Barbara Finster

[7] ISLAM GREW out of an urban civilisation and would be difficult to imagine without it. Crafts are part of urban civilisation: indeed, urban civilisation would not be possible without crafts. "Crafts can only take secure root in a town if the sedentary culture is anchored securely and of long duration,"1 the famous fourteenth century historian Ibn Khaldūn remarks in his Prolegomena. "Every perfect sedentary culture," he continues elsewhere, "provides intelligence, as it is a union of crafts."2 On the other hand, according to him "craft and science are the result of the human ability to think, which distinguishes man from the beasts...,"3 besides which, "...crafts and the practice [of crafts] always contribute to maintaining scientific norms, which are the result of this practice. Consequently every experience results in intelligence."4

A similar appreciation of crafts and craftsmen is expressed in the eighth treatise of the Pure Brothers (Ikliwān al-Ṣafā') of al-Baṣra, written in the tenth century. The basis, however, is a different one.5 We read: "...craft (al-ṣan'a al-'amalīya) comprises the creation of a form that a knowledgeable artisan has in his thoughts, and its realisation in concrete material. The product is the sum of form and matter...,"6 The greatest of artisans, however, is God: "Know, O brother," the Pure Brothers say, "that the skill in every craft consists in imitating the wise Creator who creates something from nothing, praised be He."7 The greater a craftsman's skill, the closer he is to God:

They say that God, the exalted, loves the craftsman who is skilful and accomplished [in his craft], and there is a tradition that the Prophet said: "Truly, God the exalted loves the craftsman who is God-fearing in his trade [8] .. .the Creator, praised be He, knows more than the scientists, is wiser than the wise, more skilful than the craftsmen and more excellent than the good. And everyone who improves himself by one degree moves closer to God."8

While the crafts are divided into several fields, there is no actual distinction between craft and art.

The Pure Brothers of al-Baṣra and Ibn Khaldūn distinguish between two kinds of craft: the simple craft and the compound craft. The interpretations of these terms, however, are different. The Pure Brothers write: "...the crafts are composed of two kinds: simple crafts and compound crafts. Simple craft is fire, air, water and earth, and compound craft exists in three kinds: mineral, vegetable and animal matter."9

Ibn Khaldūn, on the other hand, explains the two kinds of crafts in the following way: "...simple craft concerns the necessities of life, while compound craft belongs to the domain of luxury."10 According to him, the simple crafts are agriculture, architecture, tailoring, carpentry and weaving.11 Luxury crafts are, among others, painting, goldsmithing, and calligraphy. With the decline of urban culture, these will decline as well.12 There are also distinguished crafts that are so regarded because of their subject: obstetrics, the art of writing, the manufacture of books, singing and medicine.13

The Pure Brothers have a similar classification, based upon five criteria: the material used, the end product, the necessity, the overall usefulness and the skill as such.14 In another place they state: "Know, O brother, that there are crafts that are generated mainly by necessity, and others that serve and follow necessity, and others that aim at perfecting things. There are among the crafts some that are beautiful and decorative."15

All these ideas are based on a theoretical appreciation of the crafts and the craftsmen who were necessary in order for urban culture to flourish. The highest patron, as Ibn Khaldūn remarks, was the reigning dynasty:

It is the [reigning] dynasty that requires the crafts and their perfection... .Crafts that are not needed by the dynasty might be needed by other inhabitants of the city, but it would not be the same, as the dynasty is the main market.16

What is the evidence we have from the craftsmen themselves (who are not even mentioned in Ibn al-Faqīh's ranking), and what do we know about the craftsmen whose field was arts and crafts, as we see them? A precondition for our understanding is the point that Islamic society was divided into Muslims and non-Muslims, and that the rights of these two basic groups were very different.17 The desire for crafts and luxury goods was even present in the earliest years of Islam, although a pietistic tradition tries to deny this. The days of the earliest orthodox caliphs, for instance, witnessed a lively building activity with all its requirements.

Names of craftsmen of all times are known to us from sgraffiti and signatures. [9] They are found on the fragments of plain vessels, as for instance in Tulūl al-Ukhayḍir (eighth century):18 naṣr, as a decoration, stamped on the plain earthenware in Sāmarrā (ninth century, Plate I, 119), and also semidecorative around the rim of a small bowl from al-Ḥīra (Plate I, 220); min 'amal Ibrāhīm al-Naṣrānī mimmā.. .[ṣuni'a bi] l-Ḥīra [li-]l-amīr Sulaymā ibn amiī al-tm'minmīn "one of Ibraāiī the Christian's works, belonging to those which [woee made] in al-HḤīa for the Prince Sulaymaā, son of the Commander of the Faithful". The name of the master craftsman is used as a decoration in the centre of a bowl from Iraq or Iran (Plate I, 321): baraka li-ṣāḥibihi 'amal Muḥammad al-Ṣalā' (?), "blessings on its owner; the work of Muḥammad al-Ṣalā' (?)".

A beautifully made metal jug in the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad carries the inscription:22 mimmā 'umila bi-l-Baṣra sanat tis'a wa-sittīn baraka min ṣan'a Abī Yazīd, "belonging to that which was made in al-Baṣra in the year AH 69 (688 CE); blessings from the work of Abū Yazīd".

On fabrics, even those of state manufacture, we find the names of weavers, such as that of Muḥammad ibn al-Mu'alla on a piece of linen from the third century AH.23 Similarly, stonemasons and builders, sometimes one and the same person, inscribed their names into the well of the inn in al-Ṭalḥa in Iraq (eighth century):24 'amal Muḥammad Ja'far ibn....; or in the inscription near al-Ṭā'if:

This is the dam that was built for Mu'āwiya, the servant of God,

Commander of the Faithful; 'Abd Allāh ibn Ṣahr built it

By God's leave in the year 58 (AH; = 677 CE).

O God, forgive Mu'āwiya, the servant of God,

The Commander of the Faithful; make him strong and help him

And let the faithful rejoice in him.

This was written by 'Amru ibn Ḥabbāb.25

[10] On the façade of a mosque, the names of the architect and the carpenter can be mentioned besides that of the patron, the caliph, as was the case at Hārūn al-Rashīd's mosque in Baghdad.26

It is difficult to assess signatures preceded by kataba, "wrote". This may just be the name of the writer, as is possible in the inscription quoted above, but it can also mean "designed or made [by]". An instance of this is the inscription on the nilometer set in place in 247/861: ... wa-kalabahu Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥāsib,27 According to Ibn Khallikān, he built (waḍa'a) the nilometer at Mutawakkil's command.28

Besides these individual signatures there are also collective signatures, as for instance that of the workers of the city of Ḥims:29 "In the name of God etc... .the servant of God Hishām, the Commander of the Faithful, ordered the building (ṣan'a) of this city, and this is one of the things made by the people of Ḥimṣ (ahl Ḥimṣ), under the management ('alā yaday) of Sulaymān ibn 'Ubayd in the year 110 (AH, = 728 CE)." It is possible that the mosaicists from Egypt and Syria, who decorated the arcades around the Ka'ba with mosaics at al-Mahdī's behest, signed in a similar style.30 Al-Muqaddasī says: "...you can see their names on them (i.e. on the façades)."

These instances could easily be multiplied. What can we conclude from these signatures?

1. So-called master inscriptions can be found in every field; it is only a question of discovering them. This, in my opinion, invalidates the conclusion of Monneret de Villard expressed in the last chapter of his Introduzione allo studio dell'archeologia islamica. He is of the opinion that master inscriptions only appear from 'Abbāsid times onward. His explanation is that in Umayyad times the artisans were recruited mainly from a Christian background, which is true for a large number of them. He suggests that they would not have signed their works and that the signing of works only came into fashion with the more general process of Islamisation. It is obvious, however, that Christian craftsmen showed just as little reluctance to sign their works as did their Muslim colleagues.

2. Everybody signs, be he architect or workman. Where ceramics are concerned these names appear to be literally just proof of manufacture. This can be seen from simple household articles, and in any case exactly the same phenomenon exists today. An artist's pride is probably expressed on those pieces intended to carry a blessing (baraka). Grube's assumption that the names on the Sāmarrā ceramics could be explained by patronage or collectors' spirit rather than by the "individual quality of the object" can be countered with the fact that even simple household articles are signed.31 Besides objects on which "baraka from Abū Yazīd's work" is wished, as on the bronze jug mentioned above, there are others the inscriptions of which testify to a certain garrulousness that we also encounter [11] in other fields. On hundreds of sgraffiti God is asked for forgiveness: Allāhumma ighfir li..., ["O God, forgive...."]; ghafara Allāh li..., ["May God forgive...."], etc. The self-confidence of those workers who signed their works does not have to have been greater than that of the workers in general.

3. It is noticeable that many inscriptions, in particular those on buildings. but also on woven and ivory pieces, contain one set phrase even more frequently than 'amal or min ṣan'a. This phrase is 'alā yaday or mimmā jarā, meaning "at the hands of" or "under the management of", and always comes before the other phrases. This expression appears in the abovementioned inscription on the building in Qaṣr al-Khayr al-Gharbī, but also on a lidded box from Madīna al-Zahrā in Spain made in AH 965. After the usual mention of the commission we read: 'alā yaday Durayy al-Ṣaghīr.32 This Durayy al-Ṣaghīr began his career as a slave and then moved up until he became chamberlain and governor. This supervisor or, better, manager played such an important role that his name appeared next to that of the patron who gave the commission. Another instance of this is on the mosque in Rayy, built around 158/774, where "'Ammār ibn Abī l-Ḥaṣīb" appears next to al-Mahdī's name.33

The chief supervisor of the construction of the mosque in Damascus, for instance, was Sulaymān ibn 'Abd al Malik, al-Walīd's brother and successor. For the buildings in al-Ramla that Sulaymān himself commissioned, Baṭrīq ibn Nahā, a Christian patriarch, held this office.34 Especially under the 'Abbāsids we frequently find mawlās or clients as supervisors, but it is not possible to conclude a rule from these instances.

There are little anecdotes telling us what the duties of these supervisors were. About Sulaymān, for instance, it is said that after the work was finished he took every single leftover nail back to the treasury. In addition they had a certain artistic responsibility. When al-Walīd ibn 'Abd al-Malik inspected the mosque in Medina, he asked his cousin why he had not decorated the ceiling as beautifully as the central aisle toward the miḥrāb. The answer was that this would have been too expensive.35

As we can see from some inscriptions, the office of supervisor also brought with it a certain dignity. Thus, for example, at the end of an inscription in Mecca dated 194/809 it says: 'alā yaday Abī Isma'īl ibn Ishāq al-Qāḍī aṭāla Allāh baqā'ahu wa-adāma 'izzahu wa-karamātahu, "At the hands of Abū Ismā'īl ibn Isḥāq the judge; may God lengthen his time on earth and let his glory and his generosity continue."36 Although the person mentioned here is a qāḍī, we do find another example, in a mosaic inscription in Medina, which says: 'alā yaday Ibrahīm ibn Muḥammad aṣlaḥahu Allāh, "may God prosper him."37 In later times the managers of the ṭirāz manufactures in Egypt had a particularly high status, namely that of a foreign ambassador.38

These questions, however, lead us into the subject of the organisation of groups of craftsmen, about, which we know a fair amount from reports of the large commissions of construction work in Damascus and Medina, etc., but in particular from the foundation of the cities of Baghdad and Sāmarrā. [12] According to al-Ya'qūbī, during the building of Sāmarrā in 836 al-Mu'taṣim ordered that:

...engineers should come to him. He said to them: "Chose the best spot. Chose a number of places for palaces." He commissioned all the men around him to build one palace each. He ordered Khāqān Urtuj Abū l-Fatḥ ibn Khāqān to build Jawsaq al-Khaqānī, and 'Umar ibn Faraj to build a palace named al-'Umarī.39

Thus the finished palaces were named after the supervisors, who actually were not trained for this sort of work at all. Later 'Alī ibn Yaḥyā ibn Abī Manṣūr was given a post that:

...also included building and repair works. The next caliphs al-Musta'īn and al-Mu'tazz confirmed him in this post. Al-Mu'tazz commissioned him to build the Qaṣr al-Kāmil and gave him 5000 dīnārs and a plot of land when he had finished it. Al-Mu'tamid left him in this office and asked him to build al-Ma'shūq and he built the major part for him.40

The fact that they were not qualified should not overly surprise us, as the viziers at the 'Abbāsid court were frequently appointed without having any previous experience. Furthermore, they would have architects and engineers by their side. Names of architects survive not only from 'Abbāsid times, but also from the Umayyad period. The plan for the mosque of Damascus, for instance, is said to have been drawn or designed (khaṭṭa) by a certain Abū 'Ubayda ibn al-Jarrāḥ, who also planned the mosque of Ḥimṣ.41

Our knowledge of the events during the foundation of the cities of Baghdad and Sāmarrā is more detailed. For the construction of Baghdad, al-Manṣūr called in engineers and architects (muhandis and bannā'), people who had building experience and surveyors, to draw a plan for the city.42 The men came from Syria, Jibāl, Mosul, al-Kūfa, Wāsiṭ and al-Baṣra. The engineer or architect, Ḥajjāj ibn Arṭāt, and men from al-Kūfa supervised the planning. The names of four more architects have come down to us. Each of these was responsible for one quarter of the round city. They always had supervisors or managers at their side who ensured that everything went smoothly. Furthermore, the architects could be responsible for individual buildings, such as Ḥajjāj ibn Arṭāt, who built the Great Mosque.

The individual workers were under the supervision of further inspectors, one of whom was Abū Ḥanīfa, who had to supervise the manufacture of bricks.43 According to al-Khaṭīb, al-Manṣur did not begin with the construction of the city until he had assembled many thousands of workers and craftsmen. "He wrote to every town that they should send whoever knew anything about building," just as Sa'd ibn Abī Waqqāṣ had earlier called all the people of the Sawād for the construction of the city of al-Kūfa.44

For the construction of Sāmarrā, the caliph wrote asking for (kataba fī):

...workers, masons, craftsmen, smiths, carpenters and other craftsmen. He also ordered teak and all other building woods, beams from al-Baṣra and its environs, from Baghdad and all the Sawād, furthermore marble workers and marble slabs from Anṭakya and every coastal town in Syria—and they found marble workshops in Latakiya and elsewhere.45

Ernst Herzfeld uses the (Greek) term "liturgy" for this procedure, after C.H. Becker. This system had been in use ever since the earliest times; according to Herzfeld [13], it was used for the construction of Pasargadai. Al-Walīd ibn 'Abd al-Malik employed it to build his mosques, as we read in al-Muqaddasī: "Al-Walīd assembled qualified craftsmen from Persia, India, the Maghrib and Byzantium...not counting the tools and mosaics sent to him by the Byzantine emperor."46 Papyri found in Aphrodito in Egypt, which contain correspondence between the prefect of the province and the governor, shed light on the procedure. Thus the province Aphrodito had to send craftsmen as well as tools and nourishment for them. We read, for instance, "... pays the wages and the upkeep of a sawyer for his work in the mosque in Damascus for six months...."47

This system of liturgy was probably not invented by Muslims in this exact form. It is more likely that it was copied from the Byzantine Empire, in respect of the recruiting of the workers as well as their upkeep. Here again the Muslims took on an existing system and exploited it skilfully.48 However, this system requires a strong central power, without which it could not function. As Ibn Khaldūn says:

...the monuments of a given dynasty are proportional to its original power....they can only be created if many workers are present, as well as concerted activity and co-operation. If a dynasty is great and all-embracing, with many provinces and subjects, if workers are numerous and can be assembled from every part and region, then even the greatest of buildings can be created....49

Indeed, with the decline of the caliphate and the succession of the smaller states, this system was no longer possible, except on a much smaller scale for the new potentates. In addition, they could engage craftsmen from other regions, much as nowadays. In this way variation and internationally were guaranteed.

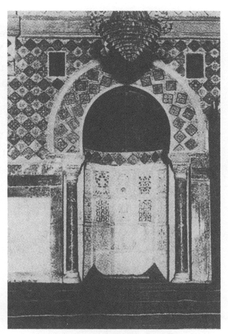

Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn took craftsmen from Iraq with him to build his mosque, and he possibly even engaged experts for lustre faience.50 Similarly, in about 836 the Aghlabid ruler Ziyādat Allāh ordered lustre faience from Iraq, together with a specialist who could then manufacture more faiences in al-Qayrawān (Plate II, 4).51

What were the consequences of this liturgy system for art and works of art? According to Herzfeld and later K.A.C. Creswell, the development of Islamic art in general can be explained through this system. Umayyad art is purely the result of cooperation between craftsmen of different origins whose workmanship is easily recognisable, for instance on a building. Conversely, however, works of art of this kind have to be instances of early Islamic art, as Herzfeld postulates. A perfect example is the palace of Mshattā in Jordan with its famous façade. Herzfeld proves that craftsmen from Diyārbakr were responsible for the elevations, an Iraqi craftsman for the planning, etc. The explanation of the differences in style within the decoration of the façade can also be found in the different groups of craftsmen (Plate II, 1 and 2).52

[14] This assumption becomes more problematic with regards to the Sāmarrā ornaments, where the three "styles" can hardly be explained as being the work of different groups of workers.53 There was undoubtedly an exchange of ideas and techniques that had not previously existed. Specifically Iraqi vaulting techniques and construction of arcades are suddenly found in desert palaces in Syria, while typically Sasanid stucco decoration spreads westward. We can even observe ground plans travelling, as for instance in the palaces of Mshattā or Shu'ayba/al-Baṣra.54 The exchange of shapes, in stucco decoration as well, proceeded not only from east to west, but also, as the stucco of Iṣfahān, Nā'in and Balkh shows, from west to east (Plate II, 3).55

However, the difference between the various styles is due not only to different groups of craftsmen, but perhaps rather to the respective models. Thus it is noticeable that some of the plants in the mosaics of the Dome of the Rock have lower parts in an "antique" style, whereas the upper parts appear "Sasanid", but even so it does not appear as if they had been created by different masters (Plate I, 4). Similar observations can be made concerning the stucco decorations in Tulūl al-Ukhayḍir, where there are incompatible pieces of two styles among the fragments. It is not likely that two different schools were at work in Ukhayḍir. Besides, it appears that the "Sāmarrā I style" can only be understood in connection with "Sāmarrā III", according to Herzfeld, as the capitals in al-Raqqa demonstrate.56 However, this leads toward a further and more difficult topic of style in Islamic art.

What is characteristic and permanent in Islamic art, however, is its internationally: the movements of motifs, techniques and craftsmen. This meant that even those regions that are situated on the periphery, such as some parts of North Africa and South Arabia, possess excellent works of art. In fact this exchange is alive in all fields of life, religion, science and culture.

Plate I:

1. shards from Sāmarrā (after the Catalogue, Hetjens Museum); 2. bowl belonging to Sulaymān ibn 'Abd al-Malik (after Grohmann); 3. bowl, presumably from Iraq, ninth century (after the Catalogue, Hetjens Museum); 4. mosaic, Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem (after EMA2, I).

Plate II:

1. Mshattā, façade (after EMA2, II); 2. Mshattā, façade (after EMA2, II); 3. miḥrāb, Great Mosque, Nā'in (after PKG 4); 4. miḥrāb, Great, Mosque, al-Qayrawān (after PKG 4).

1. 2. Mshattā, façade

3. miḥrāb, Great Mosque, Nā'in

4. miḥrāb, Great Mosque, al-Qayrawān

1The following paper is intended to provide an overview of the material available. Sources will be quoted in translation where possible. U. Monneret de Villard has studied the early craftsmen in detail in his Introduzione allo studio dell'archeologia islamica (Venice and Rome, 1966), and has provided an exhaustive bibliography for the subject. For later times, the following works are recommended: L.A. Mayer, Islamic Metalworkers and their Works (Geneva, 1959): idem, Islamic Armourers and their Works (Geneva, 1962); idem, Islamic Woodcarvers and their Works (Geneva, 1958); idem, Islamic Architects and their Works (Geneva, 1956); Ibn Khaldūn, The Muqaddimah: an Introduction to History, trans. F. Rosenthal (New York, 1958; Bollingen Series, XLIII), II, 349.

2Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 406.

3 Ibid., II, 347.

4 Ibid., II, 406.

5See Y. Marquet, art. "Ikhwān al-Ṣafā'" in EI2.

6Ikhwān al-Ṣafā', Rasā'il Ikhwān al-Ṣafā' (Beirut, 1376/1957), I, 277.

7Ibid., I, 290.

8 Ibid. See also Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 351: The value of every man is in what he knows.

9Ikhwān al-Ṣafā', Rasā'il, I, 280.

10Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 346.

11 Ibid., II, 355. The Pure Brothers mention agriculture, weaving and building as belonging to the group of necessary crafts; Rasā'il, I, 284 n. 14.

12Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 352. Cf the Pure Brothers, Rasā'il, I, 285: "... and as regards the crafts of what is beautiful and decorative, they include brocade weaving, silk weaving, perfume manufacture and similar things."

13Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 355.

14Ikhwān al-Ṣafā', Rasā'il, I, 287. See also G.E. von Grunebaum. Der Islam im Mittelalter (Zurich and Stuttgart, 1963), 278.

15Ikhwān al-Ṣafā', Rasā'il, I, 284.

16Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 352.

17Concerning these questions see von Grunebaum, Der Islam im Mittelalter, 227; for modern-day Arabia see Taqi ed-Dīn al-Hilālī, "Die Kasten in Arabien," Die Welt des Islams 22 (1940), 102ff.

18 Baghdader Mitteilungen, 8 (1976), Fig. 53a.

19Islamische Keramik, Catalogue of the Hetjens-Museum (Düsseldorf, 1973), no. 18.

20A. Grohmann, Arabische Paläographie, II (Vienna, 1971), Table XIV, 2; this probably refers to Sulaymān ibn 'Abd al-Malik and not to Sulaymān, the son of the caliph al-Manṣūr.

21 Catalogue of the Hetjens-Museum, no. 24; E.J. Grube, Islamic Pottery of the Eighth to Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection (London, 1976), no. 7.

22 J. Fehervári, Islamic Metalwork of the Eighth to Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection (London, 1976), Table I A.

23 E. Combe, J Sauvaget, and G. Wiet, eds., Répertoire chronologique d'épigraphe arabe, I (Cairo, 1931; hereafter RCEA), no. 747.

24 Baghdader Mitteilungen 9 (1978), Table 19c.

25 Grohmann, Arabische Paläographie, II, Fig. 44.

26 K.A.C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Oxford, 1940; hereafter EMA1), II, 32.

27 RCEA, I, nos. 461, 472; see also no. 8,

28 See EMA1, II, 303-304.

32E. Kühnel, Die islamischen Elfenbeinskulpturen, VIII.-XIII. Jahrhundert (Berlin, 1971), Table XVII, 27.

33P. Schwarz, Iran im Mittelalter (repr. Hildesheim and New York, 1969), 754,

34Ibn Shaddād, Al-A'lāq al-khaṭīra fī dhikr umarā' al-Shām wa-l-Jazīra (Damascus, 1375/1956), 62; al-Balādhurī, Futūḥ al-buldān, ed. M.J. de Goeje (Leiden, 1866), 143; Monneret, de Villard, Introduzione, 304.

35Al-Samhūdī, Wafā' al-wafā bi-akhbār dār al-muṣṭafā, ed. M. 'Abd al-Ḥamīd (Cairo, 1374/1955), 512, 524.

36RCEA, I, no. 88.

37Ibid., II, no. 83.

38M.A. Marzouk, "The Tirāz Institutions in Medieval Egypt," in Festschrift K.A.C. Creswell: Studies in Islamic Art and Architecture (Cairo, 1965), 157ff.

39 Al-Ya'qūbī, Kitāb al-buldān, ed. T.G.J. Juynboll (Leiden, 1861), 32; EMA1, II, 229; E. Herzfeld, Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra, VI (Hamburg, 1948), 94-95.

40Yāqūt, Irshād al-'arīb ilā ma'rifāt al-'adīb, ed. D.S. Margoliouth (London, 1929), V, 474-75; EMA1, II, 364.

41Ibn Shaddād, Al-A'lāq al-khaṭīra, 48; supervising the work: Yazīd ibn Tamīn, 'Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Salmān, 'Ubayd ibn Hormuz. See also Monneret de Villard, Introduzione, 304.

42Al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Ta'rīkh Baghdād (Cairo, 1931), I, 70-71; EMA1, II, 6; E. Reitemeyer, Die Stadtgründungen der Araber im Islam (Munich, 1912), 53.

43Al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Ta'rīkh Baghdād, I, 78; Monneret de Villard, Introduzione, 305.

44Al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Ta'rīkh Baghdād, I, 78; M.H. Zotenberg, trans., Chronique de Tabari: Traduction sur la version persane de Bel'ami (Paris, 1867-74), 401.

45 Al-Ya'qūbī, Buldān, 32; EMA1, II, 220; Herzfeld, Ausgrabungen von Samarra, 97.

46 E. Herzfeld, "Die Genesis der islamischen Kunst mid das Mscliatta-Problem," Der Islam 1 (1910), 27ff.; al-Muqaddasī, Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī ma'rifāt al-aqālīm, ed. M.J. de Goeje (Leiden, 1877), 158; K.A.C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture: Umayyads, A.D. 622-750 (Oxford, 1969; hereafter EMA2), I, 151; see also Ibn Asākir, Ta'rīkh madīnat Dimashq wa-dhikr faḍlihā, I, ed. S. Munajjid (Damascus, 1373/1954), 25-26.

47H.J. Bell, "Translations of the Greek Aphrodito Papyri in the British Museum," Der Islam 3 (1912), 373; EMA2, I, 151-52.

48EMA2, II, 373 n. 11; Monneret de Villard, Introduzione, 305.

49Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, II, 356.

50R. Schnyder, "Tulunidische Lüsterfayence," Ars Orientalia 5 (1963), 49ff.

51EMA1, II, 314.

52EMA2, II, 596ff.; Herzfeld, "Genesis," 105ff. Herzfeld ascribes the first fields in the triangle A-E to Syrian master craftsmen, D-L to Egyptians, M-T to craftsmen from Diyārbakir and Iraq. Creswell recognises Coptic workers in the triangles A-L, while the remaining triangles point toward Persian influence. Trümpelmann, on the other hand, assumes Syrian artists, who work in the antique tradition, on the left half of the façade, and Iraqi artists on the right side; see K. Trümpelmann, Mschatta (Tübingen, 1962).

53E. Herzfeld, Der Wandschmuck der Bauten von Samarra und seine Ornamentik (Berlin, 1923).

54EMA2, II, 578; Sumer 28 (1972), 243-44 (Arabic section).

55Not yet published pieces from the excavation of the Masjid-i Jum'a in Isfahān, miḥrāb of the mosque in Na'in: most remarkable are the lotus flowers in the Mediterranean tradition on the miḥrāb, L. Golombek, "Abbasid Mosque at Balkh," Oriental Art 15 (1969).

56M.S. Dimand, "Studies in Islamic Ornament, 1," Ars Islamica 4 (1937), Fig. 42-46.