Muhammad 'Abdul Jabbār Beg

The Demand for and Supply of Slave Labourers

LIKE most of the countries of the Middle East in the Middle Ages, 'Iraq was a slave-holding society both preceding and during the 'Abbāsid epoch. The most usual means of obtaining slaves were the wars of conquest and the slave-trade. In pre-'Abbāsid times the flow of slaves into Arab countries was kept going mainly through wars, but when with the coming into power of the 'Abbāsids the wars of conquest came to a standstill, except for frontier raids against the Byzantines, the slave trade was the most important means for the supply of slaves. All wealthy persons (including the Caliphs), their relatives, high officials, the landlords, and the members of the bourgeoisie1 owned slaves. The existence of slave markets, Sūq al-nakhkhāsīn,2 in Basrah, Sūq al-Raqīq3 in Samarra, Dār al-Raqīq4 and Shāri Dār al-Raqīq5 in Baghdād, the hub of the 'Abbāsid Caliphate demonstrates in some degree the regular demand for and supply of slaves in Irāqī society.

An interesting account of one of the ways of capturing young Negro slaves by slave traders in Black Africa was recorded by al-Marwazi (c. 1130 A.D.) in these words, "Traders from the neighbouring countries visit the lands (i.e, the lands of the Zanj) with the object of hunting the children and young people. Accordingly, they repair to the meadows and hide in the woods carrying with them dates of which they drop a little on the children's playing ground. The latter pick up the dates, find them good and search for more. On the second day, they drop the dates a little further away than on the first day, and so they gradually go further and further and the children, whose minds are set on dates, follow them and when they are far (enough) from their parental houses, the traders leap on them, seize them and carry them away to their land."6

Most of the slaves in the 'Irāqī slave markets were, ethnically, of non-Arab origin, perhaps as a natural consequence of the ban imposed by 'LJmar on the enslavement of Arabs.7 An Arab, in the light of 'Umar's prohibition, may simply denote an Arabic-speaking person. Although, theoretically, the Arabs were above enslavement, we have contemporary evidence to suggest that Arab slaves were available, at least in the later 'Abbāsid period, beyond the confines of 'Irāq. The following sentence in the Qābūs-Nāma strikingly draws our attention. "As long as you can find a non-Arab, do not buy an Arabic-speaking slave; you can mould a non-Arab to your ways, but never the one whose tongue is Arabic."8 A dislike of buying Arab slaves in Tabaristan where they may have been available in considerable numbers, as noted by Kai Ka'us Iskandar, may be taken as a proof in support of the enslavement of some sections of the Arabs, and their sale in the slave-market by slave-traders.

There were slave-traders in 'Irāq, as elsewhere in medieval Middle East, known variously as al-nakhkhāsūn9, al-jallābūn, al-jallabīyūn10 and al-raqīqī-yūn.11 Although slave-traders were strongly disliked12 in society, the trade continued to thrive because of the high demand and also probably the lucrative nature of the trade. According to al-Sam'ānī, the word al-jallāb refers to a person who travels from place to place to buy and sell slaves and animals.13 Some of the merchants selling slaves and animals (al-jallāb) came from Mawsil, Baghdād, and some from Khwarizm14 The residents of the Slave Street (shāri' al-raqīq) in Baghdād were known as al-raqīqivūn who were either traders or brokers of slaves.15 Prominent among the raqīqiyūn were Abu Human Muhammad b. Muhabbib al-Raqīqī al-Dallāl and al-Hasan al-Asadī al-Raqīqī16 and well known among the jallāb were Abū Ayyub Sulaimān b. Ishaq b. Ibrāhīm b. Khalil al-Jallāb (d. 334 H./945 A.D.)17 of Baghdād, and Abū Sa'īd Aḥmad b. 'Alī b. Aḥmad al-Jallābī (471 H/1078 A.D.).18

Slaves of various races were available in Baghdād, viz., Slavs (al-Saqālibah),19 the Byzantines, the Armenians, the Turks, the Indians, and so on. The words al-Sūdān and al-Habashaḥ,20 like the Zanj, were loosely used to denote Negro slaves. One of the main supply routes of African slaves to Asiatic Arab countries was through the maritime merchants who traded with East Africa along the so-called Baḥr al-Zanj.21 The slave-trade was thriving especially in the countries around the Mediterranean. This trade flourished in Spain and in the Mediterranean harbour of Province, in Italy,22 in Greece,23 in Egypt, South Arabia, North and East Africa,24 as well as in Central Asia.25 "Samarqand was the greatest slave market for the supply of the best white slaves."26 In Europe, the Jewish27 merchants nearly-monopolised the slave-trade. Many of the slave-traders in the Middle East were Arabs,28 as their names suggest.

The slaves sold in 'Irāq came under the supervision of the muḥtasib who recommended that slave dealers should be just and honest persons because they were dealing with human merchandise, particularly the slave girls and the young slaves.29 The institution of ḥisbah, though, theoretically accorded the slaves certain human rights. They were to be treated fairly by the slave traders as well as by their masters. According to Islamic traditions, the owners of slaves were to offer good clothing and food, similar to their own, to the slaves under their custody,30 and the manumission of slaves was applauded as an act of piety. These traditions, although they humanised the institution of slavery, nevertheless did not abolish the institution of slavery itself; consequently, some Muslim societies until very recent times have been slave-holding societies.

However, the slave trade in 'Iraq seems to have reached the climax of its prosperity during the 3rd century H /9th century A.D. when there was a great demand for slaves as labourers in the domestic, industrial and agricultural fields. But certain decisive political events perhaps led to a decline in the slave trade in the 10th-11th century A.D. This was partly caused by the decline of the Caliphate itself, which resulted in a fall in the over-all material prosperity of the 'Irāqi society.

Slave Labour in ‘Iraqi Society

Slaves were employed in 'Irāqi society in a number of trades from domestic work to warfare. Writers and historians have described the types of work performed by different races of slaves. A writer of the eleventh century, Ibn Buṭlan, describes the various types of labour performed by slaves of different races in such a way that each race appears as if it had a particular ability to perform some specific work. "He who wants a nice slave-girl should take one from those of the Berbers. He who wants a store-keeper (khuzzān) should take one from the Byzantine (al-Rūm) slaves. He who wants a slave to nurse babies should take one from the Persians. He who wants a slave-girl for pleasure should take one from the Zanj women, and he who wants a slave-girl for singing songs should take one from Makkah."31

According to Ibn Buṭlān, Makkah had been a centre where singing girls were trained.32 Speaking about the training of an ideal slave girl, the author continues, on the authority of a slave-broker named Abu 'Uthmān, that a Berber girl should be taken from her country at the age of nine; then, she should be kept in Madinah for three years and three years in Makkah, then she may be taken to 'Iraq at the age of fifteen to be trained in cultural refinement (adab).33 Thus after going through all the stages of training, when she is sold at the age of twenty-five, she combines in herself the feminine qualities of the Medinese women, the delicacy of a Makkan and the cultural refinement of an 'Irāqī.34 Though these words are put in rather a theoretical style, they may be an echo of the practices of the slave-dealers during the 'Abbāsid period.

Continuing his statement about slaves, Ibn Butlan says, "He who wants a slave to guard his life and property should take one from the Indians and Nubians. He who wants a slave for (private) service (perhaps as a doorkeeper, or for domestic purposes) should take one from the Zanj and the Armenians, and whoever desires a slave for bravery and warfare should take one from the Turks and Slavs."35 All these statements reflect, perhaps, centuries-old experience of the slave-holding societies in the utility of slaves of different races.

We may now discuss the different social and economic functions of slaves in 'Irāqi society of'Abbāsid times under different sub-headings.

Domestic Slaves

By far the greatest slave-holders of the 'Irāqi society were the 'Abbāsid Caliphs themselves, who were the wealthiest and the most powerful men of the state. We may quote, from contemporary sources, a few statistics of the slaves employed by the Caliphs. The Caliph al-Muktafi (902-908 A.D.) is said to have possessed 10,000 slaves.36 In the 10th century A.D. the Caliph al-Muqtadir (908-932 A.D.), we are told, had 7,000 slaves (of different races) and 4,000 Slavs.37 The Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847-861 A.D.) was reported to have owned 4,000 slave-girls alone.38

Most of the slaves owned by the Caliphs and other members of the Galiphal family were employed in the palace as servants, concubines and body-guards. Similar was the case with the wazīrs,39 the amirs40 and other high dignitaries. Slaves employed for different jobs came to be known by different names. For instance, the slave who served wine or other drinks was known as al-skarābi,41 the slave who carried official letters was known as alrasā'ili,42 the slave who served in the harim43 was known as ḥarimī,44 and so on. Those working as porters were known as ḥammāl.45 Al-Sam'ānī46 and Marwazī47 mention a black slave arid a Zanji slave as porters. Besides the slaves employed in the Dār al-Khilāfah,48 slaves were owned by the wealthy traders and citizens. Hence the slave-women (qiyān) employed by high officials as well as by the well-to-do citizens worked as entertainers in such varied capacities as 'ūd-players, al-karra'āt (slave-dancers), blowers of the wind instrument resembling the oboe (al-zawāmir), and tanbur-players (al-ṭanburīyāt).49

Some of the slave women worked as cooks, mid-wives and foster-mothers.50 The Nubian slave-women were reputed to have been kind to babies as they were employed to nurse them. Some physicians preferred the Zanji women as foster-mothers to suckle babies.51

The loyalty of the slaves and their devotion to their masters were unquestioned, Hence we notice such a touching reference by a master to his missing slave as these words: "Who will now look after my ink-pot, my books, and my cups as he did? Who will fold and glue the paper? Who, in cooking, will make the lean rich? Regardless of the opinion of others, he always thought well of me. Loyal he ever remained when the trusted one failed."52

Slaves Employed in Handicrafts and Business Enterprises

Ibn Buṭlān recorded that slave women were employed in domestic work as well as as entertainers, but male slaves were employed in handicrafts.53 Sometimes the masters employed their slaves in such crafts as weaving and tailoring. The author of K. al-Aghānī54 speaks of a weaver ghulām55 owned by an Arab master. This statement may either mean that the slave was following the craft of weaving before his slavery and he continued to pursue the craft even after his enslavement, or simply that the slave was employed by his master to work in the productive craft of textiles. There are other independent illustrations of the employment of slaves in the textile industry. Al-Sulamī56 cites the case of Muhammad b. Ismā'īl al-Samarrī, a Sufi of black complexion, who in his early life was enslaved by a man who employed him in weaving khazz57 for a number of years. Jāḥiz mentions a special kind of cloth, al-khusrawanī,58 woven by slaves. It would appear from the evidence that the textile industry of 'Abbāsid 'Irāq had, among its workers, a number of slaves, perhaps a good number of them, from the people of servile status. Textile work, although important from the utility point of view, was one of the 'low' crafts, and the status of this craft as a demeaning trade perhaps arose partly from the employment of slaves in it. As far as the employment of slaves in the tailoring trade is concerned, we have one concrete illustration from the writing of the historian al-Mas'ūdī. It is reported that a slave tailor of the Āl al-Zubayr59 had to pay to his master a sum of two dirhams from his daily income as his ḍarībah.60 The phrase ḍarībatal-'abd, according to Lane, means "what the slave pays to his master, of the impost that is laid upon him."61 Although this single evidence is insufficient to enable us to form any possible judgment on the daily income of a slave tailor, nevertheless, it would seem that his daily income was at any rate higher than two dirhams a day in the 9th century A.D.

The bourgeoisie of the 'Abbāsid period formed a considerable section of the wealthy members of society. The works of Jāḥiz62 and those of al-Tanūkhī63 contain references to working slaves and slave-owning members of the society. Ibn al-Jassās,64 one of the leading members of the bourgeoisie in lOth century 'Irāq, had an undisclosed number of male and female slaves, of whom it is presumed some were employed in domestic work, while the rest were working along with their master in trading activities. According to Ibn Buṭān, the Byzantine slaves worked as store-keepers (khuzzan)65 in the stalls and shops of their masters. They were said to have been efficient in guarding the property of their masters. Commenting on the efficiency of the Byzantine slaves as store-keepers, Ibn Buṭlān adds, "The word benevolence (sakhā) is not traceable in their language"66—a phrase explained by a modern Arab editor to mean that the Byzantine slaves lacked the quality of benevolence in their temperament. Moreover, the Byzantine slaves were well known for their knowledge of the accuracy of different weights and measures.67 It may be deduced from the statement of Ibn Buṭlān that the Byzantine slaves were employed to work in jobs which needed (besides physical labour) a little intelligence. The reliability of the Rūmī slaves is also applauded by the same writer.68

Slaves Recruited for the Army

Besides being employed for domestic, industrial and commercial purposes, slaves were recruited into the army of the 'Abbāsid Caliphs. Although a powerful slave regiment was raised in the 9th century A.D., the existence of slave elements in the 'Abbāsid army can be traced to an earlier date. Al-'Azdī69 recorded that there were 4,000 Zanj70 slaves headed by a qā'id71 in the army of the provincial governor of Mawsil during the Caliphate of Abū Ja'far al-Mansūr (754-775 A.D.). This is however, the only known case of the employment of Zanj slaves in the army during the first decade of the 'Abbāsid Caliphate.

According to Ibn Buṭlān, the slaves of Turkish and Slav origin were the most efficient elements in combat and fighting.72 The Caliph al-Mu'tasim (833-842 A.D.) was reported to have purchased a number of slaves varying between 3,00073 and 4,00074 and raised his favourite slave regiment from Turks. The Turkish soldiery of the 'Abbāsid Caliphs, like the Janissaries75 of the later Ottoman Turks, were perhaps converted to Islam. Depending on the loyalty of the Turkish slave regiment, Caliph al-Mu'tasim transferred his capital from Baghdād to al-Samarrā', but soon the Turks interfered politically, and later they were involved in the assassination of the Caliph a-l Mutawakkil 'ala Allah.76 The Turkish element, from the days of al-Mu'tasim till the occupation of Baghdād (945 A.D.), meddled in 'Irāqī politics.

The slaves and slave-girls were also employed for espionage; for instance, Caliph al-Mahdī employed a slave-girl to spy on the activities of the wazīr Ya'qūb b.Dāwūd whose career was ruined on the intelligence report of the slave-girl.77 In contemporary Persia, 'Amr b. Layth al-Saffār (d. 902 A.D.) employed specially trained slaves to spy on the Persian nobles.78

The Black Slaves as Rural Labourers

Jāḥiz noted that the number of black slaves exceeded that of the white.79 We have evidence tending to show that a large number of these black slaves were employed by landlords to work in rural areas. Ṭabarī80 and Ibn Abi al-Hadīd81 recorded that the black slaves were employed to work on submerged lands in order to clean out the tracts of land that exude water and produce salt (sibākh). This seems to imply that in southern 'Irāq areas south of Basrah, in particular, often went out of cultivation because of their submersion under water, and also because of salination.

Reclamation of land, particularly that in the watery marshes, was undoubtedly a hard task for the slave-labourers whose working conditions in the marshes were not congenial to health, so we hear of the disease of the Zanj,82 probably malaria. These slave-labourers working in the marshes were described by a certain author as the slaves of the dahāqīn of Basrah and of their daughters;83 these slaves were not married and did not have any children.84 The slaves in the land reclamation service were part of the capital investment by the landowners on their vast landed estates. We do not definitely know when the black slaves were first employed for the purpose of land reclamation. Were the slaves doing simiiar work for the landlords during the Sassanid period? This question remains unanswered. However, the labouring slaves do not appear to have been satisfied with their masters, as may be seen from their sporadic uprisings both before and during the Abbāsid period. The first indication of unrest among slaves and their protest against their masters is recorded by al-Balādhuri and al-Wakī. A certain Shir-i Zanj was at the head of the first reported slave uprising near Furāt al-Basrah during the governorship of Hajjāj b. Yūsūf (d. 714 A.D.), but it was quickly suppressed.85 The uprising of Shir-i Zanj, the Lion of the Negro Slaves, took place, we gather from the text of al-Balādhuri, just before the revolt of Ibn al-Ash'ath,86 which occurred in 80-82 H./ 699-701 A.D.

We also hear of a second smal1-scale black slave riot (rather than a revolt) during the Caliphate of Abu Ja'far al-Mansur. This riot took place, according to Waki, in 143 H-/760 A.D. when Suwar b. 'Abd Allah87 was 'Abbāsid Qaḍī in Baṣrah. Jāḥiz, in his short description of this event, said that the total number of slaves taking part in this mini-revolt was forty. They put the people along the lower Euphrates to flight and also carried out a considerable massacre at al-'Ubullah.88 But the 'Abbāsid army easily quelled this minor revolt; the black slaves were beheaded, and their heads brought to the city for public display,89 presumably as a warning of what the consequences would be for those who threatened the de facto authority of the new regime of the 'Abbāsids.

The motives for these small scale outbreaks are not discernible, but the uprisings may have been caused by local grievances. The first two uprisings failed to bring about any change in the status of the working slaves and they were apparently not taken by the authorities with any seriousness. The failure may be attributed to the lack of any planned action and participation of only a limited number of slaves against a strong governmental authority. However, precedents were set and the toiling slaves needed only inspired leadership to wage a large-scale war.

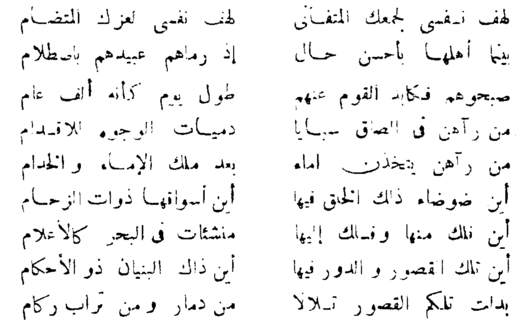

The well-known revolt of the slaves in 255 H./869 A.D. assumed a proportion never before witnessed in medieval Middle Eastern history. The leadership was provided by apolitical adventurer, 'Alī b. Muḥammad, who promised to emancipate the black slaves90 and to award them slaves for their service, a promise which may appear very simple, but which was, in fact, the most tempting promise that a leader could offer to his un-free servile followers. The leader seems to have made an elaborate and ambitious plan to establish a state on the ruins of the 'Abbāsid Caliphate with the help of the slaves of various races. The slave leader who was himself a free person and who was abused by his critics as "khabīth"91 (abominable), built a new capital of the slave kingdom at al-Mukhtārah92 and minted coins93 a symbol of the sovereignty94 of his domain. Then systematic raids were launched by the slave fanatics against such cities as Baṣrah,95 Wāsiṭ,96 'Abbādān97 and al-'Ubullah.98 Many people in these cities were enslaved99 by the rebel slaves, others were indiscriminately put to the sword. The casualty figure on both sides was estimated, perhaps with some exaggeration, at one million lives.100 The menacing war lasted for fourteen long years, a period sometimes alluded to as 'Ayyām al-Zanj101 (the days of the Zanj). It was one of the bloodiest revolts against the 'Abbāsid authority, which at times appeared unable to withstand the challenge.

The Zanj revolt was an expression of the organised might of the slaves who had been employed in hard labour. The medieval Shī'a writer, Ibn Abī al-Hadīd,102 ascribed the revolt to Shi'ism, a statement which gained credence due to the claim of the Zanj leader to be distantly connected with the 'Alid family.103 Even though religion may have played some part in the preparation of the revolt, the roots of this great event may lie in the hard fact of the social and economic104 miseries of the slave labourers.

Although Baṣrah was vulnerable to the organised attacks of pirates105 before the Zanj uprising, it was one of the worst hit cities during the war. Baṣrah and al-'Ubuilah, which were the chief ports connecting, through the 'Irāqī maritime trade, with the areas of the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and beyond, suffered damage beyond repair. An allusion to the extent of damage on Baṣrah and its population is to be found in a qaṣīdah of Ibn al-Rūmī.106 The continuous state of war also affected the agricultural prosperity of southern 'Irāq by disrupting the normal life of the peasants and farm labourers. The extent to which agriculture suffered in the war zones of southern 'Irāq may be deduced from the damage to the sugar plantations even in the distant area of Ahwāz107—where sugar production was proverbial.108 On the whole, the slave war had a disastrous effect on the material prosperity of 'Irāq, and it has been assumed with some justification that it was one of the major contributory factors in the decline of the 'Abbāsid Caliphate.109 What did the slaves achieve in the fourteen years' war (869-882 A.D.)? This is a moot question. The results of the war were disastrous in human and material terms, and its effect on the 'Irāqi economy in particular was extremely damaging. The slaves, notwithstanding their brave fighting throughout, lost the war in the end. There is no available evidence to suggest that there was any change in the status of the slaves in the post-war period in 'Irāq or elsewhere. Slavery was not abolished as a result of this internecine war, but survived as a social institution in 'Irāq and the neighbouring countries. The Zanj war, it seems, was an episode in 'Abbāsid history which did not produce any lasting impact on the status of the slave labourers. The slave trade continued to flourish even after the Zanj war.110 However, Belyaev, the well-known Soviet Orientalist, held a different view on the outcome of the Zanj war. He stated that, as a result of the war, "The slave-trade from Africa was very much reduced, as the demand was now limited solely to domestic slaves,"111 but to the present writer this statement appears to be an assumption which is not corroborated by any positive historical evidence.

Abbreviations

E.I. = The Encyclopaedia of Islam

J.E.S.H.O. = Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient

JRAS = Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

J.W.H. = Journal of the World History

Barthold, Turkestan = Turkestan down to the Mongol invasion.