2

Chicago in Depth

The Chicago River has played a major role in the history of the city.

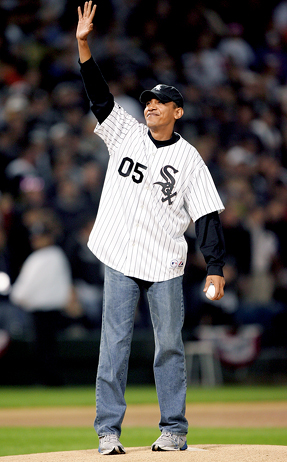

Chicago has spent the last few years in the national media spotlight, for reasons both inspiring and embarrassing. On the one hand, it’s the adopted hometown of President Barack Obama, the place he got his start in politics and where he still maintains his Hyde Park home. His victory rally in downtown’s Grant Park signaled Chicago’s vitality and influence to the whole world (many of his top presidential advisors were local business and philanthropic leaders before they moved to Washington).

Unfortunately, Chicago must also lay claim to politicians such as former Illinois state governor Rod Blagojevich. “Blago,” a product of the city’s shady Democratic political machine, stunned even cynical Chicagoans with his blatant moneygrubbing and attempts to sell Obama’s former Senate seat to the highest bidder. Obama’s talk about a new era of hope in politics turned out to be short-lived, with his ties to Chicago wheeler-dealers a liability. Blagojevich proved that the old ways of doing business aren’t so easily erased.

It’s easy to be cynical about Chicago politics—the miracle is that such cynicism doesn’t pervade the way Chicagoans feel about their city. We’re proud of our gorgeous skyline and love nothing better than hearing visitors compare our hometown favorably to New York. (You’ll make friends for life if you tell us you’d rather live here than the Big Apple.) As the retail, financial, and legal center of the Midwest, Chicago has a thriving, diverse business community and an active arts scene, attracting everyone from thrifty wannabe hipsters to ambitious future CEOs. The one thing they’ve got in common? A certain humility that comes with living in the Second City. Being down-to-earth is a highly rated local virtue.

President Obama tossing the first pitch at a Cubs game.

In this chapter, you’ll get an overview of the issues facing the city today, as well as a quick primer on Chicago’s history. Because architecture plays such an important role in the look of the city—and so many influential architects have worked here—you’ll also find a guide to the major styles of buildings you’ll pass by during your visit. But you won’t get a full sense of the city’s spirit unless you understand the city’s role in popular culture, too. Chicago has been home to many great writers and has served as a setting for dozens of films, so this chapter includes a section on recommended books and movies. Check out a few before your trip to put you in a Chicago state of mind.

Chicago Today

Like other major American cities, Chicago has benefited from a renewed interest in urban living over the past 2 decades, as former suburbanites flock to luxury high-rise condos downtown. Where the Loop used to shut down after dark and on weekends, it’s now buzzing all week long, with a busy theater district and lively restaurants. Massive new condo buildings have sprung up along the lakefront south of the Loop, while the West Loop—once a no-man’s-land of industrial buildings—has become another hot residential neighborhood.

In many ways, this building boom has erased the physical legacy of Chicago’s past. The stockyards that built the city’s fortune have disappeared; the industrial factories that pumped smoke into the sky south of the city now sit vacant. While no one misses the stench of the stockyards or the pollution that came with being an industrial center, the city’s character has become muted along the way. Living here no longer requires the toughness that was once a hallmark of the native Chicagoan.

And yet a certain brashness remains. While some people may still have a “Second City” chip on their shoulders, we’ve gotten more confident about our ability to compete with New York or Los Angeles. We know our museums, restaurants, and entertainment options are as good as any other city’s in the country; we just wish everyone else knew it, too.

Relatively affordable compared to New York, Chicago is a popular post-college destination for ambitious young people from throughout the Midwest. The city also draws immigrants from other countries (as it has for more than 100 years). Hispanics (mostly of Mexican origin) now make up about one-third of the city’s population. Immigration from Eastern Europe is also common, especially from countries such as Poland, Russia, and Romania. This constant influx of new blood keeps the city vibrant.

This is not to say the city doesn’t have problems. With roughly 2.8 million people total, Chicago has nearly equal numbers of black and white residents—a rarity among today’s urban areas—but the residential districts continue to be some of the most segregated in the country. The South Side is overwhelmingly black; the North Side remains mostly white. As in other major cities, the public school system seems to constantly teeter on the edge of disaster. While fine schools are scattered throughout the city, many families are forced to send their children to substandard local schools with high dropout rates.

However, the waves of gentrification sweeping the city have transformed many neighborhoods for the better. For years, the city’s public housing was a particular disgrace, epitomized by decrepit 1960s high-rises that had degenerated into isolated bastions of violence and hopelessness. The largest and worst complexes have been torn down during the last decade, replaced with low-rise, mixed-income housing. Some streets I used to avoid after dark are now lined with brand-new supermarkets, parks, and—inevitably—a Starbucks or two.

The city’s crime problem has been more intractable. Despite a murder rate that’s one of the highest in the country, Chicago doesn’t strike visitors as a dangerous place, because most of the violence is contained within neighborhoods where gangs congregate and tourists rarely go. But gang-instigated shootings are still shockingly common on the South Side, and children are often innocent victims caught in the crossfire. It’s something we’ve gotten far too blasé about, and it continues to be a blot on Chicago’s reputation.

Another continuing embarrassment is our local politics. Time and again, our aldermen and other city officials reward our cynicism with yet another scandal involving insider payoffs and corrupt city contracts. For more than 20 years under Mayor Richard M. Daley (himself the son of another longtime mayor, Richard J. Daley), Chicagoans accepted a certain level of shady behavior—after all, there was no denying that the city blossomed under the Daleys’ leadership.

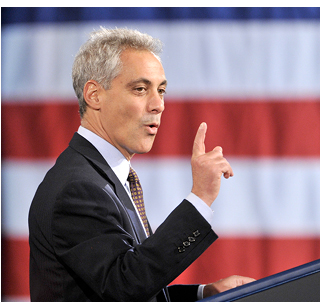

When the younger Daley stepped aside in the spring of 2011, his potential successors were quick to serve up the usual campaign promises about wiping out corruption. Now we’re left wondering: Is it possible? Our newest mayor, Rahm Emanuel, is no stranger to political fights: He worked in the Clinton White House, served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, and survived 2 years as President Obama’s chief of staff. It will be interesting to see how his take-no-prisoners style goes down with the complacent, business-as-usual Chicago City Council. Another test of his leadership will come as he attempts to reform the city’s struggling public-school system. Emanuel, a dance- and theater-lover, has also pledged his strong support to the city’s sometimes cash-strapped cultural institutions, which is good news for residents and visitors alike. In spite of the local politicians, we Chicagoans passionately defend and boast about our city. Ever since the stockyards were our main source of wealth, we’ve become masters of overlooking the unsavory. As long as Chicago thrives, we don’t seem to really care how it happens

Rahm Emanuel, Chicago’s mayor.

.

Looking Back: Chicago History

First Settlement

Chicago owes its existence to its strategic position: The patch of land where it stands straddles a key point along an inland water route linking Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1673, Jacques Marquette, a French Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet, an explorer, found a short portage between two critically placed rivers, one connected to the Mississippi, and the other (via the Chicago River) to Lake Michigan. Although Native Americans had blazed this trail centuries beforehand, its discovery by the French was the first step in Chicago’s founding—although no permanent settlement was built there for another 100 years.

By then, the British controlled the territory, having defeated the French over 70 years of intermittent warfare. After the Revolutionary War, the land around the mouth of the Chicago River passed to the United States. The Native American inhabitants, however, wouldn’t give up their land without a fight, which is why the first building erected here—between 1803 and 1808—was the military outpost Fort Dearborn. (It sat on the south side of what is now the Michigan Avenue Bridge, on the site of the current McCormick Tribune Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum.) Skirmishes with local Native American tribes continued until 1832. A year later, the settlement of 300-plus inhabitants was officially incorporated under the name “Chicago.” (A French version of a Native American word believed to mean “wild onion,” it may also have referred to the equally non-aromatic local skunks.)

Gateway to the West

Land speculation began immediately, and Chicago was carved piecemeal and sold off to finance the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which eliminated the narrow land portage and fulfilled the long-standing vision of connecting the two great waterways. Commercial activity quickly followed. Chicago grew in size and wealth, shipping grain and livestock to the Eastern markets and lumber to the prairies of the West. Ironically, by the time the Illinois and Michigan Canal was completed in 1848, the railroad had arrived, and the water route that gave Chicago its raison d’être was rapidly becoming obsolete. Boxcars, not boats, became the principal mode of transportation throughout the region. The combination of the railroad, the emergence of local manufacturing, and, later, the Civil War, caused Chicago to grow wildly.

The most revolutionary product of the era sprang from the mind of Chicago inventor Cyrus McCormick, whose reaper filled in for the farmhands who had been sent off to the nation’s battlefields. Local merchants not only thrived on the contraband trade in cotton during the war, but also secured lucrative contracts from the federal government to provide the army with tents, uniforms, saddles, harnesses, lumber, bread, and meat. By 1870, Chicago’s population had grown to 300,000, a thousand times greater than its original population, in just 37 years since incorporation.

The Great Fire

A year later, the city lay in ashes. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 began on the southwest side of the city on October 8. Legend places its exact origin in the O’Leary shed on DeKoven Street, although most historians have exonerated the poor cow that supposedly started the blaze by kicking over a lantern. The fire jumped the river and continued north through the night and the following day, fizzling out only when it started to rain. The fire took 300 lives—a relatively low number, considering its size—but destroyed 18,000 buildings and left 90,000 people homeless.

The city began to rebuild as soon as the rubble was cleared. By 1873, the city’s downtown business and financial district was up and running again, and 2 decades later Chicago had sufficiently recovered to stage the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition commemorating the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America. The Exposition was, in effect, Chicago’s grand coming-out party, a chance to show millions of visitors that this was a modern, progressive city. Chicago already had a reputation as a brash business center; now it proved it could also be beautiful. Harper’s Magazine described the “White City,” the collection of formal buildings constructed for the Exposition, as “a Venus that arose from Lake Michigan.”

The Great Fire gave an unprecedented boost to the professional and artistic development of the nation’s architects. Drawn by the unlimited opportunities to build, they gravitated to the city in droves, and the city raised a homegrown crop of architects. Chicago’s reputation as an American Athens, packed with monumental and decorative buildings, is a direct byproduct of the disastrous fire that nearly brought the city to ruin.

In the meantime, the city’s labor pool continued to grow, as many immigrants decided to stay rather than head for the prairie. Chicago still shipped meat and agricultural commodities around the nation and the world, and the city was rapidly becoming a mighty industrial center, creating finished goods, particularly for the markets of the ever-expanding Western settlements.

An artist’s rendering of the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire.

The Cradle of Organized Labor

Chicago never seemed to outgrow its frontier rawness. Greed, profiteering, exploitation, and corruption were as critical to its growth as hard work, ingenuity, and civic pride. The spirit of reform arose most powerfully from the working classes, people whose lives were plagued by poverty and disease despite the city’s prosperity. When the labor movement awoke in Chicago, it did so with a militancy and commitment that would inspire unions throughout the nation.

The fear and mistrust between workers and the local captains of industry came to a head during the Haymarket Riot in 1886. On May 1, tens of thousands of workers went on strike to demand an 8-hour workday. (Eventually, that date would be immortalized as a national workers’ holiday around the world—although never, ironically, in the United States.) A few days later, toward the end of a rally held by a group of anarchist labor activists in Haymarket Square, a bomb exploded near the line of policemen standing guard. The police fired into the crowd, and seven policemen and four workers were killed.

Although the 5-minute incident was in no sense a riot, it seemed to justify fears about the radicalism of the labor movement, and eight rally leaders were soon arrested. After a speedy and by no means impartial trial, five of the men—none of whom were ever proven to have a connection to the bombing—were sentenced to death. The bomber was never found. Haymarket Square itself no longer exists, but a plaque commemorates the spot, on a fairly desolate stretch of Des Plaines Street, just north of Randolph Street.

The city’s labor movement fought on. By the 1890s, many of Chicago’s workers were organized into the American Federation of Labor. The Pullman Strike of 1894 united black and white railway workers for the first time in a common struggle for higher wages and workplace rights. The Industrial Workers of the World, or the Wobblies, which embraced for a time so many great voices of American labor—Eugene V. Debs, Big Bill Haywood, and Helen Gurley Flynn—was founded in Chicago in 1905.

The Gangster Era

During the 1920s, the combination of Prohibition and a corrupt city administration happy to accept kickbacks from mobsters allowed organized crime to thrive. The most notorious local gangster of the era was a New York transplant named Al Capone, who muscled his way into control of the so-called Chicago Outfit. During his heyday, in the mid-1920s, Capone’s operations included bootlegging, speakeasies, gambling joints, brothels, and pretty much every other unsavory-but-profitable business; the Outfit’s take was reportedly $100 million a year.

Capone liked to promote himself as a humble, selfless business man—and he did set up soup kitchens at the start of the Great Depression—but he was also a ruthless thug who orchestrated gangland killings while always giving himself an alibi. The most notorious of these hits was the Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929, when four of Capone’s men killed seven members of a rival gang in a North Side garage. To gain access to the building, two of Capone’s gang dressed as policemen. Thinking it was a raid, the intended victims dropped their guns and put their hands up against the wall, only to be gunned down. The execution-style murder became national news, reinforcing Chicago’s already bloody reputation.

Notorious mobster Al Capone.

In the end, Capone and the Outfit were brought down by a combination of growing public outrage and federal government intervention. With the repeal of Prohibition, the gangsters’ main source of income was erased. At around the same time, an agent of the Internal Revenue Service put together evidence that Capone—who had never filed a tax return and claimed to have no income—was, in fact, earning plenty of cash. He was found guilty of tax evasion and served 7 years in prison, including a stint at Alcatraz in San Francisco. After his release, he retired to Florida and died of a heart attack in 1947, at the age of 48. Although the Chicago Outfit continued its shady dealings after Capone’s fall—using Las Vegas casinos for massive money-laundering operations—the city was no longer the site of vicious turf battles.

The Chicago Machine

While Chicago was becoming a center of industry, transportation, and finance, and a beacon of labor reform, it was also becoming a powerhouse in national politics. Between 1860 and 1968, Chicago was the site of 14 Republican and 10 Democratic presidential nominating conventions. (Some even point to the conventions as the source of Chicago’s “Windy City” nickname, laying the blame on politicians who were full of hot air.) The first of the conventions gave the country Abraham Lincoln; the 1968 convention saw the so-called Days of Rage, a series of increasingly violent confrontations between demonstrators protesting the Vietnam War and Chicago police officers. The simmering tension culminated in a riot in Grant Park, outside what’s now the Chicago Hilton; as police began beating protestors and bystanders with clubs and fists, TV cameras rolled, and demonstrators chanted, “The whole world is watching.”

And it was. The strong-arm tactics of Mayor Richard J. Daley—a supporter of eventual nominee Hubert Humphrey—made Humphrey look bad by association and may have contributed to Humphrey’s defeat in the general election. (Maybe it was a wash; some also say that Daley stole the 1960 election for Kennedy.) A national inquiry later declared the event a police-instigated riot, while the city’s own mayor-approved investigation blamed out-of-town extremists and provocateurs.

The supposed ringleaders of the uprising included Black Panther leader Bobby Seale; Tom Hayden, co-founder of Students for a Democratic Society; and Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, founders of the Youth International Party, or Yippies. They were charged with conspiracy and incitement to riot in the trial of the so-called Chicago 8 (later the Chicago 7, after charges in one case were dropped). Five were sentenced to prison terms, but their sentences were soon reversed after it was revealed that the FBI had bugged the offices of the defense lawyers.

The reversal was a setback for Mayor Daley, but his local power base held firm. The Democratic machine that he put in place during his years in office, from 1955 to 1976, was based on a practical sharing of the spoils: As long as the leaders of every ethnic and special interest group in town were guaranteed a certain number of government jobs, their leaders would bring in the votes.

Crowds protesting the 1968 Democratic National Convention, in defiance of Mayor Daley.

His reach extended well beyond Chicago’s borders; he controlled members of Congress, and every 4 years he delivered a solid Democratic vote in the November elections. But he also helped build Chicago into a modern business powerhouse, promoting the construction of O’Hare Airport, the McCormick Place Convention Center, and the Sears Tower, as well as expanding the city’s highway and subway systems. Since his death in 1976, the machine has never wielded such national power, but it still remains almost impossible for a Republican to be voted into local office.

While jobs in the factories, steel mills, and stockyards paid much better than those in the cotton fields, Chicago was not the paradise that many blacks envisioned. Segregation was almost as bad here as it was down South, and most blacks were confined to a narrow “Black Belt” of overcrowded apartment buildings on the South Side. But the new migrants made the best of their situation, and for a time in the 1930s and ’40s, the Black Belt—dubbed “Bronzeville” or the “Black Metropolis” by the community’s boosters—thrived as a cultural, musical, religious, and educational mecca. As journalist Nicholas Lemann writes in The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America, “Chicago was a city where a black person could be somebody.”

Some of the Southern migrants who made names for themselves in Chicago included black separatist and Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammed; Robert S. Abbott, publisher of the powerful Chicago Defender newspaper, who launched a “Great Northern Drive” to bring blacks to the city in 1917; Ida B. Wells, the crusading journalist who headed an antilynching campaign; William Dawson, for many years the only black congressman; New Orleans–born jazz pioneers “Jelly Roll” Morton, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong; Native Son author Richard Wright; John H. Johnson, publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines and one of Chicago’s wealthiest residents; blues musicians Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf; Thomas A. Dorsey, the “father of gospel music," and his greatest disciple, singer Mahalia Jackson; and Ralph Metcalfe, the Olympic gold medalist sprinter who turned to politics once he got to Chicago, eventually succeeding Dawson in Congress.

When a 1948 Supreme Court decision declared it unconstitutional to restrict blacks to certain neighborhoods, the flight of many Bronzeville residents to less crowded areas took a toll on the community. Through the 1950s, almost a third of the housing became vacant, and by the 1960s, the great social experiment of urban renewal through wholesale land clearance and the creation of large tracts of public housing gutted the once-thriving neighborhood.

Community and civic leaders now appear committed to restoring the neighborhood to a semblance of its former glory. Landmark status has been secured for several historic buildings in Bronzeville, including the Liberty Life/Supreme Insurance Company, 3501 S. King Dr., the first African-American–owned insurance company in the northern United States; and the Eighth Regiment Armory, which, when completed in 1915, was the only armory in the U.S. controlled by an African-American regiment. The former home of the legendary Chess Records at 2120 S. Michigan Ave.—where Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley gave birth to the blues and helped define rock ’n’ roll—now houses a museum and music education center. Willie Dixon’s widow, Marie Dixon, set up the Blues Heaven Foundation (312/808-1286; www.bluesheaven.com) with financial assistance from rock musician John Mellencamp. Along Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Drive, between 24th and 35th streets, several public art installations celebrate Bronzeville’s heritage. The most poignant is sculptor Alison Saar’s Monument to the Great Northern Migration, at King Drive and 26th Street, depicting a suitcase-toting African-American traveler standing atop a mound of worn shoe soles.

For information about tours of Bronzeville, see “Neighborhood Tours” in chapter 6.

chicago stories: The Great Migration

From 1915 to 1960, hundreds of thousands of black Southerners poured into Chicago, trying to escape segregation and seeking economic freedom and opportunity. The “Great Migration” radically transformed Chicago, both politically and culturally, from an Irish-run city of recent European immigrants into one in which no group had a majority and no politician—white or black—could ever take the black vote for granted. Unfortunately, the sudden change gave rise to many of the disparities that still plague the city, but it also promoted an environment in which many black men and women could rise from poverty to prominence.

Chicago’s Architecture

Although the Great Chicago Fire leveled almost 3 square miles of the downtown area in 1871, it did clear the stage for Chicago’s emergence as a breeding ground for innovative architecture. Some of the field’s biggest names—Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan, and Ludwig van der Rohe—made their mark on the city. And today Chicago’s skyline is home to iconic buildings, including the John Hancock Center and the (former) Sears Tower.

Early Skyscrapers (1880–1920)

In the late 19th century, important technical innovations—including safety elevators, fireproofing, and telecommunications—combined with advances in skeletal construction to create a new building type: the skyscraper. These buildings were spacious, cost-effective, efficient, and quick to build—in short, the perfect architectural solution for Chicago’s growing downtown. Architect Louis Sullivan (1865–1924) was the first to formalize a vision of a tall building based on the parts of a classical column. His theories inspired the Chicago school of architecture, examples of which still fill the city’s downtown. Features of Chicago school buildings include a rectangular shape with a flat roof; large windows (made possible by the development of load-bearing interior skeletons); and the use of terra cotta, a light, fireproof material that could be cast in any shape and attached to the exterior, often for decoration.

The gleaming white Wrigley Building.

A good example of the development of the skyscraper is the Monadnock Building, 53 W. Jackson Blvd. (Holabird & Root, 1889–91; Holabird & Roche, 1893). The northern section has 6-foot-thick walls at its base to support the building’s 17 stories; the newer, southern half has a steel frame clad in terra cotta (allowing the walls to be much thinner). The Reliance Building, now the Hotel Burnham, 1 W. Washington St. (Burnham & Root and Burnham & Co., 1891–95), was influential for its use of large glass windows and decorative spandrels (the horizontal panel below a window).

The Monadnock building, an early skyscraper.

Second Renaissance Revival (1890–1920)

The grand buildings of the Second Renaissance Revival, with their textural richness, suited the tastes of the wealthy Gilded Age. Typical features include a cubelike structure with a massive, imposing look; a symmetrical facade, including distinct horizontal divisions; and a different stylistic treatment for each floor, with different column capitals, finishes, and window treatments on each level. A fine example of this style is the Chicago Cultural Center, 78 E. Washington St. (Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, 1897), originally built as a public library. This tasteful edifice, with its sumptuous decor, was constructed in part to help secure Chicago’s reputation as a culture-conscious city.

A fine example of Second Renaissance Revival, the Chicago Cultural Center was originally built as a public library.

Beaux Arts (1890–1920)

This style takes its name from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where a number of prominent American architects received their training, beginning around the mid–19th century. In 1893, Chicago played host to the World’s Columbian Exposition, attended by 21 million people at a time when Chicago’s population was just over 1 million. Overseen by Chicagoan Daniel H. Burnham (1846–1912), the fairgrounds in Hyde Park were laid out in Beaux Arts style, with broad boulevards, fountains, and temporary ornate white buildings, mostly by New York–based architects. (One of the few permanent structures is now the Museum of Science and Industry.)

Grandiose compositions, exuberance of detail, and a variety of stone finishes typify most Beaux Arts structures. Chicago has several Beaux Arts buildings that exhibit the style’s main features. The oldest part of the Art Institute of Chicago, Michigan Avenue at Adams Street (Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, 1893), was built for the World’s Columbian Exposition. A later example of yet another skyscraper is the gleaming white Wrigley Building, 400–410 N. Michigan Ave. (Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, 1919–24), which serves as a gateway to North Michigan Avenue.

Art Deco (1925–33)

Art Deco buildings are characterized by a linear, hard edge or angular composition, often with a vertical emphasis and highlighted with stylized decoration. The Chicago Board of Trade, 141 W. Jackson Blvd. (Holabird & Root, 1930), punctuates LaSalle Street with its dramatic Art Deco facade. High atop the pyramidal roof, an aluminum statue of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, gazes down over the building. The last major construction project in Chicago before the Great Depression, 135 S. LaSalle St. (originally the Field Building; Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, 1934), has a magnificent Art Deco lobby. A fine example of an Art Deco town house is the Edward P. Russell House, 1444 N. Astor St. (Holabird & Root, 1929), in the city’s Gold Coast.

International Style (1932–45)

The International Style was popularized in the United States through the teachings and designs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), a German émigré who taught and practiced architecture in Chicago after leaving Germany’s influential Bauhaus school of design. In the 1950s, erecting a “Miesian” office building made companies appear progressive. Features of the style include a rectangular shape; the frequent use of glass; an absence of ornamentation; and a clear expression of the building’s form and function. (The interior structure of stacked office floors is clearly visible, as are the locations of mechanical systems, such as elevator shafts and air-conditioning units.)

Some famous Mies van der Rohe designs are the Chicago Federal Center, Dearborn Street between Adams Street and Jackson Boulevard (1959–74), and 860–880 N. Lake Shore Dr. (1949–51). Interesting interpretations of the style by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, a Chicago firm that helped make the International Style a corporate staple, are the Sears Tower (1968–74) and the John Hancock Center (1969)—impressive engineering feats that rise 110 and 100 stories, respectively.

Only in Chicago: the master builders

Visitors from around the world flock to Chicago to see the groundbreaking work of three major architects: Sullivan, Wright, and Mies. They all lived and worked in the Windy City, leaving behind a legacy of innovative structures that still inspire architects today. Here’s the rundown on each of them:

Louis Sullivan (1865–1924)

• Quote: “Form ever follows function.”

• Iconic Chicago building: Auditorium Building, 430 S. Michigan Ave. (1887–89).

• Innovations: Father of the Chicago school, Sullivan was perhaps at his most original in the creation of his intricate, nature-inspired ornamentation.

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959)

• Quote: “Nature is my manifestation of God.”

• Iconic Chicago building: Frederick C. Robie House, 5757 S. Woodlawn Ave., Hyde Park (1909).

• Innovations: While in Chicago, Wright developed the architecture of the Prairie School, a largely residential style combining natural materials, communication between interior and exterior spaces, and the sweeping horizontals of the Midwestern landscape. (For tours of Wright’s home and studio, see “Exploring the ’Burbs”.)

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969)

• Quote: “Less is more.”

• Iconic Chicago building: Chicago Federal Center, Dearborn Street between Adams Street and Jackson Boulevard (1959–74).

• Innovations: Mies van der Rohe brought the office tower of steel and glass to the United States. His stark facades don’t immediately reveal his careful attention to details and materials.

Postmodern (1975–90)

As a reaction against the stark International Style, postmodernists began to incorporate classical details and recognizable forms into their designs—often applied in outrageous proportions. One example, 190 S. LaSalle St. (John Burgee Architects with Philip Johnson, 1987), brings the shape of a famous Chicago building back to the skyline. The overall design is that of the 1892 Masonic Temple (now razed), complete with the tripartite divisions of the Chicago school. Another amalgam of historical precedents is the Harold Washington Library Center, 400 S. State St. (Hammond, Beeby & Babka, 1991). An extremely modern interpretation of a three-part skyscraper—but you have to look for the divisions to find them—is 333 Wacker Dr. (Kohn Pedersen Fox, 1979–83), an elegant green-glass structure that curves along a bend in the Chicago River. Unlike this harmonious juxtaposition, the James R. Thompson Center, 100 W. Randolph St. (Murphy/Jahn, 1979–85), inventively clashes with everything around it.

Chicago in Popular Culture

Books

So many great American writers have come from Chicago, lived here, or set their work in the city that it’s impossible to recommend a single book that says all there is to say about the city. But here are a few to get you started.

Upton Sinclair’s enormously influential The Jungle tells the tale of a young immigrant encountering the brutal, filthy city (see box, “Jungle Fever,” below). James T. Farrell’s trilogy Studs Lonigan, published in the 1930s, explores the power of ethnic and neighborhood identity in Chicago. Other novels set in Chicago include Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March and Humboldt’s Gift, and Richard Wright’s Native Son. The Time Traveler’s Wife, by local author Audrey Niffenegger, unfolds amid recognizable Chicago backdrops such as the Newberry Library. (The movie version, alas, filmed only a few scenes here.)

Upton Sinclair’s enormously influential The Jungle.

For an entertaining overview of the city’s history, read City of the Century, by Donald Miller (an excellent PBS special based on the book is also available on DVD). Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City, a history book that reads like a thriller, tells the engrossing story of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the serial killer who preyed on young women who visited from out of town. For another look at the seamy underside of Chicago’s history, try Sin in the Second City, by Karen Abbott, which focuses on the city’s most notorious—and expensive—brothel.

Two books give a human face to the city’s shameful public housing history: Daniel Coyle’s Hardball: A Season in the Projects, the true story of youngsters on a Little League baseball team; and Alex Kotlowitz’s There Are No Children Here, a portrait of children growing up in one of the city’s most dangerous projects. Kotlowitz also wrote Never a City So Real: A Walk in Chicago, which tells the stories of everyday Chicagoans, from a retired steelworker to a public defender, to the owner of a soul-food restaurant.

But no one has given a voice to the people of Chicago like Studs Terkel, whose books Division Street: America, Working, and Chicago are based on interviews with Chicagoans from every neighborhood and income level; and the late newspaper columnist Mike Royko, author of perhaps the definitive account of Chicago machine politics, Boss. His columns have been collected in One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko and For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko.

jungle Fever

It’s hard to get a man to understand something if his salary depends on him not understanding it.

—Upton Sinclair

The most influential work of Chicago-based literature may also be the most disturbing. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, an exposé of the city’s meatpacking industry, caused a sensation when it was published in 1906. Although the book is a novel, following the tragic life of a poorly paid Lithuanian immigrant, it was based on Sinclair’s firsthand observations at the Union Stockyards; many of its most gruesome scenes, such as when a man falls into a processing tank and is ground up along with the rest of the meat, were based on fact. After The Jungle became an international bestseller, U.S. meat exports plummeted and panicked meat-packing companies practically begged for government inspections to prove their products were safe. A Food and Drug Act was passed soon after, which made it a crime to sell food that had been adulterated or produced using “decomposed or putrid” substances; eventually, that led to the founding of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Film

Chicago became a popular setting for feature films in the 1980s and ’90s. For a look at Chicago on the silver screen, check out Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1985), the ultimate teenage wish-fulfillment fantasy, which includes scenes filmed at Wrigley Field and the city’s annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade; The Fugitive (1993), which used the city’s El trains as an effective backdrop; and My Best Friend’s Wedding (1996). For many Chicagoans, the quintessential hometown movie scene is the finale of The Blues Brothers (1979), which features a multicar pileup in the center of downtown Daley Plaza.

Sometimes locally born actors choose to shoot movies in their hometown. A film that fueled a thousand paparazzi photographs was The Break-Up (2006), starring local-boy-made-good Vince Vaughn and Jennifer Aniston, and filmed on location throughout the city. Another hometown actor, John Cusack, starred in High Fidelity (2000), where hip Wicker Park makes an appropriate backdrop for the tale of a music-obsessed record store owner. Director Michael Mann, a Chicago native, filmed part of the gangster movie Public Enemies (2009) in town—appropriately enough, since this was the place where bank robber John Dillinger (played by Johnny Depp in the movie) was caught and killed by federal agents.

Though it technically takes place in Gotham City, the setting of the Batman blockbuster The Dark Knight is clearly recognizable as Chicago—although, rest assured, the real city isn’t nearly as dark as the movie version! Swaths of downtown were also overrun by rampaging robots in Transformers 3 (2011).

Music

If Chicagoans were asked to pick one musical style to represent their city, most of us would start singing the blues. Thanks in part to the presence of the influential Chess Records, Chicago became a hub of blues activity after World War II, with musicians such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Buddy Guy recording and performing here. (For a glimpse of what the music studio was like in its glory days, rent the 2008 movie Cadillac Records, starring Jeffrey Wright as Muddy Waters and Beyoncé Knowles as Etta James.) Buddy Guy is still active on the local scene, making regular appearances at his eponymous downtown blues club, one of the best live music venues in the city.

A Chicago playlist

The classic swingin’ anthem of the city is Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “Chicago” (“That toddlin’ town . . . free and easy town, brassy, breezy town”), overblown versions of which show up regularly at local karaoke bars. Sinatra also sang his praises to the city in “My Kind of Town (Chicago Is),” which mentions the Wrigley Building and the Union Stockyards. But an even better pick for official city theme song is Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago,” with its appropriately bluesy riff (“Come on, baby don’t you want to go, to the same old place, Sweet Home Chicago”). The 1970s pop-lite group Chicago didn’t sing specifically about the city (probably because they moved to L.A. as soon as they hit it big), but their cheery “Saturday in the Park” captures the spirit of Grant Park and Lincoln Park in the summertime. Fast-forwarding a few decades, the blistering “Cherub Rock” by Smashing Pumpkins is a harsh take on the city’s 1990s-era music scene (opening with the line: “Freak out, give in, doesn’t matter what you believe in . . .”); more mellow is the elegiac “Via Chicago” by indie darlings Wilco. And no survey of Chicago music would be complete without mentioning the maestros of hip-hop, Common and Kanye West, who name-check their hometown in the songs “Southside” and “Homecoming,” respectively.

In the ’60s and ’70s, Chicago helped usher in the era of “electric blues”—low-tech, soulful singing melded with the rock sensibility of electric guitars. Blues-influenced rock musicians, including the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Eric Clapton, made Chicago a regular pilgrimage spot.

Blues legend Muddy Waters.

Today the blues has become yet another tourist attraction, especially for international visitors, but the quality and variety of blues acts is still impressive. Hard-core blues fans shouldn’t miss the annual (free) Blues Fest, held along the lakefront in Grant Park in early June. For a listing of the city’s best blues clubs, see chapter 9.

Don’t miss the annual, free Blues Fest in Grant Park.

Eating & Drinking

Joke all you want about bratwurst and deep-dish pizza; Chicago is a genuine culinary hot spot. One of the city’s most creative dining spots, Alinea, was even named the top restaurant in the United States by Gourmet magazine in 2007 (take that, New York and San Francisco!). What makes eating out in Chicago fun is the variety. We’ve got it all: stylish see-and-be-seen spots, an amazing array of steakhouses, chef-owned temples to fine dining, and every kind of ethnic cuisine you could possibly crave—plus, yes, some not-to-be-missed deep-dish pizza places.

Fueled in part by expense-account-wielding business travelers, high-end dining is a growth industry here. What makes Chicago’s top restaurants unique, however, is their inclusive, low-key attitude. This isn’t the kind of city where snooty waiters show off their foodie expertise or stare in horror if you have no idea what wine to order. By and large, hospitality is more than just a buzzword here, and as long as you can afford the eye-popping bill, the city’s top chefs will welcome you. If you want to splurge on a one-of-a-kind meal—the kind you’ll be describing to friends weeks later—Chicago is the place to do it. (See chapter 5, “Where to Eat.”)

That said, ever-increasing restaurant prices are one of my pet peeves; eating out downtown has become more and more of a luxury. While finding bargains in the Loop or around the Magnificent Mile isn’t easy, you can still fill up without going broke by stopping at one of the food courts inside the malls along Michigan Avenue (as many locals on their lunch break do). Ethnic restaurants also tend to be less expensive, whether you’re sampling spanakopita in Greektown or a noodle dish at a Thai restaurant (see the box “A Taste of Thai”).

And about that pizza: Yes, Chicagoans hate to be stereotyped as cheese-and-sausage-devouring slobs, but we really do eat deep-dish pizza, which was created in the 1940s at the original Pizzeria Uno restaurant. If you’ve never had this decadent, cholesterol-raising delicacy, you should definitely try it while you’re here (especially on a chilly day—it’s not as appealing during a summer heat wave). You’ll find a rundown of the best pizza spots.

Deep dish pizza is a Chicago tradition.

When to Go

You’ll see Chicago at its best if you visit during the summer or fall. Summer offers a nonstop selection of special events and outdoor activities; the downside is that you’ll be dealing with the biggest crowds and periods of hot, muggy weather. Autumn days are generally sunny, and the crowds at major tourist attractions grow thinner—you don’t have to worry about snow until late November at the earliest. Spring is extremely unpredictable, with dramatic fluctuations of cold and warm weather, and usually fair amounts of rain. If your top priority is indoor cultural sights, winter’s not such a bad time to visit: no lines at museums, the cheapest rates at hotels, and the pride that comes with slogging through the slush with the natives.

When planning your trip, book a hotel as early as possible, especially if you’re coming during the busy summer tourist season. The more affordable a hotel, the more likely it is to be sold out in June, July, and August, especially on weekends. It’s also worth checking if a major convention will be in town during the dates you hope to travel (see the “Major Convention Dates” box, later). It’s not unusual for every major downtown hotel to be sold out during the Housewares Show in late March or the Restaurant Show in mid-May.

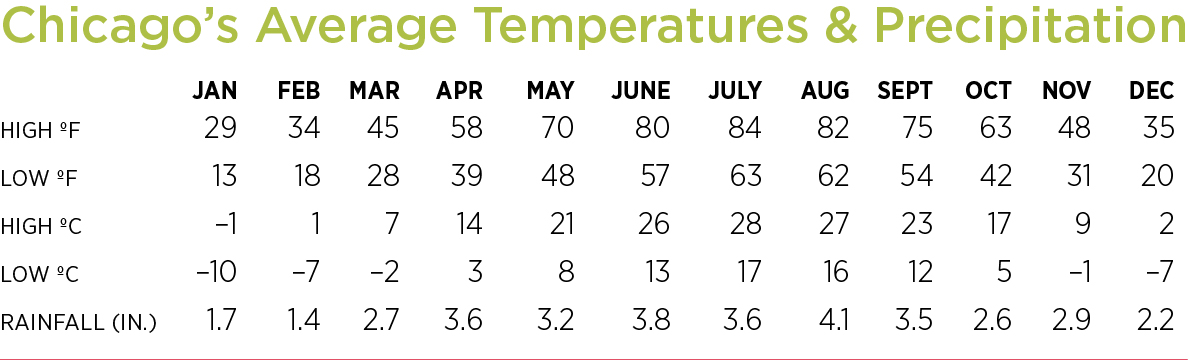

Weather

Chicagoans like to joke that if you don’t like the weather, just wait an hour—it will change. In spring and autumn, be prepared for a wide range of temperatures; you may be shivering in a coat and gloves in the morning, only to be fine in a T-shirt by mid-afternoon. While Chicago winters get a bad rap, they’re no worse than in other northern American cities. January isn’t exactly prime tourist season, but the city doesn’t shut down; as long as you’ve got the proper cold-weather gear and sturdy boots, you should be fine. Summers are generally warm and sunny, with temperatures that range from pleasant to steamy. The closer you are to the lake, the more you’ll benefit from the cool breezes that float off the water.

As close to your departure as possible, check the local weather forecast at the websites of the Chicago Tribune newspaper (www.chicagotribune.com) or the Weather Channel (www.weather.com). You’ll find packing a lot easier if you know whether to expect snow, rain, or sweltering heat. (That said, bring a range of clothes and an umbrella if you’re going to be in town for awhile—you should be prepared for anything!)

Holidays

Banks, government offices, post offices, and many stores, restaurants, and museums are closed on the following legal national holidays: January 1 (New Year’s Day), the third Monday in January (Martin Luther King, Jr., Day), the third Monday in February (Presidents’ Day), the last Monday in May (Memorial Day), July 4 (Independence Day), the first Monday in September (Labor Day), the second Monday in October (Columbus Day), November 11 (Veterans’ Day/Armistice Day), the fourth Thursday in November (Thanksgiving Day), and December 25 (Christmas). The Tuesday after the first Monday in November is Election Day, a federal government holiday in presidential-election years (held every 4 years, and next in 2012).

Chicago Calendar of Events

The best way to stay on top of the city’s current crop of special events is to check in with the Chicago Convention & Tourism Bureau ( 877/CHICAGO [244-2246]; www.choosechicago.com). Visit their website to browse the Chicago Destination Guide, which surveys special events, including parades, street festivals, concerts, theatrical productions, and museum exhibitions (you can also get a copy mailed to you). The Mayor’s Office of Special Events (

877/CHICAGO [244-2246]; www.choosechicago.com). Visit their website to browse the Chicago Destination Guide, which surveys special events, including parades, street festivals, concerts, theatrical productions, and museum exhibitions (you can also get a copy mailed to you). The Mayor’s Office of Special Events ( 312/744-3315) lets you search for upcoming festivals, parades, and concerts on its website, www.explorechicago.org.

312/744-3315) lets you search for upcoming festivals, parades, and concerts on its website, www.explorechicago.org.

For an exhaustive list of events beyond those listed here, check http://events.frommers.com, where you’ll find a searchable, up-to-the-minute roster of what’s happening in cities all over the world.

January

Chicago Boat, RV & Outdoor Show, McCormick Place, 23rd Street and Lake Shore Drive ( 312/946-6200; www.chicagoboatshow.com). All the latest boats and recreational vehicles are on display, plus trout fishing, a climbing wall, boating safety seminars, and big-time entertainment. January 11 to 15, 2012.

312/946-6200; www.chicagoboatshow.com). All the latest boats and recreational vehicles are on display, plus trout fishing, a climbing wall, boating safety seminars, and big-time entertainment. January 11 to 15, 2012.

Winter Delights. Throughout January and February, the city’s Office of Tourism ( 877/CHICAGO [244-2246]; www.choosechicago.com) offers special travel deals to lure visitors during tourism’s low season. Incentives include bargain-priced hotel packages, affordable prix-fixe dinners at downtown restaurants, and special music and theater performances. Early January through February.

877/CHICAGO [244-2246]; www.choosechicago.com) offers special travel deals to lure visitors during tourism’s low season. Incentives include bargain-priced hotel packages, affordable prix-fixe dinners at downtown restaurants, and special music and theater performances. Early January through February.

Chinese New Year Parade, Wentworth and Cermak streets ( 312/326-5320; www.chicagochinatown.org). Join in as the sacred dragon whirls down the boulevard and restaurateurs pass out small envelopes of money to their regular customers. In 2012, Chinese New Year begins on January 23; call to verify the date of the parade.

312/326-5320; www.chicagochinatown.org). Join in as the sacred dragon whirls down the boulevard and restaurateurs pass out small envelopes of money to their regular customers. In 2012, Chinese New Year begins on January 23; call to verify the date of the parade.

February

Chicago Auto Show, McCormick Place, 23rd Street and Lake Shore Drive ( 630/495-2282; www.chicagoautoshow.com). More than 1,000 cars and trucks, domestic and foreign, current and futuristic, are on display. The event draws nearly a million visitors, so try to visit on a weekday rather than Saturday or Sunday. Many area hotels offer special packages that include show tickets. February 10 to 19, 2012.

630/495-2282; www.chicagoautoshow.com). More than 1,000 cars and trucks, domestic and foreign, current and futuristic, are on display. The event draws nearly a million visitors, so try to visit on a weekday rather than Saturday or Sunday. Many area hotels offer special packages that include show tickets. February 10 to 19, 2012.

March

St. Patrick’s Day Parade. In a city with a strong Irish heritage, this holiday is a big deal. The Chicago River is even dyed green for the occasion. The parade route is along Columbus Drive from Balbo Drive to Monroe Street. A second, more neighborhood-like parade is held on the South Side the day after the Dearborn Street parade, on Western Avenue from 103rd to 115th streets. Visit www.chicagostpatsparade.com for information. The Saturday before March 17.

April

Opening Day. For the Cubs, call  773/404-CUBS [2827] or visit www.cubs.mlb.com; for the White Sox, call

773/404-CUBS [2827] or visit www.cubs.mlb.com; for the White Sox, call  312/674-1000 or go to www.whitesox.mlb.com. Make your plans early to get tickets for this eagerly awaited day. The calendar may say spring, but be warned: Opening Day is usually freezing in Chi-town. (The first Cubs and Sox home games have occasionally been postponed because of snow.) Early April.

312/674-1000 or go to www.whitesox.mlb.com. Make your plans early to get tickets for this eagerly awaited day. The calendar may say spring, but be warned: Opening Day is usually freezing in Chi-town. (The first Cubs and Sox home games have occasionally been postponed because of snow.) Early April.

Chicago Improv Festival. Chicago’s improv comedy scene is known as a training ground for performers who have gone on to shows such as Saturday Night Live or MADtv. Big names and lesser-known (but talented) comedians converge for a celebration of silliness, with large main-stage shows and smaller, more experimental pieces. Most performances are at the Lakeshore Theater on the North Side (3175 N. Broadway;  773/472-3492; www.chicagoimprovfestival.org). Late April.

773/472-3492; www.chicagoimprovfestival.org). Late April.

May

Buckingham Fountain Color Light Show, Congress Parkway and Lake Shore Drive. This massive, landmark fountain in Grant Park operates daily from May 1 to October 1. From sundown to 11pm, a colored light show adds to the drama.

The Ferris Wheel and Carousel begin spinning again at Navy Pier, 600 E. Grand Ave. ( 312/595-PIER [7437]; www.navypier.com). The rides operate through October. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, Navy Pier also hosts twice-weekly fireworks shows Wednesday nights at 9:30pm and Saturday nights at 10:15pm.

312/595-PIER [7437]; www.navypier.com). The rides operate through October. From Memorial Day through Labor Day, Navy Pier also hosts twice-weekly fireworks shows Wednesday nights at 9:30pm and Saturday nights at 10:15pm.

Art Chicago, the Merchandise Mart, at the intersection of Kinzie and Wells streets ( 312/527-3701; www.artchicago.com). The city’s biggest contemporary art show brings together collectors, art lovers, and gallery owners from throughout the Midwest. You don’t have to be an expert to check out the show: Tours and educational programs are offered to make the work accessible to art novices. The Next show, which runs concurrently, focuses on work by emerging international artists. First week in May.

312/527-3701; www.artchicago.com). The city’s biggest contemporary art show brings together collectors, art lovers, and gallery owners from throughout the Midwest. You don’t have to be an expert to check out the show: Tours and educational programs are offered to make the work accessible to art novices. The Next show, which runs concurrently, focuses on work by emerging international artists. First week in May.

Celtic Fest Chicago, Pritzker Music Pavilion, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, in Millennium Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). This festival celebrates the music and dance of global Celtic traditions. But the mood is far from reverential: There’s a limerick contest and a “best legs” contest exclusively for men wearing kilts. First weekend in May.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). This festival celebrates the music and dance of global Celtic traditions. But the mood is far from reverential: There’s a limerick contest and a “best legs” contest exclusively for men wearing kilts. First weekend in May.

Wright Plus Tour, Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, Oak Park ( 708/848-1976; www.wrightplus.org). This annual tour of 10 buildings, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio, the Unity Temple, and several other notable buildings in both Prairie and Victorian styles, is very popular, so plan on buying tickets in advance (they go on sale March 1). Third Saturday in May.

708/848-1976; www.wrightplus.org). This annual tour of 10 buildings, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio, the Unity Temple, and several other notable buildings in both Prairie and Victorian styles, is very popular, so plan on buying tickets in advance (they go on sale March 1). Third Saturday in May.

June

Chicago Gospel Festival, Pritzker Music Pavilion, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, Millennium Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Blues may be the city’s most famous musical export, but Chicago is also the birthplace of gospel music: Thomas Dorsey, the “father of gospel,” and the greatest gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, were from the city’s South Side. This 3-day festival—the largest outdoor, free-admission event of its kind—offers music on three stages with more than 40 performances. First weekend in June.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Blues may be the city’s most famous musical export, but Chicago is also the birthplace of gospel music: Thomas Dorsey, the “father of gospel,” and the greatest gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, were from the city’s South Side. This 3-day festival—the largest outdoor, free-admission event of its kind—offers music on three stages with more than 40 performances. First weekend in June.

Printers Row Lit Fest, Dearborn Street from Congress Parkway to Polk Street ( 312/222-3986; http://printersrowlitfest.org). One of the largest free outdoor book fairs in the country, this weekend event celebrates the written word with everything from readings and signings by big-name authors to panel discussions on penning your first novel. Located within walking distance of the Loop, the fair also features more than 150 booksellers with new, used, and antiquarian books; a poetry tent; and special activities for children. First weekend in June.

312/222-3986; http://printersrowlitfest.org). One of the largest free outdoor book fairs in the country, this weekend event celebrates the written word with everything from readings and signings by big-name authors to panel discussions on penning your first novel. Located within walking distance of the Loop, the fair also features more than 150 booksellers with new, used, and antiquarian books; a poetry tent; and special activities for children. First weekend in June.

Chicago Blues Festival, Petrillo Music Shell, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, Grant Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Muddy Waters would scratch his noggin over the sea of suburbanites who flood into Grant Park every summer to quaff Budweisers and accompany local legends Buddy Guy and Lonnie Brooks on air guitar. Truth be told, you can hear the same great jams and wails virtually any night of the week in one of the city’s many blues clubs. Still, a thousand-voice chorus of “Sweet Home Chicago” under the stars has a rousing appeal. All concerts at the Blues Fest are free, with dozens of acts performing over 3 days, but get there in the afternoon to get a good spot on the lawn for the evening show. Second weekend in June.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Muddy Waters would scratch his noggin over the sea of suburbanites who flood into Grant Park every summer to quaff Budweisers and accompany local legends Buddy Guy and Lonnie Brooks on air guitar. Truth be told, you can hear the same great jams and wails virtually any night of the week in one of the city’s many blues clubs. Still, a thousand-voice chorus of “Sweet Home Chicago” under the stars has a rousing appeal. All concerts at the Blues Fest are free, with dozens of acts performing over 3 days, but get there in the afternoon to get a good spot on the lawn for the evening show. Second weekend in June.

Ravinia Festival, Ravinia Park, Highland Park ( 847/266-5100; www.ravinia.com). This suburban location is the open-air summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the venue of many first-rate visiting orchestras, chamber ensembles, pop artists, and dance companies. See also “Exploring the ’Burbs,” in chapter 6. June through September.

847/266-5100; www.ravinia.com). This suburban location is the open-air summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the venue of many first-rate visiting orchestras, chamber ensembles, pop artists, and dance companies. See also “Exploring the ’Burbs,” in chapter 6. June through September.

Puerto Rican Fest, Humboldt Park, Division Street and Sacramento Boulevard ( 773/292-1414; http://prparadechicago.org). One of the city’s largest festivals, this celebration includes 5 days of live music, theater, games, food, and beverages. It peaks with a parade that winds its way from Wacker Drive and Dearborn Street to the West Side Puerto Rican enclave of Humboldt Park. Mid-June.

773/292-1414; http://prparadechicago.org). One of the city’s largest festivals, this celebration includes 5 days of live music, theater, games, food, and beverages. It peaks with a parade that winds its way from Wacker Drive and Dearborn Street to the West Side Puerto Rican enclave of Humboldt Park. Mid-June.

Old Town Art Fair, Lincoln Park West and Wisconsin Street, Old Town ( 312/337-1938; www.oldtowntriangle.com). This juried fine arts fair has drawn browsers to this historic neighborhood for more than 50 years with the work of more than 250 painters, sculptors, and jewelry designers from the Midwest and around the country on display. It also features an art auction, garden walk, concessions, and children’s art activities. It tends to get crowded, but the overall vibe is low-key festive rather than rowdy. Second weekend in June.

312/337-1938; www.oldtowntriangle.com). This juried fine arts fair has drawn browsers to this historic neighborhood for more than 50 years with the work of more than 250 painters, sculptors, and jewelry designers from the Midwest and around the country on display. It also features an art auction, garden walk, concessions, and children’s art activities. It tends to get crowded, but the overall vibe is low-key festive rather than rowdy. Second weekend in June.

Wells Street Art Festival, Wells Street from North Avenue to Division Street ( 312/951-6106; www.oldtownchicago.org). Held on the same weekend as the more prestigious Old Town Art Fair, this event is lots of fun, with 200 arts and crafts vendors, food, music, and carnival rides. Second weekend in June.

312/951-6106; www.oldtownchicago.org). Held on the same weekend as the more prestigious Old Town Art Fair, this event is lots of fun, with 200 arts and crafts vendors, food, music, and carnival rides. Second weekend in June.

Grant Park Music Festival, Pritzker Music Pavilion, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, in Millennium Park ( 312/742-7638; www.grantparkmusicfestival.com). One of the city’s greatest bargains, this classical music series presents free concerts in picture-perfect Millennium Park. Many of the musicians are members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the shows often feature internationally known singers and performers. Bring a picnic and enjoy dinner beforehand with a view of the skyline. Concerts begin the last week in June and continue through August.

312/742-7638; www.grantparkmusicfestival.com). One of the city’s greatest bargains, this classical music series presents free concerts in picture-perfect Millennium Park. Many of the musicians are members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the shows often feature internationally known singers and performers. Bring a picnic and enjoy dinner beforehand with a view of the skyline. Concerts begin the last week in June and continue through August.

Taste of Chicago, Grant Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). The city claims that this is the largest free outdoor food fest in the nation. Three and a half million rib and pizza lovers feeding at this colossal alfresco trough say they’re right. Over 10 days of feasting in the streets, scores of Chicago restaurants cart their fare to food stands set up throughout the park. To avoid the heaviest crowds, try going on weekdays earlier in the day. Claustrophobes, take note: If you’re here the evening of July 3 for the Independence Day fireworks, pick out a vantage point farther north on the lakefront—unless dodging sweaty limbs, spilled beer, and the occasional bottle rocket sounds fun. Admission is free; you pay for the sampling. June 27 through July 6, 2012.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). The city claims that this is the largest free outdoor food fest in the nation. Three and a half million rib and pizza lovers feeding at this colossal alfresco trough say they’re right. Over 10 days of feasting in the streets, scores of Chicago restaurants cart their fare to food stands set up throughout the park. To avoid the heaviest crowds, try going on weekdays earlier in the day. Claustrophobes, take note: If you’re here the evening of July 3 for the Independence Day fireworks, pick out a vantage point farther north on the lakefront—unless dodging sweaty limbs, spilled beer, and the occasional bottle rocket sounds fun. Admission is free; you pay for the sampling. June 27 through July 6, 2012.

Gay and Lesbian Pride Parade, Halsted Street, from Belmont Avenue to Broadway, south to Diversey Parkway, and east to Lincoln Park, where a rally and music festival are held ( 773/348-8243; www.chicagopridecalendar.org). This parade is the colorful culmination of a month of activities by Chicago’s gay and lesbian communities. Halsted Street is usually mobbed; pick a spot on Broadway for a better view. Last Sunday in June.

773/348-8243; www.chicagopridecalendar.org). This parade is the colorful culmination of a month of activities by Chicago’s gay and lesbian communities. Halsted Street is usually mobbed; pick a spot on Broadway for a better view. Last Sunday in June.

July

Independence Day Celebration ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Chicago celebrates the holiday on July 3 with a free classical music concert in Grant Park in the evening, followed by fireworks over the lake. Expect huge crowds. July 3.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Chicago celebrates the holiday on July 3 with a free classical music concert in Grant Park in the evening, followed by fireworks over the lake. Expect huge crowds. July 3.

Old St. Patrick’s World’s Largest Block Party, 700 W. Adams St., at Des Plaines Avenue ( 312/648-1021; www.oldstpats.org). This hugely popular blowout is hosted by the city’s oldest church, an Irish Catholic landmark in the West Loop area. It can get pretty crowded, but Old St. Pat’s always lands some major acts. Six bands perform over 2 nights on two stages and attract a young, lively crowd. Second weekend in July.

312/648-1021; www.oldstpats.org). This hugely popular blowout is hosted by the city’s oldest church, an Irish Catholic landmark in the West Loop area. It can get pretty crowded, but Old St. Pat’s always lands some major acts. Six bands perform over 2 nights on two stages and attract a young, lively crowd. Second weekend in July.

Chicago Yacht Club’s Race to Mackinac Island, starting line at the Monroe Street Harbor ( 312/861-7777; www.chicagoyachtclub.org). This 3-day competition is the grandest of the inland water races. The public is welcome at a Friday night party. On Saturday, jockey for a good place to watch the boats set sail toward northern Michigan. Mid-July.

312/861-7777; www.chicagoyachtclub.org). This 3-day competition is the grandest of the inland water races. The public is welcome at a Friday night party. On Saturday, jockey for a good place to watch the boats set sail toward northern Michigan. Mid-July.

Sheffield Garden Walk, starting at Sheffield and Webster avenues ( 773/929-9255; www.sheffieldfestivals.org). More than 50 Lincoln Park homeowners open their back yards to visitors at this annual event, giving you a chance to snoop around these normally hidden retreats. The walk isn’t just for garden nuts; it has also grown into a lively street festival, with live bands, children’s activities, and food and drink tents. It’s a popular destination for a wide cross-section of Chicagoans, from singles to young families to retirees. Third weekend in July.

773/929-9255; www.sheffieldfestivals.org). More than 50 Lincoln Park homeowners open their back yards to visitors at this annual event, giving you a chance to snoop around these normally hidden retreats. The walk isn’t just for garden nuts; it has also grown into a lively street festival, with live bands, children’s activities, and food and drink tents. It’s a popular destination for a wide cross-section of Chicagoans, from singles to young families to retirees. Third weekend in July.

Dearborn Garden Walk & Heritage Festival, North Dearborn and Astor streets ( 312/632-1241; www.dearborngardenwalk.com). A more upscale affair than the Sheffield Garden Walk, this event allows regular folks to peer into private gardens on the Gold Coast, one of the most expensive and exclusive neighborhoods in the city. As you’d expect, many yards are the work of the best landscape architects, designers, and art world luminaries that old money can buy. There’s also live music, a marketplace, and a few architectural tours. Third Sunday in July.

312/632-1241; www.dearborngardenwalk.com). A more upscale affair than the Sheffield Garden Walk, this event allows regular folks to peer into private gardens on the Gold Coast, one of the most expensive and exclusive neighborhoods in the city. As you’d expect, many yards are the work of the best landscape architects, designers, and art world luminaries that old money can buy. There’s also live music, a marketplace, and a few architectural tours. Third Sunday in July.

Chicago SummerDance, east side of South Michigan Avenue between Balbo and Harrison streets ( 312/742-4007; www.explorechicago.org). From July through late August, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs transforms a patch of Grant Park into a lighted outdoor dance venue on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday from 6 to 9:30pm, and Sunday from 4 to 7pm. The 4,600-square-foot dance floor provides ample room for throwing down moves while live bands play music—from ballroom and klezmer to samba and zydeco. One-hour lessons are offered from 6 to 7pm. Free admission.

312/742-4007; www.explorechicago.org). From July through late August, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs transforms a patch of Grant Park into a lighted outdoor dance venue on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday from 6 to 9:30pm, and Sunday from 4 to 7pm. The 4,600-square-foot dance floor provides ample room for throwing down moves while live bands play music—from ballroom and klezmer to samba and zydeco. One-hour lessons are offered from 6 to 7pm. Free admission.

Taste of Lincoln Avenue, Lincoln Park, between Fullerton Avenue and Wellington Street ( 773/868-3010; www.wrightwoodneighbors.org). This is one of the largest and most popular of Chicago’s many neighborhood street fairs; it features 50 bands performing music on five stages. Neighborhood restaurants staff the food stands, and there’s also a kids’ carnival. Last weekend in July.

773/868-3010; www.wrightwoodneighbors.org). This is one of the largest and most popular of Chicago’s many neighborhood street fairs; it features 50 bands performing music on five stages. Neighborhood restaurants staff the food stands, and there’s also a kids’ carnival. Last weekend in July.

Newberry Library Book Fair & Bughouse Square Debates, 69 W. Walton St. and Washington Square Park ( 312/255-3501; www.newberry.org). Over 4 days, the esteemed Newberry Library invites the masses to rifle through bins stuffed with tens of thousands of used books, most of which go for a few dollars. Better than the book fair is what happens across the street in Washington Square Park: soapbox orators re-creating the days when left-wing agitators came here to make their case. Late July.

312/255-3501; www.newberry.org). Over 4 days, the esteemed Newberry Library invites the masses to rifle through bins stuffed with tens of thousands of used books, most of which go for a few dollars. Better than the book fair is what happens across the street in Washington Square Park: soapbox orators re-creating the days when left-wing agitators came here to make their case. Late July.

August

Northalsted Market Days, Halsted Street between Belmont Avenue and Addison Street ( 773/883-0500; www.northalsted.com). The largest of the city’s street festivals, held in the heart of the North Side’s gay-friendly neighborhood, Northalsted Market Days offers music on three stages, lots of food and offbeat merchandise, and some of the best people-watching of the summer. First weekend in August.

773/883-0500; www.northalsted.com). The largest of the city’s street festivals, held in the heart of the North Side’s gay-friendly neighborhood, Northalsted Market Days offers music on three stages, lots of food and offbeat merchandise, and some of the best people-watching of the summer. First weekend in August.

Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic, starting at 39th Street and King Drive and ending at 55th Street and Washington Park ( 773/536-3710; www.budbillikenparade.com). This annual African-American celebration, which has been held for more than 80 years, is one of the oldest parades of its kind in the nation. It’s named for the mythical figure Bud Billiken, reputedly the patron saint of “the little guy,” and features the standard floats, bands, marching and military units, drill teams, and glad-handing politicians. Second Saturday in August.

773/536-3710; www.budbillikenparade.com). This annual African-American celebration, which has been held for more than 80 years, is one of the oldest parades of its kind in the nation. It’s named for the mythical figure Bud Billiken, reputedly the patron saint of “the little guy,” and features the standard floats, bands, marching and military units, drill teams, and glad-handing politicians. Second Saturday in August.

Chicago Air & Water Show, North Avenue Beach ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). The U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds and Navy Seals usually make an appearance at this hugely popular aquatic and aerial spectacular. (Even if you don’t plan to watch it, you can’t help but experience it with jets screaming overhead all weekend.) Expect huge crowds, so arrive early if you want a spot along the water, or park yourself on the grass along the east edge of Lincoln Park Zoo, where you’ll get good views (and some elbow room). Free admission. Third weekend in August.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). The U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds and Navy Seals usually make an appearance at this hugely popular aquatic and aerial spectacular. (Even if you don’t plan to watch it, you can’t help but experience it with jets screaming overhead all weekend.) Expect huge crowds, so arrive early if you want a spot along the water, or park yourself on the grass along the east edge of Lincoln Park Zoo, where you’ll get good views (and some elbow room). Free admission. Third weekend in August.

September

Chicago Jazz Festival, Petrillo Music Shell, Jackson and Columbus drives, Grant Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Several national headliners are always on hand at this steamy gathering, which provides a swell end-of-summer bookend opposite to the gospel and blues fests in June. The event is free; come early and stay late. First weekend in September.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Several national headliners are always on hand at this steamy gathering, which provides a swell end-of-summer bookend opposite to the gospel and blues fests in June. The event is free; come early and stay late. First weekend in September.

The art season, in conjunction with the annual Visions series of art gallery programs for the general public, begins with galleries holding their season openers in the Loop, River North, River West, and Wicker Park/Bucktown gallery districts. Contact the Chicago Art Dealers Association ( 312/649-0065; www.chicagoartdealers.org) for details. First Friday after Labor Day.

312/649-0065; www.chicagoartdealers.org) for details. First Friday after Labor Day.

Boulevard Lakefront Bike Tour (Active Transit Alliance;  312/427-3325; www.activetrans.org). This 35-mile leisurely bicycle excursion is a great way to explore the city, from the neighborhoods to the historic link of parks and boulevards. There’s also a 10-mile tour for children and families. The Sunday morning event starts and ends at the University of Chicago in Hyde Park, which plays host to vendors and entertainment at the annual Bike Expo. Mid-September.

312/427-3325; www.activetrans.org). This 35-mile leisurely bicycle excursion is a great way to explore the city, from the neighborhoods to the historic link of parks and boulevards. There’s also a 10-mile tour for children and families. The Sunday morning event starts and ends at the University of Chicago in Hyde Park, which plays host to vendors and entertainment at the annual Bike Expo. Mid-September.

Mexican Independence Day Parade, Dearborn Street between Wacker Drive and Van Buren Street ( 312/744-3315). This parade is on Saturday; another takes place the next day on 26th Street in the Little Village neighborhood (

312/744-3315). This parade is on Saturday; another takes place the next day on 26th Street in the Little Village neighborhood ( 773/521-5387). Second Saturday in September.

773/521-5387). Second Saturday in September.

Viva! Chicago Latin Music Festival, Pritzker Music Pavilion, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, in Millennium Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). This free musical celebration features salsa, mambo, and performances by the hottest Latin rock acts. Free admission. Third weekend in September.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). This free musical celebration features salsa, mambo, and performances by the hottest Latin rock acts. Free admission. Third weekend in September.

October

Chicago International Film Festival ( 312/683-0121; www.chicagofilmfestival.org). The oldest U.S. festival of its kind screens films from around the world, as well as a few high-profile American independent films. It’s a great way to catch foreign movies that may never be released in the U.S. Screenings take place over 2 weeks, with most held at downtown movie theaters that are easily accessible to visitors. First 2 weeks of October.

312/683-0121; www.chicagofilmfestival.org). The oldest U.S. festival of its kind screens films from around the world, as well as a few high-profile American independent films. It’s a great way to catch foreign movies that may never be released in the U.S. Screenings take place over 2 weeks, with most held at downtown movie theaters that are easily accessible to visitors. First 2 weeks of October.

Chicago Country Music Festival, Pritzker Music Pavilion, Randolph Street and Columbus Drive, in Millennium Park ( 312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Chicago may be a long way from Dixie, but country music still has a loyal Midwest fan base. This popular event features free concerts from big-name entertainers. First weekend in October.

312/744-3315; www.explorechicago.org). Chicago may be a long way from Dixie, but country music still has a loyal Midwest fan base. This popular event features free concerts from big-name entertainers. First weekend in October.

Chicago Marathon ( 312/904-9800; www.chicagomarathon.com). Sponsored by Bank of America, Chicago’s marathon is a major event on the international long-distance running circuit. It begins and ends in Grant Park but can be viewed from any number of vantage points along the route. Second Sunday in October.

312/904-9800; www.chicagomarathon.com). Sponsored by Bank of America, Chicago’s marathon is a major event on the international long-distance running circuit. It begins and ends in Grant Park but can be viewed from any number of vantage points along the route. Second Sunday in October.

November

The Chicago Humanities Festival takes over locations throughout downtown, from libraries to concert halls ( 312/661-1028; www.chfestival.org). Over a 2-week period, the festival presents cultural performances, readings, and symposiums tied to an annual theme (recent themes included “Brains & Beauty” and “Crime & Punishment”). Expect appearances by major authors, scholars, and policymakers, all at a very reasonable cost (usually $5–$10 per event). Early November.