FIVE

THE KIM DYNASTY AND PYONGYANG’S POWER ELITES

Who Was General Kim Il Sung?

On October 14, 1945, Pyongyang citizens got their first glimpse of Kim Il Sung, future Great Leader and founder of the DPRK. As he mounted the podium at the Pyongyang Citizens’ Welcoming Masses rally, the audience was expecting someone a lot older and more experienced. Instead, a nervous thirty-three-year-old read from a prepared text.

“Imperial Japan, which crushed us for thirty-six years, has been destroyed by the heroic struggles of the Red Army,” Kim remarked, and called on all Koreans to “pool our strength to create a new democratic Joseon [Korea].”1 A contemporary account, despite the rhetoric, provides a very unflattering image of Kim.

They saw a young man of about 30 with a manuscript approaching the microphone. He was about 166 or 167 centimeters in height, of medium weight, and wore a blue suit that was a bit too small for him. His complexion was slightly dark and he had a haircut like a Chinese waiter. His hair at the forehead was about an inch long, reminding one of a lightweight boxing champion. “He is fake!” All of the people gathered upon the athletic field felt an electrifying sense of distrust, disappointment, discontent, and anger.2

Unaccustomed to speaking before a large crowd, Kim sounded stilted, and “the people at this point completely lost their respect and hope for General Kim Il Sung.”3 Making matters worse, Kim was preceded by Cho Man-sik, a major nationalist leader who gave a rapturous thirty-minute speech—even dropping his eyeglasses at one point because he was so energized—so the audience was even more disappointed by Kim. When the audience began to vocalize their disenchantment, however, a Red Army soldier fired off an empty round. Only then did the crowd fall into line.

Three years after this inauspicious start, however, Kim Il Sung would become North Korea’s leader. Two years after that, in June 1950, he unleashed a fratricidal war. Betting that the Americans, who had withdrawn their military forces from South Korea in 1949, wouldn’t come to Seoul’s defense, Kim’s blitzkrieg worked brilliantly until he was cut off by General Douglas MacArthur. North Korea was saved from total defeat only with the help of the PRC.

No communist country since the formation of the Soviet Union in 1917 has been led by a family-run dynasty, with two exceptions: North Korea and Cuba. Raúl Castro succeeded his brother Fidel after Fidel stepped down as president due to failing health in July 2006. Fidel subsequently resigned from the Communist Party Central Committee in April 2011. None of their children were trained to succeed them.

Importantly, Fidel and Raúl were contemporaries in the Cuban Revolution, which brought down the Batista regime in 1959. As of this writing, the eighty-seven-year-old Raúl remains First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba but stepped down as president in April 2018. Although the Castros have dominated Cuban politics since 1959, they never built a grotesque personality cult like exists in North Korea under the Kims.

Nicolae Ceaușescu, who ruled Romania from 1965 to 1989, came close to forming a dynasty when he shared power with his wife, Elena. As the Eastern bloc began to crumble, the people turned on Ceaușescu. He and his wife were arrested, tried by a military tribunal, convicted, and shot in December 1989. In today’s North Korea, however, it’s impossible to imagine a similar situation in which thousands of citizens call for Kim Jong Un’s ouster.

The seeds of the North Korean police state were planted and nurtured by the Soviet Union, but Kim Il Sung outdid his Soviet handlers: he created the world’s most ruthless dictatorship and set up a family dynasty that has ruled North Korea for seventy years. This is the story of how the dynasty was founded and how it is sustained.

Planting Moscow’s Man in Pyongyang

Kim Il Sung was born in 1912 as Kim Song Ju. His mother, Kang Ban Sok, was active in the Presbyterian church. The family later fled to Manchuria from their hometown not far from Pyongyang due to worsening economic conditions and the oppressive nature of Japanese rule. His father was Kim Hyong Jik, who was educated at Pyongyang’s Sunwha and Sungshil schools, founded by American missionaries. American missionary Nelson Bell, whose son-in-law was the famous evangelist Billy Graham, introduced Kim Il Sung’s parents to each other.4 Perhaps owing to this very unique connection (although neither Kim Il Sung nor North Korean sources have ever admitted it), Graham twice visited North Korea and met with Kim Il Sung in 1992 and 1994.5

A CIA assessment of Kim Il Sung (prepared in 1949) claimed that while still in high school he murdered a classmate and another person for money, and at the age of eighteen he became a member of the Chinese Communist Youth Group.6 He first joined the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1930 and subsequently became a member of the Northeast Anti-Japanese Army under the CPC in 1935.7 The CIA assessment noted that “in 1938, Kim was made commander of the Second Army of the [Chinese Communist Forces] to fight the Japanese, and in 1942 he was made a high official of the CPC. Kim was known for his brutality even among his Chinese comrades, and by the late fall of 1942 all but five of his followers left him.”8

As more Russian archival materials have come to light, historians continue to study how Moscow ultimately chose Kim Il Sung as their point man in Pyongyang. For instance, North Korea experts such as Andrei Lankov based in Seoul argue that initial U.S. intelligence estimates that explained Russia’s master plan on the Korean Peninsula were somewhat exaggerated.9 However, according to Soviet reports on communism in Korea in 1945, there is little doubt that Moscow had its eyes on Kim Il Sung and the creation of a pro-Soviet regime from the outset.

In a cable sent to the main political directorate of the Red Army in 1945, Soviet officers noted that “The name of Kim Il Sung is known in broad sections of the Korean people. He is known as a fighter and hero of the Korean people against Japanese imperialism. The Korean people have created many legends about him, and he has indeed become a legendary hero of the Korean people. The Japanese used any means to catch Kim Il Sung and offered a large sum of money for his head.” Furthermore, the report stated that “Kim Il Sung is popular among all democratic sections of the population, especially among the peasants. Kim Il Sung is a suitable candidate in a future Korean government. With the creation of a popular democratic front, Kim Il Sung will be a suitable candidate to head it.”10

Yu Seong-cheol, a Korean War veteran who was an officer in the KPA nursing corps, first met Kim Il Sung in September 1943 not far from Khabarovsk, where Kim’s 88th Special Independent Strike Brigade was based. “Comrade, do you speak Korean?” asked Kim Il Sung, and when Yu replied she did, he said, “That’s good. Come work for me as my Russian translator.”11 Fluent in Chinese, Kim spoke only passable Russian.

Kim headed a battalion of about two hundred Korean soldiers in the 88th Brigade, which included Soviets, Chinese, and Koreans. The main goal of the 88th Brigade was to infiltrate Japanese-held areas and retrieve intelligence. The Soviets wanted to use the brigade as a bridgehead to help set up communist regimes in China and Korea once the Japanese surrendered. “Unlike today [1991], Kim was physically weak and I never saw him lead a reconnaissance mission,” recalled Yu, “but he was regarded as someone with a sharp mind with leadership skills, and that’s why he captured the Soviets’ attention.”12

Soviet support for Kim was the reason that several years later he would be able to beat out both the Yenan faction (those who fought with the CPC) and the Soviet faction (Korean communists trained in the Soviet Union) to take control of the new North Korean state in 1948. Yet this basic historical fact has been completely erased from official state history. North Koreans are taught that, much as Moses led the Jews when they were expelled from Egypt, Kim Il Sung liberated North Koreans from Imperial Japan. According to the myth, it was Kim Il Sung’s absolute military genius that defeated Japan on the Korean Peninsula; never mind that, in reality, he led only two hundred soldiers toward the end of World War II.

As the history given here shows, the foundations of North Korea’s political, economic, and military systems were laid down by the Soviet Union. But recognizing this is anathema to the mythology of the Kim family. In that mythology, only Kim Il Sung emerged to save the Korean people from the yoke of Japanese colonialism—even though the truth is that he played just a very minor role in the anti-Japanese struggle.

As Japan neared defeat in the spring of 1945, Moscow turned its attention to Korea—a small but geopolitically vital piece of real estate. At the time Seoul, rather than Pyongyang, was the epicenter of Korea’s communist activity, and it was here that the Korean Communist Party (KCP) was based when Korea was liberated from Japan in August 1945.13

When Japan surrendered unconditionally on August 15, the United States’ primary preoccupation was ensuring that the Soviets wouldn’t have a hand in controlling postwar Japan. The Soviet Union had declared war against Japan on August 8—a week before Japan’s surrender—and immediately its troops crossed into northern Korea. Washington became concerned that the Red Army would occupy the entire peninsula.

Despite the wishes of Koreans for immediate independence, the peninsula was divided into Soviet and American zones along the 38th parallel. Two American colonels—Dean Rusk, who later became secretary of state, and Charles Bonesteel, who went on to become commander of the U.S. Forces Korea—were ordered to figure out where to place the American zone of occupation.

As they huddled in an office in the War Department in Washington, they found a copy of National Geographic that had a map of Korea. “Working in haste and under great pressure, we had a formidable task: to pick a zone for the American occupation,” wrote Rusk. “Neither Tic [Bonesteel] nor I was a Korea expert, but it seemed to us that Seoul, the capital, should be in the American sector.”14 Rusk and Bonesteel were amazed that their superiors “accepted it without too much haggling, and surprisingly, so did the Soviets.”15

Little did they know that their decision would have longer-term consequences. Rusk subsequently stated that they would have chosen another demarcation line had he been aware of the historical importance of the 38th parallel. In 1896, as Russo-Japanese ties worsened over Korea, Japan proposed to divide the peninsula along the 38th parallel into Russian and Japanese spheres of influence, a proposal that Russia rejected.16 In 1903 the Russians proposed a similar idea, with the dividing line along the 39th parallel, but it was rejected by the Japanese.17

General Douglas MacArthur, who headed the Allied forces based in Tokyo, dispatched Lieutenant General John R. Hodge to administer the southern zone, while Colonel General Terentii Fomich Shtykov, under whom Kim had received his political training, became the head of the Soviet occupation zone. “For all practical purposes [Shtykov] was the supreme ruler of North Korea in everything but name,” according to Andrei Lankov, and “it was under his tutelage that Kim Il-sung’s system was born.”18

Despite the propaganda that fraternal Soviet soldiers liberated Korea, the reality was that the Red Army pillaged and raped its way to Pyongyang. Once there, the Soviets didn’t waste any time in setting up a communist system in northern Korea. Stalin ordered the creation of a “wide-ranging bourgeois democratic regime” in September 1945—as soon as his forces had occupied the region north of the 38th parallel. The Soviets created administrative units in all five provinces in northern Korea, disarmed all resistance groups and fighters, and ordered all “anti-Japanese parties and organizations” to register with the Russian authorities.19

Subsequently the Soviet authorities opted to form the Korean Communist Party North Korea Bureau—ostensibly in order to facilitate operations, but in reality Moscow wanted it to be entirely separate from the existing KCP. In December 1945, the KCP North Korea Bureau elected Kim Il Sung as First Secretary. He immediately lashed out at his opponents. Because it was essential for Kim Il Sung and his Soviet backers to create a new political entity that could rival the indigenous communist party based in Seoul, a comprehensive propaganda campaign was launched to undermine the KCP in Seoul and eliminate all organizational linkages between the existing communist party and the new communist party under Kim Il Sung’s leadership. “After organizing the North Korea Bureau, nothing was done from October to December,” Kim wrote, and “the third enlarged conference was convened because of the infiltration by undesirable and jealous elements who began operations to dismember the bureau and party leaders who just looked to Seoul for directions.”20 In practical terms, this meant that all of the northern provinces were now under the direct control of the KCP North Korea Bureau and, by extension, Kim Il Sung.

The nascent U.S. Central Intelligence Agency wrote in November 1947 that “Soviet tactics in Korea have clearly demonstrated that the USSR is intent on securing all of Korea as a satellite” and that “details of an alleged Soviet ‘Master Plan for Korea’ were compromised in mid-1946, and subsequent events tend to confirm the fact that the USSR has been following the essential outline of this ‘Plan’ with minor divergences necessitated by tactical considerations.”21

In a March 1948 assessment, the agency warned that the absorption of Korea into the Soviet orbit would have serious consequences, such as “adverse political and psychological impact throughout the already unstable Far East, particularly in China, Japan, and the Philippines; which would increase in direct proportion to the investment made by the US in Korea prior to any surrenders of that country to Soviet domination.”22 A more chilling analysis was made by the CIA in February 1949 on the consequences of U.S. troop withdrawal from South Korea:

Withdrawal of US forces from Korea in the spring of 1949 would probably in time be followed by an invasion, timed to coincide with Communist-led South Korean revolts, by the North Korean People’s Army possibly assisted by small battle-trained units from Communist Manchuria. Although it can be presumed that South Korean security forces will eventually develop sufficient strength to resist such an invasion, they will not have achieved that capability by the spring of 1949. It is unlikely that such strength will be achieved before January 1950.23

Yet despite such warnings, the United States withdrew its forces from South Korea at the end of 1949. South Korea’s own armed forces were no match for North Korea’s military, which was trained and armed by the Soviet Union.

In January 1950, six months prior to the outbreak of war on the Korean Peninsula, U.S. secretary of state Dean Acheson remarked in a speech at the National Press Club that the U.S. defense perimeter in the Far East didn’t include South Korea. For Kim Il Sung, this seemed to be a green light signaling that the United States wouldn’t intervene if the South was attacked. The irony, of course, is that while U.S. intelligence correctly assessed that the communization of the peninsula would have negative consequences for U.S. interests in the Far East, until the outbreak of war in June 1950 the administration of President Truman didn’t believe that South Korea was important enough to warrant serious attention.

The Korean War and the Making of a Living God

At 8 p.m. on March 5, 1949, six months after he became North Korea’s leader, Kim Il Sung led a North Korean delegation to meet with Stalin. The Soviet leader agreed to most of Kim’s requests for economic and technological assistance, though Kim’s real objective was to get approval for an invasion of South Korea. But events elsewhere were more pressing—the Berlin blockade was ongoing, tensions with the United States were intensifying, and the Kremlin faced the enormous task of rebuilding the war-torn USSR—so Stalin told Kim to be patient. Although the Soviet Union would be withdrawing its forces from North Korea, Stalin promised to provide military aid—airplanes, automobiles, and other equipment and assistance worth about 200 million rubles (roughly $40 million).24

By the end of 1949, however, two developments pushed Stalin to give a thumbs-up to Kim Il Sung’s plan to invade the South: the successful testing of the Soviet Union’s first atomic bomb in August 1949 and the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in October 1949. If the United States did indeed respond to a North Korean invasion of the South, it would now face the specter of a united communist front.

Kim also sought assistance from China even before the official founding of the PRC. Soviet specialists in northeastern China cabled Moscow in May 1949 to inform their comrades of Mao’s meeting with Kim and North Korea’s intention to invade the South. “Comrade Mao Zedong said that such aid [military personnel and weapons] would be granted,” the report said. Further, Mao told Kim that “we have also trained 200 officers who are undergoing additional training right now and in a month they can be sent to North Korea.”25 By early 1950, Kim Il Sung was ready for war.

Six days before North Korean forces invaded South Korea, the CIA wrote an estimate of the North Korean regime’s capabilities. The DPRK, the report noted, was in firm control but also totally dependent upon the Soviet Union for its existence.26 North Korea was increasing its “program of propaganda, infiltration, sabotage, subversion, and guerrilla operations against southern Korea,” but the strength of anti-communist sentiments in the South meant that such actions alone wouldn’t succeed in breaking South Korea.27 An attempt by the communists to control the entire peninsula would likely be deterred by South Korean troops’ willingness to resist and the lack of popular support for the communist regime in the South. That said, however, the estimate emphasized that although the northern and southern forces were nearly equal in terms of combat effectiveness, training, and leadership, the northern Koreans possessed a superiority in armor, heavy artillery, and aircraft. Thus, northern Korea’s armed forces, even as constituted and supported, had the capability to attain limited objectives in short-term military operations against southern Korea, including the capture of Seoul.28

Kim’s blitzkrieg strategy saw initial success because the South Korean military didn’t have the mechanized forces, long-range artillery, or combat aircraft needed to hold off Kim’s onslaught. However, Kim miscalculated on two counts: his belief that the United States wouldn’t defend the ROK and his perception that pro-communist forces in South Korea would rise up against the “puppet regime” the moment North Korea attacked.

Nevertheless, in the Kim mythology, it is impossible for the Great Leader to have made any mistakes. So the only explanation for the war’s disastrous outcome was that Kim must have been duped by counterrevolutionaries and American spies. Conveniently for Kim, he could choose to purge whomever he wanted to. Major figures such as Ho Kai—sent by the Soviets to North Korea and the person who controlled all party affairs—were charged and tried by a kangaroo court and executed. Hundreds of military officers and party officials were purged or executed for losing the war.

As the postwar purges began in earnest, Kim was faced with a startling development in the Soviet Union: de-Stalinization by Nikita Khrushchev beginning in February 1956. “Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation, and patient cooperation with people,” Khrushchev said in a speech, “but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion.”29 Using words that no Soviet would have dared utter when Stalin was alive, Khrushchev went on, “Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position—was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation.”30

For Kim Il Sung, this was abject heresy. If the most powerful communist country in the world could bring down the very man who had installed Kim, then how secure could he be? What would his enemies in North Korea think? Wouldn’t they be encouraged to oust him?

Another part of Khrushchev’s speech said:

It is clear that here Stalin showed in a whole series of cases his intolerance, his brutality, and his abuse of power. Instead of proving his political correctness and mobilizing the masses, he often chose the path of repression and physical annihilation, not only against actual enemies, but also against individuals who had not committed any crimes against the party and the Soviet Government.31

If one changes “Stalin” to “Kim” and “Soviet” to “Korean,” these words would be equally applicable to Kim Il Sung’s North Korea.

Kim immediately realized that such revisionism must be rooted out in the North before it could appear on the surface—much like in the movie Minority Report, where someone can be arrested for a “pre-crime.” Kim also understood that his legacy could be guaranteed only by building his own brand of communism, independent from Marxism-Leninism, and by grooming his son Kim Jong Il to succeed him.

By 1964, when Kim Jong Il graduated from Kim Il Sung University—with the highest grades ever given to a student, and where professors said they learned pathbreaking lessons from him—the stage was set for two forces to begin converging toward the establishment of the world’s first truly Orwellian state. First, Kim Il Sung paved the way for Kim Jong Il to oust his own brother, Kim Yong Ju, who had been seen until then as Kim’s successor. Second, in the mid-1960s, Hwang Jang Yop, North Korea’s premier political ideologist and head of Kim Il Sung University, began to develop Juche as an indigenous form of socialism. In 1972 Juche became official political ideology, and very quickly it was turned into an instrument for glorifying the Great Leader.

Hwang later defected to South Korea and wrote critically about Juche. “What maintains the North Korean system?” wrote Hwang. “Juche has become a tool to enslave the North Korean people … and the myth of absolutism surrounding Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il is based on the so-called revolutionary history based on a fabrication of lies and exaggerations and the ideological justification for worshipping the two Great Leaders.”32

“Kim Jong Il believes that the people are his possession,” Hwang continued. “Regardless of the crimes a Great Leader commits, it is not thought of as a crime. There isn’t a notion of trampling on human rights. Because in North Korea, the most important objective of the people is pledging absolute loyalty in mind and body to the Great Leader.”33

Each place that Kim Il Sung (and subsequently Kim Jong Il) visited became a sacred site. A park bench where Kim Il Sung once sat is encased in glass. A giant statue of Kim Il Sung with his right arm stretched toward the masses overlooks Pyongyang. A student’s desk remains empty save for a fresh flower to memorialize the moment the Great Leader sat in the chair to offer on-the-spot guidance. His birthplace, Mangyongdae, is the mecca of North Korea. All North Koreans are urged to visit the site and pay their respects, as are foreign visitors.

But in March 2011 the impossible happened. A twenty-four-year-old physics major at Kim Il Sung University became sick of his professors and student leaders routinely demanding payoffs. Plus he had to find a way to pay for his tuition. He decided to defect to South Korea but had heard that if he brought across with him an artifact stolen from Mangyongdae, he would become a rich man. While almost everything in Kim’s birthplace was a replica or a reconstruction, he found out that one small door had remained unchanged. By paying bribes and exploiting security blind spots, he managed to steal the door.

Caught during a routine inspection two weeks later as he was planning to board a ship transporting coal from Haeju to the Chinese coastal city of Dalian, he was handed over to the Ministry of State Security. He was subsequently executed—and so were three generations of his family.34 Furthermore, Kim Jong Il was livid that such an outrageous crime hadn’t been prevented, and numerous security officials were removed from their posts.

How long North Korea can sustain the mythology of the Kim dynasty remains unclear. No one really believes in it anymore. But North Koreans continue to adhere to it, at least on the surface, partly out of fear. In addition, it’s also partly due to the twisted logic of preserving the racial purity of North Koreans through ethnic cleansing, otherwise known as “liberating” the genetically and spiritually “tainted” Koreans in the South.

Big Brother’s Keepers

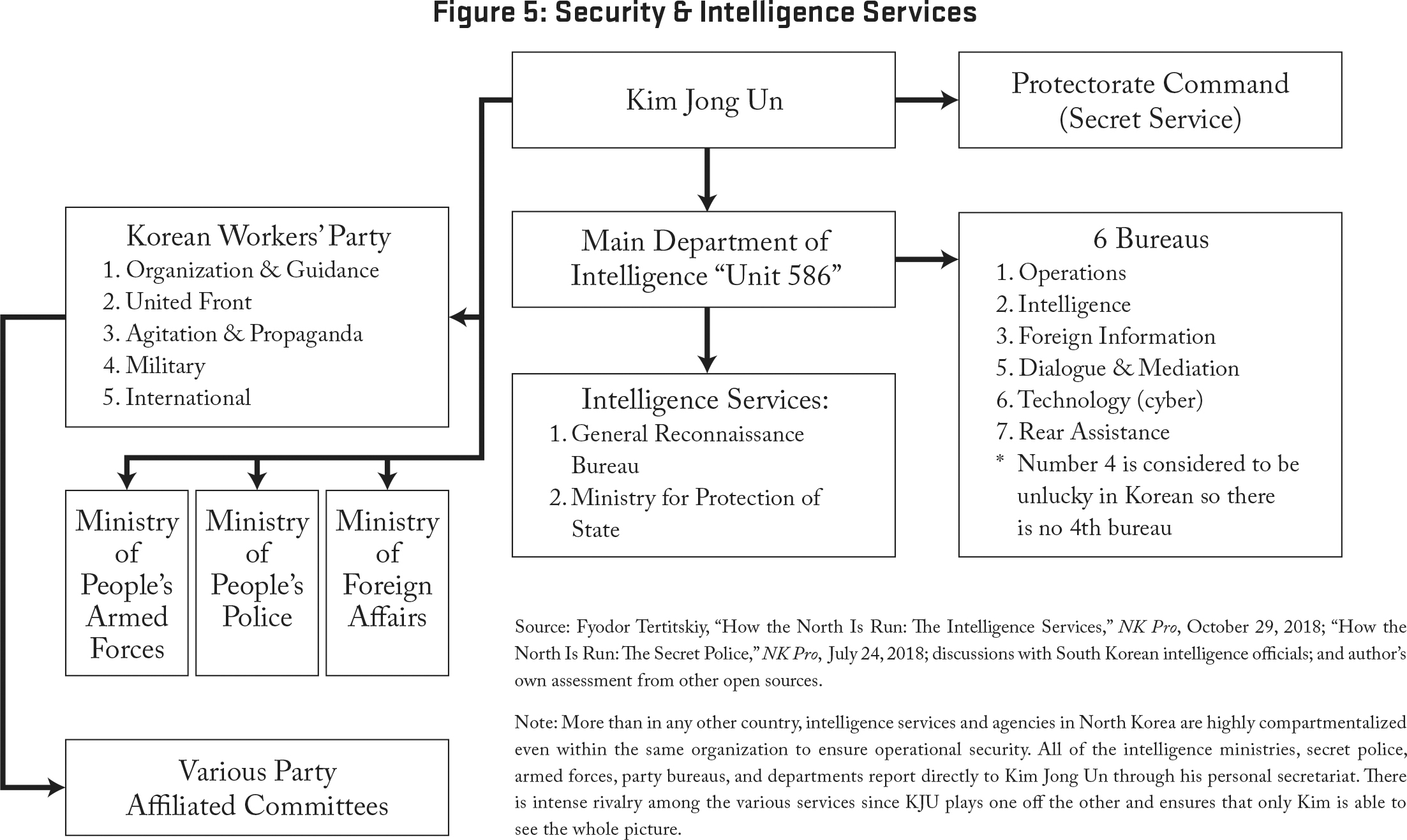

One of the most searing images of North Korea is phalanxes of perfectly aligned goose-stepping soldiers taking part in the world’s largest military parades. As the soldiers pass by the Great Hall of the People and the Supreme Leader, all of them turn their heads upward and to the right, acknowledging Kim, at exactly the same time.35 And while such images convey the impression that the party, the military, and the security forces all function like a well-oiled machine, looks can be deceiving. Because while they are very efficient at certain things—carrying out Kim Jong Un’s orders, recruiting the best and the brightest, and maintaining control over the masses—the triad is also corrupt to the core.

Especially during the Kim Jong Il era, intense competition and rivalries between contending centers of power were encouraged, in part to divert the elites’ attention away from the disastrous famine that was literally killing hundreds of thousands of North Koreans. One major side effect of this internecine competition was the explosion of corruption at all levels of governance. Because virtually no North Korean officials in the party or the government live on their wages, kickbacks are routine and pervasive. As jangmadang and the donju gain increasing influence, party and government officials have to compete against each other to get bigger cuts of the kickback pie. Knowing the up-and-coming donju, for example, means that critical intelligence is a major asset in preserving your illicit income stream, which feeds competition between officials.

As illicit hard-currency earnings—from actions such as counterfeiting, selling arms, drug trafficking, and sending slave laborers overseas—began to fluctuate in the late 1990s due to tighter international sanctions, Kim Jong Il resorted to squeezing the party and military elites, forcing them to double their hard-currency earnings. In turn, this meant that the class immediately below them was also tasked with achieving specific annual hard-currency quotas that could be funneled up the structure, as was the class below them, and so on down the line.

Anti-corruption campaigns have been launched but with little effect. Kim Jong Il periodically made examples of the greediest officials by demoting them, sending them to reeducation camps or gulags, and even executing some, and Kim Jong Un has followed suit. In the end, however, Kim Jong Un cannot stop the corruption. The Kim dynasty made a Faustian bargain with North Korea’s super-elites—much as the Saudi ruling family did with the Wahhabi sect, one of the most fundamentalist branches of Islam. The leadership and the elites keep each other alive through a web of incentives and a sharing of the spoils. Kim Jong Un cannot cut off the arm that feeds him.

Pyongyang’s Power Elites

During Kim Jong Il’s reign, North Korea’s primary aim was gangseong daeguk, or a powerful and prosperous country; it became the goal of Kim’s military-first policy. The policy was first promulgated in 1998, and throughout the early 2000s the propaganda machinery churned out numerous studies attributed to Kim Jong Il, such as Military-First Policy (2000), The Great Leader Comrade Kim Jong Il’s Unique Thoughts on Military-First Revolution (2002), and The Glorious Military-First Era (2005), among many others. Of course, Kim didn’t pen a single word himself, but these works were written to justify why the bulk of the country’s already dwindling resources had to be shifted into the military sector. The responsibility for carrying out this policy fell to the National Defense Commission (NDC), the most powerful organ in Kim Jong Il’s North Korea; Kim served as the commission’s First Chairman.

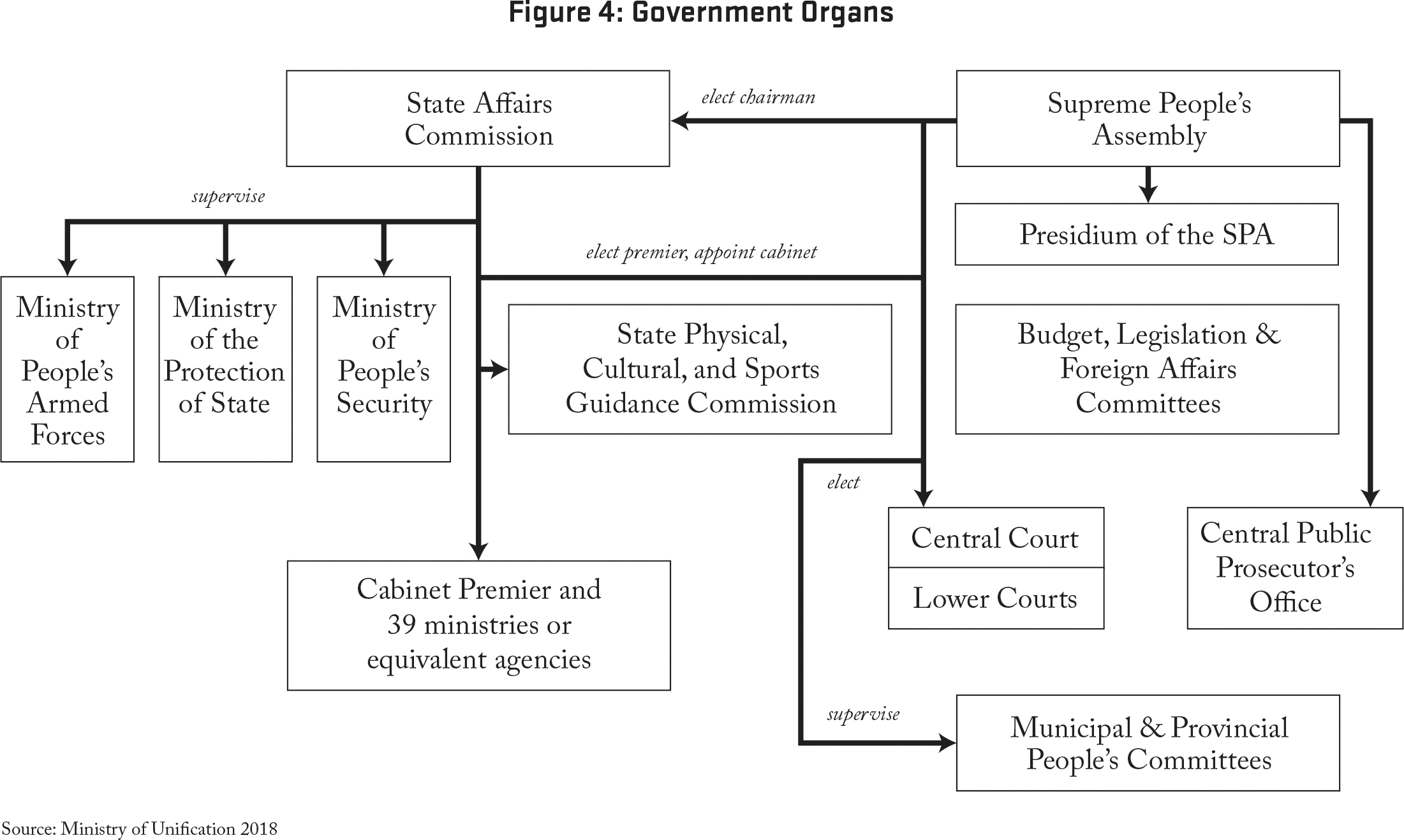

When Kim Jong Il died in 2011, he was posthumously elevated to the position of Eternal Chairman of the NDC. Kim Jong Un assumed the title of First Chairman of the NDC.36 However, in June 2016 Kim Jong Un opted to create a new highest decision-making body, the State Affairs Commission (SAC). The establishment of the SAC was Kim Jong Un’s way of differentiating his rule from his father’s. He has consolidated power and put into place his own cadre of loyalists throughout the party, the KPA, the security apparatus, and the cabinet. Unsurprisingly, Kim has opted for a divide-and-rule strategy. For example, Kim initially appointed General Kim Won Hong as head of the Ministry of the Protection of State (still widely referred to in the West by its former name, the Ministry of State Security [MSS]), a post that had been vacant for twenty-five years. In January 2017, the general was demoted to major general and his core lieutenants were executed for high crimes.37 And while under Kim the SAC replaced the NDC as the most powerful decision-making body in North Korea, and the Presidium of the Politburo is the highest-ranking office in the party, it’s difficult to imagine any real give-and-take between Kim Jong Un and members of the Politburo. Still, the party is a unique organization, since it is so pervasive; key party departments, such as organization and guidance, propaganda and agitation, cadres, and general affairs, have much more influence than their titles suggest.

As noted in previous chapters, Office 39, in charge of all hard-currency operations and holdings, is the most important unit in the secretariat, or Kim Jong Un’s main office. Here one can see a contrast to China: although China’s Xi Jinping has consolidated more power than any other leader since Deng Xiaoping, collective leadership has been merely weakened, not completely discarded. No such collective leadership ever existed in North Korea except during its earliest days (1948–1950), and even then Kim Il Sung was always the most powerful figure.

“All of the critical personnel changes made by Kim Jong Un have been based on absolute loyalty, preservation of Juche ideology and Kim Il Sung / Kim Jong Il Thought, and the strengthening and consolidation of his power,” according to an assessment made by the Institute for National Security Strategy, a think tank under South Korea’s NIS.38 During Kim Jong Il’s era, the military-first policy meant that the KPA received greater attention than the KWP, much to the consternation of party leaders. The National Defense Commission was the highest decision-making body under Kim Jong Il, but, as noted earlier, Kim Jong Un abolished it and replaced it with the SAC. Even before he eliminated the NDC, its power was reduced: during his first year in power, 2011–2012, the NDC had sixteen members, but by 2016, the number had been reduced to eleven.39

North Korea’s dictatorship is unique both in its longevity and in the absolute concentration of power in the top leader. This doesn’t mean that Kim decides everything himself; that would be impossible. Still, no policy or directive can be implemented without his approval. Under Kim, the party has gained the upper hand, and political commissars throughout the KPA relay the party’s orders.

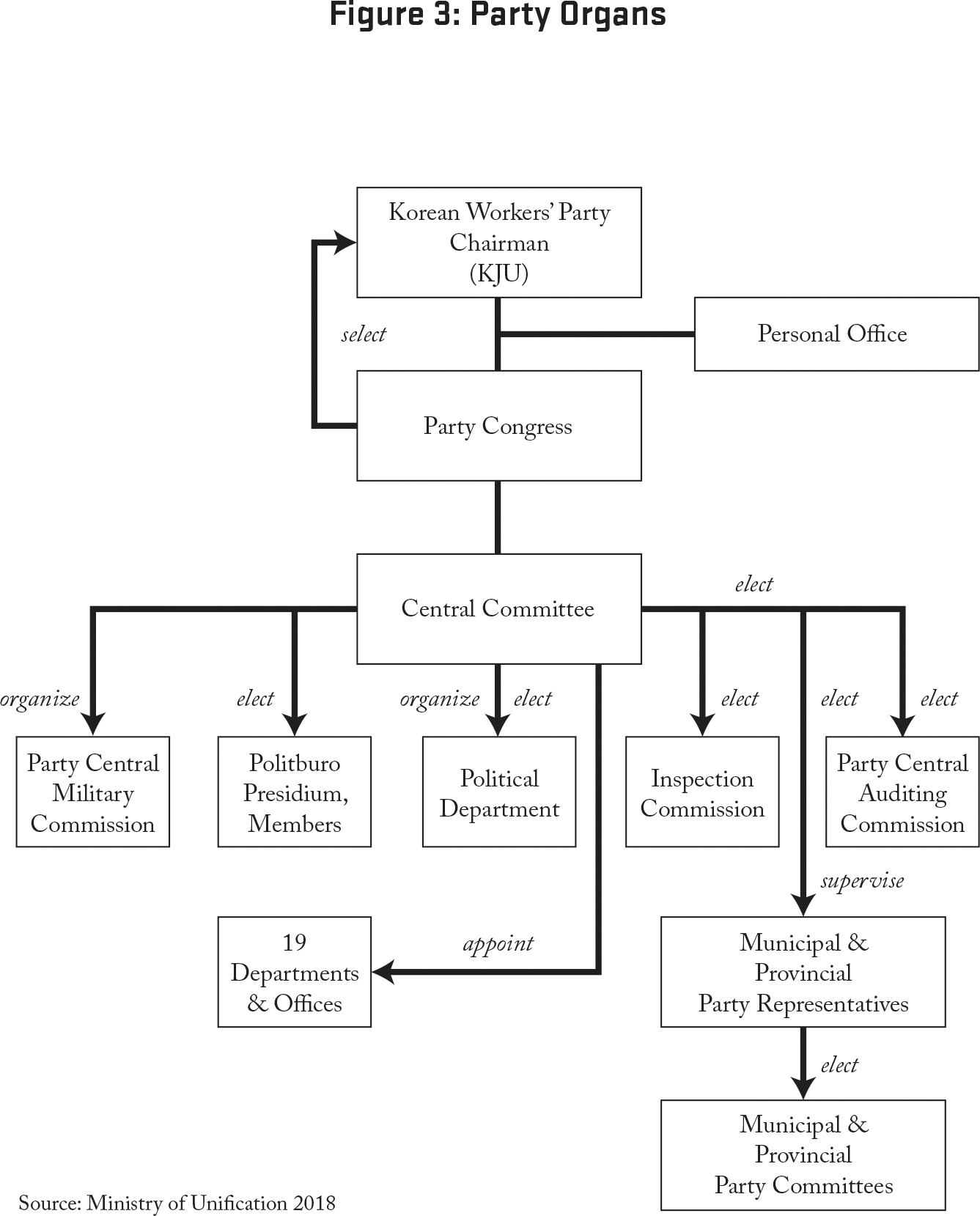

Pyongyang’s highest elites are those that are in charge or have important roles in the party, security apparatuses, the KPA, government, and state-run import-export companies or those charged with specific hard-currency earnings (see figures 3,4,5). They include the top 5 percent of the core class, ministers or officeholders with ministerial rank, and Kim’s inner circle: members of the SAC, the Central Military Commission of the KWP, and the Main Department of Intelligence.

In April 2019, Kim Jong Un undertook the most extensive leadership change since he assumed power. Longtime confidant Choe Ryong Hae was named the nominal head of state, or president of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA), replacing Kim Yong Nam, who had held that post for over twenty years. Kim also named Kim Jae Ryong as the new prime minister, replacing Pak Pong Ju, who was moved to vice chairman in charge of economics at the central committee of the KWP.40 Pak Pong Ju is also a member of the standing committee of the Politburo and vice chairman of the SAC.41 These moves suggest that Pak will continue to have a major voice on economic affairs, while Choe will be able to steer the SPA to bolster Kim’s position and support Kim as first vice chairman of the SAC.

Also notable were the promotions of several others to the SAC: Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui; Kim Yong Chol, head of the united front of the KWP (in charge of South-North issues); Ri Su Yong, head of international affairs of the KWP; and Ri Yong Ho, foreign minister. Many of the old guard were replaced and key economic policy elites were promoted to the central committee.42 At the same time, Kim was referred to as the Supreme Commander of the DPRK, Supreme Leader of Our Party and State, and Supreme Leader of the Armed Forces. Previously, Kim was usually referred to as the Supreme Commander of the Korean People’s Army, rather than supreme leader of all of North Korea’s armed forces. This change signals even greater control over all military and paramilitary forces.43

Mindful of the ongoing pressure from international sanctions, Kim reaffirmed the importance of a self-reliant economy and the need for North Korea to continue to pursue a “my way” economic policy. He made a special point on “decisively enhancing the role of the Party organizations in the struggle to vigorously speed up the socialist construction under the banner of self-reliance.”44 Kim today is in full control of the party, the KPA, and the intelligence services and has begun to move loyalists into key positions. The real litmus test, however, lies in whether Kim is going to turn around the economy under onerous international sanctions while continuing to devote resources to WMD development.

The Power Beside the Throne

The one person who remains outside of any power flow chart is Kim Yo Jong. Her formal title is alternate member of the Politburo and deputy director of the Agitation and Propaganda Department of the KWP. Because she is of the Paektu bloodline, Yo Jong carries much more weight than even Kim Jong Un’s wife, Ri Sol Ju. By planting Yo Jong in one of the most important party departments, Jong Un is making sure that anyone else who wields significant power, such as Choe Ryong Hae, who heads the SPA and is also vice chairman of the party, can be checked.

As Kim Jong Il’s daughter, Yo Jong played a critical behind-the-scenes role in ensuring Jong Un’s succession. And, as described elsewhere in this book, she was the star of the opening ceremony of the February 2018 Winter Olympic Games in South Korea, and she never left her brother’s side during the April and May 2018 inter-Korean summits. The South Korean and world media made her into an instant global sensation. Her political influence is second only to her brother’s, although Kim might pull her back from the limelight if she gets too much attention. While Kim Yo Jong was next to her brother during meetings with South Korean president Moon Jae-in in 2018, and was in Singapore and Hanoi when Kim met with Trump, she was noticeably absent when Kim met with Russian president Vladimir Putin in Vladivostok in April 2019. Although the South Korean press speculated that this was a sign that Yo Jong’s influence was ebbing, it was more likely a deliberate move either by Yo Jong herself or by Kim Jong Un to control her much-reported public appearances.

Should anything happen to Kim Jong Un, Yo Jong would be able to succeed him, even though that runs contrary to conventional wisdom because she’s a woman, is relatively inexperienced, and has no military credentials. The only scenario in which she wouldn’t be able to succeed her brother is if the military launches a coup to take out the Supreme Leader and his entire family. Because of her position, she has learned many lessons about how to manipulate and cement power. She observed the silent but potentially deadly shifts in political loyalties after her father’s stroke in 2008. She also watched as her brother implemented bloody purges after he took power.

As previously discussed, during Kim Jong Il’s recuperation, day-to-day affairs were handled by Yo Jong’s uncle Jang Song Thaek—Kim Jong Il’s brother-in-law. Jang’s power stemmed from his marriage to Kim Kyong Hui—Kim Jong Il’s sister and Kim Il Sung’s only daughter. A pro-reform figure who was a key conduit to China, Jang was sent for several reeducation stints to remind him of his place in the power hierarchy. Yet Kim Jong Il always brought him back, since he needed a member of the royal family to carry out his orders.

But Jang’s status as a member of the family enabled him to build his own coterie of supporters and his own flow of hard-currency earnings. At the same time, he made enemies, not least because Kim Jong Il used him to keep his underlings at bay. Jang mistakenly believed that being married to royalty actually made him royalty.

“His fate was sealed a long time ago,” writes Ra Jong Il, a leading North Korea watcher, former deputy director for foreign intelligence at the NIS, and former national security advisor. “The beginning of the end for [Jang] was simultaneously Kim Jong Il’s death and Kim Jong Un’s rise. Perhaps it goes back even further, when Kim Kyong Hui was madly chasing after him, or to the period when he married her and was picked by Kim Jong Il and began on the road to power.”45 Jang’s fate was also affected by the fact that he was handsome, smart, and suave—all features that attracted people to him. In a system where even a hint of empire building can bring about a fall, Jang played with fire.46

As Kim Jong Il pondered his third son’s ascendance, he must have wondered: What if Jang killed him in a coup? Was Jong Un ready to stand up to the powerful generals? How was he going to purge the old guard?

Although Kim Jong Il needed Jang’s help to ensure that Jong Un took power, he must also have told Jong Un not to trust his uncle. Whether he explicitly told Kim Jong Un to kill his uncle when the time was ripe will never be known, but when absolute power and the legacy of a dynasty were at stake, killing one’s uncle was just part of what a Great Leader had to do.

And so as powerful as Kim Yo Jong is, and as much as Jong Un needs her, she can never be totally certain of her and her husband’s fate. Kim Yo Jong only needs to look at the misfortunes of her aunt Kim Kyong Hui. Kim Il Sung doted on her, and so Kim Kyong Hui and her husband, Jang, were untouchable as long as he or Kim Jong Il was alive. While their marriage faltered over time and their only child committed suicide, Kim Kyong Hui probably could never have imagined that her husband would be arrested, hauled off like an animal, and killed the same day.

This is the world that Kim Yo Jong inherited and in which she has to survive and thrive. A world where family members can be killed. A world where you really can’t trust anyone. A world where you always have to be on your toes.