16

The Feet

OUR FEET ARE AN EXTRAORDINARY piece of engineering, and they are capable of a range of subtle and delicate movements, as well as supporting our weight. They tell us what kind of ground we are standing on and how secure or insecure we feel in relation to gravity. Our feet tell us about our safety, security, and the depth of contact we have with the world outside us.

Our feet can be as sensitive and capable as our hands. The electromagnetic forces of the earth, which I believe feed our nervous system’s vital electrical energy, are filtered by concrete, rubber, and leather, so we feel—and we are—cut off and disconnected from life around us. Most of us respond by pulling away from the force of gravity—tightening our leg muscles and gripping with our toes, telling ourselves with these actions that we are alone and disconnected from our environment, and creating inside us a chronic, inexplicable sense of insecurity that can’t be changed by psychological maneuvers.

Everyone in the industrial world has weak, underdeveloped feet, no matter how athletic he or she is. Just as our present relationship with the earth is diseased, our points of contact with the earth’s surface are messed up too. Because everyone has weak feet (kyo), we don’t understand how many of the structural problems and aches and pains we have are caused by this.

The two main problems our feet have—and I don’t see much we can do to change this directly—are the flat hard surfaces we walk on most of the time and the shoes we wear. Some shoes are better than others, of course, but all shoes deprive our feet of mobility and sensitivity, dull them, and stiffen our joints.

THE PROBLEM WITH SHOES

One of the main problems that shoes create—all kinds of shoes, including excellent athletic shoes—is the relative atrophy of the foot muscles, compared to the legs. Actually, the best we can hope for from a good, well-fitted shoe is that it will strengthen our legs and maybe our ankles.

Start by taking a look at the shoes you wear most often. Also check shoes you give hard wear to, especially running shoes. Look at the soles, and notice how they’re worn. Which shoe, right or left, is worn more? That’s the side you put more weight on and lean on more. Probably the hip is higher on that side.

Then notice the front and back, inside and outside of the soles. Most people wear their shoes down more at the outside of the heel. If this is true for you, please get rid of any shoes that are worn down unevenly. If you wear your shoes down in some other way—it still may apply to you, as it applies to most people who wear shoes and walk on flat surfaces. Whenever you wear these worn-down shoes, you will distort your alignment. Inserts won’t work either—just throw them away. And don’t wear shoes you wore if you had an injury involving the lower body.

Running outside is a natural activity that most primitive people and animals do without thinking anything of it. So why do we need elaborate puffy sports shoes? Children run outside, and they don’t hurt themselves.

Thirty years ago, before people exercised in the gym much, people my mother’s age—forty-five or so—accepted the loss of abdominal tone as they got older and wore girdles. Now, fortunately, we know better and go crazy with Pilates, and so on, so we don’t sag and lose muscle tone. But it never occurs to us that what we are doing with our feet is the same pattern of submission, and we are accepting unnatural and harmful restrictions on our movement. We can hide our weak, ugly feet in a way we can’t conceal a sagging abdomen.

ALIGNMENT OF THE FEET

Most of us only become aware of the role of the feet when they develop serious problems—bunions, for example—and start hurting. Since we can’t (presumably) go without shoes and walk on rocks continually, we need to compensate by exercising and massaging the feet. So let’s look at the feet and what we can do for them.

Exercise for Aligning the Feet

Exercise for Aligning the Feet

In this exercise you need to have lines of some sort to provide a grid to align your feet with. A parquet floor is excellent, as are tiles or any other flooring with squares. A yoga mat with straight lines drawn in is ideal.

1. Stand with your feet inner-hip distance apart (that’s the space inside of the iliac crest) and the outside of each foot completely straight. The absolutely straight line of the outer edge of the foot will probably feel pigeon-toed and maybe uncomfortable to you (fig. 16.1).

Fig. 16.1. Exercise for Aligning the Feet

2. Now press the ball of the big toe into the floor, relaxing the toes.

3. You should feel the arch of the foot “dome” up away from the floor (see fig. 16.4). See if you can pull the heel isometrically toward the toes, working the transverse arch and the connective tissues, where injury or lack of tone can cause plantar fasciitis. Keep the toes relaxed!

4. Now keep the alignment and come up on the balls of your feet. You will probably want to roll outward on the feet—don’t. See if you can balance and relax your toes in this position—if you can’t balance, hold lightly on to something and try to use your foot muscles rather than your toes.

Foot Workout

Foot Workout

You can work out the feet by isolating the movements. Think how easy it is for most of us to use our fingers individually. There are the same number of nerve endings in the toes as in the fingers. Bear this in mind as you explore the possibilities of toe movement.

- Hold down all the toes except the one, or two, you want to explore, and wiggle them up, down, to the side, and so on, fast and slow, any way you can think of. You are simply stimulating a sleepy part of your nervous system. Work one foot well and notice if any other part of your body feels different. You can also try “fanning” all of your toes toward the pinky toe side, and then toward the big toe side. Try curling them and doing this, and then flexing them and doing this. Feet are usually a profound kyo (weakness), and bringing energy to them can take pain away from a jitsu (symptom) area—maybe your neck or back.

- You can also massage the connective tissue that tends to build up around the ankles by stretching the front of the foot. Keeping the foot stretched out, rub the top surface of your foot and as much of your ankle as you can reach with your knuckles. Keeping this upper area of the foot loose can prevent overcompensation in the sole of the foot, which can lead to plantar fasciitis. This technique will also help if you already have plantar fasciitis. You’ll find the same areas sensitive on the top of the foot as on the bottom.

The Ankle Joint

Now let’s look at the part of the ankle where the shinbones, tibia and fibula, connect with the interior of the heel. This joint, because we stand on it, often gets compressed, so the bones jam in together in such a way that the full range of motion is impossible. Because you can walk without much ankle flexion, you might not notice that this has happened. Instead, compression may cause pain in the feet, legs, or hips.

The bones can also be misaligned forward, backward, or to the inside or outside—pronation and supination are familiar words to sneaker buyers and runners. Forward means that the front of the foot is higher than the back. Backward means very tight calves and Achilles tendons; chronic wearers of high heels may have this problem. Pronation means that the bony protrusion on the inside of the ankle falls inward and is not level with the rest of the inner ankle. The foot tends to roll inward; probably there will be a difference on each side. Supination means just the reverse, rolling to the outside of the foot, with the bony protuberance at the outer ankle moving beyond the outside heel. Pronation often accompanies knock-knees and tight hip flexors. Supination gives you bowed legs and tight outer thighs.

Role of the Iliotibial Band

Balance on your toes for as long as you can. Notice which part of your foot you want to roll onto when it gets harder to balance. You may wobble a bit, but most people end up balancing on the outer edges of both feet. That usually feels stronger and more supportive than the inside of the foot.

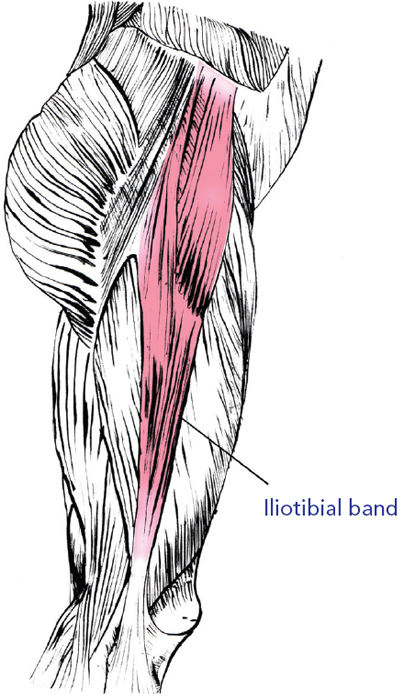

There’s a good reason for this. The outside of the leg contains a long, thin strip of connective tissue, much harder and less flexible than muscle, which runs from the hip into the knee (fig. 16.2). The purpose of this strip, called the iliotibial band, is to protect the knee from rolling outward, which would injure the meniscus. So we need it, but because we don’t move and stretch the outside of our legs very much, it tends to harden and get tight, pulling us away from the inner leg and the core of the body, onto the outside of the feet, the knees, and the hips. The knees can be pulled so far outward that they become vulnerable to injury. The core abdominal muscles are not used properly, and even the side of the neck can become tight. So you see that the way your feet contact the ground affects every structure in the body.

Fig. 16.2. Iliotibial band

The Relationship between Feet, Knees, and Hips

Now look at the other side of the foot and notice differences. Then, with your feet parallel, observe both ankles from the front. Notice the middle front part of the ankle, where the space is between the two shinbones, relative to the knees, hips, and toes. Which toes are in a line from it, and where are they relative to one another?

Now look at your feet from the back, again with your feet parallel. You’ll have to twist to see, of course, so this visual test isn’t quite as accurate. You can observe the relationship of the middle of the heel to the center of the back of the knee and see whether one or both heels turn in or out.

This will show something about the relationship between your feet, your knees, and your hips—often an uneasy alliance. Ideally, these three joints work together to maintain the stability our upper bodies need for free movement. The problems many of us have when we run come from an imbalance somewhere in these areas, where the shock absorbers of feet, knees, and hips are not in line with one another. Many factors are involved here—all the material I’ve written on the lower body will be of some relevance.

Ankle Circles

Ankle Circles

The ankle mediates between the foot, the knee, and the hip; this exercise evens out the movement of the ankles.

1. Lie on your back. Keep your kneecap pointing straight up at the ceiling and your heel as still as possible (it will move a little, but don’t let it slide at all). Most important is to keep the inner malleoli (the inside of the ankle bone that protrudes slightly) aligned; do not let one rise higher than the other (fig. 16.3). Think of a connecting line drawn between them.

Fig. 16.3. Ankle Circles

2. Now circle one ankle, pressing the heel into the ground. Try to use your foot to make the circle, rather than steering with your toes (they will help out, but try to minimize the movement). Think of a circle around the still line between the malleoli, originating in the ball of the foot. Make the circle as big as you can. Rotate in both directions for a minute or so.

3. Repeat on the other side. Usually, one side is stiffer or harder to coordinate. Repeat the exercise on the more difficult side. Your goal is to even them up.

We usually stand more on one foot than the other, and that ankle generally is less flexible, often dramatically so. This causes imbalance in the rest of the body. Keep your weight even on both feet, front and back, right and left. Notice the subtle shifts that can happen when you practice standing evenly on both legs.

THE ARCHES OF THE FEET

The three arches of the foot are equally important in their function, which is to support the weight of the body and act as shock absorbers (see fig. 16.4 below). You’ll notice that, probably due to the rolling outward that shoes encourage, many of us lose the lateral and transverse arch, only retaining the main large medial arch. Some of us lose this too.

Fig. 16.4. The three arches of the foot

Exercise for the Arches of the Feet

Exercise for the Arches of the Feet

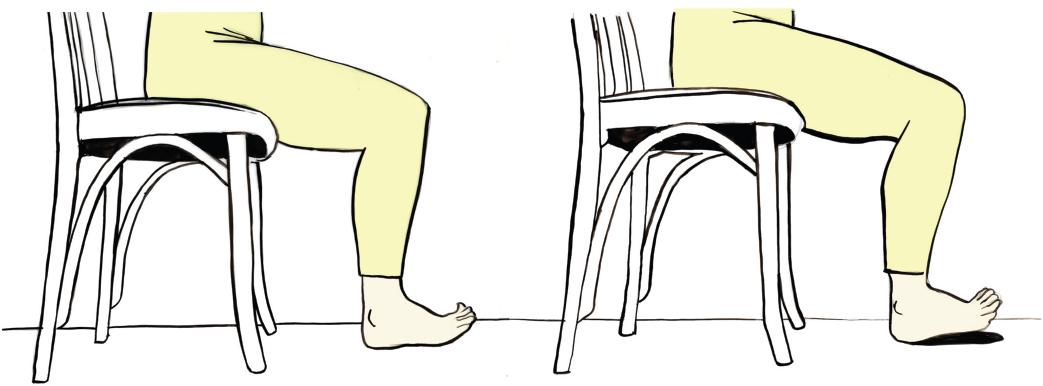

This exercise works the stirrup muscles that act as pulleys on the arches, toning them and lifting the small bones that compose the structure of the foot (fig. 16.5).

Fig. 16.5. Stirrup muscles

1. Sit in a chair with your knees and hips level, feet flat on the floor. Throughout this exercise, the inner anklebones, the knees, and (hopefully) the big toes should be together. The toes may not join if you have a bunion or hammertoes—you could place a piece of foam rubber between your toes to join them. Tie the big toes together with a rubber band. Sit up straight, keeping the big toes, inner anklebones, and knees together, and lift just the toes as high as they will go. Try to lift them together, so the outer toes come up as far as the big toe (fig. 16.6 left). Then lift up the whole foot, keeping the heels on the floor (fig. 16.6 right).

Fig. 16.6. Lift only the toes; then lift up the whole foot, heels on floor

2. Next lower just the balls of the feet, keeping the toes up.

3. Then lower the toes so your feet are back in the starting position, flat on the ground.

4. Repeat the movement—toes up, feet up, feet down, toes down. Keep each move separate and crisp, taking it for its maximum stretch. As you learn this, go slowly, concentrating on form, but aim to speed it up without losing the precision of each separate movement. Continue until your muscles are fatigued, rest 30 seconds, and repeat.

The muscles you feel working in the calves are the ones that pull up the arches of the foot. If you feel a lot of work in your groin or thighs, check that your chair is the right height—it’s probably too high. This exercise tones the stirrup muscles that pull up the arch of the foot and can correct flat feet.

THE RETINACULUM

The retinaculum is a band of fascia that encircles the ankle like a collar, protecting the ankle joint from injury. Because we don’t move our feet and ankles very much, due to walking on hard, flat surfaces in restrictive footwear, the retinaculum often gets very tight in one or all of its aspects.

When you stand normally, barefoot, you may feel tightness and pulling in one part of the ankle. This pulling will shift your weight over into that place, possibly creating other problems. A tight retinaculum can also pull the plantar fascia or the Achilles tendon on the other side of the foot and ankle, contributing to plantar fasciitis.

Sports tend to produce tightness in the front of the foot and shin, and weak muscles in those areas, combined with tightness, cause shin splints. If you suffer from shin splints, do the stretches below and the Achilles tendon stretch (see here), and then strengthen the pained shin muscles, tibialis anterior and posterior. The top of the foot gets tight mostly because we exercise wearing restrictive—supportive—footwear, which prevents full flexion of the ankle. Sedentary people who never walk usually have more flexible shins and feet—unless they drive all the time, in which case the tissue at the top of the right foot is shortened, and the ankle joint compressed on that side, from using the accelerator and brake pedals.

Deep Stretches for the Top of the Foot

Deep Stretches for the Top of the Foot

The sole of the foot receives attention in reflexology, and most of us have some awareness of it. Those reflex zones go all the way through the foot, from the sole to the top, so you are also working your whole body when you work the top of your foot.

- Bring one foot up onto a table or anything that will work for you. Roughly speaking, the higher the surface, the more of a stretch you get. The raised leg must be straight to do this one properly, so if your hamstrings are too tight to straighten the leg, you’ll need to modify (and work on your hamstring flexibility). The standing leg can be bent if you like.

- Now lean forward and press your toes down, away from you, while isometrically pressing your heel down and pulling the ankle back toward you (fig. 16.7). Make sure you get both sides of the foot, and don’t avoid the tight toes. You can press your feet down and to the side as well for a different stretch. To increase the stretch, you can place the heel of the foot you are stretching on a yoga block.

Fig. 16.7. Deep Stretches for the Top of the Foot

3. You can also work that tight fascial collar in this position. Hold onto the foot in the stretch. Then, using the knuckles of the other hand, rub all over the top, the sides, and wherever else feels good on the foot. Then work the retinaculum around the top and sides of the ankle, all the way up to the shins.

4. When you have stretched and worked one foot thoroughly, walk around and compare the two sides of your body. Notice any differences, and then repeat on the other side.

To modify: You can just press down with your hand very lightly. Lean your body up against a wall for balance if you need to—the wall should be to your side.

If you can’t straighten or raise your leg enough to open the retinaculum this way, you could sit or stand, curling the toes under, and pressing the heels forward (see fig. 16.8 below). You can roll the top of the foot on the floor to stretch evenly from the outside to the inside of the foot.

Fig. 16.8. Toes curled under

If your foot cramps, stretch the Achilles tendon and calf first. Again, walk around after you stretch your feet and notice how the rest of your body feels. You will probably have shifted your weight in some way, perhaps feeling more of the surface of your foot on the ground. You may even feel changes in your back and neck.

Runner’s Stretch

Runner’s Stretch

If you have tight hamstrings, you can stretch the front of the foot and shin successfully in a runner’s stretch.

1. With one knee bent, sit on the heel, and straighten the other leg in front of you with the foot pointed down at the floor. Bring your hand to your toes to curl them down, stretching the front of the foot (fig.16.9). You can also stretch this area while standing, by rolling the top of one foot onto a soft surface and bringing the top of the ankle forward, away from the toes.

Fig. 16.9. Runner’s Stretch

Stretch the Achilles Tendon and the Deeper Calf Muscles

Stretch the Achilles Tendon and the Deeper Calf Muscles

Most of us in this nonsquatting culture have chronically shortened Achilles tendons. We do almost nothing in our everyday lives that stretches this area.

- To determine if your Achilles tendon is shortened, see if you can squat with your hips on your heels and your feet straight out in front of you. Don’t try this if it hurts your knees or hips. The feet should be placed together. If your tendon is very short you’ll hardly be able to bring your hips down below knee level.

- You may find that you have enough flexibility to come into this position, but you can’t maintain your balance. Usually this is because the tendon isn’t flexible enough to enable you to bring your knees forward to the place where your weight is stabilized. If so, you can hold onto something in front of you and practice gradually letting go until you can maintain your position without holding on. You need to do this barefoot.

Achilles Tendon Stretch with Yoga Block

Achilles Tendon Stretch with Yoga Block

If this stretch is out of the question for you, you can bring the ball of the foot on top of a yoga block, positioning the block securely against the wall, heel on the floor with as steep an angle as is comfortable (see fig. 16.10 below). You will need to be barefoot.

- Keep the back leg straight, square the hips, and then bend the front of the knee directly forward over the ankle—no torqueing to either side. Lean forward onto the side with the bent knee to stretch. The degree of bend in the knee will determine how much you stretch your Achilles tendon and the deeper calf muscles. You will not stretch these tissues in a straight leg calf stretch.

- You may notice that the knee tracks differently over the right and left sides, wanting to turn in or out more on one side; don’t let it. The knee should track over the second toe as you look down. Alignment is important here, but make sure that when you correct this, your hips remain square to the front and your feet do not roll in or out. If the front of the foot prevents your knee coming forward, you need to stretch this area before you do this exercise.

Fig. 16.10. Stretch the Achilles Tendon and the Deeper Calf Muscles

Massaging the Top of the Foot

Massaging the Top of the Foot

While the top of your foot is stretched out in any position that works for you, you can rub that area with your knuckles. Use a small amount of cream or oil if you want. Start at the ankle, rub back and forth all around, and work the entire top of the foot. You’ll probably find some real sore spots; work them until they feel released.

You are breaking down the excess granulation in the fascia around the foot and ankle, which will free up the muscles in the top and center of the foot. Since the sole of the foot gets some movement and stretch by default—through walking on it—you will balance the structure of the connective tissue this way. You can also relieve plantar fasciitis or any problem in the sole of the foot.