J.H.S. 72 Catherine & Count Basie Middle School, Jamaica, Queens

February 29, 2012

A few days after the near debacle in East Harlem, angry white applicants gathered forces and tried again, with help from Merit Matters. This time it was at a Vulcan Society tutoring session at a school in Queens. Paul Washington wasn’t able to attend, but after what had happened in Harlem he knew some last-minute instructions were necessary for the Vulcans who were going to oversee things.

“We know there’s likely going to be some mischief,” he said in phone calls to FDNY lieutenant Andrew Brown and firefighter Rannie Battle. “Stick to the list of names I gave you. Anybody who is trying to get in but whose name is not on the list has to step aside and wait until we see if there’s room.”

Washington felt a little uncomfortable. His instructions had the effect of preemptively divvying up the class by race, but there wasn’t really any other way to go about it. The Vulcans worked off the list of black applicants that their lawyers got from the city. Every one of the potential black candidates had gotten an e-mail from the Vulcans telling them about upcoming tutoring classes. Given the number of whites who’d started appearing in big groups, the Vulcans had to assume Merit Matters, or someone else, had gotten a copy of one of those e-mails and been busy forwarding it around. Some of the white applicants who started appearing at classes seemed genuinely perplexed about why they weren’t immediately allowed in. The Vulcans pegged them for candidates who were sincerely interested in the job. Others seemed fully clued in to a different agenda. They came to agitate for entry, even though they could care less about the actual class. The active-duty Vulcans even recognized a few of them and knew they were already firefighters. Washington was sure the white turnout was going to be even bigger in Queens than it had been in Harlem the other night, given that Jamaica bordered Long Island—home base for what seemed like three-fourths of the entire department and the bulk of its future candidates.

It promised to be a rowdy event. Washington wished he could be there—or better yet, he and Michael Marshall, a longtime Vulcan Society member known for his cool head. The current president of the Vulcan Society, John Coombs, was going to show up later, and there was no doubt he could hold his own if anyone tried to make trouble. He had a hard edge to him. Coombs, 46, grew up in Brooklyn. He became a plumber while still in high school, then worked his way through college doing temp jobs in banks and doubling as a security guard. He graduated with a marketing and communications degree, but made his money fixing pipes. Before long, he was a certified member of the Local 1 plumbers’ union. By the time he was 25, he was married with the first of four kids on the way. He only sidestepped into the FDNY thanks to a fortunate run-in with two Vulcan members in Brooklyn, who convinced him to take the test. He’d come on the job in 1999, and if anything, Coombs was even more outspoken than Washington. In tense situations where someone like Michael Marshall might try to smooth things over, Washington and Coombs were just as likely to throw a little more fuel on the fire.

As it happened, the NYPD got called to the Queens classroom at almost the same time Coombs arrived that night. White class takers started arriving early, about 100 of them. The Vulcan members hadn’t even gotten through the front doors to set up the lobby check-in spot when the school security guards were on them.

“You can’t be blocking the front entrance like this. All these people have got to wait outside in an orderly line,” one adamant guard insisted. The Vulcans rushed to set up their check-in stations and then open the doors, but they quickly lost control of the impatient crowd. Black candidates arrived and moved to the front of the line, where their names were checked off the Vulcans’ list. They passed into the classroom, while those stuck in the lobby got restless. Amid the flood of young students coming out of evening activities and parents trying to pick up kids, the disorganization threatened to spiral out of control.

“Are you with the FDNY? Are you a firefighter?” one of the white class takers said to a Vulcan who was trying to keep some peace among the angry group. “What company are you with?”

“Sir, please stand to the side over there. Your name is not on the list, but if there’s room once we’ve checked in all those who did sign up, we’ll let you in,” the firefighter answered.

“I did sign up and I got a confirmation, see?” the man responded, waving a slip of paper. “We all signed up and were told it was okay,” he said. “Why won’t you let us in? You’re letting in everyone else, why not us?”

“Sir, I don’t know where your confirmation e-mail is from, but it’s not from our group. You didn’t sign up with the Vulcans and we’re the ones running this class tonight, so as I said, you can wait and we’ll see if there’s space after everyone from our list is checked in,” the firefighter responded.

An angry din broke out as the Vulcans started shouting out the names of blacks on the list. The shoving mass of pissed-off men around the check-in table—more of a blockade than a line—linked arms, making it all but impossible for those called to get up front. Several parents and their kids, trying to get out the front door, got caught up in the tussle.

“This is a disaster,” the black firefighter thought to himself, just as the group of whites broke into a loud, off-key rendition of “We Shall Overcome.”

“I’m black Irish!” one of the white men shouted as the song petered out after a few rounds of the chorus. Another one yelled out that he would don “black face” if that would get him in the door.

When six school security guards came out to quell the noise, the crowd threw taunts at them.

“You’re too fat to be real cops,” one of the angry men jeered. Lieutenant Brown and firefighter Battle exchanged glances. This was getting too hot for them to handle. It was time to call the police to help disperse the men. Brown and Battle recognized several of the faces in the furious crowd. These were full-time firefighters, already on the job.

John Coombs, observing from the classroom, emerged in time to catch the white crowd shouting, “No justice, no peace!”

One of them, spying Coombs, shouldered his way to him.

“I got a right to go inside. I was told to come here,” the candidate declared.

“Oh, yeah? Who sent you? Who? I know it can’t be Merit Matters,” Coombs shot back. “That organization says we’re cheaters, that we can’t do anything the right way and have to look for special treatment, so I know that group can’t be sending you here to take a tutorial run by the Vulcans—that wouldn’t make sense, would it?” he snapped. “So who invited you here? Because it wasn’t us.”

Out on the street, red and blue lights flashed, and two NYPD patrol cars pulled up. They were followed by several TV vans, which immediately disgorged reporters and camera crews who switched on bright lights to record all the action. Only those students already in the classroom were allowed to stay. Everyone else was hustled out.

The next day, the newspapers and local media were full of reports from white firefighter candidates who claimed they’d been shut out of the Vulcan classes because of their race. The Vulcans had called only the names of black candidates but refused to let anyone else in, the group said.

“My dad [a firefighter] was killed on 9/11. I always wanted to be FDNY,” said a contender named Rob, 21, who was quoted by the New York Post.1

“What would Martin Luther King do?” another man, described as an “agitated applicant,” told the news cameras.2 A complaint was filed with the FDNY, asking the agency to investigate the legalities of the Vulcans’ actions. Two of the men who signed up online to take the Vulcan tutorial that night would later file complaints with the city’s human rights commission, alleging the white candidates were victims of reverse discrimination. They were represented by Merit Matters’s pro bono lawyers. School officials, frightened by what had happened and distressed to see their school in the press, told the Vulcans they were not welcome on the premises again.

Out in Utah on a ski trip, Michael Marshall struggled to hold his temper. It was unlike him to lose control of his emotions, especially anger. But as call after call came in from reporters looking for a little inside intel on what had gone down in Queens, he gained a better understanding of the picture that was being painted of the Vulcans, and his voice got heated.

“I wasn’t there, I’m on vacation. But I can tell you that whatever happened is a bunch of nonsense,” Marshall said for the umpteenth time, as a reporter from the popular news channel NY1 called him for comment. “We have never kept whites out of our classes, we don’t do that. That’s not what we are about. We’re here to help people, and in probably every class we’ve ever given some white candidates have showed up and we have let them in. This is just a stunt, a cheap, nonsense stunt,” he railed.

Marshall was no newcomer to the media game, having dealt with the New York press for more than ten years, but he had to tip his hat to Mannix for the canny way Merit Matters had set its narrative up—and how voraciously reporters were chasing it. It was quite a trick to make the black firefighters—with their paltry FDNY numbers—look like they were the ones causing a racial divide. Nobody in the Vulcan Society would deny that the organization’s main purpose was to get more blacks on the job—that was essentially why it was founded in 1941. But that unapologetic goal didn’t mean they also actively worked to keep other groups out of the FDNY—in fact, the opposite was true. The Vulcan Society had worked with the FDNY’s Hispanic Society in 1973 to file a legal challenge to the city’s written firefighter exam. The shared goal had been to get more Latinos and blacks into the ranks.

A federal judge agreed that the test was unfairly weeding out candidates of color and imposed a hiring quota on the city for four years. Between 1973 and 1977, for every three white firefighters hired, the FDNY had to pick one minority. That test became known as the 1-and-3 list because of it.

Not long after, in 1978, the FDNY opened its firefighter testing to women for the first time in its 117-year history. As far as the FDNY knew, its last female smoke eater had been a slave named Molly Williams. She’d belonged to a New York City merchant named Benjamin Aymar in 1818. The wealthy businessman liked to dabble as a volunteer firefighter at Oceanus Engine Co. 11 in Lower Manhattan, not far from where Zuccotti Park is today. Some say Williams also doubled as the firehouse cook, perhaps lent to the Engine Co. as Aymar’s chattel. Either way, Williams stepped up when a blizzard hit the city and an influenza bout wiped out most of the male volunteers. A fire alarm came in and she was the only one fit to respond. The sturdy slave, in her calico dress and checked apron, hauled the firehouse pumper through the swirling snow with as much strength and speed as any man, and thereafter became known as Volunteer No. 11, according to lore. After her, the FDNY wouldn’t see another woman firefighter for more than 150 years.

Confronted by a group of women determined to take the test in 1978, the FDNY changed its physical exam from a pass-fail to a scored one that an official later described as the toughest challenge the department had ever given. All 90 of the women who took it failed—exactly as the all-male department expected. Brenda Berkman, a young lawyer who wanted to join the FDNY, filed a historic lawsuit challenging the new test. She argued that the FDNY had chosen extremely difficult feats that had nothing to do with the actual job of firefighting—and the court agreed with her. A judge ruled that the FDNY violated federal law by creating a demanding physical test meant to keep women out of the firehouses. In 1982, Berkman and 41 other women joined the Bravest. But their ordeal wasn’t over. Berkman and another woman were told they flunked the Fire Academy and had to do it all over again, ostensibly because they needed extra training. When they graduated a second time they were fired, prompting another lawsuit. In 1983, after the judge found “extraordinary evidence of intentional discrimination,” they were reinstated. The fire commissioner at the time said that he dumped Berkman—who went on to serve for 25 years and retired in 2006 as a well-respected captain—because he was “convinced to a certainty” she could never control a pressurized hose line.3 Not a single fraternal organization in the FDNY supported the women in their quest—except the Vulcans. While the Uniformed Firefighters Association—the union of the rank and file—openly opposed accepting women firefighters, the Vulcans set up a “Godfather Program” to help train the women ahead of the physical test, and to act as mentors once they got in the firehouses.

Out in Utah, Marshall broke off the conversation with the reporter and hung up the phone. He was usually quick to see the humor in most things, and if his luxurious mustache bristled at all, it was in laughter rather than rage. But after 30 years of banging his head against the closed minds of the FDNY, the bitter irony of black firefighters being labeled racist left him too dispirited to laugh. It was never a problem for white chiefs to do a little extra to get their nephews and sons on the job, put in a word to get them a plum assignment or clear up a paperwork problem, but let a black firefighter try to help other blacks improve their odds, and the entire department was flooded with cries about special treatment.

He was 52, with more than 30 years as a smoke eater, yet Marshall hadn’t forgotten that he and most of his generation owed their FDNY careers to a lucky turn of fate—usually, a black firefighter already on the job who turned up at just the right time. Nobody from the FDNY was out recruiting back then, especially among minorities. He hadn’t grown up in a firefighting family and nobody in his Flatbush, Brooklyn, neighborhood had either. He’d never seen a single black firefighter on the engines that wailed past him and his friends as they crowded his block to play skelly, handball and stoop ball. His family was the first—and for a long time only—black household on his street, but that hadn’t affected his perception that he was living in a boyhood paradise. His mother, from Bermuda, was so light-skinned that she blended right into the all-white neighborhood. She stayed at home with the kids, while his African American dad made a decent living moving furniture. They owned no property and had no savings, but Marshall grew up with all the trappings of the middle class. A mischievous, high-spirited child—gifted with his mother’s agreeable charm and his father’s work ethic—he felt right at home among the Jewish, Italian and Irish kids who lived around him. It was the type of blue-collar, multicultural upbringing that many New Yorkers experienced, until the rapidly expanding highway system and white flight of the 1970s changed the landscape of the inner city and remapped the suburbs.

Marshall worked his way through junior high and parts of high school at the corner hardware store owned by a Jewish neighbor. He graduated from unloading trucks to waiting on customers and eventually to installing gates and locks. By the time he was 17, he had a steady gig as a locksmith on Flatbush Avenue. His reputation as a hard worker grew along with what would become his signature mustache, and by 18 he was a card-carrying member of Local 1888, the Harlem construction union, otherwise known as the black local.

For a few years Marshall thought he was doing all right, but then a rough patch took hold. The regular ups and downs of seasonal construction work turned into an eight-month drought. A friend told him the city was preparing a round of civil service tests. Feeling a little desperate, Marshall vowed to sign up for them all. He took the firefighter exam in 1977, the same year as the department’s first women firefighters. Even with the city wrung dry by its ongoing fiscal crisis, he saw long lines everywhere, for the NYPD and NY Transit cop tests, even the post office exam. If just one came through, he figured, he’d find his way into a better-paying and more stable job. With that, he had nothing to do but wait and hope, and watch his small pile of savings dry up. Then he got a much-needed phone call—not from the city, but from a construction buddy.

“Hey Mike, you working?” said the familiar voice of Frankie Abbondanza. Marshall met the older Italian guy on his first real construction job, building a pollution plant out on Wards Island. They’d remained close ever since.

“No, man, and I really need to. What you got?” Marshall said.

“Meet me on the corner of 31st Street and 31st Avenue in Astoria tomorrow morning, six o’clock,” Abbondanza said. “Bring your tools.”

By the early 1980s, Marshall was feeling flush. True to his name, Abbondanza steered him toward an abundance of work, and he’d been able to move out of his old apartment and find something roomier. At 26, Marshall was about to get married and start a family. He was earning decent pay now, but the worry of another long work lull with no income was always in his head. He found it odd that—four years later—he’d never heard back from any of the city jobs he applied for. One day, on a whim, he called a friend of his who had a regular 9-to-5 desk job, with access to a phone during business hours, and asked him to check with the city agencies to find out where he stood, starting with the fire department. The next day, he got some surprising news.

“Michael, the FDNY already passed your number,” his friend said, when Marshall reached him at home that evening. “You were 3,024, and they’re long past 3,000.”

“What? How is that possible? I never got a phone call, or a letter. Nobody told me anything,” Marshall said.

“Well, they’re past your number on the list, so they said you better get down to the investigation office on Pier A and see if you can still get in,” the friend said. Marshall hung up the phone, then picked it back up and called his construction boss to get the next day off.

On December 3, 1981, he hustled down to Pier A in Manhattan, and that’s where Lady Luck stepped in. After explaining his situation to the young man at the front desk, the clerk disappeared into a backroom. When he came out a few minutes later, an older black man in a firefighter’s uniform followed behind him, flipping through a manila folder.

“Michael Marshall, took the test in 1977, ranked number 3,024. Where you been? We’ve been looking for you. I sent you a letter six months ago,” the man said, fixing a stern brown eye on Marshall’s youthful face. Startled, Marshall tried to launch into an explanation of how he’d moved, but the man waved his words away.

“Don’t worry, I’ll take care of you,” he said, introducing himself as Henry Blake, firefighter and member of the Vulcan Society. “I’m part of the association of black firefighters, and when you get on the job, you can join and be one of us.”

In a development that must have helped many a young black candidate in the late 1970s, the fire department had appointed Blake as one of its background investigators. Many years later, with the advent of computers but also the uptick in attention to the racial disparity in FDNY hires, the department would bring in outside professionals to do its background checks. But for most of its history, firefighters carried out the task of looking into a candidate’s background to see if they were fit for the job or not. The investigators looked for arrest histories, especially felonies, truancy problems at school, dishonorable discharges from the military—anything that might suggest a faulty moral character or a history of trouble with authority. Of course, with spotty record keeping, no computers and an institutional tradition of taking care of one’s own, it was an easy matter for one candidate’s paperwork to get lost while another’s got pushed through. Or, in Marshall’s case, for Henry Blake to make sure his application got a speedy and favorable review.

For the next three weeks, anytime Blake called him demanding a piece of paperwork—a high school diploma, a driver’s license, even his birth certificate—Marshall took a day off to personally walk the papers down to Pier A and put them in Blake’s hands. As 1981 drew to a close, Blake was still waiting for Marshall’s fingerprint records to come back clean from the NYPD. The New Year came and went with no word, and Marshall resigned himself to more months of waiting. But just a week later, at 9:30 p.m. on January 8, Blake called him at home.

“Marshall, you need to show first thing tomorrow morning,” Blake said in his firm way, snapping out a Manhattan address. “Do not be late.”

“Did my fingerprints come back?” Marshall asked. There was silence on the other end of the phone.

“You let me handle that. Just be where I told you and on time,” Blake said.

When Marshall showed up at the address Blake gave him, he gaped in confusion at the crowd of about 250 people around him. Everyone was dressed in suits and ties, and he felt an itch of discomfort in his casual pants and shirt. A black firefighter approached him.

“How come you’re not dressed up?” he asked, introducing himself as John Tyson. His tone was friendly, but he wore a slight frown.

“I didn’t know we were getting sworn in,” Marshall protested, feeling abashed. He hadn’t told his parents or his fiancée or anyone, he realized, as a cheer went around the auditorium. But it was too late to worry about that now. Within a few weeks he was taking his probie classes at Randall’s Island, getting yelled at by red-faced fire officers and swearing back at them under his breath. He was one of just a few black firefighters training at the Rock, as Randall’s Island was called, but he had no problem finding friends among the mix of Italians, Jews, Irish and Latinos that made up the majority of his class. In a way, it was just like his childhood all over again, he told himself, as he huffed and sweated his way through firefighting drills and calisthenics.

Six weeks later, as Probationary Firefighter Marshall, he was assigned to Engine 221 in Williamsburg. His first day on the job, he and his crew had to respond to a massive explosion. A tanker along the industrial waterline blew to bits, a victim of the combustible fuel in its belly. As baptisms went, it was a doozy, and in the first seconds after the explosion Marshall—hanging out of the firehouse window—stayed where he was, eyes bugging at the size of the greasy black smoke ball erupting in the sky.

He was unceremoniously hauled out by the more experienced firefighters, and before he knew it, he was part of a team pulling a two-and-a-half-inch hand line out onto the jetty. The firefighters got as close to the river’s edge as they could and sprayed water everywhere, until the oil that oozed from the boat became a floating wall of flame headed right for them. Obeying orders, Marshall dropped the hand line and dove for the small space under the chain-link fence that kept out trespassers. It was the most expedient way out, and firefighters had cut a small hole through its bottom. They rolled under it one by one.

Marshall took to firefighting like any other young man with plenty of energy and a taste for adrenalin. He and the other rookie firefighters competed to see who could catch the most fire runs. Whenever he got a good one, he’d stand outside as the replacement shift rolled in and pantomime spraying a fire-hose nozzle.

“You caught one?” the other rookie would ask, a hint of envy in his voice. “What was it, tell me about it.” And when one of them got a chance to experience a real hot fire, they’d do the same to Marshall when he returned to the house for his shift.

It didn’t really matter to Marshall that he was the only black probie. For the most part, his new colleagues didn’t seem to care too much about it. Whether by happy chance or Henry Blake’s design, he’d gone to a company that had already housed at least seven black firefighters. The officers working with him had made the firehouse expectations clear: race didn’t matter, but a firefighter’s work ethic did. That was a motto Marshall could live by.

But the scarcity of blacks in general in the FDNY gnawed at him, and it was a frequent topic of conversation at the Vulcan meetings he now attended on a regular basis. True to his promise to Blake, he joined the fraternal organization as soon as he graduated from the Fire Academy, despite a few grumbles from some of the older white firefighters in his company. The lingering resentment from the Vulcans’ 1970s lawsuit still permeated the department, and the black firefighters who got along best with their crews were the ones like Marshall who avoided discussing anything related to race, quotas or FDNY hiring. Even so, the challenge of getting more blacks on the job was something Marshall embraced wholeheartedly.

It didn’t take long for him to learn that it wasn’t going to be easy. It wasn’t just one thing that kept blacks from joining the FDNY; there were many things, Marshall realized. The Vulcans had been trying through trial and error to bump up their numbers for nearly 60 years, and yet it remained a struggle to even get 500 blacks on the job at the same time. It wasn’t just that black candidates didn’t pass the entrance exam with high enough scores—it was that too few took it to begin with. And those who did get through often got washed out during the background check—the very place he nearly stumbled too. For every one black candidate who succeeded and got on the FDNY, there were several others, maybe even dozens, who could do the job but never even tried or got turned away by a technicality. The Vulcan system of having black firefighters do unofficial recruitment in the streets—approaching and talking to every young black male who looked reasonably fit—was like dropping tears into the ocean. It was never going to add enough diversity to the department to even make a visual difference, let alone get them any real kind of firehouse parity.

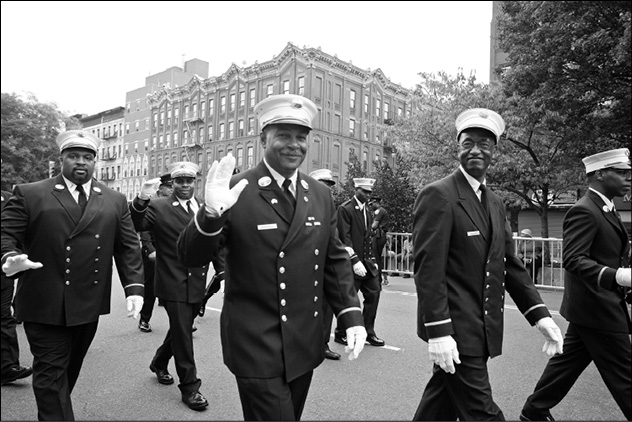

FDNY lieutenant Michael Marshall (center), Vulcan Society vice president and FDNY diversity advocate, with Lieutenant Clarence Mclean (r) and Lieutenant Duane Dewitt (l), September 2014. Photo credit: Michel Friang.

Marshall needed someone in the Vulcans who would be willing to join with him to do whatever was necessary to force the FDNY toward real change—and that would require new blood. After a decade of firehouse bickering and battling over the court-imposed quota system in the 1970s, followed by a fresh wave of vitriol over the addition of women in the 1980s, few among the Vulcan leadership had the stomach for another protracted fight. The past 20 years had been exceptionally draining for everyone, fraught with racial and economic disasters and an acrimonious union strike in 1973. Called by the Uniformed Firefighters Association that represented the city’s firefighters, the strike only lasted five and a half hours. But the damage it caused stayed around much longer. Many of the black firefighters refused to go along with the walkout, arguing that their inner-city neighborhoods were the ones most at risk. White firefighters also expressed disgust at the prospect of picketing outside their own firehouses, but many felt compelled to give at least a token show of compliance out of union solidarity. Some found a way to back the UFA, but also square their firefighting conscience: they manned the picket lines outside, but ran into the firehouse periodically to make sure they weren’t missing any alarms. The union got lucky and no major disasters occurred to test their members’ loyalty during the short work stoppage. Not long after the divisive strike, which the union president said his membership voted in favor of, it was discovered that he had falsified those results to force a walkout. The strike never should have happened. It was a hardball move devised by the union head to get a better contract for his members. His rash action imperiled public safety, poisoned the union’s relationship with the city and added a bit more depth to the racial rifts already running through some firehouses.

The Vulcans needed to rebuild, financially and in other ways too. Marshall understood that at some point the group would be ready for more, and he would be as well. Six full and happy years later, he was an experienced hand at firefighting and the father of six-year-old twins, Michael Jr. and Melinda. He was also taking on a more active role as a Vulcan mentor to new black probies. That spring, the FDNY finished off its prior list with a final round of hiring and several more black candidates who made the cut got their chance to prove themselves in the Fire Academy. Marshall got the phone numbers of all the new black firefighters and he called them up to invite them to the annual African American Day Parade. The Vulcans had been marching in it for decades and, since 1971, usually accompanied by a charismatic young congressman from Harlem named Charles Rangel.

Marshall had met most of the new probies at Randall’s Island already, so when he saw one tall young man, skinny as a pipe cleaner and wearing a spotless FDNY-issued blue work shirt, he recognized him right away. Paul Washington, probationary firefighter in the July class of 1988.

“Hey brother, good to see you. Glad you came out. You get your assignment yet?” he said, sticking out his hand. The younger man took it.

“Yeah, I’m headed to Engine 7, Manhattan,” Washington replied, giving Marshall a hard shake in return. Neither knew it at the time, but it was the beginning of a revolutionary new partnership.