CHAPTER SIX

Visualization

The association techniques discussed in the previous chapter are largely verbal, involving the use of similar-sounding words or phrases, or words that evoke a specific emotional or intellectual reaction. In this chapter, you will learn about ways to use mental images to link new memories with old ones to bring more meaning to the new memories.

You have already tried out this memory improvement technique by creating the story about the shopping list. In that example, you learned to tie the list to a series of vivid images that had specific associations for you. It probably will not come as a surprise that association and visualization are closely related—in fact, it’s tough to use one without the other. The words you use to associate one memory with another one bring images to mind immediately, making the memory that much more vibrant.

Choosing a vivid visual image as well as a word or phrase engages a second sense, allowing you to use more than one of your senses to remember the new information. Not only do you hear the memory verbally, but you can see the connected image as well. The more senses you can employ, the more parts of your brain will be engaged with that memory. This strengthens the new information and gives it more significance—more value—to your brain, creating additional pathways across synapses to help you recall the memory more easily.

Use Your Imagination

The concept is fairly simple: Think of a visual image that will remind you of the thing you want to remember. Link the image with the memory, making both the image and the new information come to mind at the same time.

To make visualization work as a memory trigger, however, you need to make that image as interesting and memorable as possible. Remember the list of characteristics at the end of Chapter Four—the kinds of information that are easiest for your brain to remember. If you can make your visualization funny, sexy, personal, distinct in its location, surprising, or physically unusual, you have a much better chance of remembering it than if you use something nondescript, abstract, and boring.

Let’s say you want to remember the names of the early spring flowers in your garden: tulip, daffodil, and hyacinth. Just looking at the flowers may not bring the names back from memory, because you have not linked the flower names, the way the blooms look, and a vivid image in your mind.

Look at the tulip—it looks like a cup. Imagine bringing a cup of your favorite tea to your two lips. Now you’ve made a play on words—”two lips”—from the name, and a vivid image of this beautiful cup filled with tea. Perhaps you can link this with another image: you and a female friend having tea in the living room of her house. This image adds emotional value to the memory, creating the additional linkage to another part of your brain and strengthening your recall.

The same happens with the daffodil: The name sounds like Daffy Duck, and you can imagine the trumpet-shaped part in the middle of the flower to be a big, yellow Daffy Duck bill. Every time you see that duck bill coming at you, you’ll know it’s a “Daffy-dil.”

The hyacinth has a completely different shape—it’s a cluster of tiny flowers along a stalk. Its scent is so rich and sweet that it’s almost sinful to inhale it—so you quickly link the high-a-sinth to the idea of intoxication (being high), which may bring all kinds of memories to your mind. Or you might think of the medication hyoscine to equate it to being drugged. For the purpose of this example, imagine a bottle of a sweet liquor, like honey bourbon. You might even take this a step further, looking at the shape of the hyacinth stalk and equating its phallic shape with a penis. Now you have more than one kind of “sin” linked to this flower, and it’s unlikely that you will ever forget its name. You’ve also incorporated your sense of smell, and perhaps even the sense of taste in regards to the liquor.

Once you have these three images, build a mental relationship between them. Take the first visual you thought of: a cup of tea. How can you create a connection between this and Daffy Duck? Imagine Daffy Duck sipping your cup of tea from the tulip cup. Now add the third element: a bottle of honey bourbon. You can see Daffy pulling off one of his signature pratfalls, upsetting the bottle, and letting it pour into his cup. It doesn’t matter how silly, obscene, violent, or bizarre the image is, as long as you make it memorable enough to stay in your mind.

You can link your visualizations in all kinds of ways: merging them, having one ride on top of the other, covering one with another, wrapping them around each other, smashing one with the other, or having a character or person use the other items in the image. As you get better at creating mental images quickly, you may be surprised at the number of elements you can crowd into a visualization to make it memorable—allowing you to remember long lists of information for as long as you need to.

The Peg List/Number Rhyme Technique

In the example about the flower names, we used a freestyle approach to demonstrate the power of visualization. Using this technique, you can come up with images from many different areas of your life, relating them to the sound of the flower’s name and the appearance of the flower.

Visualization can blend with other kinds of mnemonic devices that offer an initial structure from which you can supercharge your imagery. Let’s begin with a time-honored memory booster known as the number rhyme technique. This provides a very effective way to remember short lists of items.

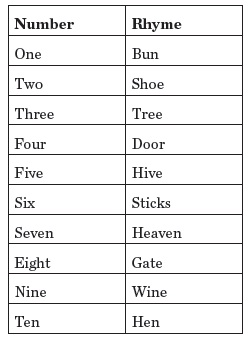

Begin with the numbers 1 through 10. Match each number with a word that rhymes with it. Here is the list of the rhymes used by AdLit.org, which provides resources for learning and memory to parents and educators of kids in grades four through twelve:

This list is called the peg list, the standard list of words that are pegged permanently to the numbers. You can replace any of these words with rhymes that are more meaningful to you, but make sure that the words you choose rhyme with the numbers. This creates both a visual and an auditory connection between the words and numbers, strengthening these links in your brain. It also makes the words and their corresponding numbers easy to memorize.

It’s also important that each word represent an object, something that provides you with a visual image. For example, if you decided to use “done” instead of “bun” to rhyme with the number one, what kind of visual image might “done” evoke? It could be different in every season, or from one day to the next. To make this memory method work properly, the word you choose needs to bring up a standardized image instantly. You will always know what a bun is, and if you imagine a hamburger bun on one day and a glaze-covered sticky bun on another, it’s still a bun.

The number rhyming method is particularly useful for memorizing a list that has to be recalled in a specific order. For example, let’s memorize the five steps of the scientific method, in the order in which they must take place.

- Research

- Problem

- Hypothesis

- Experimentation

- Conclusion

How can the peg list help you remember these steps? Use the peg words to create a visual image for each number, and then link that image with the item corresponding to that number.

- Research: A scientist in a white lab coat munches on a cinnamon bun as she reads through a big stack of dusty books.

- Problem: The scientist walks down the street and suddenly develops a problem and falls, because she’s lost the heel of her shoe.

- Hypothesis: The scientist sits under an apple tree until an apple falls and hits her on the head, just like Isaac Newton. This is how Newton formed his hypothesis about the rate at which objects fall.

- Experimentation: The door to the scientist’s lab swings open and you can see the scientist pouring smoldering liquids from one test tube into another as she performs her experiment.

- Conclusion: Bees rush from a hive and buzz around the head of the scientist as she busily completes her calculations and has an “aha” moment, coming to her conclusion.

Read these through two or three times and visualize each of these scenes in as much detail as you can; then put down this book and see if you can remember the five steps of the scientific method. The visuals are silly but just logical enough to make for memorable tools that will help you recall the steps. You can make your own images as crazy as you like, as long as it will help you remember them.

Once you’ve made your peg list, commit it to memory so that you can reference it instantly any time you need to recall a list of items in a specific order.

The memory experts who win major competitions create peg lists that stretch way beyond ten numbers, often going well into the thousands. If you frequently have more than ten items to remember, you can lengthen your peg lists with all kinds of keywords: shapes, famous people, kitchen items, foods, things you use in a hobby, the names of the planets, tree and flower species, animals, and other nouns that provide short, simple, easily remembered images. You will need to memorize your peg words so you can recall them instantly, and the experts recommend using basic learning tools like flashcards to quiz yourself until these words and images become second nature to you.

Chaining and Story

Now that you understand how to link peg list images with the items you need to remember, you’re ready to take the next step. A technique called chaining helps you recall all of the items in a list, or a list of items in a specific order, using each item as the trigger for the next one.

Let’s take the names of the seven dwarves in the Disney animated film version of Snow White—one of the bits of trivia that tends to pop up at parties, resulting in hilarity as people try to remember all seven. Chaining allows you to link these names in a way that gives each of them lasting meaning:

- Doc tries to treat Sneezy for his chronic sinusitis.

- Sneezy leaves Doc and goes into the bedroom to lie down. He sneezes hard, waking up Sleepy.

- Sleepy gets up, stumbles around in a sleepy haze, and knocks into Grumpy, spilling Grumpy’s soup.

- Grumpy gets mad and hollers at the first person he sees—who happens to be Bashful, who is too shy to complain or put up a fight.

- Bashful edges behind Dopey, using him as a shield.

- Dopey doesn’t get it, and runs off to go into town with Happy.

- Happy is pleased to have the company, and lives happily ever after.

With all of the dwarves doing something characteristic of their names, it’s easier to remember them than it was before you set up this chain of events involving all of them. You can embellish this kind of chain with all the details you want, adding humor and vivid imagery, and making the chain even more memorable.

This chain quickly takes on the timbre of a story, but the seven dwarves already have a whole fairy tale of their own, so putting them in a new story may become confusing. If this is the case, you can use their names to create an entirely different story that will make the names memorable. Here’s a simple one:

I felt Sleepy when I got up in the morning because I went to bed too late, which left me feeling Dopey all day. By evening, when I started to get Sneezy, I knew I had a cold. I was not Happy. I thought I’d better call the Doc, but I’m really Bashful about such things, so I just got Grumpy and hung out at home.

Now, let’s embellish this story with details that make it more memorable:

When Julie called Rachel around noon, she had a lot to tell her. “Was that some party last night, or what?” she asked. “I was so Sleepy this morning because I didn’t get to bed until, like, four in the morning. No wonder I feel so Dopey today—or was that because of those brownies? Anyway, I shouldn’t have drunk out of other people’s cups, because now I’m Sneezy, and I know I’ve got a cold. I can’t go to the Doc, because I’m really Bashful about needles. Want to come over? I don’t know if I’ll be Happy or Grumpy, but we can watch a video.”

Of course, your story will be different, with imagery that’s more meaningful to you.

Chaining and stories rarely are used separately, as one naturally flows into the other. They make it easy for you to remember a list of items because they provide a context, while making each of the points you must remember an integral part of a larger tale. If your story does not lead to immediate recall, take a closer look at it—maybe you need to ratchet up the details to make it more memorable. Adding something a little naughty, funny, sexy, violent, or even illegal (hence the brownies, unless you’re in Colorado or Washington) can make the story more vivid and turn average details into great mental hooks.