Figure 7.1 The music and health framework.

Physical, Mental, and Emotional

Suv i Saar ikallio

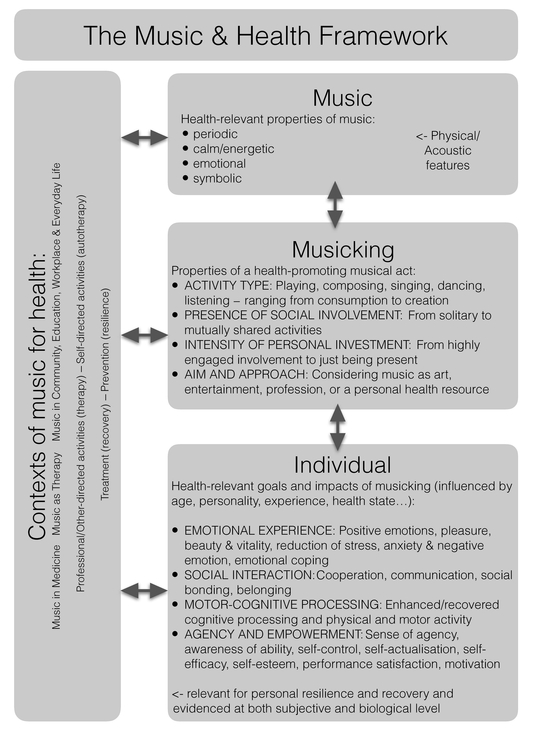

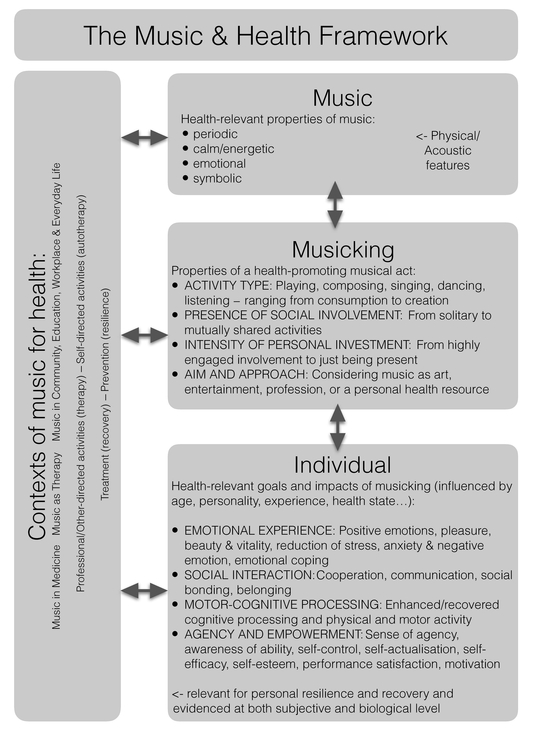

Music and health is one of the most rapidly growing research areas in music cognition. Scholars in psychology, neuroscience, psychoneuroendocrinology, and public health have taken a serious interest in investigating cultural activities such as music as a source of health, healing, and wellbeing. In 2012, the OUP volume Music, Health & Wellbeing (Eds. MacDonald, Kreutz, & Mitchell) brought together experts on music therapy, music medicine, public health, community music, and music education in a first step towards synthesizing our current understandings of how music connects to health and wellbeing. The realm of music and health is a vast one, touching on all aspects of human life. Therefore, this chapter begins with a presentation of a framework that provides an overall picture of the main factors involved (Figure 7.1). In this framework health and healing are conceptualized as covering the entire continuum from recovery and treatment to health promotion and health-beneficial growth. As illustrated in the figure, the framework further emphasizes the fact that musical healing always occurs in a certain context and is essentially a music-related act, performed and impacted by the individuals who engage with the music.

The major contextual dimension in musical healing differentiates the professional/clinical use of music in therapy and medicine from the potentially self-therapeutic engagement with music in everyday life. This dimension particularly involves differences in how consciously the health-relevant goals of the musical activity are laid down, and whether these goals are set solely by the individual him/herself or together with health professionals such as therapists, physicians, or social workers. In between clinical care and daily music listening, there also exists a variety of contexts, such as community music therapy and community work, use of music at work places, and music in educational settings (MacDonald, Kreutz, & Mitchell, 2012). Another major, and closely related, contextual dimension concerns treatment versus prevention, distinguishing between situations where music is particularly used for recovery and rehabilitation, and situations where music acts to promote resilience, mental wellbeing, personal resources, and adaptive development. The way in which a musical act relates

Figure 7.1 The music and health framework.

to these dimensions determines some of the characteristics and health-goals of the activity. However, despite varying on these major premises, the contexts of musical healing often appear to be characterized by highly similar health-impacts. For instance, stress reduction and the induction of positive moods has been systematically observed as a result of both music-based treatment interventions (Clark & Harding, 2012; Erkkilä et al. 2011; Field, Martinez, Nawrocki, et al. 1998; Maratos, Gold, Wang, & Crawford 2008; Menon & Levitin, 2005; Pelletier, 2004), and self-directed daily music engagement (Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007; Chin & Rickard, 2013; Van den Tol & Edwards, 2015). Some underlying similarities across contexts can therefore be assumed.

In explaining the linkage of music to health, the elaboration of the specific musical characteristics involved is of particular importance for understanding the special nature of music as a health resource, compared to other resources. Music as a physical and auditory phenomenon contains acoustic and perceptual properties, related to features like time, sound quality, and loudness, which form the basis of its health-relevant affordances. For instance, the rhythmic framework of musical expression enables entrainment and mutual synchronization between music and the individual, and between individuals, activating body movement and providing opportunities for social and cooperative acts and rewards (e.g. Thaut, 2005). The varying levels and degrees of qualities like tempo and sound volume impact the perception of music as calm or energetic, offering possibilities for influencing the energy levels of individuals. Consistent links have been demonstrated between a variety of acoustic features and the perception of music as expressive of a range of basic emotions (Gabrielsson & Lindström, 2001; Juslin & Laukka, 2003, 2004; Juslin & Timmers, 2010), providing resources for the emotional uses of music. Finally, the nature of music as a symbolic expression of various mental processes (Langer, 1942) and social identities (Frith, 2004) allows highly personalized and customized usage of music in music therapy. Such therapy may focus on personal identity, with both internal contemplation and interpersonal expression as therapeutic components (to read more about music as a symbolic process in a therapy context, see Fachner, this volume).

Despite the fact that music contains highly relevant characteristics for impacting human health, music itself is not considered in the present framework as the reason, but rather as the forum for healing. That is, health-related musical engagement is conceptualized first and foremost as an activity of an individual, in line with the ideas that underlie the notion of “musicking” (Small, 1998), which presents music as a process rather than an object. While the activities of singing, playing, composing, improvising, or dancing can easily be seen as acts, the consumption of music through listening can also fundamentally be considered as an engaged act, into which the listener brings his or her personal goals and attitudes.

The act of musicking can thus consist of a wide continuum of behaviors that range from the consumption of to the creation of musical material. Furthermore, these activities can be characterized by a variety of properties that play a role regarding the act’s health-impact. For instance, the activity can range from a solitary engagement to an intrinsically social act, whether it be group drumming, participation in a concert with a thousand fans, listening to a favorite song with a group of friends, performing to strangers, improvising with a therapist, singing in a choir, or dancing intimately with a partner (cf. Lamont, this volume).

Another relevant element is the intensity of personal involvement. Sometimes musicking means merely to be present in a situation where there is music, without much personal interest or even attention. Sometimes, in contrast, the involvement is passionate, personal, and intensive, whether it is because of the love for the type of music being listened to, because of the social character of the situation, or because of a process of externalizing some deeply personal content to a musical form. Studies have shown that in the context of daily music listening clear differences exist between highly engaged and non-engaged listeners and that the amount of engagement is linked with the amount of personal and purposeful mood and activity supporting uses of music (Greasley & Lamont, 2011). The intensity of personal investment also involves issues of focused attention and flow, states that are linked with high personal satisfaction and subjective wellbeing (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990, 2014). Finally, the act of musicking is fundamentally grounded in the personal attitude and understanding of the very meaning of the act, ranging from considering the act as an art experience to daily entertainment and from a professional act to using music as a personal health-resource, such as listening to “my comfort music.” With these considerations expressed, it is clear that the act of musicking consists of an immensely complex entity of factors that are likely to be influential upon the observed healing-effects of music and that the current research has only grasped the surface of their interactive influences.

In this section of the chapter we discuss the individual level of musical healing, focusing on the different elements that broadly constitute healing within an individual. This again is a broad topic, since health itself is a vast area of interrelated elements that range from motor behavior to socio-emotional behavior and from understanding disorders and their treatments to the nature and encouragement of human flourishing. The first element to be discussed is emotion, which possibly is the most evident aspect of the health-relevance of music, and, as stated before, is widely evidenced in both clinical and everyday life contexts. The impact of music on emotion appears central for why music is relevant for both physical and mental health (MacDonald, Kreutz, & Mitchell, 2012), observed across cultures (Saarikallio, 2012), and involving processes that range from an increased awareness of emotion to the ability of managing them: inducing pleasurable emotions and adaptively regulating the avoidable ones (Saarikallio, 2016). The efficacy of music in evoking positive emotions has been indexed by self-reports (Juslin & Laukka, 2004; Scherer & Zentner, 2008); brain activation in areas connected to motivation, pleasure, and reward, including the ventral striatum, dorsomedial midbrain, amygdala, hippocampus, insula, cingulate cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex (cf. Granot, this volume; see also Blood & Zatorre, 2001; Koelsch, 2014; Menon & Levitin, 2005); shifts of frontal brain activity towards the left hemisphere (Field, Martinez, Nawrocki, et. al, 1998; Schmidt & Trainor 2001); and a variety of other physiological indicators of positive affect involving heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, skin conductivity, and biochemical responses (Bartlett, 1996).

In addition to such physiological markers, more centrally mental and emotional effects have been documented. Interventions with depressed individuals serve as a particularly illustrative example of the positive impact of music on mood (Erkkilä, Punkanen, Fachner, & Gold 2011; Field, Martinez, Nawrocki, et al. 1998; Maratos, Gold, Wang, & Crawford 2008). The impacts of music on reducing stress and anxiety have widely been evidenced through research on the endocrine system. These effects particularly involve the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis (HPA), a central hormone of which is cortisol, and decreases of cortisol levels have been systematically observed in relation to music listening tasks, singing, playing, and music therapy interventions (for a review, see Koelsch & Stegemann, 2012; Kreutz, Quiroga Murcia, & Bongard, 2012). Other systematically observed hormonal changes indicative of the reduced stress levels in relation to music engagement include increases of oxytocin and β-endorphin (Kreutz et al., 2012).

Finally, the efficiency of music in pain management has been shown in a variety of experimental studies (Mitchell & MacDonald, 2012) and music has been efficiently used to alleviate preoperative anxiety and stress, and to function as a non-pharmacological pain management tool in medical operations and surgery (Bernatzky, Strickner, Presch, Wendtner, & Kullich, 2012; Spintge, 2012). Considering the strong and widely evidenced impact of music on emotion (Timmers, this volume), it is no surprise that experiences related to the induction and regulation of emotional valence and arousal are a major reason for engaging in music in daily life (Juslin & Laukka, 2004), a major component of why music is rewarding (Mas-Herrero, Marco-Pallares, Lorenso-Seva, Zatorre, & Rodriguez-Fornells, 2013), and a characterizing element of musical coping and mental health maintenance (Miranda, Gaudrea, Debrosse et al., 2012).

Another major area of the health-relevance of music involves social interaction. The evolutionary significance of music is likely to be grounded in the ability of music to strengthen social bonding and cooperation (Clayton, 2009; Cross, 2014, 2016; Mithen, 2005). Many philosophical approaches to music embrace it fundamentally as a socially embedded and interactive act (Elliott, & Silverman, 2012) and the social dimension of music is considered as a core feature of its health-impact regardless of cultural context (Saarikallio, 2012). The use of musical elements for socio-emotional bonding and communication emerges early in mother-infant interaction, being an important part of learning emotional communication and forming a secure attachment (Malloch, 1999; Trevarthen, 1999, 2002; Trehub, Unyk, & Trainor, 1993; Oldfield, 1993; Trainor & Cirelli, 2015).

Later in development, engagement in joint musical activity encourages prosocial cooperative behavior in 4 year-olds (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2012). Studies on group singing and dancing also indicate clear connections of musical activity to increased experiences of social communication and bonding (Davidson & Emberly, 2012; Clift, 2012; Quiroga Murcia & Kreutz, 2012). As a medium for communication, music functions at a deep level of affective, amodal, and symbolic expression (Stern, 2010) and can therefore serve the human interaction even when language fails, such as with autistic patients (Ockelford, 2012). While the social affordances of music are highly relevant for all musical contexts from education to group therapy, they are perhaps most pronounced and elaborated in the context of community music therapy, a rapidly growing field of practice and research, which is grounded on the idea of using music for empowering people through increased social participation, identification, and interaction with their community (Ansdell & DeNora, 2012; Murray & Lamont, 2012; Ruud, 2012).

The multifaceted nature of music as a social resource is illustrated with a list of “seven Cs” by Koelsch and Stegemann (2012): making contact with others, understanding others through social cognition, feeling co-pathy for the feelings of others, communicating emotional information, coordinating action through synchronized movement, cooperating for a shared musical goal, and feeling social cohesion and belonging to others. Koelsch and Stegemann particularly discuss the physiological correlates of these experiences at the levels of neural, hormonal, and immune system activity, showing how the impact of music has been widely evidenced also through physiological reactions, not only the ones linked with increased positive affect and stress reduction as discussed above but also the ones more directly linked with social bonding, such as release of oxytocin.

The impact of music on cognitive and motor behavior forms yet another major healing-relevant area. Music training and music listening have been systematically connected with improved cognitive functioning involving, for instance, spatial-temporal processing and concentration (Schellenberg, 2012; Costa-Giomi, 2012). In particular, the long-term dedicated commitment to learning a musical instrument appears to have positive impacts on children’s cognitive development (Costa-Giomi, 2012).

The ability of music to activate motor-cognitive processing can be used for healing purposes in a variety of different contexts that range from a systematic use of music in therapy and rehabilitation with cognitively impaired individuals (e.g. Ockelford & Markou, 2012) to community activities with elderly people who naturally face reduction of motor-cognitive functioning (Gembris, 2012). Recent studies show promising results in all of these areas: music therapy work with cognitively impaired children (e.g. Ockelford & Markou, 2012), hospital settings where music listening is enhancing cognitive recovery after stroke (Särkämö et al., 2008), and everyday musical hobbies functioning as a protection against dementia in old age (Gembris, 2012). To read more about the clinical/therapeutic use of music for improving motor-cognitive behavior see Fachner (this volume) and Henry and Grahn (this volume). Different musical activities also appear to rely on different underlying impact mechanisms. With regards to music listening, the most plausible mechanism explaining improved cognitive processing appears to be the mood and arousal hypothesis: Cognitive performance becomes improved because music helps to achieve an optimal arousal and mood state (Schellenberg, 2012). Meanwhile, the various forms of music making and musical learning involve a wide combination of mechanisms with differing impacts from the rudimental training of motor-cognitive skills to the more executive level of learning concentrated goal-orientation for achievement. For example, the activity of dancing— fundamentally bodily movement—has been linked with fitness indicators such as aerobic capacity, balance, coordination, elasticity, muscle strength, kinesthetic awareness, and body control (Quiroga Murcia & Kreutz, 2012). Engagement in musical hobbies in general provides a forum for learning to merge pleasure with goal-oriented hard work through the experiences of deep concentration and flow (Csíkszentmihályi & Larson, 1984). Overall, the impact of music on improved cognitive and motor behavior is also strongly linked with the socio-emotional aspects that make music engagement a particularly motivating and enjoyable form of motor-cognitive training.

The final, more meta-level element of musical healing could be labeled as agency and empowerment, an element that partly arises as a constitution of the abovementioned elements. “Sense of agency” is a concept that refers to the subjective awareness of being the person who is initiating, executing, and controlling one’s own actions, bodily movement, and thoughts—taking ownership of one’s behavior (Jeannerod, 2003). The sense of agency relates to experiencing oneself as an independent self, and is reflected in the brain by activation of particular cortical networks, impairments of which relate to pathological conditions such as schizophrenia (Farrer, et. al., 2004). It is closely linked to concepts such as internal locus of control (Rotter, 1966) and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), which both are highly relevant for health and wellbeing (Roddenberry & Renk, 2010) and further link to experiences of self-esteem (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, 2002). Ruud (1997) connects the sense of agency to health resources as defined by Aaron Antonovsky: Feeling that life is comprehensible (predictable), manageable (conceivable), and meaningful. Ruud shows that music can serve as a fundamental daily resource for such experiences by achieving a greater awareness of one’s own possibilities of action and providing feelings of mastery, achievement, and empowerment.

The ability of music to promote self-agency is a core element in understanding how music supports adolescents’ healthy psychosocial development (Laiho, 2004; Gold, Saarikallio & McFerran, 2011) and the increased experience of personal empowerment is a fundamental reason for why music is important for persons with long-term illnesses (Batt-Rawden, et al., 2005). The empowering capacity of music ranges from the mundane situations of providing personalization to daily activities through music listening choices (Sloboda & O’Neill, 2001) to music-induced feelings of self-control serving as the mediator for the ability to manage pain. Recent findings show that the feeling of empowerment is a core constituent of why music is considered pleasurable in daily life (Maksimainen & Saarikallio, 2015). The health-relevance of personal agency in music engagement is also illustrated by situations where agency is lacking: Adolescents who were receiving support for depression, anxiety, or emotional and behavioral problems appeared relatively unable, in comparison to their healthy peers, to identify, take responsibility for, and change their maladaptive patterns of music use towards more healthy patterns (McFerran & Saarikallio, 2013). Overall, the ability of music to empower individuals is an understudied and vaguely conceptualized topic, compared to emotion, social interaction, and motor-cognitive behavior, but should definitely be considered as a fundamental part of understanding how music functions to promote health and in developing resilience and wellbeing.

In the framework presented above, healing is not purely seen as a result of music engagement by a person, but rather as an act that is fundamentally initiated and directed by that very person. The impacts of musical healing are therefore seen as closely intertwined with personal goals and reasons for musical engagement, and are fundamentally rooted in individual factors such as personality, age, and mental health state. This line of thinking is strongly supported by the distinct individual differences observed in musical engagement, even with the very same musical material. Certain types of individuals appear to be more likely to gain certain types of benefits from music: Music listening, for instance, effectively reduces stress levels, particularly in non-musicians (VanderArk & Eli, 1993), adolescents, and females (Pelletier, 2004).

These differences in impact are partly based on the varied ways in which people approach and experience music. Personality traits impact musical experience at the level of perceiving music in a certain way: Extraversion, openness, and agreeableness correlate with a bias for perceiving higher amounts of positive and lower amounts of negative emotions in music, while neuroticism relates to an opposite pattern (Vuoskoski & Eerola, 2011; for more about personality traits and music, see Vuoskoski, this volume).

Mental health states also bias music perception: Clinical depression (Punkanen, Eerola, & Erkkilä, 2011) and negative mood (Vuoskoski & Eerola, 2011a) correlate with a bias for higher ratings for perceived negative and lower ratings for perceived positive emotion in music. These trait and state congruent biases and other individual differences thus already exist at the fundamental level of perception and approach towards music, and they further impact the ways in which music may be used as a health resource. For instance, the emotional use of music for mood regulation is more typical for females than males (e.g., Wells & Hakanen, 1991; Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2009b), for people who engage with music informally, not formally (Saarikallio, Nieminen, & Brattico, 2013), and for individuals high in neuroticism (Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2009a, 2009b). Furthermore, from the healing perspective it is essential also to take a deeper look at the characteristics of musical engagement. That is, in emotion regulation, it is not the amount of regulation per se that makes a difference, but rather that the engagement patterns can be considered health-beneficial or even harmful. Indeed, depressed individuals have been shown to engage in patterns of emotional music use that can be considered maladaptive, such as rumination and avoidance (Garrido, Schubert, & Bangert, 2016; McFerran & Saarikallio, 2013; Miranda & Claes, 2009; Saarikallio, Gold, & McFerran, 2015). Similarly, anxiety and neuroticism relate to another undesirable strategy, using music for venting negative emotion (Carlson et al., 2015). Meanwhile, the ability to shift attention from negative thoughts and emotions towards positive ones through aesthetic pleasure (Van Den Tol & Edwards, 2015), dancing (Chin & Rickard, 2013), or regulatory strategies of positive reappraisal and distraction (Chin & Rickard, 2013; Van Den Tol, & Edwards, 2015) relates to positive health outcomes.

Differential impact of these music engagement patterns on emotional processing has also recently been evidenced at the level of brain activation: Males who typically use music for venting and discharging negative emotion show lower activation in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) as a response to emotion-evoking music, while females who typically engage in music for diverting away from negative thoughts show an increase in the mPFC activation, as a response to the same music (Carlson, et al., 2015). Striking differences exist in an individual’s ability to become aware and take agency in actively modifying personal music engagement towards health-beneficial outcomes: Healthy adolescents efficiently use various techniques—even sad music listening and negative emotion processing—as steps towards mood improvement and healing (Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007), while vulnerable and depressed adolescents allow music to reinforce and fuel their negative emotions, ruminative tendencies, and feelings of social isolation (McFerran & Saarikallio, 2013).

The above-mentioned examples concern the emotional use of music, but the same principle applies to the other elements of healing: Individuals are likely to differ in their ability to use music to foster social interaction, motivate motor-cognitive behavior, and encourage personal empowerment. Research on music and health should be able to identify the personal capacity of different individuals for the health-beneficial use of music and possibilities for building such capacity could then subsequently be targeted at interventions, involving not only music therapeutic practice and recovery, but also preventive endeavors for promoting wellbeing, resilience, and personal growth. The Healthy-Unhealthy-Music Scale (HUMS) is a pioneering instrument for such purposes, specifically designed for identifying music use that is reflective of a risk for adolescent depression and to be used as a guide for preventive work with such individuals (Saarikallio, Gold, & McFerran, 2015).

The music and health framework presented in this chapter provides an overall map for comprehending the different elements that play a role in understanding musical health and healing. New research is rapidly emerging about the impacts of various forms of musicking on the different psychological, physiological, and social aspects of health and wellbeing. The role of individual factors in understanding these impacts is also receiving increased attention and, in the same way that the daily music use has become an individualized act, so should interventions be customized to foster individualized needs of particular target groups. Awareness of the interactive nature of the various individual, contextual, and musical elements is a fundamental starting point for situating particular healing interventions and experimental studies in their broader context, and for considering possible confounding and mediating factors. A more comprehensive understanding of this broader picture helps both researchers and practitioners to make grounded decisions about choosing particular elements as the focus of single studies or interventions: The context of the healing activity (e.g. prevention or rehabilitation), as well as the targeted element of psychopathology (e.g. stress or depression), particularly motor-cognitive challenge (e.g. memory loss or speech problem), or a social-emotional goal (e.g. fostering pro-social development), as well as a range of other individual factors (e.g. gender, mental health state) play a role in determining optimal requirements for the musical material and the musicking activity. They should also be carefully considered when choosing which self-reported, observed, and physiological outcome measures should be used for assessing whether desired health-outcomes have been reached. Research in this field is growing quickly, and the future is likely to provide better identification of various optimal and customized combinations regarding the different elements that best foster musical healing at the levels of individual and social recovery and growth.

Koelsch, S., & Stegemann, T. (2012). The brain and positive biological effects in healthy and clinical populations. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 436–456). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kreutz, G., Quiroga Murcia, C., & Bongard, S. (2012). Psychoneuroendocrine research on music and health: An overview. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 457–476). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Menon, V., & Levitin, D. (2005). The rewards of music listening: Response and physiological connectivity of mesolimbic system. Neuroimage, 28, 175–184.

Saarikallio. S. (2012). Cross-cultural approaches to music and health. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 477–490). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saarikallio, S., & Erkkilä, J. (2007). The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 88–109.

Ansdell, G., & DeNora, T. (2012). Musical flourishing: Community music therapy, controversy, and the cultivation of wellbeing. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 97–112). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bartlett, D. L. (1996). Physiological responses to music and sound stimuli. In D. A. Dodges (Ed.), Handbook of music psychology (pp. 343–385). 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: IMR.

Batt-Rawden, K. B., DeNora, T., & Ruud, E. (2005). Music listening and empowerment in health promotion: A study of the role and significance of music in everyday life of the long-term ill. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 14(2), 120–136.

Bernatzky, G., Strickner, S., Presch, M., Wendtner, F., & Kullich, W. (2012). Music as nonpharmacological pain management in clinics. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 257–275). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blood, A. J., & Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(20), 11818–11823.

Carlson, E., Saarikallio, S., Toiviainen, P., Bogert, B. Kliuchko, M., & Brattico, E. (2015). Maladaptive and adaptive emotion regulation through music: A behavioral and neuroimaging study of males and females. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 466. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00466

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Gomi-Freixanet, M., Furnham, A., & Muro, A. (2009a). Personality, self-estimated intelligence, and uses of music: A Spanish replication and extension using structural equation modeling. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3(3), 149–155.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Swami, V., Furnham, A., & Maakip, I. (2009b). The big five personality traits and uses of music. A replication in Malaysia using structural equation modeling. Journal of Individual Differences, 30(1), 20–27.

Chin, T., & Rickard, N. S. (2013). Emotion regulation strategy mediates both positive and negative relationships between music uses and well-being. Psychology of Music, 42(5), 92–713.

Clark, I., & Harding, K. (2012). Psychosocial outcomes of active singing interventions for therapeutic purposes: A systematic review of the literature. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 21(1), 80–98.

Clayton, Martin (2009). The social and personal functions of music in cross-cultural perspective. In Hallam, S., Cross, I., & Thaut, M. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music psychology (pp. 35–44). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clift, S. (2012). Singing, wellbeing & health. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 113–124). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Costa-Giomi, E. (2012). Music instruction and children’s intellectual development: The educational context of music participation. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 339–355). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cross, I. (2014). Music and communication in music psychology. Psychology of Music, 42(6), 808–819.

Cross, I. (2016). The nature of music and its evolution. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, and M. Thaut (Eds.) Oxford handbook of music psychology (pp. 3–18). 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1984). Being adolescent: Conflict and growth in the teenage years. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Davidson, J., & Emberly, A. (2012). Embodied musical communication across cultures: Singing and dancing for quality of life and wellbeing benefit. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 136–149). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, D. J., & Silverman, M. (2012). Why music matters: Philosophical and cultural foundations. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 25–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M.,. . . Gold, C. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: Randomized controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(2), 132– 139.

Farrer, C., Franck, N., Frith, C. D., Decety, J., Damato, T., & Jeannerod, M. (2004). Neural correlates of action attribution in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 131, 31–44.

Field, T., Martinez, A., Nawrocki, T., et al. (1998). Music shifts frontal EEG in depressed adolescents. Adolescence, 33, 109–116.

Frith, S. (2004). Popular music: Critical concepts in media and cultural studies. Volume 4 Music and identity. London: Routledge.

Gabrielsson, A., & Lindström, E. (2001). The influence of musical structure on emotional expression. In P. N. Juslin, & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Music and emotion: Theory and research (pp. 223–248). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Garrido, S., Schubert, E., & Bangert, D. (2016). Musical prescriptions for mood improvement: An experimental study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 51, 46–53.

Gembris, H. (2012). Music-making as a lifelong development and resource for health. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 367–382). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gold, C., Saarikallio, S. H., & McFerran, K. (2011). Music therapy. In R.J. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1826–1834). New York, NY: Springer.

Greasley, A. E., & Lamont, A. (2011). Exploring engagement with music in everyday life using experience sampling methodology. Musicae Scientiae, 15(1), 45–71.

Jeannerod, M. (2003). The mechanism of self-recognition in human. Behavioral Brain Research, 142, 1–15.

Judge, T. A, Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 693–710.

Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2003). Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychological Bulletin, 129, 770–814.

J uslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2004). Expression, perception, and induction of musical emotions: A review and a questionnaire study of everyday listening. Journal of New Music Research, 33(3), 217–238 .

Juslin, P. N., & Timmers, R. (2010). Expression and communication of emotion in music. In P. N. Juslin & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 453–92). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kirschner, S., & Tomasello, M. (2012). Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 354–364.

Koelsch, S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 170–180 doi:10.1038/nrn3666

Laiho, S. (2004). The psychological functions of music in adolescence. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 13(1), 49–65.

Langer, S. (1942). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

MacDonald, R., Kreutz, G., & Mitchell, L. (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Malloch, S. N. (1999). Mothers and infants and communicative musicality. Musicae Scientiae, 3(1), 29–57.

Maksimainen, J., & Saarikallio, S. (2015). Affect from art: Subjective constituents of everyday pleasure of music and pictures: Overview and early results. Paper presented at the Ninth Triennial Connference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, Manchester, UK.

Maratos, A., Gold, C., Wang, X., & Crawford, M. (2008). Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 2008(1), CD004517.

Mas-Herrero, E., Marco-Pallares, J., Lorenso-Seva, U., Zatorre, R., & Rodriguez-Fornells, A. (2013). Individual differences in music reward experiences. Music Perception, 31(2), 118–138.

McFerran, K., & Saarikallio, S. (2013). Depending on music to feel better: Being conscious of responsibility when appropriating the power of music, The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(1), 89–97.

Miranda, D., & Claes, M. (2009). Music listening, coping, peer affiliation and depression in adolescence. Psychology of Music, 37, 215–233.

Miranda, D., Gaudrea, P., Debrosse, R., Morizot, J. & Kirmayer., L. (2012). Music listening and mental health: Variations on internalizing psychopathology. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 513–529). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mithen, S. (2005). The singing Neanderthals. The origins of music, language, and body. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Murray, M., & Lamont, A. (2012). Community music and social/health psychology: Linking theoretical and practical concerns. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 76–86). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ockelford, A. (2012). Songs without words: Exploring how music can serve as a proxy language in social interaction with autistic children. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 289–323). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ockelford, A., & Markou, K. (2012). Music education and therapy for children and young people with cognitive impairments: Reporting on a decade of research. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 383–402). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oldfield, A. (1993). Interactive music therapy in child and family psychiatry. Clinical practice, research, and teaching. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Pelletier, C. L. (2004). The effect of music on decreasing arousal due to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 16(3), 192–214.

Punkanen, M., Eerola, T., & Erkkilä, J. (2011). Biased emotional recognition in depression: Perception of emotions in music by depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 13(1), 118–126.

Quiroga Murcia, C., & Kreutz, G. (2012). Dance and health: Exploring interactions and implications. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 125–135). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roddenberry, A., & Renk, K. (2010). Locus of control and self-efficacy: Potential mediators of stress, illness, and utilization of health services in college students. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41(4), 353–370.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General & Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Ruud, E. (1997). Music and the quality of life. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 6(2), 86–97.

Ruud, E. (2012). The new health musicians. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 87–96). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saarikallio, S. (2016). Musical identity in fostering emotional health. In. R. MacDonald, D. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds). Handbook of musical identities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saarikallio, S., Gold, C., & McFerran, K. (2015). Development and validation of the Healthy-Unhealthy Music Scale (HUMS). Development and validation of the Healthy-Unhealthy Music Scale. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(4), 210–217. doi:10.1111/camh.12109

Saarikallio, S., Nieminen, S., & Brattico, E. (2013). Affective reactions to musical stimuli reflect emotional use of music in everyday life. Musicae Scientiae, 17(1), 27–39.

Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M., Laitinen, S., Forsblom, A., Soinila, S., Mikkonen, M., . . . & Peretz, I. (2008). Music listening enhances cognitive recovery and mood after middle cerebral artery stroke. Brain, 131(3), 866–876.

Schellenberg, E. G. (2012). Cognitive performance after listening to music: A review of the Mozart Effect. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 324–338). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scherer, K., & Zentner, M. (2008). Music evoked emotions are different – more often aesthetic than utilitarian. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31(5), 595–596.

Schmidt, L. A., & Trainor, L. J. (2001). Frontal brain electrical activity (EEG) distinguishes valence and intensity of musical emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 15(4), 487–500.

Sloboda, J. A., & O’Neill, S. A. (2001). Emotions in everyday listening to music. In Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (Eds.), Music and emotion: Theory and research (pp. 415–429). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Hano ver, NH: University Press of New England.

Spintge, R. (2012). Clinical use of music in operating theatres. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing (pp. 276–286). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, D. (2010). Forms of vitality. Exploring dynamic experience in psychology, the arts, psychotherapy, and development. London: Oxford University Press.

Thaut, M. H. (2005). Rhythm, human temporality and brain function. In D. Miell, R. MacDonald, & D. J. Hargreaves (Eds). Musical communication (pp. 171–192). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Trainor, L. J., & Cirelli, L. (2015). Rhythm and interpersonal synchrony in early social development: Interpersonal synchrony and social development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, March 2015.

Trehub, S. E., Unyk, A. M., & Trainor, L. J. (1993). Maternal singing in cross-cultural perspective. Infant Behavior and Development, 16(3), 285–295.

Trevarthen, C. (1999). Musicality and the intrinsic motive pulse: Evidence from human psychobiology and infant communication. Musicae Scientiae, 3(1 suppl), 157–213.

Trevarthen, C. (2002). Origins of musical identity: Evidence from infancy for musical social awareness. In R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds.), Musical identities (pp. 21–38). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van den Tol, A. J., & Edwards, J. (2015). Listening to sad music in adverse situations: How music selection strategies relate to self-regulatory goals, listening effects, and mood enhancement. Psychology of Music, 43(4), 473–494.

VanderArk, S. D., & Ely, D. (1993). Cortisol, biochemical, and galvanic skin responses to music stimuli of different preference values by college students in biology and music. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 77(1), 227–234.

Vuoskoski, J. K., & Eerola, T. (2011). Measuring music-induced emotion. A comparison of emotion models, personality biases, and intensity of experiences. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2), 159–173.

Wells, A., & Hakanen, E. A. (1991). The emotional use of popular music by adolescents. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 68(3), 445–454.