo had juxtaposed image and text so as to foster a many-layered understanding of the magnet, doing so within the self-conscious confines of the neo-Aristotelian textbook. Kircher, by contrast, labored under no such confines in his own texts, which were exuberantly syncretic attempts to connect together any number of disparate things: Nature and Art, seen and unseen, known and unknown. While his museum in the Collegio Romano used spectacle and artifice to expose the hidden foundations of nature, in these works Kircher depended upon images and emblems to accomplish the same goal.

This chapter explores three of Kircher’s texts: the Magnes; sive, De arte magnetica (1641), the Ars magna lucis et umbrae (1646), and the Mundus subterraneus (1664). Together, they span the better part of his intellectual flourishing, but more importantly, these three texts exemplify Kircher’s obsession with unlocking and revealing the secrets of nature. Each was concerned with questions about seeing and, specifically, “how to see”—either how best to apprehend and study insensible phenomena such as the magnetic force or the subterranean realm, or the physics and psychology that supported the acts of seeing and knowing. In each case, Kircher chose subjects broad enough that their examination required multiple approaches; in some cases, he depended upon the authority of the ancients or the unsubstantiated reports of popular belief, while in others he resorted to the rigors of experimentation and the careful testimony of reliable witnesses. Often, he brought most or all of these approaches to bear on individual phenomena. This fluidity of interpretation and methodology can make Kircher’s works difficult to decipher. Unlike Cabeo’s Philosophia magnetica, one cannot classify Kircher’s writings as belonging to any particular camp; they demonstrate a fierce eclecticism that is typical of almost everything he attempted.

These texts were also linked together by their attention to both the perils of uncertainty and the tools Kircher proposed to mitigate or dispel altogether that same uncertainty: elaborate methodologies with which his readers could witness and understand the invisible, connective power of the magnet or the deepest recesses of the Earth. In his museum, these methodologies revolved around the intervention of artifice and its concomitant rhetoric of imitation or similitude. Kircher also repeated this theme in his published works, which he filled with images and descriptions of the very machines on display in his collection, but the way in which he also used pictorial representations transformed these works into texts as grandiose and beautiful as any meditative work commissioned by the Society of Jesus. Indeed, it is as meditative compendia that we should understand Kircher’s published works: deliberate and self-conscious attempts to connect the eyes and minds of his audience with both the unseen foundations of the universe and the providential design of its Creator.

In the Magnes; sive, De arte magnetica of 1641, Kircher waxed lyrical about the invisible power of the magnet, seeing in the humble lodestone the key to the structure of the cosmos. His text makes for a fascinating counterpoint to the magnetic machines that formed the heart of his collection in Rome: those machines instructed their audiences in how to visualize the insensible correspondences that drove the universe, but the Magnes sketched those correspondences in full, using imagery and emblems to do so, becoming finally a grand meditative exercise that sought to connect together the world, humanity, and God. Thereby was the promise of the Kircherian machines realized in full.

Published only five years after the Magnes, the Ars magna lucis et umbrae, or “The Great Art of Light and Shadow,” delved more closely into the particulars of knowing. Easily as ambitious in scope as the Magnes, the Ars magna addressed both the utility and the deceit of the eye. Therein, Kircher made clear that he would not pursue the empirical certainty demanded by conventional Aristotelianism, and once again he emphasized the importance of artifice in the acquisition of knowledge. As the magnetic machines illustrated in the Magnes became instruments of revelation, the science of optics, as reified in the microscope, the telescope, and varied catoptrical devices, became the means simultaneously of bemusing and enlightening the mind.

Arguably one of the greatest of Kircher’s later works, the Mundus subterraneus or “The Subterranean World” built upon the themes expressed in these earlier texts. It presented the depths of the world as shadowed and mysterious, inaccessible save through the intervention of artifice (which imitated subterranean processes and thereby exposed them to observation) or the studied contemplation of images (by which Kircher sought to encourage his readers to descend into the Earth and “see” its depths for themselves). It was here that Kircher most explicitly presented his audiences with a probabilistic vision of the world: not as it was, but as it might be.

Together, these works spanned some twenty-five years of Kircher’s life, but the general epistemology they presented remained coherent and unified throughout. In every case, Kircher emphasized the utility of artifice in revealing the hidden operations of nature while fostering a self-conscious syncretism that sought to connect together the disparate parts of the world into a coherent, comprehensible whole. At the same time, however, he moved quietly but clearly away from the fundamental tenets of Aristotelianism, openly questioning the pursuit of demonstrative certainty before abandoning it in favor of a more subjective, almost meditative experience in which text, image, and the mind all collaborated in the acquisition of knowledge.

Giorgio de Sepi described the magnet as the medulla or centerpiece of the Kircherian collection in Rome, and the magnet’s invisible power drove some of Kircher’s most elaborate and puzzling displays. It is unsurprising, then, that he should have published no less than three separate works devoted to magnetism. The first, his Ars magnesia, appeared in 1631 and is generally considered to be Kircher’s first published work. The Regnum naturae magneticum appeared in 1667, proclaiming on its frontispiece, Arcanis nodis ligatur mundus—“The world is bound by secret knots,” perhaps one of Kircher’s best-known maxims. But it is his middle work on the magnet, the Magnes; sive, De arte magnetica, that will occupy our attention here. It was Kircher’s greatest work on the subject, appearing first in 1641 and going through two subsequent editions in 1643 and 1654.

Kircher cast the magnet as the greatest exemplar of nature’s hidden secrets in his museum, and he echoed this throughout the pages of the Magnes. With a nod to the dramatic, he opened this work with numerous allusions to shadows and darkness.1 Characterizing his own quest for a means of describing and demonstrating the activity of the magnet in such terms not only permitted Kircher to underscore its difficulty and the general state of ignorance that prevailed concerning this most pre-eminent of nature’s mysteries, but also forged a link with Cabeo’s earlier rhetoric in the Philosophia magnetica, in which the Italian Jesuit had characterized his own work as an illumination of shadows. In fact, there are numerous parallels between Kircher’s Magnes and Cabeo’s Philosophia, and Kircher was quick to praise Cabeo as one of “those others who are not without glory in this Herculean labor” and who had corrected the errors found in the work of “the Englishman Gilbert.”2

From the start, then, Kircher encouraged his audience to view the work that followed as a kind of revelation, a lifting of shadows. From this grandiose beginning, however, his prose fell into a rather dry recitation of the magnetic nature, a description of various aspects and “faculties” of the magnet itself—for example, that its force extends outwards in a sphere, that it propagates its force in straight lines, and that its natural motion is circular, all claims made previously by Cabeo. Kircher also echoed Cabeo in his assertion that the Earth’s magnetic attraction to the celestial poles made it incapable of motion, explaining that God had providentially designed it thus so as to balance and preserve both climate and life on the terrestrial surface: were either the Earth or poles to “fluctuate” or change, chaos would result, and those animals and plants created to thrive in one climate would suffer in another.3

The first section of the Magnes, introductory in nature, not only established the basic nature of the magnet but also linked the magnet with other natural phenomena, particularly light. It was precisely the kind of description that Cabeo had advanced in 1629, and thus bears the hallmarks of Peripatetic arguments concerned with the propagation of species or qualities. Kircher pointed out that both the magnet and light diffused their respective qualities through a passive medium, and that in doing so they would not be altered “too much” by the medium itself but would themselves induce a “certain and determined alteration” in a receptive body.4 Moreover, while the propagation of light could be stopped by “neither cold, nor heat, nor glassy bodies, nor water, nor the hardest crystal”—only opacity was “inimical” to light, preventing its further propagation—the magnet’s propagation of quality was more powerful still, unaffected by the interposition of objects that were “heated, or cooled, or dense, or rare, or opaque, or translucent,” leading Kircher to suggest that the magnet could diffuse a quality out from itself with a force that was almost spiritual in nature—“spiritual,” that is, in the sense that material obstacles could not impede this propagation of quality.5

There is little in the first book of the Magnes that can be considered original to Kircher. At the same time, however, it is by far the shortest of the three books that together comprise the Magnes, a fact that speaks eloquently to the priorities that guided Kircher in the production of this text. This basic explanation of the magnetic nature, certainly the most blatantly “natural philosophical” material in the Magnes and the only content that one might deem properly Peripatetic, was of relatively little importance in the larger scheme of the work that Kircher envisioned. This suggests that the questions he sought to answer were primarily not those we might expect of a “proper” experimentalist, nor of a Peripatetic naturalist. This may explain why many, including biographers of Kircher, have struggled to characterize his work as something more than a collection of oddities, but it also points us towards the true subject of Kircher’s Magnes. It was a two-fold endeavor: firstly, the consideration of an invisible and pervasive unity that was portrayed emblematically by the magnet, and secondly, an outline of the methodological and epistemological means of examining and comprehending that unity. As in his museum, Kircher used the Magnes to celebrate the insensible, but he also provided his readers with clues as to how to study it.

The next section of the Magnes was not a dry recitation of philosophical facts but an exuberant and, at times, implausible disquisition on applied magnetism. This second book of the Magnes was entitled, “On the magnetic art, or the magnet applied,” and an early modern thinker might have considered it an extended rumination on the possibilities of natural and artificial magic—that is, the manipulation of unseen forces in the production of specific effects. Indeed, Kircher used the term “natural magic” to describe some of the elaborate magnetic machines he envisioned—the heading of one section was “Magia Naturalis Magnetica”—and so it is unsurprising that it was here that the first depictions of Kircher’s wondrous magnetic machines appeared, some of which also took center-stage in his early collection. Thus, he first articulated in 1641 many of the messages later embodied in his museum, as Kircher ruminated on the possibilities presented by the artificial demonstration of the magnetic force. The engraved illustrations that fill this part of the Magnes evince a richness and detail that stand in sharp contrast to the much simpler woodcut renderings included in the first book, another clue to the priorities at work in this text. That Kircher went to the effort and expense of commissioning so many detailed illustrations, many of them technical in nature and thus requiring still greater levels of attention in their production, suggests that Kircher saw these particular illustrations as critically important in the overall scheme of his Magnes. Indeed, devoted as this work was to the construction of a magnetic art, one could argue that these technical and practical illustrations did form a crucial focus for Kircher’s endeavor.

Most of the copper engravings in the Magnes depicted instruments that were designed to exploit the pervasive and invisible power of the magnet, though two such illustrations employed moving parts that the interested reader could cut out and then assemble to create actual instruments within the text itself.6 Other illustrations depicted merely the face of a theoretical device or magnetically-driven machine, demonstrating the portion of the instrument that would be used, for example, to calculate time or map the movement of the heavens.7 Some engravings also purported to demonstrate the actual mechanism required to construct particular machines such as a magnetic clock, complete with a cutaway view of the clock’s base and the gears within. These illustrations were practical in nature, functioning both as instruments in and of themselves and as guides to the ingenious reader who desired to comprehend or even construct these wondrous magnetic machines.

Another such illustration highlighted the utilitarian and spectacular (as opposed to philosophical) emphasis that lay behind Kircher’s interest in the magnet. We might recall that De Sepi mentioned a statue that moved “by its own will” in the Kircherian collection, and which the Magnes revealed to be Daedalus.8 In discussing this self-moving statue, Kircher included an illustration that depicted Daedalus frozen in the act of moving, standing in the centre of a stage framed by a vast archway and a solid backdrop, both covered with dozens of mirrors. The text that accompanied this illustration described the purpose of this particular demonstration: “Catoptrica Magnetica; in which, by a certain disposition of mirrors, reflected and multiplied images exhibit diverse and joyous spectacles of things by means of magnetic motion.”9 Note the use of the term “spectacles”—the moving statue, like the rest of the wondrous magnetic devices and machines that Kircher described, presented in its own activity a spectacle of the magnetic force, a means of seeing or witnessing that force at work. Note, too, what Kircher proposed to exhibit with his multitude of mirrors: not the hidden mysteries of the magnet, but the veracity of the magnet’s mysterious efficacy. In other words, what Kircher displayed was not the occult causes of magnetism but an altogether different thing: the wondrous nature and uses of the magnetic force. This was also what the magnetic machines on display in the Kircherian collection offered to their audiences: they did not necessarily enlighten their audiences as to the philosophical causes behind the spectacles they presented but, rather, highlighted the mysterious and pervasive power of the insensible correspondences that webbed the cosmos.

While the second book of the Magnes detailed the application of magnetism to the production of particular effects and displayed in the workings of these machines the unseen correspondences that pervaded the universe, the third and final book examined these correspondences themselves. It was here that Kircher explored his emblematic worldview, its basic principles made clear in the title, “The magnetic world, or magnetic chains.” This notion of chains was to become a central and symbolic expression, and Kircher promised in the opening pages of the third book to discuss “the magnetic binding of all natural things.”10 This third book of the Magnes is the longest by far, suggesting that it was here, in this discussion of “the binding of all natural things,” that Kircher focused most of his attention.

The magnet, with its ability to influence distant objects by means of a hidden power or force, operated for Kircher as a reification of the invisible bindings between natural objects. His worldview consequently depended upon the occult to a significant degree, for the invisible and intangible nature of these correspondences confirmed for him their divine provenance. At the same time, however, the Magnes demonstrated an obvious desire on Kircher’s part to render manifest the unseen, a feat that he accomplished in two distinct but related ways. The first, which was spectacle, we have already encountered: the myriad machines and devices illustrated and described in the Magnes (and made real in the Kircherian museum) demonstrated the wondrous uses and effects of magnetism, making these things tangible to their audience. The second way in which Kircher rendered manifest and tangible the unseen links between things, however, lay in the realm of emblematics, which portrayed in visual form the unseen magnetic correspondences between natural objects as chains and knots.

Though the magnet was the ostensible subject of Kircher’s work in the Magnes, in the third and final book he quickly moved beyond the magnet itself when he started to discuss a wider system of linkages between natural things. To his own question, “What is the key of nature?” Kircher responded, “There is one key to nature, a singular thing, that sets forth unity in dissimilar materials.”11 This “singular thing” was a form of magnetism, though one that operated between any number of objects rather than merely between the lodestone and iron, and its ability to create unity from disparity occupied a position of crucial importance in Kircher’s worldview. His notion of a pervasive system of linkages between things also dovetailed with his claim that “consensus and dissension” were the two primary forces that drove the universe, possibly an homage to the classical Empedoclean forces of Love and Strife.12 Examples included the movements of the planets (about which he disagreed with Johannes Kepler, who had invoked a kind of magnetism to explain his heliocentric cosmological system13) and meteorological phenomena, as well as the magnetic links between the elements that permitted the ingenious wonder-worker to change one into the other using a series of machines—for example, turning water into air, or air into fire.14 Kircher also addressed a number of interesting questions such as “whether light is drawn magnetically” to the Bolognian Stone, one of the only phosphorescent substances then known,15 and argued that the tides were the result of complex magnetic forces acting between the sun, the moon, and the oceans.16

As he proceeded through this final section of the Magnes, Kircher ascended to ever-greater heights of rhetorical showmanship, culminating in a long disquisition on the metaphysical dimensions of magnetism. Having exhausted his store of physical phenomena, he turned to the subject of love, the ultimate consensus between subjects that brought the disparate into harmony, devoting a lengthy section to “the wonderful power and energy of love.”17 Kircher insisted not only that love was present in all things, but that it was also “the author and conservator of all things” and that “all arts and sciences are produced from love.”18 Attaching these claims to a comprehensive and informative list of the “symptoms of love,”19 Kircher drew a conflation between love and magnetism: both existed within all things, and both seemed to drive the forces of “consensus and dissension” so central to Kircher’s worldview.

Immediately following this discussion of love, audiences reached the end of the Magnes and a final epilogue: “Magnes Epilogus, id est, Deus Opt. Max.” Kircher announced here that “there is a force connecting all things, which is the Holy Spirit,”20 and went on to discuss the chains that bind our minds to God as well as to the world.21 In many respects, this is the most important part of the Magnes, the culmination of everything that has come before: the final word and, indeed, the final goal of Kircher’s treatise, demonstrating that we are linked to God. These links, present in the natural world yet also joining us to God, mind to mind, soul to spirit, were, for Kircher, the ultimate justification for why the magnet deserved scrutiny. Magnetism, consensus, love, the Holy Spirit—however he chose to characterize this binding force, Kircher made it clear that they were all one and the same thing, a power that was everywhere and linked everything. We may witness it most directly, most easily, in the simple object that is the magnet, but the power that draws a piece of iron to a lodestone is no different in kind from the forces that govern the universe and everything in it.

The epilogue of the Magnes casts the rest of the work in a spiritual light, a key point if we are to understand the connections between Kircher’s emblematic worldview, his insistence on rendering these chains visible and knowable, and the wider mission of the Society of Jesus, which was founded on a commitment to finding God in all things. With this epilogue, Kircher turned the Magnes itself into a kind of spiritual journey, from the dry and brief discussion of the magnet’s properties at the beginning to this mystical and theological apex at the very end. The journey between these points included a series of successive revelations, first of the properties of the magnet’s power, then of the myriad uses of that power, and then of the place of that power in the wider system of the world. Indeed, those who read this epilogue were experiencing another kind of revelation, spiritual in nature. In an important sense, this epilogue shows us that Kircher sought to use his Magnes to train his readers in the same kind of contemplative exercise that was central to the formation of the early modern Jesuit; through observation, imagination, and contemplation of the humble lodestone we are meant to apprehend not just God, but also His ties to the natural world. There is a theological project here as well as a philosophical one.

In its entirety, the Magnes provided readers with a vision of the insensible parts of the world—or, more particularly, a vision of the insensible links that webbed the cosmos. The entire text functioned as a sort of map, laying out where one might find these correspondences and how one might best “see” them in action. One finds in the Magnes a work that was highly ordered, leading its readers carefully (if, perhaps, ponderously) towards an understanding of universal unity and the respective places within this web of correspondences of natural objects like the magnet, the inquiring mind of the naturalist, and the ever-present hand of God.

Kircher not only alluded rhetorically in his Magnes to the invisible correspondences that pervaded the universe, but also displayed them visually as well in the form of elaborate emblematics. Emblematic representations are usually built upon a framework of links and correspondences where one thing symbolizes or represents something else entirely.22 In the Magnes, emblematics were not intended to represent faithfully or literally any particular properties of the magnet, but instead to depict the place of the magnet within the wider universe. Kircher’s willingness to use this model of representation was rooted in how this model had already been used within the Society: namely, as a means of both representation and dissemination. Alongside the images found in much of the formative meditative literature circulating within the Society was a complementary tradition that favored the use of the classically-inspired emblem as a representational tool, reaching its zenith with the publication of the Imago primi saeculi Societatis Jesu of 1640. The importance of emblematics to Jesuit pedagogy and publicity was also closely tied up with notions of spectacle: the lavish plays and performances staged in Jesuit colleges drew heavily upon emblematic associations.23 Thus, the fact that Kircher drew on an emblematic worldview in his efforts to showcase the powers of the magnet is unsurprising. His commitment to this form of symbolic hermeneutics recalled both the earlier writings of Renaissance naturalists and the thriving emblematic tradition that reached its height within the Society in the decades prior to the publication of Kircher’s work on the magnet.

As Cabeo had earlier gone about attempting to make visible the occult force of the magnet through a series of visual and rhetorical tools, so too did Kircher choose to represent the invisible visually in a grand emblematic frontispiece that appeared in his Magnes. Before the third edition, however, this emblematic image was only the frontispiece to the third and final book of the treatise.24 Until then, the frontispiece of the 1641 and 1643 editions functioned more as an explicit dedication to Ferdinand III and the Hapsburg monarchy, with the double-headed Hapsburg eagle surmounted by the imperial crown and clutching in its claws three lesser crowns and three scepters, all linked magnetically, one to the other. The motto that curled around the legs of the eagle read, “Et Boreae et Austri Acus,” a play on words that linked the compass, “the needle of both north and south,” with the house of Austria, “Austri-acus.” When the frontispiece to the final volume of the Magnes became the frontispiece for the entire work in 1654, however, the dedication to Ferdinand IV all but disappeared, lost amidst the profusion of images. A new, central motto now overshadowed the Hapsburg dynasty, both figuratively and literally: Omnia nodis arcanis connexa quiescunt, “All things rest connected by secret knots.” Though we cannot know for certain whether Kircher himself chose to employ this particular representation as the frontispiece of the entire Magnes by its third edition, this emblematic scene expresses more faithfully the conceptual foundations of the Magnes than did the previous paean to the Hapsburgs.

Figure 5.1 The Hapsburg-themed frontispiece of the Magnes; sive, De arte magnetica, 2nd ed. (1643).

Source: Courtesy Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

The new frontispiece to the Magnes portrayed a vast schema in which “magnetic chains” not only bind together the entirety of human art and learning but also link the microcosm of humanity, the sublunary world, and the celestial realm with the “archetypal world,” the world of God as Creator. This theme of connections and linkages is repeated throughout; in the background, we move from the roots of trees burrowing into the ground to the cloudy heavens overhead, these two realms of the terrestrial and celestial linked by the complex arrangement of chains and discs that overlays this natural backdrop. Fourteen human arts are represented and named, with theology pre-eminent at the very top of the schema, flanked by philosophy and medicine, and followed then by natural magic, arithmetic, geography, music, astronomy, optics, mechanics, cosmography, rhetoric, poetry, and physics. Each of these is linked in turn to the central discs symbolizing the three main divisions of the cosmos—sublunary or terrestrial, superlunary or celestial, and the human microcosm—which surround, but are not actually linked to, the mundus archetypus, the archetypal world symbolized here by the radiant eye of God situated in the center of two triangles. What Kircher produced in this emblematic schema was a figurative map of the Magnes itself: the links between the arts and sciences exemplified in the investigation and utilization of magnetism, and the application of these arts and sciences to the subsequent investigation of the correspondences between the macrocosm, the microcosm, and the divine.

Kircher chose to represent the invisible magnetic force emblematically as chains, a theme that he repeated both in the frontispiece to the earlier editions of the Magnes and in the frontispiece to the later Regnum naturae magneticum, which appeared in 1667. In every case, these chains exemplified the links that Kircher believed to pervade the cosmos. Their ability to bind one thing to another was emblematic not only of the activity of the magnet itself, but also of the wider correspondences that one could follow from natural things directly to God. This account was one level on which Kircher displayed the power and activity of the magnet, using a symbolic hermeneutics to clarify for the reader the role of the magnet in the wider cosmos.

Figure 5.2 “All things rest connected by secret knots”: an emblematic schema representing the connective power of Kircher’s unseen correspondences.

Source: Courtesy Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

That Kircher not only employed actual printed emblematics in his attempts to represent magnetism, but also constructed an entire emblematic worldview centered on the magnet itself, allowed him to portray and exhibit the magnet’s occult force without diminishing its value as an example of invisible correspondences in the natural world. This approach was not the same as Cabeo’s insistence on exposing and illuminating the secrets of the magnet. Kircher appealed to different visual strategies: on the one hand, concrete representations designed to demonstrate only the effects of magnetism, and on the other, an emblematic representation that privileged the hidden nature of the magnet itself by portraying magnetism in an abstract, symbolic fashion.

Thus, what was important for Kircher was not the precise rendering of these magnetic chains, but rather their manifestation in a fashion that would permit the viewer to comprehend (and marvel at) the unity binding together all of Creation. From Kircher’s use of emblematics, both as a model for the ties between disparate objects and as a means of representing visually his scheme for a world linked by secret knots, to his subtle and skillful use of spectacle as an effective means of making apparent to his audience the presence and power of these correspondences, we are confronted in the Magnes with an attempt to draw back the curtain and expose to view a system of linkages or, more precisely, a universal unity that, though shaped and mediated by invisible chains, could be revealed and demonstrated. This was Kircher’s attempt to capture, as best he could, the harmony and unity of Creation and present to his audience a series of images, emblems, and spectacles that converted the invisible to the visible while simultaneously serving as a kind of religious devotion, confirming God’s presence at the center of this harmony and unity, and encouraging readers to revere that presence.

Kircher preserved the magnet as a symbol of the occult in nature, allowing this exemplar of the invisible to express in visible and manifest terms the correspondences that Kircher himself perceived between all things. Cabeo, by contrast, had turned to a series of iconic and illustrative representations in his efforts to open the magnet’s hidden properties to view; for Cabeo, the issue at stake was the revelation of a hidden thing. Indeed, these differences between the respective programs of Cabeo and Kircher are obvious even in the titles of the works in question. Cabeo produced a work devoted to a magnetic philosophy, an endeavor that required the exposure of the magnet’s innermost principles through Peripatetic reasoning and the establishment of the magnet’s intelligibility as a natural object. His rhetoric of seeing and vision was both tied to the empirical foundations of Aristotelianism and encouraged by the “figures and pictures” added to enhance the text, suggesting that the usefulness of those images lay not necessarily in the knowledge they directly conveyed but rather in their mediation between seeing with the eyes and understanding with the rational mind. His diagrams and demonstrations were fundamentally illustrative and iconic in nature, and so did not need to be technical or precise.

Kircher, on the other hand, produced a treatise on the magnetic art, an enterprise fundamentally different from Cabeo’s philosophical work. For Kircher, the importance of the magnet lay in the potential uses of its properties and in its reification of the unseen correspondences that webbed the universe. Whereas the “figures and pictures” produced by Cabeo functioned as devices of revelation that simultaneously represented an aspect of the magnet’s hidden power and exercised the eyes in the service of philosophical understanding, the highly detailed and technical diagrams included in Kircher’s Magnes functioned instead as a guide for the practical philosopher, as blueprints for the manufacture of machines, and as illustrations of the varied applications of the magnetic art. The majority of his diagrams and demonstrations were illustrative, but also encouraged the reader to witness and experience the power of magnetism for himself.

In a letter to John Pell in 1646, Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673) remarked of Kircher’s most recent work, “I saw lately a book of the Jesuit Kircher, on light and shadow; it has so many fine figures in it, that I suspect it has no great matter in it.”25 Her disdain, however, was misplaced; Kircher’s Ars magna lucis et umbrae, or “The Great Art of Light and Shadow,” was a far more ambitious work than the Magnes. Published in 1646, its scope was vast: Kircher himself declared in its opening pages that its domain encompassed the entire universe, for everything possessed combinations of Light and Shadow.26 Its central preoccupation with these two things permitted the Ars magna to become a powerful commentary on both seeing and knowing. Buried within its nearly one thousand pages are indications that Kircher fashioned an epistemology that veered away from Peripateticism in its attempts to accommodate the mingled necessity and fallibility of the senses. The Ars magna was in fact an extended disquisition on the fundamentals of knowing: not merely the action of the eye, but its deception as well. This text, perhaps more than any other that Kircher produced, sought to explore and expose the fundamentals of knowing. Its contents ranged from sardonic disquisitions on Peripatetic logic to praise for the utility of spectacle, from celebrations of the senses to sober reflections on how little of the world we actually perceive.

At first glance, the quest for coherence in the Ars magna is daunting, despite what some have argued.27 There was something in Kircher’s text for everyone: for botanists, there were descriptions of the effect of light on plants, including, of course, the heliotrope or sunflower, whose movement Kircher had discussed in his Magnes as an example of sympathetic correspondences but which he explained here as a mechanical reaction to the heat of the sun; for zoologists and anatomists, there were discussions about the structure of the eye and of phosphorescent animals; and for astronomers and astrologers, there were extended ruminations on the motions of the heavens and their effects on the terrestrial realm.

The reader of the Ars magna is constantly shuffled between image and text, text and image; as a result, the work is “neither an illustrated text nor a book of images” and thus requires a “double reading” which some, at least, have found disconcerting.28 We might extend this observation to both the Magnes and the later Mundus subterraneus as well, for they too exemplify this constant movement between image and text. The idea that this “double reading” should be disconcerting recalls, too, claims that Kircher sought to “unsettle the grammar of visibility,” not merely in an epistemological sense as witnessed in the previous chapter but as embodied in the structure of his books as well.

The Ars magna was bewildering in other ways as well: it overflowed with axioms, theorems, definitions, and hypotheses, containing “84 definitions divided into 6 groups, 25 axioms in 3 groups, 10 pure hypotheses, 13 hypotheses ‘or pronouncements’ and 13 other hypotheses ‘or postulates.’” This was in addition to the Propositiones, Theorumena, Theorema, Petitiones, Consectaria, Canones, Problemata, Regulae, Pragmatia, Corollaria, Prolusiones, Experimenta, Machinamenta, Parastasis, Distinctiones, Technasma, Fabrica, Usus, Metamorphoses, and Epicherema with which Kircher sought to establish his claims. In effect, these numerous axioms became a sort of trompe l’oeil, a repeated rhetorical illusion: while appearing to create an elaborate philosophical edifice that confirmed Kircher’s claims, they were often accompanied by little more than the hoary propositions of ancient and medieval authorities.29

This rhetorical illusion, in which Kircher dressed up traditional sources of authority in the guise of a sophisticated but empty technical vocabulary, may have allowed him to conform, at least ostensibly, with the philosophical and pedagogical foundations of his order while simultaneously reaching towards the vocabulary and methodology of a new, emerging “science.” This is bolstered by the fact that Jesuit educators in this period still taught and commented upon the same authorities from whom Kircher borrowed his own claims, even as proponents of the “new philosophies” turned away from these authorities in ever-increasing numbers. Whether Kircher deliberately engineered this textual trompe l’oeil or it was instead merely a reflection of his idiosyncratic approach to knowledge, however, it illustrates a larger truth about the Ars magna: it was a text that occupied rhetorical and intellectual spaces somewhere in between different approaches to natural philosophy. Kircher did not shy away from the ideas and arguments advanced by the “new philosophies”; indeed, in the first pages of the Ars magna he described the observations of the sun made by both Galileo and Kircher’s Jesuit contemporary Christoph Scheiner, and included Kepler among the “many modern philosophers” who had claimed that the sun was a solid body. Kircher’s judicious and cogent discussion of these modern ideas, however, alternated with references to Aristotle and Albertus Magnus, creating an elaborate synthesis in which all authorities, modern or otherwise, appeared to support one another.

If Kircher relied occasionally on the testimony of traditional authorities, however, he certainly did not always do so in service to the Peripatetic philosophy. In fact, there are several points in the Ars magna where he articulated what appears to be a sly refutation of the Peripateticism upheld by his own order. Chevalley claims that Kircher’s attitude towards this philosophy took the form of “two distinct tactics: that of frontal attack, and that of irony.” The frontal attacks were numerous but carefully hidden, and Kircher used them to denounce “the abstraction of the scholastic philosophy, its fear of reality, its refuge in speculation.”30 It is more difficult, of course, to read for irony in a printed text, especially one published centuries ago. There are indications, however, that Kircher sought to present the principles of Peripateticism in a distinctly ironic tone; for example, in the midst of describing various examples of glowing animals and minerals, he suddenly presented a “scholastic disquisition on the nature and influence of light in the sublunary world, and its causalities” (De natura, & efficientia Luminis in mundo sublunari, eiusque causalitatibus, scholastica disquisitio).31 What followed was a ponderous exercise in Peripatetic logic, in which Kircher described illumination (lumen) with reference to each of the four Aristotelian causes: final, material, efficient, and formal. After devoting a lengthy paragraph to each, he concluded with the following:

Light therefore is known to be nothing other than a sensible quality produced by a shining body and present in a transparent [perspicuo] body, to which it assists in the engendering of heat, the detection of colors, and the sense representation of shining things, and by which it can be conserved for a long time in a transparent [diaphano] thing. And indeed this definition touches upon all the causes of light: formal, provided that it articulates a sensible quality; material, provided that it places itself in transparent bodies; efficient, provided that a real efficient power is to be preserved by a shining body; and final, provided that it articulates the production of heat, and the detection of colors.32

Just two pages previously, Kircher had considered Peripatetic arguments that sought to establish light as an accident:

That which is present or absent, without being subject to corruption, is an accident: light is present in the air and in a transparent thing without the corruption of the same; therefore illumination [lumen] is an image [imago] of light [lucis], and the visible species of a glowing thing [rei lucidae]; but an image representing an object in the cognitive faculties [of the mind] is not a substance, but an accident: therefore [light is an accident].33

There is a sense of the absurd about these passages, an impression that Kircher was casting sly aspersions on this kind of Peripatetic reasoning. It was the sort of exercise that the early modern philosophical reformers despised, arguing a great many things but ultimately saying nothing—after all, what possible use could there be in affirming that light was an accident rather than a substance in its own right? Kircher seems to encourage us to laugh along with him, to shake our heads at such reasoning, the absurdity of which was made all the more clear by the fact that these “scholastic disquisitions” were presented as a clear non sequitur, a jarring disconnect from the surrounding pages and their more engaging descriptions of glowing minerals and other wondrous phenomena (to which Kircher returned promptly).

An attentive reader might have understood that these explanations did not reflect how Kircher himself understood light. These were not formal disquisitions on the nature of light undertaken in the first pages of the text, as Kircher did in the Magnes; instead, he used these arguments to demonstrate how ineffective the medieval scholastic tradition was in describing or understanding light, with the added implication that modern, Peripatetic explanations suffered from the same problems. One might go further, too, and argue that this sort of dismissive attitude towards Peripateticism was present as well in the earlier Magnes, which hurried through a standard Aristotelian disquisition on magnetism in its opening pages before quietly but firmly abandoning such reasoning for the rest of the book. Kircher had an ambivalent relationship with the censors within the Society, whose approval was required before any work could be published; perhaps these nonchalant gestures towards a conventional Aristotelian philosophy were intended to satisfy the long-standing requirement that the Society adhere to Aristotle in matters of natural philosophy.34

If Kircher upheld the philosophy of Aristotle only in letter rather than in spirit, one might link this to a question he posed in the Ars magna. If, according to Aristotle, nothing is in the mind that was not first in the senses, “how then,” Kircher wondered, “shall we philosophize correctly and fully concerning the fabric of natural things, if we do not know the arrangement of their most hidden parts?”35 How, in other words, can we base the study of nature on the use of the senses when so much of nature is hidden? We have already seen how Kircher answered this question within the boundaries of his museum, and as part of his discussion of magnetism. In both cases, he suggested that the intervention of artifice could reveal the hidden operations of nature, exposing them to scrutiny by the workings of gears, turnstiles, and mirrors. Here, in the Ars magna, he articulated the same idea, for he raised these questions as part of his discussion of the microscope. “So great is the deceit of our senses,” Kircher claimed, that we will never arrive at a complete understanding of nature “unless [the senses] are propped up by something.”36 In this case, Kircher placed his hopes in “that divine science of optics.”37

It is surely no coincidence that on the frontispiece to the Ars magna, which portrays four different sources of illumination—sacred authority and reason are at the top, profane authority and the senses at the bottom—the telescope represents the senses. One might read this pictorial schema as upholding a predictable Aristotelian arrangement in which reason is pre-eminent to the senses, emulating closely a similar representation on the frontispiece to Christoph Scheiner’s Rosa Ursina (1626–1630). In Scheiner’s portrayal, the senses—aided once more by a telescope—provided only a clouded and fuzzy picture of sunspots, while the light of reason, illuminated directly by God, depicted these sunspots with perfect clarity. While it is true that Scheiner sought to preserve a Peripatetic epistemology as the foundation of his astronomical work, it is less clear that the frontispiece of Kircher’s Ars magna presents the argument that the telescope and, by extension, the senses are poorly suited to the investigation of nature; such a claim is difficult to establish from the illustration alone.38

Though we might view these Jesuit frontispieces as an explicit indictment of the senses in relation to reason, with the latter always pre-eminent, the relationship between the two was far more complicated for Kircher. This is made clear not only by his unstinting attention to the role of the senses in the acquisition of knowledge, in the Ars magna and elsewhere, but also by his clear realization that the exercise of reason is dependent on the senses, most particularly in the study of nature. Why else would he insist so strongly on “propping up” the senses with the aid of optics and other forms of artifice? His rhetoric throughout the Ars magna was no different from that articulated in his museum: if we are to see and understand the workings of nature, artifice must support our senses, whether by actually augmenting our senses, as with the microscope, or by providing a tangible manifestation of processes and forces that would remain otherwise insensible.

Figure 5.3 The frontispiece to the Ars magna lucis et umbrae, showing the four sources of illumination: sacred authority, reason, profane authority, and the senses.

Source: Courtesy Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Kircher’s concerns about the fallibility of the senses dovetailed with an explicit and perhaps surprising lack of certainty in his explanations of light. As part of his discussion of the microscope he stated firmly: “It is indeed absolutely plain that all things seen by many of us are in truth other than what they seem,” a reference to the unfamiliar and strange appearance of minerals, plants, and animal hairs under magnification.39 The microscope, of course, “propped up” his senses and allowed him to witness the true form of things, but Kircher’s avowal that things are “other than what they seem” was a stark reminder not only of sensual fallibility, but also of the difficulties inherent in knowing anything at all with certainty.40

In fact, Kircher seemed determined in the Ars magna to ignore the pursuit of certainty, a determination that he linked explicitly with his reservations about Peripatetic arguments about light and an ostensible lack of patience for the tepid speculation that characterized many such arguments. When he addressed the question of light rays, he noted that Aristotelian philosophers had debated for centuries whether rays were a material substance, or a space, or something else, but he stated bluntly that he himself would not be troubled by such idle speculations: “nevertheless in this perplexing business it ought to be said that I do not know” (quid in tam perplexo negotio dici debeat nescio). In other words, he felt free not merely to shrug aside the entire question of what rays were, but to admit happily that he himself had no idea what they were. He went on to add that he would be better off simply concluding nothing at all rather than appearing to contradict either “the new Philosophy” or the assertions made “in the preceding book,” by which he may have meant the Aristotelian explanations for light that he had bandied about in the first book of the Ars magna.41 These were remarkable statements: rather than choosing one explanation over another, Kircher simply opted out, choosing to conclude nothing at all.

The via media promoted by Kircher resembled, in its outlines, the epistemology at work in his museum. The Kircherian collection occupied a space somewhere between conventional Peripateticism and other ways of investigating nature—its attention to the Aristotelian virtue of collective assent, for example, was balanced by its unmistakable focus on the singular experience. The Ars magna, too, embodied many of these dichotomies, with its traditional authorities dressed up as Machinamenta or Experimenta and its ironic juxtaposition of Aristotelian logic with a defiant and explicit lack of certainty. At the same time, there were other ways in which the Ars magna overlapped with the Kircherian collection—most significantly, perhaps, in the attention paid to spectacle. Indeed, Kircher addressed the potential power of spectacle directly, taking some pains to highlight its utility at several points in the Ars magna. This dovetails neatly with the messages offered by the Kircherian museum, which Giorgio de Sepi described as “the epitome of philosophical practice” and which established in turn the importance of spectacle to that practice.

Kircher’s emphasis on spectacle as utilitarian rather than frivolous stood in sharp contrast to the claims made by contemporaries later in the seventeenth century, almost all of whom were northern Protestants who maligned his interest in spectacle and wonder as antithetical to sober, “proper” philosophical endeavors. Christopher Wren, for example, once remarked to Lord Brouncker shortly before Charles II was to visit the Royal Society that “to produce knacks only, and things to raise wonder, such as Kircher, Schottus, and even jugglers abound with, will scarce become the gravity of the occasion.”42 Wren deliberately cast Kircher and his disciple Gaspar Schott as “jugglers,” more interested in producing wonder in their audiences than in legitimate or proper natural philosophical demonstration. But Kircher had his defenders, too. Robert Moray—who, unlike Wren, had spent time in Catholic Europe—wrote to Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, that “[Kircher] meddles with too many things to do any exquisitely, yet … none goes beyond him, at least as to the grasping of variety: and even that is not onely often pleasurable but usefull.”43 Moray’s insistence that the Jesuit father’s spectacular displays could be simultaneously useful and pleasurable certainly gave more credit to Kircher than most contemporaries would otherwise have countenanced, particularly within the confines of the Royal Society. This English squeamishness about spectacle and public display was rooted, at least in part, in a widespread anti-Catholicism that emerged in the late sixteenth century in England and persisted into the seventeenth century. Catholic courts were notorious for their lavish theatrical displays—something Wren should have remembered when wondering how to impress Charles II, who spent much of his exile in both France and Spain—and the Catholic Church and its priests were reviled in England as relying on trickery and superstition in order to defraud their hapless congregations.44

For all their seeming distaste for elaborate displays, however, members of the Royal Society exploited spectacle freely when they deemed it necessary. One of the most prominent of the Society’s early members, John Wilkins (1614–1672), published an entire book devoted to a “mathematical magick” that resembled nothing so much as the same “magic” endorsed and disseminated by Kircher and his disciples. Wilkins even designed and constructed a “speaking statue” nearly identical to one in the Kircherian collection.45 Then, too, there were the phosphorus demonstrations engineered by members of the Royal Society in the latter decades of the seventeenth century, elaborate public-relations exercises that depended largely upon spectacle and wonder. Members of the Society invited other virtuosi as well as women and children to a variety of demonstrations in the 1670s and 1680s, many of them chemical in nature.46 Such demonstrations were an integral part of the Society’s attempts to inculcate a public culture of science, as well as to advertise their own collective acumen. Phosphorescent substances, of course, were well-suited to such spectacles: they were rarities and thus exotic, while also capable of exciting the senses of an attentive audience.

Members of the Royal Society professed themselves to be leery of depending too greatly upon spectacle, however, which could pose a “moral danger” if “observers [are] diverted into the simple gratification of the senses and hence … fail to progress to the stage of judgment and ratiocination.” Thomas Sprat, who chronicled and codified the ideals of the early Royal Society, claimed in his Historie (1666) that the Society “spurned the examination of monstrous, extravagant, and rare phenomena” for this same reason, though the Philosophical Transactions published by the Society would seem to give Sprat the lie.47 The Transactions contained numerous examples of the experimental “science” practiced by members of the Society, but they also communicated no shortage of monstrous births, strange celestial lights, and other typical examples of wonders and marvels—precisely those rare and extravagant things, in other words, that Sprat claimed to abhor.48

While Sprat himself perceived some value in the “sensible pleasure” excited by experiment, and praised the “most diverting Delights” produced by experimental demonstrations that had “power enough to free the minds of men from their vanities, and intemperance … by opposing pleasure against pleasure,” the public line taken by most in the Royal Society was that spectacle was acceptable only if it led to a judicious consideration of physical properties or other philosophical material.49 To cross into the realm of spectacle for its own sake was to engage in the “knacks” and other foolishness of which they deemed Kircher particularly guilty. Circling back to the Ars magna, however, we find Kircher himself suggesting that philosophers should exploit the spectacular nature of phosphorescent substances in order to excite the admiration and interest of an audience. Moreover, he made this suggestion some thirty years before the Royal Society began performing their public demonstrations with phosphorus. In a section entitled, De Photismo Lapidum; De Lapide Phenggite, seu Phosphoro minerali, Kircher explained that rarities like phosphorescent substances could “vehemently excite” the study of causes and effects, and that the examination of “things new and rare” produced a wide range of opinions.50 What he described was not spectacle for its own sake; it is clear that he endorsed the use of wonder and spectacle in “exciting” study and philosophical contemplation, precisely the line taken decades later by Wren, Sprat, and their contemporaries in England.

Kircher’s disquisition on the utility of spectacle fits perfectly into both the Ars magna and his wider epistemology. One can read the Ars magna as an extensive commentary on both seeing and knowing, and spectacle in itself certainly overlaps with both of those concerns. The magnetic machines and catoptrical devices scattered throughout both Kircher’s collection and the pages of his books were designed and displayed precisely because, as spectacles, they could excite interest and encourage contemplation. The irony here is that Kircher used a book about light and vision to undermine the sensual foundations of natural philosophy, and ultimately to question whether observation in itself could ever establish certainty. At the same time, however, he provided his readers with ways to circumvent the frailties and failings of their senses: pieces of artifice that might support the exercise of the eyes, the twinned practices of spectacle and bemusement as incitement to philosophical investigation, and novel, probabilistic approaches to the most basic of philosophical problems.

The study of geology became a preoccupation for a range of early modern thinkers in the latter decades of the seventeenth century, and only increased in popularity into the eighteenth century.52 Amidst this growing interest, Kircher’s Mundus subterraneus remains an influential example of seventeenth-century theories about the subterranean realm. We know that it was awaited with some eagerness in England, where Henry Oldenburg, then secretary of the Royal Society of London, relayed news of its impending publication in a letter to Robert Boyle in August of 1664; Kircher’s publisher in Amsterdam had assured Oldenburg that it would be printed “within six weeks.”53 Once it appeared in London the following year, Oldenburg wrote again to complain of the expected cost—“50 shillings at least, and yet but one volume,” he lamented—and after seeing it for the first time, commented in yet another letter to Boyle, “I doe much feare, he gives us rather Collections, as his custom is, of what is already extant and knowne, than any considerable new Discoveryes.”54

Oldenburg ultimately deferred to Boyle in judging the merits of Kircher’s work, though he wrote to Benedict Spinoza in October of 1665 that “although [Kircher’s] arguments and theories are no credit to his wit, yet the observations and experiments there presented to us speak well for the author’s diligence and for his wish to stand high in the opinion of philosophers.”55 In fact, members of the Royal Society were willing to attempt some of the experiments described in the Mundus. Oldenburg wrote to Robert Moray in November of 1665 that Kircher’s theories on the tides were especially interesting: “… he produces severall Experiments to evince, that the Moon is the sole cause of those Sea-reciprocations, by a Nitrous quality and Dilating faculty, he hath found in her: of which Experiments it will perhaps be worth while to make trialls … “56 Boyle himself wrote that he intended to test Kircher’s ideas “concerning the Ebbing & flowing of the sea,” but a few days later he reported that “the Expt about Salt & Nitrous water exposd to the Beames of the moone did not succeed as Kircher promises, but as I foretold.”57 Oldenburg’s reply said only, “’Tis an ill Omen, me thinks, that the very first Experiment singled out by us out of Kircher, fails, and it ’tis likely, the next will do so too.”58

The inability to replicate Kircher’s claims may have done some damage to his reputation in England, though it was true that experiment was an uncertain business in the seventeenth century; the trials made by members of the Royal Society were not necessarily nor easily replicated themselves.59 A review of the Mundus appeared in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions in the same year as Boyle’s failed experiments and spoke of it as a search into “the recesses of Nature” as well as emphasizing Kircher’s study of “the Great Secrets of Nature,” but otherwise passed no particular judgment on the work.60 Modern commentators have been less kind; one scholar claimed recently of the Mundus that “[Kircher] simply fills pages and pages with descriptions of a bewildering variety of novelties without any coherent synthetic explanation.”61

A close examination of the Mundus, however, reveals that Kircher used this particular work to encourage a meaningful and intellectual contemplation of the hidden depths of the Earth through a mix of iconography and probabilism, presenting to his audiences a speculative glimpse of the world as it might be. Here, then, is the coherence that has eluded some historians: not a coherence of explanation, but one of method and epistemology. More than merely a “bewildering variety of novelties,” the Mundus subterraneus actually worked in many respects like Kircher’s earlier Magnes. Similarly to his work on the magnet, the Mundus also emphasized the underlying unity between things, most prominently between the natural and the artificial. Using the Earth as his focal point, Kircher spun an elaborate and complex web of correspondences and links between a wide array of disparate subjects and phenomena, everything from complex machines designed to pull fresh air into mines and fill rooms with pleasing scents to descriptions of dragons, demons, and giants.

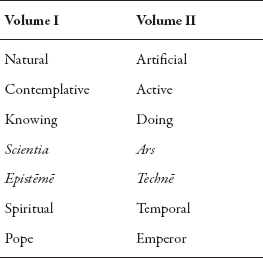

The structure of the Mundus remains largely unexplored by historians, perhaps because so few see it as anything more than a collection of unconnected miscellanies. Kircher, however, created a series of narrative dichotomies that simultaneously juxtaposed and opposed the ideals of Art and Nature, knowing and doing, contemplation and action, and these dichotomies guide the attentive reader to a contemplative and speculative consideration of both the hidden interior of the world and its utilization and exploitation by humanity. Alongside the iconography and imagery that appears throughout, the structure of the Mundus works to transform this text into, again, something very like a meditative compendium of those hidden depths. Its purpose was to encourage the imaginative contemplation of the unseen rather than to inculcate a culture of direct observation and experimental precision, something that puts Kircher at odds with the intellectual culture developed by institutions like the Royal Society and that explains, at least in part, why Kircher’s work has been so frequently misunderstood.

Structurally, Kircher divided the Mundus in two. Volume I focused on “the admirable structure of the terrestrial globe,”62 and consequently described that structure in great detail, exploring mountains and volcanoes, the oceans of the world (including the first detailed maps of ocean currents), the structure of underground springs, and meteorological phenomena caused by terrestrial exhalations. In short, this first volume focused on Nature itself, and on the contemplative, philosophical knowledge of natural processes and phenomena. Volume II, by contrast, focused on the “fruits of the Earth” and their exploitation by humanity. Kircher discussed the work of Nature-as-artisan in the production of gemstones and fossils as well as the human artisan’s production of colored stones and artificial gems, before enumerating at length the varied properties of minerals and metals and their uses in the production of medicines, dyes, and other practical products. Kircher also treated alchemy at length, alongside images of chemical furnaces that he himself designed and used in the Collegio Romano. This volume, then, exulted the active pursuit and utilization of Art. Further dichotomies drawn throughout the text underscored the importance not only of establishing a balance between the disparate realms of Nature and Art, moving from one to the other in the pursuit of both natural knowledge and artisanal control, but also of the accumulation of the probable through individual contemplation and the artificial imitation of nature’s hidden realms and forces.

For Aristotelians, the imitation of nature was generally unproblematic; it was a medieval commonplace that “art is the ape of nature.” Aristotle, in his Physics, had taught that “the arts either, on the basis of Nature, carry things further [epitelei] than Nature can, or they imitate [mimeitai] Nature.”63 There is evidence, however, that, over the course of the seventeenth century Aristotelian thinkers increasingly turned their attention to the idea that art could do more than merely imitate nature.64 In fact, the possibility that art could “carry things further” than nature—that is, that it could perfect natural processes—played a vital role in early modern ideas about experimentalism and permitted some prominent Aristotelians to embrace experiment as a legitimate means of acquiring knowledge about natural processes.65 Kircher himself was ambivalent about this aspect of art, at least as concerned things such as the alchemical transmutation of metals, which he deemed impossible and potentially impious (an opinion he shared with the Jesuit commentators at Coimbra).66 What interested him more was the artificial imitation of natural phenomena, and in the Mundus he sought to convince his readers that two separate forms of imitation—the experimental emulation of subterranean processes, and the pictorial representation of what lies hidden beneath our feet—could aid, or even replace, the philosophical contemplation of the hidden depths of the world.

Dichotomies and oppositions permeate the Mundus, a fact that was made clear in the respective dedications of the two volumes. Kircher dedicated the first volume to Pope Alexander VII, and therein he spoke of “a road into the inferior parts of the Earth,” assuring the pontiff that, like the Cynic philosopher Diogenes, he would orient himself with reference to Alexander’s pious light so that he might describe clearly the shadows that block our sight of the Earth’s interior and avoid their “trampling underfoot [his] wandering and labors.”67 There were, in fact, numerous references to shadows throughout the Mundus, just as there had been in both the Magnes and the Ars magna. Kircher repeatedly promised to take his reader through these shadows and into the most hidden and innermost depths of the Earth so as to see clearly what lay beneath, relying on contemplation and reasoning in his attempts to do so. This was a pious and philosophical endeavor, the study of God’s work and its “admirable structure,” thereby framing the investigation of nature as both intellectual and spiritual.

The first volume also ended on a spiritual note. In the brief conclusio, Kircher framed his investigation of the interior of the Earth in a religious language, speaking of the “hidden temple of the Geocosmos” (occulta Geocosmi sacraria) and noting that, having struggled “to burst forth from the horrid and inaccessible abysses of the subterranean world,” all that remained was to offer thanks to God, whose innumerable marvels resided even in the “hidden abysses” of the world.68 The impressions Kircher presented in this first volume, of the pious and faithful Jesuit traversing the deep shadows of the underworld in his quest for truth and enlightenment, permit us to understand his Mundus as a spiritual as well as a philosophical journey through the subterranean world. The themes were those of contemplation and scientia, emphasized most particularly by an emblematic and figurative iconography of the Earth’s interior that worked, as we shall see, to guide the reader on precisely the contemplative journey that Kircher himself articulated.

The second volume of the Mundus, by contrast, was cast as a celebration of humanity’s mastery over God’s handiwork, a change in tone that manifested itself, again, in a dedication to a powerful patron. While he had dedicated the first volume to the pope, however, Kircher chose to dedicate the second to Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor from 1658 to 1705. Kircher opened his dedication to the Emperor by celebrating the tributes Leopold had received “from every part of the terrestrial sphere” and praising his victories, all of which would lead to the Emperor’s eventual rule over the entire world. Kircher then cleverly adapted these allusions to worldly domination to the subject of his own work, offering Leopold the Mundus as a tribute that would grant him mastery of the interior of the Earth so that his dominion over the terrestrial sphere would be total.69

Kircher also promised Leopold that the Mundus would act as both book and mirror, and that by looking within, the Emperor would see into the most profound depths of the Earth “by means of a sharp penetration of the eyes.”70 This rhetoric, in which the Mundus became simultaneously a reflection of the Earth’s hidden depths and the device that permitted the Emperor to penetrate with his eyes to the very core of the world, is significant. What Kircher promised Leopold was not a pious journey through obscuring shadows that would be guided and directed by the light of faith, as he did with Alexander, but rather, the ability to uncover the hidden depths of the world for himself, with allusions to mastery and dominion over those depths. This theme stretched throughout the second volume, with its emphasis on “the fruits of the Earth” and humanity’s manipulation, utilization, and mastery of them.

By choosing the pope and the emperor as patrons of the Mundus, Kircher shaped a significant dichotomy between spiritual and temporal power, praising both as worthy of respect and admiration but also claiming that each was suited to a particular approach. One could certainly extend the analogy to the opposing realms of Art and Nature, or even contemplation and experiment. When addressing Alexander, Kircher emphasized the importance of contemplation and knowledge, framing his endeavor as a solitary journey through shadow that the dual virtues of faith and reason both illuminated and guided. When speaking to Leopold, however, Kircher emphasized the importance of action and mastery: he not only praised the emperor’s worldly and temporal actions and celebrated their triumphant and victorious outcomes, but also urged Leopold to use this text to seek out the depths of the Earth and thereby come to control them.

The dichotomy that Kircher created with the Mundus revolved around a number of simultaneous divisions: spiritual/temporal, contemplative/active, knowing/doing. These divisions were themselves subsumed within the central dichotomy that explicitly structured the whole of the Mundus, the division between Art and Nature, between the handiwork of God in Volume I and the handiwork of humanity in Volume II. Kircher thus shaped the structure of the Mundus in this fashion:

This rhetorical strategy illustrated Kircher’s equal commitment to two sets of ideals. More importantly, however, he demonstrated to his audience that, whether we rely upon philosophical contemplation or artificial experiment, our understanding of the subterranean world would remain probable, not “factual.” As Kircher would later argue, how could we know that realm with certainty when no one has ever seen it for themselves? It was the same idea he had articulated in the Ars magna, when he wondered how we could know anything with certainty if causes and phenomena remained hidden. In the investigation of the subterranean world, certainty was neither possible nor, arguably, desirable.

The inability to sense or experience directly certain parts of the world was a central preoccupation not only of Kircher’s, but of Cabeo’s as well, and of other Jesuits that included both Gaspar Schott and Francesco Lana de Terzi. Throughout the Mundus the careful reader encounters the implicit argument that, in the absence of direct experientia, one could employ the contemplative mind as a means of perceiving those things that would otherwise remain “un-experienced” and unknown. The mind depended in turn upon artificial imitations of nature, both experimental and pictorial, much as the meditative practice of the applicatio sensuum depended upon visual cues.

Kircher more specifically spelled out his efforts to reveal and expose the hidden through the intervention of experiment and artifice early in the Mundus; we might recall that he promised his readers that they would find no occult causes in his text: “There is no occurrence in this work of hidden causes, because experiments made by me have not allowed it.”71 Niccolò Cabeo had resorted to a similar rhetoric almost forty years previously, when he promised that readers of his Philosophia magnetica would not have an occult quality “thrust upon” them. Recall, too, that Kircher had claimed in both his Magnes and the Mundus that occult qualities were “the asylum of ignorance.” Like Cabeo, he resolved to explore natural phenomena without reference to “hidden causes” or the occult qualities of conventional Aristotelianism. Kircher also attached particular importance to his own experiments: not only did he take credit for this act of revelation, but he also alerted his audience to the central role of experiment and artifice in what he was attempting to do. The Mundus, then, was not intended to work as a purely theoretical revelation of nature’s secrets. As the dedication to Leopold made clear, it was in active utilization and practical experimentation that revelation would become possible.

Given the central role of such experiments, we return to the question of why Kircher included experiments that ultimately failed, particularly after he had boasted of their revelatory power. Perhaps Kircher simply failed to try these experiments himself before including them in the Mundus, or perhaps their inclusion—tested or otherwise, workable or otherwise—possessed some merit in itself. Assuming for the moment that Kircher was neither negligent nor incompetent (both possible, but difficult to prove and unhelpful in any case) we must focus our attention on the latter possibility: that the experiments and claims described by Kircher possessed, for him, some value beyond their reproducibility by others. The experiment attempted by Robert Boyle concerning the tides failed, but presumably he did much the same thing as Robert Moray, who reported to Oldenburg that he had dutifully filled a basin with water, added both salt and nitrate, and set it under the light of the moon to watch for perturbations that might signal that the water was experiencing a tidal force.72 So small a trial could hardly capture Kircher’s larger achievement in the Mundus; he was one of the first to attempt to map tidal currents on a global scale, using reports he received from mariners and fellow Jesuits traveling around the world.73 Perhaps, then, the value of Kircher’s proposed experiments lay not in their ability to capture or codify facts about the world but rather in their ability to spur the mind to a contemplation of what might be possible. Contrary to our expectations, Kircher may have intended his experiments and machines to complement this imaginative contemplation of the probable, not to usurp it with the creation of “matters of fact.”

Kircher’s probabilistic experiments could also function as directed revelations of hidden natural things, made possible by the imitative power of artifice. Indeed, the notions of imitation and revelation are closely linked, for when one proposes to imitate through art an aspect of the natural world that is hidden, insensible, or otherwise difficult to know, one effectively renders such things visible and knowable, at least as far as artifice will allow. This makes sense when we consider that many of the machines and instruments that Kircher displayed in both his museum and the pages of his texts exhibited in their activity particular natural powers and processes that one could not otherwise observe directly. For example, consider the way in which Kircher describes the art of chemical distillation: as an imitation of nature’s subterranean processes.74 The artisan or chemist who engaged in the act of distilling imitated or duplicated a natural process that normally took place in the subterranean depths, a common trope from alchemical theory and practice that envisioned the purification of metals by the alchemist as an emulation of the same processes that naturally ripened metals within the Earth.75 The Mundus thus presented its readers with the promise that they would not only see the interior of the world in the act of distillation itself but would also be able to duplicate and control its processes through the intervention of ingenuity and artifice.

Artifice may have had a central role in Kircher’s project, but the elaborate dichotomy that he created between the artificial and the natural guided the receptive reader, paradoxically, towards a powerful notion of universality, of a single project that sought to bind together a series of disparate, even opposite, ideals in pursuit of a universal kind of knowledge. The Kircherian collection similarly embodied this notion of universality by linking together a host of disparate objects into a single, elaborate theatrum mundi. Pervaded by dichotomies as it is, the Mundus is no different: it revealed the true nature of the subterranean world only through the juxtaposition of those opposing categories, by both spiritual contemplation and active experimentation. This text is nothing else but a theatrum mundi subterranei.

As both an Aristotelian and a Jesuit, Kircher was well suited to finding a balance between seemingly disparate ideas. As an Aristotelian, he could advocate the use of experiment and artifice in the pursuit of natural knowledge, using Aristotle’s own notions of the imitative and perfective arts as the keystone of a scheme in which the natural and the artificial worked together, each reinforcing the other. As a Jesuit, Kircher himself embodied the balance between the contemplative and the active, for this was an integral part of the Jesuit mentality. Consider, for example, the movement from Jéronimo Nadal’s meditative images and the solitary contemplation of Christ’s life to the active emulation of Christ himself in the apostolic ideals of preaching and charity.76 Consequently, there were numerous resonances between Kircher’s strategies in the Mundus and the wider intellectual and spiritual contexts that surrounded both Kircher himself and the larger Society.