You do get to a certain point in life

Where you have to realistically, I think,

Understand that the days are getting shorter.

And you can’t put things off,

Thinking you’ll get to them someday.

If you really want to do them,

You better do them….

So I’m very much a believer in knowing

What it is that you love doing

So that you can do a great deal of it.

—Nora Ephron (1941–2012)

Make no mistake. This isn’t just a matter of staring at your navel. This is a job-hunting method—the most effective one, at that. This method, faithfully followed, step by step, works 86 percent of the time. That means that out of every 100 job-hunters or career-changers who faithfully execute this job-hunting method, 86 will get lucky and find a job thereby; 14 job-hunters out of the 100 will not—if they use only this method. Note well: You have a twelve times better chance of finding work using this method, than if you had just sent out your resume. Not just work, but work you really want to do. What we sometimes refer to as “our dream job.”

Why does an inventory of who you are, work so well in helping you find work, after traditional job-hunting methods have failed? That’s important to know, because the answer will keep you motivated to finish this inventory, when otherwise you might say, OMG, this is just too much work! And just give up.

Okay, here are seven answers as to why this works so well:

By doing this homework on yourself, you learn to describe yourself in at least six different ways, and therefore you can approach multiple job markets. Retraining, as it is commonly practiced in Western culture, prepares you for only one market. Thus someone decides that out-of-work construction workers should be retrained, let us say, to be computer repair people. Hence, their job-hunt approaches only one market. And if no jobs can be found in that market, once they are trained? Retraining wasted. This is why retraining programs sometimes acquire such a bad reputation.

But with an inventory of who you are, you stop identifying yourself by only one job-title. You can now think of yourself as not just “a computer repair person,” or “a construction worker” or “accountant” or “engineer” or “minister” or “ex-military” or whatever. You are a person who has these multiple skills and experiences. If, say, teaching and writing and growing things are your favorite skills, then you can approach either the job market of teaching, or that of writing, or that of gardening. Multiple job markets open up to you, not just one.

By doing this homework on yourself, you can describe in detail exactly what you are looking for. This greatly enables your friends, LinkedIn contacts, and family, to better help you. You approach them not with, “Uh, I’m out of work; let me know if you hear of anything,” but with a much more exact description of what kind of “anything,” and in what work setting. This greatly helps them to focus down, and look for something very specific, thus increasing their helpfulness to you, and your ability to find jobs you would otherwise never find.

By ending up with a picture of a job that would really excite you, and not just any old job, you will inevitably pour much more time, energy, and determination into your job-search. This is really worth looking for. So, you will redouble your efforts, your dedication, and your determination when otherwise you might try but soon give up. Persistence is the essence of a successful job-hunt, and persistence becomes your middle name, once you’ve identified a prize worth fighting for.

By doing this homework, you will no longer have to wait to approach companies until they say they have a vacancy. Once done with this homework, you can choose places that match who you are, and then approach them (through a contact, or what I like to call a “bridge-person” because they know both you and them, and thus serve as a bridge between you)—knowing confidently that you will be an asset there, if they turn out to have a job opening or decide to create one for you.

Create one for you? No, I’m not kidding. This happens more often than you would ever think, to the prepared job-hunter or career-changer. Wrote one job-hunter to me recently:

In my mind I knew where I wanted to work: a company I had had a couple of meetings with about an imperfect job about two years ago and fell in love with. I found the CEO on LinkedIn, asked him if he remembered me and would he be up for a short meeting if I promised it would be fun. He said he would love to meet and I pitched the idea of setting up a training academy for them. About a month later, I had an email to say they definitely want to go ahead with providing training as I had pitched it. The job did not exist, they had not conceived of the job, and it meets all my criteria because I thought of it. [From] Parachute to dream job in six months is not bad is it?

When you are facing, let us say, nineteen other competitors for the job you want—equally experienced, equally skilled—you will stand out above them all, because you can accurately describe to employers exactly what is unique about you, and what you bring to the table that the others do not. These will usually turn on adjectives or adverbs, what we normally call traits. More on that, in the next chapter.

If you are contemplating a career-change, maybe—after you inventory yourself—you will see definitely what new career or direction you want for your life. Often you can put together a new career just using what you already know and what you already can do—with much less training or retraining than you thought you would have to do. I’m not talking about a dramatic change, like going from salesperson to doctor: for that, you will need to start over. But most career-changes are not that dramatic, as I will show you, in chapter 11. But first, please, please, inventory who you are and what you love to do.

It may turn out that the knowledge you need to pick up can be found in a vocational/technical school, or in a (one- or) two-year college.

And sometimes, sometimes, it can be found simply by doing enough informational interviewing (more about this in chapter 8). Example: A job-hunter named Bill had worked for a number of years in retail; now he was debating a career-change—working in the oil industry. But he knew virtually nothing about that industry. However, he went from person to person who worked at companies in that industry, just seeking information about the industry. The more of these “informational interviews” he conducted, the more he knew. In fact, coming down the home stretch, just before he got hired in the place of his dreams, he found he now knew more than the people he was visiting, about their competitors and some aspects of the industry.

In other words, with certain kinds of career-change, there is more than one way to pick up the knowledge you need.

Unemployment is an interruption, in most of our lives. And interruptions are opportunities, to pause, to think, to assess where we really want to go with our lives. Martin Luther King Jr. had something to say about this:

The major problem of life is learning how to handle the costly interruptions. The door that slams shut, the plan that got sidetracked, the marriage that failed. Or that lovely poem that didn’t get written because someone knocked on the door.

A self-inventory is just that type of thinking and assessing.The Parachute Approach, with its demand that you do an inventory of who you are and what you love to do, before you set out on your search for (meaningful) work, helps you take advantage of the opportunity that this interruption presents.

So there you have it: the seven reasons why this inventory of who you are, works so much better as a method of job-hunting than all other methods.

Being out of work, or thinking about a new career, should speak to your heart. It should say something like this:

Use this opportunity. Make this not only a hunt for a job, but a hunt for a life. A deeper life, a victorious life, a life you’re prouder of.

The world currently is filled with workers whose weeklong cry is, “When is the weekend going to be here?” And, then, “Thank God it’s Friday!” Their work puts bread on the table but…they are bored out of their minds. They’ve never taken the time to think out what they uniquely can do, and what they uniquely have to offer to the world. The world doesn’t need any more bored workers. Dream a little. Dream a lot.

One of the saddest pieces of advice in the world is, “Oh come now—be realistic.” The best parts of this world were not fashioned by those who were “realistic.” They were fashioned by those who dared to look hard at their wishes and then gave them horses to ride.

These are the things you will need:

You begin by stripping yourself (in your mind) of any past job-titles. When you ask yourself “Who am I?” you must drop the vocational answer that first springs to mind. Like: I’m an accountant, or I am a truck driver, or a lawyer, or a construction worker, or salesperson, or designer, or writer, or account executive. That kind of an answer locks you into the past. You must think instead: “I am a person…”

“I am a person who…has had these experiences.”

“I am a person who…is skilled at doing this or that.”

“I am a person who…knows a lot about this or that.”

“I am a person who…is unusual in this way or that.”

Yes, this is how a useful self-inventory begins. You are a person, not a job.

Brain researchers such as Barbara Brown of USC discovered that when you are trying to make any kind of decision about your life, the most effective strategy is to shrink down every significant thing you know about yourself onto one piece of paper.1 At least at the end. Not a journal, or a bunch of Post-It Notes, or several pieces of paper. Just one. (Write small.)

In this book that one piece of paper that you end up with, is called The Flower Exercise, or Flower Diagram.

As you are working your way toward summarizing everything important about yourself on just one piece of paper, you are going to need along the way a number of disposable blank pieces of paper—I call them worksheets—in order to do a particular exercise (or two) that I will show you, for each flower petal. I emphasize disposable. You will ultimately be copying the final results from these worksheets onto your Flower Diagram, after which you can recycle these worksheets. For these worksheets, you are going to need to get a bunch of 20 lb. blank sheets of paper.

Again, brain researchers discovered that it helps immensely in making a decision about your life, if you don’t just put a flood of words on that one piece of paper, but add some kind of a graphic, picture, or diagram. They discovered that this encouraged the right side of your brain, to spring into action—the part of your brain that can look at a whole bunch of apparently unrelated data and exclaim “Aha! I see what it all means.” Some like to call this your intuitive side, the opposite of your logical side.

In the workshops that I taught from 1970 to 2012, I encouraged my students to choose any graphic they wished. We needed a picture with seven parts to it, corresponding to the seven parts of you that are important in finding matching work. Well, the favorite graphic turned out to be a picture or diagram of yourself as a flower, with a center and six other petals. Hence the title of our self-inventory: The Flower Diagram (or Flower Exercise).

It is easy to imagine that the purpose of a self-inventory is to gather a series of personal lists, to which you then try to match possible jobs or careers. For example, “Here’s a list of all the things I want in my place of work.” Or: “This is a list of all the skills I want to be able to use at my next job, or career.” But over the past forty years or so, we have discovered that lists are useless, unless and until the items on each list are put into order of priority or importance for you: this item is most important to me, this is next most important, next, then next, etc.

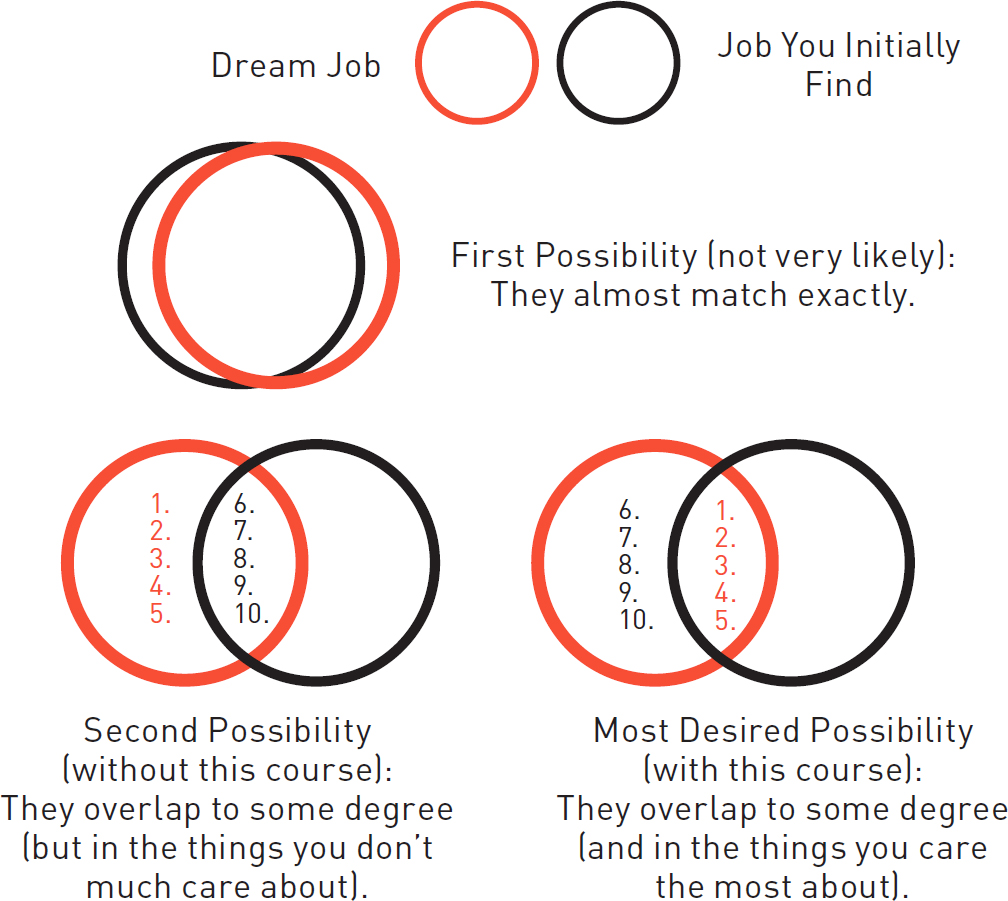

And why is this? Well, we live in an imperfect world, and—at least initially—you may not be able to find a match for all the items on your lists. You may only be able to find a match for some of the items. There will be only a partial overlap between “dream job” and “actual job,” in which case it is important that the overlap be the items you care the most about, not the least. And how will you know that, unless you put the items on each list in order of importance to you?

Here is the problem visually summarized:

Okay, so prioritizing is essential. How do you go about this? Having compiled a list of, say, ten items on one of the petals in your Flower Diagram, how do you decide which of the ten is absolutely the most important to you, which of the ten is next most important, etc.? It seems at first sight a bewildering challenge. Actually, it’s easier than you think, if…

If…you compare just two items at a time, until you’ve compared all the possible pairs in that list of ten items. With all the pairs displayed in one diagram, this works out to be a grid. And the most popular form of that grid turns out to be my Prioritizing Grid, which I invented back in 1976. It can be for any number of items you choose, but the most common and simplest form of it is for ten items. (Got more than ten—or less? See http://www.beverlyryle.com/prioritizing-grid for instructions.)

Anyway, this page shows what a ten-item Grid looks like, once it is completed. As you can see, this example deals with a ten-item list of “People I’d Prefer Not to Have to Work With.” (You will produce this list, or one like it, by means of an exercise you will find in the next chapter, reviewing your past experiences.) I’ll use this example to illustrate how you use any ten-item Grid.

(I originally had more than ten items as a result of that exercise, but by guess and by gosh I narrowed them down to my top ten, and then worked just with them, here.)

Section A. Here I put my list of ten items, in any order I choose. So, as you can see, the people I’d prefer not to have to work with, are those who are: bossy, never thank anyone, are messy in dress or office space, claim too much, are uncompassionate, never tell the truth, are always late, are totally undependable, feel superior to others, or never have any ideas. The order in which I list these items here in Section A doesn’t matter at all.

Section B. Here are displayed all the possible pairs among those ten. Each pair is in a little box, or rather the numbers that represent each pair, are in a little box. You ask each box a question. The framing of the question is crucial. The question you address to each box is: “Between these two items, which is more important to me?” Or, since this is a Grid of dislikes, “Which of these two do I dislike more?” (Think of choosing between two hypothetical jobs.)

Let’s see how this works. We’ll start with the first little box at the top. The box has the numbers 1 and 2 in it. (#1 stands for bossy, while #2 stands for never thanks anyone). So, the question is: Which do you dislike more: #1 or #2? You circle your preference—in that box. I circled #1—as you can see—because I dislike being around bossy people at work more than I dislike being around ungrateful people.

You go on now to the second box (down diagonally to the southeast) which has in it the second pairing, in this case, the numbers 2 and 3. The question again: Which do you dislike more? I circled #3 in that box—as you can see—because I dislike being around messy people at work more than I dislike being around people who never thank anyone.

And so it goes, until you’ve circled one number in each little box in Section B.

Section C. Section C has three rows to it, at the bottom of the Grid, as you can see. The first row is just the ten numbers from Section A.

The second row is how many times each of those numbers just got circled in Section B. As you can see, item #1 got circled 7 times, item #2 got circled 1 time (as did item #10—a tie—so, to break the tie I look up in section B to find the little box that had both #2 and #10 in it, to see which I preferred at that time, and I see it was #2, so I give #2 an extra ½ point here, over #10). Item #3 I notice got circled three times, but so did item #4 and item #7—a three-way tie! How to break that tie? Well, here you’ll just have to do some guessing. I guessed these were important to me in this order: #4, #7, and then #3. So, I added ½ point to #4 and ¼ point to #7; I left #3 as it was.

In the third and bottommost row of Section C, I put the ranking according to the number of circles in the second row. Item #6 got the most circles—9—so it is number 1 in ranking. Item #8 got the next most circles—8—so it is number 2 in ranking. And so it goes, until that whole bottom line is filled in. Now the only task remaining on this Grid is to copy the reorganized list onto Section D.

Section D. The aim here is to relist my ten items (from Section A) in the exact order of preference or priority, for me, using Section C as my guide. Item #6 got the most circles there, and it ranked number 1, so I copy the words for item #6 in the number 1 position in Section D. Item #8 ranked second, so I copy the words for item #8 into the second spot in Section D. Etc. Etc.2 What I am left with, now, in Section D, is the ten items in the exact order of my preference and priority. Nice! I can copy them all now—or at least the first five—onto my Flower Diagram in the next chapter. I now know what should be in the overlap between my dream job and the job I initially find, if I am to be happy and effective in that job.

Where can you find blank copies of this Prioritizing Grid? Here are the three main places:

• In this book. A ten-item paper version appears throughout the next chapter, which you can download here. Plus, since some copy centers will not allow you to copy items out of a book without permission, tell them you have my permission to copy or reproduce that Grid as many times as you wish, for your own private use (not for inclusion in an e-book or another published work).

• In a workbook. Its title is What Color Is Your Parachute? Job-Hunter’s Workbook. $12.99 online or at bookstores; another paper version, but its advantage here is that the workbook pages are larger—8 x 10.

• Online. We are working on an elegant web version of the Grid; can’t say how soon it will be done. Meantime, I have given my friend Beverly Ryle permission to produce a simpler online version of my Prioritizing Grid, that is automated and interactive. It is found at www.beverlyryle.com/prioritizing-grid and it is free. You can use my ten-item Grid there, or customize a Grid for any number (of items) you choose. Needless to say, you can use her website as many times as you wish, and print out the results each time for your own keeping.

Before you go on to fill in the petals in the next chapter, it is sometimes helpful to ask yourself: in the abstract which petals—which parts of a job—do you instinctively feel are most important to you—at least for now—and in what order?

the salary?

the geographical location?

the people you work with?

the look and feel of your workplace?

the degree to which it gives you a sense of purpose for your life, or fits in with the purpose you want your life to serve?

the degree to which it lets you use your favorite skills, abilities, or talents?

the degree to which this job lands you in your favorite field or fields of knowledge and interest?

You can just guess in what order these are important to you. Or you can use a seven-item Prioritizing Grid to get this exactly right. (For a paper version, take a ten-item Grid, draw a horizontal line in Section B, just below the seventh item in Section A, and don’t use any boxes in Section B that are below that line. Or if you have access to the Web, you can go to Beverly Ryle’s website, and create a customized interactive seven-item Grid, found at www.beverlyryle.com/prioritizing-grid.)

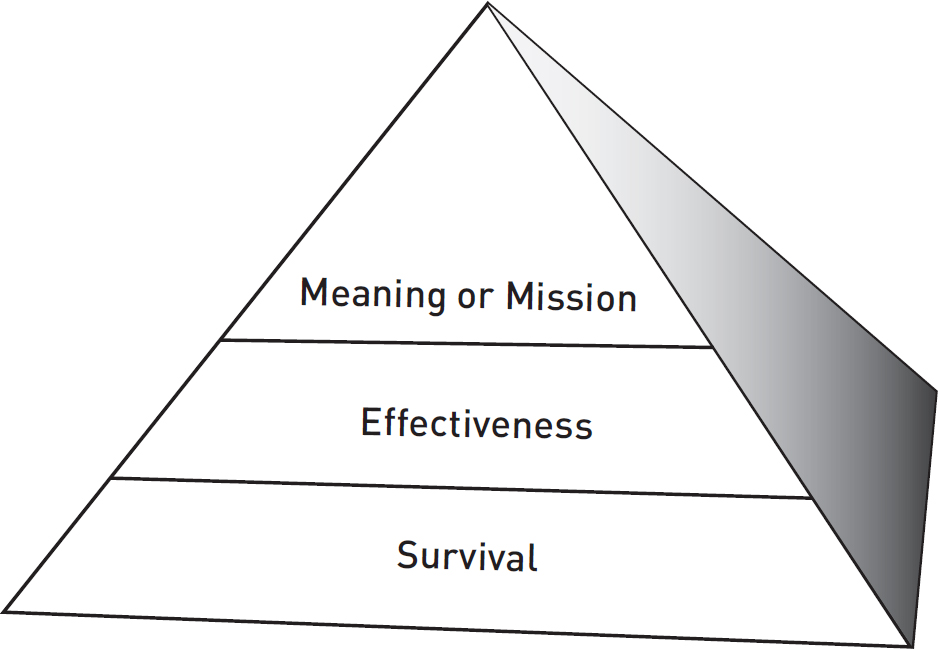

If you want to know which petals other people have most often picked as their first priority in the past, the answer varies. A lot depends on where you are in your life, and which issue you are most preoccupied with, on this chart:

If they’re just trying to survive, their first choice is usually the Salary petal. If they’re on in years, it’s the Purpose petal. If they’re anywhere in between, it’s the petals dealing with abilities/talents/skills. But all seven petals are important to you; don’t leave any of them out.