Some years after serving as disciple and assistant to Athanasius Kircher, Gaspar Schott still carried the indelible stamp of his mentor. He was fond of mentioning Kircher in his own works and of describing, enthusiastically, some of Kircher’s more implausible ideas. Unlike his mentor, however, Schott remains largely unknown today. During his lifetime, much of his notoriety came from his association with Kircher: he edited the latter’s controversial Iterum extaticum, which raised eyebrows among the Society’s censors for what some saw as a tacit endorsement of heliocentrism, and he also spent some time working in the Kircherian museum before his superiors sent him back to Germany. From those northern hinterlands, Schott produced a number of texts that clearly bear the hallmarks of Kircher’s own intellectual project. In one of these texts, the Physica curiosa, we have already seen that Schott pronounced an end to the occult power of the remora; in the Magia universalis naturae et artis (1657–1659) and the Technica curiosa (1664), he more explicitly considered how to expose the myriad marvels of nature.

Schott’s published works contained themes and practices already present in Kircher’s own publications, but he did not merely reiterate the ideas of his mentor. Instead, he carried Kircher’s ideas further, expanding upon two preeminent themes in the Kircherian corpus: the joining of art and nature, and the judicious use of spectacle. Schott’s vision of a “universal magic” was both more ambitious and more transgressive than anything proposed by his mentor; while Kircher played with the opposition between nature and artifice, using each to explain and reveal the other, Schott blurred the boundaries between these two realms to such an extent that those boundaries sometimes disappeared entirely. At the same time, Schott played an elaborate and sometimes bewildering game with his audience, presenting phenomena as marvels with one hand while, with the other, exposing these mysteries as commonplace demonstrations of basic natural principles. It was a strategy of presentation not dissimilar to the subtle games at work in Kircher’s museum, but was at the same time more extreme in its shuttling between obfuscation and revelation. My argument here is that this movement between hiding and revealing was Schott’s response to the prevailing culture of marvels that had occupied European intellectual inquiry for centuries. The fascination with the rare and unexplained overlapped, unsurprisingly, with phenomena that we have already explored, such as the category of the preternatural. With these things already challenged and scrutinized by natural philosophers across Europe, it was an opportune time for Schott to wrestle with the study of marvels; indeed, with Kircher as his mentor, it would have been surprising had he not turned his attention to hidden causes and mysterious effects, as in fact he did in all of his published works.

Marvels and wonders played an important role in shaping how early modern philosophers discussed and understood “scientific” experience.1 Francis Bacon, for example, incorporated marvels into his evolving system of natural philosophy alongside a host of other “particulars,” creating the sort of “preternatural history” in which wondrous (but natural) things became, as part of the Baconian program, merely another way to catalogue and understand the natural world. The Baconian impulse to gather and study such marvelous particulars left its mark on the nascent philosophical institutions like the Royal Society and the Académie Royale des Sciences, both of which collected and published reports of marvels well into the eighteenth century. That the study of marvels slowly disappeared from natural philosophy is indisputable, though why it happened remains a point of contention among historians, as we saw in Chapter 1. Ultimately, the decline of marvels probably had more to do with their being stripped of their cultural currency, and thus of relevance, than any proto-scientific movement to “disenchant” nature.2

At a glance, Schott presents something of a paradox. Though he immersed himself unabashedly within the culture of marvels, I will demonstrate that his primary interest lay in the demise of mystery, not its perpetuation. In this, he joined the ranks of contemporary “preternatural philosophers” who “understood their mission in Aristotelian terms: to explain away wonder. Theirs were to be the Herculean labors of a natural philosophy that quenched wonder with knowledge.”3 These preternatural philosophers thought of themselves as the “sworn enemies of wonder” who embraced the dictum that “knowledge of causes destroys wonder,” but it would be misleading to pretend that Schott was an enemy of wonder.4 Like his mentor, Schott was determined to exploit wonder in order to educate his audiences; he wanted his readers to marvel at insensible forces and causes before being taught how to understand them. At the end of his eclectic, encyclopedic works the only real object of wonder that remained was not the myriad marvels of nature but the ineffable power of the God that had fashioned them.

This ultimate goal may have been why Schott spent relatively little time worrying about the ontological distinction between the natural and preternatural that so occupied other contemporaries. This was replaced in his philosophy by the distinction between nature and artifice, illuminated over and over again by myriad acts of revelation. In this respect Schott resembled the “professors of secrets” who, decades earlier, had worked to expose the secrets of art and nature to audiences across Europe. These “professors” published their secrets as part of an effort to produce a more public kind of science and expose “the tyranny of cunning” in a way that brought “the reign of secrets to an end.”5 But while Schott may have embraced a more public science, he was at the same time wholly committed to, if not “the tyranny of cunning,” then at least a more playful and quixotic revelation of secrets than anything contemplated by these earlier “professors.”

We have seen that Kircher celebrated the use of experiment and, in at least some respects, participated in the changes sweeping through the intellectual culture of his day even as he continued to rely on traditional sources of authority. Schott, however, differed from his mentor in that he more self-consciously borrowed from different philosophies of nature, and appears to have been more interested in the activities and ideas emerging from the experimental philosophies after the middle of the seventeenth century; he corresponded with Otto von Guericke (1602–1686) on the subject of his pneumatic experiments, for example, and devoted considerable space in his works to the demonstration and explication of novel technologies and methods. While this was in keeping with the practices of other German Jesuits, who were generally willing to embrace the experimental philosophy of the late seventeenth century, this is not to say that Schott necessarily agreed with the philosophical interpretations advanced by contemporaries such as Von Guericke or Robert Boyle.6 In the case of these pneumatic experiments, for example, he stopped short of endorsing the existence of a true vacuum. Ultimately, Schott appears to have divided his philosophy between the measured and experimental revelations of nature embraced by contemporary Baconians and the baroque constructions of his idiosyncratic mentor. Indeed, this may be a good way of understanding Schott’s similarly idiosyncratic philosophy: the evolving sensibilities of the “new philosophies” filtered through the lens of spectacle, baroque artistry, and playful obfuscation.

Because Schott’s works have received so little attention from historians, my analysis here will be thorough in order to show that his idiosyncratic preoccupation with the secrets of nature permeated these texts, and that no matter how eclectic and wide-ranging their contents Schott’s chief desire was to reveal those secrets. At the same time, I will demonstrate that he disguised his revelatory intentions behind a façade of pseudo-marvels, time and again erecting elaborate veneers of mystery that he then systematically and carefully demolished. An attentive reading of Schott’s works cannot fail to notice that his so-called marvels ultimately went the way of the remora—namely, nowhere. In reading these works, we are witnessing the demise of the marvelous.

In some ways, Schott was as idiosyncratic a figure as Kircher himself, and possessed of a playful character that led to clashes with his superiors in the Society. When Schott published a short work entitled Joco-seriorum in 1662, he did so without first seeking approval from the Society’s censors, a blatant breach of the order’s rules. The Society’s General, Oliva, reprimanded Schott and ruled that the work did not meet the standards expected of the Society’s authors.7 This is unsurprising, perhaps, as the Joco-seriorum was mainly concerned with magical tricks and frivolous anecdotes such as “how to stab the head of a chicken so that it might remain alive”—a description of how one might attach the head of a chicken to a table with a knife without killing the unfortunate animal.8 Despite Oliva’s unhappiness with the work its publisher reprinted it in 1666, the year of Schott’s death, as Joco-seriorum naturae et artis, though it appeared under a pseudonym. It would go through several later editions as well as at least one German translation.

Though the Joco-seriorum was a work of pure frivolity, there are other, more pertinent elements of Schott’s thought that evince an equally unorthodox approach to the pursuit of natural knowledge. As part of his multi-volume Magia universalis naturae et artis he included a dedicatory poem composed by another Jesuit, Nicolaus Mohr, dedicated to St. Francis Xavier, the archetype of the Jesuit missionary. Mohr claimed of Xavier that “there was nothing unknown that he did not seek out, nothing inaccessible that he did not penetrate. … He illuminated secrets.”9 Schott himself referred to Xavier as “the great apostle of the Indies, the wonder-worker” (magno Indiarum apostolo, thaumaturgo) and also as Sancto Thaumaturgo, the saintly wonder-worker.10 This characterization of Xavier as a thaumaturge or wonder-worker fits neatly into Schott’s wider project, focused as it was on the use of spectacle and on Schott’s own wonder-working. Thus, we come to grips here not only with Schott’s identity as a Jesuit, confirmed by this focus on one of the Society’s most famous figures, but also with the wider project that played out in this and his other works. Linking the practice of wonder-working with the penetration of the inaccessible and the illumination of secrets through the figure of Xavier, Schott also defined his universal magic as the joining of art and nature, thereby arguing that it was only in the mingling of the two that we might come to see, understand, and manipulate the secrets of the natural world. The full title of the Magia promised to demonstrate “the hidden science of natural and artificial things by which, through the varied application of actives with passives, the spectacular effect of wonders and the miraculous invention of secret things are brought forth for the varied uses of human life.” This emphasis on “the uses of human life” reflected a pragmatic tone, and suggests that there was a utilitarian motivation to Schott’s works that some historians have ignored.11

In terms of ambition, Schott’s Magia universalis naturae et artis easily rivals the grandiose and lavish works produced by Kircher. The “magic” envisioned by Schott, focused as it was on the illumination of nature’s mysteries and the joining of art with nature, also shared numerous similarities with Kircher’s own intellectual projects. Though he rehearsed the standard definitions for both natural and demonic magic (and, as we have seen, discussed the existence of demons as part of his later Physica curiosa), Schott himself was untroubled by concerns about demonism or diabolism; his universal magic was resolutely natural in its causes, as indeed was that of Kircher. Schott, however, was far from ignorant of the controversies that sometimes attached themselves to contemporary theories of magic. Indeed, the first pages of the Magia universalis were an attempt to rehabilitate the very word “magic,” which, he informed his readers, was hated by many: “on being heard, ears and souls should be horrified, and if they should discern this same thing [i.e., magic] in a book so inscribed, it should be rejected immediately, and they should sentence it to be consigned to the flames.”12 He then mused on the possibility of substituting “a less odious vocabulary” to discuss the same thing, adding, “I should confess to having finally detached the Epigraph of Magic and restoring in its place Thaumaturgum Physico-Mathematicum.”13 His solution was an economical one: simply replace a word that carried too many negative connotations with a phrase that did not. Moreover, it was a phrase that connected wonder-working with the term “physico-mathematics,” which had been used by Descartes to denote the study of physical causes “formulated in mathematical terms,” and which remained popular in natural philosophical treatises of the latter seventeenth century.14 Thus, it would seem that Schott’s universal magic was an attempt to reconcile preceding and contemporary traditions of natural magic with the shifting outlines of the “new science” emerging in the seventeenth century.15

Contemporary Jesuits, as we know, took a keen interest in questions of ontology, especially where those questions involved insensible causes. Schott was no exception, though the ontological component of the Magia lay primarily in his attempts to determine the boundaries of the natural world. He promised his readers that, by making manifest those boundaries that might have been unclear, artifice could lessen or remove altogether the obfuscating power of the invisible or hidden parts of nature, as well as their ability to obscure the ontological boundaries of the natural. Schott’s thinking here had deep roots in Peripateticism and its sometimes fraught relationship between art and nature. His Magia suggested that, as artifice imitated and perfected the natural, it simultaneously demonstrated what the natural was, for art can never transgress the boundaries of nature. Thus, in its very operation, art comes up against those boundaries and exposes them to our collective view. This, then, was an exercise in ontological clarity, not dissimilar to those published by other Jesuits earlier in the century.

Some of Schott’s first words in the Magia clarified for his readers the preeminence that he ascribed to the study of this “universal magic” and its position in relation to the arts and sciences: “The magic of art and nature [is] the apex of all the sciences, the flowering of art, the discovery of secret things, the making of wonders, to which all arts, all sciences, are made servants.”16 What becomes clear throughout the succeeding dozen pages is Schott’s belief that it was the subjugation of a unified art-and-nature to his notion of a universal magic that lent the latter such utility and force, a claim echoed in the hymenaeus or marriage song dedicated to “the marriage of art and nature” (conjugio artis et naturae), a contribution composed by one Georgius Philippus Harsdorfferus, a “republican councilor” of Nuremberg.

Next was the Prologus Encomiasticus ad Lectorem, a lengthy poem composed by the same Nicolaus Mohr who had composed the dedicatory poem to St. Francis Xavier. Mohr’s “prologue” at the beginning of the Magia also emphasized the joining of art and nature, and characterized Schott himself not only as “the greatest disciple of Athanasius Kircher” but also as Obstetricans or midwife to the progeny of a conjoined art and nature, presumably Schott’s vision of a universal magic.17 Mohr further characterized this progeny as “that art which does not surpass the limits of nature” (Ars Naturae limites non egreditur),18 a significant though unsurprising remark echoed by Mohr’s later assertion that “[Nature] teaches itself to be limited through Art, not to be transformed; to be directed, not to be corrected; to be lifted up, not to be cast down” (limitari se per Artem docet, non immutari; Dirigi, non corrigi, elevari, non depravari).19 The rhetoric here was of nature knowing itself, of finding its proper arrangement and direction, through the intervention of artifice.

Mohr’s assurances that artifice will not surpass or transgress the limits of nature, but will instead elevate and guide, reflected the Peripatetic belief in art’s inability to supersede the powers of nature. Such claims, however, also clarify the way in which both Mohr and Schott proposed to use artifice in its joining with nature: as a means to both guide and elevate the latter, but also as the means whereby nature discovers its own limits. Significantly, this notion of art instructing nature also appeared in Kircher’s Mundus subterraneus—another text devoted to the joining of art and nature—where he claimed that, “if an effect of nature should be produced by art, at the same time, in this display, nature is taught by art to reveal [itself]” (si per artem naturalis effectus producatur, eadem arte naturam in eo producendo procedere docetur).20 Here, then, was a clear articulation of Schott’s desire to reveal the boundaries of nature. Like Kircher, he was convinced that one could use artifice to instruct nature, to encourage it to reveal itself to the gaze of the artificer. It was a desire that Schott also expressed in later works such as the Technica curiosa but that here, in the Magia, focused not only on varied examples of artifice but also on those parts of nature that must be revealed and explained before they can be understood.

Schott’s basic notion of “magic” followed almost exactly the definitions provided by Martín del Rio in his Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex of 1599, which Schott acknowledged as one of his sources.21 Schott and Del Rio both defined natural magic as the application of actives to passives, or agents to patients, which varied only in the time, place, and manner of application, and which only appeared to be a trick or miracle to those ignorant of the causes.22 Schott then defined artificial magic simply as the production of wonders (mira) through human industry and with the aid of various instruments.23 These were standard definitions for the time, but they are peculiarly unhelpful within the wider context of the Magia, which sought repeatedly to erase the separation between natural and artificial. Perhaps Schott saw this as a sop to the more conventional sensibilities of the censors, much as Kircher had included Peripatetic musings on the magnet before embarking on the decidedly non-Peripatetic project of his Magnes.

The juxtaposition of art and nature at the core of the Magia took a dizzying variety of forms, and was couched in a grandiose and flowery language that made the sober experimental accounts of Boyle and Hooke seem drab by comparison. Ultimately, however, Schott’s “universal magic” was a program for an operational philosophy in which the products of art were brought to bear on the study of nature. This was certainly not the rather more restrained experimental philosophy of the Royal Society, but it was comparable in its essentials. For example, as part of the first volume of the Magia Schott proposed to discuss Parastaticus, “the prodigious representations of things made by Nature and Art”; this included the wondrous representations made by Nature “in the air, in mountains, in rocks, stones, plants, and other things”—in other words, marvelous images found in mundane objects. He then added, “And lest Nature should seem to have conquered Art, we show how to represent these same things through Art, and by means of a prodigious magic, or at least an elegant and delightful magic.”24 Thus, whatever Nature can do, Art can do as well.

The implication hidden in Schott’s rather prosaic discussion was that, as the human artisan learns how to duplicate the prodigious feats of Nature, he comes to understand the hidden causes of those feats at the same time. One finds this theme repeated throughout the other books of the first volume of the Magia, which focused on the magic of optics, including the use of mirrors to produce bemusing spectacles (recall Kircher’s theatrum catoptricum) and the focusing of light through lenses to produce heat and fire. Intriguingly, Schott ended this first volume with a final book devoted to “Telescopic magic; or, On the making, use, and prodigious effect of the telescope and microscope.”25 After rehearsing the early history of the telescope, which contemporaries recorded as appearing first in 1609, Schott noted that Niccolò Cabeo had reported hearing of a rudimentary telescope even earlier than this: a device with two lenses, one concave and one convex, “used in one’s recitation of the Canonical Hours, with the concave [lens] being applied close to the eye [and] the convex close to the book.”26 Schott also believed that Giambattista della Porta had predicted the construction and use of the telescope earlier still, in his Magia naturalis of 1589, and noted as well that “optical tubes would seem to have been used” in antiquity.27

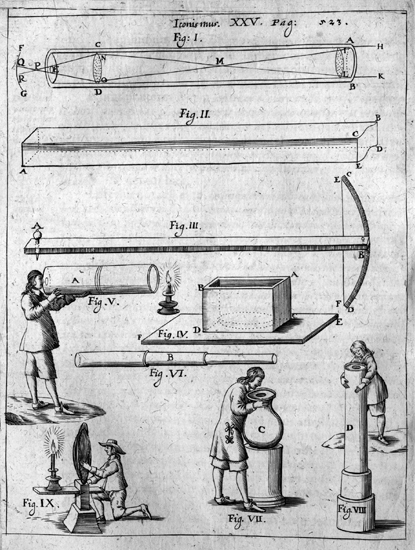

Figure 6.1 Various depictions of telescopes and similar devices, from Volume I of the Magia universalis.

Source: Courtesy Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology.

It is perhaps unsurprising that figures like Galileo and Kepler received little mention in Schott’s historical account of the telescope; instead, Schott seems to have veered carefully away from any discussion of the cosmological controversies sparked by the use of the telescope earlier in the century. It is noteworthy, however, that the frontispiece of the Magia features prominently the two cosmological systems accepted by the Society of Jesus, the Ptolemaic and the Tychonic; one of the female figures clutches in her hand a telescope, while the other points to putti arranging the heavens above. There we see the fruits of early modern telescopic observation: the crescents of Mercury and Venus, the cratered surface of the moon, Jupiter surrounded by its own four moons, and Saturn with its “handles.” The design is strikingly similar to the frontispiece of Giovanni Battista Riccioli’s Almagestum novum, which appeared in 1651 and which featured putti holding aloft these same representations of the planets, but which featured the Tychonic and Copernican cosmological systems. Riccioli, a Jesuit, devoted considerable space in his work to a comparison between those two systems, and it is noteworthy that Schott, only a few years later, went so far as to avoid even a representation of the Copernican system on a frontispiece that appears to be inspired by Riccioli’s work.28

There seems relatively little in Schott’s discussion of the telescope that one could term “magic”; instead, most attention was paid to how to construct and use the instrument. Nonetheless, the real focus of this discussion was one simple principle: the revelation of natural secrets through artifice, with Schott predicting the new and wondrous revelations that awaited further refinements of this instrument. His discussion of the microscope was significantly shorter, presumably because in 1657 the microscope had been in use for a shorter span of time than had the telescope, but here, too, Schott praised the “wondrous virtue” of its “showing the hidden structure of natural things.”29

Figure 6.2 The frontispiece to the Magia universalis.

Source: Courtesy Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology.

References to revelation certainly make sense in a volume devoted to optics. They might seem to make less sense, however, in the next volume, devoted to the magic of sound and acoustics. The extended title of this volume promised to discuss all aspects of sound, divided between theory and practice, and with the aid of analogies to vision, light, and colors, all of these things “established by practices [praxibus] and experiments.” What followed in the succeeding pages was a range of topics, from the anatomy of animals (including humans) that permits them to vocalize sounds, to ruminations on music theory and examples of machines capable of producing sound. The pervasive theme throughout was not so much the revelation of natural mysteries, but rather the exuberant intermingling of nature and artifice; over the course of this volume, the two became almost indistinguishable from one another, with the principles at work in one (such as the vocal cords) replicated and emulated in another (such as musical instruments).

Towards the end of the volume, Schott addressed “music various or rare,” noting that noises that would be considered “vile” if heard daily become more sweet when encountered but rarely: “For often the excessively discordant singing of men and animals, and the noises of instruments, more delight the ears and restore the soul than the comparable music of the angels; not that which is as pleasing as possible, but that which is more rare.”30 There is a curious similarity here with the contemporary culture of marvels that Schott was scrutinizing, and perhaps even a subtle justification for his wider enterprise in the Magia: that which is rare has a greater effect than that which is encountered daily, and so all the more reason to focus on those rarities. He also included a somewhat implausible description of “the music of donkeys”: the trick, according to Schott, lay in using male donkeys of particular natural pitches and stimulating them to bray with the urine of a female donkey, which will induce the males to make “most contented” noises that the generous might construe as a kind of music. After this came another “musical” invention, attributed to Kircher, that involved placing cats of differing sizes and constitutions in a modified harpsichord. When a key was pressed, a hammer or spike would hit a cat’s tail, causing it to yowl at a certain pitch.31

Neither of these “instruments” seems particularly magical at first glance—nor, for that matter, philosophically instructive. Indeed, Schott characterized them as examples of entertainment, with the feline harpsichord in particular designed to “move men to laughter” (Kircher had conceived of the instrument in an effort to cheer a melancholy prince of his acquaintance). Nonetheless, however light-hearted and entertaining they were, the singing donkeys and the feline harpsichord were also evocative demonstrations of the joining of artifice and nature: the vocal cords of the screeching cats became a natural analogue to the plucked strings of the conventional instrument, and in the function of one Schott’s audience came to understand the properties of the other. The inclusion in the Magia of such imaginative devices suggests that Schott was interested in spurring an equally imaginative contemplation of the possibilities inherent in the juxtaposition of nature and art, just as Kircher did throughout his own works.

Figure 6.3 Asinorum musica, or Schott’s donkey choir; below, the feline harpsichord attributed to Kircher.

Source: Courtesy Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology.

The third volume of the Magia focused on various examples of applied mathematics, or what contemporaries called “mixed” mathematics, including Centrobaryca, Mechanica, Statica, Hydrostatica, Hydrotechnica, Aerotechnica, Arithmetica, & Geometria. At first glance, the principles of hydrostatics or geometry hardly merit much praise, but Schott was so taken by their potential in producing marvels that he added as an aside, “Deservedly, this work should be called Mathematical Thaumaturgy.” The entire volume shared important similarities with the wondrous Kircherian machines in the Collegio Romano, with frequent suggestions as to how best to bemuse and startle a receptive audience with these displays of mathematical magic. At the same time, it was itself a bemusing jumble of things and ideas; in relatively short order one moved from anecdotes of the ancient craftsman Daedalus using quicksilver to animate a statue of Aphrodite to a proposed quadriga or cart that could move “without horses,” and from the devices used by Domenico Fontana to relocate a massive Egyptian obelisk on the grounds of the Vatican in 1586 to a disquisition on the possibility of moving the entire Earth (if it were made of solid gold) by applying only a single talent, or approximately 75 pounds, of force with the use of a glossocomum, a series of toothed wheels that synergistically multiply their force when used in concert.32 This last example was borrowed (without attribution) from an unpublished manuscript by Christoph Grienberger, the former mathematics professor in the Collegio Romano, and Schott’s musings on the potential power of artifice—capable of shifting the world if applied properly—stand as a poignant evocation of that famous statement of Archimedes, “Give me a lever and a firm place to stand and I will move the world.”

Schott’s unswerving faith in the potential of artifice to uncover nature’s secrets also encouraged him to repeat the rhetoric he used in the first volume of the Magia, where either nature or artifice sought to conquer the other. For example, on the subject of “mechanical magic” Schott proclaimed, “There is no Art, no Science, that more manifestly seems to conquer Nature than Mechanics.”33 In many respects, however, this entire volume of the Magia universalis is rather prosaic. While Schott was willing to describe the application of mathematics to various tasks, it comes across more as a collection of anything and everything to do with the mixed mathematical disciplines, rather than as a focused disquisition on “magic.”

The fourth and final volume of the Magia bore the title, “Thaumaturgus Physicus,” and promised to discuss everything from pyrotechnics and magnetism to curatives and chiromancy. At the heart of this volume lay an apparent dichotomy that would reappear in the later Technica curiosa, between a language of magic and mysteries on one hand and the philosophical exploration and explanation of those same mysteries on the other. This appeared, too, in the volume’s complete title, where Schott promised to discuss “all that is rare, curious, and prodigious, that is, truly magical … illustrated by innumerable examples and experiments … and either affirmed or rejected by physical reasons.”34

Thus, one finds a juxtaposition of two separate languages: one of seeming esotericism, the other of natural philosophy and, more specifically, physics. As an example, Schott turned to a Peripatetic vocabulary of qualities and propagation in his discussion of sympathetic and antipathetic magic, in an attempt to explain why disparate objects influenced one another without appearing to touch. Echoing Niccolò Cabeo almost exactly, Schott outlined three different kinds of contact: the sensible propagation of a particular species as in heating and cooling, the occult propagation of an insensible species as in magnetism, and the emission of particles or corpuscles that carried scent from substances like wine and vinegar.35 With the exception of corpuscles—branded in 1651 as philosophically unsound in the Society’s guide to teaching and curricula, the Ordinatio pro studiis superioribus—this was a standard, Peripatetic explanation for a range of typical occult phenomena. Schott then juxtaposed this, however, with the decidedly non-Peripatetic practice of dowsing for buried metals with a forked stick and a discussion of the sympathy between mercury and gold. The Magia consequently fulfilled its promise to “bring forth” the secret marvels and wonders of nature through, at least in part, attempts at philosophical explanation.

True to the earlier volumes of the Magia, Schott also mingled together nature and artifice in a variety of ways. For example, consider his discussion of “pyrotechnic magic,” which he further defined as concerned with “varied and prodigious experiments, spectacles, and machines of artificial fire.”36 His focus was not merely on artificial fire, however. Alongside descriptions and explanations of Greek fire, perpetual flames, and pulvis pyrius—literally “fiery powder,” or gunpowder—Schott included a lengthy discussion of the pulmo marinus first described by Pliny: bioluminescent jellyfish that often washed up onto shore.37 Schott thus mingled the artificial and the natural, presenting them alongside one another with the implication that the light and heat produced artificially by chemical reactions and other examples of artifice mirrored in some way the light produced naturally by marine life.

One also encounters in the Magia the same curious practice that Schott would later employ in the Technica curiosa: an insistence on referring to phenomena as mirabilia or marvels while, at the same time, rendering them comprehensible, if not commonplace, by stripping away their elements of mystery and describing their inner workings and principles in particular detail. As an example, in the Magia Schott referred to “the impenetrable nature and properties of the magnet” and also characterized the magnet as “a stupendous miracle of nature” and “the labyrinth of the philosophers.”38 A reader encountering such phrases might be forgiven for believing that Schott himself had been stymied by the labyrinthine, “impenetrable” magnetic nature, but in fact the following hundred pages demonstrated in exhaustive detail that Schott had been neither stymied nor deterred in describing the properties of the magnet and their application to a variety of tasks and spectacles.

One might connect Schott’s apparent fondness for characterizing exotic phenomena as marvels and wonders with claims that, like Kircher, Schott was doing little more than reveling in the mysteries of nature.39 Merely playing with nature’s secrets, however, would have availed Schott and Kircher nothing. By contrast, the demonstration and exhibition of nature’s secrets could have afforded them considerable intellectual notoriety in a period when numerous individuals were trying to exhibit the same things.40 Moreover, Schott could only sketch the boundaries of the natural if the hidden reaches of the world were exposed and unveiled, and thus simply leaving these things secret and unknown would accomplish very little.

Indeed, in an important sense Schott’s works fulfilled the same purpose as Kircher’s figurative and emblematic illustrations. We might look to the images Kircher included in the Magnes or the Mundus and wonder why they described phenomena and devices that either never existed or could not exist as rendered therein. If Kircher’s purpose in commissioning and including these images, however, was not to transmit accurate or “true” information about the natural world but rather to encourage the imaginative reader to contemplate the world for himself, then we can understand Schott’s project as embracing a similar set of goals. Schott was not necessarily using the Magia universalis to explain every phenomenon under consideration, particularly as at least some of those phenomena possessed only a tenuous link, if any, to genuine principles of natural knowledge.

In spite of this, however, there lay at the core of the Magia Schott’s insistence that artifice could both elevate and direct nature, a philosophy that lay very close to the experiential and experimental practices embraced by institutions like the Royal Society. The English virtuosi hoped to secure the most likely and useful knowledge of nature through active intervention and manual labor—by getting their hands dirty, to paraphrase Robert Boyle.41 Experiment was the means whereby reason could be brought to bear on sense-experiences, thereby securing the most probable knowledge of how nature worked. Schott went further still in the Magia, however; like his mentor, Athanasius Kircher, he claimed that artifice could instruct nature in its own limits, and might in turn instruct us in where those limits lie.

We have seen in previous chapters that contemporary intellectual crises involved the active redefinition of the boundaries between different kinds of things: recall the debates over the weapon salve and the efforts made to define it either as natural, supernatural, or something else altogether, or Martín del Rio’s struggles with the ontology of magic. The study of the unseen was in flux at the precise moment that Schott wrote his Magia universalis, and it is clear that the Magia was itself part of this ongoing redefinition of phenomena. When Schott juxtaposed Greek fire and gunpowder with the glowing bodies of jellyfish, his goal in doing so was not merely to contrast a natural effect with an artificial one, but to mingle both effects together and thereby encourage us to contemplate a kind of “fire” that lay somewhere along the ever-shifting line between nature and artifice, one that became less marvelous with the more particulars—in the Baconian sense—he provided. Indeed, I suggest that Schott’s project here was, in at least some sense, thoroughly Baconian: in his enthusiastic and eclectic intermingling of phenomena and objects, he was fashioning his own kind of history—not, perhaps, Bacon’s idea of “natural history,” but something novel in which innumerable particulars of nature and artifice were brought together to create a record that testified to the marvelous diversity and ingenuity of Creation.

While an excellent example of his predilection for revelation, Schott’s later Technica curiosa also underscored his commitment to artifice and experiment as part of that revelation. The full title, Technica curiosa, sive Mirabilia artis, testified to Schott’s focus on “the wonders of art,” and the title page promised that one would find a variety of arts discussed within, including “the secret, miraculous, rare, curious, [and] ingenious.”42 Moreover, in the opening pages of the Technica Schott informed his readers that

the chief purpose of the labors undertaken in these four volumes is to excite others toward the experimental philosophy. I have already shown … how greatly that style of philosophizing pleases me, which is not dependent on the subtleties of words and cunning, but which examines thoroughly the concealed heart of Nature itself and which unites “to know” [scire] with “to be able” [posse] in a happy marriage.43

It is worth noting that this marriage of knowing and doing, of contemplation and action, echoed both Schott’s talk of the marriage between art and nature in the Magia universalis and the dichotomy at the heart of Kircher’s Mundus subterraneus. Though the Technica did contain a variety of curious and ingenious things however, there was little that Schott permitted to remain secret; the “concealed heart of Nature” did not, in fact, remain concealed for long.

Indeed, though filled with a persistent rhetoric of wonders, marvels, and arcane knowledge, the Technica curiosa actually functioned as an elaborate exercise in revelation. It opened the mysterious innards of particular machines, set forth mathematical and linguistic methods of representing the natural world, and demonstrated that it could explain and expose even the most curious and ingenious of objects. After explaining so thoroughly the principles that informed these demonstrations of artifice, after laying open the machines and devices themselves and demonstrating not only how they operated but also how they explained and emulated natural processes, Schott could hardly claim with any real validity that what he described was truly wondrous or difficult to understand. His practice of offering with one hand the rhetoric of wonder and dismantling it with the other forces us as his readers to question why he might have used this language in the first place. It makes sense to link Schott’s rhetorical practices here with the evolving intellectual culture of the day. His habit of marking phenomena and objects as wonders or mysteries before uncovering their causes was a kind of staged venatio, a hunt for nature’s secrets on Schott’s own terms.44 But it also demonstrated that appearances can be deceptive: what seems to be an intractable puzzle is, instead, merely a rather prosaic philosophical demonstration, and we are left to marvel at both the mysteries of nature and the limits of our own understanding.

The Technica opened with the work of Otto von Guericke, whose experiments Schott had included in his earlier Mechanica hydraulico-pneumatica and which had made that work very popular with readers. Schott included several letters from Von Guericke in the Technica, and described in detail the man’s many pneumatic experiments, including the famous Magdeburg spheres, metallic hemispheres that, when evacuated of air, could not be separated by teams of horses pulling in opposite directions. Von Guericke and others had used this example to establish the existence and strength of the vacuum, and while Schott contented himself at first with merely describing Von Guericke’s work and subsequent conclusions, he eventually proposed his own explanations for these phenomena, after first describing the “Mirabilia Anglicana,” or “English marvels” wrought by Robert Boyle’s experiments with the air pump.

Figure 6.4 Schott’s depiction of the Magdeburg pneumatic experiment, from his Technica curiosa.

Source: Courtesy Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology.

Ostensibly committed as he was to an Aristotelian philosophy, Schott denied the existence of the vacuum in a subsequent section of the Technica entitled “A physical scrutiny of the preceding experiments,” meaning those described and illustrated in the preceding three books, all of which were pneumatic in nature.45 Schott claimed that the experiments performed with Von Guericke’s spheres, Boyle’s air pump, and Torricelli’s glass tubes had not established the existence of a vacuum because “glass has pores” through which materials could flow, and that the aether “fills every space,” including the seemingly empty chamber of the pump or tube once the air has been evacuated. He did, however, embrace a view similar to Boyle’s when he suggested that the air possessed an elastic virtue or force that might explain some of the results witnessed in these various experiments.46 Thus, here as in the earlier Magia universalis, Schott’s work was neither uncritical nor encyclopedic; it was instead a careful description of reported experiments followed by an equally careful Peripatetic analysis of the results.

In subsequent books of the Technica, Schott described “hydrotechnic wonders”—fountains, for the most part—and “mechanical wonders,” including a number of perpetual-motion machines. What was striking about Schott’s description of these wonders was the manner in which he exposed to the reader’s eye the means by which these “marvels” functioned: in the case of the fountains, for example, he included numerous illustrations that juxtaposed the fountain itself with the actual mechanisms that permitted it to work, superimposing these mechanisms onto a plain wall to indicate that they would normally be hidden from view. The accompanying text promised to explain to the reader how these devices worked (he repeated the phrase explicatio praecedentis machinae many times) and duly described the function and purpose of the many components illustrated on the preceding pages, sometimes also including instructions on how to build such machines.47

Recalling that Schott wrote his earlier Mechanica hydraulico-pneumatica, upon which he based the Technica, as a catalogue of the pneumatic and hydraulic devices in Kircher’s museum, we might interpret this particular example of Schott’s work as a similar exercise in showmanship and spectacle, bringing to a much wider audience the wonders displayed by his mentor as well as those shared with Schott himself by his numerous correspondents. He describes, for example, the Fonticulus Kircherianus, a device shaped like the two-headed imperial eagle of the Hapsburgs that vomited water from both heads. Similar examples included a device in the shape of a crayfish that, when hooked over the edge of a goblet as if trying to escape from within, sucked in water with its tail and vomited it from its mouth. Schott’s Technica thus worked to expand the boundaries of Kircher’s museum; he was propagating in print what Kircher had already sought to accomplish viva voce.48

The revelatory tone that pervaded the Technica curiosa was made explicit when Schott turned his attention to a tract written by Kircher, the Specula Melitensis Encyclica, originally produced in 1638 and thus among his first works. This “Maltese Observatory,” so-called because Kircher originally dedicated the treatise to the Knights of Malta and supposedly constructed the device on the island itself, was intended by its author to function as a “new [type of] physico-mathematical machine.” Kircher’s insistence on designating this device as an observatory—a high place from which one can see what might be otherwise obscured—is itself suggestive of its role in bringing to view numerous natural correspondences and phenomena; as he explained it, he chose the term specula because “[the principles of] astronomy, geography, hydrography, physics, and medicine are exposed to the eye.”49 Kircher claimed that his Observatory was capable of everything from charting the movements of the planets and predicting storms and winds to establishing the times and locations of future eclipses and “discovering medical agents with occult powers,” making it arguably one of the greatest examples of the revelatory powers of artifice found in any of his, or Schott’s, works.

Kircher’s Maltese Observatory operated by virtue of the correspondences between disparate things, an idea that we already know lay at the heart of his natural philosophy. Indeed, the Observatory was itself an artificial device that displayed the changing currents in the wider world, calibrated so as to detect and measure these changes and thereby permitting the learned artificer to predict future events such as eclipses and storms. Moreover, the Observatory echoed Kircher’s words to the Emperor Leopold in the Mundus subterraneus, where he promised that the text itself would work as a piece of artifice, exposing to Leopold’s eye the depths of the Earth. We should recall, however, that Kircher’s dedication to the Emperor was also layered with notions of dominion, utilization, and manipulation. The Mundus permitted its user to do more than merely observe the world; it permitted him to control it as well. The Maltese Observatory described by Kircher shared a similar purpose: those who used it did not simply observe the unseen correspondences between things, but could actively manipulate them in the production of medicines and, more broadly, of natural knowledge.

Unlike every other example of artifice described and illustrated in the Technica curiosa, Kircher’s Specula Melitensis was not subjected to analysis and explanation. Schott never tried to demystify this device for his readers as he did with the devices of Von Guericke, Robert Boyle, and others. Instead, he left us only with Kircher’s explanations, such as they were. It is possible that Schott felt himself unequal to the task of properly explicating his mentor’s project, though it is also possible that, by placing Kircher’s Encyclica at the literal heart of the Technica and leaving the elder Jesuit to speak for himself, as it were, Schott was bestowing the imprimatur of his mentor on his own project, linking his descriptions, illustrations, and experiments with Kircher’s insistence on rendering the natural world “exposed to the eye” of his readers.

Following the Specula Melitensis Encyclica, Schott went on to detail the properties of a proposed artificial language—inspired by Kircher’s 1663 Polygraphia—and claimed that such a work of art presented the best hope for “a universal key to the language of the entire world,” discussing these “written marvels” as a means of representing the natural world in its entirety.50 This constitutes another facet of revelation, for many thinkers in the seventeenth century who focused on artificial and universal languages saw them as a way of depicting the links between natural objects and thereby opening up the depths of nature to human scrutiny and understanding.51 In the final book of the Technica, Schott examined another revelatory language, the cabala, or in his words, “Cabalistic wonders, or, the Cabala of the Hebrews lucidly explained, accurately examined, and sincerely judged,”52 Following as it does books devoted to chronometric and automatic marvels, Schott’s discussion of the cabala might appear out of place at first glance, and yet the principles that he discussed actually fall into alignment with the rest of the treatise, with an emphasis on the uses of the cabala—a human art—in revealing hidden knowledge of the world, and on its status as a “secret art,” appreciated and understood only by select adepts. Schott himself chose to take a fairly neutral stance on the cabala, claiming that he could neither wholly praise nor wholly condemn it but saw both good and bad, useful and noxious joined together within it.53

Schott’s interest in the cabala is unsurprising; his mentor Kircher had a long-standing fascination with it as well.54 In turn, Kircher inherited this fascination from more than a century of Christian commentaries on the cabala, beginning in the latter decades of the fifteenth century when Giovanni Pico della Mirandola first tried to reconcile the fundamental precepts of the cabala with a Christian perspective in pursuit of a contemplative and mystical union with the divine.55 Interest in the cabala persisted well into the seventeenth century, so Schott was far from alone in devoting a portion of his Technica to this art; like many among his contemporaries, he saw in the cabala a potential means of addressing and solving existing problems that extant traditions had either ignored or were inadequate to resolve.56

For some early modern thinkers the cabala offered yet another solution to the intellectual crises of the day, an alternate framework in which they could order and understand the world. Taken in this light, Schott’s interest in the cabala as well as its placement in the Technica both make sense: as with the universal languages, the cabala offered Schott the opportunity to unlock the mysteries of nature and then make them manifest to the eyes of his readers. He first pointed to a division within the cabala between Mercava and Beresith, with the former concerned with a knowledge of divine things—“that which revolves around God, the true Creator of all things,”57 such as the various names of God and the ten Sephiroth—and the latter with natural or created things. In his definition for the Beresith cabala, Schott intriguingly presented this particular art in the same terms as those used by many to describe natural magic, as a joining of active with passive in the production of a particular, wondrous effect.58 Consequently, the cabala assumed for Schott the same potential as natural magic, another parallel drawn between the human arts and the hidden powers of nature. In concluding his discussion of the cabala, Schott noted its utility in revealing and uncovering the mysteries of the Trinity as well as the mysteries of the natural world.59

We should recall that Kircher chose to end his Magnes on a spiritual note, encouraging his readers to see the invisible force of the magnet as not merely an analogue for the mysterious power of God, but also as fodder for an imaginative contemplation of the marvels of God’s creation and His providential care for everything in it. In choosing to end the Technica curiosa with a discussion of the cabala, I believe Schott was attempting something similar. The cabala was an example of human artifice designed to illuminate the hidden mysteries of God, but so too were the air-pump of Robert Boyle and the vomiting machines of the Kircherian collection, which reified in their operation the laws and forces that governed Creation. For Schott as well as for Kircher, human artifice was important because it made visible the hidden intricacies of nature, those marvelous exemplars of God’s power and will.

Upon reaching these last pages of the Technica curiosa, early modern audiences would have found themselves informed, perplexed, but also, perhaps, inspired. Schott had taken the mysteries of artificial magic and the baroque culture of machines enshrined in Kircher’s Roman museum and laid them open time and again, revealing secrets on almost every page. At the same time, he presented his readers with a message that was surely as reassuring as it was bemusing: the secrets of nature were as vulnerable to demonstration and display as the machines exposed and dissected in the pages of his book. It was to artifice that naturalists should look to address the problems of uncertainty and mystery that still plagued natural philosophy, and there were crucial answers to be found even in the quixotic arrangement of cats in a makeshift harpsichord. It was an optimistic vision for a new kind of science that, if nothing else, deserves greater attention than it has received.

1 Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750 (New York: Zone Books, 1998), p. 220.

2 Lorraine Daston, “The Nature of Nature in Early Modern Europe,” Configurations, vol. 6 (1998), pp. 149–72.

3 Lorraine Daston, “What Can Be a Scientific Object? Reflections on Monsters and Meteors,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 52, no. 2 (1998), p. 45.

4 Daston, “What Can Be a Scientific Object?,” p. 45.

5 William Eamon, “Science and Popular Culture in Sixteenth Century Italy: The ‘Professors of Secrets’ and Their Books,” Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 16, no. 4 (Winter 1985), p. 484. See also his Science and the Secrets of Nature (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996).

6 Marcus Hellyer, Catholic Physics: Jesuit Natural Philosophy in Early Modern Germany (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), p. 7.

7 Hellyer, p. 44.

8 Gaspar Schott, S.J. (attr.), Joco-seriorum naturae et artis, sive magiae naturalis centuriae tres (Frankfurt am Mayn: Cholinus, 1667), p. 26: “Pulli caput perforare, ut vivus maneat.”

9 Gaspar Schott, S.J., Magia universalis naturae et artis; sive, Recondita naturalium et artificialium rerum scientia, cuius ope per variam applicationem activorum cum passivis, admirandorum effectum spectacula, abditarumque inventionum miracula, ad varios humanae vitae usus, eruuntur, 2nd edn (Bamberg: Joannem Arnoldum Cholinum, 1676), vol. IV, p. ii.

10 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV, Dedicatio, p. i.

11 See, for example, R.J.W. Evans, The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550–1700: An Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), p. 344.

12 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 8: “Magiae nomen in tantum apud multos his etiam temporibus versum est odium, ut eo audito horrescant aures & animi, & si quem librum eodem insignitum conspiciant, explodendum confestim, ac flammis devovendum judicent.”

13 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, pp. 8–9: “Et ut quod res est, fatear, refixi aliquando Epigraphen Magiae, eiusque loco Thaumaturgum Physico-Mathematicum reposui …”

14 Alan Chambers, “Intermediate Causes and Explanations: The Key to Understanding the Scientific Revolution,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, vol. 43, no. 4 (December 2012), p. 554. See also Peter Dear, Discipline and Experience: The Mathematical Way in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 168–79.

15 Martha Baldwin, “Alchemy and the Society of Jesus in the Seventeenth Century: Strange Bedfellows?” Ambix, vol. 40, part 2 (July 1993), p. 59.

16 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, Dedicatio, p. i: “Artis et Naturae Magia Scientiarum omnium apicem, Artium florem, occultorum scrutatricem, mirabilium effectricem, cui artes omnes, omnes famulantur scientiae …”

17 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, Prologus Encomiasticus ad Lectorem, p. iii.

18 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. iv.

19 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. vi.

20 Athanasius Kircher, S.J., Mundus subterraneus, 3rd edn, vol. II (Amsterdam: Joannem Janssonium & Elizeum Weyerstraten, 1678), p. 9.

21 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 9.

22 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 19: “Naturalem Magiam appello, reconditam quandam arcanarum Naturae notitiam, quaererum singularum naturis, proprietatibus, viribus occultis, Sympathiis ac antipathiis cognitis, res rebus, seu ut Philosophi loquuntur, activa passivis, suo tempore, loco, & modo applicantur, & mirifica quaedam hoc pacto perficiuntur, quae causarum ignaris praestigiosa, vel miraculosa videntur.”

23 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 22: “Artificialem Magiam appello, artem seu facultatem mira quaedam perficiendi per humanam industriam, adhibendo ad id varia instrumenta.”

24 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 5: “Parastaticus est, sive de prodigiosis repraesentationibus rerum à Natura & Arte factis; quem in finem variae ac prorsus admirabiles repraesentationes à Natura facte in aëre, in montibus, in rupibus, lapidibus plantis, aliisque rebus afferuntur. Et nè Artem Natura vincere videatur, eadem etiam, & magis prodigiosa, saltem magis concinnè ac jucundè, per Artem repraesentare docemus.”

25 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 488: “De Magia Telescopica, sive, De fabrica, usu, et effectu prodigioso Telescopii & Microscopii.”

26 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 491.

27 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, pp. 492–3.

28 On the strong links between Jesuit astronomy and the system of Tycho, see Kerry V. Magruder, “Jesuit Science After Galileo: The Cosmology of Gabriele Beati,” Centaurus, vol. 51 (2009), pp. 189–212; Allan Chapman, “Tycho Brahe in China: The Jesuit Mission to Peking and the Iconography of European Instrument-Making Processes,” Annals of Science, vol. 41 (1984), pp. 417–33.

29 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. I, p. 536: “De Virtute mirabili Microscopiorum, in rerum naturalium occulta constitutione ostendenda.”

30 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. II, p. 371: “Saepe enim absoni admodum hominum & animalium concentus, Instrumentorumque soni, plus aures delectant, animum recreant, quàm Musica Angelicae aemula; non quòd illa quàm haec suavior, sed quòd rarior.”

31 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. II: “Asinorum Musica,” pp. 371–2; the cat harpsichord, pp. 372–3. For more on the latter invention, see Thomas L. Hankins, “The Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel; Or, The Instrument That Wasn’t,” Osiris, 2nd series, vol. 9 (1994), pp. 141–56.

32 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. III: on Daedalus, see p. 273; “Quadrigae sine hominum aut jumentorum trahentium ope per vias agitate … quae sine equis antrorsum et retrorsum progrediebatur,” attributed to “D. Georgius Philippus Harstorfferus,” p. 259; for a description of the procedures used to move and erect the obelisk, see p. 297; for Schott’s musings on the possibility of shifting the Earth, see pp. 236–41.

33 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. III, p. 88: “Nulla enim Ars est, nulla Scientia, quae evidentiùs Naturam superare videtur, quàm Mechanica.”

34 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV. The full title of the volume reads: “Thaumaturgus physicus, sive Magiae universalis naturae et artis … Quibus pleraque quae in Cryptographicis, Pyrotechnicis, Magneticis, Sympathicis ac Antipathicis, Medicis, Divinatoriis, Physiognomicis, ac Chiromanticis, est rarum, curiosum, ac prodigiosum, hoc est, vere magicum, summa varietate proponitur, varie discutitur, innumeris exemplis aut experimentis illustratur, solide examinatur, & rationibus physicis vel stabilitur, vel rejicitur.”

35 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV, p. 367.

36 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV, p. 97: “De Magia Pyrotechnica; sive, De variis ac prodigiosis artificialium ignium experimentis, spectaculis, ac machinis”

37 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV: for Greek fire, see p. 122; on perpetual flames, p. 150; pulvis pyrius, p. 182. On the pulmo marinus, see p. 102.

38 Schott, Magia universalis, vol. IV, p. 225.

39 Evans, The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, p. 344.

40 See, for example, Eamon’s Science and the Secrets of Nature, which records numerous examples of early modern thinkers and their attempts to exhibit nature’s secrets to a wide range of audiences.

41 Steven Shapin, “The Invisible Technician,” American Scientist, vol. 77 (1989), pp. 554–63.

42 Gaspar Schott, S.J., Technica curiosa, sive Mirabilia artis, libris XII comprehensa …, 1st ed. (Nuremberg: Johannis Andreae Endteri & Wolfgangi Junioris Haerdum, 1664), title page: “Libris XII comprehensa; Quibus varia Experimenta, variaque Technasmata Pneumatica, Hydraulica, Hydrotechnica, Mechanica, Graphica, Cyclometrica, Chronometrica, Automatica, Cabalistica, aliaque Artis arcana ac miracula, rara, curiosa, ingeniosa, magnamque partem nova & antehac inaudita, eruditi Orbis utilitati, delectationi, disceptationique proponuntur.”

43 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 5.

44 For more on the early modern concept of the venatio, see Paolo Rossi, Philosophy, Technology, and the Arts in the Early Modern Era, trans. S. Attanasio (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), p. 42.

45 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 214: “Scrutinium physicum praecedentium experimentorum.” For early modern and, particularly, Aristotelian objections to the vacuum, see Edward Grant, Much Ado About Nothing: Theories of Space and Vacuum from the Middle Ages to the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

46 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 295: “Aëris elastica vis experimentis probatur.”

47 For example, p. 361 describes how to build an ornate fountain—Constructio Machinae—illustrated on the facing page.

48 Vomiting machines were, apparently, a central feature of Kircher’s collection in Rome; see Michael John Gorman, “Between the Demonic and the Miraculous: Athanasius Kircher and the Baroque Culture of Machines,” in Daniel Stolzenberg, ed., The Great Art of Knowing: The Baroque Encyclopedia of Athanasius Kircher (Stanford: Stanford University Libraries, 2001), pp. 59–70.

49 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 428.

50 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 505.

51 This view was held by one of the foremost universal language theorists of the seventeenth century, John Wilkins; see his Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (London, 1668). For more on sevcenteenth-century universal language schemes, see M.M. Slaughter, Universal Languages and Scientific Taxonomy in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); James Knowlson, Universal Language Schemes in England and France, 1600–1800 (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1975).

52 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 896.

53 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 1019.

54 Daniel Stolzenberg, “Four Trees, Some Amulets, and the Seventy-Two Names of God: Kircher Reveals the Kabbalah,” in Paula Findlen, ed., Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything (New York: Routledge, 2004), pp. 143–64.

55 Brian P. Copenhaver, “The Secret of Pico’s Oration: Cabala and Renaissance Philosophy,” Midwest Studies in Philosophy, vol. 26 (2002), pp. 56–81.

56 William J. Bouwsma, “Postel and the Significance of Renaissance Cabalism,” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 15, no. 2 (1954), p. 232. See also Philip Beitchman, Alchemy of the Word: Cabala of the Renaissance (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998).

57 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 961: “illa enim circa DEUM verum omnium conditorem.”

58 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 990: “Alii in entium naturalium ordine & connexione mutuam, quam inferiora mediis, media secundis conjuguntur; vel potius in eiusmodi ordinis cognitione eam constituunt: unde ex analogia & proportione singulorum ad alia, per applicationem activorum cum passivis mira se praestare posse putant.”

59 Schott, Technica curiosa, p. 1044.