BEER FLAVOR IN YOUR BREWERY

RON SIEBEL

Updated 1993 by Ilse Shelton, Siebel Institute of Technology

The topic of this chapter is beer flavor, and specifically, how it is measured. I’d like to first address the need for tasting, and then some preliminaries for setting up a beer-flavor profile. This information is a very good tool in controlling beer flavor.

I’ll spend the bulk of my time looking at a method of flavor profiling that was introduced to the industry in the 1960s. It was the first working profile in use in this country, and is still being used by a number of breweries. We at the Siebel Institute have updated it, however, and always consider changes to improve it further.

Finally, I’ll comment briefly on the most important factor in flavor tasting: the individual taster.

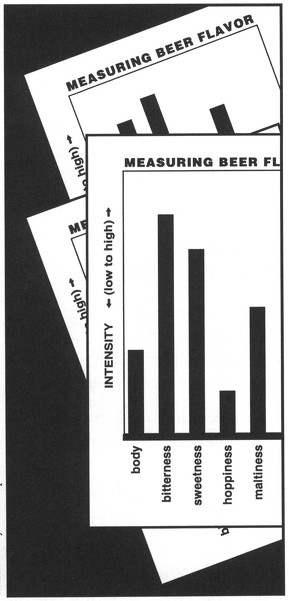

There are three important factors from the standpoint of tasting, the first of which is evaluation. Evaluating beer means going beyond simply asking if it is good or bad, do you like it or not. Evaluating is asking which components of your beer make it different from others, and how you can regulate the intensity of natural components—for example, the amount of hoppiness, bitterness, maltiness, etc.—to achieve the flavor you want.

Consistency is another factor that has caused brewers difficulty over the years. Consistency can be very elusive, but is probably the most important factor from a consumer’s standpoint. Therefore, it is necessary that you taste and profile your beer in order to detect minor changes in flavor and to monitor the consistency.

Finally, defects are important to identify so they can be isolated and corrected. For example, if you start detecting taste thresholds of diacetyl in your beer, you may wish to check your fermentation cycle and correct it before the taste becomes so manifest that it is detectable by consumers.

Glossary of Beer-Flavor Attributes

Fruity Perfumy fruit flavor resembling apples.

Hoppy Flavor due to aromatic hop constituents.

Bitter Bitter taste derived from hops.

Malty Aromatic flavor due to malt.

Hang Lingering bitterness or harshness.

Tart Taste sensation caused by acids, e.g. vinegar or lemon.

Oxidized Stale beer flavor. Resembles paperlike or cardboardlike flavor.

Medicinal Chemical or phenolic flavor, at times resembling solvent.

Sulfur Skunky—odor of beer exposed to sunlight.

Sulfur Dioxide—taste/odor of burnt matches.

Hydrogen Sulfide—odor of rotten eggs.

Onion—reminiscent of fresh or cooked onions.

Bacterial A general term covering off-flavors such as moldy, musty, woody, lactic acid, vinegar, or microbiological spoilage.

Yeasty Reminiscent of yeast, bouillon, or glutamic acid.

Diacetyl Typical butterlike flavor. The odor of cottage cheese.

Mouthfeel Sensation derived from the consistency or viscosity of a beer. For example, thin or heavy.

The glossary of beer-flavor attributes gives us definitions for specific flavors but is by no means inclusive. You need to build your own list of the attributes that are applicable to your situation, and the definitions that are meaningful to your tasters. If you set up a flavor profile, keep the number of attributes to a reasonable number. You’re better off dealing with fewer attributes and doing the job well than trying to taste a whole range.

These are some suggestions for definitions you might use when you first begin to develop a flavor profile.

The profiling system the Siebel Institute uses is not meant to be a standard, but it has been used successfully for many years. One of the first things that must be done is setting up an overall rating system. We use a nine-point hedonic scale, which runs from plus four to minus four, with zero being neutral.

Illustration by Vicki Hopewell

9-POINT SCALE OF PREFERENCE

+4 Like extremely

+3 Like very much

+2 Like moderately

+1 Like slightly

0 Neither like nor dislike

-2 Dislike moderately

-3 Dislike very much

-4 Dislike extremely

I recommend being as descriptive as you can in your overall ratings to help your panels be as descriptive as possible.

EXAMPLE OF A GRADING SYSTEM TO BE USED IN PROFILE EVALUATION OF A BEER

+4 The highest mark the taster can give. A sound, clean beer that strikes the taster “just at the right moment.” A grade this high reflects strong personal preference.

+3 A sound, clean beer and one for which the taster shows some personal preference. These preferences, such as the correct hop character, excellent aromatic quality, etc., should be clearly stated, if possible.

+2 An average, sound, clean, salable beer. If the taster can find nothing wrong with the beer, it should receive a “+2” rating and one should suppress his personal likes and dislikes for a thin or heavy beer, bitter or sweet, etc.

+1 A sound, clean beer and one which has no abnormal faults, but the taster feels some normal tastes are a little more pronounced (too bitter, too sweet, etc.) or a little too subdued (less hop, less body, etc.) than generally found. A faint trace of “normal” fault such as slight oxidation or a little too much of an SO2 character is permitted.

0 A beer in which you can find nothing in particular to praise and nothing in particular to fault. It can have faults but not of an intensity to cause the taster to reject the beer. A neutral type of beer.

-1 A beer with some abnormal defects present but at a mild level. The taster does not like the beer, but does not seriously reject it. A beer that is stale or abnormally harsh or slightly lightstruck or has a thermal induced character belongs here.

-2 Abnormal defects present, such as diacetyl, thermal-induced taste, lightstruck, can liner, medicinal, etc., at an easily detectable level, and the salability of the beer is questioned.

-3 Abnormal flavors present at a high intensity and probably cannot be eliminated by blending or the use of activated carbon. An objectionable beer.

-4 Undrinkable beer. You’ll know it when you taste it.

Page 80 shows our actual Taste Test Form. In tasting, we measure a total of thirty-five attributes, which might be a little too much for anyone not trained. The first five at the top are all compulsory qualities. When the taster profiles the beer, he must evaluate those qualities and make a mark in the category, based on the plus or minus for the type and style of beer. For example, if he’s tasting a lager beer, he’d judge it as an American lager. As such, it would be either staler or fresher than a normal lager beer; it would be thinner or fuller in body than a normal lager beer, etc.

The other compulsory marks are bitter and afterbitter, found in the middle of the sheet. Again, those are rated on the average for each particular type of beer.

The taster mentally changes this scale when he profiles a malt liquor, an ale, or a European lager. Obviously you can’t compare an American lager to another style of beer or a European lager. So the taster must shift gears.

Except for the seven attributes listed, every attribute is a voluntary marking. If the taster gets an impression, he notes the intensity level from one (mild) to four (strong).

Every attribute that falls below “yeasty” on this chart is considered a negative attribute or a defect.

There is also a place to comment on hop quality, odor, and other properties. These are the taster’s personal comments, made in addition to marking off the attributes and intensities.

The sheet should have a place for taster identification. We use a code, and date the sheet. We run three or four panels in a day, so we also indicate the panel and which side we tasted on.

This is an interesting point: we have ten tasters on our panel. We serve two packages of beer, so five people taste from each package. The obvious reason is that we can’t get enough beer out of one package. The unobvious reason is that there is occasionally package-to-package variation. It can be caused by high air in the package, for example. If we run into this situation, we have a retaste to determine how serious the variation is.

We rate up to seven beers on a panel. Beyond that number, the acuity of the taster diminishes. On the taste sheet, each column represents a different beer. Please consult the sheet on page 82. If there are no markings at the top, as in columns one, two, six, and seven, the beer is an American lager. As you can see, the beer in the third column is an ale, in the fourth a malt liquor, in the fifth a light beer. The brackets around columns one and two mean that tasters should specifically compare these two.

Normally, we drink the lighter beers first, moving on through the heavier beers—although on this taste sheet, it has been requested not to be that way.

All the compulsory categories have been marked. The shaded rectangle position represents the average for that type and style of beer. The first spaces note the minus and the last spaces represent the plus from the average.

At the bottom of the flavor profile is a numerical rating which is the nine-point hedonic scale mentioned earlier.

The Siebel Taste Test Form on page 82 is the actual form used after the taste panel evaluation. Seven beers were evaluated. Number one, two, six, and seven are the American lagers, number three an ale, number four a malt liquor, and number five a light beer.

In looking at the attributes of each beer, sample number one is an average American lager with no off-flavors and rates a plus 2.5. However number two shows oxidation with 2 intensity units of papery, bready, and aldehydic. There are also infected notes, diacetyl and sour and the beer was rated a minus 3. Clearly, the first lager is far superior. Sample number three, the ale, has more body and higher hop intensity. It shows a higher bitterness intensity than the average ale. The ale is also slightly oxidized and thus rates 1 intensity unit bready. The overall rating is a plus 1. The malt liquor, number four, shows all the normal malt liquor characteristics: sweet, alcoholic, higher esters, no detectable off-flavors, and a rating of plus 2.5. Number five, the light beer, is very stale and oxidized with 2 intensity units skunky but no infection. The beer has received a minus rating but not as low as the infected beer number two.

Once the evaluation sheet is turned in, the data is scanned by computer and a printout is received (see the Taste Panel Profile on page 86). Along the top of the sheet is the individual code for each of the eight tasters. If they made no response, a zero is entered, if they did respond, the level of intensity is marked with one, two, three, or four. At the bottom of each column is the number rating the taster gave the beer, as well as an overall rating for the beer. So, simply and quickly one can see the total intensity levels, the overall rating, the panel distribution, and any comments made by the taster. From this sheet the panel leader, who is responsible for the final report, will develop a final summary comment. The panel leader understands each individual taster’s acuity. If someone is very sensitive to diacetyl, for example, it will be noted and given more weight. The final computerized printout of the Initial Taste Profile is on page 87. The profile visually expresses the profile summary. All relatively normal attributes show their intensity units with solid dots. Below the term ‘yeasty’ is the listing of taste defects. Defect intensity units are denoted with stars. The numbers following the symbols note the intensity units (IU) and the number of tasters that commented.

The profile gives a clear overall analysis of the beer and is a particularly good format for comparing different beers.

In establishing the panel, make it a point to recruit people who have time to serve. Tasters need to be available and need to take the job seriously. Next, orient them to what you expect of them, giving them procedures, terminologies, profiles you use, etc.

Training is very important in establishing the panel. You must familiarize your panelists with the various tastes in beer, and explain the flavor evaluation vocabulary so everyone is speaking in the same terms. For example, they have to interpret “musty” as you do. Doctor a beer, let the panelists taste it, and then discuss it. Later you can test to determine levels of acuity.

As odd as it might sound, tasting a beer on a routine basis two and three times daily can become mundane. You have to keep your panelists motivated.

Performance is the key to good, successful tastings. You must monitor your panelists, and occasionally retest them to see that their acuities in different tastes have not diminished.

In selecting your panelists, choose people who are interested. If someone doesn’t want to taste, don’t force him or her into it. Health is pertinent. If the individual has allergies or health problems, that person will not be able to taste as well as someone who is healthy.

As in beer, the best taster is consistent. The taster must be so accurate and consistent that the person can duplicate results. You will find this out by doing periodic testing.

The panel should be held in a clean, quiet, well-lighted location. A cluttered office or a coffee room is not suitable. It should be pleasant, as the surroundings will definitely affect your tasters. It should also be convenient.

You certainly want a taste environment that is free from odors, as odors can have a residual effect. If there are lingering odors from cleaning solvents, tasters will not give accurate results.

Taste panel profile on Duesseldorfer Amber Ale

Lab number: 501904

Initial Tasting, Tested August 27, 1993

Received August 25, 1993

| d | y | j | q | b | s | h | z | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stale ←OXIDATION→ Fresh |

-1 |

-1 |

-3 |

-1 |

0 |

-1 |

- |

-2 |

-11 |

|

Thin ←BODY→ Full |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

3 |

|

Less ←FLAVORFUL→ More |

0 |

1 |

-2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Harsh ←PALATE→ Smooth |

-1 |

0 |

-2 |

-1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-6 |

|

Low ←HOP INTENSITY→ Hi |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

5 |

|

Vinous |

3 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Fruity, estery |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

13 |

|

Spicy |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Aley |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Alcoholic |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

BITTER, total |

3 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

29 |

|

Afterbitter |

3 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

28 |

|

SWEET |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Malty |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Caramel |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

DRY |

3 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

|

Astringent |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

|

Husk, grainy |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Worty |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sulfitic (SO2) |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Sulfidic (H2S, R-SH) |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

YEASTY |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

DMS, cooked vegetable |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

|

Light-struck, skunky |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Musty, cellar, woody |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Syrupy |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cardboard, papery |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

|

Burnt, scorched, bready |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Aldehydic |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Infected |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

Diacetyl |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

|

Sour |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Metallic |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Medicinal, phenolic |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Foreign, off |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Panel rating |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-2.0 |

+1.5 |

+0.5 |

+0.5 |

+0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

|

Distribution |

5/ 0 / 5 |

||||||||

|

Panelist |

Hop qualities |

Aroma |

Other properties |

||||||

|

d y j q b s |

|

||||||||

SIEBEL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

4055 West Peterson Ave., Chicago, IL 60646 (312)463-3400

INITIAL TASTE PROFILE

Lab number: 501904

Identity: Duesseldorfer Amber Ale

Customer code:

Date received: July 24, 1986

Date tested: July 25, 1986

|

Average |

||

|

Stale ←OXIDATION→ Fresh |

*********** |

-11 IU |

|

Thin ←BODY→ Full |

●●●3 IU |

|

|

Less ←FLAVORFUL→ More |

0 IU |

|

|

Harsh ←PALATE→ Smooth |

●●●●●● |

-6 IU |

|

Low ←HOP INTENSITY→ Hi |

●●●●● 5 IU |

|

|

Vinous |

●●●●●● 6 IU, 3 Panelists |

|

|

Fruity, estery |

●●●●●●●●●●●●● 13 IU, 8 |

|

|

Spicy |

● 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

Aley |

● 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

Alcoholic |

● 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

BITTER, total |

●●●●●●●●●●●●● ●●●●●●●●●●●●● ●●● 29 IU, 10 |

|

|

Afterbitter |

●●●●●●●●●●●●● ●●●●●●●●●●●●● ●● 28 IU, 10 |

|

|

SWEET |

●●● 3 IU, 3 |

|

|

Malty |

●●● 3 IU, 3 |

|

|

Caramel |

●●●●● 5 IU, 4 |

|

|

DRY |

●●●●●●●●● 9 IU, 4 |

|

|

Astringent |

●●●●●●●●● 9 IU, 5 |

|

|

Husk, grainy |

●●●● 4 IU, 3 |

|

|

Worty |

||

|

Sulfitic (SO2) |

●●● 3 IU, 1 |

|

|

Sulfidic (H2S, R-SH) |

●●● 3 IU, 1 |

|

|

YEASTY |

● 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

DMS, cooked vegetable |

**** 4 IU, 4 |

|

|

Light-struck, skunky |

||

|

Musty, cellar, moody |

**** 4 IU, 3 |

|

|

Syrupy |

||

|

Cardboard, papery |

**** 4 IU, 3 |

|

|

Burnt, scorched, bready |

********** 10 IU, 8 |

|

|

Aldehydic |

**** 4 IU, 1 |

|

|

Infected |

**** 3 IU, 3 |

|

|

Diacetyl |

******** 8 IU, 5 |

|

|

Sour |

* 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

Metallic |

||

|

Medicinal, phenolic |

* 1 IU, 1 |

|

|

Foreign, off |

||

Panel rating:-0.2

Panel distribution: 5 / 0 / 5

Comments: Stale, oxidized flavor. Harsh and astringent. Malty with DMS notes.

Reviewed by: Ilse Shelton

(C) Siebel Institute of Technology

Approval Needed for Reproduction

One factor for consideration in setting up the panel is the color of the beer glasses. We at Siebel Institute use ruby red glasses, for example, because we don’t want panelists to evaluate the physical characteristics of the beer—i.e., the foam, clarity, color, etc.—during tasting. They are there to taste and taste only. Physical qualities are quantified in the lab.

Our panelists normally drink beer starting with the one on the left and move toward the right. Therefore we place the lighter beers on the left, so tasters move from lighter to heavier progressively.

You should also give your panelists special instructions if there are any. We list them on a blackboard, rather than state them. There are also a few panel rules. We ask the tasters to refrain from making comments during the actual taste test. This includes smacking lips or retching. We also ask panelists to be on time to tastings, so that the test is not disrupted or postponed.

Finally, no taster is allowed to change his marks once the test is over. When each panelist is finished, he lays the sheet down. When everyone has finished, they discuss the beer.

No matter how large or small your brewery is, you don’t need expensive or complicated tasting equipment to conduct a valid testing. In fact, you already have the most sophisticated instrumentation for tasting beer—your own sense of taste and smell. The only problem in a smaller brewery is that you have fewer people to rely on for tastings. Perhaps you can exchange beers with someone for tasting, or periodically send your beers out.

Brewers should train themselves to evaluate beer. If there is one thing I’d do in running a brewery, it is get very proficient in identifying certain flavors, and particularly defect flavors. Then I could recognize them when they first occurred, hopefully in time to take action.

Finally, producing a high-quality beer, consistently, is the best thing you can do to ensure the sale of your beer.