In the course of a duel, pistols were often shot in the air or combatants aimed merely to wound each other to satisfy their offended honor. Unlike most duels, though, the one about to unfold on this mild spring day promised to end in death. The showdown between students Louis Wigfall of South Carolina and Charles Hamer of Mississippi was to be a “duel of an unusually savage kind.”1 The students planned to shoot at each other with rifles mounted on rests from a distance of a mere ten paces. At such close range, and with the accuracy of steadied rifles, the outcome would almost certainly be fatal for one and possibly both.

At the heart of the argument between the two young men was a woman, the alluring Miss Ann Leiper. (Most upper-class women of the time, including Miss Leiper, were put on pedestals by southern men; though women had access to higher education and were encouraged to be literate, proponents of educating women often stressed “its usefulness as preparation for marriage, motherhood, and domestic life.”2 Even Jefferson, despite his farseeing views, believed women should be taught how to keep house and raise children. Dancing, drawing, and music were also acceptable subjects for women. There was no room for women at Jefferson’s university.) Professor Bonnycastle had hosted a party attended by Wigfall, Hamer, and Miss Leiper. Miss Leiper had promised Wigfall a dance. Flirtatiously, to Hamer she promised the honor of escorting her home. But as Leiper prepared to leave the party, Wigfall approached and reminded her of the promised dance. When she refused, he “very gallantly seized her hand and pulled her towards the room.”3 In front of the other partygoers, including the women, Hamer scolded Wigfall for his rudeness. Wigfall silently seethed. Hamer had berated him in public, an affront to Wigfall’s honor as heinous as a slap in the face, made all the worse by the presence of women.

The next day, Wigfall demanded that Hamer “retract” the insult. Hamer refused, saying he would only take back his statement if Miss Leiper herself agreed that Wigfall had not acted rudely. Not surprisingly, Wigfall challenged Hamer to a duel, and Hamer accepted.4 As student Henry Winter Davis of Alexandria, Virginia, noted, “The duel was the only soap for a tarnished honor.”5 The two men, both around nineteen or twenty years old, agreed to meet outside Charlottesville at a place called Old Point. One of the key rules of a proper duel was that it be a fair fight, so Wigfall, an expert pistol shot, agreed, in accordance with the code duello, to use rifles.

Wigfall, who would later achieve some fame as a southern secessionist hothead and general in the Confederate army, embraced dueling as a path to glory. One of his classmates, Charles Ellis of Richmond, recalled him as a bit of a blowhard but nevertheless sincere in his desire to fight. Wigfall, Ellis wrote in his diary, had told others “that his father and brother had been each shot in a duel and it was his wish to die thus also.”6 Though duels were often found out and those involved arrested (ten students were expelled, for instance, for a rash of proposed duels in 1840, according to school records), this duel seemed destined to happen because the two students seemed so determined to kill each other. Just two months earlier, the two antagonists had plotted an identical duel, with rifles on rests, but had been discovered. University authorities were relieved not only to have rescued the two students from injury or death but also to have saved the university’s reputation, so critical for continued state support. The duel would have proven “highly injurious” to the school, Bonnycastle noted in the daily journal that all chairmen kept.7

This second attempt at a duel by the two even more determined students—who this time had considered traveling as far as Washington—must have exasperated Bonnycastle and his colleagues. Student John Cheves, Wigfall’s fellow South Carolinian, agreed to serve as Wigfall’s second, taking on the tasks of handling the weapons, choosing a neutral location, and ensuring an impartial contest. Bonnycastle caught wind that a duel was in the works between the two foes, and he told the proctor to obtain warrants for their arrest. University officials learned that Hamer was holed up in a tavern twelve miles outside Charlottesville, so they dispatched the notoriously inept odd-jobber John Smith to arrest him. Hamer escaped. Later, authorities learned that Hamer had made his way to Richmond and that Wigfall and Cheves were riding out to meet him there. Determined to stop them, authorities sent a horseman in hot pursuit.

While students chattered about the dramatic manhunt unfolding in Richmond, they continued to deal with the pressures of their own prescribed daily routine. Student life, though violent at times, was also a gauntlet of vexatious regulations, lectures, and a routine ruled by the clock. Their straitjacket existence began with the clanging of the Rotunda bell at dawn. In their unceasing attempts to control the students, the Board of Visitors in July of 1827 had imposed an early-rising rule. Students were to be up and at their first lecture at 5:30 a.m. from late April to July. Previously, lectures had begun at 7:30 a.m. In July of 1828 the board made student life even more difficult: “The bell shall be rung every morning throughout the session, at dawn: The students shall rise at this signal & dress themselves without delay. Their room shall be cleaned and set in order, and they prepared for business, at sunrise; at which time, the Proctor shall, at least once a week, inspect their apartments.”8 Students detested the rule, especially after a night of carousing and the resultant hangovers. Janitors made random checks to roust students. Students constantly overslept and were called before the faculty to explain their slugabed behavior. Archibald Henderson of North Carolina excused his indolence by claiming that the early rising caused a pain in his chest—just as it had when he was at Yale.9 One student called the bell-ringing unjustifiable and impertinent. A hoary anecdote told by one advocate of the Early Rising Law to cajole students was that “a little boy of his acquaintance had found a bag of money by being out in time to ‘scent the morning air.’” Students responded by noting that the man who lost the bag was up even earlier.10 The despised rule created a resentment that would build throughout the years.

The students awoke to cold rooms, sometimes murky with fireplace smoke or wet from leaking roofs, new but badly constructed. The students dressed in the dim flicker of candlelight. While the young scholars groused, the black slaves, always euphemistically referred to in university records as servants, fetched water and towels for each student to wash himself. The slaves also made the beds, swept the rooms, emptied the chamber pots, removed fireplace ashes, cleaned the candlesticks, and polished students’ shoes. At times the rooms were so cold the students slept in their shoes or carried their bedding to sleep on the floor by the fireplace, dirtying the sheets, which slaves then had to wash. The dorm rooms were austere and cell-like—only 170 square feet—and sometimes shared by two students. Each room had one window and one door, and students used both as exits and entrances. The rooms typically contained a wooden table, two chairs, a washstand, a water pitcher and basin, a mirror, and a bed. A pair of tongs, andirons, and a shovel stood by the fireplace. Chamber pots were usually stowed under the bed.

Students’ attire was an ongoing source of discord. Students in the early years of the university were forced to wear uniforms, capped with a hat “round & black.”11 In December of 1826—in yet another round of rule making—the governing board prescribed in excruciating detail what had to be worn:

The dress of the students, wherever resident, shall be uniform and plain. The coat, waistcoat & pantaloons, of cloth of a dark gray mixture, at a price not exceeding $6 per yard. The coat shall be single breasted; with a standing cape, & skirts of a moderate length with pocket flaps. The waistcoat shall be single breasted, with a standing collar; and the pantaloons, of the usual form. The buttons of each garment to be flat, and covered with the same cloth. The pantaloons & waistcoat of this dress may vary with the season; the latter of which, when required by the season, may be of white; the former of light brown cotton or linen. Shoes, with black gaiters in cold weather, and white stockings in [warm] weather,—and in no case boots—shall be worn by them. The neck-cloth shall be plain black, in the cold; white, in the warm season.12

The rules demanded that students wear the austere uniform outside the precincts. Within the precincts the uniform was to be worn on Sunday, during examinations, and at “public exhibitions.”13 At all other times, within the precincts, they could wear “a plain black gown, or a cheap frock-coat.”14 The students, among them rich fops and fashion plates, bristled at the dullness of the uniform. The Visitors’ motive in imposing the dress code was twofold. Students could be easily identified as students outside the precincts, allowing authorities to keep a closer eye on them, and perhaps more important, the required attire would disguise just how rich many of the students really were. The plain dress, the visitors felt, would help fend off continuing criticism that the university was the most expensive school in America and served only the wealthy.

The extravagant fashions of the students were an easy target for critics. So alarmed were the Visitors by the students’ free-spending ways, they enacted a rule limiting clothing expenses to one hundred dollars per school year and, frustrated by the “indulgence on the part of parents,” begged fathers to stop sending money.15 The young peacocks would not be deterred. Even Poe, who was one of the poorer students, insisted on striped pantaloons and a beautiful coat. They constantly ignored the dress code, concocting fantastic excuses, some saying they were too poor to have their uniform pants patched and that tailors had lost uniforms. Others said the uniforms were too unfashionable for polite company.

Student Robert Lewis Dabney of Louisa County, Virginia, was aghast when he saw the way his classmates attired themselves. He wrote to his mother of the “extravagant manner” of his fellow students:

I will give you a list of the part of one of their wardrobes, which I am acquainted with. Imprimis, prunella bootees, then straw-colored pantaloons, striped pink and blue silk vest, with a white or straw-colored ground, crimson merino cravat, with yellow spots on it, like the old-fashioned handkerchief, and white kid gloves (not always of the cleanest), coat of the finest cloth, and most dandified cut, and cloth cap, trimmed with rich fur. They do not think a coat wearable for more than two months, and as for pantaloons and vests, the number they consume is beyond calculation. These are the chaps to spend their $1,500 or $2,000 and learn about three cents worth of useful learning and enough rascality to ruin them forever.16

The students’ desire for finery and the Visitors’ insistence on plainness would ultimately lead to one of the biggest riots in the university’s early years.

In addition to the burden of plain dress, students were also forced to eat plain food in the six “hotels” Jefferson had placed on the outer rows of dormitories. Hotelkeepers paid rent to the university and charged students for meals and other housekeeping duties. Students of all eras apparently have the same complaint about college food and its wretchedness. In fact, thirty of the fifty-two students assigned to eat at Mrs. Gray’s hotel (on the southern extreme of the Western Range) were so disgusted with the daily fare, they petitioned the faculty for relief. In another incident involving Mr. Rose’s hotel, students complained, “his coffee bad—his tea very bad and weak—has no vegetables now but rice—sometime ago greens but in very small quantities—Food dirty and filthy, frequently finds insects in it, particularly in bread.”17 Mrs. Gray was fined ten dollars by the faculty, Rose two dollars.

Another twenty-three students complained in a petition to the faculty of the food served at a Colonel Ward’s hotel: “Whereas, we the residents of eastern Range, having with all Christian patience endured, until sufferance is no longer a virtue, the imposition of tough beef, spoilt bacon, rotten potatoes, shrinking cabbage, half cooked bread, muddy coffee, bitter tea and rancid butter, in consideration of our paying Twelve dollars and a half per month—and having waited in vain for a change for the better, think it our bounden duty, for the sake of justice and for the preservation of our health, to make a report of the aforesaid treatment of our Hotelkeeper, Col. Ward.” The students asked the faculty to rebuke the wayward hotelkeeper.18 Ellis, who dined at Mrs. Gray’s, once complained that “the old Madame added a most villainous compound to our daily fare by her called Catsup.”19

Hotelkeepers, for their part, complained that profit margins were too small to buy good food. The hotelkeeper George Spotswood grumbled that he could only afford to buy food fit for a “Yankee” accustomed to nothing more than “onions, potatoes and codfish.”20

In theory, according to faculty rules, hotelkeepers were to serve meals that were plentiful and healthy, if monotonous. The faculty ordered the proctor to carry out surprise inspections of the meals.

Though hotelkeepers would occasionally turn a blind eye to the student gambling and drinking that occurred routinely in the dormitories, the sides often clashed. In one instance hotelkeeper Spotswood and a student, Thomas P. Hooe of Alexandria, Virginia, came to blows after Spotswood found dog excrement in Hooe’s dorm room and ordered him to get rid of the dog.

“I have often spoken to you to send your dog away and if you do not my servant shall not clean up your room,” Spotswood told Hooe, according to a remarkably detailed record of the confrontation. “I did not come here to clean after dogs.”

“By God I’ll flog him [the slave] if he don’t” clean up the room, Hooe replied.

“You are mistaken you sha’nt do that.”

“Begone out of the room.”

“I will go when you request me as a gentleman.”

Hooe repeated his demand several times. Spotswood stood fast.

“By G——I will make you,” Hooe said, bounding out of bed, putting on his “drawers,” and shoving Spotswood toward the door.

“Say what you please but keep your hands off,” Spotswood said. “I will not be ordered as a servant and will not go out until you ask me politely.”

“By G——I will kill you if you don’t,” Hooe said. He then seized a shovel and prepared to hit Spotswood.

“Make a sure blow or you are in danger.”

“If you were not an elderly man I should soon show you.”

“Your weakness protects you. My strength is double yours. You cannot intimidate me.”

Hooe drew back the shovel as if to swing it and an excited Spotswood exclaimed, “Put down your shovel you puppy.”

The insult was too much for Hooe. “G——D——!Do you call me puppy.”

He then struck Spotswood several times with his fist. Spotswood shoved him onto the bed, where Hooe flailed his legs. Having subdued his attacker, Spotswood held him by the feet and said, “Don’t be afraid I won’t hurt you.”

Spotswood then left the room and complained to Faculty Chairman Dunglison.21 The faculty wrote Hooe’s mother “to request her to remove him from the Institution.”22 Hooe then disappeared from school records, becoming the first and probably the last student to be expelled over an altercation involving dog excrement.

Not content to spar with hotelkeepers and each other, students sometimes brutalized the slaves who made the university run. In June 1828, student Thomas Jefferson Boyd of Albemarle County beat a slave so violently with a stick that it broke and blood ran freely from the slave’s head. When hotelkeeper Warner Minor complained to the faculty chairman, Boyd expressed his “astonishment & indignation” that Minor would complain “for so trifling an affair as that of chastising a servant for his insolence.”23 Apparently Boyd had demanded butter from the slave and felt the slave muttered insolently. Boyd later turned on Minor for complaining, calling him a coward and saying, “If you ever cross my path you or I shall die.” The faculty expressed its “high disapprobation” of Boyd but took no other action.24

But while students slept badly, ate poorly, fought constantly, lost their money at gambling, and woke with hangovers, the heaviest burden was attending class. Unlike any other university in America, Jefferson’s school offered students the choice of a field of study. Students interested in modern languages, for example, would not be compelled to take natural philosophy. The students stayed in school only as long as they wanted. The school did not bestow diplomas. Attendance was essential—unlike at other schools—because professors were required to lecture, not just read from textbooks, an innovative method of teaching in America. Classes in each of the eight subjects lasted two hours and were held three days a week.

The students’ exaggerated sense of self-importance—imbedded in their class upbringing—led them to act out in the classroom. They struck professors, walked out in the middle of lectures, chewed tobacco, scraped their feet, and otherwise acted like elementary-school boys.

Their energetic spirit led them to idolize and emulate writers like Lord Byron, famously described as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Students wanted to be like him. Byron was the most popular author among students, his books selling five times as many as any other author, including Shakespeare and Milton. Byron, an aristocratic rebel, appealed to their youthful sense of defiance. Second only to Byron was the poet Thomas Campbell, whose manly, warlike poems aroused the students’ fighting spirit.

Thomas Tucker, of Brunswick County, Virginia, was one of the miscreants who made the lives of professors miserable. In April 1828, Tucker knocked Blaettermann’s hat off after the professor accused him of making a disrespectful noise during class. “A noise is sometimes made in imitation of the drawing of a Cork from a bottle & pouring out the liquor,” according to Blaettermann’s complaint.25

But of all the bad behavior, university officials feared duels the most. A murdered student would bring unwanted attention to the students’ widespread lawlessness and bad publicity to a university bent on protecting a fragile image as a quiet “academical village.”

Aspiring duelists Wigfall and Hamer were the beneficiaries of the university’s desire to shield the school’s image. After dispatching a rider to Richmond to have the two fugitive students arrested, Faculty Chairman Bonnycastle learned from another student that the two no longer intended to duel but had fled Charlottesville only to escape indictment by a grand jury. The chairman asked the grand jury to let the matter drop. The grand jury refused. However, Bonnycastle persuaded a judge to leave the students’ fate in the hands of university officials. The judge dismissed the case.

University records are unclear as to the fate of the students, but neither one returned to school the following year. Hamer went on to become a captain in the Confederate army, while Wigfall rose to the rank of brigadier general. Wigfall ultimately fulfilled his ambition of fighting a duel. He and his opponent, Preston Brooks, were both wounded. Brooks is known to history as the South Carolina congressman who brutally beat Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner in 1856, shattering his cane in the savage attack. At Fort Sumter, Wigfall was the officer sent in to demand the surrender of Union troops, and he would earn the title “father of conscription” during the Civil War.26

An 1831 rendering of the University of Virginia creates a peaceful scene at odds with the often turbulent reality. (Engraving by W. Goodacre, printed by Fenner Sears & Co., published by I. T. Hinton & Simpkin & Marshall, London, Dec. 1831; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

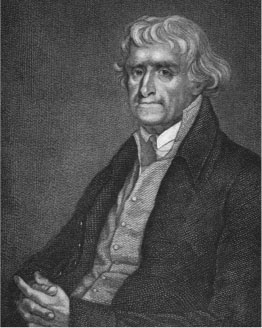

The father of the University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson. (Engraving by Neagle after the 1816 painting by Otis; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

A view of the university from the east, showing the Rotunda as Jefferson built it, with no north portico, 1849. (P. S. Duval’s Steam lith. Press, Philadelphia; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

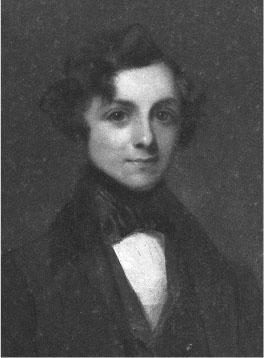

Joseph C. Cabell, Jefferson’s closest ally in creating and protecting the university. (Artist unknown, painting in Carr’s Hill Dining Room; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Professor Charles Bonnycastle was known for his acute shyness and mathematical acumen. (Artist unknown; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Math professor Thomas H. Key was appalled by student violence, but nonetheless kicked a colleague during a contentious faculty meeting. (Artist unknown, ornamental mounting credits Terence Leigh; MSS 10300-a, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Dr. Robley Dunglison, professor of medicine, also served as Jefferson’s deathbed physician. (Artist unknown, ca. 1820; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

An artistic rendering of a university student by Porte Crayon, 1853. (Copy of original; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

A view of the Rotunda and Lawn from the vicinity of Vinegar Hill, to the east, ca. 1845. (Engraving; Betts Collection #18, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

John Hartwell Cocke, an original member of the university’s Board of Visitors, staunchly supported the Uniform Law that students detested. (Daguerreotype, 1850, W. A. Retzer; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

As a student, Edgar Allan Poe witnessed, and wrote about, the vicious fights among students. (From an oil portrait by H. Inman, in the possession of Francis Howard, Esquire; Swan Electric Engraving Company; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Gessner Harrison was the first University of Virginia student to become a professor there. (Engraving by A. B. Walter; RG-30/1/6.001, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

John P. Emmet, who taught chemistry, in 1825 became the first professor to be punched by a student. (From painting by Ford, 1840; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

A rare photograph of early university students, ca. 1850. (Tintype; MSS 6776, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

The Anatomical Theatre, rebuilt after an 1886 fire. (Betts Prints 1453 &39, RG-30/1/3.821, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

An exasperated Professor William B. Rogers nearly quit because of frequent student violence. (WikiCommons)

Law professor John B. Minor’s religiosity improved the scandal-racked university’s public image. (Ca. 1859; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Professor Henry St. George Tucker became a much-needed moral compass for the university. (Artist unknown; RG 106, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

An ordained Presbyterian minister, William Holmes McGuffey was hired to teach moral philosophy at Jefferson’s secular university. (Engraving by A. B. Walter, ca. 1859; from the Bohn album, MSS 9703-g, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Chairman of the Faculty John A. G. Davis was fatally shot by a student in 1840. (Artist unknown, painting displayed at the Albemarle County Exhibit, University of Virginia Art Museum, April 1951; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

View of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and Monticello, taken from Lewis Mountain, 1856. (Edward Sachse, published by Casimir Bohn, Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Va.; Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

The north face of the Rotunda, 1900, showing the Jefferson statue by Moses Ezekiel. (Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)