In recent years, African American women have experienced the greatest increase in criminal justice supervision of all demographic groups in the United States. However, the disparity in African American women’s representation in the U.S. criminal justice system is not without historical precedent. Indeed, throughout American history, Black women, like Black men, have always been disproportionately represented in the U.S. criminal justice system. It is also important to note that while incarceration has supplanted other forms of criminal punishment in recent years, this was not always the case. In fact, in the history of punitive apparatuses the prison is a fairly modern creation that was perfected and used in greater measure in America than in Europe, where it had its origin. The advent of the prison as the primary mechanism for criminal punishment became characterized by its racial disparity in these institutions. In this section I present an overview of these developments, followed by an analysis of data and legal trends in the current era.

In the colonial era, the criminal laws were especially harsh toward enslaved persons, servants, and women and were heavily influenced by existing religious ideals.1 During this period, race gradually signified criminality among groups that previously had been considered relatively on par. For example, historian Winthrop Jordan noted that in the early seventeenth century, the terms “slave” and “servant” were used synonymously, suggesting only marginal distinctions between these two disfavored and disenfranchised groups.2 This attitude changed, however, as Africans were deemed unfit to join the community of “civilized, Christian Europeans” because of their race.3 As Judge Leon Higginbotham observed, “As it became increasingly evident that the supply of indentured servants and redemptioners was inadequate for the colonists’ maximization of their profits, a far more cruel system of human bondage was chosen—slavery, where one’s darker skin became a justification for Whites to subject Blacks to a depravity that had never been used against indentured servants.4

As greater distinctions were drawn between the servant-slave classes, criminal penalties became more disparate as well. Thus, while the typical punishments of shaming, whipping, and the death penalty were seemingly neutral potential criminal sanctions for all groups, they were meted out more frequently against enslaved persons.5 This disparity in the implementation of harsh criminal punishments occurred in both southern and northern colonial America,6 and increasingly race became the sine qua non for determining criminality and punishment. As such, early American legislatures designated behavior that may have been legal for Whites as criminal if committed by persons of African descent. As Paul Finkelman notes, “early America developed separate criminal procedures, protections, and punishments for blacks, whether slave or free. Race became the key to a fair trial and an impartial administration of the law.”7 As southern and northern colonies adopted comprehensive race-based criminal-law regimes, the notion of people of African descent as being naturally criminal was further inculcated into the evolving national consciousness. Such government-sanctioned racially discriminatory treatment also further legitimated the subordination of people of African descent in all areas of American society, not just within the criminal justice realm.

In addition to race-based punitive distinctions during the colonial era, gender also formed the basis for differential treatment. While Caucasian men and women generally received punishments such as public whippings or hangings for similar offenses, women were punished more harshly on gender bases. For instance, the punishment for adultery was more severe for White women than for White men.8 Women of African descent were not thought to possess the virtues reserved for women of European descent. Therefore, Black women were not punished more severely than Black men on the basis of gender in this regard. While gender distinctions rarely applied in the punishments meted out to enslaved men and women, the offense of miscegenation was substantially defined by one’s status as a woman of African descent.

In 1662 and 1692, for example, Virginia passed laws that outlawed interracial marriages between Whites and men and women of African descent. With respect to African American women, the 1662 act provided that “[c]hildren got by an Englishman upon a Negro woman shall be bond or free according to the condition of the mother, and if any Christian shall commit fornication with a Negro man or woman, he shall pay double the fines of the former act.”9 African women and their offspring suffered severe punishment under such statutes, as violations included physical punishment for the women and enslavement for the children determined by the mother’s status. In most instances, White men were simply fined for violating miscegenation laws.

It was clear as early as 1643 that African women occupied the lowest social status in society, as exemplified by Virginia labor tax statutes. In 1629, Virginia had designated that “tithable persons” included all those who worked the land. In 1643, however, tithable persons were redefined to include all adult men and Black women. The distinction was significant because servant women of European origin were deemed appropriately employed in domestic settings, while Black women were accorded no such regard. Instead, as John Hammond of Virginia wrote in 1656 in reference to African American women, “Yet som wenches that are nasty and beastly and not fit to be so employed are put in the ground.”10 While this was not a criminal sanction, it clearly penalized Black women on the basis of their race and gender and consigned them to harsher working conditions in the fields. In 1662, Virginia enacted a statute extending the tax on women to all “persons [who] purchase women servants to work in the ground.” Again, the racial distinctions were such that White women were tithable only if they were servants and actually worked in the fields, while women of African descent were tithable whether or not they were free.11

Once the system of chattel slavery was firmly in place in colonial America, new dimensions of race-based differential criminality and punishment emerged. Sweeping slave codes were enacted to regulate every aspect of personal status and social interaction involving enslaved persons. Black women were treated just as harshly as Black men under these provisions. In an oral history account, for example, a formerly enslaved woman named Elizabeth Sparks recalled: “Beat women! Why sure he beat women. Beat women jes’ lak men. Beat women an’ wash ‘em down in brine.”12 Under the elaborate slave code system, the racial, gender, and class status of offenders and victims determined whether cases would be heard in designated White or slave forums.13

Further, under the perverse reasoning of slave codes, enslaved persons were considered property for some purposes and persons for others. This paradox is exemplified in United States v. Amy,14 in which an enslaved woman, Amy, was accused of stealing a letter from the U.S. mail. Her attorney objected to her prosecution by arguing that she had to be considered a “person” subject to the penalties of law. Upon conviction, Amy’s appeal was heard by Chief Justice Roger Taney, who explained the enslaved person’s dual status: “He is a person, and also property. As property, the rights of [the] owner are entitled to the protections of the law. As a person, he is bound to obey the law, and may, like any other person, be punished if he offends it.”15

Significantly, persons of African descent were targeted for inhumane public and private punishment by governments and slaveholders, and official law or law enforcement rarely protected them. Thus, most slave codes permitted Whites to “beat, slap, and whip slaves with impunity.”16 If Whites faced punishment for harms to enslaved persons, it was based on the excessive cruelty of the act. Under such circumstances, however, the violation was not against the enslaved person but against the White slave owner’s property interest. Thus, fines, if assessed, were paid to the slave-owning family, not the family of the injured or murdered slave.17

Sex offenses provide the starkest example of double standards in the penalty and protection provisions of the slave codes. Under such schemes, Black men having sex with White women faced the severest penalty (hanging or castration), while White men having sex with Black women faced the lightest penalty (fines, public penance).18 Black women were completely unprotected under these legal schemes. Rape of Black women was not recognized under most slave codes and consequently could be done with impunity, whether the perpetrator was enslaved, free, or White. In George v. State,19 the court unequivocally ruled “the crime of rape does not exist in this State between Africans.” To the extent that such offenses were recognized at all, it was due to alleged property damage to slaveholders, not injury to enslaved women.

Following the end of the Civil War, African Americans fared scarcely better under new racially discriminatory criminal law provisions, as “Black Codes” replaced “slave codes.” Although the Reconstruction era reforms promised independence and self-determination for freed slaves, southern states responded by enacting laws that rein-scribed the perceived racial inferiority and inherently criminal status of people of African descent.20 Mississippi led the way by passing its laws in 1865. It became a crime there for free Blacks to commit “mischief” and make “insulting gestures,” and its Vagrancy Act defined “all free Negroes and mulattos over the age of eighteen” as criminals unless they could furnish proof of employment upon demand.21 Other states followed suit and created a variety of vaguely defined offenses directed at freed Blacks. Like the slave codes of the previous era, Black Codes were replete in their regulation of Black activity.22 As W. E. B. Du Bois stated:

All things considered, it seems probable that if the South had been permitted to have its way in 1865 the harshness of negro slavery would have been mitigated so as to make slave-trading difficult, and to make it possible for a negro to hold property and appear in some cases in court; but that in most other respects the blacks would have remained in slavery.23

In the wake of Reconstruction era failures, Jim Crow legal schemes ushered in a new era of racially biased criminal laws and other regulations restricting Black life. Characterized by apartheid-like segregation, Jim Crow laws restricted Blacks’ movement throughout the society and limited their social mobility and political exercise.24 The prospect of Black liberation and full participation in American society unleashed an especially ominous threat by the Ku Klux Klan and other White extremists, as lynching became prevalent in American society. The lives of thousands of African American men, women, and children were extinguished by lynch mobs. Officially, over three thousand lynchings were recorded between 1882 and 1964, while unofficially the figure is estimated at above ten thousand.25

While lynching was an extrajudicial punishment for supposed criminal offenses or social transgressions by African Americans, it was often carried out with tacit or express official approval. One writer notes: “Whatever the cause of lynching’s demise, the law had little or nothing to do with it. Throughout the Progressive Era, lynching remained a brutal crime that went largely uninvestigated, unprosecuted, unpunished, and undeterred by the agents of law at every level of government.”26 Offenses for which lynching was the prescribed punishment included perceived insults to White persons, to the more common allegation of rape by Black men against White women.27 Although African American men were the most frequent targets of lynchers, African American women were also targeted for mob cruelty.28 The New York Tribune reported one such incident involving the lynching of a woman:

Mississippi 1904: Luther Holbert, a Doddsville Negro, and his wife were burned at the stake for the murder of James Eastland, a white planter, and John Carr, a Negro. The planter was killed in a quarrel which arose when he came to Carr’s cabin, where he found Holbert, and ordered him to leave the plantation. Carr and a Negro, named Winters, were also killed.

Holbert and his wife fled the plantation but were brought back and burned at the stake in the presence of a thousand people. Two innocent Negroes had been shot previous to this by a posse looking for Holbert, because one of them, who resembled Holbert, refused to surrender when ordered to do so. There is nothing in the story to indicate that Holbert’s wife had any part in the crime.29

In another instance, The Crisis reported:

At Okemah, Oklahoma, Laura Nelson, a colored woman, accused of murdering a deputy sheriff who had discovered stolen goods in her house, was lynched together with her son, a boy about fifteen. The woman and her son were taken from the jail, dragged about six miles to the Canadian River, and hanged from a bridge. The woman was raped by members of the mob before she was hanged.30

Regarding these vile events, which were committed in celebratory and carnival-like atmospheres, Randall Kennedy correctly notes, “Along with the unpunished raping of black women, lynching stands out in the minds of many black Americans as the most vicious and destructive consequence of racially selective underprotection. … Nothing has more embittered discussions of the criminal justice system than the recognition that among those who have insistently demanded ‘law and order’ are those who have been unwilling to take effective action to deter antiblack racially motivated crimes.”31

Thus, enactment of racially specific criminal laws, discriminatory application of purportedly neutral criminal laws, and official failure to enforce legal protections on behalf of African Americans have created an enduring ethos of distrust of the U.S. criminal justice system within many Black communities across America. This distrust is reinforced by present circumstances in which African American men and women are disproportionately incarcerated under harsh criminal law penalties in the United States. Many share the disillusionment expressed by civil rights and antilynching advocate Ida B. Wells in 1887, which prompted her to ask, “O God, is there no redress, no peace, no justice in this land for us?”32

Discussion of the historical uses and abuses of criminal law to unfairly punish and disenfranchise Africans and Americans of African descent would be incomplete without recognition of their determined efforts at resistance throughout these periods. Throughout the assaults and indignities of the slavery era, for example, Black men and women resisted their capture in Africa and challenged the conditions of bondage once transported to the Americas.33 Both Black men and women worked primarily in the fields during slavery, although it is often perceived that Black women worked under less arduous conditions. As scholar-activist Angela Davis writes, “Where work was concerned, strength and productivity under the threat of the whip outweighed consideration of sex. In this sense, the oppression of women was identical to the oppression of men.”34 Yet, women also experienced slavery in uniquely inhumane ways that were gender specific. Indeed, once Congress prohibited further importation of Africans into the United States for enslavement, Black women’s reproductive capabilities became especially important to the slaveholders’ economic interests.

Like Black men, Black women protested their enslavement and sought freedom through various means, including “stealing, burn[ing] gin houses, barns, corncribs, and smokehouses.”35 Resistance efforts also included poisoning, arson, escape, mass revolts, and the use of physical force to kill masters.36 Historian Deborah Gray White notes that women generally had a more difficult time escaping than men.37 Nevertheless, women often employed gender-specific means to undermine their enslavement, such as avoiding or terminating pregnancy, or took other opportunities to obtain freedom.38

After emancipation, African American women remained largely in domestic service, as racism excluded them from more skilled employment opportunities. In 1881, the Atlanta washerwomen’s strike demonstrated Black women’s collective strength in demanding better pay for their work.39 In addition, African American women were prominent in the fight against lynching. Ida B. Wells, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Anna Julia Cooper, for example, were ardent advocates for African American women and men; they demanded better living and working conditions and government action to eradicate lynching.40 Black women also sought vindication of their rights through the court system, such as Ida B. Wells’s 1884 lawsuit against the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railroad, which denied her the purchase of a first-class seat. Earlier, Eliza Gallie, a free woman in Virginia, fought her accusation of petty theft in court. Historian Suzanne Lebsock writes:

In November 1853, Eliza Gallie … was arrested and charged with stealing cabbages from the patch of Alexander Stevens, a white man. She was tried in mayor’s court and sentenced to thirty-nine lashes. There was nothing unusual about this; free black women were frequently accused of petty crimes, and for free blacks as for slaves, whipping was the punishment prescribed for by law. What made the case a minor spectacle was that Eliza Gallie had resources, and she fought back.41

The racial hierarchies established during the slave era still persist in the contemporary social policies and institutions of American society, including the law. Negative stereotypes of African American women emanating from this era have also persisted.42 These images provided justifications for Black women’s continued subordination and have reduced their chances to lead healthy and successful lives. This even when in all periods in American history, African Americans have resisted negative imagery43 and demanded recognition of their political, civil, and economic rights.44 Black women led many of these early struggles and continue to assert their rights to human dignity and fair treatment within the legal and social systems in U.S. society.45

The ubiquity of prisons in American society belies the relatively recent ascendancy of this institution.46 Before the eighteenth century, prisons were only one part of the punishment system in the United States.47 Before the increased use of prisons, punishments consisted of mostly physical acts inflicted in public in order to instill humiliation and restore morality through penitence. Prison use increased in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries after reductions in the use of corporal punishment and the death penalty, and as shaming became less effective.48 After reducing the types of offenses that were punishable by death, the states determined that offenders should instead serve long prison terms.49

In the 1820s, New York and Pennsylvania developed competing models of the penitentiary, which continue to form the core philosophy and architectural structure of prisons in the United States. The New York model (Auburn Plan) was centered on the congregate system of imprisonment. Under this plan, inmates were isolated in cells, coming together for meals and work details; even then, they were forbidden to look at each other or converse.50 In contrast, the Pennsylvania model (Cherry Hill Plan) was known for its near total separation of inmates. In this regard, inmates were housed singly in cells throughout their entire confinement; they ate and worked apart from others and were allowed only selected visitors during imprisonment.51 Despite the contrasts in physical structure of the respective models, the New York and Pennsylvania models emphasized rehabilitation of the inmate by dint of a strict prison life routine. While both systems had staunch proponents, the New York model ultimately prevailed nationally as the less expensive and more profitable model.

By the post–Civil War era, overcrowding, brutality, and disorder characterized the growing prison system throughout the United States. Even in New York, inventor of the Auburn Plan with its emphasis on reflection and rehabilitation, an 1852 report to the New York legislature noted the problems associated with imprisonment. The report recognized that while prisons successfully removed the offender from society, thereby preventing further crimes during incarceration, “[i]f the object is to make him a better member of society so that he may safely mingle with it … that purpose cannot be answered by matters as they now stand.”52 Further, just after the Civil War, African Americans comprised 75 percent of prison inmates in southern states, a clear effort to replicate the conditions of slavery from the previous era. Indeed, as Edgardo Rotman notes: “The result was a ruthless exploitation with a total disregard for prisoners’ dignity and lives. The states leased prisoners to entrepreneurs who, having no ownership interest in them, exploited them even worse than slaves.”53

African Americans bore the brunt of the convict lease system, based on their massive rate of imprisonment under the Black Codes. In some states, African Americans comprised 80 to 90 percent of inmates and were the majority of inmates leased to plantations, coal mines, canal companies, brickyards, railroad companies, sawmills, turpentine farms, and phosphate mines in Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida, and the Carolinas.54 Leased convicts worked under deplorable conditions that drastically shortened their life expectancy. Financial incentives further spurred criminalization of former slaves, as the fee system enriched local deputy sheriffs, police, and judges who received per capita payments for arrests and convictions. Upon request, former slave owners, construction companies, labor contractors, or the state itself were supplied leased convicts’ cheap labor. When such needs arose, African American men and women were summarily arrested, imprisoned, and convicted. When they were predictably unable to pay their fines, they became leased convicts. As historian Bruce Franklin notes, “The convict lease system had a big advantage for the enslavers: since they did not own the convicts, they lost nothing by working them to death.”55

Key prison reforms occurred during the Progressive Era of the 1920s. In one instance, prison reform was informed by adherence to behavioral science theories, as prison reformers applied therapeutic models to inmate rehabilitation. The medical or therapeutic model was based on the belief that inmates suffered from physical, mental, and social pathology or illnesses. Despite its asserted advantages, any promise of a distinctly therapeutic approach to criminality was undermined by inadequate investment of professional resources and research on the uses of therapeutic regimens in this context. In this regard, Edgardo Rotman has noted that “the ratio of professionals to inmate (one psychiatrist or two psychologists per five hundred or one thousand cell institutions) was so small as to render the programs ineffective.”56 Additional prison reforms during the Progressive Era included increased use of indeterminate sentencing, probation, and parole. Despite these promising reforms, the therapeutic model failed due to inconsistent and ineffectual implementation.

After World War II, penology was inspired by rehabilitative optimism. Reflecting this sentiment, the American Prison Association changed its name to the American Correctional Association and advised its members to redesign their prisons as “correctional institutions” and to label the punishment blocks in them as “adjustment centers.”57 Further, this optimism was formalized in the 1955 United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which provided in Article 58 that a sentence of imprisonment can be justified only when it is used “to ensure, so far as possible, that upon his return to society, the offender is not only willing but able to lead a law-abiding and self-supporting life.”58 Prison reformers, lawmakers, and prison officials shared these principles.

The continued influence of the therapeutic model led to abuses that generated general opposition to rehabilitative ideal in the 1970s. As discussed, however, the attempts at meaningful rehabilitation were superficial at best. In addition, the prevailing indeterminate sentencing statutes led to disparities, arbitrariness, and disproportionately high penalties. After 1960, various forms of behavioral modification programs were used in American prisons. Many of these putative therapeutic programs in reality were abusive and violated inmates’ civil rights and civil liberties.

Dispelling popular perceptions, criminology professor Norval Morris states: “It would be an error to assume that most of these late-twentieth century mutations of the prison tend toward leniency and comfort. The most common prisons are the overcrowded prisons proximate to the big cities of America; they have become places of deadening routine punctuated by bursts of fear and violence.”59 Despite their proliferation from the 1800s to the present, the efficacy of the prison has been questioned during every historical period. Norval Morris and David Rothman assert that “most students of the prison have increasingly come to the conclusion that imprisonment should be used as the sanction of last resort, to be imposed only when other measures of controlling the criminal have been tried and have failed or in situations in which those other measures are clearly inadequate.”60

Women as well as men were held in the nation’s early prisons. By the mid-nineteenth century the female prisoner population had increased in several states such that women required accommodations of their own. However, while some of the stringent rules of men’s institutions did not generally apply to women, “Lack of concern, or worse, systematic exploitation meant that women often endured much poorer conditions than men convicted of similar offenses.”61

Women’s prisons lagged behind the theoretical advances of men’s prisons. For example, the Mount Pleasant Female Prison for female felons in New York was built in 1839 on the grounds of Sing Sing men’s prison nearly two decades after New York constructed the innovative male prisons at Auburn and Sing Sing.62 Mount Pleasant represented a major turning point in the development of women’s prisons because it was the first prison where women were housed in a separate building apart from men and supervised by a staff of women.63

Completely independent women’s prisons did not appear until 1870, however, when Michigan opened a “house of shelter” for women.64 In 1874, the Indiana Reformatory Institution opened as the nation’s first completely independent and physically separate prison for women. Eventually, two models of independent women’s prisons developed: custodial institutions that replicated the male penitentiary structure, and unwalled reformatories that consisted of small residential buildings strewn throughout expansive rural tracts.

Until 1870, the custodial institution was the only type of penal unit for women. According to historian Nicole Rafter, “The custodial model was a masculine model: derived from men’s prisons, it adopted their characteristics–retributive purpose, high-security architecture, a male-dominated authority structure, programs that stressed earnings, and harsh discipline.”65 By the late nineteenth century, nearly every state operated a custodial unit for women.

While the custodial female prison model continued to develop, reformatories for women also emerged. In the late 1860s, the reformatory movement grew out of the social reform activism of middle-class women who had been abolitionists and health-care workers during the Civil War. They became interested in the concerns of incarcerated women. Their reformist philosophy was reflected in the architectural design of women’s institutions, rejecting the foreboding congregate interior and walled exterior style of men’s institutions. Instead, reformers believed that unwalled facilities were more suitable for women inmates, who required fewer restrictions. This resulted in the prevalence of “cottage” plans among women’s institutions, in which groups of approximately twenty inmates resided in small buildings with a motherly matron in a familial setting.66

Women’s reformatories initially housed misdemeanants and tailored the late nineteenth-century penology of rehabilitation to perceptions of women’s unique nature. As originated by the Indiana prison, other women’s reformatories adopted the premise that women criminals should be rehabilitated rather than punished. Accordingly, it was believed that obedience and systematic religious education would help the women form orderly habits and moral values.67 In this regard, domestic training was emphasized rather than vocational skills. During their sentences the women were taught to cook, clean, and wait on table; upon parole they were sent to middle-class homes to work as servants. Hence, women’s reformatories encouraged gender-stereotyped traits of female sexual restraint, gentility, and domesticity.68

The women’s reformatory movement met its demise by 1935, after a great expansion in women’s prison building during the Progressive Era. As the population of female inmates changed, there was less sympathy for them: they were perceived as hardened offenders, unlike their young, vulnerable predecessors. Overcrowding and worsening conditions resulted from financial cutbacks while the female inmate population increased significantly. In addition, increasing numbers of African American women garnered less compassion than the previous, largely White inmate populations. Further, concerns about interracial sexual relations between inmates prompted an investigation at the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women, in New York, forcing the institution to recognize that it was no longer performing its original reformatory purpose.69 By the 1930s, it became too expensive to operate reformatories and custodial prisons for women and most states discontinued constructing them by the time of the Great Depression. Therefore, existing reformatories assumed greater numbers of more serious offenders and adopted greater punitive aspects in their overall operation. Thus, former reformatories became conventional custodial institutions upon the demise of the reformatory ideal.70

Race and class were starkly implicated in the development of women’s penal institutions. “Women’s prisons required obedience not only to prison rules … but also to cultural standards for femininity that fluctuated by race and social class.”71 These different standards regarding gender meant that racial imbalance already existed at the beginning of the growth of women’s prisons. In reality, there were two bifurcated prison systems in the United States. One system was divided along gender lines, creating different institutions for men and women; the other was subdivided along racial lines, such that men and women’s institutions were populated predominantly by African American men and women.

After the Civil War, African American women filled prisons at numbers far exceeding their representation in the general population in all geographical regions, but particularly in the South.72 White women were systematically channeled out of prisons, while African American women were systematically channeled into them. Negative racial stereotypes justified these disparities by advancing the view that White women were victims of circumstance, while African American women were captives of lesser morals and uncontrolled lust. The convict leasing system best illustrates the disparities in treatment of White and African American female offenders. For an offense such as prostitution, for example, a White prostitute normally did not receive jail time while her African American counterpart usually was sent away to hard labor.73 One example is Jane Jackson, a “colored” woman who was sentenced to ninety days, a ten-dollar fine, and court costs of fourteen dollars. When her jail term expired, she still faced and additional 240 days on the road gang to work off her twenty-four dollar debt. Historian David Oshinsky notes, “After three more brutal months, a white patron helped win Jackson a pardon by claiming, among other things, that a Negro could not be expected to control her sexual drive.”74 “I submit,” said her patron, “that she has suffered sufficiently in view of the tropical origin of her race.”75

In his study of Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Prison Farm,76 David Oshinsky notes:

Like everything else at Parchman, the women’s camp was segregated by race. The blacks lived in a long shedlike structure, the whites in a small brick building, with a high fence in between. The black population ranged from twenty-five to sixty-five women each year, the white population from zero to five. … So few white females reached Parchman that a clear profile of them is impossible. Their crimes ranged from murder and infanticide to grand larceny and aiding an escape.77

As Oshinsky further notes, “[M]ore remarkable were the white women who were spared a prison term after committing a heinous crime.” The cases of Marion Drew and Sara Ruth Dean exemplify this point:

In 1929, [Drew] confessed to killing her husband, Marlin, in Ashland, Mississippi, near the Tennessee line. … The judge had never sent a white woman to Parchman. After conferring with the district attorney, he accepted a guilty plea from Mrs. Drew and then released her without bond. She would remain free, he ordered, if she behaved herself in the future.78

A few years later, Sara Ruth Dean went on trial in 1934 for killing her married lover, J. Preston Kennedy:

The trial received national attention because both parties belonged to Mississippi’s social register, and both were physicians. Dr. Dean was accused of slipping poison into Kennedy’s whiskey glass during a “farewell midnight tryst.” … It took thirteen hours for the jury to find Mrs. Dean guilty of murder. “We hated to send a woman to prison,” said the foreman, “but we had no choice. It was either death or life imprisonment.” Another juror agreed. “We wanted to make the punishment less severe, but we could not under the verdict we had to decide on.”

Ruth Dean remained at home during her appeal. When that failed, Governor Mike Conner issued a full pardon on July 9, 1935, after being bombarded with mercy requests. Though Conner claimed to have new information “not available to the courts,” he never said what it was. His decision rested on politics and chivalry, Conner told friends. He just could not send a woman like Ruth Dean to Parchman, no matter what she had done.79

Underlying the differential treatment of women on the basis of race in the convict leasing system was the fundamental belief that some members of U.S. society were more deserving of criminal labels and harsher punishments under criminal laws. As the Parchman examples illustrate, even the most heinous offenses were deemed unsuitable for correspondingly harsh punishment if they were committed by White women. By contrast, the most minor offense alleged against or committed by African American women garnered severe punishment. In the convict leasing context, this often amounted to the death penalty, as many leased convicts were literally worked to death. Reform finally came to Parchman Farm in 1972, after the federal court, in Gates v. Collier, found numerous violations under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments at the prison.80 Despite important rulings such as Collier, which ordered improvements in prison conditions and outlawed racial segregation and discrimination in prison operations, racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice and prison systems continue to flourish. Indeed, as discussed below, such disparities in women’s incarceration rates and treatment have grown rather than diminished in modern times.

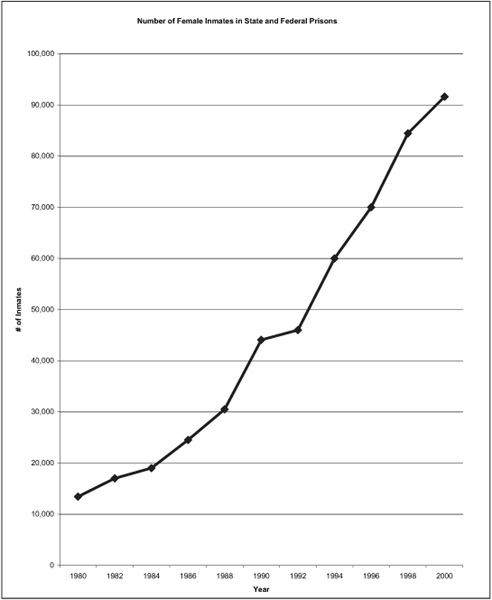

In general, women comprise a small proportion of the total U.S. prison population. As the following data reveal, however, women have been the fastest-growing segment of the prison population in contemporary times. African American women are the largest percentage of incarcerated women. As figure 1 shows, women’s overall imprisonment in state and federal institutions is characterized by sharp increases over the last twenty years. Women’s imprisonment rose from just over 13,000 in 1980 to nearly 92,000 in 2000.

Moreover, as figure 2 reveals, African American women currently comprise the majority of incarcerated women in the United States. Almost half (48 percent) of female inmates across the nation are African American, one-third (33 percent) are Caucasian, 15 percent are Hispanic, and 4 percent are women of other racial backgrounds. In the federal prison system alone, African American women comprise 35 percent of inmates, Caucasians 29 percent, Hispanic women 32 percent, and women of other racial backgrounds 4 percent.

FIG. 1. Number of Female Inmates in State and Federal Prisons Sources: GAO, Report to the Honorable Eleanor Holmes Norton, House of Representatives, Women in Prison: Issues and Challenges Confronting U.S. Correctional Systems, December 1999, at 3, 19; BJS Bulletin, Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2000, March 2001, page 5; and BJS Bulletin, Prisoners in 2000, August 2001.

FIG. 2. Percentage of State and Federal Inmate Populations by Race Sources: BJS Bulletin, Prisoners in 2000, August 2001.

Figure 3 further reveals African American women’s disproportionate representation in U.S. correctional facilities.

Next, figure 4 shows clearly that women are incarcerated primarily for nonviolent offenses. Violent crimes by women were at their highest levels in 1980, decreasing markedly since then. Property crimes also were at their highest levels in 1980 and experienced substantial decreases between 1990 and 1999. Significantly, drug-related offenses were at their lowest level in 1980; however, incarceration for drug-related offenses reached their highest level between 1980 and 1990 and continued to climb between 1990 and 1999. Similarly, public-order offenses were lowest in 1980 and faced sharp increases between 1990 and 1999. These data correspond to changes in sentencing policy that instituted longer sentences for all offenses, particularly mandatory minimum sentences for all levels of drug-related crimes.

Finally, figure 5 shows extreme differences in regional incarceration rates for women. Although all regions experienced increases between 1990 and 2000, the Northeast consistently has had the lowest number of female inmates in state and federal prisons compared to other geographical regions. The Midwest has a female population slightly greater than the Northeast, at approximately 7,000 inmates. The West had an increase of 10,000 female inmates between 1990 and 2000, placing it above both the Northeast and the Midwest. The most dramatic increase in the female prison population occurred in the South. Although there were more female inmates in 1990 in the South than in other regions, the increase climbed from just over 15,000 to nearly 37,000 incarcerated women in 2000.

FIG. 3. Number of Sentenced Female Prisoners under State or Federal Jurisdiction per 100,000 Residents, by Race, 1980, 1985, 1990–2000 Sources: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bulletin: Prisoners in 2000; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bulletin: Prisoners in 1999; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States, 1997; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bulletin: Prisoners in 1994.

FIG. 4. Type of Offense of Female Inmates in State Prison, by Percentage Sources: BJS Special Report, Women Offenders, December 1999, at 6, 14; BJS Bulletin, Prisoners in 2000, August 2001.

Why has the imprisonment of women reached such unprecedented levels? Some researchers attributed the sharp increase in women’s imprisonment to changing social mores regarding American women’s roles.81 However, the “women’s liberation theory” of women’s imprisonment ignores salient factors such as discrimination, race, poverty, and other social deprivations that account for African American women’s incarceration.82 By now, such theories are roundly discredited, as most experts acknowledge that the rise in women’s incarceration is the result of changes in the criminal laws and sentencing practices over the last twenty years. As a recent Harvard Law Review symposium stated, “[T]he reasons for the dramatic rise in women’s incarceration, both in absolute

FIG. 5. State and Federal Prisons Female Inmate Population by Region, 1990 and 2000

Sources: BJS Bulletin, Prisoners in 2000, August 2001.

terms and relating to that of men lie not primarily in changes in the seriousness of female-committed crime, but rather in changes in criminal justice policy.”83 Thus, rather than representing liberation theory, increased willingness by law enforcement to arrest and imprison women for longer periods of time represents what sociologist Meda Chesney-Lind has called “equality with a vengeance.”

These trends also reflect society’s continued willingness to equate African American women with criminality, which in turn justifies disproportionately harsh treatment of them in the criminal justice system and throughout American society. Criminologist Norval Morris recognized that the gross demographic disparity throughout the criminal justice system “may reflect racial prejudice on the part of the police, the prosecutors, the judges, and juries, so that, crime for crime, black and Hispanic offenders are more likely to be arrested by the police and are more likely to be dealt with severely by the courts.”84 The legal response to drug-related offenses provides the most glaring example of racial-gender-class bias within the criminal justice system. These issues are examined with regard to their particular impact on African American women’s lives.85

One of the hallmarks of the U.S. constitutional system is the right every American enjoys to be free from government intrusion without sufficient cause. In the area of Fourth Amendment rights, sufficient cause for government searches and seizures must be based on “individualized reasonable suspicion” of wrongdoing by law enforcement officers. These rights apparently do not extend to African American women, however, as racial-gender profiling has rendered them automatically suspect as drug couriers. While racial profiling is most often discussed in terms of affronts to African American and Latino men, experience suggests that African American and Latina American women are at greater risk for government abuse in this regard.86 One particularly egregious example of such government excess involves the U.S. Customs Service.

In March 1998, Denise Pullian returned home from a business trip to Northern Ireland, where she helped establish a program for troubled youth. A U.S. Customs agent stopped Pullian upon her arrival at O’Hare International Airport, whereupon she was told to follow the agent. Pullian was told that she was targeted for a pat search because she was wearing “loose clothing.” Upon being escorted to a small investigation room at O’Hare, Pullian’s pat search transformed into a strip search. She finally cleared customs upon being forced to remove all clothing and a tampon to satisfy customs agents that she was not carrying illicit drugs.87 When Pullian informed the Chicago NBC affiliate about her treatment, numerous African American women came forward to describe similar experiences:

WOMAN #1: I had arrived at Chicago O’Hare.

WOMAN #2: I was asked to step aside in another line.

WOMAN #3: He went through all of my luggage.

WOMAN #4: Then she told me to step this way.

WOMAN #5: “We have to go to this room because we have to search you.”

WOMAN #6: She asked me to take my clothes off, take my hair down, spread my legs apart.

WOMAN #7: And she had this great big gun strapped to her hip. So I did as she told me to do.

WOMAN #8: I took down my shorts, took down my underwear, and I had to bend over.

WOMAN #9: And then I was told to remove the pad, remove the tampon.

WOMAN #10: And then she said, “Pull up your panties and get out.” Those were her words.

WOMAN #11: You just wanted it to be over as quickly as possible.

WOMAN #12: And you feel stripped of your rights. And you get no explanation.

WOMAN #13: I felt like I was being raped.88

The Chicago-area women’s experiences were not unique. Particularly harrowing was the account by Janneral Denson, of Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Denson and her young son were stopped in February 1997 upon returning from Jamaica to Fort Lauderdale. Denson was nearly seven months pregnant at the time. She testified before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Oversight that she was stopped as she walked toward the exit with her luggage, then was searched. After being asked a series of questions about the purpose for her travel to Jamaica, she provided several pieces of documentation to verify her statements to the officers. Denson was left with another customs officer and waited, uninformed about the basis for her detention, for over an hour. Having not eaten all day, her request for food was ignored. After some time passed, she asked to go to the bathroom. She testified that she was escorted to the bathroom by two agents “where they had me lean against the wall, spread my legs, so that they could search me.” The agent then read her some legal rights from a piece of paper, which she refused to sign. Her request to speak to a lawyer was denied. Instead, she was handcuffed and driven to Miami.

Upon arrival at a Miami hospital, Denson was told to change into a hospital gown. The planned vaginal examination was not conducted because a doctor decided she was too far along in her pregnancy. Instead, she was handcuffed again and taken to the Labor/Delivery ward. After long waits, she provided blood and urine samples. She then was put on a bed and handcuffed to a bed rail. The first customs agent and the doctor returned to the room. The doctor had a portable sonogram machine to conduct an internal check. This check revealed a difficulty with Denson’s pregnancy, but it also revealed that Denson was not carrying contraband. Denson was then taken off the bed and handcuffed again. She reminded the agent that she didn’t have anything in her luggage and had nothing inside her body cavities and asked if she could go home. Again, without explanation, her request was denied.

When Denson requested something to eat, she was told that she would not get anything until morning. The doctor then brought in a substance called “Go Lyte” and Denson was ordered to drink it. She was told that she had to pass three clear stools before she could leave. She testified, “I was scared to death for my child. I told the agent, that’s a laxative and pregnant people should not take a laxative. I refused to drink it. They again handcuffed me to the bed; I laid there that night crying for a long time.”

The next morning they gave Denson a cold breakfast that she was unable to eat. She testified further, “I had some orange juice and water. At that time, I heard the first agent outside my door call me a ‘thing.’ She said ‘that thing’s been here since Friday and she won’t eat.’” That afternoon, Denson decided to drink the laxative to obtain her release. “There I was, one hand handcuffed to a bed, so scared that I drank a laxative that might hurt me and my child. I threw up. By the next morning, I passed two clear stools. About four hours later, the first agent returned to take me back to Fort Lauderdale.” Denson was held incommunicado for two days: “They say they called my mother. The truth is that they never called my mother. My mother had been calling hospitals until she found me and then an agent told her I would be at the Fort Lauderdale airport in a couple of hours. I was taken to the Fort Lauderdale airport. Nobody was there. They just left me.”89

Ms. Denson concluded her congressional testimony: “The very fact that I am here, speaking before you, points to the greatness of our country. But what I, and many other African Americans, have gone through, points to a great failure in our country. Conduct such as this is both illegal and Un-American, and, in the long run, can only serve to drive a wedge between you, the government, and the citizens of the country.”90

Aside from sharing racial heritage as African Americans, the women subjected to such searches came from wide-ranging backgrounds, including age and occupations. In defense of the agency’s actions, Customs Commissioner Ray Kelly advanced the “source country” explanation for the number of stops of African American women.91 Accordingly, travelers, presumably of all races, from countries known to produce illegal drugs are theoretically targeted in greater numbers. A number of the women had traveled from Jamaica, which is on the source country list, so this explanation may be true. However, many of the women had traveled from cities such as Barcelona, Beijing, Frankfurt, and London and were still strip searched. Therefore, it seems more plausible that the Black women were searched by U.S. law enforcement agents based on their racial and gender identities as African American women. A Harvard University statistical report determined that African American women were stopped by customs at a rate eight times greater than that for White males, even though White males far outnumber any demographic group of travelers.92 Customs’ own study revealed that in 1997, an incredible 46 percent of African American women were strip-searched at O’Hare Airport.93 Even so, Black women were found to be the least likely to be carrying drugs: at 80 percent, the percentage of negative searches was greatest for African American women.94

To add insult to injury, the Customs agency’s form letter explaining its policy to those who had been searched stated: “To be frank, we are not at all sorry. As a matter of fact, we are pleased that you have complied with our laws.”95 Not surprisingly, over ninety African American women in Chicago joined a class-action lawsuit against the U.S. Customs Service, alleging constitutional violations. According to the plaintiffs, damage awards were not their primary motivation for bringing the lawsuit; rather, they sought government accountability for their loss of dignity and fundamental civil rights in the unbridled war on drugs.96

Another aspect of the war on drugs has adversely impacted African American women as their bodies became battlegrounds for ideological wars regarding reproductive rights and drug law enforcement. Dorothy Roberts addressed this systemic bias in her groundbreaking piece, Punishing Drug Addicts Who Have Babies: Women of Color, Equality, and the Right of Privacy.97 Roberts argued that prosecution of drug-addicted mothers violated constitutional privacy and equal protection rights. Noting the government’s extensive involvement in poor African American women’s lives, as well as the women’s limited options for birth control, safe abortions, prenatal health, and drug-abuse treatment, Roberts found that “[p]oor Black women have been selected for punishment as a result of an inseparable combination of their gender, race, and economic status,” based on the “historic devaluation of African-American women’s lives and roles as mothers.”98

The problems Roberts had previously identified reappeared recently in the Medical University of South Carolina’s (MUSC) agreement to work with police and prosecutors in an effort described by Vivian Berger as “[a]n unsavory amalgam of bad law, unethical medicine, and unsound policy.”99 In 1989, MUSC devised a “test-and-arrest” scheme, according to which patients whose urine tested positive for cocaine were referred for substance-abuse treatment, and those who failed to comply or tested positive a second time were immediately taken into police custody.100 In Ferguson v. City of Charleston, S.C.,101 the U.S. Supreme Court found that the hospital’s coercive procedure to test women without a warrant, individualized suspicion, or special circumstances constituted a violation of the women’s Fourth Amendment rights. While the hospital claimed that the policy was necessary to assist doctors in treating potentially difficult or dangerous pregnancies, the same ends could have been accomplished more effectively without the specter of criminalization and unnecessary governmental intrusion. Such was the disregard for the African American women’s lives that “[s]ome were removed in hand-cuffs and shackles, still garbed in hospital gowns, bleeding and in pain from childbirth.”102 At least one woman was held three weeks in an unsanitary prison cell to await delivery of her baby.103 As Berger states, “It is hard to believe that the authorities would behave so callously if the vast majority of affected patients were not impoverished women of color.”104

While dire predictions about the harms to fetuses occasioned by maternal drug use have been overstated,105 concerns about the health of unborn and newborn babies should not be minimized. Effective responses to such concerns need not entail further criminalization of African American women’s lives, however. Notably, in Ferguson, the professed concern about African American women’s infants, if not the women themselves, occurred when “[t]here was not a single residential drug-abuse-treatment program for women in the entire state [and] MUSC itself would not admit pregnant women to its treatment center. And no outpatient program in Charleston provided childcare so that pregnant women with young children could keep their counseling appointments.”106 In emphasizing arrest and imprisonment, the MUSC policy’s absence of resources to facilitate African American women’s access to prenatal care and drug treatment exposed its punitive and racially discriminatory design.107

The Customs Service has significantly changed its search procedures according to the recommendations of an independent investigation of its practices. The new procedures emphasize behavioral indices rather than racial or ethnic factors.108 Similarly, the Medical University of South Carolina ended its racially discriminatory drug test-and-arrest policy.109 While these are welcome developments, it remains doubtful that such embedded racial biases against African American women will cease rather than resurface in new guises. Indeed, racial profiling has assumed expanded proportions in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As such, U.S. citizens, immigrants, and travelers of Middle Eastern descent have come under increased scrutiny within heightened concerns for national security.110 In this context as well, civil liberties cannot be jettisoned in finding the balance between security and liberty.111

Another area of drug-war enforcement that directly impacts on African American women’s incarceration exists in the drug sentencing disparities. As previously noted, the U.S. incarceration rate has risen faster than the crime rate; more aggressive law enforcement efforts and longer punishment for drug-related offenses help to explain this anomaly. Mandatory drug laws and minimum sentencing, three-strikes laws, and sentencing guideline schemes have resulted in a greatly increased female prison population. In New York, for example, the Rockefeller Drug Laws require mandatory prison sentences of fifteen and twenty-five years to life.112 The federal government’s adoption of mandatory sentencing for drug offenses provides the clearest example of the racial disparities that lead to African American women’s disproportionate incarceration.

Under drug laws enacted in the late 1980s, sentencing for minor roles and low-level participation in drug activities resulted in severe sentences and long incarceration for many African American and Hispanic offenders.113 On the federal level, the disparity is built into the sentencing scheme. As such, possession of five grams of crack cocaine results in a mandatory five-year sentence. In contrast, the mandatory minimum sentence for possession of 500 grams of powdered cocaine results in a five-year sentence.114 This represents a 100-fold differential in sentencing disparity between pharmacologically identical substances. The critical difference is that crack cocaine is predominant in Black and Hispanic communities and powdered cocaine in White.115 Beyond this, nothing rationally justifies the great disparity in sentencing for the two variations of this substance. Indeed, the irrational basis for the crack-powder cocaine sentencing scheme is evident in the absence of a legislative history on this crucial matter. As one commentator concluded, “Read as a whole, the abbreviated legislative history of the 1986 [Anti-Drug Abuse] Act does not provide a single, consistently cited rationale for the crack-powder penalty structure. In fact, there is evidence that Congress was simply pandering to the anti-crime attitude of the nation.”116

The life-altering consequence of Congress’s thoughtless action in consigning so many young men and women of color to prison under these laws is unconscionable, especially as the commission that recommended the scheme to Congress in the first place acknowledged the inherent unfairness of the sentencing disparities. In May 1995, the U.S. Sentencing Commission submitted a report to Congress strongly recommending abandonment of the one-hundred-to-one quantity ratio.117 The commission unanimously agreed that the ratio should be abolished but disagreed as to the appropriate ratio. A four-member majority of the commission believed that the base sentence for crack and powder cocaine should be the same.118 However, a three-member minority of the commission rejected the majority’s one-to-one recommendation, finding that substantially different “market, dosages, prices, and means of distribution” enhanced the harmfulness of crack and warranted a greater sentencing differential.119

While the three-member minority did not view the issue as having racial implications,120 others provided strong arguments to the contrary. In U.S. v. Clary,121 Judge Clyde Cahill found that the sentencing disparities for cocaine offenses evinced unconscious racism against African Americans in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. Judge Cahill thoroughly reviewed the racialized history of U.S. drug policies and the pharmacological similarities between powder and crack cocaine, and concluded that Congress’s “[f]ailure to account for a foreseeable disparate impact which would effect black Americans in grossly disproportionate numbers would … violate the spirit and letter of equal protection.”122

Despite the strength of the analysis in Clary and the obvious disproportionate impact of the cocaine sentencing laws on African Americans, neither Congress, the executive, nor the courts have deigned to redress their fundamental unfairness. In U.S. v. Armstrong,123 the Supreme Court rejected petitioners’ request for evidentiary discovery to establish their asserted equal-protection violation resulting from prosecutors’ selective drug law enforcement. The federal public defender’s office argued that African American men were selectively prosecuted under the harsher federal crack-cocaine statute. Evidence revealed that in 1991, all twenty-four federal crack-cocaine cases involved African American defendants. The public defender sought to establish that White crack-cocaine offenders were deliberately prosecuted in California state courts, where the penalties were comparatively lighter. The Court ruled that petitioners must offer minimal proof of racial discrimination prior to requiring the prosecution to disclose case records. The petitioners’ burden required “clear evidence” that the prosecutor’s selective enforcement policy “had a discriminatory effect and was motivated by discriminatory purpose.”124 As Katheryn Russell observes, “The Armstrong decision does not mean that the U.S. Attorney’s office is not selectively prosecuting Blacks in federal court. Rather, it means that the prosecutor can withhold evidence of it.”125

In addition to the basic unfairness of mandatory drug sentences, they fail to consider extenuating circumstances pertinent to women’s lives. For example, even though women generally play subordinate roles in drug operations, they often are sentenced more harshly than their more culpable male counterparts. A 1994 Department of Justice study on low-level drug offenders in federal prisons found that women were overrepresented among “low-level” drug offenders who were nonviolent, had minimal or no prior criminal history, and were not principal figures in criminal organizations or activities; nevertheless, they received sentences similar to “high-level” drug offenders under the mandatory sentencing policies.126 Further, the majority of incarcerated African American women are single parents of one or more minor children. Thus, the impact of their incarceration inures beyond the individual inmate to her children and other family members (usually maternal grandmothers), who must care for young children during the mother’s incarceration.127 African American women rarely receive lighter sentencing based on their familial relationships.128 They are also at greater risk than White women for loss of custody under the Federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA), due to the length of the drug-related sentences.129

Casualties of the war on drugs extend throughout American society, not just for African American women and members of other marginalized communities. In this regard, the erosion of basic constitutional rights through the enforcement of harsher criminal laws and penalties compromises the democratic system itself. As David Rudovsky argues, the very use of the “war” metaphor indicates tacit approval of the fact that such processes sacrifice rights.130

In addition to racially disparate legislative policies that erode our Fourteenth Amendment rights to equality and due process,131 other freedoms guaranteed by the Bill of Rights are also implicated. For example, the First Amendment’s respect for religious liberty is subordinated where religious practices conflict with the objectives of the drug war.132 The Fourth Amendment, which generally prohibits warrantless and unreasonable searches and seizures by the government, has been severely undermined, permitting law enforcement practices that regularly exceed “reasonableness” in terms of citizens’ privacy rights. In this context, in addition to the widespread use of drug-courier profiles that associate African Americans and Hispanics with drug use and trafficking, there are excessive and widespread drug-testing policies in schools and workplaces.133

Basic due process rights and the right to counsel are implicated in this war, as guaranteed by the Sixth and Seventh Amendments. As the courts are inundated with drug-related cases, the speedy trial guarantee of the Sixth Amendment and the right to a jury trial for civil matters in federal court under the Seventh Amendment are both seriously compromised.134 These developments jeopardize every citizen’s right to a fair trial.

Finally, laws that permit preventive detention and draconian punishment for drug possession denigrate the Eighth Amendment rights to bail and to sentences that are not cruel and unusual. The Bail Reform Act of 1984 similarly erodes key protections under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, as the act fundamentally changed the bail system by authorizing the pretrial imprisonment of a person innocent of any crime on the theory that he or she would likely commit other crimes while awaiting trial,135 presuming that a drug offense charge carrying a ten-year sentence makes one automatically dangerous. Accordingly, the act authorizes pretrial imprisonment based simply on a finding of probable cause for certain drug offenses. These provisions have resulted in the incarceration of thousands of drug defendants.

Predictably, the ill-advised war metaphor and its real-life consequences indeed generate casualties of war—predominantly among poor African American women who have been imprisoned in unprecedented proportions. Law and legal institutions have also suffered, however. And, while compromises to constitutional liberties may affect communities differently, the abandonment of constitutional rights has broader implications for the entire society. According to one expert, “We may soon discover that rather than freeing ourselves from drugs, we have simply given up our freedoms … our Bill of Rights and our political freedom will be the ultimate casualties of our war on drugs.”136