Tormented by Wagner and Strauss

ON THE EVENING OF APRIL 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson left the White House for the Capitol, where he would address a joint session of Congress to ask for a declaration of war. For some two and a half anxious years, as Europe tore itself to pieces, Wilson had maintained American neutrality, and his task that night was to explain to the American people why that had become impossible and what the United States aimed to achieve by entering the Great War. To claim the president’s address was imbued with a profound sense of idealism is to understate the character of his remarks. Most famously, Wilson declared, “the world must be made safe for democracy.” Contending that the United States could not allow the violation of its “most sacred rights,” the president said he had not wanted to take the nation into the war, but that Germany, which had decided to target American ships, had left him no alternative in what he called “the most terrible and disastrous of all wars.” At the conclusion of the address, the chamber erupted in cheers and a somber Wilson, surrounded by politicians from both parties, was hailed for his efforts. Upon returning to the White House, the president remarked, “My message tonight was a message of death for our young men. How strange it seems to applaud that.”1

On that same night, music and politics intersected in New York City, where the Metropolitan Opera House was the scene of an unprecedented demonstration of patriotic fervor during a performance of The Canterbury Pilgrims, a work by the American Reginald De Koven. At the start of the fourth act, just after the intermission, Austrian conductor Artur Bodanzky strode into the orchestra pit, asked the musicians to rise, and proceeded to conduct “The Star-Spangled Banner,” with many in the audience singing energetically. (Earlier, the audience had obtained fresh copies of the newspapers’ war extras with the president’s speech, which created a wave of excitement in the theater.) When the tune ended, James Gerard, until recently America’s ambassador to Germany, rose and called out from the front of his box, “Three cheers for our president!” Loud cheering was followed by further shouts: “Three cheers for Mr. Gerard!” “Three cheers for our allies!” And finally, “Three cheers for the army and navy!” As the crowd roared, Bodanzky asked the orchestra to repeat “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

This demonstration of patriotic zeal would be followed by two freakish events. As the Berlin-born contralto Margarete Ober made her entrance as the Wife of Bath and sang her opening phrase, she collapsed on the stage with a thud. Carried off, she would not return. The performance continued in disorganized fashion, and soon thereafter the Austrian baritone Robert Leonhardt fainted backstage, much to the agitation of company members. Once revived, Leonhardt, unlike Ober, was able to complete his evening’s work, in what was surely a memorable performance on a night when American nationalism was unleashed in one of the country’s most august musical settings.2

Within days, the war declaration was passed by large margins in the House and Senate. While it would take months for the United States to train and transport thousands of troops across the Atlantic, the country was now at war, and American society would be affected in ways large and small. The unsavory passions released by war would singe the home front, with no aspect of domestic life escaping the impact of the world struggle.3

The decision to go to war would catalyze an explosion of anti-German sentiment, both ridiculous and repugnant, which would sweep across the country. If it was merely absurd to change the name of sauerkraut to “liberty cabbage” or to call German measles “liberty measles,” then it was poisonous when many school boards prohibited German-language instruction or swept German books from library shelves, a decision that, on many occasions, led to book burnings. Worse still, in April 1918 anti-German hatred caused a mob to murder a man of German descent in the small town of Collinsville, Illinois. After he was marched through the streets and forced to sing patriotic songs and kiss the American flag, Robert Prager was strung up from a tree and left to die, though the rabble allowed him to write a letter to his parents in Dresden, in which he described his fate and asked for their prayers. If the lynching of Prager, a drifter falsely accused of being a German spy, was the lone act of outright anti-German murder, the list of violent episodes would grow throughout the period of American belligerency, and included, according to one account, the stoning of dachshunds on the streets of Milwaukee.4

That German music and musicians would come under scrutiny in the United States was not surprising, though dramatic change would not immediately touch the music community. In fact, before America entered the war, from its beginning in the summer of 1914, until the end of American neutrality in the spring of 1917, performances of German music and the presence of German musicians caused little distress in the nation’s opera houses and concert halls.

Despite the pervasive fear and anxiety that would emerge later, few Americans harbored intense anti-German feelings when the First World War began in the summer of 1914. Instead, the war, which pitted Britain, France, and Russia against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and (later) the Ottoman Empire, seemed a distant eruption unlikely to touch the lives of the American people in a meaningful way. Many saw the clash of armies as yet another example of the Old World’s endless folly, and most Americans thought it was a good thing the Atlantic Ocean separated their country from the warring nations. One publication spoke confidently of America’s “isolated position,” claiming the country was in “no peril of being drawn into the European quarrel.”5

While the United States had become one of the leading players on the world stage by the early twentieth century, for Woodrow Wilson, elected in 1912 during an era of political and social reform, and for the American people, international affairs were not a central concern. And in the summer of 1914, with the start of the war, the president believed it best for the nation to remain neutral. Motivated by a genuine aversion to war, the erstwhile professor, president of Princeton, and governor of New Jersey, Wilson instructed his fellow citizens to be “impartial in thought as well as in action.”6 Across the country, there was little sense that the rhythms of daily life would be upset by the war, and people went about their business that summer and fall with a sense of detachment from Europe.

Among observers of the classical-music scene, the advent of war led to a flood of concerns, which did not foreshadow the debate on German music or the hostility toward German musicians that would occur later. The first issue of Musical America published after the war began said its impact on the concert season was unknowable. According to the journal, one of the nation’s foremost music publications, the length of the war, which many predicted would be brief, would determine its effect on American concert life. Some feared that American musicians could be marooned overseas, or in the case of male European nationals, forced to put aside their creative aspirations to shoulder a rifle. In New York, devoted listeners worried that the country’s most esteemed opera company, the Metropolitan, would have to cancel its entire season if several of its greatest figures were called to war. There was even concern that the Met’s director, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, an Italian naval engineer, would be forced to serve his country.7

As the whereabouts of artists scattered overseas became clear, even as observers acknowledged that the war would lead to interruptions in America’s musical life, they began to recognize that events abroad would not cause classical music to grind to a halt.8 But this realization did not mean the war would no longer attract attention among music commentators and musicians. To the contrary, in the conflict’s opening months, reflections on its significance continued, and a rich discussion emerged about the war’s implications for classical music in the United States. Musical America suggested it would be foolish for those involved in music to assume they could pursue lives untouched by the struggle. Musicians had “civic duties,” after all. Politics could not be shrugged off.9

In the fall of 1914, New York Philharmonic conductor Josef Stransky discussed the war’s potential for reshaping musical life. Born in Bohemia in 1872, Stransky, an Austrian citizen, had become the orchestra’s maestro in 1911, having made his name as a conductor in Prague, Hamburg, Berlin, and Dresden.10 With the world in a state of “emotional upheaval,” he observed, art’s mission is to “soothe.” The war would “stimulate art in wonderful fashion,” he claimed. Gazing hopefully toward the coming concert season, the conductor said he was optimistic not just about the Philharmonic’s health, but about the state of classical music in America.11

President Wilson’s call to remain impartial shaped the way some thought about classical music. That autumn, one of the nation’s foremost musical figures, Walter Damrosch, considered the wisdom of adhering to the president’s advice. Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Society, the city’s other leading ensemble, hailed from a family steeped in the musical world of nineteenth-century Europe. Born in Silesia in 1862, Walter was the son of the esteemed conductor Leopold Damrosch, who was close to many of the iconic musical figures of the period, including Liszt, Wagner, and Clara Schumann. Arriving in the United States in 1871, Walter would eventually become one of America’s most celebrated musical leaders. In 1878, Leopold founded New York’s Symphony Society, and in 1885, Walter became its assistant conductor.12

In October 1914, Damrosch spoke to his orchestra, which had gathered in Aeolian Hall for its first rehearsal of the season. He noted that some thirteen nationalities were represented in the ensemble, including many of those fighting in Europe. It would be wise, the conductor explained, for the men of the orchestra to follow Wilson’s instruction, and to “maintain a coherent neutrality,” even if that would be difficult for a group of artists inclined to intense feelings, and whose powerful ties bound them to their homelands.

For Damrosch, living in the United States had taught him there was “no place” for ethnic hatred. His years of service to the orchestra had demonstrated that quarrels need not arise over ethnic differences, and such a cooperative environment was attributable, he said, to an American milieu in which there was no reason one group should hate another. All that mattered in the orchestra, and by implication, in the United States, was one’s ability. Imploring his musicians to remember that they were all Americans, Damrosch said it did not matter where they were born; they should not talk about who started the war. Instead, they should be grateful to live in a “peaceful” land.13

Damrosch’s Wilsonian spirit could be heard in a thoughtful letter penned to Musical America in November 1914 by New Yorker Helene Koelling. It was essential to preserve “neutrality in art,” especially as the United States depended upon music from overseas. According to Koelling, art should be understood in universal not individual terms. It was silly for Americans to allow their views on the war to shape their attitudes about music. Koelling said the American listener had to maintain a “strict neutrality” and protect the spirit of music from being “vandalized.”14 Audiences seemed willing to go along with her suggestion.

In tracing the listening habits of American concertgoers in the period of American neutrality (through the spring of 1917), one is struck by the degree to which a passion for German music remained untouched by the carnage on Europe’s battlefields. Before America went to war, the country’s hunger for the music of Germany remained insatiable. This was despite reports of German atrocities against civilians on land and murderous acts at sea, which led to the death of noncombatants, as German submarines sank not just military vessels but freighters and passenger ships, as well.15 Still, there was “no surer magnet” for attracting large audiences than an all-Wagner symphonic concert or a Wagner opera. Indeed, Josef Stransky played nothing but Wagner with the New York Philharmonic on the orchestra’s highly popular Saturday evening series.16 And there was nothing unusual about this enchantment with Wagner, for as music historian Joseph Horowitz has so memorably shown, American music lovers had been captivated by the German’s music, which had garnered a cult-like following in the United States since the late nineteenth century.17

On Thanksgiving Day 1914, the Metropolitan performed Parsifal, which had become a company tradition. Aside from scolding some in the audience for flouting convention by applauding at inappropriate moments, one critic saluted the artists for offering a “moving performance,” which allowed the spirit of Wagner to ring out. In an obvious reference to the war, the reviewer claimed the power of the performance was fortified by the connection between the plot line of the drama, based on an epic medieval poem about the search for the Holy Grail, and contemporary events, granting the work a “transcendent splendor.”18

Six months later and a few hundred miles to the north, thousands thrilled to an outdoor performance of the composer’s Siegfried in Harvard Stadium. The event, which included contributions by some of the leading singers from the Metropolitan, was preceded by enormous excitement. Music shops displayed plot summaries, musical scores, and pictures of the composer. Hotel lobbies, railway stations, and trolley cars were plastered with announcements of the performance that June, and special trains were arranged to carry listeners to the stadium. The atmosphere, one writer declared, was “Bayreuthian.”19 The coming performance was reportedly the start of an annual tradition that would allow Wagner devotees to hear a work by the composer each season. Despite the venue’s less-than-perfect acoustics, the audience listened in an “almost awe-inspiring silence.”20 The bloodletting in Europe was a distant distraction.

Even two years into the conflict, with evidence of Germany’s wartime brutality firmly established, Wagner fever persisted, a point illustrated by the glowing response to an October 1916 concert performance in Boston by the esteemed local orchestra, which saw the celebrated German soprano Johanna Gadski offer excerpts from Tristan and Isolde. The press spoke with unrestrained praise about the quality of her singing and the orchestral playing. As for the synergy between Gadski and the Boston Symphony, which was led by the German conductor Karl Muck, another reviewer exulted, her “voice exchanged with the orchestra gold for gold and held its gleam against all the brightness that violins [and] trumpets . . . could shed.” While the time would come when Muck and Gadski would be engulfed by a storm of anti-German hatred, with America at peace, both received unstinting praise.21

In these years, the German presence in America was considerable; more than 2.3 million German immigrants lived in the United States in 1917, a figure representing the largest number of foreign-born residents in the nation. Moreover, Germans had long maintained a high profile in North America, having journeyed to the continent in significant numbers for centuries, the first arrivals immigrating to the colonies in the seventeenth century. Between 1850 and 1900, their number would never fall below one-quarter of the total of foreign-born people in the country. By the turn of the century, as one historian has observed, the American public had come to see the Germans as an especially “reputable” immigrant group. Among older Americans, they were perceived as “law-abiding” and “patriotic.” Rising from the working class, they had become “businessmen, farmers, clerks,” and skilled workmen.22

Illustrating this benign view, nineteenth-century American school textbooks characterized Germans as “hard-working, productive, thrifty, and reliable,”23 while students in US public high schools studied the German language in increasing numbers from the late nineteenth century to the start of the First World War. In 1890, 10.5 percent of high school students studied German, a number that climbed to 24 percent in 1910, about twice the number as those studying French.24

In light of their history in America over some three centuries, what befell the German people in the United States during the First World War was striking. One historian has pointed to a “spectacular reversal [in] judgment” on the part of the American people.25 But some scholars have suggested the wartime eruption of anti-German feeling was not entirely surprising; they have identified an increase in such sentiment in the United States in the late nineteenth century, which intensified as the diplomatic sky darkened in the years before the war. Though the 1870s was a harmonious period between the two countries, a time when most Americans saw Germany as a land of “poets, musicians, writers, philosophers, and scholars,” this amity would not last. By the 1880s, according to this less sanguine view, such positive perceptions had waned, as Washington and Berlin began to see one another as rivals. By the last years of the nineteenth century, some Americans believed Germany threatened US economic and foreign policy interests in the Western Hemisphere, and a series of diplomatic incidents led to the appearance of harsh anti-German stories in the American press, which began referring to “Huns” in assessing Germany’s behavior. Moreover, Americans who feared radical foreign ideologies in an age of violent struggle between labor and capital came to see German Americans as carriers of dangerous ideas. With this in mind, just before the world war, the American public’s attitude toward Germany could best be described as unsettled.26

In reflecting on wartime anti-Germanism, one should also recall that the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed a virulent strain of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, which prepared the ground for the hostility German Americans would experience during the war.27 By any measure, the period from 1880 to 1920, in which more than twenty million immigrants landed in America, was marked by extraordinary xenophobia, which manifested itself in unbridled hostility toward the so-called “new immigrants” (those from southern and eastern Europe). This created an environment ripe for the animosity Americans would direct at German immigrants and culture once the United States went to war.28 A more immediate catalyst for wartime anti-German feeling was the conduct of German soldiers and seamen. Their malevolent actions, first in Belgium, which Germany brutally invaded in 1914, and later in the North Atlantic, generated revulsion among millions of Americans, who regularly encountered horrific newspaper accounts about the murder of innocent civilians, especially women and children.29

Wartime antipathy grew toward all things German—whether immigrants, German-language books, or the facial hair of a Cleveland elevator operator forced to trim his mustache because it made him look like Kaiser Wilhelm—and the US government exacerbated it all by whipping up support for the war.30 Within weeks of Wilson’s April 1917 war speech, an executive order established the Committee on Public Information (CPI), which put in place a government propaganda apparatus. In addition to producing leaflets, newspaper and magazine ads, and short anti-German films demonizing the kaiser, the CPI sent thousands of “Four-Minute Men” to movie theaters across the country to energize support for the war through brief patriotic speeches encouraging “real Americans” to back the war effort. Policy makers believed it was essential to press the American people to do their part, and the government sought to rouse them. Such fabricated patriotism would ultimately flow into unsavory channels, polluting American society in a variety of ways.31

Eventually, wartime anti-Germanism would batter America’s classical-music community, which, since the mid-nineteenth century, had been overwhelmingly Germanic in character. Conductors and orchestral players were predominantly German, as was the repertoire American ensembles played. One heard the German language almost exclusively in orchestra rehearsals, and the largest number of key figures in the classical-music sphere—whether conductors, instrumentalists, singers, teachers, or orchestra builders—hailed from Germany. The way one contemporary described German-born conductor Theodore Thomas would have applied to most figures in America’s classical music world up until the First World War: He “associated with German musicians all his life,” met with them every day, and lived in “a German atmosphere.”32 The Germans, it was widely believed, represented the pinnacle of musical culture.33

Soon after the United States went to war, in the spring of 1917, the question of performing German compositions, especially works by the two Richards—Wagner and Strauss—engendered a fierce debate, which would roil both the classical-music community and the larger culture. Among performers, critics, and listeners, there were some—the musical universalists—who believed German music belonged to the entire world and should remain untouched by the war. Music, they argued, transcended the nasty provincialism the war had forced to the surface of American life, and they thought it perfectly reasonable for all music to be performed without restriction.

But the musical nationalists could not have disagreed more. Continuing to perform German music would be unseemly, particularly while battling a brutal foe. More than that, the nationalists were convinced that the very act of performing and listening to German music in wartime might, in some inexplicable way, make it more difficult to defeat Germany, though the logic of this conviction was never fully explored. Consequently, among the musical nationalists, who were more vocal than the universalists, strong support existed for sweeping the work of certain German composers from American opera houses and concert halls. To be sure, there were divisions among those who favored restricting German music, with a small number believing all German compositions should be banned, while others argued that only the music of living Germans should be forbidden. What united the musical nationalists, beyond their antagonism toward Germany, was an antipathy for the German language, which led them to try to silence certain compositions in which the German tongue would be heard. For the nationalists, the experience of hearing German compositions, particularly operas sung in German, aroused feelings of anxiety, pain, sorrow, and rage.

Further complicating the story, as the United States became more deeply involved in the war, one’s position on what was acceptable was liable to shift, which suggests a key point: One’s views on German music were shaped less by the war in general than by American involvement in the war, which brought home the conflict’s horror in a visceral and increasingly painful way. It was American belligerency that informed how people responded to German compositions.

Beyond the matter of what to do about German music, America’s animosity toward Germany and German culture would also affect the country’s attitude toward German musicians in the United States, who confronted a public increasingly unwilling to allow “enemy artists” to perform. Singers, instrumentalists, and conductors, along with the operatic and symphonic works they offered the American people, were swept up in the anti-German fever, which grew increasingly fiery as the country’s involvement in the war deepened. If German music engendered anxiety and anger, the presence of German musicians caused similar distress, for they were believed to harbor attitudes that imperiled the United States. Musicians with German backgrounds, particularly those who were not American citizens, were thought dangerous, a widely held sentiment that was also directed at the German saloon keeper, manual laborer, and school teacher.

But such sentiments would not begin to engulf the country until after America entered the war in April of 1917. Indeed, in January, just weeks before the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany, Wagner’s operas retained their allure, as the Metropolitan offered New Yorkers three iconic works—Lohengrin, Die Meistersinger, and Siegfried—sung by an array of mainly German artists. Not a single question was raised about the propriety of such performances.34

On January 31, 1917, the German government announced that it would commence a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships, belligerent and neutral (including passenger and merchant vessels), in a zone around the British Isles and off the coast of Europe.35 Although aware that its policy, which meant all American ships would now become targets of German submarines, would lead to American intervention, the German government was convinced this final effort to strangle Great Britain would lead to victory. And this, German policy makers believed, would be accomplished before the United States could bring its power to bear in Europe. The German gamble was not without merit, though it was one Germany would lose.36

On February 3, Woodrow Wilson announced that the United States would break diplomatic relations with Germany.37 That same day, Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Orchestra were playing a young people’s concert at Carnegie Hall, which, due to the diplomatic situation, began with “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the popular patriotic tune that was not yet the national anthem. The German-born maestro told the audience one of music’s chief duties was “to inspire patriotism,” after which he led a performance of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, a beloved piece by a nineteenth-century German.38

In March, German submarines sank several American merchant ships, leading Wilson to conclude that America’s honor and safety would be compromised if he failed to respond.39 Equally significant, Wilson now believed that to have a hand in shaping the peace settlement, the United States could no longer stand on the sidelines. Wilson and his cabinet decided the country would enter the war, making it the first time in American history the government would send soldiers to fight in Europe.

On April 6, 1917, four days after Wilson’s call for war, as he affixed his signature to the war declaration, the Metropolitan Opera was performing Wagner’s Parsifal as part of its annual Good Friday tradition. Three German singers graced a stellar cast, along with an Austrian, a Dutchman, and several Americans, all of whom were led by Bodanzky. As the press reported, the company had no intention of banning German opera during the remaining two weeks of the season, and Die Meistersinger and Tristan and Isolde would be heard over the next few days.40 According to Musical America, which noted the coincidence of playing Wagner on the day America went to war with Germany, Parsifal reflected “a very different spirit from that which inspires that nation to-day.” Readers were told that the iconic music drama captured the solemnity of the international situation. The work’s theme of “redemption through suffering” lent the moment greater importance than it would otherwise have had. The notion that German compositions possessed more insidious qualities had yet to take hold.41

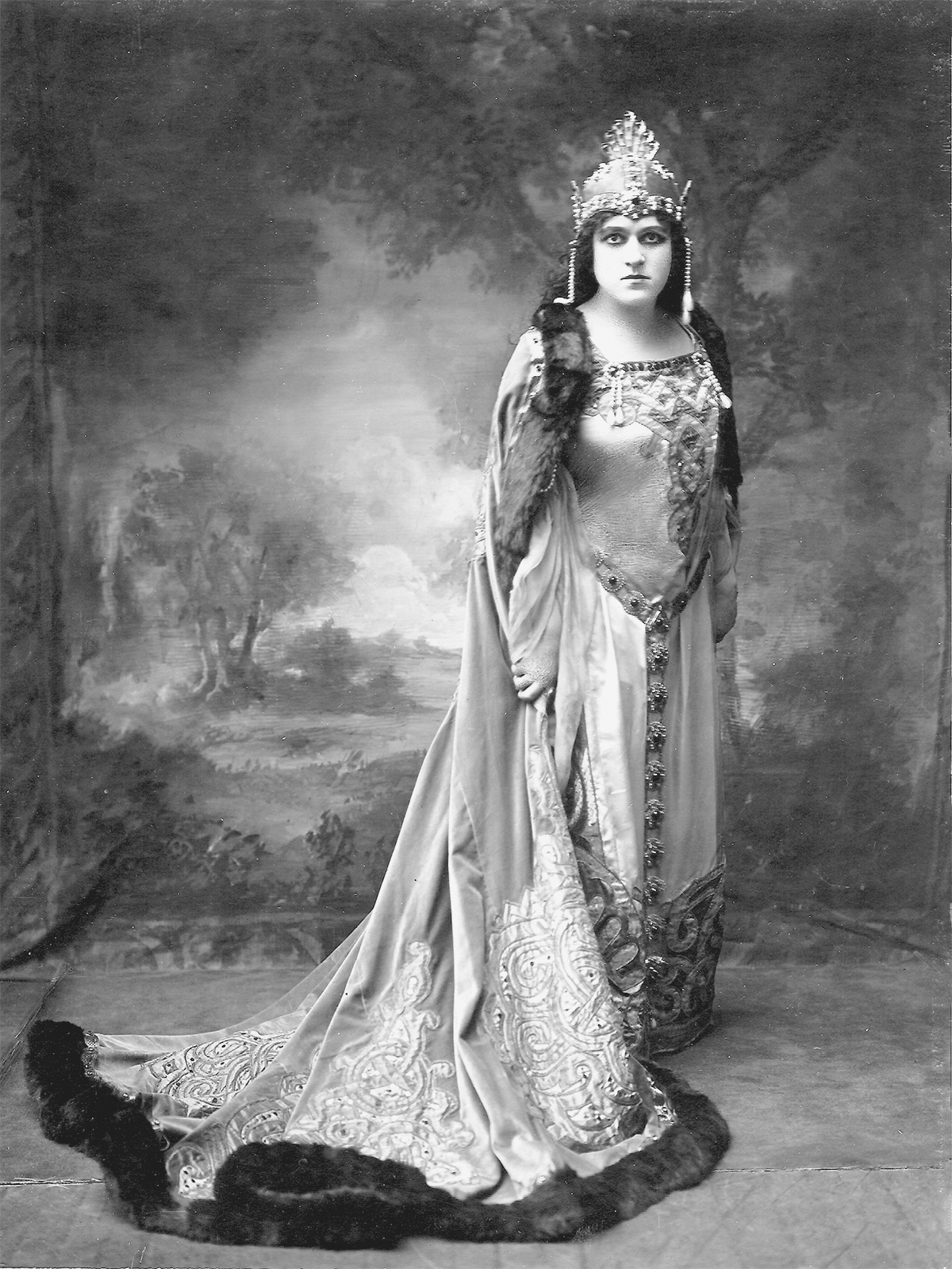

In mid-April, the Metropolitan Opera was the scene of dramatic developments, as some feared the audience would register its discontent toward German soprano Johanna Gadski, who was featured in the lead female role in Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. Gadski had been accused of questionable behavior, the result of a New Year’s Eve party she had hosted in 1915 in her New York apartment at which the well-known German baritone Otto Goritz had sung a virulently anti-American song making light of the killing of Americans at sea by German submarines. Gadski and Goritz claimed the song was simply an innocent example of New Year’s revelry with no anti-American subtext. More difficult to deny was that Gadski’s husband, Captain Hans Tauscher, a representative of the German munitions maker Krupps and a reserve officer in the German army, had been indicted and tried for conspiring to blow up Canada’s Welland Canal in 1916. Although Tauscher was acquitted and had left the country, some in the press thought the Met should terminate Gadski’s contract on the grounds of anti-American behavior and questionable associations.42

Yet, nothing untoward happened on that April evening, and the performance of Tristan was beautifully realized. Gadski sang exceptionally well and the audience demanded repeated curtain calls. According to one writer, it was a wonderful display of “the American sense of courtesy!”43

While widespread support persisted for the German singer, some continued to demand Gadski’s head. The New York Globe argued for removing her from the Met stage and published numerous letters on the subject, nearly all supporting its position.44 Animosity toward Gadski and other German artists also appeared in The Chronicle, a New York monthly, which declared that she, along with all supporters of the German government, should be fired. According to the paper, plenty of American singers could perform Wagner as well as Gadski, who saw “right in tyranny, brutality, and bestiality.” The publication highlighted the perniciousness of the German language, which led “one [to] prefer his German music expurgated of the spoken word—the guttural tongue which voiced the entire category of national crime.”45

A few weeks after Gadski’s triumph, she announced her resignation from the Met, a decision she said was necessitated by the campaign against her. The Prussian soprano defended her actions and spoke of her affection for America. Denying that she had said or done anything against the United States, Gadski called it her “second home.” The Musical Courier, one of the nation’s most distinguished music publications, observed that all “friends of art” will lament what had happened to the great Wagnerian.46 Gadski’s April 13, 1917, performance in Tristan was noteworthy not just because it marked her final performance at the Met. More significantly, German opera would not be heard at the house until 1920—and then only in English—and no German opera would be performed, in German, until the 1921–1922 season, three years after the end of the war.

As one listens to the national conversation both inside and outside the music community in early 1917, one recognizes that many thought it would be foolish to allow the war to intrude upon what was played. An April editorial in the Chicago Daily Tribune sought to distinguish between the German government, described as a “menace” to America, and “German genius,” which had provided “some of the most precious possessions of civilized life.” While strongly disapproving of Kaiser Wilhelm, the editors maintained it would be shortsighted for Americans to deprive themselves of Germany’s philosophers, poets, artists, and scientists. That would not weaken the enemy. It was essential, they insisted, for the United States to be worthy of its “ideals,” and to fight “without venom.”47

This idea, that the United States had to transcend its hatred of Germany and the German people, was expressed often in the classical-music community. Significantly, the notion was central to the ideals Woodrow Wilson regularly conveyed to the American people. While by 1917 there was little inclination to excuse the actions of Germany, one detects a willingness among many to establish a boundary between art and politics. In the spring of 1917, a Los Angeles letter writer, Charles Cadmon, implored the editors of Musical America to “admonish” readers about the dangers created by war’s “inflamed passions,” which might cause one to forget that it was crucial to continue to appreciate the superb “music and musicians of all nations.” Calling himself a “loyal American,” Cadmon promised he would keep his ideas about music and musicians distinct from his reflections on “patriotism.”48

If the dominant view suggested it would be foolhardy or even un-American to ban German music, one began to hear unsavory noises, which, ultimately, exerted considerable influence on American musical life. In a letter to the New York Times, Edward Mayerhoffer, despite being a German-born musician living in a New York suburb, said he understood why Americans might not want to hear German music. The “morals” of the German government and the German people have “proved to stand so low” that it was impossible to listen to such music these days without a great feeling of irritation. It might be wise to ban German music when played and directed by Germans, he observed, until the war was over.49 A similar perspective, expressed in Musical America, revealed growing discomfort at the prospect of hearing performances of German music, though the letter writer acknowledged that the “great composers belong to humanity and not to any particular nationality.” While recognizing the “genius” of Wagner, Beethoven, Brahms, and even Richard Strauss, he admitted that he found the “very word ‘German’ ” to be “offensive.” At one time, it represented a variety of noble qualities, but the war had altered his perceptions. For now, the writer would listen to no German music, as it reminded him of “scenes of horror” and of the “outraging of women.”50

By the fall of 1917, it was increasingly common to imagine that German music was inseparable from Germany’s repellent wartime behavior, which fueled the idea that it might become necessary to inoculate concertgoers from the threat presented by German composers. As an overseas correspondent for a New York paper remarked, once the word “Hun” became “the well-nigh universal description of a German,” Germany’s relationship with the world had changed.51 The conviction that Germans were barbarians, which intensified as the United States became more deeply involved in the war, would ultimately transform the bond between concertgoers and German music, thus undermining the belief that art transcended politics.

Wondering about the coming New York music season, the New York Herald asked whether German opera, songs, and concert music would lose their fascination. And what about artists from Germany and Austria-Hungary? Would they remain popular or would Americans replace them? If the public supported maintaining the status quo, the article claimed, the German masters of the past would be heard.52

As the 1917–1918 New York season began, all seemed in order in America’s most populous city, a metropolis with an enormous foreign population that included more than seven hundred thousand residents of German heritage. The Metropolitan Opera was poised to perform a full range of works, including nine operas by Wagner, while the opening concerts of the city’s two major orchestras, the Philharmonic and the Symphony, included pieces by the most prominent living German composer, Richard Strauss.53 The Herald reported that the public continued to respond to German music as enthusiastically as it did to French and Italian compositions. Audiences had embraced the notion that “art is international,” an idea Walter Damrosch addressed at the opening concert by his New York Symphony.54

Damrosch told the audience he had received a letter from an old and valued subscriber, asking whether the orchestra should now ban German music. After asserting that the United States had to do everything it could to achieve victory in a “righteous” cause, Damrosch explained why he intended to present the music of all nations. Giving voice to the universalist idea, the conductor spoke of music’s power to provide a balm for the scars wrought by war. The concerts would serve as a haven from war’s chaos and a “solace for its wounds.” The war was terrible, but the life of the country must go on. It was essential, he insisted, for organizations like his symphony to continue to receive support, “more whole-heartedly, more whole souledly,” in war than in peace.55

As for what music Americans should hear, the German-born conductor said it would be “ethically false” to allow our anger toward the German government to lead us to exclude the “German masters.” Banning the music of Bach or Beethoven or Brahms would be misguided. Such figures no longer belonged to any one country, but were part of the “artistic life of the entire civilized world.” Damrosch would accept no limits on the music he presented to the American people. Rather “would I lay down my baton than thus stifle my heart’s deepest convictions as a musician.”56

New York’s other leading ensemble, the Philharmonic, was hit hard by the war. The orchestra’s German-born president, Oswald Garrison Villard, was the grandson of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison on his mother’s side, which left him with a highly developed moral sensibility, a quality his mother helped foster. Oswald was also the son of Henry Villard, railroad magnate, financier, and a leading figure in the newspaper business. In the era of the Great War, this child of principle and privilege, who headed the New York Post and The Nation (both inherited from his father), was a committed pacifist.57

In his 1917 presidential address, Villard set the ensemble’s mission in the context of world politics by ruminating upon the experience of attending a Philharmonic concert:

[L]et no one forget that these walls a citadel of peace enclose. The pitiful waves of sound that beat across oceans moaning of bloody, unreasoning death pass by this temple of art. No echo of the strife without can enter, for here is sanctuary for all and perfect peace. . . . Herein meet citizens of one world to acclaim masters of every clime. . . . Democracy? Here is its truest home.58

For Villard, music could filter out the toxins of a diseased world, and the musician could still the unsavory passions that propelled world leaders and those that did their bidding. Such sentiments suggested that music was crucial to America’s well-being, especially in wartime. But Villard, who became an object of scorn among the musical nationalists, soon had reason to doubt such verities.

In early 1918, Villard resigned. While the reason for his decision is murky, it seems clear that his stance on the war led to his departure, though he said he had originally planned to serve for only a year. But Villard’s correspondence indicates that his opposition to American intervention in the war and his criticism of US diplomacy made his Philharmonic presidency untenable.59 In his January 2 resignation letter, Villard acknowledged that his view of the war was at odds with prevailing sentiment. A “hysterical” perspective dominated public opinion, he said, which made it necessary to act in a way that would not harm the Philharmonic.60

If Villard’s decision suggests how the war touched New York’s music community, the Philharmonic’s changing repertoire underscores how the struggle began to reconfigure the city’s musical culture, for the orchestra began and ended the 1917–1918 season with two strikingly different ideas about performing German music. At the Philharmonic’s opening concert in late October 1917, the ensemble offered the music of Richard Strauss, a German who was very much alive. While not every concertgoer was pleased, the rationale for playing German music is suggested in an exchange of letters between Thomas Elder, a former Philharmonic subscriber, and Felix Leifels, the orchestra’s manager and secretary. After receiving an angry letter from Elder, who reminded Leifels that he (Elder) had complained previously that many listeners found all-German programs unacceptable, Leifels responded forcefully. The “high art of music and musical genius is the property and privilege of the world.” It should not be linked to the crimes of a particular government. The United States was fighting against the ideas of the “Teutonic rulers and not against the great works of musical art wrought by men of genius,” who were not responsible for the conditions that had forced America into battle. Concerning Wagner, whom Elder had apparently singled out in an earlier letter, Leifels asserted that the composer’s views did not reflect the authoritarianism of the kaiser’s Germany. Indeed, Leifels explained, Wagner was exiled from Germany for a dozen years for participating in the 1849 revolution in Dresden against “autocracy.”61

While one cannot say how widespread Elder’s sentiments were, his views are deeply unsettling. Though not opposed to playing German music, he worried that those attending such performances, especially concerts devoted solely to German compositions, might not fully embrace the war effort. His cousins fighting in the trenches in France needed every bit of support they could get, he said, but “pacifists” might make it difficult for “our boys” to fight if they believed the home front was divided. Elder claimed he was prepared “to assist in the lynching of all such people.” Those opposed to the war did not yet understand that “patient people” would eventually take “things into their own hands.” While Elder said he found Wagner’s music appealing, he insisted that concerts comprising only German compositions could be morally destructive by elevating “things German before the public.”62

With the Philharmonic season underway, the disquiet over performing German music persisted. On a mid-December evening, with Stransky on the podium and the ensemble playing several Wagner excerpts, a message about the composer’s politics appeared in the program. It sought to allay the concerns of listeners inclined to link German music—Wagner, specifically—to Prussianism. The statement asserted that Wagner was a political and a musical revolutionary, and added that he had contemplated coming to the United States after the failed revolution of 1848, and gave “speeches and wrote articles in favor of freedom.”63 The Philharmonic’s effort to portray Wagner as an enlightened democrat was not unusual among those seeking to justify continuing to perform his music. Whether such history lessons influenced the outlook of concertgoers is difficult to gauge. More certain is that audiences continued to respond enthusiastically to Wagner, as they did on that winter evening, especially when his music was encountered in the concert hall—which usually meant they would not have to endure hearing the German language.64

On those occasions when singers graced the concert stage, listeners could now avoid the alien tongue. In mid-January 1918, the orchestra offered a successful Beethoven-Brahms festival and several days later, the Carnegie Hall audience heard Wagner in a Philharmonic concert attended by a number of American and Allied servicemen in uniform. The latter concert featured several arias from the Wagner canon—all sung in English—as was the case some ten days before in a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth, in which the text of the final movement was offered in translation.65

Despite what orchestra manager Leifels had declared a few months before, in late January, the Philharmonic stopped performing the music of living German composers. The first to go was Richard Strauss, whose Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks was stricken from two programs. In deciding that New York audiences would no longer hear compositions by living Germans, Leifels said the ensemble had been removing their works occasionally, and “we decided that we must hang our flag out once and for all.”66 An increasing number of protests from subscribers who opposed hearing some German music had led the board to act, though he emphasized no one had complained about playing the music of “dead Germans.” According to Leifels, the board recognized that patriotism was behind the protests, and he pointed out that the ban would apply mostly to the music of Richard Strauss, since almost no other works by living Germans were part of the orchestra’s repertoire.67 A supportive Maestro Stransky observed that the orchestra was merely doing what had been done in the other Allied nations. The programs for the current season had been planned before the country went to war, he said, with many concerts scheduled to include works by Strauss, when that was not yet a source of distress.68

Among the reasons for banning pieces by living Germans, aside from wishing to silence “alien music,” was the contention that playing Strauss meant American funds would flow into the hands of a German national via royalty payments, providing material comfort to the enemy. Whatever the justification, not every observer approved of the Philharmonic’s decision, as a Musical Courier piece suggested. After noting that the US government had recently ruled that German and Austrian royalty payments would henceforth be suspended—thus undercutting the economic argument—the publication labeled the Philharmonic’s policy absurd, adding that all it would take for the music of Strauss to return to the concert hall would be for him to expire. And there was a peculiar logic to the idea that the death of Strauss “would cloak him with virtue,” meaning his music would no longer reflect “the spirit of modern autocratic Germany.”69

Musical America responded differently. There was no cause for upset, the editors pointed out, since concertgoers would be deprived mainly of the music of Richard Strauss, which meant, sadly, no more Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel, or Death and Transfiguration. As for the other Germans whose music would be silenced, they were not crucial to the community’s “musical happiness.” After all, how much would anyone miss the temporary absence of Weingartner, Humperdinck, Korngold, and Schoenberg?70

As the Philharmonic season drew to a close in the spring of 1918, another storm swirled. At the April 1 annual meeting of the orchestra’s board it was made known that a letter had been sent to a board member by Richard Fletcher, editor of The Chronicle, the monthly notable for whipping up anti-German feeling, particularly about musical matters. At the time, Fletcher had been working closely with a second board member, Elizabeth (Lucie) Jay, who was similarly energetic in expressing anti-German sentiment (especially about classical music), and who had been laboring doggedly to limit what could be played and by whom. Fletcher’s letter asked for Josef Stransky’s resignation, appealing to what he believed was the inclination of all loyal citizens to remove the enemy stain from the national landscape. The time had come, Fletcher declared, “for every true American to stamp out whatever Teuton influence . . . remains in this country.” He informed the board that he had learned the maestro’s box had been visited by questionable characters whose allegiance to America was suspect.71

The board did not act on Fletcher’s letter and Lucie Jay resigned. The press reported that Stransky had begun the process of becoming an American citizen, and noted that he now called himself not an Austrian but a Czecho-Slav, which meant he was not necessarily an enemy of the United States. Meanwhile, a New York Tribune piece claimed that Stransky had told a reporter that he supported the president. But the allegations continued. It was rumored that Stransky had offered his services to Austria at the start of the war, a story he emphatically denied. Still more problematic was the publication of a photograph in several papers, which showed the conductor’s wife standing in the company of pro-German figures in New York, along with Count von Bernstorff, then the German ambassador to the United States.72

The day after the board had considered his firing, Stransky issued a long letter that appeared in various newspapers and periodicals, in which he attempted to establish his innocence and loyalty to his adopted country. In lawyerly fashion, the conductor presented the reasons concertgoers should support him. During the first part of the war, he acknowledged, his “sympathies were with the German people,” though he pointed out that he had never favored the policies of the German government. With America at war, Stransky declared, “I decided to take a definite stand with my adopted country.” The conductor highlighted his decision to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at numerous Philharmonic concerts, and spoke of his Bohemian (i.e., pro-Allied) origins and Czecho-Slovak parents. Stransky noted that he had taken out US citizenship papers, renounced his native country, and had been “outspoken for America.” He had donated his services to the Red Cross, given money to patriotic organizations, led his ensemble at army camps, and was responsible for the Philharmonic’s decision to ban all pieces by living Germans.73

Still, some were unwilling to let Stransky off the hook. With Fletcher in charge, The Chronicle continued to challenge Stransky’s loyalty, claiming it would not abandon the question until the conductor had explained the evidence against him. The editorial declared that he now “bleats of a belated and unconvincing loyalty to the United States.”74 Despite the effort to remove him, Stransky survived, and when the next season began, he remained on the podium, though many still doubted his loyalty.75

The city’s other leading ensemble, the New York Symphony, opened the 1917–1918 season under Walter Damrosch with a program that included the music of Richard Strauss. The German-born conductor spoke that day of his unwillingness to allow the war to limit what he would perform, meaning all German compositions would remain. But that would change, as Damrosch’s orchestra, like Stransky’s, would restrict its choices and proscribe compositions by living Germans, while Wagner would be limited to instrumental excerpts from the operas. Beyond that, any works that included the German language would be performed in English.

In an exchange with one of his subscribers in May 1918, Damrosch explained his position on playing German music, a view he also considered in his memoir published a few years after the war. Writing to Mrs. Lewis Cass Ledyard, who had contacted him to explain that she planned to resign her position on the orchestra’s board because of the continued performance of German compositions, Damrosch claimed that music should not be dragged through the ideological mud created by the war. While Germany had “strayed from paths of honor,” he wrote, the works of the iconic figures of German music—Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms—had become as much a “part of American civilization as of Germany’s.” Such personalities were not responsible for the execrable actions of the German government, he said, insisting they had nothing to do with the torpedoing of the Lusitania (the British passenger ship on which 1,198 innocent people had perished), or with the “Rape of Belgium.” He understood her desire to ban the music of living Germans, and the wish to eliminate “the German tongue from our operas and concerts” until Germany returned to its place among “civilized nations.” As he reminded Mrs. Ledyard, the British and French, who had endured far more wartime pain and suffering than the United States, continued to perform the music of Beethoven, Brahms, and the operas of Wagner (in English).76 There was little chance, Damrosch asserted in another letter, that the American people, upon hearing a Beethoven symphony, would believe that a country capable of producing such wondrous music was not also capable of committing the “atrocities” of the current war. America’s cause was sufficiently strong that playing German compositions would actually highlight the difference between the nobility of such music and the low state to which present-day Germany had fallen.77

Nor was the debate in New York limited to the symphonic realm, for the Metropolitan Opera Company faced challenges of its own. Given the importance of German opera in the company’s repertoire, it is no surprise that tensions flared during the first full operatic season after America went to war. As the 1917–1918 season began, Lucie Jay, the only woman on the Philharmonic’s board, launched an attack against the Met. In The Chronicle, she offered the first of many contributions on German music, which, when compared to her later efforts, was a measured response to the Wagner question. A note appended to the article alerted readers to The Chronicle’s position, with the editor asserting that Jay was boldly firing “the first shot against the menace of this insidious German propaganda.” According to the editor, the genius of many German figures, including Beethoven, Goethe, and Bach, had long been used to advance the “Teutonic plan for world dominion.” The point was clear: German opera should be banned until the war was over.78

Lucie Jay pleaded for a deeper relationship between classical music and the American people, and hoped the public might develop a richer musical understanding, which went beyond responding to the “emotional in music,” by which she meant an attachment to late nineteenth-century compositions like those by Tchaikovsky and Wagner. Music lovers ought to explore and appreciate the music of Bach, Mozart, and Haydn, which would enhance their artistic sophistication. She repudiated those who supported a complete ban on German music. Nothing inherent in German concert music necessitated its elimination, she wrote.79 It would be a “mistake,” however, to perform German opera during the war, especially Wagner. Particularly when sung in German, Wagner’s creations depicted violent scenes, which would ineluctably draw the minds of Americans to the “spirit of greed and barbarism,” which had produced so much suffering.80

Apart from Jay’s ruminations, one could encounter more-compelling reflections on German opera, as suggested by the heartfelt declaration of a mother of two soldiers fighting in France. This longtime Met subscriber said she understood the argument that “masters” like Wagner and Beethoven did not represent current “German ambition and German thought,” and she realized her resentment toward Germany should not include hostility toward German opera performed by German singers. She confessed, however, if “I and others who are in the same position are to be honest . . . we cannot listen to anything which suggests the horror that we mothers now face.” The source of her distress lay in the “very word ‘German’,” which “conjures up in our minds” an “intolerable” situation.81

One can empathize with this mother of two doughboys and understand the pain she experienced at a performance by someone such as Otto Goritz, who had allegedly exulted in German atrocities like the Lusitania sinking, which killed nearly 1,200 souls, including 128 Americans. But her distress sprang from something deeper than the transgressions of a callous singer. The source of her anguish, she suggested, lay in German culture—or even German-ness. And such emotions, unleashed by listening to German artists singing German music, meant that hearing German opera had become impossibly difficult. A personal connection to the war, a consequence of having family members under fire, explains why some could not disentangle German music from events overseas.

That same autumn, The Nation offered a different perspective on Wagner, in particular, arguing that banning his music would be “stupid.” Assessing the coming season at the Met, the editors observed that Wagner would be adequately represented, which was as it should be. There was no reason “to taboo Wagner” because the United States was fighting “Prussian militarism.” The editors pointed, as had others, to Wagner’s position as a stern critic of Germany. Were he alive today, he would be leading the reaction against “Kaiserism,” and they were relieved that his music remained on the Metropolitan’s list for the coming season.82 This position was embraced by various publications and individuals whose opinions were reflected on editorial pages and in readers’ letters.

Although the Met had planned to present Wagner in the 1917–1918 season, on November 2, the company announced that German opera would not be performed at all.83 In his memoirs, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the company’s long-time general manager, described the cancellation as his gravest challenge. Before the season began, the Italian administrator had been told, “You must continue to present German opera.” But in October, when “the war had really begun for this country,” and reports of the wounded and the dead began to reach America’s shores, members of the Met’s board said maintaining the German repertoire would be impossible.84 Once the bloodletting touched the American people, German opera was swept from the stage.

As Gatti-Casazza would observe years later, he had suspected this would happen, which had led him to prepare a different set of performances that included no German works. When the Met’s board decided in early November that German opera would be banned, French and Italian compositions, along with some American and English operas, were substituted, a change the Met implemented within a week’s time. The general manager claimed the revised calendar was highly successful, and he recalled that twenty-three weeks of performances were presented, minus the forty to forty-five performances of works in German.85 Gatti-Casazza made clear that he had nothing to do with the ruling; his task was merely to implement the board’s wishes. As he told the Musical Courier, “Personally I have held that reason and fairness should rule in these matters, but . . . at a time like this, emotion is a much stronger force.”86

As for the board’s action, it was reported that there was internal disagreement among the directors, with a New York Herald story explaining that a small minority favored continuing to offer the German repertoire. Apparently, the eruption of Karl Muck’s problems with the Boston Symphony (to be discussed in the next chapter) had a significant impact on the Met’s decision. The Herald also claimed that the board, which was entirely male, had been pressured by a group of society women who wanted to ban all German opera in New York. If nothing else, the company’s management feared that on the nights Wagner was offered, typically once a week, the ring of expensive parterre boxes, known as the “Diamond Horseshoe,” would remain vacant. While it was not initially clear whether German opera would continue to be performed in English, soon all German opera, whatever the language, would disappear.87

In the wake of the Met’s decision, debate ensued among music commentators and the public about the alleged perils that performing German music, especially Wagner, posed to American society. As the Musical Courier explained, offering Wagner as before, with German artists singing in German at the nation’s largest opera house, would allow the German government to claim the United States was “not heart and soul in the war.” The solution was to have Wagner on American terms—with American conductors and American singers performing in English. Wagner’s creations were “world music,” which belonged to all.88

Less enlightened publications had little sympathy for those who continued to support performing German opera. According to The Chronicle, those opposed to the ban were a “crop of idiots.” By rejecting proscription, such “fools” were aiding the “German Cause,” even if unconsciously. Indeed, such open-mindedness reminded one of the pacifists’ outlook, The Chronicle acidly remarked, a group Woodrow Wilson had dismissed on account of its “stupidity.”89

Members of the public weighed in, their letters ranging from simplistic to thoughtful. Writing to the New York Times, Marian Stoutenburgh observed, if German opera had continued, German singers would have been retained to perform Wagner, which led her to wonder “what loyal American would want to listen to a group of men and women,” who, if they had the chance, would do all they could to aid the enemy? According to this New Yorker, everyone understood that “great art belong[ed] to the civilized world,” though it was a “shame” to have it performed by those whose “zeal for the Fatherland” was clear.90 Other Times readers shared more incendiary reflections, emphasizing music’s malign power. “Our sons and husbands are hourly giving their lives to save America and civilization from the onrushing devastation of the loathsome Prussian war monster,” Myra Maxwell declared. At this moment, would even the “most rabid adherents of German opera” be willing to endure the “unlovely guttural language of our enemy, hissed in their faces under the friendly guise of art?” Scoffing at those who spoke about the “universality of art,” she said there would be ample time to consider such things when the war was over. For now, America should concern itself with “German arms . . . not German art.”91

But not everyone favored banning German opera. In numerous letters to the editor, an idealistic contingent eloquently repudiated the anti-Wagner clamor. A few days before the ban was announced, a New York Tribune letter writer from Princeton suggested it was essential to “keep our minds in a sound . . . condition.” This was not the moment to heed the words of the “Hysterical Patriot.” Wagner, this reader pointed out, provided pleasure to countless listeners, and during these gloomy times his music should be permitted to offer “solace to those who love him.”92 Another letter to the Tribune pointed to the universal character of music, which “knows no race or creed.” In terse prose this anonymous correspondent asserted, “I am not defending German principles, but I am defending art.”93 Reacting to the Met’s decision, an Ernest Skinner wondered what Wagner’s music had to do with the war. Wagner belonged to the entire world, he averred. “Wagner is dead. . . . His music lives: it has not . . . sunk any ships.”94

Others were far less enlightened. Several months after the Met’s decision, author and journalist Cleveland Moffett considered the subject of German music in The Chronicle, his prose dripping with hatred. The music should be driven from America’s “homes, churches, theaters, concert halls, [and] opera houses.” This was necessary to honor the “millions of dear and heroic ones,” who had died or would yet die, who had been mutilated or would be, who had been bereaved or would soon be, as a result of “Germany’s unspeakable wickedness.” German musicians spoke with the soul of their country, Moffett asserted, a soul responsible for ravishing Belgium and sinking the Lusitania. Their music threatened America. He asked: “Am I preaching hatred of Germany? Yes—for the present!” It was essential. “We must hate the Germans, just as we must use poison gas against them, and bombard their cities.”95

Across the country, discomfort and outrage bubbled up over the performance of German music. Worse still, rising antipathy flared toward German-speaking musicians. The German question caused a stir in the musical life of Chicago, which was not surprising, given the city’s large German population; the history of its orchestra; and the heritage of Frederick Stock, the Chicago Symphony’s conductor. In 1900, one in four Chicagoans had either been born in Germany or had a parent born there. By 1920, the proportion of those who acknowledged having a German background had dropped slightly to 22 percent, but the city, with a metropolitan area inhabited by more than three million people, had the second-largest German population in the country after New York. The rising tide of anti-German sentiment that swept over wartime Chicago was clear, as evidenced by two name changes: The Bismarck Hotel became the Hotel Randolph and another lodging, the Kaiserhop, became the Atlantic.96

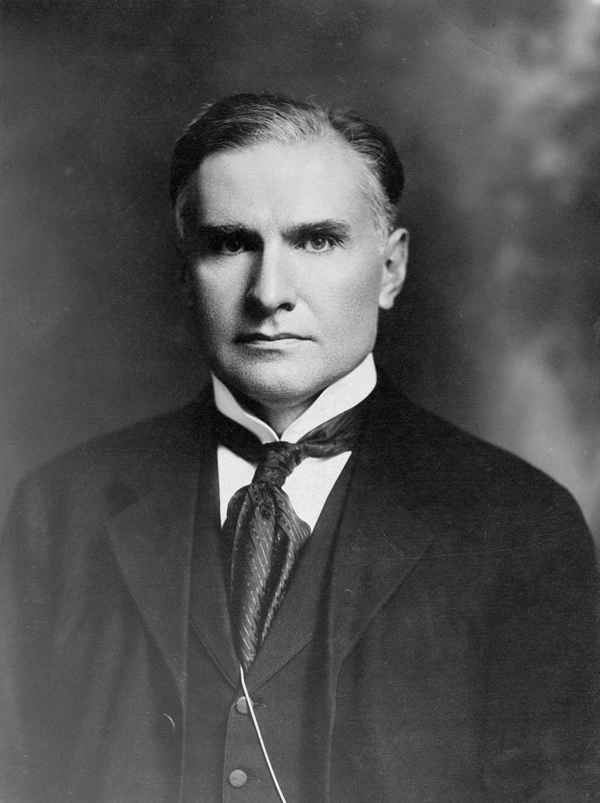

Born in Germany in 1872, Frederick Stock began studying the violin with his father, an army bandmaster. At fourteen, Stock enrolled at the conservatory in Cologne, where he worked with the composer Engelbert Humperdinck. Upon graduating, he joined the orchestra in that city, playing under an array of legendary figures, including Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Richard Strauss. In this period, Stock encountered conductor Theodore Thomas, who invited him to come to the United States to join the string section of his ensemble in Chicago, which had been formed in 1891. When Thomas died in 1905, Stock was appointed conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, which would soon become one of the finest symphonic organizations in the country.97

Concluding its season in late April 1917, less than three weeks after Woodrow Wilson had asked Congress for a declaration of war, the orchestra offered an all-German affair of Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, and Richard Strauss, whose Till Eulenspiegel was played, one reviewer noted, with the requisite “rollicking fun and absurd humor.” According to one report, an enormous American flag covered the back of the stage, and the evening ended with a lusty rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” during which Stock turned to direct the audience from the podium, a German leading a throng of patriotic Americans. The only fly in the ointment that night was the behavior of three boys, described as “dreamers” and “pacifists,” who refused to stand during the performance of the patriotic tune, which led to their arrest and landed them in jail and then court, where they had to explain their actions, including the charge that they had made insulting remarks about the flag.98

But Chicago’s musical life faced greater travails than the dubious behavior of three dreamy adolescents. In the first month of the war, the maestro described how the men of his orchestra, 60 percent of whom were of German descent, were doing their best to keep their wits about them. While several German musicians had complained to Stock that they were being heckled, the conductor said the situation was to be expected. None had spoken of resigning, and all were loyal to the organization and to the United States, he said. Arguments about the war were not permitted in rehearsal, and if his players were inclined to discuss the conflict outside the concert hall, nothing could be done about it. And most important, he noted, the orchestra was “working better than ever.”99

This situation would prove difficult to maintain. In early 1918, Stock’s name appeared on a list of enemy aliens, the result of his failure to complete his citizenship papers, a process he had begun years before. As such, he was now prohibited from filing for citizenship. Consequently, Stock would remain an enemy alien until the war’s end.100 In April, the press reported that the Department of Justice would investigate stories claiming the conductor was “pro-German.” But the report proved inaccurate and no investigation occurred. Indeed, those connected to the orchestra offered ample testimony concerning Stock’s loyalty. It was generally agreed that he was unfailingly faithful to the United States, and the furor over his status dissipated.101

The tranquility would be short-lived, however. In August, the Chicago Federation of Musicians, the local union, decided to expel all subjects of the kaiser, including enemy aliens. As union musicians could not play for more than two weeks under a nonunion conductor, and since Stock, as an alien, would no longer be a member of the union, his position as head of the symphony appeared precarious.102 Almost immediately, however, the union rescinded its initial position so that any member whose loyalty was compromised, regardless of citizenship status, could be subject to legal action. In theory, this change meant someone like Stock was not necessarily liable to dismissal, so long as he had done nothing that raised questions about his loyalty to the United States.103

While there was little concern about Stock’s loyalty, as Musical America pointed out, it was necessary in wartime to err on the side of caution. Most people thought Stock was the right kind of German, who bore no “secret grudge” against the United States. Nevertheless, while Stock had never uttered a harsh word against America, from the journal’s perspective, dangerous times made it essential to examine closely “the spirit” and “the letter of a man’s patriotism.”104 But Stock had his supporters. According to the Chicago Tribune, “He has carried himself . . . with poise [and] restraint,” and was completely devoted to the United States.105

Despite this support, on August 17, 1918, for the sake of the orchestra, the maestro submitted his resignation. The conductor spoke of his years of devotion to the ensemble, and to the United States and its values. He had come to America not merely to make a living, but because he believed its “air of freedom, buoyancy, and generosity” would allow his spirit to breathe and his art to evolve. As a youth in Germany, he had rejected autocratic government and worked against a “growing spirit of militarism.” He now felt the United States was his native land. Even before America went to war, Stock noted, he had declared that Germany was in the wrong and must be defeated. This belief had become a profound conviction, and one for which he was “as willing as any patriot” to give his “last drop of blood.”106

The trustees responded, expressing appreciation for Stock’s “noble motives” and acknowledging his loyalty to the United States. They noted that Stock had changed the language of symphony rehearsals from German to English and had regularly led all-American programs. After accepting his resignation, the trustees told the conductor that they anticipated welcoming “Citizen Stock” back to the podium after the war.107

The maestro was not the only musician associated with Chicago’s orchestra to come under scrutiny. In the summer of 1918, questions intensified regarding the loyalty of a number of musicians, of German heritage, whose actions had caused concern. Seven players were hauled into the office of the assistant district attorney as a result of allegations brought to federal authorities by two “loyal” members of the orchestra. As the assistant district attorney observed, “if they engage in un-American words or acts, they will have to explain” themselves.108 According to press reports, the problem stemmed partly from the musicians’ “pro-Hun utterances,” including one player who had supposedly remarked, if Germany lost the war, he would kill himself.109

A complaint was also lodged against cellist Bruno Steindel, who, during an orchestral performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” allegedly replaced the standard lyrics with an obscene version of his own devising. A naturalized American who had emigrated from Germany in 1891, Steindel attracted the authorities’ attention, though he denied and tried to justify his behavior in light of the accusations leveled against him. It was said that Steindel had declared that Woodrow Wilson was working on behalf of England, and had claimed, if “not for the American dollar America could go to hell.” Queried about a performance of “The Marseillaise,” during which he had remained seated, Steindel suggested he had not been asked to rise. “Was it necessary that you should be asked?” the investigator wondered. Steindel said he was unsure what was expected, adding, “Besides, I could not stand and continue to play my cello.”110 Such was the level of discourse in wartime America, as accusations and explanations flew back and forth about why a distinguished cellist who had once played under Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Strauss had remained in his chair during the French national anthem. Was the explanation, as Steindel insisted, simply that one could not play the cello while standing?

Chicago Symphony Orchestra conductor Frederick Stock (standing) and cellist Bruno Steindel (third from left, with mustache).

In late August 1918, the symphony’s trustees responded to a Department of Justice inquiry concerning the allegiance of the orchestra’s players by adopting a series of resolutions pledging that the orchestra would ferret out disloyal members, which, it was hoped, would end the malign “gossip” that had swirled around some of the musicians.111 Praising the trustees’ action, the Chicago Tribune noted their good character guaranteed that no “disloyalist” would be permitted to remain in the ensemble once his actions were exposed.112

To make sure no orchestral musicians strayed, the orchestra manager spoke with the members of the ensemble, telling them he believed they were all loyal to the United States. Issuing a set of “don’ts” for his players, he declared: “Don’t use the German language in any public place. Don’t make thoughtless remarks. . . . Don’t forget it is every man’s duty to be loyal to America.” And don’t forget that management would report any member who showed the slightest sign of disloyalty. Concluding, the manager proclaimed, “We are all American citizens and are going to do what we can to help America and her allies win the war.”113

In October, Bruno Steindel, an American citizen and a member of the ensemble for more than a quarter century, was dismissed by the orchestra. According to the Tribune, the government had determined that his words had been “at variance with American ideas and the win-the-war spirit.”114 Musical America asserted that he was “distinctly disloyal,” the sort who lived in the United States and, whether citizens or not, had never “been Americans.” Such people had always been “ ‘Germans in America.’ ”115 That same month, an oboist, bassoonist, and trombonist, all with German surnames, were expelled for their alleged anti-American remarks.116

Elsewhere in the Midwest, the war was reshaping the contours of musical life. In Minneapolis, the symphony was directed by Emil Oberhoffer, a Munich-born maestro, who came to the United States at seventeen, becoming an American citizen soon after. Since 1903, the year the Minneapolis Symphony was founded, Oberhoffer had led the ensemble, which began each program during the war with “The Star-Spangled Banner” and concluded every wartime concert with “America.” Despite Oberhoffer’s German heritage, it was said that his south German background led him to abhor “Prussianism.” At Oberhoffer’s insistence, the language of the orchestra, in rehearsal, backstage, and in public settings, was English. And with the start of the 1918–1919 season, management required all members of the ensemble to sign an oath, which declared they would “pledge unswerving loyalty to the United States” and do all they could to help the government achieve “a complete victory.” The men of the orchestra also bought $20,000 worth of war bonds.117

In the spring of 1918, Oberhoffer sat down with a reporter to discuss his background, outlook, and views on music in wartime. Asked whether he was thought of as a German, Oberhoffer said, “Perhaps I am, as we are inclined to believe that only English, Scotch, and Irish names are American, but persons with names of other nationalities are Americans, too.” Sharing a personal anecdote, he recalled an exchange after a performance in Madison, Wisconsin, when a professor offered congratulations in German. Oberhoffer spoke of his distress, and his decision to reply in English, while his interlocutor attempted to continue the conversation in German. “I had to ask him to kindly speak in English,” the conductor said, adding that he no longer accepted social invitations, since he might unwittingly “make a faux pas by calling . . . on a pro-German.” Asked if he had any “alien enemies” in his orchestra, Oberhoffer indicated that some of the men, despite living in the United States for many years, had only taken out preliminary papers. That was not forgetfulness, he said. “One does not forget to swear allegiance to a country if one really desires to be a citizen of that country. . . . [A]s soon as I found out the United States was a good enough place for me,” he declared, “I made up my mind to be a citizen.”118

The conversation turned to “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Asked if it was true that he had conducted the piece long before the United States went to war, Oberhoffer said that he had, noting the tune should be sung and played. The words are crucial, he observed, declaring, he wanted audiences to understand that singing the piece was a “sacred function.” Nor should it be followed by applause.119

Two thousand miles to the west, the war impinged on classical music in Los Angeles in ways large and small. Though it would not have a full-time symphony orchestra until 1919, there was still much talk about the place of German music in the California city, which possessed a lively classical music scene.120 In January 1918, several influential guests at a swanky Pasadena hotel walked out of the establishment’s evening orchestral concert upon learning German compositions would be played. The episode, in which Weber’s Invitation to the Dance was on the program, led to a movement among some California hotel owners to remove German music from concert programs in Los Angeles and San Francisco hotels. Spearheading the ban was hotelier D. M. Linnard, who said he aimed to proscribe German music for the rest of the war.121 Also weighing in was Leslie M. Shaw, a former Treasury secretary, who was among those who had left the Pasadena concert. Worried about the influence of German music in wartime, Shaw asserted, this was no time for “internationalism in art.”122 A like-minded Californian told the Los Angeles Times that no one should doubt the danger posed by German music. As it lulled Americans to sleep, “Prussian militarism [might] stalk rampant over us.”123

In looking through the Los Angeles press, one sees that anti-German sentiment was rife across the city. In early 1918, the Times reported that a local piano teacher decided to remove German music from her students’ recitals.124 In June, the board of education withdrew three thousand copies of the Elementary Song Book from the city’s schools, when it was discovered that nineteen of its sixty songs were of German origin. The volume had been compiled by Kathryn Stone, the supervisor of music, who was upset about the fate of her book and about accusations of having German parentage. After perusing the work, the school superintendent ordered all three thousand copies destroyed.125

Defending the ban, the Los Angeles Times argued that a nation’s music and literature expressed its “ideals.” This was no time to cultivate in youngsters an appreciation for German compositions, which had contributed to “discord in the harmony of the world.” German music, the editors claimed, was the music of “conquest, the music of the storm, of disorder and devastation.” It combined “the howl of the cave man and the roaring of north winds.”126