Muhammad 'Abdul Jabbār

THERE was no parity in the agricultural contracts as between landlord and peasant. The relative proportion of shares between the parties varies considerably. This aspect of land-tenure presents a complex system of contracts, and an examination of these contracts sheds light on the agrarian economy of the 'Irāqi society wherein there was a large number of landless peasants and farm labourers. The tillers cultivated the lands of their absentee landlords, who were represented by their agents1 (wukalā') in peasant localities.

The peasants received a portion of crops in return for their labour, the remainder of the crops was taken away either by the landlords' agents or revenue officials. The share of the peasant in the crop was determined by various forms of bilateral contracts2 between the landlord and the crop-sharing tenant-farmers. The peasants' bargaining power was limited by the economic forces of demand for and supply of labour in a particular agricultural district, and the agricultural resources available there. If the supply of labour in a particular district fell short of the demand for it, the landowners had to offer favourable terms to attract peasants from other agricultural districts with the concomitant result that their share in the crop tended to rise.

We have two concrete cases from 'Abbāsid history concerning the response of agricultural labour to the economic forces of demand and supply under favourable and unfavourable agrarian circumstances. Favourable agricultural facilities offered to the akarah3 by a landlord resulted in an increase of productivity from the Land and consequently a larger dividend for the landlord. This also proved to be an incentive to labour mobility to the area concerned. Thus in the 4th century H./10th century A.D., when the wazīr Ibn al-Furāt's agent in a ḍay'ah in the ṭassūj4 of al-Anbar5 offered a hundred dirhams to the akarah and muzāri'ūn as an inducement, this brought an increased return from the ḍay'ah. When the fortunate akarah visited other rural areas and told their story of receiving the bonus of 100 dirhams, some of the peasants from those areas migrated to the former area. This increased supply of labour on the landed estate of Ibn al-Furāt increased the total output of crops to a record figure of 10,000 dinars.6 So when the demand for akarah was greater than the supply, their share in the produce increased in the above case; but an enormous increase in the supply of farm labourers would, in the long run, minimise the per capita share of each labourer in the crops. Let us examine a different case of labour response to a set of unfavourable circumstances.

In a document dated 377 H./987 A.D. we find that the peasants of the ṭassūj of Nahr al-Malik and that of Quṭrabbul had to work under the worst of conditions which led to a desertion of a number of akarah from the areas.7 The document further shows the ruination of sub-canals, extortion from the farmers by revenue-officials ('ummāl and mutasarriffūn), lack of facilities for providing seed and implements to the cultivators, thus weakening the local akarah and the muzāri'ūn. This naturally led to a fall in agricultural productivity due to the shortage of farm labourers. In order to bring back the deserted farms to cultivation, it became necessary to invite new akarah to the farm lands. The introduction of new akarah8 to the farming area tends to confirm that there was a large-scale desertion by farmers.

These two cases demonstrate that there were migratory farm labourers in some areas of 'Irāq, the migration being caused by agricultural circumstances. In other words, there was considerable mobility of agricultural labourers in agricultural districts, and they might not be "serfs tied to the soil9" as Yakubovsky supposed. These two cases were perhaps typical of the circumstances prevailing in the rural areas of 'Irāq in the 'Abbāsid period.

The word akarah mentioned above deserves a explanation. Etymologically, the word akkār (pl. akarah) means a cultivator 10 In the historical and literary sources, the akarah appear as landless peasants and farm labourers who cultivated lands of ḍiyā' holders on an unfavourable contractual basis.11 The word akkūr, of Aramāic origin,12 was used as an expression of contempt for the peasant.13

Among various forms of crop-sharing contracts al-mūzāra'ah is the most frequently mentioned in early juristic sources. The terms al-muzāra'ah, al-mukhābarah and al-muwākarah seem to be synonymous, referring to the institution of share-cropping.14 Lane explains the word al-muzāra'ah as "the making (of) a contract or bargain with another, for labour upon land (to till, and sow and cultivate it) for a share or portion of its produce, the seed being from the owner of the land."15 The share-croppers were usually known as al-muzāri'ūn.

Abū Yūsuf, a jurist of the 2nd century H. 8th century A.D., cites five different forms of agricultural contract current during the reign of Hārūn al-Rashīd (786–809 A.D.). In his discussion of crop-sharing agreements Abū Yūsuf mentions only one share (one-third, one-fourth, etc.) without specifying which party receives this share; he also mentions the burden of taxes to be borne by one or the other of the parties (peasant or landlord) depending on the terms of the contract.

The forms of contract mentioned in our sources do not usually specify the respective shares of the landlord and the peasant. However, the apparent uncertainty of respective shares does not in itself imply that one of the parties constantly received the larger share while the other party received only the lesser share. We have two independent pieces of evidence to suggest that there was no uniformity in the shares of the parties but that it was largely determined by practical considerations. For instance, in a document relating to Najrān16 (which was in the vicinity of al-Yaman) dated in the first half of the 7th century A.D. during the Caliphate of 'Umar b. al-Khaṭṭāb, it was stipulated that in the case of the land irrigated by rainfall, the Muslims, (i.e., the bayt al-māl17) would receive two-thirds of the crop and the remaining one-third would be received by cultivators; but if the land was artificially irrigated, the peasant would receive two-thirds of the net product while the Muslims would receive one-third.18 In the former case the peasants received one-third of the crops for the labour of cultivation, but in the latter case, they received two-thirds of it because they offered not only the labour of cultivation but also that of irrigating the land. Another piece of evidence shows that the peasant received one-third and the landowner received two-thirds of the product.19 The second piece of evidence, which was dated in the 2nd century H/8th century A.D., seems to confirm the first document which was of an earlier date. Thus the determining factor in the shares of the respective parties was the terms of the bilateral contract which was largely influenced by the agricultural conditions of the farm land.

The first form of al-muzāra'ah, according to Abū Yūsuf, demands that the landlord (not being able to cultivate the land by himself), offers his land with little or no condition, on a short term basis, to a cultivator who tills it, sows it with his seed and uses his own implements, and bears his own expenses.20 The cultivator under such an informal contract receives the entire product. If it is a kharāj-paying land, the kharāj is to be paid by the landlord (rabb al-arḍ); if it is tithe ('ushr) land, the 'ushr is to be paid by the cultivator, according to Abū Ḥanīfah.21 We have another version of this type of contract from an Ibāḍī jurist. Qatādah b. Di'āmah22 (d. 118 H./ 736 A.D.), like Abū Yūsuf, states the nature of the contract and gives his legal opinion on it. When a person offers his fallow land voluntarily to a cultivator on the stipulation that the latter would return it to the former some time after its reclamation, such a contract is makrūh,23 which means an "act whose omission is preferable to its commission."24 According to the Ibāḍī jurist, the farmer is not obliged to return the land to its owner, but if the cultivator returns it to the latter willingly, this is permissible.

The second form of muzāra'ah recorded by Abū Yūsuf differs considerably from the first in so far as the terms of the contract are concerned. This is, to a certain extent, a form of partnership in agriculture. The landowners invite peasants to cultivate their lands on the basis of crop-sharing.25 The parties involved in this contract share the expenses and also provide seeds equally and divide the product between them. If the land belongs to the category of kharāj, the landlord pays it, but if it is an 'ushrī land, the cultivator pays 'ushr.26 Qatādah's mention of this type of contract based on equal shares for the parties27 confirms, as one would have expected, that this form of share-cropping existed prior to 'Abbāsid times. Qatādah, however, adds something more than what Abū Yūsuf says about it. According to him, the contract is regarded as valid when the cost of cultivation is shared equally between the parties, but if the landowner demands from the cultivator an extra amount of rent for the use of water and land besides his share in the product, such a contract becomes makrūh (reprehensible).28 The mention of additional fees demanded by landowners from their tenants perhaps hints at the extortions associated with this type of contract. The juristic disapproval of these extortions only implies the seriousness of this problem.

The third in the series of muzāra'ah contracts recorded by Abū Yūsuf is the lease of fallow lands for a certain period in exchange for cash payment.29 Abū Yūsuf considers this a valid form of contract. The question of the payment of taxes under this form of lease contract is controversial. Abū Hanifah recommended that the taxes, be they kharāj or 'ushr, should be borne by the landlord, Abū Yūsuf contradicted the view of Abū Ḥanīfah and upheld the view that the burden of 'ushr, in the case of tithe-paying holdings, was to be laid on the lessee.30 Though legal opinion favoured payment of kharāj by the lessor, it appears that the lessee, in certain cases, paid kharāj along with his cash rent to the landlord.31

The fourth form of al-mnzāra'ah is the form of share-cropping contracted on the basis of one-third or one-fourth share in the crop. That muzāra'ah of this forms a recurrent theme in juristic literature indicates its widespread practice in the Arab Orient. According to Zaid b. 'Alī, muzāra'ah of this form for a period of a year or more is legal.32 Under this contract, the entire work is done by the tenant cultivator, and the obligation to supply seed is on either party,33 as agreed upon between them. In either case, the contract remains legally valid, but if the landlord imposes additional labour on his tenant, other than that of cultivation, the contract becomes irregular and void (fāsid wa bāṭil).34 Abū Hanīfah dismissed this type of muzāra'ah as fāsid (irregular) and recommended a wage commensurate with the work of the tenant.35 The kharāj on this land is to be paid by the landlord alone.36 Al-Rabī' b. Habīb (d. 160 H. 776 A.D.),37 an Ibadi jurist of Basrah, reacted less vigorously against this type of muzarā'ah and he regarded this only as makrūh (reprehensible).38 Jābir b. Zaid, an earlier Ibāḍī jurist, also disapproved of muzāra'ah on the agreement of one-third and one-fourth shares in the product.39 Jābir b. Zaid, like Abū Hanīfah, recommended an alternative measure to this legal problem—that the landlord, instead of engaging a crop-sharing tenant on one-third and one-fourth shares in the crop, should employ hired labour at a fixed wage.40 Under the terms of this contract the landlord provided his tenant with all the necessary means of production such as the land, seed, oxen, etc. The tenant cultivator offered only his labour. In spite of this, some jurists objected to this form of contract because, if the crop failed as a result of unforeseen natural calamities, the labour of the tenant41 went completely unrewarded. Therefore, the recommendation of using hired labour, or paying a wage commensurate with the labour of the tenant under such a contract, appears in a consensus of opinion among a large number of jurists of different schools.

It is quite interesting to note that Abū Yūsuf offered his approval of contracts on one-third and one-fourth shares in the crop.42 In defending this type of muzāra'ah against those who condemned it, Abū Yūsuf, unlike any other jurist, was probably justifying the legality or status quo of the agricultural practices of this time.

According to the fifth type of al-muzāra ah, the landlord provides his land, seeds, oxen and other expenses for an akkār, who cultivates the field on the basis of one-sixth or one-seventh share in the crops.43 While Abū Hanīfah denounces such a contract outright as fāsid (legally void), Abū Yūsuf defends its legality.44

The akkār, mentioned in the above contract, formed an important group of farm labourers. It is interesting to note that the akarah (sing, akkār), who appear in our sources as farm labourers as well as crop-sharing tenant farmers seem to have come from the peasants of the Nabaṭī stock. This statement is corroborated by two separate documents, one of which described a person as Nabaṭī,45 while the other described the same person as an akkār46—thus the words Nabati and akkār appear synonymous, Both the sources further described the Nabaṭī and the akkār as a person from the Sawād which was by far the most fertile agricultural area in the Tigris-Euphrates valley. It may be added here that the word akkār, according to Fraenkel, is a word of probable Aramaic47 origin. As stated earlier, the Nabaṭī peasants spoke the Aramaic language, which accords additional support to the statement of the Aramaic origin or akkār. However, the akarah, it appears, formed the poorest group of farm labourers and they were liable to pay only the least amount of jizyah48 (poll-tax) on account of their comparative poverty among the peasants of 'Irāq at the beginning of the Arab conquest.

The akarah were said to have cultivated lands on a contract which presumably offered them a snare of one-sixth or one-seventh in the crops. This particular economic condition of the akarah bears a striking resemblance to that of the "hectomoros"49 or six-parters (those who received one-sixth of the crop) of Attica in ancient Greece. They were the only group of farmers tied to the soil receiving a minimum share in crops, according to Giotz.50 However, the similarity between the akarah and the hectomoros cannot be carried too far. The akarah, in contrast to the hectomoros, were not the only group of farmers in Sawād. The other prominent groups of the peasants and farm labourers who existed side by side with them were the muzāri'ūn and the 'irrīsūn.

In the early political documents of Islam of the first century H./7th century A.D., collected and edited by Muḥammad Ḥamidullāh,51 and also in the K. al-Amwāl of Ibn Sallām,52 we find references to the 'irrīs (pl. 'irrīsūn). According to Khalil al-Harās, the 'irrīsūn denotes the subject people in general.53 On the other hand, Hamīdullaḥ54 and Fraenkel55 relate the word 'irrīsūm to farm labourers and crop-sharing peasants. The latter states that the word "'irrīs" according to an explanation in 'Āruch, denotes a man who receives a patch of land from the landowner and cultivates it; subsequently the crop, after harvesting, is shared between the landowner and 'irrīs.56

The akarah also appear among labourers in horticultural land57 growing date-palms. Al-Ṣābī describes the akarah as eating "bread with onions and milk";58 Jāḥīz mentions certain mashāikh al-akarah59—a statement implying some form of organised life of the akarah headed by mnshāikh.

Jāḥiz cites an interesting case of the akkār of a miser (bakhīl),60 probably of his own time, in his literary masterpiece K al-Bukhalā'.61 The story runs as follows:

There was a miser in Baṣrah named Ibn al-'Aqadi who was a rice merchant. He had an akkār. The miser employed his akkār to husk rice, then scatter and sieve it, and husk it again. When rice was husked, the miser made his akkār grind it with the help of oxen in the mill. When the grinding was over, the miser then āsked his akkār to fetch water (from a well), then to bring firewood. When all these items were assembled, the akkār had to boil water and knead the flour with hot water, and finally to prepare bread out of it.

The miser's friend would catch fish with hooks; in the meantime, the akkār prepared kabāb out of the fish without adding any extra fuel to the burning oven. The dinner was served at last to the guests of the miser at night with black bread (made of rice flour unsifted in sieve) and kabāb of roasted fish.62

The above anecdote throws additional light on the akarah who were primarily farm labourers; but an akkSr appears in the story as a domestic servant. The working conditions of the domestic akkār are also portrayed vividly in the story. Leaving aside the literary exaggeration of the story to heighten its effect, Jāḥīz has evidently recorded, in the characters of al-'Aqadī and his akkādr, the tale of a hard task master and the toiling labourers of his time.

Besides the five different forms of muzāra'ah recorded by Abū Yūsuf and often elaborated by other jurists, there seem to have existed, in the customary law of 'Irāq, some other forms of share-cropping contracts. Jābir b. Zaid, an Ibāḍī jurist of 'Irāq (d. 711 A.D.)63 recorded two such customary contracts. For instance, a landowner provides land, water facilities for irrigation, implements, oxen and seed for the share-cropper. The sharecropper accepts this arrangement and he works relying on the good faith of the landowner. The share-cropper performs his duty without fixing any specific share in dividing out the product of the land. When the harvest is reaped, the landlord gives a share of the product to the share-cropper. The work is done to the mutual satisfaction of the parties concerned. When asked for his legal opinion on such a contract, Jābir b. Zaid expressed his approval by saying, "There is no harm in it."64

In another contract cited by Jābir b. Zaid we find that a farm labourer works on the land of a landowner on the understanding that he will receive a share in the product. Both the contracting parties spend an equal amount of money, and, furthermore, the landowner offers his servant to assist the share-cropper.65 They share the crop between themselves. Another report in the same document shows that one of the contracting parties performs a greater amount of work than the other partner. If such work is done voluntarily, Jābir b. Zaid approves of it as legal.66

While Jābir b. Zaid, the Ibāḍī jurist of 'Irāq (d. 711 A.D.) approves of share-cropping contracts without specific terms, al-Rabi' b. Habīb, another Ibāḍi jurist (d. 8th century A.D.), challenges the legality of a contract that fails to specify the shares of both the parties in the crops. The informal contract cited by al-Rabī' b. Habīb runs as follows, "If a person says, 'Work on my land or in my orchard and I will satisfy you; and I shall do you some favour'."67 But the landowner does not specify any fixed share in the crops. In such a case, "the cultivator deserves a wage commensurate with his work."68

All these cases cited by Jābir b. Zaid and al-Rabī' b. Habīb corroborate our statement that, side by side with the five different types of muzāra'ah cited by Abū Yūsuf, there existed some customary contracts without defined shares assigned to the parties concerned.

The institution of muzāra'ah in all its different forms offers us an understanding of the relations between the landowners and the share-croppers in 'Iraq during the 'Abbāsid period. The share-croppers received a share for their labour on the land, while the landowner got his share in it on account of his ownership of the property. The respective shares in the crop as between the landowner and the share-cropper were determined by the terms of the contracts, or by customary law, which seems neither to have been designed exclusively to serve the vested interests of the landowning class, nor to operate uniformly to the advantage of the share-croppers and farm labourers.

Besides the muzāri'ūn, 'irrīsūn and akarah, there were other groups of agricultural labourers in 'Irāq known as ḥarrāthūn (literally, ploughmen), ḥawāṣid (harvesters), gharrāfiyūn and so on. The ḥarrāthūn were hired labourers who ploughed the lands of landowners for a cash wage.69 Jāḥiz mentions them among different groups of labourers and adds that they could never become rich.70 The hawāṣid (harvesters)71 were seasonal workers who worked during the harvesting seasons.

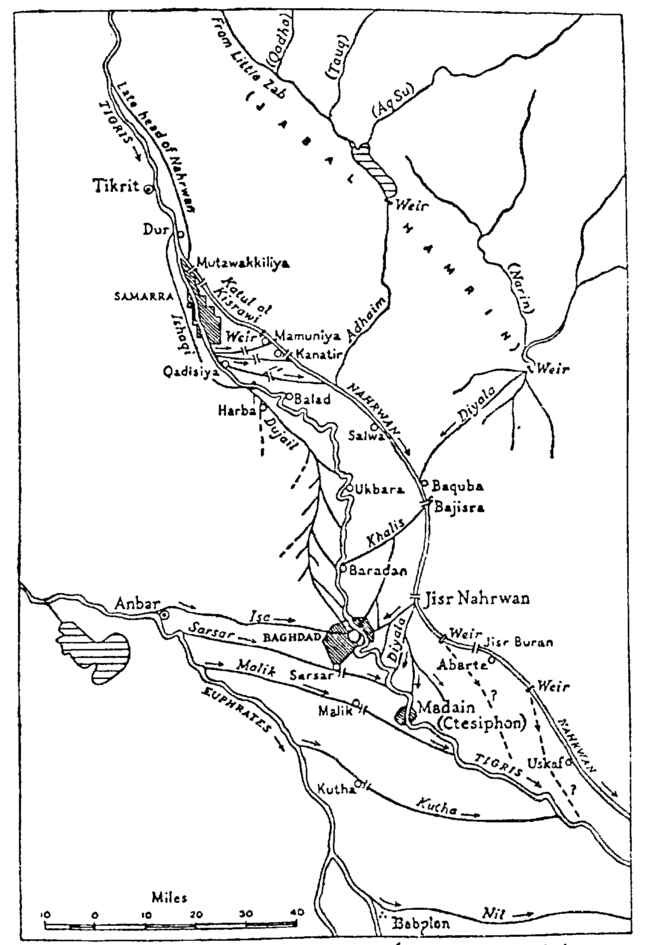

The supply of water has always been a limiting factor in the agricultural development of 'Irāq, as is the case in every country. The 'Abbasid Caliphs paid special attention to the restoration, expansion and maintenance of a vast irrigation network in 'Irāq. This vast irrigation network required a large number of labourers to operate such machines and wheels as dūlāb, dāhyah, gharrāf, nā'ūrah, zurnūq,72 shadhūf73 and the like. These were skilled or semi-skilled labourers and artisans.

The publication of relevant extracts from the K. al-Ḥāwī li 'amal al-Sulṭānīyah wa rusūm ḥiṣāb al-Diwānīyah (Paris, B.N. arabe No. 2462) by Cahen has focused new light on the irrigational works in "Irāq during the 'Abbāsid period. We will go into some details about the different irrigational apparatuses in the following paragraphs.

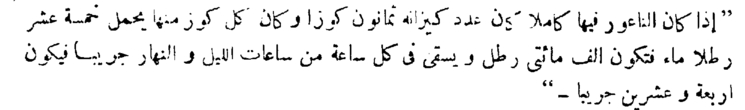

A nā'ūrak is a wheel which rotated on "an axis which was usually supported by two uprights and was set in motion by a pair of buffaloes or camels."74 A complete nā'ūr contains eighty tankards (kīzān), of which each tankard (kūz) carries fifteen pounds (lbs.) of water; therefore, the total capacity of a nā'ūr was twelve hundred pounds of water. A nā'ūr could irrigate one jarīb of land per hour, and twenty-four jarībs in a day and a night.75

The dūlāb was smaller than nā'ūr. It was operated either by one or two oxen depending on its size. The dūlāb operated by one ox could irrigate ten jarībs of land a day. It irrigates seventy jarībs of land in winter and thirty jarībs in summer. On the other hand, a dūlāb run by two oxen irrigates one hundred and fifty jarībs in winter and seventy jarībs in summer.76 The nisbak al-dūlābī77 was suffixed to the proper names of those who were either workers at the dūlāb, or owners of it.

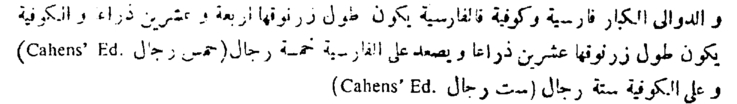

The large dawālī (al-dawālī al-kibār) were of two types viz., the Persian dawālī of the size of twenty-four dhirā' (cubits) and the Kufan dawālī whose zurnūq was twenty dhinā' in size.78 The Persian dawāli was operated by five workers and the Kufan dawāli was operated by six labourers.79

Gharrāf was another irrigational apparatus. The workers at the gharrāfs were known as gharrāfiyūn80 (singular, gkarrāfī). Jāḥiz mentions the term shaykh al-gharrāf,81 which, we presume, refers to the chief of the workers at a gharrāf.

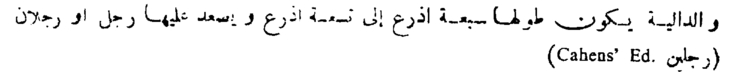

The dāhyah which we have already mentioned, was operated by one or two workers 82

Shādhūf, another irrigation apparatus, was operated by four workers.83 It could irrigate seventy jaribs of land in winter and thirty jaribs in summer.84

The irrigation works needed the services of many technical hands, besides those of the ordinary labourers. Some of these workers were the qayyāsūn or ḥmssāb85 who supervised the distribution of water between canals and subcanals, the muhandisūn86 who were associated with the digging of canals, and the 'arīf87 who was some kind of a contractor in charge of supplying labourers for irrigation works.

It is also reported that the muhandisūn received, perhaps as their fees, an amount of money expressed in mathematical terms as a quarter of al-'ushr (rub' al-'ushr).88 It is, however, not very clear what the phrase rub' al-'ushr mimma yudkhalu fī al-nafaqah precisely means.

On the other hand, the 'arīf, who was responsible for supplying labour for irrigation works, received a fee for his service, technically known as ḥaqq al-'irāfah.89 This fee was a customary impost (rasm) for the 'arīf who received two ḥabbahs (ḥabbatān) for the supply of each labourer. In any case, it is in itself an important fact that there was an institution of 'arīf among the irrigation labourers and that he received a customary fee for his work. The institution of 'arīj was also known among the other groups of labourers and artisans such as weavers, sweepers, mint workers ('arīf al-naqqādīn),90 as also among the members of the futuwwah. The customary fee ḥaqq al-'irāfah, it may be deduced from the above instance of the 'arīf of irrigation workers, was not likely to be uncommon among all 'urafā'.

It seems necessary to elaborate on the role of the muhandisūn in irrigation works of the medieval Middle East. In Arabic sources of the 'Abbasid period there are references to muhandisūn along with the construction workers engaged in building capita! cities such as Baghdad and Sāmarrā'. This seems to have created misunderstanding about their role. Graber's view that the muhandisūn were "in charge of laying out of Baghdad"91 needs to be modified in the light of evidence collated by us. We have reasons to believe that the role of the engineers in the actual building works of the 'Abbāsid capitals was indirect and negligible. The muhandisūn, it seems, were in charge of digging canals which intersected major 'Abbāsid cities.

Al-Khwārizmī defines that "a muhandis is he who measures the streams of canals when these are to be dag."92 There are more evidences which corroborate al-Khwārizmi's statement. Al-Ya'qūbi, while describing the foundation of the city of Sāmarrā', used the phrase "handasat al-mā'"93 (water engineering) which indicates the work of the muhandisūn. Abū Hayyān al-Tawhīdī94 adds more evidence which lends supports to al-Khwārizmī's statement.

In spite of their useful role in economic development of Arab land, the public were critical of the profession of the engineers. To earn a livelihood through the professional skill was perhaps considered demeaning, while the possession of the knowledge of engineering for its own sake was applauded. In the words of al-Tawḥīdī, "The engineers, when they use their knowledge as a craft, become like the canal-diggers (i.e., menial workmen), or like those who dig streams in a valley, or like a man who constructs a public bath."95 All these evidences tend to suggest that the role of the muhandisūn was limited to the work of "water engineering" and they were expert planners associated with the projects of digging subterranean canals. The digging and repair of canals in 'Abbāsid 'Irāq was the joint responsibility of the Diwān al-Mā' and Diwān al-Kharāj. The Government, we gather, employed experts such as muhandisūn, qayyāsūn and 'arīj who, in turn, assembled the labourers to canal projects. Among some skilled artisans working at canals were the naqqātūn who dispersed the useless rubble and the razzāmūn or reed-binders who skilfully used reeds for dam construction. The Kitāb al-Hāwī, cited above, is the source of this rare irrigational information.

A large number of quasi skilled workmen were employed for the grand projects of digging canal network for agricultural development of Mesopotamia under the Ummayyads and 'Abbāsids.

It is reported that during the Ummayyad period Hajjāj b. Yūsuf96 used forced labour for digging some canals. In describing the canal diggers of the Ummayyad period, al-Balādhurī used such terms as al-fa'alah,97 described by Lokkegaard as socage-labourers,98 while Fahd describes them as terrasiers.99 Sometimes the canal-diggers are merely described by such an imprecise expression as rajul min al-ḥaffārīn.100 Absence of a definite technical term to describe canal-diggeis during the Ummayyad period may be taken as an indication that there was no regular group of labourers in 'Irāq at the period. The employment of forced labour in digging canals during the Ummayyad period further affirms this argument. Since the projects of digging or re-digging of canals were undertaken after a considerabie lapse of time by the Caliphs or princes or even by private enterprise, the existence of a regular group of canal-diggers in Ummayyad 'Iraq was not likely.

The position of canal-diggers in 'Abbāsid 'Irāq appears to be quite different from that of the previous epoch. We have not only a. vivid account of the network of canal systems but also a plurality of technical terms to describe canal-diggers—a development suggestive of the increase in the number of these workers in 'Irāqī society. Al-Mubarrad (d. 895 A.D.) mentions the word 'qanna' (alā)101 to denote canal-diggers. The writing of Ibn Serapion, a topographer of Baghdād and Mesopotamia, (c. 900 A.D.), described the canal-diggers as aṣḥāb al-qanā,102 who lived in a special quarter of Baghdād.103 Ibn Serapion's description of the canal-diggers' quarter in Baghdad in the late gth and early 10th century A.D. indicates that these workers had a recognised position in society The Ikhwān writers also mention the craft of the canal-diggers,104 and Abū Ḥayyān al-Tuwḥīdī described them as ḥāfir ul-anhār.105 From this evidence we may conclude that there was a constant supply of the labour of canal-diggers in "Abbāsid 'Irāq, and the landowning class was always ready to make use of this important labour force.

Musāqāt is a technical term associated with horticultural products,106 namely, dates, grapes, olives107 and the like in 'Irāq, as well as in other neighbouring Arab countries, both preceding and during 'Abbāsid period. Von Kremer108 describes musāgāt as a "gardening contract" which consisted of "one person taking charge of orchards, vineyards and vegetable gardens for a share in the produce."

According to Ibn Hawqal. horticultural products were grown in different areas of 'Irāq and the Jazīrah province, in Mauṣil,109 Sinjār,110 Ra's al-'Ayn,111 Jazīrah b. 'Umar,112 Baṣrah,113 Kūfah,114 Wasīṭ.115 Baghdād,116 Sāmarrā'117 and their peripheries. According to the mnsāqūt contract, horticultural products were shared between the landou ner and the cultivator since the days of Prophet Muḥammad.118 The shares of the cultivators were in some cases half the product, in other cases one-third of it, or a quarter.119 Among the jurists, Abū Yūsuf admitted as valid all forms of agricultural contracts between the landowner and the tenant-cultivator.120 But Abū Hanifah disapproved of contracts which failed to ensure a fair share for the farmers, and he regarded them as reprehensible (makrūh)121 Von Kremer, an admirer of the Hanafī school of Law, comments, ".......Abū Hanīfah, with great consistency, has condemned all agreements in which the gain or profit was uncertain and where one party might get too much or too little."122 Al-Rabī' b. Habīb, an Ibāḍī jurist who subscribed broadly to the legal opinion of Abū Hanīfah regarding masāqāt, recommended that date-palms should be cultivated only by employing hired labourers.123

Under normal agricultural conditions, it appears, the farm labourers in horticultural products did not necessarily suffer uniformly from unjust shares on account of the plurality of gardening contracts which entitled them to different shares varying from a quarter to a half of the net product.124

A group of labourers employed for guarding horticultural plantations in 'Irāq, particularly in the Sawad area, were known as nawāṭīr (sing. nāṭūr).125 We come across a number of references to them dotted over the vast field of Arabic literature of the 'Abbāsid and post-'Abbāsid periods. Jāḥiz is one of the first Arab writers to pay some attention to them. In her thesis on the literature of Jāḥiz, Dr. Waḍī'ah126 mentions the relevance of nāṭūr to agriculture, although she does not explain the relevant texts of Jāḥiz in detail.

Linguistically speaking, the word nāṭūr is believed to have been derived from the Arabic word al-nāzūr (روظال), according to Aṣmā'ī, who explains the transformation of the word from one form to another.127 It is stated that the transformation of the word took place due to the inability of the Nabaṭi to pronounce ظ which they pronounced as ط.128 A Nabaṭī or Aramaic origin of the word is also suggested by some linguists.129 This may be established, apart from linguistically, purely on circumstantial evidence. Since the word nāṭūr was used by the Nabaṭī peasants of al-Sawād,130 as some writers admit, the possibility of an Aramaic origin for the word is very strong. However, in spite of the linguistic wrangles about the origin of the word, the connotation of it as watchmen of gardens is agreed upon without dissent by all writers of the 'Abbāsid period.

Jāḥiz portrays the nāṭūr in action. The Banū Asad131 of al-Yamāmahl32 sent one of their negro slaves as a nāṭūr to a farm, probably in Sawād, where he did not meet anybody but the akarah,133 who were the indigenous farm labourers of 'Irāq. The negro nāṭūr was said to have failed to understand the language of the akarah, who were Aramaic-speaking farmers, and, therefore, he spitefully cursed the locality, by saying, "May God curse the land where there is no Arab?."134

There are two other stories which explain the working conditions and manners of the nawāṭīr. Al-Qazwīnī tells the following story of a certain Ibrahim, who was a wage-earner, a nāṭūr.135The event that follows was reported to have taken place in 161 H./777 A.D.; the nāṭūr was asleep when a soldier (jundī) came and asked for some fruit. Thereupon, the nāṭūr replied, "I am only a watchman, and the ow ner of the garden did not permit me to give away anything ( from the garden to any stranger)."136 At this, the soldier became angry and beat the nāṭūr to death. The above story portrays a nāṭūr of the early 'Abbāsid peiiod and how he remained steadfast in his duty. The loyalty of the watchman to his master was the cause of his death. The soldier, on the other hand represents an irresponsible intruder (into the garden) who attempted to cnforce his unjustified demand through violence. This story, above all, typifies the difficult working conditions of some watchmen.

In sharp contrast with the above portrayal of a nāṭūr, Jāḥiz tells us of another watchman who was hospitable to the visitors to a garden. We are told that some Arabs were passing by nāṭūr on the bank of al-'Ubullah canal. These visitors were weary and they sat beside the watchman, who offered them some food 137 In contradistinction with the miserly characters of the K. al-Bukhlā,138who were notoriously reluctant to offer food to others, the nāṭūr of al-'Ubullah appears as a hospitable character. Jāḥiz, by narrating the story, expresses his appreciation of the extravagantly generous manner of a humble worker, who stood in sharp contrast with the niggardly social manners of the affluent misers (bukhalā).

The word "nāṭūr," according to Ibn Ṭūlūn, underwent semantic change during the Mamluk period and it was used to denote a guard at the public baths (ḥammāmāt ).139 However, according to contemporary evidence, the nawāṭir in Syria140 and Lebanon141 are no other than the watchmen of horticultural plantations and they are often subjected to the jibes of the common folk in a number of current Arabic proverbs.

The author wishes to thank Professor R.B. Serjeant for supervising the writing of the essay at Cambridge, and also Professor M.A. Mu'id Khan for useful assistance.

(1) Al-Ṣābī, al-Wuzarā', editor Amedroz, Leyden, 1904, 216;

(2) Cf. 'Abd al-Razzāq al-Sanhūrī, Maṣādir al-haqq fī al-fiqh al-Islāmī, I, sighat al-'aqd, Cairo 1954, the Islamic Law on contracts, G.L.R., 1953, (A symposium on Muslim Law), 32–39; Cbafik Chehata 'Akd, E.I. second edition, I, 318 ff.

(3) Al-Ṣābī, loc. cit., 259.

The essay is based on a chapter of doctoral thesis: "The social history of the labouring 'classes' in 'Iraq under the 'Abbāsids", approved by the University of Cambridge in July, 1971.

(4) Cf. V. Minorsky, article Ṭasudj (and Ṭassudj), E.I. (1), IV, 692; Tassuj is a territorial division meaning a district in al-'Iraq. "The division into tasudj must have been based on irrigation."

(5) Yāqūt, Mu'jam, I, 367–368.

(6) Al-Ṣābi, loc. cit., 259.

(7) Al-Qalqashandī, Subḥ al-a'shā, Cairo, 1918, (XIX vols.), XIII, 139.

(8) Ibid., (XIV vols.), XIII, 140,

(9) A. Yakubovsky, Ob ispolnikh v Irake VIII v., Sovetskoe Vosotkovedenie, Moscow, 1947, IV, 179.

(10) Ibn Manzūr, Lisān al-'Arab, Beirut, 1955, IV, 26; Cf. also M. Hamid Allah Majmu'at al-Wathā'iq al- Siyāsīyah, Cairo, 1941, 257; according to Hamid Allah, akara denotes ploughmen (ḥarrāthūn) and peasants (fall ā hūn), cf. Ibid.; Sharh al-alfāz (Glossary), 298; Al-Shabushtī, K. al Diyārāt, editor G. 'Awad, Baghdād, 1966, 215, f. n.; Hilāl al-Sābī, Rusūm dār al-khilāfah, editor, M. 'Awad, Baghdād, 1964, 8 f. n.; Lane, Lexicon, I, 71.

(11) Ahmad Pashā Taimūr in Majalla al-Majma' al-'Ilmī al-' Arabī, Damascus, 1922, II, No. 10, 291; according to Taimur, the word muwākarah (derived from akarah) in customary law ('urf) denotes a certain share in agricultural product, specially one-third and one quarter. The common folk in Egypt use the word akarah in the sense of al-murāba'ah which was originally al-muzāra'ah 'alā al-rub', i.e., cultivation of land on a contract specifying one-fourth share in the product, cf. also A. Marie al-Kirmīlī, Alfāz Nishwār al-Muḥādarah, Majalla al-Majma' al-'Ilnū al-'Arabi, Damascus, 1923, III—IV, 91; Løkkegaard, Islamic taxation in the Classic period, Copenhagen, 1950, 176; Tanūkhī, Nishwār al-Muhādarah, London, 1921, 1, 4; Ibn Ḥawqal, K. Sural aS-Arḍ, editor J.H. Kramers, Leyden, 1938, 1, 217; Al-Balādhurī, Futūh al-Buldān, editor de Goeje, Leyden, 1866, 158.

(12) Fraenkel, Die Aramāischen, 128–129.

(13) Ibn Manzūr, op. cit., IV, 26: al-Ṣābī, The historical remains, 92.

(14) Ibn Qudāmah, al-Mughnī, Cairo, 1947, V, 383; cf. also Ahmad Pasha Taimūr, in Majallah al-majma' al- 'Ilmī al-'Arabī, II, No. 10, 291; Ibn Manzūr Lisān al-'Arab, IV, 26; Lane, loc. cit., I, 71; III, 1226.

(15) Lane, Lexicon, III, 1226.

(16) According to Arab geographers, there was a Najrān in Northern Yaman, another in southern Najd or in Ḥijāz; cf. A. Moberg, article Nadjrau, E.I., first edition, III, 823 ff.

(17) Bayt al-mal was the public treasury of the Caliphal state.

(18) M. Ḥamīdullah, al-Wathā'iq al-Siyāsīyah, Cairo, 1941, 100.

(19) Al-Rabī' b. Ḥabīb, Riwāyāt Ḍumām, fol. 55; I am indebted to A.K. en-Nami for this document. Cf. A.K. Ennami, A description of new Ibāḍī MSS., J.S.S., XV, I, 1970, 68,

(20) Abū Yūsuf, K. al-Kharāj, Būlāq, 1302/1884, 51.

(21) Ibid., 51.

(22) Sezgin, G.A.S., Leyden, 1967, 248.

(23) Qatādah, Aqwāl Qatādah, III, fol. 131.

(24) Aghnides, Muhammadan theories of finance, 1916, 114.

(25) Abū Yūsuf, loc. cit., 51.

(26) Ibid., 51.

(27) Qatādah, Aqwāl, part III, fol. 131.

(28) Ibid., fol. 131.

(29) Abū Yūsuf, loc. cit., 51.

(30) Ibid., 52.

(31) Al-Shaibānī, al-Makhārij, editor J. Schacht, Leipzig, 1930, 19.

(32) Zaid b. 'Alī, Musnad Imam Zayd, Beirut, 1966, 284.

(33) Zaid b. ' Alī, Musnad Imam Zayd, Beirut, 1966, 284.

(34) Zaid b. 'Alī, loc. cit., 284; s.v. fāsid wa bāṭil, (2), II, 829–830.

(35) Abū Yūsuf, loc. cit., 52.

(36) Ibid.

(37) Fuad Sezgin, G.A.S., Leyden, 1967, 248.

(38) Al-Rabī' b. Habīb, Riwāyāt Ḍumām, fol. 55.

(39) Jābir b. Zaid, Rasā'il, editor A.K. Ennami, Risālah No. 8.

(40) Ibid.

(41) Qatādah b. Di'āmah, Aqwāl Qatādah, III, fol, 131.

(42) Abū Yūsuf, loc. cit., 52.

(43) Ibid.

(44) Ibid.

(45) Al-Nawbakhti, K. Firaq al-Shi'ah, Bibliotheca Islamica 4, Istanbul, 1931, 61.

(46) Al-Baghdādī, Mukhtaṣar K. al-Farq bayn al-Firāq, editor P.K. Hitti, Cairo, 1916, 171.

(47) Fraenkel, Die Aramaischen, 128–129.

(48) Al-Balādhurī, K. Futūḥ al-Buldān, editor de Goeje, Leyden, 1886, 271.

(49) Giotz. Ancient Greece at work, London, 1926, 81.

(50) Ibid.

(51) M. Hamīdullah, al-Wathā'iq al-Siyāsīyah, Cairo, 1941, 257.

(52) Ibn Sallām, K. al-Amwāl, Cairo, 1969, 33.

(53) Ibid., 33 f.n.

(54) Ḥamīdullah, op. cit., 297.

(55) S. Fraenkel, Die Aramaischert Fremdworter im Arabischen, 1886, 128.

(56) Fraenkel, Die Aramaischen, 1886, 128–129.

(57) Al-Shabushlī, K. al-Diyārāt, Baghdad, 1966, 215.

(58) Al-Ṣābi, Some lost fragments of K. al-Wuzarā', editor M. 'Awad. Baghdād, 1948, 49.

(59) Jāḥīz, K. al-Ḥayawān, editor Hārūn, Cairo, 1938–40, V. 32.

(60) Cf. Ch. Pellat, article Bukhl, E.I., sccond edition, I, 1297; in Arab society generosity has always been applauded, while avarice furnishes a theme for satire. In the literary polemics of the 'Abbāsid times, the non-Arabs were satirized as misers (bukhalā'). The portrayal of misers in Jāḥiẓ's K. al-Bukhalā' had such political undertones

(61) Jāḥiẓ, K. al-Bukhalī editor Taha al-Ḥājirī, Cairo, 1963; 129. Cf. Ibnu'l Jawzi, Dhamm al-Hawā, Cairo, 1962, p. 273, also narrates a story of an Akkar of Baṣra.

(62) Jāḥiẓ, loc. cit., 129.

(63) Cf. A,K. Ennami, "A description of new Ibāḍī manuscripts from North Africa," Journal of Semitic Studies, XV, No. 1, 1970, 65.

(64) Jābir b. Zaid, Rasā'il, editor A.K. Ennami, risālah No. 14.

(65) Ibid., Risālah No. 8.

(66) Ibid., 8.

(67) Al-Rabī' b. Habīb, Riwāyāt Ḍumām, part 11, fol. 55.

68) Ibid., fol. 55.

(69) De Goeje et de Jong, Fragmenta Historicorum Arabicorum, Leyden, 1869, III, 408; Ibn Hawqal, K. Ṣūrat al-'Arḍ, editor Kraemers, Leyden, 1938, I, 213.

(70) Jāḥiẓ, al-Ḥayawān, IV, 434.

(71) Al-Maqdīsī, Aḥsan al-Taqāsim, B.G.A., III, 1877–79, 138.

(72) Al-Khwarizmī, Mafātiḥ, 71.

(73) Cahen, "Le service de l'irrigation en 'Iraq au debut du Xle siecle", (referred to hereafter as K. al-Ḥāwī), B.E.O., Daraas, 1951, XIII, 118–119.

(74) Belyaev, The Arab Caliphate, 207.

(75) K. al-Ḥāwī, 118.

(76) Ibid., 118.

(77) Al-Sam'ānī, al-'Ansāb, V, 411–412.

(78) K. al-Ḥāwī, 118.

(79) Ibid, 118.

80 Aslam b. Sahl, Tārīkh Wāsiṭ, Baghdād, 1967, 27.

(81) Jāḥiẓ, K. at-Bayān wa al-Tabyīn, Cairo, 1947, III, 209.

(82) K. al-Ḥāwī, 118.

(83) Ibid., 1 18–119; Shādhūf was also used in Egvpt; cf. Belyaev, loc. cit., 207.

(84) Ibid., 118–119.

(85) K. al-Ḥāwī, 121.

(86) Ibid., 127.

(87) Cahen, loc. cit., 127.

(88) K. al-Ḥāwī, 127.

(89) Ibid., 127.

(90) Cf. M.A.J. Beg, "The social history of the labouring classes in 'Iraq under the 'Abbasids (750–1055 A.D.)," MS. Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge, 1972, fol. 304–306.

(91) O. Grabar, Review of L. Mayer's Islamic architects and their works A.O., 1959, 221–222.

(92) Al-Khwārizmī, Mafātiḥ al-ulūm, Leyden, 1895, 202.

(93) Al-Ya'qūbī, Kitāb al-Buldān, Leyden, 1860, 391; cf. also Jāḥiẓ, al-Tabassūr bi-i-iijārah, 33–34.

(94) Al-Tawḥīdī, al-Muqābasāt, Cairo, 1929, 328.

(95) Al-Tawḥīdī, Risālutān, Constantinople, 1301/1883, 206.

(96) Al-Balādhuri, Futuḥ al-Buldān, Cairo, 1956–7, 336, 355.

(97) Ibid., 355.

(98) Løkkegaard, Islamic Taxation, Copenhagen, 1950, 178, 261.

(99) T. Fahd, Les corps de metiers au IV/Xe siecle a Baghdad, d'apres le chapitre XII d'al-Qādirī f ī al-ta'bir de Dinawarī, J.E.S.H.O., 1965, VIII. 189–190.

(100) Al-Balādhurī, op. cit., 336.

(101) Al-Mubarrad, al-Kamnil, editor A.M. Shākir, Cairo, 1937, III, 961; Fahd, Les corps de metiers, J.E.S.H.O., 1965. VIII, 201.

(102) Le Strange, Ibn Serapion's description of Mesopotamia and Baghdad, J.R.A.S., 1895, 26.

(103) Le Strange, Baghdad during the 'Abbasid Caliphate, London, 1900, 78.

(104) Rasa'il Ikhwan al Ṣafa', Cairo, 1928, I, 214.

(105) Al-Tawḥīdī, Risalatan, Constantinople, 1301/1883, 206.

(106) S.M. Yūsuf, "Land, agriculture and rent in Islam," I.C., XXXI, 1957, I, 29.

(107) Saḥnūn b. Sa'īd, Mudawwanah (k. al-musaqat), (XVI volumes), Cairo, 1905, XII, 6.

(108) Von Kremer, The Orient under the Caliphs, translator S.K. Buksh, Calcutta, 1920, 420.

(109) Ibn Ḥawqal, K. Ṣūrat al-'Arḍ, editor Kraemers, Leyden, 1938, I; 215.

(110) Ibid., 220; Ibn Ḥawqal reports that fruit was grown in Sinjār both in winter and summer seasons.

(111) Ibid., 322.

(112) Ibid., 224–5.

(113) Ibn Ḥawqal, K. Ṣūrat al-'Arḍ, editor Kraemers, Leyden, 1938, I: 236.

(114) Ibid., 239.

(115) Ibid.

(116) Ibid., 243–44.

(117) Ibid.

(118) Abū Yūsuf, K. al-Kharaj, 51.

(119) Ibid., 50–51.

(120) Ibid, 50.

(121) Ibid.

(122) Von Kramer, loc. cit, 420.

(123) Al-Rabī' b. Ḥabib, Riwayat al-Ḍumam, II, fol. 55.

(124) Abū Yūsuf, op. cit., 50.

(125) Rasa'il Ikhwan al Ṣafa', Cairo, 1928, I, 215; al-Jawāliqi, al-Mu'arrab, Cairo, 1942,' 68; T. Fabd, Lcs corps de metiers, J.E.S.H.O,, 1965, 200; Ibn al-Muhannā, Ḥilyat al-Insan, Constantinople, 1917–19, 65.

(126) Waḍi'ah Taha al-Najrm, al-Jahiz wa al-Ḥaḍarah al-Abbasīyah, Baghdād, 1967, 212.

(127) Al-Jawāliqī, op. cit., 334–335.

(128) Ibid.

(129) Ibid., 235; Fraenkel, Die Aramaischen, Lcyden, 1886, 138.

(130) Ibid., 335, f.n.

(131) H. Kindermann, article Banū Asad, E. I. second edition, I, 683–84.

(132) A locality in the Arabian Peninsula, cf. Yāqūt. Mu'jam, Leipzig, 1869. IV, 1026, ff.

(133) Jāḥiẓ. K. al-Bayan wa al-Tabyīn, editor Sandūbī, Cairo, 1947, II, 66–67.

(134) Ibid., 67.

(135) Al-Qazwinī, Āthar, 222.

(136) Ibid.

(137) Jāḥiẓ, K. al-Bukhala', editor al-Ḥājirī, Cairo, 1963; 197.

(138) Waḍị'ah Ṭaha al-Najm, loc. cit., 212.

(139) Ibn Ṭūlūn, Naqd al-Ṭalib, Chester Beaty MS. 3317, fol. 50.

(140) Al-Qāsimī – al-'Aẓm, Qamūs al-Ṣina'at al-Shamiyah, Paris, 1960, II, 477–78.

(141) Anīs Frayḥa, Amthal al-'ammiyah al-Lubnaniyah, American University of Beirut, 1953, Vol. I, 72,127, 68; 11, 519, 581.