CHAPTER SEVEN

Chunking

Why are telephone numbers divided into three groups: the area code, exchange (the first three numbers in a local telephone number), and subscriber number?

Aside from the practical concerns of sending the call to the correct phone, telephone numbers adhere to two different premises proposed by George Miller, the father of “the magic number seven,” as discussed in Chapters One and Four. Miller determined that people can remember seven bits of information, plus or minus two, so local telephone numbers are seven digits long. The research didn’t end there, however: Miller also discovered that people can remember seven chunks of information—groupings of words, numbers, facts, or other data—that bring together individual elements to form a new whole.

While remembering ten digits of a phone number would be daunting for many people, remembering the elements of three groups of numbers turns out to be a great deal easier. You know your own area code by heart, so even if you are required to dial it in your calling area, you don’t have to think about what it is. Likewise with the exchange. It may be the same throughout an entire small town, suburb, or calling area, so you can recall it fairly easily even if your area has a number of different exchanges. So it’s only the subscriber number—the last four digits of the phone number—that may give you trouble. Given that it’s just four digits, however, it should be a snap to memorize by saying it aloud a few times.

Simplifying the use of an entire worldwide utility by dividing its identifiers into chunks may be one of the most impressive industrial uses of psychological research ever executed. If the entire world can remember phone numbers by dividing them into three chunks, then you certainly can master the memory encoding method called chunking, in which you will do the same.

From Random to Meaningful

Chunking takes bits of information that seem random, like lists of words or numbers, and groups them together to create a more meaningful arrangement. The telecommunications industry not only mastered this, but it took the concept a step further by creating vanity phone numbers, the ones that spell out words. For example, you may not immediately associate the telephone number 800-356-9377 with a gift delivery service, but when you discover that the number spells out 800-FLOWERS, you’ll make it your top-of-mind, go-to service every Mother’s Day.

This pattern recognition is not just a great memory tool; it’s also an integral part of the human consciousness—and, therefore, ready and waiting for use. According to neuroscientist Daniel Bor, author of The Ravenous Brain: How the New Science of Consciousness Explains Our Insatiable Search for Meaning, this skill in finding patterns plays a critical role in our experience of life. “The process of combining more primitive pieces of information to create something more meaningful is a crucial aspect both of learning and of consciousness and is one of the defining features of human experience,” he wrote. “Once we have reached adulthood, we have decades of intensive learning behind us, where the discovery of thousands of useful combinations of features, as well as combinations of combinations and so on, has collectively generated an amazingly rich, hierarchical model of the world. Inside us is also written a multitude of mini strategies about how to direct our attention in order to maximize further learning.”

Chunking serves as a kind of zip file, a compression mechanism that contains quantities of information in a compact form. Once compressed into a chunk, the information operates in our minds much like that zip file, allowing us to unpack it to use the information inside, and then put it away again as a chunk until the next time we need it.

Bor sees three parts of the chunking process:

- Searching for chunks

- Noticing and memorizing chunks

- Using chunks already built

“The main purpose of consciousness is to search for and discover these structured chunks of information within working memory, so that they can then be used efficiently and automatically, with minimal further input from consciousness,” he wrote.

If this is the case, then using chunking as a tool for increasing memory is simply a matter of giving your brain what it wants: a recognizable pattern among disparate objects that creates some kind of logical order. Once you see—or create—the order within the chaos, you have a good chance of remembering it for the long term.

How Many Chunks?

While the long-term memory has unlimited capacity for information storage, the working (short-term) memory may be even more limited than George Miller’s research originally indicated.

Studies conducted at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and published in 2011 looked closely at visual working memory in rhesus monkeys, a species with a virtually identical capacity for memories as human beings. The research started by determining that the working memory’s capacity for new information actually topped out at four items, not seven—two items for each hemisphere of the brain. The experiments required the monkeys to determine which square among four on a computer screen had changed color when they saw the squares a second time. The monkeys did fine with this task . . . until the researchers increased the number of squares on one side of the screen. The monkeys could still determine which square had changed color if it was on the side of the screen with two squares, but not if it was on the side with three squares.

You may scoff at the brain capacity of monkeys, but before you do, think about the GPS device in your own car. The device provides a significant amount of information in a small space, and for most people, it takes a moment before they can absorb all of it. The human brain simply can’t take in seven or more fields of information—current speed, miles before arrival, time of arrival, direction traveled, the map of where the car is at that moment, the current time, and traffic updates—in a single glance.

“We found that the bottleneck is not in the remembering, it is in the perceiving,” said Earl Miller, professor of neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. In essence, the study discovered that if more than two objects are placed in the same visual field, the working memory could not perceive them.

To maximize your ability to make long-term memories, use fewer objects but make them more detailed. Chunking is one of the best methods for doing this. Using this technique, you will decrease the number of items you need to hold in memory by increasing the size and capacity of each item.

Chunking Methods

How can you make chunking work for you? Let’s look at something that’s tricky for a lot of people in the later years of life: remembering the ages of all their grandchildren.

If you are particularly blessed, you may have quite a few grandchildren, so let’s start with a group of twelve. You’ve probably been trying to remember all their ages by rote, and of course, they get older every year. By grouping them into chunks, you can make this challenge a great deal easier.

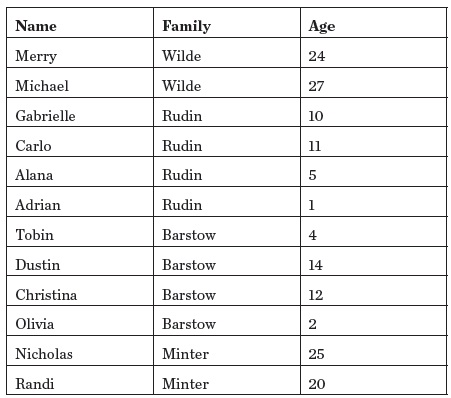

Start by listing all of these grandchildren like this:

You already have some chunks in place—knowing which children belong to which family. If that’s not helping you, however, chunking them by age group can help break down this family.

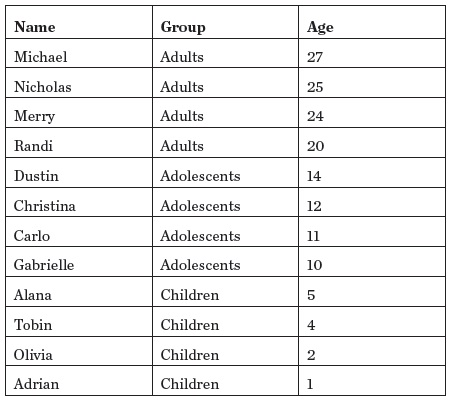

Now you have three groups: adults, adolescents, and children. In each group, you have four ages to remember:

Adults: 27, 25, 24, 20

Adolescents: 14, 12, 11, 10

Children: 5, 4, 2, 1

Suddenly this task becomes more manageable, simply because you took twelve pieces of information and reorganized them into four chunks. You don’t need to memorize mnemonic devices or prepare by committing a list of peg words to memory. You simply need to know that you have three groups of grandchildren, organized according to age.

This same principle can help you remember the shopping list discussed in Chapter Five. Do you remember the list? (Tomatoes, garlic, onions, green peppers, sausage, tomato paste, and fresh oregano.)

To divide this list into chunks, you have several methods to try.

- By category: Put all the vegetables together: tomatoes, onions, green peppers. Then group the seasonings: garlic, oregano. The packaged food: tomato paste. That leaves the only deli item: sausage.

- By area in the store: Produce: tomatoes, onions, green peppers, garlic, oregano. Deli: sausage. Shelved goods: tomato paste.

- By usage: Things to go into the sauce: tomatoes, onions, garlic, oregano, green peppers. Things that are cooked separately: sausages, tomato paste.

- By first letter: TOGGOST. Perhaps you can reorganize this into SO GOT T, turning it into three fairly easy chunks to remember.

You may even see another pattern that you would prefer. Whatever chunks you choose, they need to mean something to you—the floor plan of your favorite supermarket, the flavor palette of the food, the family recipe they will create, or the encoding that will make them most memorable for your use.

Chunking to Remember Numbers

Most people do not have to recall long strings of digits on a regular basis, but if you are required to do so in your work—or if you want to impress your friends at parties—chunking the numbers can, with practice, make you a memory master.

Perhaps you have a reason to remember a string of numbers:

384950685301

Start by breaking this string of twelve digits into two-digit chunks:

38 49 50 68 53 01

Already you can see the task becoming easier. Do any of these numbers have meaning for you? Do they represent the age of someone you know, or can you remember something you were doing at that age? If you can link each of these numbers with a meaningful memory, you can bring in your skills of association (see Chapter Five) to match the chunk with its meaning.

Are any of these pairs of numbers the birthday of a friend or relative? March 8 (3/8), April 9 (4/9), and so on, can be linked with people about whom you care enough to remember their birthdays.

You may see meaning in the numbers that others could not begin to guess. The most important thing is that you make a vivid connection that will stay with you for as long as you need to remember this string of digits.

This technique can work for long strings of words as well—particularly when the string of words is not a sentence. If you need to remember vocabulary words for an overseas trip, you can group them by general meaning, parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs), number of syllables, starting letter, or anything else that makes sense to you. This can turn a string of twenty words into five groups of four words each, making remembering them more manageable.

Chunking History

One of the daunting tasks of studying history and other global topics is remembering all of the names and how they fit into the course of events. As an example, let’s look at the generals on each side of the American Civil War.

Here’s a list of the officers in attendance at the Battle of Gettysburg, in alphabetical order:

Armistead

Buford

Chamberlain

Early

Ewell

Hancock

Heth

Hill

Hood

Meade

Lee

Longstreet

Pickett

Reynolds

Sickles

Stuart

Vincent

Warren

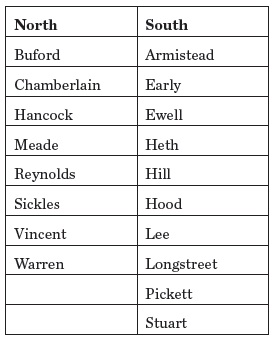

Even if you’re a Civil War buff and a history scholar, it can be difficult to keep all of these names straight. Start by breaking them up into the side on which each one fought:

This narrows down the memory work, but you’ve still got two chunks that are probably too large to remember on their own.

The list of officers in the South breaks down fairly simply into three groups:

1. Armistead, Early, Ewell (AEE)

2. Heth, Hill, Hood (HHH)

3. Lee, Longstreet, Pickett, Stuart (LLPS)

These groupings should make them much easier to remember: one with three names that start with vowels, one with three names that start with H, and four more that start with mixed consonants.

The North’s officers break down into three groups as well:

1. Buford, Chamberlain, Hancock (BCH)

2. Meade, Reynolds, Sickles (MRS)

3. Vincent, Warren (VW)

Now you can see the patterns in their starting letters. BCH may be the initials of someone you know, or you might match it with “beach,” a simple thing to remember. MRS certainly gives you an easy mnemonic, and VW—short for Volkswagen—will stick in your mind.

You still need to do some memorization to recall what each letter stands for, or what the officers’ names actually are, but now you are starting with manageable chunks of information that will become meaningful on their own as you commit them to memory.

Chunking can be an easy and handy tool for remembering all kinds of lists, numbers, and names. When you pair it with association or visualization, you can create linkages that can stay in your long-term memory for the short length of time in which you require them, or for many years to come.