POLLSMOOR MAXIMUM SECURITY PRISON

MARCH 1982–AUGUST 1988

Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba, and Andrew Mlangenii were transferred on 31 March 1982 from Robben Island to Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison on the mainland, where they were held in a large communal cell. Shortly after their arrival, Mandela wrote to the ‘kitchen department’ to inform the staff of his dietary requirementsii and then to his lawyers in case they were not aware that he was now in another prison. They were joined in Pollsmoor Prison by Ahmed Kathrada on 21 October 1982. Mandela said he was never told why they were all transferred. He asked the commanding officer who replied that he could not say.

‘I was disturbed and unsettled. What did it mean? Where were we going? In prison, one can only question and resist an order to a certain point, then one must succumb. We had no warning, no preparation. I had been on the island for over eighteen years, and to leave so abruptly?

‘We were each given several large cardboard boxes in which to pack our things. Everything that I had accumulated in nearly two decades could fit into these few boxes. We packed in little more than half an hour.’58

A large face-brick prison complex nestling at the foot of the mountains outside Cape Town, with beds and better food, Pollsmoor was in a way a tougher existence for the men. Gone was the open space they had walked in from the cell block to the lime quarry; or down to the seashore to harvest seaweed. Separated from the rest of the prison population, they were held in a rooftop cell and could only see the sky from their yard.

To the head of prison, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison

D220/82i: NELSON MANDELA

The Head of Prison,

Pollsmoor Maximum Prison

Attention: Kitchen Department

Kindly note that for health reasons I am on a salt free diet. I am also not on eggs.

[Signed NRMandela]

[not dated but the date handwritten by a prison official is 82/04/20]

[In another hand in Afrikaans] Dealt with

[Signed] W/Oii Venter

To the head of prison, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison

D220/82: N MANDELA

21.1.83

The Head of Prison,

Pollsmoor Maximum Prison.

Attention: Captain Zaayman

I must ask you to investigate, once again, the question of the letter which Prof. Carteriii wrote to me, the censoring of the letter from Mrs Mgabela,iv as well as the three other issues mentioned below. I repeat this request in the hope and confidence that you will re-examine these questions with the detachment and understanding they deserve.

I must stress that the reply I received in response to my representations to you suggests that despite the care and patience with which I explained the whole matter, in fact you did not understand me and accordingly misdirected your enquiries.

1. Letter from Prof. Carter

On the two previous occasions I raised this particular matter with you, I pointed out that Prof. Carter had written to me in May last year after she had read press reports that I had been transferred to this prison. I further pointed out to you that the letter was probably lying in some office in this establishment and that you might be able to trace it in the course of a proper search.

But then the other day the warder in charge in this section read me a written note, purporting to come from you, to the effect that Robben Island Prison had informed you that no letter from Prof. Carter had been received. In view of the fact I expressly explained to you that the letter had been addressed to this prison, I could not understand why Robben Island was ever brought in. I must, therefore, request you to look into this matter again and to advise me of the results of your enquiry in due course.

2. Letter from Mrs Mgabela

You did not respond at all to my request relating to this question. But in the notes which were read out to me by the warder in charge there was a message to Mr Magubela which appeared to be your response to the request I had earlier made to you on the same issue.

You will readily appreciate that it is not easy for one to comment with regard to the actual words which were deemed by the censors to be objectionable. But what is perfectly clear is that either your failure to respond to me or the error you made is certainly no evidence you gave the matter the attention it deserves.

3. Letter from Mrs Njongwei

About a week or so before Christmas I received a Christmas card from Mrs Njongwe in which she said I should expect a letter from her. In this connection, I will appreciate it if you will be good enough to advise me whether the letter has been received.

4. Heads of Argument in the case of myself v. the Minister of Prisonsii

Again, you have not responded in this matter. As you are aware this is a different question from the one you referred to Pretoria.

5. Letter from Mrs Mandela

When my wife visited me on Christmas Day she brought me a letter addressed to her from an organisation of women from the U.S.A. When she was refused permission to show it to me, she promised to post it from Cape Town. Please advise me whether the letter has been received.

I wish to indicate in conclusion that I would really like to settle these and other matters falling within your jurisdiction directly with you, and not to burden the Commanding Officer about issues which you can easily and satisfactorily dispose of. It is in this spirit that I request you to go into these matters, and it is to be hoped that you will handle them in this spirit.

[Signed NRMandela]

[Handwritten note in another hand] Warrant Officer Gregory. Refer this matter to Captain Zaayman.

[Signed]

83/02/25

To the head of prison, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison

D220/82: N MANDELA

25.2.83

The Head of Prison,

Pollsmoor Maximum Prison.

Attention: Major Van Sittert

The warder in charge of this section advises me that you have instructed that no woollen head-cover should be bought for me, and that I will be allowed to select a suitable hat from several kinds supplied by the Prisons Department.

I trust that you will be able to reconsider your decision and that you will not refuse a recommendation made by a specialist physician and from a medical practitioner attached to this prison; recommendations which are based on medical and humanitarian considerations and on grounds of convenience.

The plaster and stitches were removed from the woundi on 14th February and I have been battling to get a head cover since that day. It is, to say the least, indifference on the part of this Department to withhold from me, for so long, an article which will facilitate recovery.

I have already tried to wear a prison hat and it has proved totally unsuitable. Its effect has only been to make a sensitive wound even more sensitive, apart from the fact that I cannot sleep wearing a hat.

I have the confidence that you will be good enough not to use your authority as to make me a caricature of myself by compelling me to see my family and legal representatives without a suitable head cover.

[Signed NRMandela]

To Russel Piliso, his brother-in-law and husband of his sister Leabieii

[Translated from isiXhosa]

D220/82: N MANDELA,

29.6.83

Dear brother-in-law,

I received the response from Miss Leabie giving me feedback on the role you played during the burial of my sister Baliwe. I received the news of her death in a telegram from Bambilanga,iii which I quickly responded to. Miss Leabie’s letter came after I had sent my letter of gratitude to Bambilanga. There is only one thing I would like to say to you, and that is to echo the words of our elders, ‘I thank you’.iv As you are aware, my present circumstances do not allow me to say anything further; however receive my heartfelt condolences.

Again, I thank you.

Please pass my sincerest regards to Miss Leabie, Phathiswav and the rest of the family. Yours truly, Madiba

9.3.84. This letter was written on 29.693

[envelope]

Mr Russel S. Piliso

S.A.P.

Tsolo

P.O. Tsolo, TRANSKEI

To Adele de Waal, a friend of his wife, Winnie Mandela

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

29.8.83

Dear Adele,

[Written in Afrikaans] My knowledge of Afrikaans is very bad and my vocabulary leaves a lot to be desired. At my age I am struggling to learn grammar and to improve my syntax. It would certainly be disastrous if I wrote this letter in Afrikaans. I sincerely hope you will understand if I change to English.

[Written in English] Zamii has told me several times of the interest you and Pietii have shown in her problems over the past 6 years. Although I have on each occasion requested her to convey my appreciation to you, the beautiful and valuable present of books you sent me has given me the opportunity of writing to thank you directly for your efforts.

It was certainly not so easy for her at middle-age to leave her home and to start life in a new and strange environment and where she has no means of earning a livelihood. In this regard, the response of friends has, on the whole, been magnificent, and it made it possible for her to generate the inner strength to endure what she cannot avoid. We were particularly fortunate to be able to count on the friendship of a family that is right on the spot and to whom she can turn when faced with immediate problems. [Written in Afrikaans] You and Piet have contributed significantly to her relative safety and happiness. [Written in English] I sincerely hope that one day I will be able to join you in your village and shake your hands very warmly as we chat along.

[Written in Afrikaans] Schalk Pienaar’s book Witness to Great Times is one of the books on the shelf. On page 13 there is a reference to a farmer,i Pieter de Waal, who participated in the 1938 oxwagon trek to Monument Hill. According to the story he succeeded to calm a group of restive trekkers in Oggies in the Free State. Perhaps he was Piet’s father or grandfather.

[Written in English] Whenever Piet’s name is mentioned, especially when I receive a letter from him, I instinctively think of a friend, Mr Combrink, from that world who probably is now running a flourishing legal firm. I last saw him about 30 years ago when he used to work in a dairy during the night and as an articled clerk during the day. Perhaps Piet will be able to give him my regards if and when he meets him.

Meantime, I send you, Piet and the children my fondest regards, and hope that your daughter is doing well in England.

Sincerely,

Nelson.

Mrs Adele de Waal, Duke Street, P.O. Brandfort, 9400.

To the commissioner of prisons

[This letter is in Ahmed Kathrada’s handwriting but signed by Mandela]

6th October 1983

The Commissioner of Prisons

Pretoria

Sir,

We have been informed by the local authorities that in accordance with an instruction from Prison Headquarters, prisoners who are taken to doctors, hospitals, courts etc. will in future be handcuffed and put in leg irons. We are told that this is to be applied to all prisoners, i.e. security prisonersi as well as common law prisoners.

We wish to make an earnest appeal to you to reconsider your decision relating to security prisoners, and allow the present position to continue.

During the 20 years that we have spent in prison there have been numerous changes in our treatment. Previously we had been handcuffed when we were taken from Robben Island to Cape Town, but for a number of years this had been discontinued. We welcomed and appreciated the discontinuance, as we welcomed all changes that were designed to alleviate the hardships of prison life and make our stay more tolerable. Of special concern to us was the removal of practices which were not only outdated but which were unnecessarily burdensome and humiliating.

While we do not wish to comment on the general security arrangements of the Prisons Department, we nevertheless wish to make some observations in support of our present appeal.

1) To the best of our knowledge, during the entire period of our incarceration there has not been a single instance where a security prisoner has escaped, or even attempted to do so, while being escorted to Cape Town for medical reasons.

2) For the year and a half that we have been at Pollsmoor our experience has been that each time any of us was taken out, he was invariably accompanied by four or more warders, some armed. Often the warders were accompanied by a member of the Security Police.

3) This elaborate arrangement has been strictly applied in spite of our advanced ages and physical condition.

4) In our opinion such arrangements were, and still remain, quite adequate and the additional restraints are totally unwarranted, burdensome and humiliating. This is aggravated by the great deal of attention and curiosity that is aroused among the public at the sight of handcuffed prisoners.

5) We are certain that Robben Island and Pollsmoor authorities will be able to bear out our contention that security prisoners could not be accused of having abused the “medical outings”.

6) It has been pointed out to us – and recently with greater emphasis – that there is no distinction in the treatment of prisoners irrespective of whether they are common law or security prisoners.

7) With respect, Sir, may we remind you that this is not strictly in accordance with the factual position. For example, security prisoners are denied the privilege of contact visits, and, generally even though they may be classified as “A Groups” they suffer from restrictions in their day to day stay. Perhaps more important; security prisoners on the whole are being denied the facilities for remission and parole enjoyed by other prisoners. We believe that the few to whom this dispensation was extended were given remission ranging from a couple of weeks to a few months.

8) We submit that since differential treatment does in fact exist, there should be no reason why security prisoners should not be exempted from the instructions regarding handcuffs and leg irons.

9) Lastly, from the point of view of health we consider these new arrangements to be a decided disadvantage. A number of us are suffering from high blood pressure, and it is important that when we are taken to specialists we should be relaxed and completely free of tension. It is likely that the humiliation and resentment caused by handcuffs will adversely affect our blood pressure. To an extent, therefore, this would be defeating the purpose [of] our consulting the specialists.

We respectfully state that we cannot think of a single valid reason why this new restriction should be applied to us, and we once again appeal to you to abandon them.

Thank you,

Yours faithfully

[Signed NRMandela]

N.R. Mandela

To Fatima Meer,i a friend

[Stamp dated 30.1.84]

Our dear Fatimaben,i

Arthur & Louise Glickman c/o Glickman farm R.F.D. 2, Clinton, Maine, 04927, U.S., have twice sent me a cheque but without a covering note. Although I asked Zamiii to write & thank them on my behalf, it is proper for me to add to what she has said to them. But my main difficulty is that I have not information on them other than the particulars that appear on their cheques. You will be the best person to contact them & thereafter send me the particulars at your earliest convenience.

Our niece, LWAZI VUTELA, a teenage daughter of Zami’s late elder sister, is also over there. She is a second yr student at Wellesly College, Box 128, McAfee Hall, Wellesley M.A., 02181, U.S.A. I don’t know just how far her college is from Swarthmore,iii but I will be happy if you can see her & perhaps introduce her to some of your friends there.iv

She tells me that she has written me several letters from the States, all of which I never received. She adds that most of the time she is lonely & homesick, which is quite understandable for a person of her age. She will find your advice on both academic & personal matters valuable.

Talking of people in the U.S.A., I was very disturbed when I read in the Time Magazine that our friend, Senator Paul Tsongas, from Massachusetts, is suffering from some form of cancer & that, as a result, he will not seek election for a second term in Nov. As you know, he has visited Zami in Brandfort & has, in the process, become a good family friend. I was sorry to learn of his illness & sincerely hope that the illness was detected in time & that he will recover completely in due course. As you know, I cannot write to him & all that I can do is to ask you to give him our good wishes & fondest regards. Do you hope to see professors Gwen Carterv & Karis?vi

I trust that it will be possible for you to visit the holy city of Mecca & Tehran & New Delhi. I would have written to Indiravii long ago but, as you know, she is among those who are beyond my reach in terms of my current circumstances.viii From this distance she seems to be doing exceptional[ly] well & I always read news about her with great interest.

My fondest regards to her.

What is Rashidix doing now & where? You have kept me informed about the girls but given away very little on the heir.

Needless to say, in my current circumstances it is not easy to appreciate precisely what game Bansii is now playing. Whatever it may be it seems to me that he has chosen a pitch more likely to favour batsmen George,ii Archie,iii Faroukiv & others rather than him, Pat,v J,vi B & YS.vii

The Chancellorship!viii I had already exhausted my 1983 quota of outgoing letters when your telegram came, & my response was limited to the special brief note of acceptance that I sent to you and the principal. This is the very first opportunity I have to thank you & all those who supported our candidature for the office. I am, however confident that everybody was from the outset well aware of the real issues involved, & that it is unrealistic, at this stage in the country’s history, to expect an incarcerated black candidate to be elected Chancellor of a white university, especially of Natal where apparently the Senate, & not members of Convocation, has the final say on the matter. Maybe that on your return, it will be possible for you to investigate, if that is possible, exactly what measure of support we enjoyed. Meantime do give everybody our sincere appreciation & thanks.

I have not heard from Makiix for quite some time now. But she promised to start this mnth & I hope you fully briefed Ismailx on her before your departure.

Coming back to you, it seems that I must congratulate you in every letter that I write to you. In my last letter I congratulated you on your appointment as Prof; press reports indicate that Swarthmore will honour you with a doctorate, an honour, which in my view, you rightly deserve. This is more than a triumph of Women’s Lib & I fear that poor Ismail had joined those husbands who are known more through their wives. There must be many who now refer to him as “Fatima’s husband”. I miss him very much & I was very happy when press reports indicated that he was one of the speakers in Mota’sxi commemoration service. This is a very long letter & I must now stop so that you can rest a bit. Tons & tons of love Fatimaben.

Very sincerely, Nelson.

Kindly register all your letters to me.

To Trevor Tutu, son of Desmond & Leah Tutui

[This letter was retyped in a telexii to the Commissioner of Prisons]

[Note in Afrikaans] Confidential

913

Commissioner of Prisons

AK Security

For immediate delivery to Brig Venster please

1. The prisoner is still trying to make contact with Bishop Desmond Tutu. He is now writing to the Bishop’s son, Trevor Tutu, and is in this way attempting to contact the Bishop.

2. Below find the contents of the letter

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA |

Pollsmoor Maximum Prison |

|

P/B X 4 |

|

TOKAI |

|

7966 |

|

84.08.06 |

My dear Trevor,

It was shocking to learn that your home was attacked and damaged, and I sincerely hope that the knowledge that you and your parents are constantly in our thoughts, particularly since we saw the disturbing report, will give you more strength and courage.

We love and respect your parents; they are never very far from the ramparts, and they carry a lamp which throws up a strong and bright flame which tends to shine far beyond the family circle. Any danger or threat of danger to them immediately becomes a matter of real concern to us all. Please assure them that they enjoy our admiration and that we wish them good fortune and the best of luck. That is one reason why the cruel attack on the house disturbed us so much.

During the last ten years, and more particularly since 1979, there is virtually nothing I have not tried to contact your father, but all my efforts were in vain. If this brief note reaches you, he must know that this is the nearest I can come to him.

But this is your letter and I want to tell you that a few years back, I read an article under your name in the Sunday Express, I think, which I found interesting. I thought it then, as I still do, that you have something to say. I accordingly hoped that you would write regularly in that paper and I was disappointed when your articles did not appear.

There is a wide and eager audience for fresh ideas, from young people who can think correctly and express themselves well. This is why I still look forward to seeing your articles some day. Meantime, I send my fondest regards and best wishes to you, Zanelei & the baby; your sisters, Thandeka and Naomi and their husbands and, of course, to your parents.

Very sincerely,

Uncle Nelson

Mr Trevor Tutu, P.O. Box 31190, Braamfontein, 2017

PS. Any response to this note must be registered

[Another note in Afrikaans]

3. The recipient [Trevor Tutu] is being encouraged to go ahead with propaganda in the newspapers. And he [Mandela] is also encouraging and supporting Bishop Tutu’s action on various fronts

4. This letter must not be released

Commanding Officer

Commander of Pollsmoor Prison

Brigadier F C Munro

The first offer to release Mandela from prison came in 1974, on condition that he agreed to move to the region of his birth, the rural Transkei. His rejection of the proposal was not enough to kill the idea. Ten years later, his nephew Kaiser Matanzimai approached him with the same offer. Matanzima, known by his initials, KD, or by his initiation name, Daliwonga, had been with his freedom fighter relative at Fort Hare University. Mandela was angry to discover years later that Matanzima had involved himself in the apartheid regime’s ‘Bantustan’ programme whereby nominal independence was given to so-called African homelands. The apartheid regime aimed to rid South Africa of all black people and so created ten homelands set aside for the occupation of Africans, which were organised by ethnic group. Four of them – Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana, and Venda – were declared ‘independent states’ but were not recognised by other countries. Others had partial autonomy. The government carried out forced removals and literally dumped millions of people in these territories. They were generally poverty-stricken and provided few opportunities. Bophuthatstwana, for instance, consisted of scattered and separate pieces of land and one had to cross through South African territory to get from one part of it to the other.

Within months of Mandela’s refusal of Matanzima’s offer, South Africa’s president, P. W. Botha, used his State of the Nation Address at the opening of Parliament to suggest that all political prisoners would be freed on condition that they denounced violence as a method to achieving democracy. Mandela’s responses were withering in their rage. Both the letter written to Botha directly and a message written for a political rally, where it was read out by his daughter Zindzi,ii showed to the world a man who was not about to be manipulated.

Black South Africans were once more on the rise and virtually on a daily basis protests emerged from almost every corner of the country. The United Democratic Front, a huge umbrella body of anti-apartheid organisations, was unveiled in late 1983 and became the de facto internal ANC.

Botha’s declaration of a series of states of emergency from 1985 did not quell the anger of the people but increased their determination. South Africa was subject to martial law, leaving tens of thousands, including children, detained without trial, many for years. Each protest resulted in death at the barrel of the state’s weaponry. And every funeral resulted in further death.

The potent combination of the ANC in exile and the anti-apartheid movement in general had succeeded in bringing the inhumanity of apartheid into the world’s psyche. Economic and other sanctions were beginning to bite against the apartheid regime.

To Winnie Mandela,i his wife

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

27.12.84

Darling Mum,

[Sections of] the letter to Daliwonga,ii which I handed in this morning for dispatch to Umtata,iii were summarised in the front page of today’s Die Burgeriv with the following headline: Matanzima doen aanbod (Matanzima makes an offer) Mandela verwerp vrylating (Mandela rejects release). This is the letter.

“Ngubengcuka,v

Nobandlavi has informed me that you have pardoned my nephews,vii and I am grateful for the gesture. I am more particularly touched when I think of my sister’s feeling about the matter and I thank you once more for your kind consideration.

Nobandla also informs me that you have now been able to persuade the Government to release political prisoners, and that you have also consulted with the other “homeland” leaders who have given you their full support in the matter. It appears from what she tells me that you and the Government intend that I and some of my colleagues should be released to Umtata.

I perhaps need to remind you that when you first wanted to visit us in 1977 my colleagues and I decided that, because of your position in the implementation of the Bantustan system, we could not accede to your request.

Again in February this year when you wanted to come and discuss the question of our release, we reiterated our stand and your request was not acceded to. In particular, we pointed out that the idea of our release being linked to a Bantustan was totally and utterly unacceptable to us.

While we appreciate your concern over the incarceration of political prisoners, we must point our that your persistence in linking our release with the Bantustans, despite our strong and clearly expressed opposition to the scheme, is highly disturbing, if not provocative, and we urge you to not continue pursuing a course which will inevitably result in an unpleasant confrontation between you and ourselves.

We will, under no circumstances, accept being released to the Transkei or any other Bantustan. You know fully well that we have spent the better part of our lives in prison exactly because we are opposed to the very idea of separate development which makes us foreigners in our own country and which enables the Government to perpetuate our oppression up to this very day.

We accordingly request you to desist from this explosive plan and we sincerely hope that this is the last time we will ever be pestered with it.

Ozithobileyo,i

Dalibunga.”

Purely as a matter of courtesy, I would have preferred that the contents of the letter should be published only after Daliwonga had received it. But publication was made without our consent and even knowledge. I hope you will be able to make it on the 5th & 6th of next month. Our time was very short and we had so much to talk about.

About the Charman’s, I can see no objection whatsoever in you accepting an unconditional offer which will enable you to feed those hungry mouths around you. But as I said, you must consult very fully but quickly on the matter. You now need a nightwatchman to look after the house and the complex; a reliable watchman, and you should be able to sort out the matter with the church leaders there.

With regard to the forthcoming clinic I suggest that you also include Dr Rachid Saloojeeii from Lenasia. He is a good fellow and Aminaiii should be able to contact him on your behalf.

Thanks a lot for the visit, the nice things you said and for your love, darling Mum. Looking forward to seeing you soon. I LOVE YOU! Affectionately, Madiba.

Nkosk Nobandla Mandela, 802 Phathakahle, P.O. Brandfort.

To Ismail Meer,i friend and comrade

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

29.1.85

Dear Ismail,

I have missed you so much these 22 yrs that there are occasions when I even entertain the wild hope that one good morning I will be told that you are waiting for me in the consultation room downstairs.

As I watch the world ageing, scenes from our younger days in Kholvad Houseii & Umngeni Rdiii come back so vividly as if they occurred only the other day – plodding endlessly on our text books, travelling to & from Milner Park,iv indulging in a bit of agitation, now on opposite sides & now together, some fruitless polemic with Boolav & Essack,vi & kept going throughout those lean yrs by a litany of dreams & expectations, some of which have been realised, while the fulfilment of others still eludes us to this day.

Nevertheless, few people will deny that the harvest has merely been delayed but far from destroyed. It is out there on rich & well-watered fields, even though the actual task of gathering it has proved far more testing than we once thought. For the moment, however, all that I want to tell you is that I miss you & that thinking of you affords me a lot of pleasure, & makes life rich & pleasant even under these grim conditions.

But it is about that tragic 31 Octobervii that I want to talk to you. You will, of course, appreciate that my present position does not allow me to express my feelings & thoughts fully & freely as I would have liked. It is sufficient to say that when reports reach us that Indirabenviii had passed away, I had already exhausted my 1984 quota of outgoing letters. This is the only reason why it took me so long to respond.

Even though Zamiix may have already conveyed our condolences (please check) I would like Rajivi to know that he & family are in our thoughts in their bereavement, that on occasions of this nature it is appropriate to recall the immortal words which have been said over & over again: When you are alone, you are not alone, there is always a haven of friends nearby. For Rajiv now to feel all alone is but natural. But in actual fact he is not alone. We are his friends, we are close to him & we fully [Share] the deep sorrow that has hit the family.

Indira was a brick of pure gold & her death is a painful blow which [we] find difficult to endure. She lived up to expectations & measured remarkably well to the countless challenges which confronted her during the last 18 yrs.

[There] must be few world leaders who are so revered but who are lovingly [referred] to by their first name by thousands of South Africans as Indira. [People] from different walks of life seemed to have accepted her as one of [them] &, to them, she could have come from Cato Manor,ii Soweto,iii or District [Six].iv That explains why her death has been so shattering.

[I] had hoped that one day Zami and I would travel all the way to India to meet Indira in person. That hope became a resolution especially after 1979. Although the yrs keep on rolling away & old age is beginning to threaten, hope [never] fades & that journey remains one of my fondest dreams.

[We] wish Rajiv well in his new officev & we sincerely hope that his youth & good health, his training & the support of friends from far & wide will enable him to bear the heavy work load with the same strength & assurance as was displayed by his famous mother over the past 18yrs. Again, our sincerest sympathies to Rajiv, Soniavi & Maneka.vii

I must repeat that I miss you badly & I hope you are keeping well. I do look forward to seeing you some day. Until then our love & fondest regards to you, Fatima,viii the children & everybody. Please do tell me about Nokhukhanyaix & her children.

Very Sincerely,

Nelson

Mr Ismail Meer, 148 Burnwood Rd, Sydenham, 4091

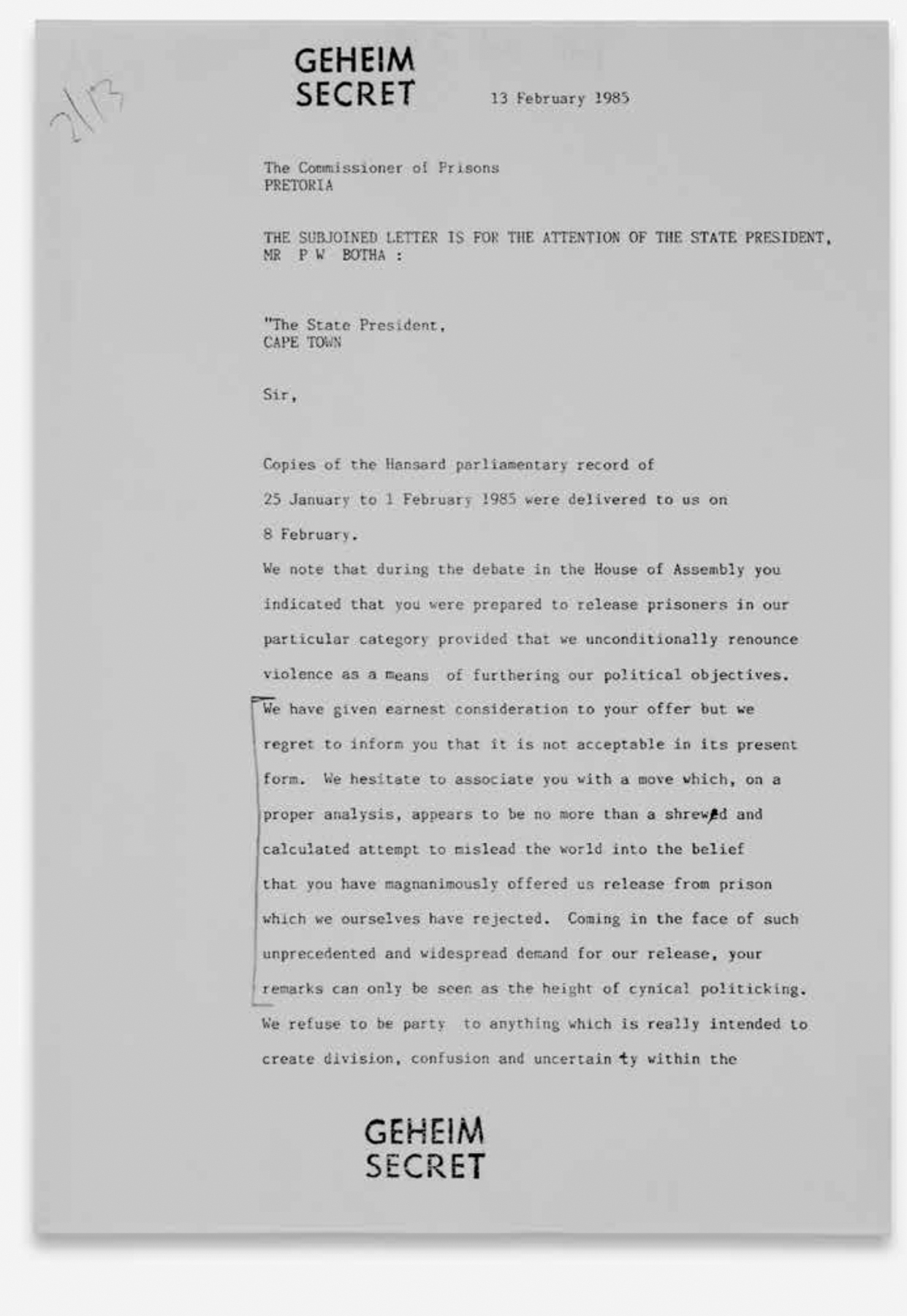

To P. W. Botha, president of South Africa

13 February 1985

The Commissioner of Prisons,

Pretoria.

The subjoined letter is for the attention of the State President,

Mr P. W. Botha :

“The State President,

Cape Town

Sir,

Copies of the Hansard parliamentary record to 25 January to 1 February were delivered to us on 8 February.

We note that during the debate in the House of Assembly you indicated that you were prepared to release prisoners in our particular category provided that we unconditionally renounce violence as a means of furthering our political objectives.

We have given earnest consideration to your offer but we regret to inform you that it is not acceptable in its present form. We hesitate to associate you with a move which, on a proper analysis, appears to be no more than a shrewd and calculated attempt to mislead the world into the belief that you have magnanimously offered us release from prison which we ourselves have rejected. Coming in the face of such unprecedented and widespread demand for our release, your remarks can only be seen as the height of cynical politicking.

We refuse to be party to anything which is really intended to create division, confusion and uncertainty within the African National Congress at a time when the unity of the organisation has become a matter of crucial importance to the whole country. The refusal by the Department of Prisons to allow us to consult fellow prisoners in other prisons has confirmed our view.

Just as some of us refused the humiliating condition that we should be released to the Transkei,i we also reject your offer on the same ground. No self-respecting human being will demean and humiliate himself by making a commitment of the nature you demand. You ought not to perpetuate our imprisonment by the simple expedient of setting conditions which, to your own knowledge, we will never under any circumstances accept.

Our political beliefs are largely influenced by the Freedom Charter,i a programme of principles whose basic premise is the equality of all human beings. It is not only the clearest repudiation of all forms of racial discrimination, but also the country’s most advanced statement of political principles. It calls for universal franchise in a united South Africa and for the equitable distribution of the wealth of the country.

The intensification of apartheid, the banning of political organisations and the closing of all channels of peaceful protest conflicted sharply with these principles and forced the ANC to turn to violence. Consequently, until apartheid is completely uprooted, our people will continue to kill one another and South Africa will be subjected to all the pressures of an escalating civil war.

Yet the ANC has for almost 50 years since its establishment faithfully followed peaceful and non-violent forms of struggle. During the period 1952 to 1961 aloneii it appealed, in vain, to no less than three South African premiers to call a round-table conference of all population groups where the country’s problems could be thrashed out, and it only resorted to violence when all other options had been blocked.

The peaceful and non-violent nature of our struggle never made any impression to your government. Innocent and defenceless people were pitilessly massacred in the course of peaceful demonstrations. You will remember the shootings in Johannesburg on 1 May 1950iii and in Sharpeville in 1960.iv On both occasions, as in every other instance of police brutality, the victims had invariably been unarmed and defenceless men, women and even children. At that time the ANC had not even mooted the idea of resorting to armed struggle. You were the country’s Defence Minister when no less than 600 people, mostly children, were shot down in Soweto in 1976. You were the country’s premier when the police beat up people, again in the course of orderly demonstrations against the 1984 coloured and Indian elections,i and 7000 heavily armed troopers invaded the Vaal Triangle to put down an essentially peaceful protest by the residents.ii

Apartheid, which is condemned not only by blacks but also by a substantial section of the whites, is the greatest single source of violence against our people. As leader of the National Party, which seeks to uphold apartheid through force and violence, we expect you to be the first to renounce violence.

But it would seem that you have no intention whatsoever of using democratic and peaceful forms of dealing with black grievances, that the real purpose of attaching conditions to your offer is to ensure that the NP should enjoy the monopoly of committing violence against defenceless people. The founding of Umkhonto weSizwe was designed to end that monopoly and forcefully bring home to the rulers that the oppressed people were prepared to stand up and defend themselves and to fight back if necessary, with force.

We note that on page 312 of Hansard you say that you are personally prepared to go a long way to relax the tensions in inter-group relations in this country but that you are not prepared to lead the whites to abdication. By making this statement you have again categorically reaffirmed that you remain obsessed with the preservation of domination by the white minority. You should not be surprised, therefore, if, in spite of the supposed good intentions of the government, the vast masses of the oppressed people continue to regard you as a mere broker of the interests of the white tribe, and consequently unfit to handle national affairs.

Again on pages 318–319 you state that you cannot talk with people who do not want to cooperate, that you hold talks with every possible leader who is prepared to renounce violence.

Coming from the leader of the NP this statement is a shocking revelation as it shows more than anything else, that there is not a single figure in that party today who is advanced enough to understand the basic problems of our country, who has profited from the bitter experiences of the 37 years of NP rule, and who is prepared to take a bold lead towards the building of a truly democratic South Africa.

It is clear from this statement that you would prefer to talk only to people who accept apartheid even though they are emphatically repudiated by the very community on whom you want to impose them, through violence, if necessary.

We would have thought that the ongoing and increasing resistance in black townships, despite the massive deployment of the Defence Force, would have brought home to you the utter futility of unacceptable apartheid structures, manned by servile and self-seeking individuals of dubious credentials. But your government seems bent on continuing to move along this costly path and, instead of heeding the voice of the true leaders of the communities, in many cases they have been flung into prison. If your government seriously wants to halt the escalating violence, the only method open is to declare your commitment to end the evil of apartheid, and show your willingness to negotiate with the true leaders at local and national levels.

At no time have the oppressed people, especially the youth, displayed such unity in action, such resistance to racial oppression and such prolonged demonstrations in the face of brutal military and police action. Students in secondary schools and the universities are clamouring for the end of apartheid now and for equal opportunities for all. Black and white churchmen and intellectuals, civic associations and workers’ and women’s organisations demand genuine political changes. Those who “co-operate” with you, who have served with you so loyally throughout these troubled years have not at all helped you to stem the rapidly rising tide. The coming confrontation will only be averted if the following steps are taken without delay.

1. The government must renounce violence first;

2. It must dismantle apartheid;

3. It must unban the ANC;

4. It must free all who have been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid;

5. It must guarantee free political activity.

On page 309 you refer to allegations which have regularly been made at the United Nations and throughout the world that Mr Mandela’s health has deteriorated in prison and that he is detained under inhuman conditions.

There is no need for you to be sanctimonious in this regard. The United Nations is an important and responsible organ of world peace and is, in many respects, the hope of the international community. Its affairs are handled by the finest brains on earth, by men whose integrity is flawless. If they made such allegations, they do so in the honest belief that they were true.

If we continue to enjoy good health, and if our spirits remain high it has not necessarily been due to any special consideration or care taken by the Department of Prisons. Indeed it is common knowledge that in the course of our long imprisonment, especially during the first years, the prison authorities had implemented a deliberate policy of doing everything to break our morale. We were subjected to harsh, if not brutal, treatment and permanent physical and spiritual harm was caused to many prisoners.

Although conditions have since improved in relation to the Sixties and Seventies, life in prison is not so rosy as you may suppose and we still face serious problems in many respects. There is still racial discrimination in our treatment; we have not yet won the right to be treated as political prisoners. We are no longer visited by the Minister of Prisons, the Commissioner of Prisons and other officials from the headquarters, and by judges and magistrates. These conditions are cause for concern to the United Nations, Organisation of African Unity,i Anti-apartheid Movementii and to our numerous friends.

Taking into account the actual practice of the Department of Prisons, we must reject the view that a life sentence means that one should die in prison. By applying to security prisoners the principle that “life is life” you are using double standards, since common law prisoners with clean prison records serve about 15 years of a life sentence. We must also remind you that it was the NP whose very first act on coming to power was to release the traitor Robey Leibrandtiii (and others) after he had served only a couple of years of his life sentence. These were men who had betrayed their own country to Nazi Germany during the last World War in which South Africa was involved.

As far as we are concerned we have long ago completed our life sentences. We’re now being actually kept in preventative detention without enjoying the rights attached to that category of prisoners. The outdated and universally rejected philosophy of retribution is being meted out to us, and every day we spend in prison is simply an act of revenge against us.

Despite your commitment to the maintenance of white supremacy, however, your attempt to create new apartheid structures, and your hostility to a non-racial system of government in this country, and despite our determination to resist this policy to the bitter end, the simple fact is that you are South Africa’s head of government, you enjoy the support of the majority of the white population and you can help change the course of South African history. A beginning can be made if you accept and agree to implement the five-point programme on pages 4–5 of this document. If you accept the programme our people would readily cooperate with you to sort out whatever problems arise as far as the implementation thereof is concerned.

In this regard, we have taken note of the fact that you no longer insist on some of us being released to the Transkei. We have also noted the restrained tone which you adopted when you made the offer in Parliament. We hope you will show the same flexibility and examine these proposals objectively. That flexibility and objectivity may help to create a better climate for a fruitful national debate.

Yours faithfully,

NELSON MANDELA

WALTER SISULU

RAYMOND MHLABA

AHMED KATHRADA

ANDREW MLANGENIi

[Each one signed above their name]

From time to time in the latter years of his imprisonment, Mandela received letters from people he had never met – ordinary members of the public who knew of him and wrote to show that he had support outside of his normal circle of friends and family. Mrs Ray Carter, a British-born nurse married to an Anglican bishop, John Carter, was one such supporter. This letter was provided by her family who said that she and Mandela had struck up a pen-pal relationship after she telephoned the head of Pollsmoor Prison saying she wanted to bring a birthday gift to Nelson Mandela. She promptly dropped off a paperback, called Daily Light, containing Biblical texts, two readings a day. Some months later a registered letter arrived from Mandela.

To Ray Carter, a supporter

4.3.85

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

Our dear Ray,

The picture on the outside cover of Daily Light has upset me beyond words. Although I spent no less than two decades on the Randi before I was arrested, I am still essentially a peasant in outlook. I am intrigued by the wilds, the bush, a blade of grass and by all the things which are associated with the veld.ii

Every time I look at the book – and I try to do so every morning and evening – I invariably start from the cover, and the mind immediately lights up. Long-forgotten scenes come back as fresh as dew. The thick bush, the ten fat sheep on a green field remind me of my childhood days in the countryside when everything I saw looked golden, a real place of bliss, an extension of heaven itself. That romantic world is engraved permanently in the memory and never fades, even though I now know as a fact that it is gone never to return.

Fourteen years after I had settled in Johannesburg I went back homeiii and reached my village in early evening. At sunrise I left the car behind and walked out into the veld in search of the world of my youth, but it was no more.

The bush, where I used to pick wild fruits, dig up edible roots and trap small game, was now an unimpressive grove of scattered and stunted shrubs. The river, in which I swam on hot days and caught fat eels, was choking in mud and sand. I could no longer see the blazing flowers that beautified the veld and sweetened the air.

Although the sweet rains had recently washed the area, and the rising sun was throwing its warmth over the entire veld, no honey bird or skylark greeted me. Overpopulation, overgrazing and soil erosion had done irreparable havoc, and everything seemed to be crumbling. Even the huge ironstones which had stood out defiantly for eternity appeared to be succumbing to the total desolation which enveloped the area. The cattle and sheep tended to be skinny and listless. Life itself seemed to be dying away slowly. This was the sad picture that confronted me on my return home almost 30 yrs ago. It contrasted very sharply with the place where I was born. I have never been home again, yet the romantic years of my youth remain printed clearly in the mind. The cover picture in Daily Light calls forth those wonderful times.

Where does this picture come from? It looks so familiar.

How long it has taken for a parcel or message from you to come through! It was some time in 1982, I think, that Zami (Winnie) asked whether I had received a postcard from you. My enquiries from the Commanding Officer drew a blank. You have to be a prisoner serving a life sentence to appreciate just how frustrating and painful it can be when the efforts of friends to reach and encourage you are blocked somewhere along the line.

But as I look back now, that frustration was not without value. You have turned it into triumph. Your determination to break through the barriers is a measure of the depth of your love and concern. The three-word inscription in the book makes it a precious possession indeed. I sincerely hope that Zami and I will prove to be worthy of that love and support. I look forward to seeing you and Johni one day. Meantime, I send you my love and best wishes.

Sincerely,

Nelson

Mrs Ray Carter, 51 Dalene Rd, Bramley, 2192

To Lionel Ngakane,i a friend and filmmaker

1.4.85

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

Dear Lionel,

The world we knew so well seems to be crumbling down very fast, and the men and women who once moved scores of people are disappearing from the scene just as quickly. Lutuli,ii Dadoo,iii Matthews,iv Kotane,v Harmel,vi Gomas, the Naickers,vii Marks,viii Molema,ix Letele,x Ruth First,xi Njongwe,xii Calata,xiii Ngoyi,xiv Peake,xv Hodgson,xvi Nokwexvii and many others now sleep in eternal peace; and all this happens in less than two decades.

We will never see them again, exchange views with them when problems arise, or exploit their immense influence in the struggle for the South Africa of our dreams. But few people will deny that in their lifetime they made a magnificent achievement and, in the process created a rich tradition which serves as a source of pride and strength to those who have now stepped into their shoes.

We were so busy outside prison that we hardly had time to think seriously about death. But you have to be locked up in a prison cell for life to appreciate the paralysing grief which seizes you when death strikes close to you. To lose a leading public figure can be a painful blow; but to lose a lifelong friend and neighbour is a devastating experience, and sharpens the sense of shock beyond words.

This is how I felt when Zamii gave me the sad news of the death of your beloved mother, adding that at that time your father was under detention and had to attend the funeral under police escort. I thought of you, Pascal,ii Lindi, Seleke, Mpho, Thaboiii and, of course, your father. I sent him a letter of condolence which I hope he also conveyed to you all.

The death of your father was equally devastating, and particularly so because I learnt about it from press reports as I was about to reply to his last letter which I had received on 31 December 1984. That shock unlocked a corner of my mind and I literally re-lived the almost 40 years of our friendship.

I particularly recalled an occasion at the Bantu Men’s Social Centreiv when we were addressed by Dr Yerganv towards the end of the Defiance Campaign.vi Attendance was by invitation only and the City’s top brass was all there – Xuma,vii Mosaka, Rathebe, Denelane, Madibane, Ntloana, Xorile, Twala, Rezant, Mali, Nobanda, Magagane, Mophiring and so on. The audience had been made specially receptive by the D.C.viii and Yergan, who gave an outstanding review of the national movements on our continent, was in terrific form. You could hear a pin drop. He closed that brilliant speech with a concerted attack on Communism – and drew prolonged ovation from that elitist audience.

There followed a chorus of praises for Yergan until your father took the floor. He could not match Yergan in eloquence and in the vast amount of scientific knowledge the American commanded. But he spoke in the simple language we all understood and drew attention to issues we deeply cherished. He made pertinent observations on Yergan’s deafening silence on our struggle generally and on the current D.C. in particular. Pressing his attack he challenged our guest speaker to speak about the giant American cartels, trusts and multi-national corporations that were causing so much misery and hardship throughout the world, and he foiled Yergan’s attempt to drag us into the cold war. The same people who had given the speaker such a prolonged ovation now applauded your father just as enthusiastically. I must confess that I was more than impressed.

During the 1960 state of emergency,i we spent several months with him in the Pretoria local prison. Again he showed special qualities of leadership and was of considerable help in the maintenance of morale and discipline. There are many aspects of his life that flashed across the mind on that unforgettable day when I learnt of his death. But a restricted prison letter is not a suitable channel to express my views frankly and fully on such matters. It is sufficient for me to say that Zami and I will always treasure the memory of our friendship with your parents. Please convey these sentiments to Pascal, Lindi, Seleke, Mpho and Thabo. The attached cutting from the Sowetan is hopelessly inadequate and inaccurate and I sincerely hope that you or Lindi will in due course record the story of his life and make it available to a wider audience. That is a challenge to you all, but especially to Lindi,ii who has special qualifications, both academically and from her actual role in the struggle, to undertake such an important task.

Turning now to more lighter matters, I must confess that I am keen to hear more about your personal affairs. I know a direct question will not ruffle you. Are you married? If so, who is the fortunate young lady? How strong is your manpower? I must add that I never forget the day we spent together in London, and it pleased me tremendously to know that around O.R.iii there were talented young men of your calibre. You may not be aware that that discovery made me even more attached to your parents.

Pascal and I spent a lot of time together at home, and when I visited Durban in 1955 I made a special point to see him. But it was the three years that we spent together somewhere that made an even greater mark on me. I have not heard of him for some time now and would like to have his address. It was a pleasant surprise to me to learn that Cliffordiv is now Lesotho’s ambassador in Rome.v Until I saw press reports to that effect, I had been under the impression that he was a UNO. I will be quite happy if these reports are correct. I have a lot of admiration for Chief Leabua and, from this distance, he seems to be playing the trump cards exceptionally well.

Selekei was a mere teenager when I last saw her, but I was later told that she was happily married to a medical practitioner in Maseru. I look forward to seeing all of you some day. Meantime I send you my fondest regards and best wishes.

Sincerely,

Madiba

Mr Lionel Ngakane, c/o Mr Paul Joseph, London

P.S. If you find time to reply to this note, please register your letter.

To Sheena Duncan,ii president of Black Sash

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

1.4.85

Dear Mrs Duncan,

In my current position it is by no means easy to keep abreast of the course of events outside prison. It may well be that the membership of the B-Sash has not grown significantly over the last 30 years and that, in this respect, this pattern of development is not likely to be different in the immediate future at least.

But few people will deny that, in spite of its relatively small numbers, the impact of the Sash is quite formidable, and that it has emerged as one of the forces which help to focus attention on those social issues which are shattering the lives of so many people. It is giving a bold lead on how these problems can be concretely tackled and, in this way, it helps to bring a measure of relief and hope to many victims of a degrading social order.

The ideals we cherish, our fondest dreams and fervent hopes may not be realised in our lifetime. But that is besides the point. The knowledge that in your day you did your duty, and lived up to the expectations of your fellowmen is in itself a rewarding experience and magnificent achievement. The good image which the Sash is projecting may be largely due to the wider realisation that it is fulfilling these expectations.

To speak with a firm and clear voice on major national questions, unprotected by the shield of immunity enjoyed by members of the country’s organs of government, and unruffled by the countless repurcussions of being ostracised by a privileged minority, is a measure of your deep concern for human rights and commitment to the principle of justice for all. In this regard, your recent comments in Port Elizabeth,i articulating as they did, the convictions of those who strive for real progress and a new South Africa were indeed significant.

In spite of the immense difficulties against which you have to operate, your voice is heard right across the country. Even though [it is] frowned upon by some, it pricks the conscience of others and is warmly welcomed by all good men and women. Those who are prepared to face problems at eyeball range, and who embrace universal beliefs which have changed the course of history in many societies must, in due course, command solid support and admiration far beyond their own ranks.

In congratulating you on your 30th birthday,ii I must add that I fully share the view that you “can look back with pride on three decades of endeavour which now, at least, is beginning to bear fruit.”

In conclusion, I must point out that I know so many of your colleagues that if I were to name each and every one in this letter, the list would be too long. All I can do is to assure you of my fondest regards and best wishes.

Sincerely,

[Signed NRMandela]

These two letters to anti-apartheid activist and lawyer Archie Gumede demonstrate the difficulties and frustrations with writing and receiving letters in prison and the lack of information about what happened to the letters.

Suspecting that the letter he wrote to Gumede in 1975 never reached him, Mandela rewrites it, from the copy he jotted down at the time, and resends it to him nearly ten years later.

To Archie Gumede,i comrade & friend

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

8.7.85

Phakathwayo! Qwabe!ii

The other day I was going through the notebook in which I keep the record of my outgoing letters, and I came across the copy of the attached letter, which I wrote to you on Jan 1, 1975.iii As you have never responded, and in view of the peculiar problems we were experiencing with our post at the time, I have assumed that it never reached you.

Although more than 10 years have passed since it was written, and although some of its contents are now hopelessly outdated I, nonetheless, thought you should get it. The letter was written when Mphephethe,iv Sibalukhulu, Danapathyv and Georgina’s husband from Hammarsdale were all with you over therevi and fairly active. One of the aims of the letter was to make them aware that there was deep appreciation for their work.

You will also bear in mind that, at that time, the relations between Khongolosevii and Shengeviii were good, and there was cooperation in many areas. In addition, he and I had been in contact since the late 60’s, and he still sends me goodwill messages on specific occasions. On the Island we fully discussed the matter in a special meeting of reps from all sections, and it was felt that it would be a mistake to ignore his gestures. I accordingly continued to respond.

Last year he sent me another telegram on a personal matter and my colleagues and I exchanged views. Again it was felt that, subject to what you might advise, I should write and thank him. But by the time the note reached the family you could no longer be reached. The note was ultimately forwarded to him.

At this stage I would like to digress a bit and tell you about a young lady, Ms Nomsa Khanyeza, 3156, Nkwaz Rd, Imbali, whose letter I received in Nov ’82 and to which I immediately replied. I never heard from her again. I would like you to visit her home when you are in the area. In particular I would like to know whether she is still at school, and whether her parents have the funds for her education. From her letter she appears to be a child of ability.

Perhaps Thozamile and Sisa are aware that Between the Lines: Conversations in SAi by Harriet Sergeant has been published. She has some interesting observations to make on a wide variety of interviews. But a young lady of 26 can often be outspoken, and she seems to have recorded intimate sentiments and reactions which were not meant for public consumption. Although she is forthright in her manner, in my opinion, she has said nothing really damaging about the trade unionists she met. I am keen to know who Connaugh is. This is apparently the cover name of the bearded white man with jeans, earphones on his head, microphone in hand and a recording machine at the ELii trade union meeting. Please get me this information if they already have the book.

In conclusion, I would like to draw your attention to a letter in a JHBiii daily which dealt with the case of 9 men who were condemned to death by Queen Victoria for treason. As a result of protests from all over the world the men were banished. Many years thereafter, the Queen learned that one of these men had been elected PMiv of Australia,v the second was appointed Brigadier-General in the U.S.A. Army,vi the third became Attorney-General for Australia,vii the fourth succeeded the third as A.G.,viii the fifth became Minister of Agriculture for Canada,ix the sixth also became Brigadier-General in the U.S.A.,x the seventh was appointed Governor-General of Montana,xi the eighth became a prominent New York politician,xii and the last was appointed Governor-General of Newfoundland.xiii

It is a relevant story which, although you are probably aware of it, I think it proper to remind you of it. Fondest regards and best wishes to you and all your colleagues. Remember that you are all in our thoughts.

Sincerely, Madiba.

P.S. Nomsa was at the time of writing the letter a pupil at the Georgetown High School.

[The attached letter]

To Archie Gumede,i friend and comrade

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

P/B X4, TOKAI, 7966

January 1, 1975 [resent on 7 July 1985]

Phakathwayo Qwabe!ii

I have been thinking of writing to you since the death of A.J.iii You were so close to him that, though I immediately wrote to the Old Lady,iv I felt I should also send my condolences to you, M.B.,v Zanu [or Zami],vi Sibalukhulu and Siphithiphithi. You have been together for a long time, handled important problems jointly, and moved forward in tight formation as Nodunehlezi did many years ago. It is difficult to think of the chief without at the same time thinking of the five of you.

I still well remember the Drill Hallvii when you would come together almost instinctively, talk about soil and sand and, at times, relax over a dish of amadumbe,viii punctuating the conversation with repeated “ha-a-a-wu! ha- a-a-a-wu!”ix

In due course you were admitted as an attorney and only now do I write to say: well done! People who hardly hear from us may be those we trust and respect most. We may keep quiet because we are certain that they will understand that pressure of other commitments makes it difficult to reach them.

I have thought of you often these twelve years, equally felt the grimness that gripped you, especially in ’63,i and rejoiced with you when the sun shone again. I was at Mgungundlovuii in March ’61iii and have been wondering whether I actually met you on that occasion. I stayed with Mandla’s parents. In ’55 I had spent a whole night at Boom St.iv chatting with Moses,v Chota,vi Omarvii and others. The next day Mungalviii and I travelled to Groutvilleix where I spent a whole day with AJ. By the way, I was returning from him in Aug ’62 when I met your homeboys in Howick.x

I also think a lot about Mphephethe, Sibalukhulu, Georgina’s hubby, MB, RM and Mutwana wa kwa Phindangene with fond memories. When New Agexi was strong enough to do her weekly rounds, Mphephethe had a powerful horse he could ride to reach us all, and we knew what he thought. Old and famous horses keel over like many that went before, some to be forgotten forever and others to be remembered as mere objects of history, and of interest to academicians only. But the disappearance of this one has left a void that will be felt alike by stable owners, jockeys, punters and the public at large.xii There still will be many race meetings here, but for some time we will miss the tension and sharpness of competition which NAxiii brought into every such race.

In his short stories Mphephethe always had something new and meaningful to say, and his theme, style and simplicity always absorbed me. I hope that with age and all the experience of eight full years away from Mgungundlovu, he has returned in earnest to his parchment and quill, more prepared than ever before.

About two years ago I had the pleasure of reading a thesis he had prepared. I would have liked to discuss some aspects discreetly with him, and one of my regrets is that this opportunity never came. The feeling of regret is all the more painful because his handling of the theoretical issues made a powerful impact on me. Thereafter I read another essay by him on more topical isses, and I was very happy to learn that our thoughts were substantially similar. I hope he keeps fit by now and again donning ibhetshu,i letting every one of his bones swing to the beat of the ox-hide drum and indlamu.ii

I have met Sibalukhulu far more often than Mphephethe. We have been together several times in Durban and for a stretch in J.H.B.iii I last had a chat with him in Aug ’62. He will remember the occasion very well. Milner, Selbourne, MB, Mduduzi and Elias were there. The uncompromising champion of Impabanga was, as usual, neat in dress and his hair was cola black and glossy. Little did I suspect that it was as white as mine, and that Sibalukhulu kept it fresh with Nugget. On that occasion, he revealed surprising flexibility as we chatted along, and I came away feeling much closer than I have ever been to him. This is the impression of him that I have carried during the last 12 years; that is why I miss him so much and really look forward to seeing him one day.

Time was when Georgina’s hubby, Danapathy and I were like triplets, and I am still inclined to feel somewhat lonely when I think of the immense mileage that separates us. But it is the fact of being triplets that still dominates my thoughts and feelings.

Many threads bind us together. Centuries ago your forefathers and mine scratched the fertile valleys of the Tukelaiv for a living and drank from its sweet waters. Mafukuzela,v Lentanka,vi Rubusanavii and others were there in 1912 to extend and deepen those ties, a development with which your Pa’s name is closely associated.

You have added yet another thread, and we belong to that tribe which exploits advocates, magistrates and judges. Again, well done Mnguni. I am looking forward to seeing your family some day, as well as Sukthi, Sha, Sahdhamviii and their mum.

Fatimai has already been here and we maintain regular contact. Alzena, Tryfina, Mabhala, Magoba and Gladys have sent Xmas cards every year since ’64 and, in the last three years or so they have been joined by Sukthi and family. All these are ladies who love and friendship I highly value and will ask you to give them my fondest regards. Some day I may be able to shake their hands very warmly.

Once again, my deepest sympathy to you, MB, Zanu [or Zami], Sibalukhulu and Phithiphithi.

Sincerely,

Nel

Mr Archie Gumede, 30 Moodie St, Pinetown [3600]

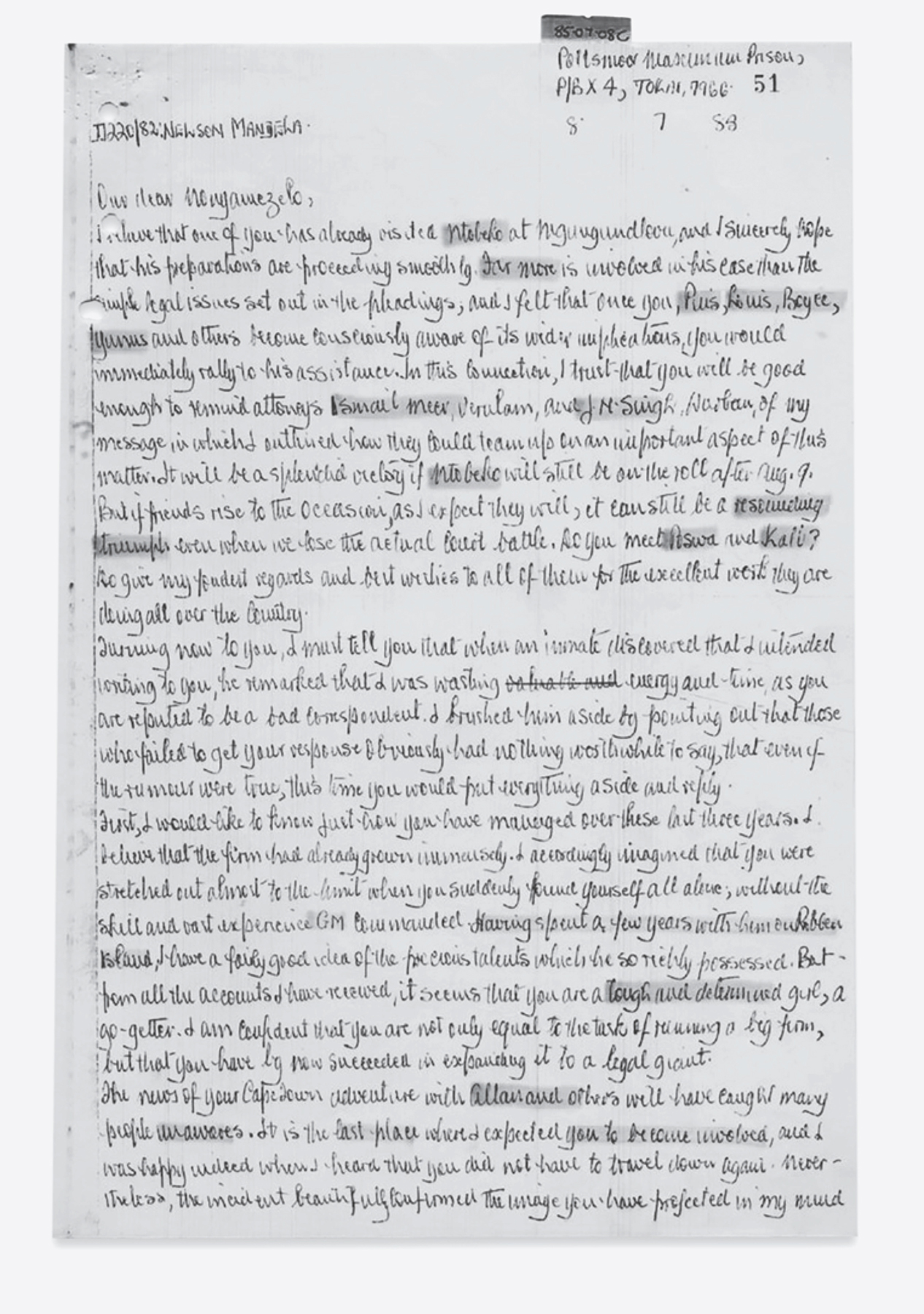

To Victoria Nonyamezelo Mxenge,ii lawyer and political activist

8.7.85

8.7.85D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

Our dear Nonyamezelo,

I believe that one of you has already visited Ntobeko at Mgungundlovu,iii and I sincerely hope that his preparations are proceeding smoothly. Far more is involved in his case than the simple legal issues set out in the pleadings, and I felt that once you, Pius,iv Louis, Boyce, Yunus and others become consciously aware of its wider implications, you would immediately rally to his assistance. In this connection, I trust that you will be good enough to remind attorneys Ismail Meer, Verulam,i and JN Singh, Durban, of my message in which I outlined how they could team up on an important aspect of this matter. It will be a splendid victory if Ntobeko will still be on the roll after Aug 9. But if friends rise to the occasion, as I expect they will, it can still be a resounding triumph even when we lose the actual court battle. Do you meet Poswaii and Kall? Do give my fondest regards and best wishes to all of them for the excellent work they are doing all over the country.

Turning now to you, I must tell you that when an inmate discovered that I intended writing to you, he remarked that I was wasting energy and time, as you are reputed to be a bad correspondent, I brushed him aside by pointing out that those who failed to get your response obviously had nothing worthwhile to say, that even if the rumour were true, this time you would put everything aside and reply.

First, I would like to know just how you have managed over these last three years. I believe that the firm had already grown immensely. I accordingly imagined that you were stretched out almost to the limit when you suddenly found yourself all alone; without the skill and vast experience GMiii commanded. Having spent a few years with him on Robben Island, I have a fairly good idea of the precious talents which he so richly possessed. But – from all the accounts I have received, it seems that you are a tough and determined girl, a go-getter. I am confident that you are not only equal to the task of running a big firm, but that you have by now succeeded in expanding it to a legal giant.

The news of your Cape Town adventure with Allan and others will have caught many people unawares. It is the last place where I expected you to become involved, and I was happy indeed when I heard that you did not have to travel down again. Nevertheless, the incident beautifully confirmed the image you have projected in my mind all these years.

Are the children well, and how are they faring with their school work? Where and when did you spend your last holiday? An overseas vacation, if you have a passport, would certainly be a refreshing experience both from the point of view of your own health, and that of the firm. The batteries that keep you going require to be constantly charged and recharged, if you are going to maintain a high standard of performance on professional and wider issues. It would also be an unforgettable experience for you to visit some of the big USA legal firms, some of which have not less than 100 partners each, with computers and well-stocked libraries. Do consider that.

I notice that we now have several lawyers’ organisations: Lawyers for Human Rights,i Black Lawyers Associationii and the Democratic Lawyers Association.iii To which do you belong? Can you give me some information on the DLA?iv

Now I would like you to put a few telephone calls on my behalf to some friends over there: my sympathy to Chief Lutuli’sv son, Sibusiso, and his wife, Wilhelmina, who were attacked at their Gledhow store recently. We wish them a speedy and complete recovery. Last year I wrote to the Old lady, Nokhukhanya;vi I don’t know whether she ever received the letter as she never responded. Fondest regards to Diliza Mji, Senior,vii whose impressive contribution in the late 40s and early 50s can never be forgotten. The same sentiments to Diliza Mji, Juniorviii in regard to his current efforts. We are particularly proud of him, Assure attorney Vahed that although I have not seen him for 30 yrs, I think of him and his wife. To Billy Nairix just say, “Madiba sends warmest greetings to Thambi and Elsie” and to attorney Bhengu I say “Halala Dlabazana!”x

In conclusion I want to tell you that Zamixi and I love you, and we often talk about you when she visits me. We sincerely look forward to seeing you one day. Hope and the future are always before us, mainly because S.A. has produced many men and women of your calibre, who will never allow the flames to die down. Our love and best wishes to you and the children.

Kindly register your reply.

Sincerely, ‘Madiba’

Mrs Nonyamezelo Victoria Mxenge, 503 Damjee Centre, 158 Victoria St, Durban, 4001

To Nolinda Mgabela

D220/82: NELSON MANDELA

8.7.85

My dear Nolinda,

Your letter and beautiful photograph, for which I thank you, came when I was thinking of writing to Nongaye. Early last year, I wrote to Khayalethu enquiring, amongst others, about the funeral of your late Mum, your father’s health, and about a few friends. I received no reply from him, and I was quite surprised because I have never heard of a coward in Khwalo’s family. I still want that information and, if he cannot send it to me, then I am confident that you or Nongaye will gladly do so.

With regard to your schooling, I suggest that you immediately apply to a boarding school, like Lovedalei or Clarkebury,ii where you can continue your studies with less interference. For this purpose, I suggest that you approach some influential person, such as Dr Gilimamba Mahlati,iii to help you with the application for admission.

As far as your school fees and pocket money are concerned, I want you to write without delay, to Dr Beyers Naude, Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, P.O. Box 31190, Braamfontein, 2017. Tell him that you had written to me and that I would like them to help you with your matric and university fees.

Your letter should state that your mother, who was detained several times, died last year shortly after your father, Malcomess Mgabela, had returned after serving 18 years on Robben Island for a political offence. Because of his long imprisonment, and present harassment, he has been unable to save funds for the education of the children. At his age and with his views, it is almost impossible for him to get employment. It is for these reasons that you have no other way but to ask the SACCiv for help. You must indicate the standard you are doing at present and the school in which you are a pupil. Let Khayalethu and Nongaye help you in writing the letter and make sure that you include all the points mentioned above.

How is Mkhozi Khwalo? I sincerely hope that he is back home and that his blood pressure is under control. Give him my best regards.

Once more I would like you to know that I am grateful to you for your lovely letter and beautiful photo. I hope to hear from you again. From the photo you appear to be an attractive young lady, and I suspect that the boys are going to worry you. What is important, at the present moment, is your education. It would be advisable for you not to have any serious affair until you complete your legal studies.

Meantime, I send my love and fondest regards to you, Nongaye, Khayaletu, Nosizwe and Ntomboyise.

Sincerely,

Tatai

Miss Nolinda Mgabela, 8235, Mdantsane, 5219

Do register all your letters to me, as well as that to Dr Naude

Nelson Mandela’s health became the subject of widespread public discussion and concern in late 1985 when it became known that he had been admitted to a Cape Town hospital for prostate surgery.

During the preceding twenty years he had been admitted to hospital for minor and short procedures, but this was different. He was sixty-seven years old and the idea that he could die in prison was as alarming to the regime as to his family and supporters.

He was admitted to the Volks Hospital in a leafy suburb close to the city centre on Sunday 3 November. He and his family had assembled an impressive array of trusted medical practitioners to watch over him and the procedure.

Significantly, he had ‘a surprising and unexpected visitor,59 the then minister of justice, Kobie Coetsee. Although Mandela had written to Coetsee asking for a meeting to discuss potential talks between the government and the ANC, he had not expected to see him in the hospital. Their first conversation was confined to pleasantries but Mandela did broach the subject of his wife whose home of banishment in Brandfort had been firebombed when she was away in Johannesburg for medical treatment. The house was repaired and the police were making attempts to have her return there, to a dangerous situation. He asked Coetsee to allow her to remain in Johannesburg.60

Coetsee became a crucial connection in talks Mandela began with a government team the following year. These exploratory talks were planned to investigate whether the government could enter into formal negotiations with the ANC about the end of white minority rule.

The meeting with Coetsee could also have been the catalyst for his separation from his comrades when he returned to Pollsmoor on 23 November. From that time, they had to make official requests to see each other after having spent almost every day of the last almost twenty-two years together. Mandela suspected that it was so that the meetings with government could begin.61 Finally, in May 1986, he began what became a long series of meetings with Coetsee and other government officials – the precursor to eventually full-blown talks between the apartheid regime and the ANC after his release from prison in 1990.

To the University of South Africa

Student no. 240-094-4

15.10.85

The Registrar (Academic),

University of South Africa,

PO Box 392, Pretoria 0001

Dear Sir,

I am compelled to request you to allow me to write the October/November examinations in five subjects in January 1986.

I had intended having an operationi immediately after I had written the examinations. But I was advised on medical grounds to do so without further delay, an advice which I accepted.

As a general rule, and probably for security reasons, the Department of Prisons does not advise a prisoner of the actual date when an operation will be made. But on 29 September, and after consultation with the medical team which will conduct the operation, it was indicated that this would be done during the week commencing on 7 October. I then suspended my preparations for the examinations in the hope that I would apply for a special aegrotat in due course.

Later I was informed that the operation had been postponed to the end of this month or beginning of November. I then resumed preparations for the examinations but I was, at the same time, subjected to a series of medical tests and consultations which affected my concentration and disrupted my preparations. [For] these reasons, I must request you to permit me to write the examinations next January.