An Uncommon Book of Common Prayer

“. . . and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice,

“without pictures or conversations?”

—Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

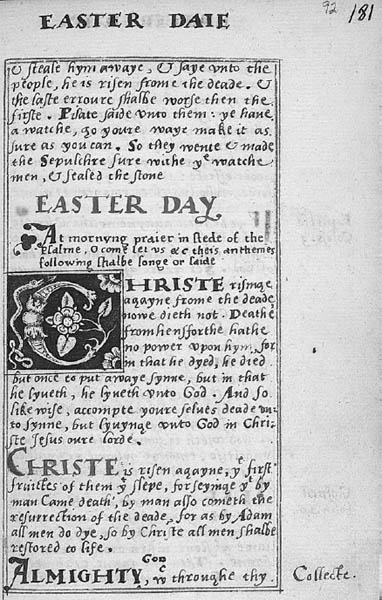

Alice’s question applies not just to Victorian storybooks but also to Elizabethan prayer books, and this chapter offers one of them as an object lesson, a curious devotional volume that not only contains pictures and conversations but raises a series of searching questions about the uses of books in the English Renaissance. It is a manuscript copy of the entire printed Book of Common Prayer and Psalter—the two texts that together formed the established script for the ritual conversations between a minister and his congregation, on the one hand, and between individuals and God, on the other. It was made in the early 1560s and it features an elaborate decorative scheme drawing on the visual conventions of both printed books and manuscripts. The most striking feature (at least at first glance) is the ornamental initials that adorn almost every page, including some seventy capitals devised in the style of woodcuts from contemporary printed books (Figure 23), and another seventy illuminated letters that were recycled from three or more late medieval manuscripts using scissors and paste (Figure 24).

Even these superficial details are sufficient to pose a number of immediate questions, few of which can be answered with confidence but all of which are worth exploring. Why would someone bother to make—or have made for them—a manuscript copy of the recently printed and readily available Book of Common Prayer and Psalter (and its 598 pages of closely written text could not have been either easy or cheap to produce)? Who might have wanted a book that looked like this, and who might have wanted them not to want it? In what spaces, and for what activities, was it intended to be used? Where might it have been produced, and was it the work of an amateur or a professional, a single scribe or a proper scriptorium? Where did the appropriated initials come from and what did they mean to the person(s) who owned this book—did they just think they looked pretty and/or holy, or did they carry specific (and even charged) associations with the not-so-distant medieval past or with the Catholic devotional culture that had only recently been forced back underground? What kind of religious and textual mentality, in other words, could account for a book like this, and how does it fit into our received narratives of the transition from script to print and from Catholicism to Protestantism?

Figure 23. A manuscript Book of Common Prayer (1560–62, RB438000:354): typographical initial featuring rose and serpent. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Figure 24. A manuscript Book of Common Prayer (1560–62, RB438000:354): plundered initials from late medieval manuscripts. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, RB438000:87.

James R. Page’s Used Prayer Books

This volume caught my eye as I was making my way through the collection of prayer books and related materials assembled by James R. Page, one of the Huntington’s trustees and one of the directors of Union Oil of California. When the Page Collection was presented to the Huntington Library after Page’s death in 1962, its annual report called it “The outstanding special acquisition of the year”; and it remains a rich and relatively unknown resource for scholars interested in the production and reception of devotional books between the fourteenth and twentieth centuries.1 Since I was more interested in the reception than in the production of religious books—and particularly in the marks left behind by early readers—I was pleasantly surprised to find that, unlike most of his fellow collectors, Page preferred books that are (as he himself put it in a passage I will consider more fully in chapter 8) “enlivened by the marginal notes and comments made by the many people . . . through whose hands they passed.”2 By pursuing—or at least not shying away from—customized and quirky books, and even those considered by others to be “imperfect” or “soiled,” he not only found some extraordinary bargains but did a great service to future historians of past reading. The majority of Page’s acquisitions from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries preserve contemporary signatures and annotations, with examples of most of the things English Renaissance readers did with, and to, their liturgical and devotional books.

Many different kinds of traces testify, once again, to many different forms of interaction between books and readers—physical and intellectual, social and spiritual, political and personal.3 There are ownership notes of various kinds, from simple signatures to elaborate formulae. In 1692, for instance, John Carter inscribed his 1617 Psalter with a conventional couplet, “John Carter his Booke[,] god giue him grace therein to look”; but instead of going on to offer rhyming insults aimed at the enemies of the English Crown or to warn potential thieves (as these notes typically did) he went on to express concerns that were altogether more cosmic, continuing “if a man shall die shall he liue again[:] all the dayes of my Apointed time will I waitt until my change cometh and though after this skinn worms destroy this Body of mine yett in my flesh shall I see god whome mine eyes shall behold and not another”—a close paraphrase of Job 19:26–27.4 There are title pages and flyleaves covered with prayers, pious phrases, recipes, notes for further reading, and records of payments: the flyleaves bearing John Carter’s ownership inscription also contain a reminder that “Wee are to remember our end,” a memorandum that “I paid to Mr Toringue of Warwick for Binding of This Booke—0–4-6,” and a nostrum for an unspecified ailment combining “one dram of . . . sulfur” and two ounces of “the sirrup of violets.” There are family histories, which were very common in the period’s books (and not just its Bibles, as we have already seen). In a 1619 Book of Common Prayer, for instance, Giles Hungerford used a flyleaf at the front of the volume to record his marriage to “my most deer and loveinge wiefe” Elizabeth in 1624, and then her departure from “this wretched World” in 1632. One year later he literally turned over a new leaf: on a blank page at the back of the book he documents his second marriage to “Ione [i.e., Joan] my deere and loveinge wiefe” and records the birthdates, names, and godparents of the four children she bore him over the next five years.5

Several volumes preserve the efforts of the English Crown to propagate the new faith, along with the efforts of individual readers to advance or resist it. There is a copy of the Thirty-nine Articles, printed in 1571 and used to document the public subscriptions to the articles in six different parish churches between 1579 and 1672 (including the church of Conington in Huntingdonshire in 1603, where Robert Cotton and William Camden were among the witnesses, having fled London to escape the plague).6 There is a copy of the ecclesiastical constitutions of 1599 bound with the Constitutions and Canons Ecclesiastical of 1640, heavily annotated by Thomas Hall—a spirited preacher, polemicist and book collector who was imprisoned five times during the Civil War and finally ejected from the Anglican Church in 1662.7 His marginal outbursts on the subject of synods will suggest why. On the title page to the second work he has written “That Synods may erre & that fouly to, this of 1640 proves with a witnesse,” and at the end of the text he has written a scathing critique in punning Latin:

Quid Synodus? Nodus. Patrum chorus, integer? Aeger. Conventus? Ventus. Sessio? Stramen. Amen.

[What is a Synod? A knot. A healthy chorus of fathers? Diseased. An assembly? Wind. A sitting? Scattered straw. Amen.]

There is a copy of the 1639 Book of Common Prayer with an early eighteenth-century transcription of John Cosin’s manuscript annotations in the so-called Durham Book, described by G. J. Cuming as the first draft of the revised prayer book of 1661.8 And there is a copy of the 1636 Book of Common Prayer which has been interleaved, allowing a learned reader named William Bullock to compose a detailed commentary on the English liturgy in the early 1660s, drawing on a wide range of historical sources and often providing parallel passages in Latin and Greek.9

There are countless examples of added color, in the form of rubrication and limning: the addition of red ruling around the printed text was a particularly common practice in prayer books, drawing in the eye and bounding the text, marking the margins off as a separate zone.10 This would have been executed by printers and binders as well as readers, and may have been an attempt to compensate for the relative disappearance of rubrication from English liturgical books.11 As with the Bibles surveyed in the previous chapter, not a few of these volumes evidently served as coloring books for children (with or without the permission of their parents): coats of arms and other visuals are often embellished. And there are eleven embroidered bindings of various sizes, some featuring velvet backgrounds, metallic threads, and delicate depictions of King David or Adam and Eve.12

There are useful reminders of the fact that many books outlived the contexts for which they were originally produced, remaining meaningful and/or useful to readers who were willing to update them. There is a copy of the Ordinal section from the 1559 Book of Common Prayer that was both annotated and emended during the reign of James I: small slips of paper were carefully pasted over all references to Elizabeth and replaced with new text referring to James—even changing every instance of “she” to “he” and “her” to “his.”13 More typical and consequential are the modifications that can be found in pre-Reformation prayer books still in use after the Reformation. Martha Driver has recently described the survival of religious books that have been selectively defaced to remove material that was now thought objectionable (particularly texts addressed to the pope, St. Thomas Beckett, or the Virgin Mary):

it is interesting to note the number of medieval books . . . which, though censored, defaced and annotated by later Protestant commentators, survive to this day, though some have been so badly damaged that they are scarcely decipherable. . . . One answer might be that books continued to be valued as comparatively expensive commodities that were worth keeping. But another answer might be found in the complex relationships Protestantism had with Catholicism. . . . English owners of books deemed heretical were generally circumspect in their emendations, keeping the books and presumably continuing to use them while crossing out only the offending texts and, much less often, pictures. . . . Perhaps . . . we can also detect an impulse to preserve the medieval past while emending texts and images to fit contemporary religious and political trends in the early years of the Reformation.14

Among the prayer books at the Huntington with similar modifications is an interesting 1545 Primer (Figure 25) in which the Ave Maria and related prayers have been scored through and marked “Vacat” [leave out]. This volume was evidently owned by someone in the royal household—perhaps by the “John Norton bocher” whose name appears in the financial records preserved in the blank leaves, which include payments for “haye for the kinge” and “wheate for the kinge.”15

Finally, the Page Collection contains two examples of the “experiments in mixed media” that were common in the early years of printing, particularly in devotional contexts. In her pioneering account of this period of “cross-fertilization,” Sandra Hindman has surveyed what she describes as “the vast middle ground between the manuscript which copies a printed book and the printed book which simulates its manuscript model [where] there is much material which relates to both media while conforming to neither.”16 She is particularly interested in hybrid confections that combine manuscript texts and printed images—some removed from their original contexts and some apparently produced for individual use, to be hung on walls or inserted into customized devotional collections.17 Such examples, she suggests, are “nearly endless and they bespeak, in the words of [Curt] Bühler, ‘one of the most curious and confused periods in recorded history.’ ” The work of recovering and interpreting such books is still in its early stages, but “what is already obvious . . . is the continual interchange between the hand- and machine-produced book . . . marking the latter half of the fifteenth century as a period of intensive experimentation.”18

Figure 25. Censored prayers in a 1545 primer (RB62311–2). By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

There is ample evidence to suggest that this period of experimentation should be extended through the latter half of the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth, at least: while the discrete conventions of the two media were clearly worked out by the 1510s or 1520s, certain contexts allowed the models to mingle and the formats to mix throughout the early modern period.19 Perhaps the most familiar examples from recent scholarship are the scribal communities that flourished as religious communities went underground—the exiled Marian Protestants, for instance, or the Elizabethan recusants.20 The Page Collection contains a typical volume produced by an unidentified English Catholic in the early 1570s, combining a manuscript copy of Catherine Parr’s prayers and meditations from 1541 with a series of fifty-four woodcuts and engravings (most of them hand-colored), depicting the Passion, Evangelists, saints, and spiritual exercises. Structured around a brand new set of engravings, evidently acquired from the Continent, the manuscript also contains xylographic prints at least a century old, giving this collection the look of a personalized devotional scrapbook.21

An Uncommon Book of Common Prayer

This takes us, at last, to item 354 in the Page Collection.22 Page bought this item from the booksellers Meyers & Co. in 1952, for the shockingly low price of £35. The sale catalogue described it as “[The Book of] Common Prayer, with the Psalter. Manuscript, very beautifully written, with illuminated Capitals; half morocco 8vo. 1562.” Implying that the illuminated initials were produced at the same time and by the same scribe as the rest of the writing, this description makes the volume sound more conventional (and straightforwardly “beautiful”) than it is, glossing over the jarring juxtapositions and vexing bibliocultural mysteries contained within its covers. Between 1560 and 1562, then, someone copied out the entire text of the Book of Common Prayer and Psalter—and while there are very few clues about the identity and location of the volume’s maker(s) and user(s) we can be fairly certain about the dates of production. First, the dates 1560, 1561, and 1562 appear in several places, worked into the decorative initials. Second, the separate title page for the Psalter is dated 1562. And third, the standard thirty-year almanac in the front of the book runs forward from 1561 instead of 1559. After the almanac and calendar (which evidently derive from the revised Book of Common Prayer of 1561), the content follows the wording of the first Elizabethan edition of 1559 very carefully. The order of the preliminary sections does not, however, exactly match any of the surviving copies I have seen of either edition; and both the spelling and the layout are thoroughly different from all known printed exemplars.

The first surviving section, the full text of the Act of Uniformity, not only prevents us from jumping to the immediate conclusion that this is the prayer book of a closet Catholic opposed in principle to the new Protestant settlement but effectively captures the hybrid quality of the textual presentation. The opening initial W combines the decorative foliation found in printed woodcuts and engravings (within the frame of the letter) and in illuminated manuscripts (along the adjacent margin). The extensive use of red ink for emphasis also draws on the rubrication common in medieval manuscripts; but the layout of the text throughout follows the models established by printers—though, again, it does not match the layout of the texts being copied. The end of the preface, for instance, follows a standard typographical layout featuring tapered and centered text and completed with a triangle of asterisks. This configuration is very commonly used to mark the end of sections in printed books; it does not, however, appear at this point in the printed Book of Common Prayer. So unless this is a copy of a printed exemplar that has since disappeared (which is not impossible, given the relatively low survival rates of these early editions), we appear to have a scribe who has assimilated the design conventions of both printed books and manuscripts, deploying them separately or in combination with a surprisingly free hand.

He also exercised considerable latitude in the design of the mock-printed initials. These are usually found in the same place as cut or engraved initials in the printed Book of Common Prayer, but they are never directly copied from them—and I have not, in fact, found a single example which offers a definite source for the initials found in the manuscript. Some of these initials are extremely crude, suggesting either experiments that failed or copies that went horribly wrong; and grotesque designs like the initial A covered in and surrounded by eyes go some way toward capturing the fanciful air of the entire production (Figure 26). But some of them required skills of design and execution that put this production well beyond the reach of a casual penman or artist (Figure 27). This aspect of the decoration is so far from consistent, in fact, that it is difficult to characterize the scribe as either amateur or professional—and indeed suggests that more than one person had a hand in its production. The hand of the text is careful but not particularly accomplished, by sixteenth-century scribal standards; and it is entirely possible that the scribe (or, perhaps, one or more of the volume’s owners) tried to fill in some of the blank spaces for decorated initials left after as many as possible were filled with professional work and with the available initials cut out from medieval manuscripts.23

As for the recycled medieval initials, they are not particularly old or beautiful—as decorative capitals go. They fall into several distinct styles, most of which can be roughly dated and located.24 The oldest style dates from the mid- to late fifteenth century, and it almost certainly derives from a French manuscript. The rest of the letters date from the late fifteenth century or early sixteenth century, and they are either from Flemish manuscripts or from English manuscripts designed to look like Flemish manuscripts. There is also one capital A in bright blue ink and on paper rather than parchment, and it was probably borrowed from a sixteenth-century English manuscript—or quite possibly from a rubricated initial added to an early printed book. Very few of the initials contain a pictorial component, but one small O with a bust of Christ displaying his wounds was clearly associated with the cult of the wounds of Jesus and was probably removed from the associated rubric in a book of hours (Figure 28). Eamon Duffy suggests that this cult was one of the most popular religious movements in late medieval Europe and was actually gaining adherents in England “up to the very eve of the Reformation.”25 While our scribe was not necessarily invoking the Catholic liturgy with this initial, he does seem to have thought about the content of the image: it is probably more than coincidence that this particular initial is placed at the beginning of the Collect for St. Bartholomew, next to the text, “By the handes of the Apostells, were many signes & wonders shewed emonge the people” (144r).

I have been using male pronouns until now to refer to the producer(s) and user(s) of this book, but I would like to entertain the possibility not simply that the volume was used by a woman but that a woman also played an important role in its creation—as with so many of the books of hours that form its most direct precursors. The “return of the reader” to literary and historical studies over the last two decades has involved a more or less adversarial division between those who study “imagined,” “implied,” or “ideal” readers and those who study the traces of “real,” “actual,” or “historical” readers.26 In piecing together the clues contained in this unusual volume, I have developed a strong sense of what might be described as the “imagined actual reader”; and the implication of the evidence—the choice of italic rather than secretary hand, the use of recycled goods, the preference for a devotional textuality that combines the verbal and the visual—points in many ways toward the material world of the early modern woman. There are striking similarities with the medieval religious books associated with female patrons and owners, on the one hand,27 and, on the other, the domestic practices of the genteel Georgian women studied by Amanda Vickery and of the much less genteel colonial women studied by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich.28

Figure 26. A manuscript Book of Common Prayer (1560–62, RB438000:354): amateur mock-woodcut initial. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Figure 27. A manuscript Book of Common Prayer (1560–62, RB438000:354): professional mock-woodcut initial. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Figure 28. A manuscript Book of Common Prayer (1560–62, RB438000:354): recycled initial with Christ displaying wounds. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Whether or not it was created by or for an Elizabethan woman, it should already be clear that it is not just facile wordplay to describe this book as “uncommon.” It is obviously unusual or special, but we can be more precise and more historically nuanced than that. First and foremost, the various elements brought together in this volume are extremely rare and I am not aware of anything else quite like it from the Elizabethan period. I have come across one other contemporary manuscript copy of the Book of Common Prayer (sans Psalter), produced in 1576. It is now housed at the Folger Shakespeare Library and was produced either by or for Robert Heasse, curate of St. Botolph without Aldgate in London, whose initials are found in many places.29 It also features a vivid decorative scheme, with elaborate (if amateurish) ornamental borders stuffed with Tudor roses—but there are no medieval initials or any other added elements of any kind.

Second, as a manuscript—which is to some extent inherently customized and privatized—this volume cuts against the very nature and purpose of the printed Book of Common Prayer. The text played a central role (alongside the Bible and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs) in the Protestant program of using print not simply to make the word of God a matter of public ownership but to do so in a standardized, centrally sanctioned form—and the fact that so many of its key features and phrases remain in use to this day suggest how successful the campaign was: indeed, John Booty has suggested that its impact on the English language was deeper and more lasting than the King James Bible.30 By being required at every church, which all subjects were forced by law to attend every week, the new prayer book was designed to be common in several early modern senses.31 Like the new English books designed for private devotion and spiritual instruction that sold in vast quantities, the Book of Common Prayer was deemed, in the language of John Daye’s popular 1558 collection, the Pomander of Prayer, “meet . . . to be used of all degrees and estates.”32 Furthermore, it was intended to replace the Catholic primer’s range of local liturgical structures (or uses, as they were known). As the preface to the first reformed prayer book of 1549 put it, “And where heretofore there hath been great diuersitie in saying and synging in churches within this realme: some folowyng Salsbury [or “Sarum”] vse, some Herford vse, some the vse of Bangor, some of Yorke & some of Lincolne: Now from henceforth, all the whole realm shall haue but one vse.” And finally, the Book of Common Prayer was part of the Protestant church’s strong emphasis on the public and communal nature of the devotional performance.33 In her recent account of the culture of common prayer, Ramie Targoff argued that “in designing the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas Cranmer and his fellow reformers actively sought to create a liturgical practice that did not accommodate personal deviation” (my emphasis). While this may be too strong a formulation, it is certainly the case that the strong resistance by nonconformists focused on the “imposition of a mechanical and artificial practice that inhibit[ed] devotional freedom”—and this was the complaint that Richard Hooker addressed in the first systematic defense of the Anglican approach to common prayer (in book 5 of his Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity [1593]).34 And it is also true that there were plenty of more appropriate printed prayer books to be turned into a customized manuscript with medieval associations—including Reformed, English versions of the traditional primer or book of hours and any number of Protestant anthologies of private prayers.

So what kind of use might our manuscript have been intended for, and to what extent does it represent the kind of textual and devotional deviation that Cranmer and his successors wished to suppress? Since the scribe included most of the prompts for public performance—including the speech headings for the priest and the rubrics that Booty has aptly described as “stage directions indicating what the actors . . . are to do in relation to the words”—was this text meant to be used for personal or domestic prayer, serving as the script for a liturgical closet drama? Or was it supposed to be taken to church, where the owner and perhaps the members of his or her family could follow along with the public service?

If so, then the most uncommon feature of all in the volume—the illuminated initials harking back to the aesthetic and devotional models of the medieval manuscript prayer book—might well have attracted the attention of their neighbors, if not the suspicion of the authorities. In the preceding chapter I mentioned the iconoclastic drift of the Protestant reformers, part of their general preference for a purified printed word that could replace traditional images as objects of veneration and edification. The defining moment came in 1549, the year of the first English Book of Common Prayer, when King Edward VI and his ministers were so exercised by the persistence of traditional devotional practices that they issued a royal proclamation ordering the destruction of religious images and (more important for our purposes) the confiscation of all old service books—including “all antiphonaries, missals, grails, processionals, manuals, legends, pyes, porcastes, tournals, and ordinals, after the use of Sarum, Lincoln, York, Bangor, Hereford, or any other private use, and all other books of service, the keeping whereof should be a let to the using of the said Book of Common Prayer.” If the sweeping nature of this prohibition is shocking (especially when we consider that it was issued a full decade before Rome had published its first index of prohibited books), so was the intended treatment of confiscated volumes: “you should take the same books into your hands, or into the hands of your deputy, and them so deface and abolish, that they never hereafter may serve either to any such use as they were first provided for, or be at any time a let to that godly and uniform order which by a common consent is now set forth.”35 This act may, in fact, explain why there were medieval manuscripts available for cutting up, or perhaps caches of colorful initials that had already been snipped from contaminated texts.

Christopher de Hamel has called the Reformation “the great heighday of the use of cut-out leaves of manuscripts as sewing-guards, flyleaves, and as wrappers of bookbindings,” citing John Leland’s complaint to Thomas Cromwell (in 1536) that “cuttings from ancient manuscripts were being used by iconoclasts to clean their shoes and candlesticks, and for sale—‘to the grossers and sope sellers, and some they sent ouer see to ye bookbynders . . . at tymes whole shyppes full.’ ”36 And although the act of Edward VI was repealed by Queen Mary and was not revived by Queen Elizabeth, Henry Gee explains that “the provisions were [still] observed in some places without such legal re-enactment. The Lincoln return proves that the books were, as a rule, destroyed in 1559.”37

Might the creator of our manuscript him- or herself been given access to books called in by the ecclesiastical or civic authorities, or had they come down to him or her within his or her family? Were the initials salvaged from a heap of books destined for the flames, or were they cut out of family heirlooms that no longer had a comfortable place in the Protestant home? In the first case, the reuse of the initials might have been a defiant act of preservation; in the second, it might have been the by-product of a compliant act of abolition. The fact that the text contained all the right words and none of the wrong ones (including the Act of Uniformity), and that the Tudor rose features prominently in its decorations, suggests that it might have belonged to a Protestant with traditional tastes in book design rather than a church papist sneaking the old religion in through the back door. Either way, to the extent that the recycled initials turn the Book of Common Prayer back into a book of hours, they might have been sufficient to get its user in trouble—though readers of the Bishops’ Bible had to get used to satyrs with erections, and a large initial C used in the 1615 Book of Common Prayer depicts Jove with Ganymede in his lap. Both the size and the setting would have been important—smaller images were often untouched while larger ones were excised, and both Lutherans and Laudians would have been more tolerant of “idolatrous” images.

And while modern readers would tend to associate the cutting up of old books—especially those of a religious nature—with the destructive zeal implied in the “defacing and abolishing” called for by the 1549 act against old prayer books, the use of scissors and paste was by no means inherently sacrilegious in the sixteenth century. It played a more central role in Tudor and Stuart textual culture than we have tended to realize, and is in fact part of a very long tradition of cutting and pasting with the best and even holiest of intentions. It extends back into the Middle Ages: Stella Panayotova has identified an early fifteenth-century Wycliffite Bible featuring marginal illustrations cut from a twelth-century Magna glossatura.38 It continues in the early age of print: alongside his role in editing the great Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, the humanist physician Hartmann Schedel pasted many early printed images into albums, adding text around them and sometimes coloring them;39 and Mary Erler’s important account of “Pasted-In Embellishments in English Manuscripts and Printed Books” examines a series of examples from the first half-century of print culture in England. In Erler’s account, religious texts in this period are far from immune to such radical modification: prayer books were evidently among the most common recipients of visual embellishment with components taken from other texts.40 Indeed, Ursula Weekes suggests that this sort of textual modification was long associated with the devotional work of women in religious communities. Among her examples is a striking book of hours in Middle Dutch, written about 1470, with a series of engravings sewn onto the parchment leaves using red and green silk thread—turning “the relevant folios into three dimensional, embroidered objects.”41

Such practices were not only alive and well in the reign of Charles I but they were taken to a new level by the women of Nicholas Ferrar’s Anglican lay community at Little Gidding, whose famous biblical “concordances” or “harmonies” formed an important part of their daily devotional routine. These exquisite volumes were composed by cutting several copies of the four Gospels into separate lines, phrases, and even single words, and then pasting them into a new order to form a unified, continuous story—which was then illustrated with images gathered from various sources (some of which were, in fact, composed of parts of several prints cut up and rearranged to form a new whole).42 By 1633, word of these “rare contrivements” had reached the king himself and he asked to have one sent to him. After many months of silence, Charles sent one of his men to the anxious Ferrar, and he reported that the king liked it so much he had annotated it in his own hand—and would only agree to return it if they “would make him one for his daily use.” Ferrar agreed and the king’s man returned the borrowed work, and the household marveled not just at the presence but also at the nature of the king’s marginalia: “The book being opened, there was found, as the gentleman had said, the king’s notes in many places in the margin; which testified to the king’s diligent perusal of it. And in one place, which is not to be forgotten . . . having written something . . . he puts it out again very neatly with his pen. But that, it seems, not contenting him, he vouchsafes to underwrite, I confess my error: it was well before (an example to all his subjects): I was mistaken.” The royal commission was completed within a year and it pleased the king so much that he immediately requested a second volume, a harmony this time not of the Gospels but of the stories of biblical kings. When it finally arrived, Charles declared it one of his prize possessions: “I will not part with this diamond, for all those in my jewel-house. For it is so delightful to me, and I know the virtues of it will pass all the precious stones in the world. It is a most rare crystal glass, and most useful.”43

As this story suggests, the physical skill and visual ingenuity involved in the Little Gidding volumes are exceptional—but they hark back to the textual productions of late medieval nuns and anticipate the later craze for extra-illustrated religious and historical books44 as well as Thomas Jefferson’s attempt to cut and paste his way to a better Bible.45 More important, they are very much of a piece with the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century vogue for creating hybrid miscellanies of printed and manuscript fragments. Weekes, Driver, Erler, and other scholars of early engraving have documented the widespread production of printed images to be inserted into other texts—both written and printed. And in his account of the prison notebook compiled by the Yorkshire Royalist Sir John Gibson during the Civil War, Adam Smyth observes that while “several scholars have turned their attention to handwritten additions to printed books . . . the related early modern practice of inserting, pasting or binding printed pages [and other textual extracts] . . . has been largely overlooked.”46

The cutting up of initials and other ornamentation from medieval manuscripts—to create visual samplers or redeploy them in new compositions—reached new heights (or depths, depending on your perspective) in the nineteenth century. The most spectacular example is undoubtedly that of the Victorian critic, collector, and provocateur John Ruskin, who subjected his considerable collection of medieval manuscripts to some fairly extreme treatment:

Use was his only criterion and books which had ceased to interest him were sold or given away. The margins of a page, he thought, were not provided to frame the text, but as a place for him to make notes and textual criticism. . . . And if any book was too tall to fit its shelf, Ruskin did not hesitate to take a saw and cut off the head and tail! . . . The manuscripts did not stand safely on his shelves. He annotated them copiously or broke them up, framing some pages, giving others away to his friends or students. “Missals,” he wrote, “for use, not for curiosities.” On 30 December 1853 he noted in his diary “cut some leaves from large missal”; on 1 January “put two pages of missal in frame,” and two days later, “cut missal up in evening—hard work.”47

Sandra Hindman and Nina Rowe’s recent exhibition “Medieval Illumination in the Modern Age” puts Ruskin’s (ab)used books in context. Among their exhibits are the Burckhardt-Wildt album, a scrapbook of ornamental strips excised from the foliated borders of illuminated manuscripts and pasted into shapes such as classical urns, and another album from the household of Phillip A. Hanrott in which initials cut from a Carmelite missal were used to spell the names of Hanrott’s children.48 Was our Book of Common Prayer created with a mentality closer to that captured by these examples or to that of the Little Gidding community? Without further evidence, it is impossible to say.

The ethical and historical complexities that accompany the cutting up of texts have been explored in another recent catalogue, from the Caxton Club’s 2005 exhibition on the so-called “leaf book”—a somewhat paradoxical tradition in the history of connoisseurship where deluxe studies of rare early printing were published in limited editions for collectors and accompanied by an original page (or leaf) cut from the book being venerated. As Christopher de Hamel explains, from one view this practice involved the destruction of one book “so that its pieces might be used to ornament or improve another book”—indeed, the destruction of the very book being commemorated by those other books.49 From another view, though, this is just a bibliographical variant of the age-old practice of “relic-collecting.”50 And while Paul Needham has rightly decried the breaking up and rebinding of early collections of Caxton imprints as a profound “failure of historical imagination,”51 it is entirely possible that our recycled medieval initials represent the product of a different kind of historical imagination, one with an equally profound desire to keep in touch with the past and a deep-seated investment in the religious power of illuminated letters.

If it is difficult to interpret the motivation behind the apparently violent act of cutting up books, it is also easy to overstate the spread and success of the image-purging program of the iconoclasts. While traditional images retained their place in the furniture and decoration of a surprising number of post-Reformation churches (as Eamon Duffy showed in his pioneering work The Stripping of the Altars), Protestant books also retained their dependence on traditional visual strategies. Ian Green explains that the 1569 and 1578 prayer books published by John and Richard Daye were “heavily decorated in a manner found in many earlier printed French primers, with selected scenes from Christ’s life and Old Testament prefigurations of the same, gesticulating prophets . . . and the medieval dance of death/ . . . all flanked by architectural, floral, and grotesque ornaments. The result, suggested Helen White, ‘must have looked to any informed reader like a resurrection of the old Primer.’ ”52 And he goes on to observe that “it is perhaps a relic of the primer’s hold that devotional works were much more likely to have a woodcut or engraving attached to them than any of the other genres. . . . There is a certain irony here, and presumably a selling point too, in that the primers in the hands of ordinary laymen before and immediately after the Reformation had been generally plain, but under Mary and again from the late 1560s readers of middling rank were quite likely to have a devotional manual with at least some illustrative stimuli.”53

These stimuli served several possible functions. Duffy has suggested that the “ornamentation that most primers contained would have established for their readers the fact that they were, in the first place, sacred objects . . . channels of sacred power independent of the texts they accompanied.”54 But they also served to structure the text—particularly before running titles and chapter headings became standard—helping the reader to find his way around and to find his way back to particular sections. It is instructive, once again, to read forward from the Middle Ages, where there was a long and lively tradition of intermingling words and images—in books of devotion but also other texts involving meditation and memory, from historical chronicles to legal decretals.55 And while the use of images for mnemonic and didactic purposes has generally been associated with unlettered readers still making the transition from orality to writing, these functions are still operative in the margins of books in contexts where textual and even typographical literacy were well advanced.

It is worth recalling, further, that the Protestant prayer book itself retained a number of features—both visual and verbal—from the traditional liturgy: for the more zealous reformers, indeed, it did not go far enough in removing the devotional residue from England’s Catholic past.56 In her important work on so-called church papists, Alexandra Walsham has reminded us that

This was a context in which meaningful religious distinctions were only gradually evolving, an age in which those deceptively neat denominational labels we are so tempted to employ were profoundly anachronistic. The term “church papist” was one symptom of this state of flux. Identifying a sector of the population that occupied a kind of confessional limbo, it was stretched to designate a bewildering variety of opinions and attitudes, a wide spectrum of positions and stances. . . . Clear-cut divisions between “Catholicism” and “Protestantism” did not pass into being in rural and urban localities as smoothly or rapidly as the legislation of [Elizabeth’s first] year: for several decades, continuity may have been more marked than change.57

And these continuities can even be found in the design of the new prayer book. It has not, I think, been observed that the use of decorative initials in the Protestants’ printed Book of Common Prayer is itself conspicuously “retro”: when Elizabeth issued a revised prayer book in 1561, the frequency and range of initials increased to the point where it rivals even the most fanciful pages of our manuscript.58 It is not surprising, then, that among the seven instructions given to the printer for the wholesale revision of the prayer book in 1661—telling him to “Set a faire Frontispiece at ye beginning of ye Booke,” to “Page the whole Booke,” and to “Adde nothing. Leave out nothing. Alter nothing, in what Volume soever it be printed. Particularly; never cut of[f] ye Lord’s prayer . . . with an [‘]&c[’] but . . . print them out at large”—was this telling item: “Print noe Capital Letters with profane pictures in them.”59

The retrofitting of the Elizabethan prayer book (and one final feature in our manuscript) is easiest to see not so much in the battle over contested sections of the liturgy but in the temporal frame that was put around them: the Book of Common Prayer, like the book of hours before it, prescribed a structure and sequence for readings from the Bible and Psalter and contained a calendar for special services and holidays for the entire year—both books made time itself holy.60 But if the traditional prayer book represented “Time Sanctified,” then the fate of the calendar in the Tudor prayer book is a story of time desanctified and partially resanctified. In the traditional Catholic primers leading up to the Reformation, almost every day in the calendar had a particular saint attached to it. These names became some of the earliest and most persistent targets of the Protestant Reformers, and they were steadily weeded out from the calendar: when the first Book of Common Prayer was published in 1549 they were almost completely purged from the calendar. Not surprisingly, they were fully restored in the Catholic primer issued by Queen Mary in 1555. The first Elizabethan prayer book of 1559 heralded a return to the virtually saint-less days of Edward VI, but over the next few years she moved steadily away from the “godly purity and simplicity” desired by the more zealous reformers. In 1560 she issued a Latin prayer book in which most of the saints were restored; this calendar is positively medieval and remains the most “sanctified” calendar ever to appear in an Anglican prayer book. Finally, in her English Book of Common Prayer of 1561, she settled on a compromise, with some saints finding their way back onto the calendar alongside the astrological information, dates of legal terms, and accession anniversaries of the English monarchs—and they stayed there for nearly a century. So while David Cressy is right that Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Elizabeth I gradually secularized and nationalized the calendar, replacing religious festivals with commemorations of historical events, and while Damian Nussbaum points out that Foxe put a provocative calendar in his Book of Martyrs with saints replaced by Protestant martyrs, many of Elizabeth’s subjects in 1561 would have felt she was reversing this process.61 But our manuscript of 1560–62 was produced by or for one of that other group of subjects, who were not ready to do away with the saints; and when it came time to copy the calendar, our scribe followed the recently revised calendar of 1561—though it is also worth noting that he did not add saints to the standard list, which some annotators did in their Books of Common Prayer, a practice that has allowed scholars of medieval books of hours to connect specific volumes with regions associated with particular saints.62

The Problem of Exceptional Evidence

This odd volume has forced us to survey a wide range of possible beliefs and behaviors and has ultimately presented us with an object that unsettles some of the easy oppositions that we often fall back on to make sense of this complex and even confused moment in the history of books, readers, and religion. It is a book that is itself stubbornly transitional, almost uncannily in-between: it takes us across the traditional divide between script and print but also into a number of other early Elizabethan middle grounds (to recall Hindman’s useful phrase)—between Catholic and Protestant, medieval and Renaissance, public and private, professional and amateur, production and consumption.

I have not found firm answers for many of the questions posed at the outset of this chapter; but, while there are few activities as satisfying to the scholar as solving mysteries, sometimes our historical investigations are more productive when we cannot pin things down. Our uncommon Book of Common Prayer presents itself as an exemplary instance of what Edoardo Grendi has called a “normal exception” (in an innovative program for combining microhistory and social history that has much to offer historians of reading).63 In their useful gloss on this concept, Carlo Ginzburg and Carlo Poni argue that “a truly exceptional . . . document can be much more revealing than a thousand stereotypical documents. As Kuhn has shown, it is the marginal cases that bring the old paradigm back into the arena of discussion, thus helping to create a new paradigm, richer and better articulated. These marginal cases function, that is, as clues to or traces of a hidden reality, which is not usually apparent in the documentation.”64 This, I would suggest, is this is the benefit—as well as the challenge—of working out from a single, seemingly peculiar text instead of starting with an argument and looking for examples that will illustrate it. Even when we cannot know how representative a single object or practice is, it can shed light on larger logics (structural, social, and symbolic) that only can be glimpsed in their particular manifestations.65