CHAPTER 15:

MAKING BEAUTIFUL BEER

A combine sets to work harvesting on Sierra Nevada’s 30-plus acres of barley at the brewery.

CHAPTER 15:

MAKING BEAUTIFUL BEER

A combine sets to work harvesting on Sierra Nevada’s 30-plus acres of barley at the brewery.

GOOD BEER IS EASY. GREAT BEER IS AN ENDLESS PURSUIT. CONVERTING SUGAR TO ALCOHOL IS SIMPLE ENOUGH, BUT TO EMULATE THE BEST BREWERIES, HOMEBREWERS NEED TO TAKE A CLOSER LOOK AT THEIR INGREDIENTS AND PROCESS.

Dumping caustic cleaner from the fermenter before pumping in wort at Epic Brewing Company

INTRODUCTION TO BETTER BEER

The quality of your beer is largely dependent upon two points. First there’s the character of your ingredients, which results from their variety and freshness. Then there’s how you control the brewing processes around your ingredients. Although homebrewers don’t have access to the same technology as professionals, many theories are easily adapted and the ingredients available are largely the same.

In this chapter you’ll learn about:

Selecting barley and hops

Cleaning and sanitation

Thermal stress

Oxidation

Trace metals in beer

BETTER INGREDIENTS, BETTER BEER

MALT

Barley and other brewing grains remain stable for both flavor and diastatic power if kept dry and uncrushed. To be safe, always taste your grains before buying or brewing to ensure there are no stale or off-flavors.

The greatest worry for homebrewers isn’t old grains, but old malt extract. Generally speaking, dried malt extract stays fresh up to a year, while liquid malt extract tends to deteriorate after six months. Old extract tends to darken in color and adds an unmistakable cider flavor to your beer.

HOPS

Hops help preserve beer, but they also lose their alpha acids quickly if they are not stored properly. In fact, hops begin to break down immediately after harvesting, giving wet-hopped ales an extra kick that is lost during drying and aging.

Hops distributors use humidity-controlled cold storage to minimize deterioration. If left at room temperature for six months, hops, depending on the variety, will lose anywhere between 20 and 65 percent of their alpha acids.

Immediately after harvest, hops are packaged with nitrogen to prevent oxidation. You can check hops for oxidation by smelling for cheesy aromas. Typically, you can use mildly oxidized hops for bittering as the off-flavors will boil away. If you don’t use all your hops and need to store them, pack them tightly in a plastic resealable bag and store them in your freezer. A vacuum sealer, however, is ideal. It’s worth noting that a small amount of oxidation does improve some hops. It can, for example, increase the floral quality in Cascade hops.

PELLET VS. WHOLE-FLOWER HOPS

There is a certain romance to using minimally processed whole-flower hops in your beer. Sierra Nevada has notably brewed with nothing but whole-flower hops for decades, but most of the great American IPAs are made with pellets and some even use hop oil extract, as we learned from Nick Floyd (see chapter 3). Still, there is no doubt that whole-flower hops make excellent beer. If you brew with whole-flower hops, be prepared for at least 10 percent lower alpha acid–utilization and a lot more vegetable matter to filter out of your kettle.

A homebrewer pours his yeast starter in after aerating the wort.

YEAST

The magical Saccharomyces cerversiae cells are resilient little buggers, but they have their limits. Dry yeast stays healthy in packets for about a year, while White Labs vials and Wyeast smack packs are fresh and fully viable for four months before beginning to lose a significant number of yeast cells. Using a yeast starter to set them up for a fast and healthy fermentation is one of the easiest steps to prevent infection as it outcompetes rival yeast and bacteria for sugar. See page 114 for yeast starter instructions.

CLEANING AND SANITATION

Don’t confuse the two as the same step; they have separate functions in giving you the best beer possible. Yes, good sanitary practices ensure no nasty creatures start growing in your beer, but cleanliness removes the grime and undesirable aromas from your equipment.

Cleaning is doubly important for plastic fermenters. While they are food grade, they’re easily scratched, giving bacteria a convenient place to hide from sanitizer and breed. Plastic buckets are also porous and can leach and carry over flavors from the previous batch. Dish soap is a simple cleaner, but it can leave a lingering aroma, and its residue will kill head retention. A dedicated brewing cleaner such as Five Star PBW (powdered brewery wash) is ideal and has a low environmental impact.

A longer, bigger boil isn’t always better. Brewing research shows that exposing the wort to excessive thermal stress can slightly degrade the flavor and stability of a beer. That means that it’s ideal to minimize your wort’s exposure to heat.

A sixty-minute boil is a good compromise that ensures DMS and other undesirable flavors are blown off, without subjecting the wort to undue stress. Also try to reduce the time it takes to heat and cool your wort. Think of your wort like any other food: The longer and hotter it’s cooked, the less flavor you have in the end.

OXIDATION AND AERATION

Oxygen provides vital fuel for yeast growth, but in all other instances, it’s a sworn enemy of beer. Before wort even hits the kettle, brewers work to reduce oxygen exposure in the grain mill and by removing dissolved oxygen from brewing water. This is called hot-side aeration, and in your brewhouse, boiling your water premash will drive off much of the oxygen while also removing chlorine. Also minimize splashing and aeration of your wort before the kettle.

On the cold side (postboil), any oxygen picked up after the initial fermentation can damage the beer and bring on a papery, cardboard character. Simple measures, such as not splashing your beer when transferring containers and, if possible, purging containers of oxygen with CO2, prevent introducing oxygen to the beer.

TRACE METALS

Brewing minerals and chemicals such as sulfate and chlorine get more attention in the brewing water, but copper and iron can also wreak havoc. Both bring a harsh metallic flavor, while copper slows mash enzymes, stunts yeast growth, and can cause gushing carbonation in a bottle or keg.

Thankfully, copper usually isn’t a threat to homebrewers unless they have bright unoxidized copper equipment. To be safe, avoid contact between your beer and copper at any stage after the boil. Iron is more prevalent and finds its way into your beer primarily through new stainless steel equipment or the use of diatomaceous earth water filters. Cleaning new stainless equipment will help remove that initial iron, and using a carbon filter, instead of diatomaceous earth, removes the risk of additional iron.

While a rolling boil removes DMS, backing off your heat can improve flavor.

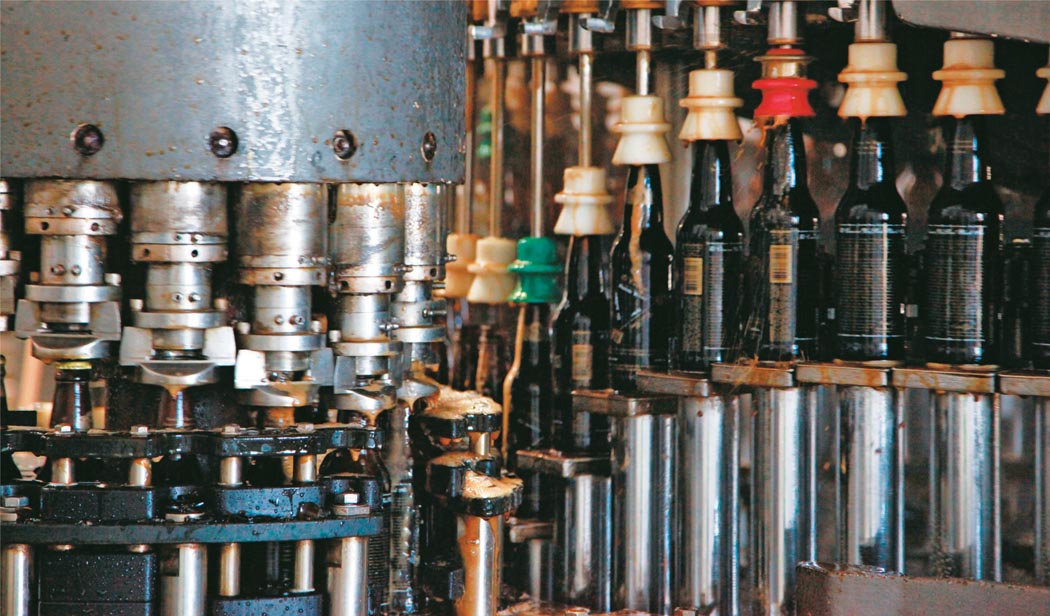

Bottling is an easy place for oxygen to sneak into beer for professionals and homebrewers alike.

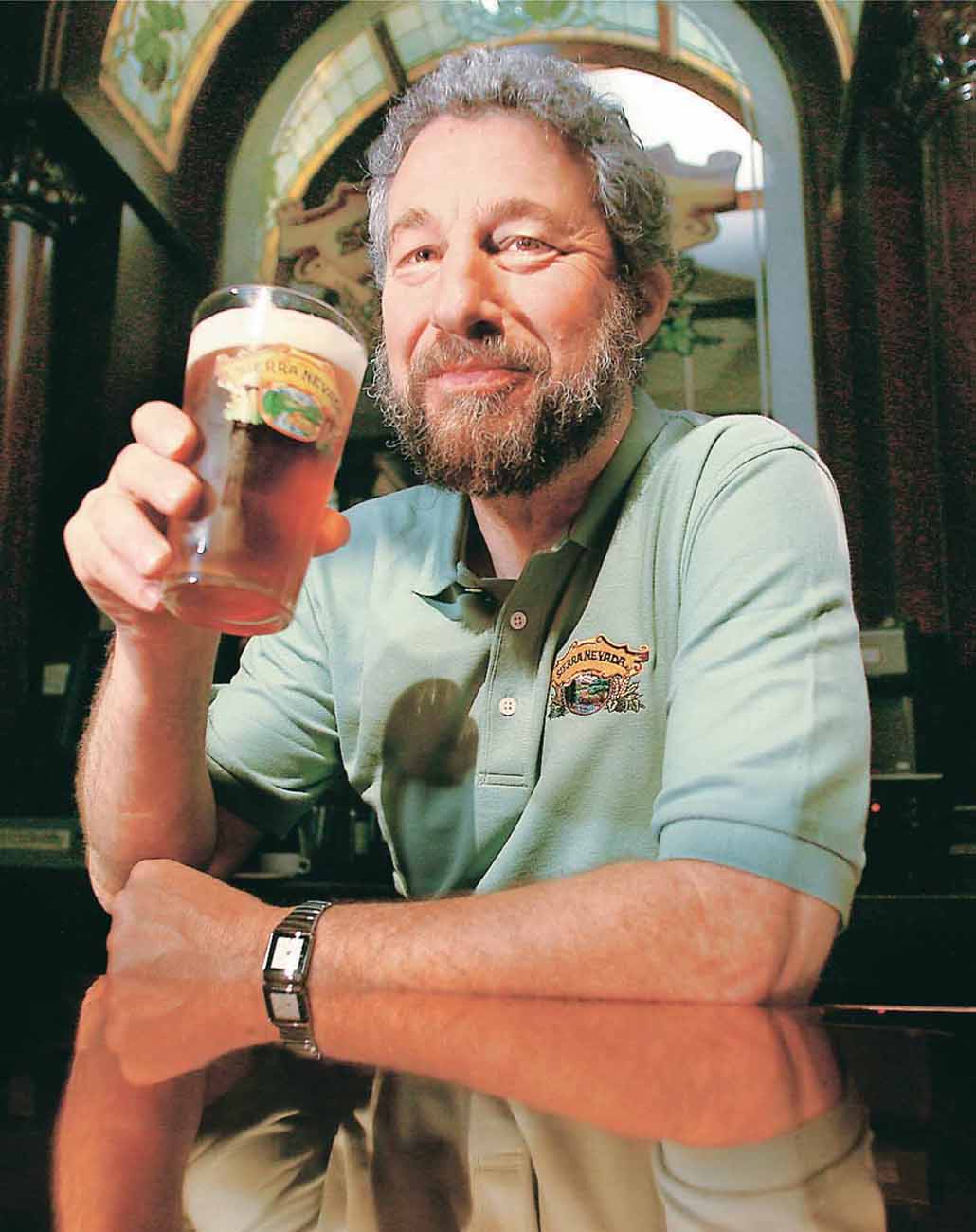

INTERVIEW WITH:

KEN GROSSMAN: OWNER, SIERRA NEVADA BREWING CO., CHICO, CALIFORNIA, U.S.

In 1979, Ken began by literally building his brewery by hand.

WITH A LEGENDARY CRAFT BEER TO HIS NAME, AN OWNER COULD BE COMPLACENT AND COAST, WATCHING THE PROFITS ROLL IN. BUT KEN IS A BEER GEEK FIRST AND FOREMOST. AFTER MORE THAN THREE DECADES IN THE BUSINESS, HE’S STILL RELENTLESSLY CHASING A BETTER BEER.

WHAT WERE THE BIGGEST CHALLENGES WHEN YOU FIRST OPENED IN 1980?

There wasn’t a place to buy brewing equipment on the budget or scale we had. I couldn’t have afforded something from Germany or England. But I was lucky that UC-Davis was down the road, and they had a pretty extensive brewing library. I went back into books from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, and saw how technology was handled in simpler times.

A lot of the articles I read and copied were on older methods of brewing. We tried to mimic simplified brewing systems with nonpressurized fermentation tanks or heated mash tuns that we now have the luxury of owning.

BUT HOW DID YOU HANDLE THE EQUIPMENT?

I built my first malt mill myself. We built a mash tun out of an old cheese vat I found, and I milled a false bottom myself. I used a lot of fundamental, but simplistic, equipment designs, but it was enough to get us into business.

BUILDING YOUR OWN MALT MILL SEEMS INCOMPREHENSIBLE.

I purchased well casing pipes, welded in end plates, put bearings together, and pieced together a functioning, but crude, malt mill that got us started. Those kind of skills were something I thought I needed, so I went back to junior college and took many classes in fabrication, machining, refrigeration, and so on.

It took a year and a half to put all the pieces together to make our first batch of beer, the building included. I did the carpentry, Sheetrock, painting, and all the plumbing and electrical.

I THINK SIERRA NEVADA HAS A REPUTATION FOR BEING THE BEST EXAMPLE OF THE ART AND TECHNICAL.

A lot of the small brewers that opened in the years before and after us are all gone. And part of their downfall was a lack of consistency, quality control, and getting a handle on brewing science. It’s certainly an art, but there’s science involved.

AND YOU’VE BEEN HEAD OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE FOR THE BREWERS ASSOCIATION.

It was great; my passion is the science of making beer. I’m boring and read brewing journals in the evening.

SO HOW DID THAT SCIENCE MANIFEST ITSELF?

We studied iron pickup in beer kegs and from water. A little bit of iron is not detectable by most palates, but 40 or 50 parts per billion of iron from natural sources or kegs severely impacts the flavor stability of beer. The consumer will experience a less-than-ideal beer down the road. It’s those subtle things that contribute to the overall long-term enjoyment of the product.

Today’s Sierra Nevada has an 800,000-barrel capacity.

WHAT SORT OF OTHER THINGS HAVE YOU FOUND IMPROVE FLAVOR STABILITY?

We blanket our mill with nitrogen, deaereate our brewing water, and we invest in analytical equipment that can look at ppb or lower of iron or other minerals. Not one of these things makes a huge impact by itself, but all these little bits can improve the consumers’ experience. That’s a core value: We always know we can do a little better here or there.

THAT MAKES ME THINK OF YOUR SWITCH TO PRY-OFF BOTTLE CAPS.

We’ve done a lot of research on bottle cap liner materials and are still working with European manufactures to find the Holy Grail of bottle cap liners. That’ll have benefits for us as well as the rest of the industry. Bottle caps are an inherent detractor from beer flavor stability.

We studied leaving twist-offs for many years. There was certainly the convenience factor, and hundreds of our customers voiced their discontent with our switching over. But we were not able to find a material that would work in a twist-off application as well as the best materials in a pry-off. The twist-off bottle caps have a mineral oil lubricant that allows the plastic to spin off, but it also lets more oxygen in.

WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE HOMEBREWERS ON HOW TO IMPROVE THEIR CONSISTENCY?

Adequate wort aeration is one thing too many homebrewers don’t get. Getting enough oxygen into the wort to get a quick fermentation and then getting active yeast in a state that it will start rapidly fermenting.

YOU GROW SOME OF YOUR OWN HOPS AND BARLEY. IT’S AN AWESOME WAY TO HELP PEOPLE UNDERSTAND THE CONNECTION BETWEEN SOIL AND WHAT WE ENJOY IN A PINT GLASS. DID ANYTHING DRIVE YOUR DECISION?

Actually, I have memories of moving to Chico in 1972. I was homebrewing and driving up through the Sacramento Valley when there were still hop fields along Highway 99. Then I made my first pilgrimage to Yakima in 1975. When I was starting my homebrew shop, I picked up a hundred brewers’ cuts to stock my homebrew shop with. Those are the 1-pound (455 g) bricks normally sent to brewers for selection.

In 2007, Sierra Nevada switched from twist-off to pry-off caps for better protection against oxygen.

I was always very into hops, so I thought it’d be great to show people what the raw materials look like. We got into it around 2004 and got a hop-picking machine from Germany. Then we started growing barley because we wanted to do an estate beer and had some open property. We have a little rail yard near the brewery to bring in malt [that has] 35 acres (0.1 km2) of agricultural land with water rights, so we thought it’s a perfect place to grow barley.

HOW DOES IT GROW?

Very well. We have great crops and do it all organically. One of our maltsters came here and said it’s the best organic field he’s ever seen. We’re still learning, trying to pump enough nitrogen into the soil organically. We have cover crops, fish emulsion, and whatnot. It’s challenging.

LET’S TALK ABOUT THE TECHNICAL SIDE OF SUSTAINABILITY.

Going back to innovating, we followed sustainable practices because we didn’t have any extra resources to waste. We started out with a bottle washer, and I used to go behind Mexican restaurants to dig out Dos Equis and Superior bottles because they were close enough to our bottle.

AND HOW’S THAT SPIRIT CARRIED ON TODAY?

Today, we’re a very public entity in our community. We acknowledge the fact that brewing is a resource-heavy industry for equipment, barley, transportation, use of water, and discharge of waste water. All those things are in my face, and we try to figure out how to be efficient without compromising quality.

Not all our products have great return on investment, but sometimes it’s the right thing to do and it helps with the company’s mind-set to occasionally acknowledge we’re doing something for the right reason, not because it’s going to save us money. We have a garden for the restaurant and just put in a composting system that can take up to 2.5 tons (2,270 kg) per day of food waste and produce compost in twelve to fourteen days.

SO YOU USE IT ALL?

We plan on it. We have a two-acre (8,100 m2) garden that we’re expanding plus a greenhouse. We want to raise the majority of our produce for the restaurant. After that, our hop and barley fields can take all of it.

Not all our products have great return on investment, but sometimes it’s the right thing to do and it helps With the company’s mindset to occasionally acknowledge we’re doing something for the right reason, not because it’s going to save us money. We have a garden for the restaurant and just put in a composting system that can take up to 2.5 tons per day of food waste and produce compost in twelve to fourteen days.

The brewery farms its own barley and hops on-site with hopes to eventually malt their own grains.