Contentious Issues

The Moral Sentiments of Community Life

“I DRIVE DOWN THE INTERSTATE, and there are billboards advertising all these places with totally nude dancing. Just going down the interstate! So now you’ve got a six-year-old saying, ‘Hey dad, what does that mean, totally nude?’ I’m concerned where all this is headed. Or has already gone—this ‘anything goes’ mentality.” This is the moral corruption that worries Gene Fazio, a high school basketball coach in his early fifties who lives in a riverfront town of ten thousand. On all sides, the high school is surrounded by well-kept working-class bungalows, and down the street a few blocks are the small manufacturing plants and retail stores that have been operating here for more than a century. It isn’t just the blatant sexuality that bothers Mr. Fazio. There just seems to be something wrong with the world these days.

“The moral climate of our country has decreased precipitously over the last thirty or forty years,” complains Rev. Terry Thompson, a sixty-three-year-old pastor of a fundamentalist congregation called God’s Word Bible Church in a town of twenty-five hundred. On any given Sunday, nearly a quarter of the town’s population hears him preach. He works closely with two other fundamentalist preachers in town who share his beliefs. The mainline Methodist and Lutheran congregations also lean heavily toward conservative convictions about morality. “I graduated from high school in the 1960s,” Rev. Thompson explains, “and the teachers’ main complaint then was chewing gum and talking in class. We’ve seen that change tremendously. Kids are no longer taught that there are absolutes as far as right and wrong is concerned. There’s grave danger in the constant teaching that we are nothing more than glorified animals. There’s nothing special about us then. Kids have to find their sense of being special somewhere else. And very often for young girls and boys it’s in sexual fantasies.”

Living in a small town, it is easy to feel beleaguered by the outside world. The town is like a haven, but one that is threatened, a life raft adrift in a sea of change over which it has no control. Nobody in the town makes decisions that matter in the wider world. Influential business tycoons in New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and Hollywood make those decisions, which are crafted by media moguls and government lawyers who have little understanding of small-town America. Meanwhile, a local business dies, a family moves away, a homecoming queen gets pregnant, and a promising athlete succumbs to a meth addiction. Even if the town is growing, it seems insignificant compared to the tens of millions who populate large cities. So a person thinks about all the forces over which they have little control and seizes on the few where some grasp is still possible.

“One of the prophecies in the Bible is that in the latter days, you will see people doing what is unnatural, such as women turning to women, and men turning to men. That was almost unheard of when I was a child. But today it’s very prevalent.” This is a man in his late sixties who lives in a town of nine hundred surrounded by cornfields. “America has fallen away from the Bible,” he asserts, pointing to an epidemic of greed, dishonesty, and a lack of caring. “I think the United States is going to see some serious consequences.” He fears these problems are spreading out of the cities and now contributing to the demise of his own community.

A middle-aged couple living in a town of fifteen thousand that has become racially and ethnically diverse in recent years sees “a decline, a disintegration of the family.” The wife points to kidnapping, molestation, pornography, and sexual deviation as evidence. The husband describes the decline as a problem of people being too tolerant about moral issues as well as experiencing “real confusion” about right and wrong. He anticipates increasing “havoc in our system.”

Since the late 1980s, social observers have argued that a cultural war is increasingly evident in US values. On one side are self-styled progressives—liberals who believe that values are contextual, and moral decisions must be made with a relativistic understanding of varying circumstances and constraints. On the other side are the traditionalists—conservatives who believe in firm distinctions between right and wrong, and whose convictions are often understood as being grounded in divine revelation. Progressives live in places like San Francisco and New York City; conservatives reside in small towns like Tyndall, South Dakota, and Brinkley, Arkansas.1

Of course, many of the stereotypical notions about a US culture war are overstated—and some are plain wrong. It is not true, for example, that the most outspoken traditionalists are country bumpkins. Many are well-educated, thoughtful, and articulate spokespersons for conservative moral principles. They live in upscale suburbs, teach at elite universities, earn handsome salaries as corporate executives, and express their opinions on popular radio and television programs.

Most of what we know about contentious culture war issues comes from surveys that broadly map national opinion as well as investigations of movement activists who mobilize money and influence on behalf of political candidates and legislation. While some of this research has been conducted in small towns, little of it has considered how living in a small community shapes the ways in which moral sentiments are expressed. As a result, it is easy to imagine that small towns are simply bastions of moral conservatism—or that they are as fraught with cultural conflicts as anywhere else.

What we know from decades of sociological theorizing is that a community’s sense of itself is closely intertwined with its perceptions of good and evil. Communities reinforce their defining values by mobilizing against external forces that are deemed to threaten the community’s vitality. Residents identify positions on social issues that they believe to be shared in their community—and in talking about these positions reinforce the sense of indeed being a community. Townspeople define themselves over and against strangers, deviants, and alien lifestyles of which they disapprove.

It is from this theorizing that notions about the peculiarities of small towns arise. A town that promotes and defends conformity can be a dangerous place for someone who inadvertently deviates. An African American who strays into an all-white community of southern racists can be in big trouble. So can a gay person who stops for gas in a town of bigoted rednecks. The enforcers of community values may be the local sheriff, a popular preacher, or a vigilante committee.

But the stuff of which scary lore about small towns is made fails to take account of the fact that small towns are well integrated into the national culture. It is precisely this integration—the ease with which interaction occurs between residents of small towns and people as well as ideas from other places—that sparks concerns about billboards advertising nude dancing, stories of child molestation, and evidence of an “anything goes” mentality.

People who live in small towns understand that whatever the circumstances may have been that led them to live where they do, their communities are in a tenuous position with respect to the wider culture. On the one hand, these small communities reflect the nation’s larger economic and demographic trends, and participate in the same environment of media and entertainment. On the other hand, living in a small town is tantamount to going against the grain, and thus having reasons to think and behave differently from people elsewhere.

The net effect of this ambiguity is to inflect discussions of contentious moral issues with special significance. How a person thinks about abortion and homosexuality—or the position one takes toward teaching evolution or combating drugs—is partly a way of defining oneself as a member of a community. Moral convictions convey the shared sense of what is good about a community. They suggest how a small town may be threatened, and what should be done to preserve its cherished way of life.

A SENSE OF DECLINE

Hardly anyone we talked to in small towns felt that the moral life of the United States is improving. To the contrary, they were pretty sure it was declining. That response is probably not surprising. National polls suggest that many Americans are concerned about moral decline. People may be especially likely to feel this way living in a community that prides itself on preserving the past—a community in which the population is declining. A few of the people we talked to drew a direct association between the two kinds of decline, arguing, for example, that their town would be better off if people nowadays were obeying the Bible.

But the connection between one’s community and a person’s sense of moral decline is usually not this direct. Instead, the link must be understood by considering what exactly the problem is when someone says morality is declining. Usually it is something about the family, including promiscuity and divorce, or how children are being raised, the work ethic is declining and people are becoming greedy and materialistic, or people are focusing too much on themselves and not enough on others. If we recall what people in chapter 3 said they like best about their communities, these specific kinds of decline will sound familiar. They are precisely the values that people appreciate most about their communities. Inhabitants regard their small towns as places where families are strong, children can be raised properly, people work hard and are not materialistic, and residents care more about others than themselves. If these values are in decline, the decline is a threat to what people in small towns hold dear. A few examples will show what I mean.

Denise Hedron, an accountant who lives with her husband and two teenage daughters in a Sunbelt town of eight hundred, says the worst moral problem in the United States is people not being willing to work hard. It is understandable that she might feel this way. She grew up on a farm, helped with chores after school, and worked her way through college. But when asked to say more about her views, she asserts that the underlying problem is “the destruction of marriages,” which she traces back to the permissiveness of the 1960s and 1970s. “People getting pregnant and not getting married, [and children] not having a father in the household to provide direction and leadership,” she says, are the reasons children do not learn to work hard. “I know people don’t want to hear it, but when you look at the cold hard facts, you see that one of our biggest moral failings as a country is letting people feel it’s OK to divorce and remarry and have sex and just do whatever makes you feel good. It’s ruining our children.” She also connects the dots between this general problem and her community. “I look around our community and I see the children who are struggling in our school system” she explains, citing these children as an instance of the failure of marriage. She adds that her church’s youth group is trying to step into the gap and teach children better values. Sometimes even this is a struggle, she says, because you always have to avoid “stepping on someone’s rights.”

The basketball coach I mentioned earlier who is troubled by billboards advertising nude dancing illustrates a somewhat-different connection between moral concerns and community values. At one level, he draws a fairly simple contrast between corruption in cities and goodness in his small town. The billboards offer nude dancing in Saint Louis and Chicago, he says, whereas “we don’t have those kinds of whatever you call them—clubs—in this town.” At another level, nude dancing is just a symptom of a larger problem that again is more acute elsewhere, he feels, than in his community. “I would categorize this as a sharing community,” he observes, noting that the largest company in town is locally owned and gives money back to the community. “They aren’t outsiders taking and not returning,” he explains. He also believes there is a broader “downward spiral” in our country. Drugs are beginning to show up where he teaches, and he figures guns will be next. Ultimately, he thinks the root problems are “bad parenting” and “the greed factor.” These are the precise opposite of the good parenting and sharing that he feels have made his community strong.

It is perhaps easy to read comments like these and conclude that smalltown residents are overly pessimistic, maybe fearing too readily that their way of life is eroding. If they had a better grasp of the wider world, a critic might argue, they would realize that things are not so bad. A different interpretation, though, is possible. Set aside the fact that people are often nostalgic about community and a family life that never really existed, at least not in as rosy a way as they imagine. Consider instead the change that many residents in small towns have in fact experienced. They grew up in small towns or urban neighborhoods that seemed warm and comforting, perhaps because they were children and not faced with the harsh demands of adult life. For whatever reason, they wanted to replicate that sense of living in a secure friendly environment. They stayed in a small town or moved to one. But they sacrificed something as a result. The big company they could have worked for was not located there. The corporate ladder they could have climbed required them to move from city to city. Their childhood friends and siblings mostly chose that route, as have their children. Daily life now consists of friends and neighbors who share their values, and news from the outside world, commercials, and television programs about people who do not share their values. Little wonder that they feel the society is not going in a good direction. “It’s not just the breakup of the family,” notes one man, serious as he thinks that is. “We as a culture, as a community, as churches, as governments aren’t doing things like we should.”

The point is not that moral decline is felt more acutely in small towns than anywhere else or only because of living in a small community. There are many reasons to feel that things are not what they used to be—including promiscuity on television and drugs on the street, not to mention a middle-aged person’s own fading sense of youthful vigor. The point is rather that moral decline takes on distinct meanings in small communities. What a person cherishes there—the chance to raise a family, feel secure, and feel cared for by neighbors and friends—is precarious under the best of circumstances. A sense of broad moral decline hits home. It makes one’s community all the more important.

PROTECTING THE UNBORN

Besides general concerns about moral decline, residents of small towns closely follow the contested issues of the day. Just as it is in cities and suburbs, abortion is one of the topics that surfaces repeatedly when people in small towns discuss moral issues. Especially if they are Catholic or members of a conservative Protestant church, and also are deeply invested in raising children, they are likely to stand firmly on the prolife side of the issue. A Catholic woman in her thirties who is a full-time mother is a good example of the thinking that goes into taking this position. Hers is by no means a formulaic response that could easily be reduced to slogans. “I am an independent person,” she says, “and I don’t want to hear that I don’t have a choice about what I do with my own body.” And yet she is opposed to the prochoice position because she is convinced that abortion is devastating to women. The reason, in her view, is that it is contrary to women’s nature. “Women have a sense of being a mother. Maybe they are a twenty-one-year-old who says, ‘I do not want to have kids.’ But they go along, and the doctor tells them they will never be able to have kids. That woman is going to mourn.” By the same token, she says, “When a woman chooses to have an abortion, to end a life, there is a strong emotional part there—something that a woman has to deal with for the rest of her life.” It is for this reason, the woman explains, that her feelings about abortion definitely influence how she votes.

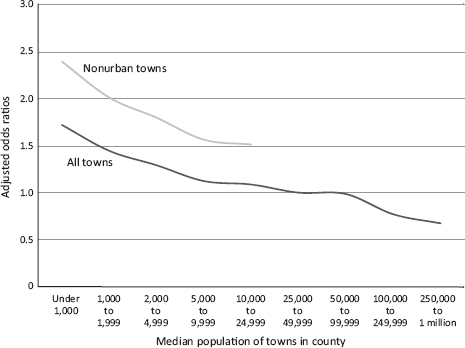

When asked what the most serious or troubling moral problem in the United States is, people in small towns more frequently than not say it is abortion. Some of the reason that opposition to abortion is strong in these communities is that residents of small towns differ from those in larger towns and cities in ways that relate to attitudes toward abortion, such as age, gender, education, and region. But taking these factors into account, where a person lives still appears to make a difference (see figure 8.1). Compared to someone living in a metropolitan county in which the median town size is between twenty-five and fifty thousand, the odds of being against abortion under all circumstances, or only with the exception of rape or incest, are 1.7 times greater among people living in an area with only small towns of a thousand residents, and decline to 0.7 among people living in an area with towns averaging more than a quarter-million residents. In addition, the odds of holding prolife views in each size community are about 1.4 times greater among people living in nonmetropolitan areas than in metropolitan communities.2

Figure 8.1 Prolife sentiment by town size

In qualitative interviews, many of the people we talked to held sentiments about abortion that they were eager to express. “If a child in a mother’s womb is not safe,” a man in one small town told us, quoting Mother Teresa, “nobody is safe.” In his view, abortion is tantamount to the idea that “man can manipulate life, and decide when it begins and when it ends,” and that makes it a “grave moral crisis.” What he means is that there is corruption eating away at the moral fabric of the whole society. It is rarely the case that people in small towns personally know anyone who has actually had an abortion. But abortion goes hand in hand with perceptions about riffraff and people who are lazy and irresponsible. The idea that a woman might choose to have an abortion suggests that she is not living according to the purported standards of hard work and moral obligation that are the hallmarks of small communities.

A pattern that underscores these small-town orientations is evident in the results of another set of national surveys that have asked respondents if they think it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion under various circumstances. If the pregnancy has resulted from rape, puts the mother’s health seriously in danger, or there is a strong chance of a serious defect in the baby, upward of three Americans in four say having an abortion should be possible, and the odds of saying this are nearly as high in small nonmetropolitan towns as in larger metropolitan communities—taking account of differences in age, sex, race, region, and level of education (as shown in figure 8.2). But under other circumstances—especially ones that suggest deviations from small-town norms—the differences between attitudes in smaller and larger communities increase. If a married woman merely does not want any more children, the odds of saying an abortion should be possible are only about three-quarters as great in small towns as in larger communities. If a woman is poor and cannot afford more children, or is unmarried and does not want to marry the man she got pregnant with, the gap between small-town residents and people in larger communities is greater. And the largest gap in attitudes is toward a woman who simply wants to get an abortion for reasons of her own—the response that connotes “abortion on demand.”3

Town leaders we interviewed usually had particularly strong opinions about abortion. Those who considered it a moral abomination were likely to have spoken against it during community-wide political campaigns and at church meetings. Such admonitions could be regarded as preaching to the choir, at least in settings where there was little disagreement about abortion, and yet talking about controversial subjects on which people agree can function as a community-building practice in much the same way as backyard discussions of local weather and sports. The implied interlocutor against whom residents can vent their displeasure is Mother Nature, a rival sports team, or the strangers who are presumed to take the other side on abortion. These outsiders provide the occasion for arguments against abortion to be expressed until they are known by heart.

Consider what Mrs. Gautier, the store owner we met in chapter 3 who lives in a town of four hundred, says when asked what social and moral issues she feels strongly about. “The biggest one is the prolife issue,” she says. “If we don’t have respect for life, what is there?” Without prompting, she repeats a conversation she has had on the topic. “My daughter is a Democrat, and she says to me, ‘But you Republicans believe in capital punishment.’ And I said, ‘Yes. Capital punishment isn’t the best thing in the world, and I’m not going to say that I approve of that. But that person did something to be getting punished. That baby never had a choice. That baby never had a chance unless somebody helped it along.’ ” It is as if she is having the conversation with her daughter all over again.

Figure 8.2 Attitudes toward abortion

Mrs. Gautier has more to say on the topic, this time offering another quote from a previous conversation. “It’s like somebody said, ‘How come God didn’t send us somebody who was smart enough to figure this all out?’ And he said, ‘I did. You aborted him.’ I’m really strong on the prolife issue. And I’m sorry, but if these political parties can’t get that straight, what can they get straight? We don’t have the brains and the wonderful human intellect that we could have had. We don’t have it because we got rid of it. We destroyed it.”

These are ideas that Mrs. Gautier has herself thought about, yet it is also important to understand that they are part of the public moral discourse that ties her family and community together. At the Catholic Church she attends, the members pray regularly for the unborn. She is glad to have people there who “can talk and inform” others about the issue. The church group rejoiced with her when her sister became pregnant at age forty-seven and had a healthy baby. Mrs. Gautier likes to quote her deceased mother who had ten children. “My mother always said, ‘Well, which one of you do you think I should get rid of? Which one of you wants to be the one to be sacrificed?’ ” Aborting a baby, Mrs. Gautier insists, is like sacrificing one of your children.

Of course, opposition to abortion is by no means universal in small towns—as the evidence from national surveys suggests. The interesting question is why opposition to abortion seems to be more the prevailing ethos in small towns than a mixed view that reflects both sides of the issue. One reason is that the prolife side is in fact the majority in most towns, which means that the minority prochoice view may be less evident or less often expressed. For example, a retired farmer who lives in a town of fifteen hundred says he thinks abortion is “a decision that needs to be made by the individuals involved in consultation with doctors and spiritual advisers,” but he volunteers that “a lot of people in our community would disagree with me on that.” Another man says he is “opposed to abortion,” yet is also “opposed to the government telling me, or telling my daughter, or telling my sister if I had one that she can’t get one.” But he adds, “I can’t go out in the public forum and say what I’ve just said without running a real risk of just getting my brains beaten in as some kind of an immoral baby killer.” He keeps quiet because the prolife activists in his community are so vocal. In addition, the prochoice side frequently tends to be framed in terms that render it less amenable to public expression. This tendency is evident in the ways in which people who favor choice describe their position.

Mrs. O’Brien, the mayor we met in chapter 6, is a mother who is Catholic and has three decades of experience as a social worker in her rural community of eleven hundred. She provides a good example of someone who is strongly prochoice. “Abortion, to me, should not be in the government,” she says. “Abortion is a personal issue, strictly personal. I would like to see it stay that way. I don’t believe that it’s right of me to tell someone else their rights. I’ve got my personal feelings and I’ve given those to my children. But they are adults now and they have their own decisions to make. So for me I don’t have a strong opinion one way or the other. It’s just simply a matter of leaving it up to the individual.”

Two things stand out about the way she describes her position. One is the heavy emphasis on the word personal and related references to herself (“to me,” “I’ve,” “feelings,” “the individual”). She means that decisions about abortion are up to the individual, but also implies that how one thinks about the issue will simply be different from person to person, depending on their experiences and outlook. The other is the lack of what sociolinguists call quoted speech. Unlike Mrs. Gautier, for example, Mrs. O’Brien does not quote conversations she has had, nor does she repeat arguments she has heard others make. Indeed, her emphasis on individual choice begins as a strong assertion, yet ends with the statement that she does not have a strong opinion either way. When pressed to say more about why she holds these views, she refers to her experience as a social worker. She says she sees abortion being abused as a means of birth control and in other instances abortion being used to prevent the birth of badly braindamaged fetuses, but in none of these cases does she feel it appropriate to offer advice. “Leave it to the individual,” she says. In comparison, a person in her community who holds strong beliefs against abortion would be more likely to articulate those views as judgments that should apply authoritatively to the entire community.

Surrounded by flat, open fields of wheat, corn, and soybeans, Ellis, Kansas, is a town of two thousand situated along Interstate 70 in the western part of the state. Like most towns in the area, its population is smaller than it was in 1950, but over the past decade it has grown slightly. Although a rail stop existed as early as 1867, Ellis County was largely unsettled until the 1880s, when German Catholic immigrants from Russia arrived in large numbers. Their influence remains evident in the county’s religious composition, which is 54 percent Catholic, 22 percent mainline Protestant, and 18 percent evangelical Protestant, with the remainder adhering to several small denominations. Saint Mary’s Church on Monroe Street is by far the largest church building in town.

Abortion has long been an issue of interest among Ellis residents, as it has been statewide. In 1973, more than twelve thousand abortions were performed in Kansas. That number fell to a low of sixty-four hundred in 1987, but increased to more than ten thousand in 1991, and has remained at roughly the same level. Although Ellis County is sparsely populated, as many as ten or twelve abortions are performed among residents of the county each year. In addition, more than a hundred out-of-wedlock births are recorded annually, with up to a third of those among teenagers.

Pregnancy counseling is provided locally by the Planned Parenthood Health Center and the Mary Elizabeth Maternity Home, both located in Hays, the county seat, sixteen miles from Ellis. Besides supporting the antiabortion-oriented Mary Elizabeth Maternity Home, opponents of abortion have posted road signs throughout the county warning against abortion and have urged the elimination of federal funding for Planned Parenthood, which supports the choice to have an abortion or not.

Ellis residents have mixed opinions about abortion, ranging from believing that it is always morally wrong to saying that it should be a matter of individual choice. Some believe the issue has received too much attention, especially in view of the murder of abortion provider Dr. George Tiller in Wichita in 2009. In 2010, US senator Sam Brownback, a conservative Republican who was an outspoken opponent of abortion, ran for governor, including among his campaign promises efforts to further curb abortion in Kansas. Statewide, Brownback won 63 percent of the vote, and Democratic candidate state senator Tom Holland received 32 percent. Ellis voters gave Brownback a 72 to 24 percent victory over Holland.

One might also wonder if opposition to abortion helps in some communities to shore up their collective identity, perhaps like the witch hunts did in colonial Massachusetts. When the colony felt threatened, scholars have argued, witch hunts became a way of affirming loyalty to the colony’s basic values, especially because accusations against witches drew the community together and gave the colonists reason to declare their faith in correct religious teachings.4 A similar assertion has been made about the temperance movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when rural communities presumably promoted Prohibition as a way of protecting the traditional values residents felt were threatened by immigration and urbanization.5

Research suggests that the most vocal and best organized opposition to abortion has been in cities and suburbs where electoral clout is greatest and large meetings can be held.6 But in small towns, as we have seen in considering sentiments about moral decline, there is sometimes a sense of being besieged by an alien world, and this feeling is evident in comments about abortion as well. It surfaces especially in remarks about abortion being a problem in cities, unlike in small towns, where people presumably hold stronger values about the sanctity of life.

An example of perceived differences between cities and towns is evident in the comments of Mr. DeSoto, the man we met in chapter 5 who grew up in a community of immigrants from French Canada and now lives in a town of about eight hundred. He places great value on living in small places. He enjoyed the community in which he was raised because several generations of close relatives lived there and he could roam the neighborhood with his friends. He selected his present community not only because housing was cheap but also because the town was small. He worries, though, that small towns are beleaguered. The town he grew up in has lost population, and few of his generation have stayed. On social issues, his preference for small-town virtue influences how he explains his attitudes. He expresses his convictions about abortion not initially by stating his own view, which he says later is that abortion is “murder pure and simple,” but instead by asserting, “I don’t know why we kill babies in this country,” and then mentioning an “abortion butcher” he read about who lives in a city. The implication is that “we” who kill babies are people in cities, not residents of small towns like his. This is a theme that runs through his comments about other social issues as well, such as drunkenness and political corruption. Small towns symbolize how the world should be, and cities evoke disconcerting thoughts about where the world may be headed. Comparing the two, Mr. DeSoto states unequivocally, “People in these little towns grow up with a better set of values.”

It is one thing to imagine that small towns are a breath of moral purity in an otherwise-toxic world, but much worse to fear that town life itself is threatened. I can illustrate this point by quoting a woman in her early thirties who describes herself as a “very conservative Republican.” She is an active churchgoer who says it is important not only that people believe in God but also that they trust in the Lord Jesus Christ as their savior. She has several children and was raised as a natural-born child in a large family that included several adopted siblings. So she has multiple reasons to be opposed to abortion, the strongest of which is her faith. “Abortion is murder,” she asserts, quoting God as saying, “I knew you before I put you in your mother’s womb” and “I knew you before I put a star in the sky.” She offers an implicit reference to city life by claiming that it was sad for the nation to “cry over the four thousand people or so who died on 9/11,” yet not to mention the forty-five hundred babies murdered the same day, and the next, and the next. She also believes the larger moral malaise of which abortion is a symptom is threatening her own town. “I’ve watched small-town American women who have been in deep, dark depression over aborting their baby at age fourteen,” she says. Underscoring the point, she adds, “This is in small-town America as much as in the big city.” She feels small towns are in big trouble because they are “not sharing the way God would want us to.” Besides abortion, the other indication of rampant moral demise that worries her is sexual promiscuity. “It’s happening in small-town America as much as in big cities,” she says, noting sexual experimentation that stops short of intercourse. “We’re exchanging lower pregnancy rates for the throat cancer coming out of blow jobs that children are doing.”

This woman’s concerns about abortion are more extreme than those of many people living in small towns. In indirect ways, however, other residents draw connections between abortion and the moral rot they feel is weakening their towns. A typical example is evident in the way a man in his late forties who works as an auto mechanic in a town of twenty-five thousand discusses his concerns. The community has been growing, and as a result he has enjoyed steady employment over the past two decades, unlike mechanics he knows in small declining towns, so he has reason to feel good about his life. Although his community has become racially and ethnically diverse, he says it is foolish to mourn the past because the “good old days were never really that good.” He describes himself as a practical person who does not become interested in social issues unless something practical can be done about them. Yet he is adamantly opposed to abortion even in cases of rape and incest. The only exception, he says, would be if a pregnancy truly endangered a woman’s life. The reason he is so strongly against abortion is not only that it is, in his view, taking the life of an innocent baby but also because it indicates the more pervasive decline of family values in United States and even in his own community. “Life has gotten so busy,” he says, “that people don’t have the time to sit down together like they used to. The family isn’t as close as it used to be.” He thinks the family used to be the source of “strength and nurturing and love,” but “we’re getting away from that.” He comments, “This town has struggled for a long time with finding family-friendly things to do.” But the community’s efforts have had only mixed results. It isn’t that he is thoroughly depressed by the direction things are headed. He just worries about his children’s future and doubts that any practical solutions can be found.

The sense of near futility evident in this man’s remarks is a key to understanding both the activism and lack of activism in small towns toward abortion. Activists feel that abortion is a particularly heinous evil that they can do something about. For example, the basketball coach I mentioned earlier is proud that some of his students join an annual bus trip to the nation’s capital to protest the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade. Overturning the decision would be an important victory that he and his students feel they can help bring about. In contrast, most of the people we talked to said they were against abortion, and personally would not have one, or want their wife or daughter to have one, and yet they expressed reservations about the more aggressive prolife activism they had heard about. As one woman observes, “When you have an unwanted pregnancy, none of your options are good”—which means abortion may be wrong, but she dislikes activists turning it into a hot-button issue. She thinks activists’ play on people’s concerns “because it is not something that affects most people personally. They can think this is a big deal, and I don’t do it, so that makes me feel better about myself, but if someone else does it, they are a terrible person.”

This woman’s perspective stops short of supporting activism because it identifies implicit or even intentional manipulation of people’s concerns by activist leaders. Then there is the view that abortion is morally wrong, and yet not an issue that should become a matter of judgment or criticism among good friends and neighbors. A live-and-let-live attitude of this kind leaves the door open for differences of opinion while retaining faith in one’s own convictions. “I am antiabortion,” a Presbyterian woman in a rural town of a thousand says, adding, “I personally can’t take exception with the person who makes that decision.” She is “not fanatically against abortion” like some of the groups she regards as staunch prolife activists. She just feels that abortion is not good for the country.

Not surprisingly, there are also people in small towns who resist prolife activism, even though they are basically opposed to abortion, because small-town culture itself exposes them to several crosscutting currents of thought. A good example is a woman in a town of fifteen hundred who attends a conservative charismatic church. She believes abortion is fundamentally wrong, and finds support for this conviction in the teachings of her church as well as from most of the people she knows at church and in her community. She is conflicted, though, because she does not feel the government should be “telling someone about a personal decision like that.” This skepticism toward government intrusion is also a strong motif in the culture of her community. In addition, she thinks of herself as a feminist—an identity she regards as a distinguishing feature of her generation. “I think my generation really did help to wake up women to take charge and to respect their bodies,” she says. “Rape is not the victim’s fault,” she asserts, implying that understanding this fact has to be part of any discussion of abortion. Ultimately, she holds firmly to her view that abortion is wrong, but wishes that the debate, which she regards as unfortunately explosive, could be more nuanced.

The conclusion to be drawn from instances like these is that opinions about abortion vary considerably even in small towns that otherwise might seem to be remarkably homogeneous. Although outspoken support for prochoice policies is rare, the prolife position is far more complicated than news stories and surveys usually suggest. Nor is it satisfactory to conclude that the public in small towns is simply part of the muddled majority. The reason opinions may seem muddled is that observers have not stopped to pay sufficient attention to the multiple factors shaping opinions. In our interviews, the most important of these factors include the basic and widely shared conviction that human life is precious and that taking a life in the womb is wrong, the perception that fellow townspeople generally share and support this conviction, an us versus them mentality that often perceives small town virtue over and against as well as indeed threatened by big city and mainstream media disrespect for basic values, misgivings about government intervention into personal life, doubts about extremist antiabortion activism, an emphasis on personal decisions that not only argues for individual responsibility in sexual behavior but also acknowledges the right of people to form their own opinions, and awareness of crosscutting social influences that may include gender and age cohorts as well as church and town, or even more personal experiences such as having been adopted or having had a baby out of wedlock.

How people sort out these complex influences cannot be understood by suggesting that people have a cultural tool kit that pretty much lets them do whatever they deem to be in their self-interest amid a world so fragmented that values hardly matter. That throw-up-your hands approach runs counter to what people actually say and believe about their deep convictions, and fails to illuminate the influences that town life and other social factors have in shaping attitudes. It especially falters in shedding light on the behavior that results. Weighing complex considerations about abortion encourages people to take a pragmatic approach toward dealing with it. While it is true that many people do not think enough about this particular issue for it to matter much one way or the other, those we talked to who do care about it are seldom engaged in activist movements. Getting involved to that extent requires a rare combination of interpretative frameworks, such as believing so strongly that abortion is always wrong and feeling so threatened by alien values that government intervention seems essential, and is as much attributable to social network connections, as studies have shown, as to convictions.7 The more likely response is to take action that is deemed helpful, and at the same time does not bring in government too directly or violate principles of individual freedom. Concretely, the action that best fits these considerations includes voluntary contributions of money or time to support crisis pregnancy clinics. Townspeople we talked to saw that as a pragmatic solution. It provided counseling, information about adoption, and in some instances community support for mothers who decided to keep their babies. Crisis pregnancy clinics also served as vehicles for antiabortion activists to heap guilt on expectant mothers for considering abortion, but that was not how most supporters of these clinics in small towns understood their purpose.

The pragmatic approach toward reducing abortions fits well with smalltown residents’ emphasis on common sense and ingenuity. It seems practical to do a little that helps one woman through a crisis pregnancy, rather than expending a great deal of energy on movement activism that may or may not accomplish anything. A critic might argue that saying something like “we need to help mothers have their babies” is an after-the-fact justification for doing little, but in reality it is a statement that also motivates action, such as contributing money or time to helping at a crisis pregnancy clinic.

HOMOSEXUALITY

In national surveys, conservative attitudes toward abortion usually go together with negative views toward homosexuality. And in reality, many of the states with constitutional bans on same-sex marriage—such as Alabama, Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska, and North Dakota—are ones that have large numbers of small towns and have also sought to restrict access to abortion providers. Thus, it is not surprising that the data summarized in figure 8.3 shows support for a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage, were one to be proposed in the US Congress, among respondents in a large national survey, with comparisons among those living in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties in which the median population of towns ranged from less than a thousand to more than a quarter million, and with differences in gender, race, education, age, and region taken into account.8

Figure 8.3 Support for antigay amendment

Most of the variation in the figure, however, occurs at the lowest and highest values of town size—meaning that among most towns in between it matters relatively little on this particular issue whether the respondents live in an area comprised of smaller or larger towns. There also appears to be a wider range of opinion about homosexuality than there does about abortion, even in small towns, and on some survey questions the responses given by people in small rural communities are indistinguishable from those of metropolitan residents when factors such as age, region, and level of education are taken into account.9 In some ways, this is surprising because small towns are often regarded as places where gossip and peer pressure discourage nonconformity, and where images of rural masculinity promote homophobia.10 Unlike in large cities, small-town residents whose sexual orientations differ from those of the majority may find it more difficult to escape attention. Yet when asked if they personally know someone who is gay, close to 90 percent of people living in small nonmetropolitan areas say they do, and about half of these say the person they know is a member of their family or a close friend.11 As a consequence, an emerging attitude in small towns appears to hold that homosexuality can be tolerated as long as it stops short of disrupting the local community—or leads to behavior like that “bunch of idiots in California.” Among heterosexual residents who consider themselves relatively well informed and tolerant, this view expresses itself in support for gay rights, but usually does not condone gay marriage. Residents say they personally know someone who is gay or have a gay person in their extended family, and believe that gay people should be permitted to teach, join churches, and hold public office the same as anyone else. Just don’t flaunt it, is the caveat. The more conservative stance holds that homosexuality is a sin and that gay people should not enjoy the same rights as everyone else. The reasoning is usually that some damage to the community will follow if rights are extended. Heterosexual families will somehow lose control over their children’s morals and worse things may follow, such as child abuse, pornography, and sexual addiction.

Mrs. Saunders is one of the people whose views toward homosexuality fall toward the more tolerant end of the spectrum. She says that she has a gay acquaintance, although he doesn’t live in her town, and has no problem being his friend. Nevertheless, she insists that she does not want homosexuality to be “in front of me”—meaning that it should stay out of the public eye. “As long as they’re respectful and not trying to advertise it,” she says, “I don’t mind. It’s your deal.” She even believes homosexuals should be allowed to marry. Her reasoning is that marriage is pretty much a private matter and that what counts should be a person’s happiness. “If it’s going to make them happy,” she remarks, “who cares. I don’t see it as a problem. They’re not hurting anyone.” She underscores the same principle in arguing that homosexuals should not be denied membership in churches. Even though that would probably have a public aspect to it, she thinks the psychological harm from exclusion would outweigh the possibility of any damage to the collective good of the congregation. “God has the right to judge,” she says. “We don’t.”

Mrs. Barnes, the woman we met in chapter 5 who works at the bank in a town of seventeen hundred, expresses a contrasting—but generally tolerant—perspective. She is a lifelong Catholic who regards herself as a conservative Christian. She is adamantly against abortion and generally votes Republican for that reason. But she is not as opposed to homosexuality as one might imagine. Although she opposes gay marriage, she believes gay people should in other ways enjoy the same rights as anyone else. “I have not been around it a whole lot,” she acknowledges. Most of what she knows about it is what she has seen on television. She says it is important to respect how people lead their lives. “Years ago, I don’t think that the average person in a small town would have accepted it,” she says. “But I think it is becoming more acceptable.” She does not think there are many gay people in her town, but she knows it is more common in some cities. She has personally known people who were gay, she notes, and that has affected her views more than anything else. “You just can’t be a person who says I will not accept your way of life.”

One of the reasons Mrs. Barnes emphasizes respect and acceptance is that she feels her church has been relatively silent about homosexuality, unlike its aggressive condemnation of abortion. Although she assumes the Vatican is against homosexuality, she has heard few denunciations of it in her parish. That view is one we heard from other Catholics as well. As one remarked, the church is not trying to “fix homosexuals,” and in the absence of that, she figures “that’s just how a person is, that’s how God made them.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum are townspeople who definitely believe that homosexuality is morally wrong. Among residents who hold this view, some do try to apply the same norms of small-town civility to homosexuals as they do to heterosexuals. For example, a Presbyterian woman who regards homosexuality as a violation of God’s law says she wants to avoid being hateful and “come to a good place” in her thinking on the topic. “I’m not there yet,” she admits, but “I’m working on it.” A Lutheran woman in her community struggles as well. She says her church is quite conservative on the issue, but people are reluctant to say much about it for fear that someone’s son or daughter might be gay. She is relieved that her church does not condone the ordination of gays and lesbians because there would be a ruckus if it did. Other townspeople are less charitable. They are convinced that homosexuality is condemned in the Bible and, equally troubling, represents a worrisome cultural shift in the wider society. These concerns are evident in comments such as “they’re so pushy it makes me sick,” “you see a lot of this in big cities,” “the [gays] are really trying to take over,” “television seems to glorify them, and I’m really sick of that,” and “they are being treated like saints because of their sexual preference.”

With opinion divided about homosexuality, a number of states with large rural populations have passed constitutional amendments banning gay marriage, and as we saw in the last chapter, congregations have felt strongly enough about the issue to split or withdraw from their denominations.12 One reason for these events is that statewide referenda and congregational policies represent public goods—laws and decisions that affect everyone, or seem to, whether people are gay or straight—and thus force residents to take sides. A related reason is that the opinions of those who oppose gay rights and same-sex unions are often articulated more forcefully than the views of people on the other side. As is true of arguments about abortion, townspeople with moderate or liberal perspectives about homosexuality feel they are in the minority in their communities, feel uncomfortable speaking out, and believe the issue is private enough that it should not become a matter of public discussion or policy.

How a live-and-let-live attitude of this kind works itself out is evident in the remarks of a pastor who regards himself as open minded and tolerant, and yet is unwilling to take a strong stance in favor of gay ordination or same-sex unions. “I do not have any great zeal about same-gender relationships,” he says, “except that I think the making and keeping of commitments is important.” For him, honesty and fidelity are critical enough that he emphasizes them rather than becoming an activist on either side of issues about homosexuality. Ms. Clarke makes a similar observation. “I think it’s important to commit to something or to someone,” she says. “If your choice is to commit to someone of the same sex, I don’t really have a big problem with that.” In her case, she also believes that being this open minded is “pretty darn rare” among people with rural backgrounds similar to hers. Her comment suggests that she probably would not say much about her views among the people she works with in her community.

The fact that residents of small towns who consider themselves moderates or liberals on homosexuality are reluctant to talk publicly about it does not mean that they haven’t been thinking about the topic. Especially if they belong to congregations or live in states where gay marriage has been discussed in the media, they probably have heard views they liked or disliked. But their opinions are guided by a mixture of rational arguments, emotions, personal experience, and views about what is good for their community. How these complex considerations come together is clearly illustrated in the comments of a man in his sixties who lives in a town where churches and government officials have discussed homosexuality on a number of occasions. He is rather tired of thinking about the issue, and his exhaustion stems as much from mixed sentiments as anything else. He became convinced several years ago that the idea of homosexuality being a choice was not a defensible argument. He just thinks, “When did you choose? Do you remember when you made that choice? Do you remember standing in the school yard, and there’s the quarterback and there’s the head cheerleader, and you decided which one had the cutest fanny?” He thinks people do not choose but instead are born with one sexual orientation or the other. And yet his emotions are not in the same place as his rational arguments. “I’m not ready to be sitting in church and see Bob put his arm around Frank,” he says. “I’m not going to bash them, but I’m not ready for that either.”

For most of the people we talked to, homosexuality was a topic they knew was generating new understandings that were either leaving them upset or feeling that they would eventually have to adopt new attitudes themselves. A man in his fifties who lives with his wife in a tiny rural community, for example, says homosexuality is something nobody would have been aware of in his area twenty or thirty years ago, but now it is just one of those changes everyone is getting used to. “I guess if that’s what you want and you’re not bothering me, I can live with it,” he says, mentioning two gay couples in the area. “They don’t seem to bother nobody. Everybody kind of knows what’s going on.” This man attends a conservative Baptist church that does not condone homosexuality, and yet his strong sense that everyone should be free to be themselves is more influential than the church in shaping his thinking. As for homosexuals marrying, he says, “I guess you ought to have the right to choose that way of life if that’s what you really want.” Others made similar comments, noting friends they knew in high school who are now known to be gay or saying that their children have challenged them to think more deeply about the issue.

SCHOOL CONTROVERSIES

Small towns and rural communities have been the location of some of the most contentious battles in recent years over school curricula. The widely discussed 2005 Kitzmiller case in which a judge ruled against teaching intelligent design as part of high school biology lessons, for example, occurred in Dover, Pennsylvania, a town of fewer than two thousand people.13 Controversies about evolution have been played out in states with large rural populations, such as Alabama, Kansas, and Louisiana, while questions about teaching the Ten Commandments or having them displayed in public buildings have taken place in small communities, such as Maumelle, Arkansas, and Stigler, Oklahoma. Polls show that the US public at large is divided over these issues, but residents of small nonmetropolitan towns are generally more favorably disposed than people in larger communities toward prayers, Bible reading, and lessons about creation or intelligent design in their schools. Indeed, one survey suggests that an avid small-town proponent of evolution would likely be outnumbered nearly ten to one by fervent creationists.14

The notion that small towns are filled with people who want Christian dogma promulgated in public classrooms, though, is false. While it is the case that small homogeneous communities find it easier to encourage prayer, Bible reading, and creationism in schools than cities with religiously diverse populations do, it is rare for townspeople to argue that public school curricula should include explicit religious teachings. Residents have read or heard too much about church–state controversies to be in favor of that. Instead they contend that the Ten Commandments, for instance are universal moral teachings that will have a salutary effect on the community and need not be taught as biblical doctrine.

As immigration brings greater ethnic and religious diversity to small towns, it is certainly conceivable that some communities will react by arguing all the more forcefully that traditions such as school prayer or teaching the Ten Commandments in school should be preserved. For example, one of the pastors we interviewed in a town of eight hundred that was beginning to feel the effects of immigration asserted in no uncertain terms that the Ten Commandments should be posted in public schools and taught as regular parts of the curriculum. “The words ‘separation of church and state’ are not in the Bill of Rights or the Constitution,” he said in defense of his view. Or as a church member in another community complained, “We [Americans] exaggerate the Jewish holidays, Buddhism, and of course Islam, but are not allowed to teach the Christian viewpoint.” Yet it seems more likely that communities wanting to preserve moral traditions will find other ways in which to do so. The pastor of a conservative evangelical church in a town with several recent immigrant Hindu families, for example, says he would not want his children learning Hinduism in school if they were living in India, so he figures it best to preserve his community’s spiritual traditions through the efforts of his church. In other interviews, people draw sharp distinctions between religion and morality.

Consider the position articulated by a woman who says it would be difficult to teach the Ten Commandments as religious doctrine in her community’s school. “We have Islamic kids, we have Jehovah’s Witnesses, we have Jewish families,” she says, so despite the fact that she would like the Ten Commandments to be taught, she feels they should be distilled into moral principles and not taught as religion. She happens to live in a city where the population is in fact quite diverse. But a woman in a small town who understands that even Protestants and Catholics may have different views offers almost the same reasoning. “Even if you don’t believe in the God that I believe in,” she says, “a logical person could agree that it would be wrong to put something first in life that is not God.” And if people could agree in principle on the first commandment, she believes they could probably see the value of other commandments as moral ideals.15

Lars Johansen is a fifty-year-old newspaper editor—a Lutheran whose wife is Catholic—who has raised six children in a small town. It is interesting to contrast his views about the Ten Commandments and prayer in public schools with the woman I just quoted. While she illustrates the fairly common view that some basic underlying truth can be found in the Ten Commandments that would elicit agreement from almost everyone, Mr. Johansen considers it more prudent to recognize the differences among religious traditions. Some of the Protestants in his community, he says, think Catholicism is evil. If those Protestants wanted the Ten Commandments taught in public schools, they might also have to tolerate prayers to the Virgin Mary. “I believe in the wisdom of the Constitution,” he says. He thinks the people who are trying to force their own religion down other people’s throats had better think twice. “You allow the camel’s nose under the tent,” he explains, “and you get the other end too.”

The orientation toward such curricular controversies that seems to outweigh strong ideological positions is the same small-town pragmatism that we have seen in previous chapters. This view is evident when townspeople say they would like to see the Ten Commandments taught or prayer allowed back in the schools, but figure there are better ways of “skinning a cat,” as one man put it, such as encouraging parents to do a better job of instructing their youngsters, or having the schools teach honesty, fidelity, and generosity as moral principles. Although there have been activists on both sides, this is also the stance most evident at the grass roots about the teaching of evolution.16

Without a doubt, there are residents in small towns who feel strongly that evolution should not be taught at all, or if it is, should be exposed as false doctrine. This view is well represented by the woman I mentioned earlier who talks about the danger of children getting cancer from giving blow jobs. Although her thoughts on that issue are unusual, to say the least, she is not the type who spews right-wing invectives on talk radio. She is a college graduate who held a position as a banking executive before focusing full-time on raising her children. She says she was taught evolution in sixth grade and made up her mind at that point that the idea was nonsense. For a long time she had no cause to think further about it, but now that her children are in school, she has been revisiting the topic. She has found a number of reasons to believe that evolution is not just scientifically wrong but also damaging to human society. One reason, she says, is that the theory of evolution was responsible for slavery. People were taught that “the black man hadn’t evolved like the white man,” she says, “so was inferior. That’s how slavery came about.” A second reason is that according to evolution, death would have happened before sin, but that contradicts the biblical view of sin being the cause of death. A third reason is that the big bang theory, as she understands it, suggests that everything is spun off clockwise from a single dot, and yet there are planets going counterclockwise in the solar system. A fourth problem, she says, is that an evolutionist would have to believe that the moon used to be part of the earth, which she believes could not have been the case. And a fifth reason evolution is wrong, she thinks, is that the biblical story of the flood explains the Grand Canyon better than eons of evolution. Above all, she thinks it is demeaning to imagine that a human could have ever been a monkey.

A knowledgeable scientist would find these assertions ludicrous. They are extreme even among the fiercest opponents of evolution, but they do illustrate something important about the relationship between living in a small town and holding radically conservative positions on social issues. This woman did not believe in these arguments because she had heard them articulated in her town. Even though she lived in a predominantly Republican community and went to a conservative church, she had never expressed her views about evolution publicly because she figured they would not have been shared. Instead, she quietly read on her own—and consulted Web sites on the Internet—to find support for the conclusions that she had arrived at in sixth grade. She was more atypical than typical of the way opinions are formed and discussed in small towns.

The more common approach in small towns—and probably in larger communities as well—is to search for practical ways to reconcile science and faith. The solutions that people come up with are nearly as varied as the people describing them. For example, a man whose wife teaches science in their small community’s high school portrays her as the “believer” in the family and himself as the guy who wants facts, so as a couple they mostly have an ongoing debate about evolution and creation. A woman who learned science in high school says the matter is pretty simply resolved as long as you remember that science tells us how and religion tells us why. She interprets the distinction to mean that evolution should be taught in school and creation should be promoted in church. Another woman gives a fairly typical answer when she says she is just confused and hopes someday to get it all sorted out. Yet another resident asserts that the Bible depicts God as a progressive deity whose relationship with humanity changes, which leads her to believe that evolution is simply God’s way of doing things.

But whether they feel confused or have it all figured out, few of the people we interviewed felt it was necessary for school boards to keep going back and forth in efforts to revise science curricula. When required to choose, these townspeople say they would vote for a school board candidate who is critical of evolution or a different one who is not, but they mostly want the issue to go away. “Nobody is going to win the argument,” one man laments, telling how creationists in his state brought in a big gun who had a gift of gab and the other side mustered the support of top scientists. “Just back and forth, it’s never ending,” echoes a fellow resident. Or as another man says, noting that his wife is a staunch believer in evolution and he still prefers the creationist view, “I won’t stand on a fence post and preach it or anything,” adding that the best way to approach the topic in schools is “carefully.”

The reason they want the issue to go away is not that they consider it unimportant but rather because they figure the obvious solution is to be open minded—or as one woman says about evolution, “You learn it like anything else in science. You learn it for what it is and go on.” For some, like one of the men we interviewed who described himself as a “literal six-day creationist,” it made sense that evolution should be taught in the interest of knowing all perspectives, and for others, it seemed like a good idea for students to know about intelligent design in case there were holes in scientists’ evidence for evolution.17 As one of the science teachers we interviewed put it, “I’ve tried to maintain a fair balance in my classroom. In education we’re not there to preach to people. We’re there to get them to think. I’m not one of those who say everything is black and white.”18

AN ETHOS OF COMMON SENSE

There are other moral issues that townspeople said were important enough that they should receive more attention than they do—problems such as drug use and alcoholism, job training, school improvement and consolidation, the gap between rich and poor, and protection of the environment. But the most contentious issues—abortion, homosexuality, and teaching the Ten Commandments and creationism—were ones that residents of small towns portrayed quite differently than an outside observer might have guessed from watching stories on Fox News or CNN.

Whole communities were sometimes divided between factions that supported or opposed a revision to the school curriculum, or because a local pastor declared themselves to be in favor of gay marriage. Had they known such fights were brewing, cable news producers would have sent reporters to record the most incendiary statements from both sides. Having watched these segments, viewers would have missed understanding what was truly the case in most small communities.

Polls are useful reminders that sentiments on such issues as abortion, homosexuality, and evolution are usually more conservative in small non-metropolitan towns than in larger metropolitan communities. At the same time, polls must be interpreted clearly if they are to be taken seriously at all. When aggregated nationally, surveys show that residents of small towns register opinions that are mixed, nuanced, and heavily dependent on how questions are asked. Aggregation also fails to adequately reflect the fact that sentiments in one community may be quite different from those in another one.

Townspeople are good observers of the processes that shape the discussion of contentious issues in their communities. The fact that interviewees share ideas that span the ideological spectrum and, in interviewees’ own view, deviate from local norms is an indication of the candor with which they describe their opinions. What comes through repeatedly is the fact that discussions of controversial issues take into account residents’ expectations of how others with whom they associate may react. People refrain from expressing their views about abortion or homosexuality for fear of offending a neighbor or fellow church member, and they withhold commentary even when they may have strong opinions because they feel the issue is complicated, confusing, or requires tolerance and respect. It is not uncommon for statements of absolute moral conviction to be couched in personal language (“my personal persuasion,” as one man puts it)—not because people are moral relativists or because their opinions are private, but instead because they reflect community norms of getting along and respecting differences. What people want to believe is that their communities are fair minded—places where “we can live and get along, disagree, yes, but not try to force others to accept our views.”19 In this regard, inhabitants of small towns are like other Americans who generally abide by norms of civility, but are probably more attuned to these norms because so much of small-town life is public and is communicated both in direct interaction and in behind-the-scenes conversations among neighbors and friends.

The extent to which discussions of moral issues are implicitly monitored by community norms is, I have suggested, an important consideration in understanding why conservative opinions seem to predominate as often as they do despite the fact that sentiments actually are divided and nuanced. The few who may be most agitated about abortion, gay marriage, or some other issue are more likely to speak out as well as frame their arguments as absolutes. When one side implicitly appears to be in the majority, residents whose views are in the minority are less likely to state their opinions publicly. This is why church votes about gay ordination or local school board elections sometimes produce surprises. What was popularly assumed to be the majority view, turns out not to be when secret ballots are counted.

Above all, interviewees in small towns seem intent on demonstrating that a commonsense, pragmatic, open-minded orientation to contentious issues prevails in their communities. It is they who are the guardians of this spirit, which they believe to be profoundly American and indeed responsible for much of the good that has been accomplished since the nation’s founding. A can-do attitude that also respects common decency, considers both sides of a controversial issue, and finds a way forward is one that small-town residents believe is fundamentally transmitted in strong two-parent families along with schools and churches, and is maintained from day to day and year to year by other-regarding neighborliness as well as community involvement. Residents worry that the same traditions are not being upheld in cities and fear that their communities may be threatened by corrosive tendencies in the wider culture. These concerns help to reinforce the conviction that living in a small community is a good choice. And at the end of the day, reactions to perceived threats are less critical than the belief that open-mindedness and fair dealings will prevail.