Assuming that you are going to take up falconry or wish to rethink the way you house your birds, you will need numerous items to look after any bird well. These will allow you freedom from worry should you be away during the day; solve the problem of all extremes of weather affecting your bird; and enable you to cope with the bird should it, at any time, become sick or injured. Following is what I consider vital to keep a bird well and safe, allowing for most things that can happen:

a safe pen which doubles as a sheltered weathering ground to have the bird tethered, and an aviary to have it loose. This does not necessarily have the same requirements as a pen designed for captive breeding (see Chapter 5).

a reasonable sized shed or building, so that you have somewhere safe, secure and warm in case of extreme cold, for a bird that is down in weight, sick or injured.

The Pen/Weathering Ground

Unless you are flying large numbers of birds as we are here at the Centre, it is better by far to keep your bird loose in a pen, once it is trained and tame. When I first got married, and I was away from the Centre for eighteen months, I kept my birds loose in pens (while still flying them daily) even through the bad winter in 1981 and the birds did very well, probably far better than they would have done had they been tethered. You may find that if you build a really nice pen, the bird will show signs of breeding even while you are flying it. I cannot recommend too highly that it is always best to keep most flying birds loose in a safe pen if possible, rather than tethered.

As with aviaries (see Chapter 4) build for the worst of everything happening—all weather conditions, children throwing stones at the birds, etc. A friend of ours had his beautiful Imperial Eagle stoned to death in his garden in this country. Build so the bird is safe from foxes, cats, dogs, badgers, mink, magpies, crows and humans. Most of these can kill a bird up to the size of a female Goshawk; magpies and crows can steal food and your bird may only be getting a third of the food that you are giving it. Rats are capable of killing small hawks and falcons. In the United States, Great Horned Owls have been known on numerous occasions to kill tethered birds. In this country it is unlikely that this would happen as our owls are much smaller. However a Tawny Owl is capable of killing Sparrowhawks, Kestrels and Merlins if they are left unprotected at night.

Humans may well release a bird, either because they mistakenly think it wrong to tether birds, or just for the hell of it. Theft of birds is important to protect against, as is the injuring of birds by vandals, which has been known. Another friend of ours came home one evening to find his house burgled and his two American Kestrels, which were tethered on the lawn, badly hurt. The thieves had broken the birds’ wings and legs and left them there, still living. I am only glad I never knew who did it or I would have done exactly the same thing to them.

SIZE

Size is vital, if having a bird tethered. The minimum for the smallest bird is 6ft (1.9m) wide by 12ft (3.6m) deep. I would suggest that the lowest height built is above human height, thus avoiding cracked skulls. For preference I would build weathering grounds at least 8ft (2.4m) high. If housing large falcons, buzzards or hawks, the width should be at least 10ft (3m) to stop wings touching the sides, 16ft (4.9m) deep and 8ft (2.4m) high. Eagles should be given at least 15ft (4.5m) in width and 20ft (6m) from back to front, preferably 10ft (3m) in height.

FOUNDATIONS

Starting with the ground-work, build good foundations. Whatever the structure to be built, it will last longer if placed on a concrete-block foundation wall. Put a damp proof course on top of the blocks before building on up. The wall, as in our breeding pens, will stop the risk of rats, dogs or foxes digging underneath into your weathering ground, injuring or killing the bird, or making escape holes available.

Top, side and cutaway view of an ideal pen and weathering ground

SIDES

The sides of the quarters should be solid, all but the front. Facing south is best, but more important than that is that the birds should be able to see plenty going on from their quarters, reducing boredom and keeping the bird tamer. If the weather gets bad during the winter a plastic sheet can be battened onto the front. This will stop freezing winds and driving snow affecting the bird.

The sides can be built of all sorts of materials. Block-work can be continued up from the foundations; brick could be used, looking superb but very costly. Timber is probably the best choice for most people. However I would strongly advise against fence panels. Put up a decent framework and cover it with 1/2in (1.25cm) × 6in (15cm) feather edge treated that will last you years, and be far more secure.

FRONT

The front should be covered with a thick gauge weldmesh or twilweld wire. I don’t know if there is a plastic-coated weldmesh type wire of thick gauge. If there was, this would be ideal. If the wire is painted black with a bitumen paint it is much easier to see through and view the bird. Plastic-coated chain link is also a good material.

DOORS

Incorporate a double-door system. It is not safe to have just a single door. The bird, if loose, could nip past you, however tame. Make it wide and high enough for comfortable entry and preferably wide enough to push a wheelbarrow through for cleaning.

FLOOR COVERING

The reason I suggest a deep weathering ground is that I like to have it half sheltered and half open and grassed. It is vital to have a safe grass area on which to place young, newly jessed birds. They cannot hurt themselves while fighting the new jesses if they are on grass. Sand, peat or gravel can injure a bird that is struggling against the jesses for the first couple of days. We leave all our young birds on the grassed area for about a week until they have settled, only putting them on the sand area if the weather turns bad at night.

The other half of the pen is covered in about 6in (15cm) of silver sand, if you can get it, or dune sand. You can use builder’s sand which is cheaper, but it may turn the bird a lovely pink, or possibly yellow depending on the colour of the sand. I have seen gravel used, but I don’t like it for tethered birds as I think it is a little hard. If gravel is to be used, only use pea gravel which is rounded—and expensive. Peat dries out quickly, and becomes very dusty.

It is better always to place the bath on the grassed area, keeping the sand dry and the bird much cleaner.

ROOFING

At least half the pen should be roofed. It should be well shaded and not let through too much light. Overheating kills birds far quicker than cold and a tethered bird cannot move out of the sun. For choice I would use Onduline. Put a good gutter to take away excess water. The other half can be roofed either in nylon netting (see Chapter 4) or weldmesh/twilweld, again using a thick gauge.

PERCHES

If the bird is to be tethered, the perch will go centrally on the sand and similarly on the grass. If you are going to let it loose once it is tame, trained and settled, other perches will have to be placed in the pen. As you will need to tether the bird again at some time, the perches should be easily removable. They cannot be left in when the bird is re-tethered or it will constantly bate at them. One long perch under the shelter, centrally placed in wooden cups, and another towards the front should be fine.

NUMBER OF BIRDS

It is inadvisable to have more than one bird tethered in a pen. It only needs one of them to get loose and the result may well be 11⁄2 birds instead of 2. If you are housing more than one bird, double the width of the quarters and put a solid dividing wall between the birds.

One of the few times we have had a complaint about one of our birds screaming was from a gentleman who had cut down his young bird (it was still not yet feeding on the fist, but getting close). He then threw food to a Kestrel right next door, and in full view of his hungry young bird. Hardly surprising that his young bird was upset and screamed at the Kestrel for food. If one bird is cut down in weight, it is unkind and unwise to feed another in front of it.

PATHS

To avoid the weathering area getting dirty, make a good gravel, concrete or paving-stone path to it. Then, the constant use will not mean that you are ploughing through mud during wet weather to get to your bird. It will also be easier to clear snow from during prolonged bad spells.

SECURITY

Don’t forget a good lock on the outside door. I would suggest a Yale? type lock, they are less likely to freeze up than the conventional padlock. If you can afford it some sort of security system is a good idea, particularly with the increase in bird prices and the increase in the animal liberation movement. Loose birds need not be put in during cold weather, but tethered birds, particularly Lanners, Luggers and Harries Hawks, should not be left out.

HYGIENE

ALWAYS keep weathering grounds clean. Rake out and remove soiled sand daily. Have a compost heap with all soiled materials well away from where the bird is kept. Loose birds need not be put in during cold weather, but tethered birds, particularly Lanners, Luggers and Harris Hawks should not be left out.

The Shed

The shed or building for housing a bird indoors should be at least 10ft×10ft (3m×3m), giving you room to put in a sick/night quarter, plus all the equipment you will need for the bird itself. The following is what I would consider to be essential:

• A fridge for keeping food fresh and a small deep freeze to keep enough supplies of food so that you will never run out in emergencies.

• A night/sick quarter should your bird ever need to be put in because of injury, illness or very bad weather. Don’t use a tea chest, build a proper box for the job, that is easy to clean, and can’t hurt the bird in any way. Put vertical bars on the door. Information can be found in Falconry and Hawking by P. Glasier.

• A good weighing machine and weights. It is vital to check these regularly. I have known scales go out of true and kill birds because they were not checked. Never rely just on your weighing machine. Use it in conjunction with feeling and handling the bird to know how fat, or thin, or fit, it is.

• A sturdy small table on which to put the weighing machine, and to work on.

• A medicine cupboard for emergency supplies.

• Another cupboard for keeping leather, tools and various odds and sods.

• Hooks for hanging hoods, gloves, bags and unwanted intruders etc.

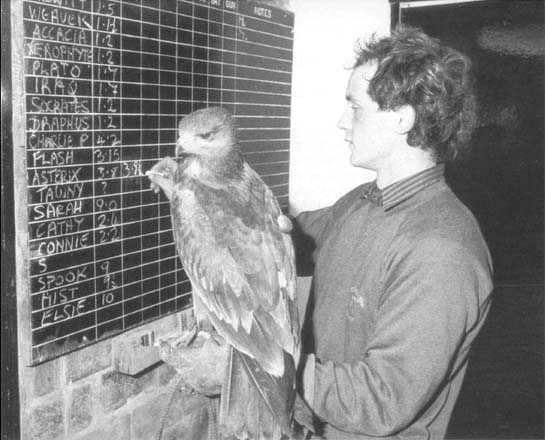

• A blackboard or wall chart for keeping weighing and performance records.

• Storage space for travelling perches, a travelling box for emergencies and so on.

• Running water and a sink.

• Electricity for lighting and heating. (Only use electricity for heating, gas or paraffin can have dangerous fumes which may affect birds.)

You may well need a bigger shed!

Simon (and Asterix) recording daily weights on the blackboard

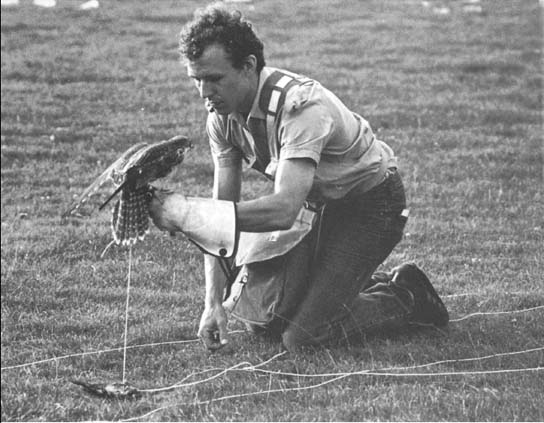

A good weighing machine is vital

Equipment for the Bird Itself

JESSES

I don’t like false Aylmeri as I have had birds catch their talons in the eyelet. Be careful to get the correct sized, well-prepared true Aylmeri as, if the eyelet is too big for the size of bird, it will wear on the back of the bird’s leg and produce a very nasty sore. Watch out for Aylmeri on tiny falcons such as Kestrels and Merlins; they are very good at pulling the leather out of the eyelet. Aylmeri are better for birds than traditional jesses as they can’t get hooked up in anything while the bird is hunting, as hunting straps are used. But Aylmeri are more inclined to break simultaneously and can, as stated, injure the bird if they are the wrong size or fitted badly. I still use traditional jesses, with short straps on some of my birds, particularly the falcons and true Aylmeri on the rest of the birds.

Tip: grease the jesses daily using Ko-cho-line. It is available from any saddlery shop, and it does not rot the leather too much. Throw the jesses away after a season’s use. Why risk them breaking just for the price of a new pair?

SWIVELS

Some are good, others are bad. Sometimes you can just be unlucky and they break for no good reason. As with jesses and leashes, this problem points to the wisdom of having the bird in a pen, whether tethered or not. In this way, even if the equipment fails, the bird cannot go anywhere. I don’t like the American barrel swivels except for the tiny ones that I use on my lureline; the jesses slip down onto the rings too easily, then the bird gets tangled. We use the D-type swivels obtainable from Martin Jones, also Robin Haigh’s Hawkmaster swivels, both of which we find are okay.

Tip: always have several spares.

‘D’ type swivels

LEASHES

Anyone who still uses the old rawhide leather leashes is round the bend and irresponsible in my opinion. You cannot tell when they are wearing out and they can snap without warning. If you lose a bird that is tethered with one of these it serves you right. The irresponsibility is that unless you find the bird, or it is very lucky, it will probably get hung up and may even die. The only bird we had to use a leather leash on was our old Changeable Hawk Eagle, Brimstone, who unravelled anything else. Now we keep her retired in a pen and don’t have the problem. Braided terylene is the material to use.

Tip: check the knot very regularly and keep leashes clean.

BELLS

The best bells I have seen, or rather heard, are Steve Little bells from the United States. They sound wonderful and are lovely to look at as well. Next come Asborno bells, also American but difficult to get. Barry Osthuizen makes good bells in Zimbabwe but he finds the materials difficult to obtain. Last but not least come the Indian bells, which are not always good and so have to be checked for sound. As they are made of far thinner material they do not last well.

Tip: we tail-bell all the birds we can, including the falcons. The bells last far longer, don’t get in the way on falcon’s stubby legs, and ring better, they can be heard from a greater distance.

HOODS

Although I do occasionally make my own hoods, lack of time means that we usually buy them. There are four main types. The Arab style, funnily enough, fits our Sakers better than others and the birds seem more comfortable in them as well. I like the less gaudy ones, but that is just a matter of taste. The Dutch style is difficult to make needing a block as does The Falconry Centre style. I prefer our own model to the Dutch, it seems to fit better and more comfortably over the eyes. Both styles will last better than any other; both have lasted years here and they get treated very hard. The Anglo-Indian are the easiest to make and are fine to use, but they tend not to fit as well as the other three.

The Americans make superb hoods, sewing them together with dental floss. Dug Pineo makes, probably, the best of all. I would very much like to learn their techniques one day, when I have the time. However, the hoods over here are good, comfortable for the birds and they work, which is the main thing.

Probably the most important tip I can offer, with hoods, is that they do not make a bird tame. I don’t like to see birds left hooded for hours. I don’t think it is kind and it doesn’t get you or the bird anywhere. Although it is useful to make most birds used to the hood so that you can use one if you need to, do not over use them. The more sights you let your bird see, the better bird it will become. It will be happier, more confident and less easy to lose. Make sure that whatever you use, it fits the bird well.

Jo with a young falcon on the creance. We get birds off the line as quickly as possible

A falcon with a Dutch hood

You can’t hood owls and it is unnecessary to hood small falcons.

Hoods if used incorrectly can kill birds. Don’t hood a bird that has not cast (brought up a pellet from the food eaten the previous day), or one with food in its crop. If the bird is sick and tries to vomit through its hood, it can easily choke to death. Never put a hooded bird down anywhere without securing it. Such birds can, and will, fly off hooded. Their chances if this happens are very slim. It should never be allowed to happen.

CREANCES

Don’t use any old piece of string or twine, get the proper material. Why risk the bird for a fiver at most? Braided terylene is good, of varying thickness depending on the bird you are going to train. I like the stick tied securely to the end of the line, preferably with the line going through a hole drilled in the stick. You have no idea how many times I have seen the line run through someone’s hands and slip out of their grasp because there was no stop at the end. Be careful, with a powerful bird pulling the line through your hand you can get a very nasty burn from the line.

Dragged Creances I don’t like them, I never use them, I won’t let my staff use them, I consider them dangerous. In the age of telemetry they are out-dated, and can upset a bird unnecessarily in the early stages of training.

LURES AND LINES

If you are going to swing a lure to any degree of accuracy or expertise, the line should be braided cotton. This will not burn your hand. People use all sorts of different things as a lure. I think some of the Americans are tops for the most amazing. I have see one brochure where the lure is a complete life-size model of whatever bird you want to hunt. How the hell you swing it, I just don’t know, and for heaven’s sake don’t accidentally hit your bird with it, death would be instantaneous. Don’t hit yourself with it either—the result could well be the same. I did hear of one chap in this country using a small yellow teddy bear as a lure, presumably because it was the same colour as a day-old chick—poor behaviour in my opinion.

A lure line

Don’t just tie chicks to a line, it looks extremely bad as far as any outsider to falconry is concerned, is unprofessional, and the chick will fall to pieces after a very short time or if the bird touches it. Remember that you are responsible for the public image of falconry wherever you are. It makes no difference if you are flying a bird for the public professionally or just training one privately for yourself, people may well still see what you are doing.

We use a pair of moorhen or magpie wings, dried in an open position, and tied back to back. They swing better than bigger wings. We then tie on a fresh piece of tough beef each day. In this way the bird gets instant reward when it catches the lure, which is light enough not to hurt the bird should you touch it by accident, and lasts well while the bird is feeding as you make in. By remaking the lure each day you also check that the line is not worn, and the meat is securely tied.

Tip: make sure that the stick is heavy enough for the bird not to carry the lure too far, but not too heavy so that it might injure the bird. Paint it a good bright colour (not red) so that you can find it easily in long grass or heather.

Dummy Rabbits Pretty basic affairs really: I have made many of the damn things. Always make them after at least three gin and tonics. The only point you have to be aware of is that if you make the dummy bunny too round it will roll when the bird grabs it, and this can cause broken tail feathers. Always put a nice lot of meat dressing on the rabbit to start with, so that the bird gets plenty of reward in the early stages, thus encouraging it greatly.

FALCONRY BAGS

It does not really matter what you use as long as you remember two things. Firstly, the bag will need two compartments, so that when you pull out the lure, you do not pull out the pick-up piece as well. If this happens, the bird is more than likely to grab the fallen piece of meat and disappear with it, leaving you feeling like a pratt of the first order. Secondly, the bag should be easy to keep clean — for the health of the bird.

GLOVES

Although you can make gloves yourself, good leather is so hard to find that it is much easier to buy them. Martin Jones makes the best I have seen in any country so far. You will only need a short glove for small falcons, small hawks or small owls. A longer single-thickness is necessary for large falcons, a double-thickness for all buzzards, large hawks and eagle owls and an eagle glove for eagles.

Falconry bags

Falconry gloves

Keep your glove as clean as possible for the health of the bird. You have got to be out of your mind if you feed day-old chicks on the fist regularly. They ruin an expensive glove quicker than almost anything. Keep all gloves away from dogs; they love them.

BLOCKS

There are various types of blocks, most of which are fine. I like uneven cork on the top of ours as it is easy to clean, warm for the birds’ feet in cold weather, and fairly soft and bouncy. You can also use Astroturf, but this needs cleaning almost daily as it collects dirt easily, I don’t use it and don’t like it. I also don’t like flat tops on my blocks, they are not as comfortable as rounded uneven topped ones.

You must always check that the top is not so narrow as to let the jesses slip down either side, thus causing the bird to straddle the block. We use blocks with a metal rod showing about 6in (15cm) above the ground, before the wooden stand. The ring moves fairly freely round this rod. The reason I use this kind is that if, by any chance, a falcon does straddle the block, all it will do is possibly damage its tail feathers against the rod. If the block is wide wood all the way to the ground, the bird’s body is held up tightly against it. We had a bird die from injured kidneys because of this. Remember though, we are probably a special case when it comes to equipment as we have up to thirty flying birds tethered during the summer, and so whatever we work with has to be designed for use with a lot of birds. Still, birds getting tangled up occasionally is a normal part of falconry—yet another good reason to keep your flying bird loose in a pen if you are able.

Three different types of falcon blocks

A well-padded indoor or outdoor perch

It doesn’t really matter what sort of block you use as long as it is safe, and comfortable for the bird. I still have not found the perfect block. Just make sure that whatever you have in the end, you keep it clean.

PERCHES

Bow Perches We have tried a number of different designs. I don’t really like the ones with a branch as the bow, partly because it is not 100 per cent safe and partly because, as the timber seasons, it gets very hard for the bird’s feet. I prefer a metal bow, made as part of the whole structure with a nicely padded, leather gripping-area for the bird — especially for birds such as Sparrowhawks, who have softer and more delicate skin than other birds. The best padding is extruded foam pipe-lagging that you can buy in metre lengths. It is soft and insulates the birds’ feet in freezing weather. The problem with a padded area is that, if it is not done well, the ring can get caught on it. Still, this is the type I prefer to use.

Ring Perches I don’t like them and I never use them.

Perches for Eagles We use very large bow perches, many of which we have had for years. We also like to have a large rock or log as an alternative perch. You can use something similar to one of those ground, screw-in dog ties, but much better made. This will hold into the ground without moving and the bird can be tethered to it easily. Don’t forget it’s there when you mow the grass, however, as it will write off a lawnmower very quickly.

I am not really happy with the various perches we have, and would like to alter all our perching for the trained birds in the Hawk Walk. We are going to rebuild the whole thing, one day when funds allow. However I am not 100 per cent sure of what I want to do yet in the way of different perching, or if my ideas will work. Several of my American friends keep their birds on a rather good indoor system, which I think might work outside, under a shelter. They have a half circle of wood, covered in carpet on the base, as a shelf on a wall. The bird can fly onto it and the area is large enough, not only for the bird to sit comfortably but to lie down if it wishes. I like this idea as many of my birds like to lie down. The bird cannot get tangled and is tethered to a fixing below where the wall meets either the floor or, when indoors, a wide table-like shelf.

I would like to do the same sort of thing on the back wall of each compartment putting the half-circle shelf about 2ft (60cm) off the ground, giving the bird a little height, which most birds like. The bird would be tethered to a fixing at the bottom of the wall, or maybe in the centre of the compartment. I would then like each bird to have the choice of two perching positions by giving a second perch in the form of a large rock or log, carefully positioned, towards the front of the compartment. We would have to make sure that the bird did not damage its feathers by hitting the forward perch. Birds in the early stages of training would have to have the more traditional perches, until they were steady enough to be moved to the new system. I don’t know if it will work, but I think it will.

BATHS

The baths I liked best were the galvanised pigeon baths produced by Eltex in Worcester and these are sadly no longer made. There are numerous people making baths from glass fibre. These are fine, if the edge is not too sharp. If the edges can be made nice and wide it is much more comfortable for the bird’s feet and better for it as well. Birds should be offered baths at least four times a week, every day if the weather is hot. Birds in a free condition in a pen should always have a bath available. Many birds will not bath, but should still be given the option if they are tethered. We have a Kestrel here who, immediately he is offered a bath, opens his wings to dry himself—he has never been known to get in. Nevertheless he is always offered one.

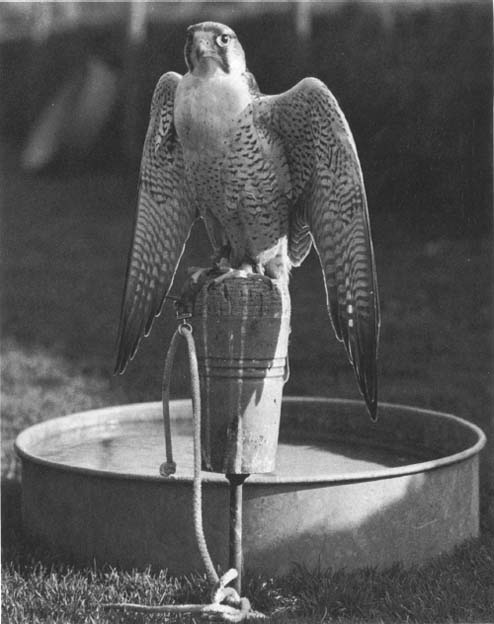

Thumbs, a Lanner, with his bath

Do not let birds bath during the afternoon in freezing conditions. I have heard of several birds that have frozen to death in the cold winters we have been having recently because idiots let them bath in the afternoon, thus not giving them time to dry before the sun went down. As birds will generally bath when the bath has just been refilled, make sure that you refill it early morning during the winter and, if possible, remove it at lunchtime. With aviary birds, the bath may not be removable; but if it is never refilled unless the sun is out, and then only in the morning, they will not normally bath. The bath will be frozen if the weather is really cold. Don’t worry about this. If the birds were in the wild in that weather the water would also be frozen and they would be unlikely to get a bath until the weather had improved. The birds most likely to bath during the winter are Peregrines and Sparrowhawks, although many of the birds that live in climates similar to ours may also do so.

If by any chance a tethered bird does get wet during the afternoon, or is not dry before nightfall, bring it in for the night and dry it with a hair dryer. Be careful not to overheat the bird, and leave it indoors in its night quarters until next morning. It would be unwise to warm a bird up with a hair dryer and then put it outside in the cold immediately.

Food

It never fails to amaze me that people will go out and buy a bird without sorting out a food supply first. I believe it is bad practice to feed birds on any one diet. We use a mixture of good beef for training and feeding on the fist, day-old cockerels, quail, rats, mice and rabbits.

DOCs have plenty of egg yolk which will provide plenty of moisture for the bird. It is interesting to note how often all birds will first eat/drink the yolk before eating the rest. As feeding DOCs on the fist is messy, we feed on the ground. There is a school of thought that says you should only feed a bird on the fist. We do not subscribe to this, for if you are not careful, it is possible to have birds such as Merlins refusing to feed unless you pick them up. This is not good policy. DOCs are not a good enough diet on their own, particularly for the accipiters, especially when they are being flown. All the hawks, even the tamest, use a tremendous amount of nervous energy, and they need a good high protein diet.

Quail suit the hawks well, with DOCs once or twice a week for the moisture content. If given to small birds such as Merlins, who are much more inclined to breed on a good quality diet, quail should be gutted and cut in half, perhaps even quarters, so they can carry it. In fact most of my falcons leave the guts. If you find that a bird never eats them you might as well gut first to save clearing up later. There is no need to feed the buzzard family vast amounts of expensive quail, as they will be just as happy on a lower-protein food source, but they and eagles benefit from the occasional rabbit. This is good for their beaks, feet and muscles.

Falcons tend not to like rats (I’m not over keen on them myself), but eagles, buzzards and the large owls do well on them and they are a more natural diet. Mice are probably the most difficult food to get anything to eat. Many birds, especially if they have been fed DOCs for a long time, will not go over to mice unless they get pretty hungry, so choose a good time of year to introduce them. Late summer, early autumn is best.

Always make sure that birds, particularly small birds in pens, will eat more that one diet. If, by any chance, your food source lets you down and you have to change diets during bad weather, birds may take too long to get used to the new food and get into dangerously low condition, they may even die. To avoid this all birds should be got used to a varied diet.

Never refreeze food, any more than you should do with food for your own consumption. Don’t feed food that has been picked up off the side of the road (road casualties). How can you know that it wasn’t run over because it was ill or poisoned? Don’t feed food that has been shot with a shotgun—lead kills. Rabbits killed with a .22 rifle are okay if the bullet has passed straight through and out.

Falconers and zoos have been very lucky for years with the price of food for their birds. Sadly this has led to some people refusing to pay more for the better quality and relatively expensive food such as quail. Even feeding quail every day (which I have suggested is not a good idea) it will still only cost about £3.50 a week for a bird up to the size of a Goshawk or Redtail. Work out how much your dog costs and you will see that the prices are not far off. If good quality birds are to be achieved, good quality feeding should be done. Doing things on the cheap is never a good idea.

Veterinary Care

Apart from sorting out good food supplies, the other vital aspect to get fixed up before a bird arrives, is a good vet. I have been told by several people that they have been turned away by vets. This may be a good thing, because if that particular vet is not interested, he or she will probably not be the man (or woman) for the job anyway. Firstly find out if you have a vet close by who is known for expertise in treating raptors, if not, the local vet should be approached. Ask him if he will take on the care of the bird in question. If the vet is not experienced (ask him) then it is very important that he will confer with a vet known for experience. If I had to move now, and didn’t have one of the super vets we have round us here, I would ask my new vet if he (or she) would mind phoning up the vet I named, to ask for advice on whatever the problem was. If he was not prepared to do this I would find one that was.

New Birds

There will come a time with every falconer or breeder when he or she will get a new bird. Whether this bird has been captive bred in this country or imported from abroad the same rules should apply. These are a few tips to go on with before even getting to the stage of collecting a bird:

1 Do your homework on the breeder you are intending to use. Make sure that there is no history of inherited problems with any of his or her birds.

2 I would strongly advise against buying a bird from a dealer, ie someone who has bought large numbers of birds in bulk from breeders and is selling them on for a higher price. You will never know what you are getting and your recourse to the law, should things go wrong, will be very much more difficult. Go direct to breeders and let us get rid of dealers altogether.

3 Get a guarantee if you are in the slightest bit worried about a bird. If the breeder will not give you a reasonable guarantee, don’t buy the bird.

4 If you are worried about health, get the bird vetted before you buy it.

5 Make sure of the price.

6 Make sure that the paperwork is available, or if for some reason it is not, get a signed piece of paper stating why not.

7 Take a good look at the bird before it goes into the box.

COLLECTING A BIRD

You would not believe what people bring to put birds in when collecting them—baskets that could be seen through by a blind bat, cardboard boxes that would be pushed to hold anything as large as a kitten, and so dilapidated that one flap of a bird’s wings and they would disintegrate. Sometimes people bring nothing at all, and very few put a piece of carpet on the floor of the box so the bird will not slip. And all this to put in a bird that might have cost them up to £2000 or perhaps more—amazing!

Take a good large box, bigger than you think the bird will need. I have already suggested that a good wooden box should always be ready in case you need it for travelling a sick bird, and perhaps this is the time to build it. After all, if you can’t afford to build a good box, you certainly won’t be able to afford a good bird. However if a cardboard box has to be used, electrical shops usually have really good ones that their equipment comes in, and they are large and very strong. If they are not keen offer them £1 for the box. Don’t then weaken the box by putting huge holes in it for air. Very few boxes are airtight anyway; a small line of holes around the top will be fine. Line the floor of the box with old clean carpet; not shagpile—that can catch in the bird’s talons. I don’t like sacking—it slips and can snag a bird’s feet. Cut the carpet to fit the box well and the bird will travel well.

Do not expect the breeder to put jesses on for you. Leather is hard to get hold of and I certainly don’t give any of mine away. Most probably don’t have the time to do it anyway. The bird will have to be handled to get it out of the box so it is just as easy to jess it up then with a friend to help you, when you get home. As we suggest not handling the bird immediately, this may not arise anyway.

Once you start your journey home don’t stop for hours at pubs or cafes. Get on with the journey and never never leave the box in the sun while in the car. I know of one bird that was dead in the box within ten miles of the start of the journey, due to overheating. Overheating will kill birds far quicker than cold. Try to make sure that you are going to arrive home during daylight hours. It gives the bird a little time to settle before dark. If you arrive after full dark, I would leave the bird in the box somewhere safe and cool until the next morning.

Any new arrival should be released into a pen. A mute sample should be collected immediately, a second one a week later. For the mute sample, plastic can be placed under a used perch in the pen and collected the next morning. These samples should then be placed in a sterile container and taken to the local poultry laboratories for testing both for worms and bacteria. This will give a good indication of the bird’s health. If you look in the Yellow Pages phone book under Poultry Laboratories which are often government testing stations, you will find the nearest one to you.

As the bird may have come from a solid-walled breeding pen, it is a good idea to put a sheet of builder’s plastic with battens on the inside of the front of the pen, before releasing the bird into it. The bird will not crash then and, if it does in the first day, it will not hurt itself. Once the bird is taken up for training the plastic can be removed, along with the perches. An imported bird will go straight into quarantine quarters, which should be ideal. The mute samples can be collected in the same way.

The bird should be fed up with as much as it will eat for at least two weeks. Never cut down a bird’s weight as soon as it arrives. Give it time to settle, get over the stress of a new home and relax. With a new bird, particularly an imported one, unless you know what it has been fed on previously, you may have to try different food types before discovering what it is happy with. Until it is settled with you, it is probably best not to change its diet.

As any bird that has been imported will be looked at by a vet on its arrival at the quarantine station, any noticeable problems should be spotted immediately. This is no bad practice and the same can be done with a new bird from this country. If there is any cause for worry, a blood sample should be taken, by a vet, and he will send it away for analysis. Because there are, sadly, some breeders who are not doing things in the most desirable way, inbreeding is probably causing some of the problems that we are seeing in both Harris Hawks and Ferruginous Buzzards. There are at least three lines of Harris Hawk that I know of which appear to have congenital problems.

Some breeders may not tell the truth as to a bird’s method of rearing. This I know through experience. Hand rearing is without doubt safer than allowing parents to do the bulk of rearing. Once the birds are back with the parents, accidents can happen. Because of this occasional loss, some breeders prefer to totally hand rear or crêche rear. I am not totally against some crêche-reared birds. Owls seem to do all right with this method. But it is not the ideal by any means and I personally would not buy a crêche-reared falcon, hawk or buzzard. Although you can breed from crêche-reared birds, if you are lucky, many are very likely to show the unpleasant side of imprinting if being flown.

If the prospective buyer is shown young grouped in a pen they will probably appear wild and thus perhaps parent reared; but only when the bird’s weight is cut down can signs of poor rearing techniques really be seen. To safeguard yourself, find out what you can of breeders’ reputations.

It never really pays to cut corners and produce poor-quality birds. Most experienced falconers know exactly which breeders they would not buy birds from. Eventually, one hopes, those producing poor birds get known, and start to have problems in disposing of their young stock. Watch out for cheaper-than-market-price birds. It can be a guide. If one goes out to buy a Labrador, most sensible people will check that the line does not have any known hip problems. If buying a horse most people have the animal vetted before even paying for it. Perhaps in this day and age we should do the same if we are not happy about a bird. The vetting will of course have to be payed for by the prospective buyer, and permission and appointments made with the breeder.

Ask for a written guarantee that the bird is not imprinted. If you find that a breeder is not prepared to do this, don’t buy the bird. To be of any use, the guarantee should last eight weeks, giving time for imprinting to show. Perhaps at this stage I had better explain a little of what we have learnt about imprinting and imprints.

IMPRINTING

I can’t think of any good reason for purposefully imprinting a bird other than to use it for artificial breeding. Therefore most of what I will discuss will be with that in mind.

Imprinting is a totally natural process. Generally speaking, it is the way that wild birds and animals keep the species pure. The young creature imprints on its parents during the first few weeks of its life, then, later, when it has become independent, and is ready to breed itself, it responds to other creatures just like its parents, who make the same vocal responses and are visually the same. In this way blackbirds don’t go off and pal up with the nearest thrush, or kestrels with merlins, thus avoiding havoc. If a young bird of prey is reared by a human the bird goes through exactly the same processes, except that it thinks it is a human. To add to that, it never goes through the growing-up period of leaving the parents and gaining independence. It will remain to all intents and purposes a baby all its life, although it may reach breeding condition.

Imprinting covers various different behaviour patterns in birds of prey. All will eventually be implemented in the breeding process. They vary in the different family groups, although probably more is known on imprinting falcons because more has been done in this field. Young birds will imprint most readily on food, then they will imprint sexually on the provider of that food. To imprint a bird well means that it must imprint on the person destined to be its future mate and must not be imprinted through food but through consistent contact, confidence and affection.

It is all too easy to imprint a bird incorrectly, making it unpleasant, unlikely to want to breed with a human, and possibly dangerous. A badly imprinted bird will scream incessantly for food, and snatch at the supposed parent for it. He or she can become aggressive if food is withheld, exactly as it does in the wild with the true parent. With increasing age the bird becomes more and more unpleasant to deal with.

But, and it is a big but, we don’t know all there is to know about imprinting yet. There is a difference between imprint behaviour and eyass behaviour. We had one experience last year which emphasises this and how little we really know. One of the young wild Peregrines at the eyrie near us was shot a few days after her first flight. The bird was found and brought to us. She was put in the sick quarters and treated but not handled, other than to examine her and keep her clean. Once recovered, she was trained to see how she could manage serious flying after a prolonged rest. She was not tamed, or handled, other than the minimum needed to get her flying loose and returning—we kept her with so little handling that she was a pig to pick up. The idea in mind was that as she was later to be sent off and returned to the wild, she must not be allowed to become too tame. The interesting fact was that this bird mantled (hid her food with wings, body and tail) quite badly both on the fist and on the ground. She never screamed or got nasty, but she did mantle over food to quite a degree. There was no way this bird was imprinted. She was hatched and reared in the wild and did not even meet mankind until she was full grown and hard down. Mantling need not be a sign of imprinting if screaming does not accompany it.

Just to really complicate matters, some falcons will begin to talk to you while being handled. Many of my birds, falcons particularly, will chat away while catching their breath between flights. They may even scream hello if they see me during the day. They are definitely not screamers, I would not keep them if they were. They don’t scream consistently for hours at a time, or even minutes, but they do like to have a quick chat during the day. Neither the odd noise from a bird, nor mantling, are necessarily signs of imprinting unless they are extreme.

There are some who imprint birds on purpose, usually for later use in artificial breeding. In the United States, it is a legal requirement to imprint all hybrid birds to stop the risk of them breeding with wild populations should they get lost, although there is little proof of this ever happening.

The Americans have perfected the art of flying imprinted birds which are also used for breeding using artificial insemination. To imprint a bird properly so that it does not scream and become a general pain in the arse, is incredibly time consuming, very messy (as it lives in the house with you to start with), easy to get wrong and personally I don’t recommend it. There are few examples of what correct, total imprinting involves.

Some total imprint birds which have been imprinted sexually on purpose for artificial breeding, will only catch one item of quarry per day as they may not like the quarry to be removed from them. It is bad practice to upset imprints. This is, I imagine, possible to get over, and the bird could be asked to catch more per day once it has settled.

A friend of mine will not tail-bell his bird because he will not cast it (hold in the hands). This might upset his bird so much that it could take months to get over it, becoming frightened of the hand. When he told me this, I thought of how I cast some of my falcons here, if they have lost a bell or need a new jess in a hurry, and then fly them five minutes later. I really could not cope with having to pander to the whims of some blasted imprint. I happen to know that the person in question does not give his dog anywhere near that leeway.

A young bird to be imprinted has to be allowed to feed at all times, but must not see the handler provide the food, it must find the food itself. Once it is starting to get about, you must let it wander around and give it hours of your time, which is both very time consuming and disastrous to furniture if you have the bird in the house. The bird must be hooded at two to three weeks old and left to get used to it for longer periods each time. You cannot break a full grown imprint to the hood—it gets very upset and this breaks the bond of confidence.

An immature male European Goshawk, bred at The National Birds of Prey Centre

European Eagle Owl (Eric & David Hosking)

A total imprint has to be reared completely away from other birds, so really only one bird can be successfully imprinted each year, in one area, by one person. If the handler doesn’t have the time and another member of the family is around more than he or she is, the bird may well imprint on them and even hate the sight of the original handler. It can take months to get an imprint to accept a different handler. Once the bird is full grown time must still be given to it daily, throughout the year, particularly coming up to the breeding season should it be required to produce either semen or eggs. Nor can the bird be left for more than a day during the breeding season, or it may switch off and take weeks to get going again.

There are many other techniques which have to be looked into before attempting to imprint a bird properly. I advise against it, although I am not really an expert on imprinting, having only done it on purpose twice. I suggest that anyone interested tries to get a copy of Falcon Propagation produced by The Peregrine Fund in the United States.

All in all, sexual imprints are very time consuming and no guarantee of captive breeding. Most of the breeding projects that were using large numbers of imprints to produce birds have, after several years, gone back to natural methods of breeding. I would far rather breed birds naturally than with artificial insemination. It is better for the birds, produces better young, is less time consuming and makes rearing 100 per cent easier. We do have two male falcons which will produce semen, but have never really used them properly. I have not flown imprints seriously, I don’t want to, and most of my friends in Britain who have flown them would prefer not to again. I know a lot of American falconers fly imprinted birds and do it very well, perhaps they have the right temperament to cope with them and I don’t.

There is, needless to say, the exception to the rule. Sparrowhawks are more fun, and appear to be more relaxed if imprinted. If you do it right they will still breed in the future. The call is a lovely noise, not at all offensive, and can be helpful as they will tell you when they are getting hungry and will call from a tree thus making it easier to locate them (see Sparrowhawk, Chapter 2). I have also found that the Black Sparrowhawk is easier to manage in this country if imprinted in a certain way.

Imprinting is a field about which we know relatively little. There are all sorts of types of imprinting. I have described some traits, and often they are unpleasant traits, which are found in the sexual imprint, as this is the bird that I consider the most difficult to cope with, apart from use as an artificial breeder.

So if you want to make sure of what you are getting—be careful and don’t rush into things just because you are desperate to have a bird. When investing money in a new captive-bred bird, it has got to be worth giving the young creature the best chance to give you all the pleasure it can, and have a happy and useful life itself. The way to avoid most bad manners is to give all young birds time to grow up. We are all too keen to start immediately young birds are hard down and can be removed from the parents. It is far wiser and better in the long run to give young birds about one month, preferably on their own in a pen, before attempting to start training. It leads to a better behaved bird who is more balanced mentally, and will be more inclined to breed at a later date.

As many breeders are very pushed for space, they are unlikely to be able to remove the young from parents and house them in another pen until they are ready to leave for new owners. They are certainly unable to house each bird separately. This is why it is so vital to have a pen/weathering ground where a young bird can be put loose for at least two weeks, preferably four, before you start the training process. This will allow about four weeks for training during which any imprinting should show, thus keeping you within the guarantee time.

Whatever bird you have and whatever sort of place you build for it, the important thing to remember is—that creature relies on you, not only for its survival, but for its quality of life. It is up to any prospective owner to make sure that quality of life is what it should be. If you can’t give a living creature the sort of care it deserves, then don’t have the creature in the first place.