“I Want to Teach a Lesson to Those Ill-Bred Nazis”

Toscanini, Furtwängler, and Hitler

ON APRIL 1, 1933, a group of distinguished figures from the American classical-music community cabled Adolf Hitler, asking his government to stop persecuting musicians in Nazi Germany. Distressed at the harsh treatment of artists like conductors Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, and Fritz Busch, the New York Philharmonic’s Arturo Toscanini and ten leading musicians petitioned Hitler in a highly public initiative, which attracted considerable coverage across the United States. In addition to Toscanini’s signature, the cable, brief and respectful, was signed by several conductors, a pianist, two composers, and a music educator:

The undersigned artists who live, and execute their art, in the United States of America feel the moral obligation to appeal to your excellency to put a stop to the persecution of their colleagues in Germany, for political or religious reasons. We beg you to consider that the artist all over the world is estimated for his talent alone and not for his national or religious convictions.

We are convinced that such persecutions as take place in Germany at present are not based on your instructions, and that it cannot possibly be your desire to damage the high cultural esteem Germany, until now, has been enjoying in the eyes of the whole civilized world.

The following day, newspapers across the country informed readers of the cable’s contents, which made clear the link between art and politics.1

That afternoon, the New York Philharmonic took the stage at Carnegie Hall to perform an especially fitting program. Led by Toscanini, the concert, which was part of a Beethoven cycle offered by the orchestra and its esteemed conductor, included the Eroica, a piece that was richly symbolic at this particular moment. In the program notes, the audience encountered the oft-told tale of Beethoven’s having torn the title page, inscribed with the name Bonaparte, from the original score. Raging against the man who had proclaimed himself emperor, the composer was said to have declared, “Then he, too, is only an ordinary human being! Now we shall see him trample on the rights of men to gratify his own ambitions; he will exalt himself above everyone and become a tyrant!”2 In hearing the Beethoven Third Symphony that afternoon, the audience surely perceived a convergence between music and the wider world, in a performance the New York Times described as so remarkable that even the composer could not have conceived of it. The concert allowed one to experience both “joy and tragedy,” which reminded listeners that “mankind need not be submerged in . . . hatred.”3

The audience appreciated the magnificence of what they had heard and was no doubt moved by the confluence of listening to this piece led by this conductor on this day. Beyond responding feverishly to the Eroica’s thrilling conclusion, the audience had given the maestro a sustained ovation as he walked onto the stage to begin the concert with Beethoven’s Fourth. The Times reviewer surmised that the response signaled approval of the conductor’s lead role in the cable to Hitler, an account of which had appeared in the newspaper that morning.4 In the days after the cable was published, each time the Italian musician strode onto the stage, the demonstration far exceeded the applause he usually received.5

• • •

With the end of the 1920s and the start of the new decade, the attention of the American people was trained on domestic matters, as the country moved from an era of economic prosperity and a rising standard of living, to a period of tumbling stocks, economic contraction, and widespread hardship. Because of the Great Depression of the 1930s, for much of the decade, overseas developments were not terribly important to most Americans. They were concerned, instead, with the day-to-day struggle for economic survival. For millions, unemployment, homelessness, and malnutrition were a greater foe than any dictator.

Despite the insular character of American life, the classical-music landscape was tightly bound to the European upheavals that flared in the 1930s, especially in Germany. This was due, in part, to the fact that leading performers continued to have one foot in Europe and one in the United States, and because America’s concertgoers remained drawn to German symphonic and operatic fare. Moreover, the increasing persecution of Jewish musicians in Germany did not just capture the attention of performers in the United States. While America’s musical community was distressed over the plight of artists in Europe, Germany’s brutal policies also attracted widespread coverage in the American press—in the arts and news sections—which deepened the American people’s understanding of the malign character of Hitler’s regime.

Beyond the cascade of press reports on Nazi persecution, the well-documented activities of two giants of the podium, Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler, also contributed to America’s growing awareness of fascism. From his perch in New York, Toscanini assumed a heroic stance by forcefully opposing the malevolent policies of Mussolini and Hitler, sometimes at considerable personal risk. And when the Italian conductor stepped down from his New York position in 1936, Furtwängler, Europe’s preeminent conductor, was appointed to replace him, a decision that erupted in a furious and highly public controversy, which again highlighted the debate between the musical nationalists and the musical universalists. Moreover, the tension between these celebrated maestros, which was widely publicized, served as a metaphor for what many saw as the stark contrast between America’s democratic ideals, embodied by Toscanini, and Nazism’s moral bankruptcy, as represented by Furtwängler. Yet again, the classical-music community was entangled in the web of world politics.

Although most Americans were unconcerned about the wider world in these years, a sense of unease did emerge over the rise of foreign dictators. If those pondering European politics in the 1920s and early 1930s initially saw Benito Mussolini’s autocratic rule in Italy in positive terms,6 once Hitler came to power in 1933, distress began to simmer in the United States. Still, most Americans were content to gaze upon the boiling European cauldron, and as late as September 1939, when the war in Europe began, America remained aloof.7

Despite their unwillingness to act assertively during the 1930s, Americans heard frequently about repression in the Third Reich, and learned that conditions in Germany, especially for Jews, were increasingly grim. Reports documenting anti-Jewish policies appeared in newspapers throughout the country, though Americans often responded with incredulity or indifference to stories about German atrocities.8

Within weeks of Hitler’s accession to power on January 30, 1933, stories began to appear in newspapers and the music press documenting the German government’s increasingly repressive artistic policies. As Hitler’s regime started to crack down on “undesirable” musicians and intrude into the affairs of German musical organizations, American readers could follow the sinister tale in considerable detail.9 They learned that men described as representatives of the Nazi Party had forced conductor Fritz Busch to surrender his position as director of the Dresden Opera. The same group shouted “Out with Busch” as he tried to begin a performance of Rigoletto. While Busch had supporters, the eminent musician would be chased from the post he had held since 1922. Known to New York audiences after guest appearances with the New York Symphony, Busch, though not Jewish, was accused, Americans learned, of having excessive social contact with Jews and of hiring too many Jewish artists. Moreover, his younger brother Adolf, a renowned violinist, had married a Jew and left Germany for Switzerland a few years before.10

In the early days of 1933, stories appeared in the United States about the celebration in Germany commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Wagner’s death. At Bayreuth, the summer festival devoted to the music of Wagner, the composer’s family opened an archive of letters, scores, and articles from his life to be made available to scholars. In Berlin, conductor Otto Klemperer, who would soon have to leave the country, led an innovative staging of Tannhäuser, which caused an uproar among Wagnerians for allegedly desecrating the creator’s memory. Americans also read about the illustrious crowd that had gathered at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig to hear a concert of the icon’s music, which was performed before Chancellor Hitler and members of his cabinet. The performance included excerpts from Parsifal and Die Meistersinger and was led by a man familiar to many Americans, Karl Muck, who could be found most days conducting in Hamburg.11

As Americans pondered this homage to Wagner, readers of Musical America encountered a March 10 editorial calling for tolerance in Germany, especially toward Jewish musicians. With Hitler just weeks into his chancellorship, the publication lamented that his regime had dragged music “violently into the area of political passions.” Pointing to the German leader’s love of Wagner—he was supposedly happier at a performance of Die Meistersinger than anywhere else—the editors called for the Nazi chief to show the humanity of Hans Sachs, a character from his favorite opera.12

That there was little tolerance in Hitler’s Germany, including in the creative sphere, was a reality Americans frequently confronted. Beyond this, as the decade unfolded, Germany’s brutal policies began to shape cultural life in the United States as an extraordinary group of classical musicians streamed across the Atlantic in an exodus that would vitalize the musical landscape for years to come.13 Illustrating the point, in early 1933, two distinguished artists, Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer, both of whom would one day reside in the conductors’ pantheon, felt compelled to leave Germany. They would ultimately land in the United States. The plight of Walter, Jewish and Berlin-born, who would settle in Southern California, became well-known in America, as did the plaudits he received after leading performances in Vienna and London. In March, Walter’s German career came to an abrupt end when he was prevented from conducting in Leipzig, Berlin, and Frankfurt. Headlines were splashed across American papers from coast to coast, forcing Americans to contemplate the musician’s fate under a regime that had placed a chokehold on his professional life.14

Thus, as early as 1933, the American public heard repeatedly about the grim transformation that was reshaping German musical life, as Hitler’s gang began implementing the anti-Jewish policies that would become increasingly sinister. The press trumpeted the growing horror, which became part of the nation’s cultural and political discourse. The saga of Otto Klemperer exemplified the fate of artists who had left Germany. As the American public would learn, even someone who was born Jewish and had converted to Catholicism years before could be barred from working as a musician.15 Leaving for the security of Switzerland in April 1933, Klemperer eventually reached the United States, where he would become the conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.16

That same year, German political developments began to resonate powerfully in the United States, as Toscanini severed ties with the Bayreuth Festival. Covered widely across the country, the Toscanini affair highlighted the insidious link between art and politics in Germany, compelling Americans to consider the threat Nazism posed to humane values.

By the time Toscanini decided he would not perform at Bayreuth in 1933, he had been a leading figure on the international music scene for more than a generation, and his position as conductor of the New York Philharmonic made him one of the most esteemed maestros in the United States. Blessed with prodigious musical gifts, Toscanini was famed for the “fanatical” precision of his interpretations of the operatic and symphonic literature and his unyielding fidelity to the score.17 Clichés notwithstanding, he was born into humble circumstances in Parma, Italy, in 1867, and before age twenty he began a meteoric rise through the professional ranks after important figures on the Italian operatic scene recognized the extraordinary ability that would one day captivate musicians and audiences throughout the world. Having worked as a cellist and conductor in Italian opera houses, where his skill with the baton became legendary, Toscanini made his New York debut conducting Aïda at the Metropolitan in 1908, a performance critics received enthusiastically.18

In time, Toscanini would also distinguish himself in the symphonic world, offering celebrated readings of Beethoven, Brahms, and Strauss, along with the works of many others. Assessing his 1926 debut with the New York Philharmonic, the first time he led an American symphony orchestra, Olin Downes of the Times wrote that Toscanini “worked his sovereign will” in unforgettable fashion.19

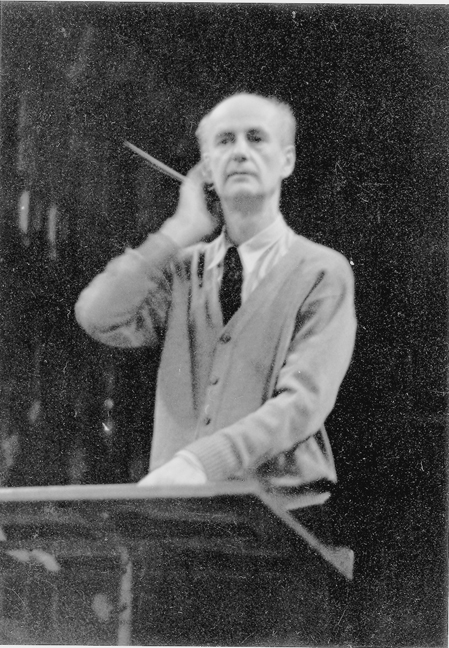

Arturo Toscanini

Enormously demanding, Toscanini was nevertheless revered by the players of the orchestra, whose respect for him was not diminished by the high standards he insisted upon at each rehearsal and every performance. In reflecting upon playing under Toscanini, legendary trumpeter Harry Glantz recalled, “He would inject himself into the orchestra. . . . He would draw the gift that you were endowed with out of you.” What the maestro possessed, Glantz claimed, was something no other conductor had: the ability to “instill in you his passion, his love, his gift and fire of music.” His players raved about his skill with the baton, a sentiment captured by the violinist Sylvan Shulman, who said he had the “most beautiful technique I’ve ever seen.” The violinist raved, “I’ve never seen a ballerina look more beautiful.” However lovely his beat, his temper could be terrifying. He would often cut you to pieces, recalled French horn player Harry Berv. But given the chance to live his orchestral life over again, Berv would not have wanted to play under anyone else.20

Revered by critics and adored by musicians, Toscanini would become one of the most admired musicians in the world, and his politics played a critical part in the transcendent status he achieved in twentieth-century American life. Even before his break with Bayreuth in 1933, the conductor’s career had become enmeshed in fascist politics. And still earlier, Toscanini had received praise for his fearless service during the Great War. The conductor, who would be decorated for valor, performed nobly in 1917, when the military band he had established performed under fire during the battle of Monte Santo. According to a newspaper account, the maestro conducted the band during a furious Austrian barrage, leading the ensemble to an advanced position, where, protected by an enormous rock, they played until word reached Toscanini that the Italian soldiers had taken the Austrian trenches, a feat accomplished with the sound of “martial music” in their ears. After each piece, Toscanini reportedly shouted, “Viva l’Italia! ” He and his musicians emerged unhurt, though the same could not be said for the bass drum, which was torn by shrapnel.21

With the First World War over, Toscanini crossed paths with Benito Mussolini. While uncertainty remains about when precisely the two men first met, the musician was initially impressed by the Italian journalist, who was laying the groundwork for the regime that would one day wreak havoc in Europe and beyond.22 Attracted to what, for some, were the appealing principles of fascism, Toscanini backed the party’s program in 1919, which at the time was ideologically different from what it would soon become.23 In that year’s parliamentary elections, Toscanini allowed his name to be placed on a list of candidates for Mussolini’s party, though the organization believed it stood no chance of winning. While the maestro did not engage in active campaigning, he did donate 30,000 lire to the party, which had little effect on the outcome. Receiving only a few thousand votes in Milan, the party was trounced in the election and even Mussolini was defeated. Thus ended the musician’s formal political career, an ignominious experience that caused him considerable regret in later years, especially as he became a determined foe of Mussolini.24

Indeed, in Milan a few years later, the conductor engaged in a musical wrestling match with Mussolini’s backers, who had come to power after resorting to violence and assuming an antidemocratic posture, a stance that turned Toscanini’s early enthusiasm into overt disgust. During a performance of Falstaff at La Scala in December 1922, supporters of the Italian autocrat demanded that the conductor play the Fascist Party hymn, “Giovinezza” (“Youth”), as he entered the pit to begin the opera’s third act. Ignoring the chants, Toscanini began to conduct the Verdi, but was soon forced to halt the proceedings as the boisterous demands persisted. After breaking his baton in anger, the maestro stormed from the pit, shouting and cursing, and a long wait began. A member of the company’s staff announced the fascist hymn would be played at the end of the opera, whereupon Toscanini returned and completed the performance. The manager then told the performers to stay where they were and to sing the hymn accompanied by the piano. Toscanini would have none of it. “They’re not going to sing a damned thing,” he declared. “La Scala artists aren’t vaudeville singers.” He then ordered everyone to their dressing rooms, after which the hymn was played at the piano, with Toscanini claiming the orchestra did not know it.25

As the incident suggests, and there would be many such episodes along the way, the maestro had a penchant for assuming unyielding, unambiguous, and even unpopular political positions in the face of what he perceived to be antidemocratic behavior by the powerful. A few weeks before the Falstaff episode, after Mussolini had come to power, the conductor had declared, “If I were capable of killing a man, I would kill Mussolini.”26 Just as holding singers and instrumentalists to exacting standards was one of Toscanini’s signal characteristics as a musician, in the political realm, he refused to truckle to immoral behavior. One must adhere to one’s ideals, whether one was a soprano, a violinist, a political leader, or the head of a celebrated music festival.

While there were other clashes between Toscanini and the Mussolini regime,27 in 1931, tensions between the conductor and the Italian fascists led to a celebrated confrontation, which attracted considerable attention across the United States. Appearing in Bologna in May for two concerts, which overlapped with a Fascist Party meeting, Toscanini, now working in New York, was once more drawn into Italian politics. Yet again, Italian patriotic music was the catalyst.28

On the day of the first Bologna concert, Toscanini was asked to conduct the fascist hymn and the royal anthem because government ministers would be in the audience that night, a request he refused. A few hours later, an arrangement was worked out that was agreeable to Toscanini by which a military band would play the anthems in the theater’s lobby as the ministers entered the building. But soon afterward, that plan was altered, and the conductor was ordered to play the patriotic pieces, a directive he again rejected. Finally, the maestro learned the ministers had decided not to attend the performance, meaning there would be no nationalistic melodies. But Toscanini’s unwillingness to comply with the earlier requests had circulated among a group of fascists who gathered outside the theater that night to await his arrival, whereupon they demanded to know whether he was willing to play “Giovinezza.” He would not, he declared, and as the maestro tried to enter the theater, the young ruffians began hitting him in the face and head. His chauffeur, along with Toscanini’s wife and a friend, hustled the musician back into the car and sped to their hotel. Inside the theater it was announced that the concert would be postponed because Toscanini was ill, a declaration greeted with derision and shouts of “It’s not true!”29

Though the conductor and his party reached their hotel safely, soon afterward, a few hundred fascist activists who had marched from party headquarters to the hotel (some singing the music Toscanini had refused to play) began demonstrating beneath the conductor’s hotel window, shouting threats and hurling obscenities his way. Upstairs, with cuts on his face and neck, Toscanini was in a foul mood, behaving, according to one observer, “like a caged bear.” Later that night, the Toscaninis were told that their safety could not be guaranteed and that they should leave the city by six in the morning. They heeded this advice shortly before 1:30 A.M., heading by car to Milan, which they reached at dawn. They were then placed under government surveillance and relieved of their passports, their fate uncertain. At this point the Italian government seemed unsure about what to do with the recalcitrant musician who had become a virtual prisoner in his own home.30

From New York to San Francisco, from Baltimore to Los Angeles, the press presented the story of what had happened to Toscanini and his party: the attack outside the theater, the escape to the hotel where a mob had gathered, the drive to Milan, the confiscation of the maestro’s passport, the posting of soldiers outside his Milan home, the arrest of pro-Toscanini demonstrators in Milan, and the emotional stress the ordeal was causing the musician.31 The Toscanini affair exposed the American public to the gangsterism that characterized life in fascist Italy under Mussolini, who, for a time, had maintained support among many Americans, especially in elite circles.

Shortly after being chased from the theater in Bologna, Toscanini wrote the Italian leader to explain what had occurred, in order, he noted, that Mussolini would not base his understanding of events on “false information.” While the contents of the letter were not published in the United States until years later, the American public learned about the conductor’s message to the Italian politician at the time it was sent, powerfully reinforcing the notion of an idealistic artist taking a principled stand against an oppressive regime. While Toscanini received no response to his letter, Mussolini was said to have observed privately, “He conducts an orchestra of one hundred people; I have to conduct one of forty million, and they are not all virtuosi.” And just after the attack, upon hearing what had happened, the Italian leader reportedly declared, “I am really happy. It will teach a lesson to these boorish musicians.”32

But Mussolini could not have been happy with the outpouring of support in the United States and elsewhere for Toscanini, who remained holed up in his Milan home. Celebrated musicians, important figures in American academia like John Dewey, Frank Taussig, and Robert Morss Lovett,33 along with the general public expressed their admiration for the conductor, while proclaiming their hostility for the fascist regime and its shameful treatment of a musical icon. Americans read about the strong stand taken by Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor of the Boston Symphony. In a cable to La Scala, Boston’s maestro spoke of the “outrage” that had been perpetrated against Toscanini. As a result, Koussevitzky asserted, he would sever his relationship with the opera company, which led La Scala’s manager to respond that such a reaction was unnecessary.34 According to Koussevitzky, he had endured “too much from the Bolshevists to tolerate what the Fascists are doing to artists.” Toscanini belonged not merely to Italy, but to the world. An impassioned Koussevitzky insisted that artists should not “remain indifferent to the fate of a colleague who is exposed to blows and persecution” because he refused to “mix politics with art.”35

Other musical leaders weighed in, including Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the Detroit Symphony conductor, who also withdrew from concerts scheduled in Italy. He, too, was “outraged” by what had occurred in Bologna: “A handful of ruffians simply appointed themselves as Toscanini’s judges and executioners and abused a man the whole world venerates.”36 Adding their voices to the chorus were conductors Leopold Stokowski and Walter Damrosch, the former calling for a protest among the world’s leading musicians. Toscanini was right not to play the Fascist Party hymn, Stokowski said. The concert hall was “no place for politics.” Recalling the dilemma some conductors faced in an earlier time, Damrosch supported Toscanini’s unwillingness to open the concert with “patriotic hymns.”37

The forceful reaction of the American music community, visits from Italian musical figures, a statement of support from composer Béla Bartók, and some fifteen thousand letters and telegrams that reached Toscanini from all over the world suggested that the 1931 affair was not, as Mussolini had claimed, “a banal incident.”38 Indeed, before the conductor left Milan on June 10 for a short rest in Switzerland, after which he would take up his baton at Bayreuth, the overwhelming sense prevailed that the sixty-four-year-old musician had bested Mussolini and his gang.39

If the Bologna affair fortified America’s admiration for the Italian conductor, it also made vivid to many Americans the malevolence of European fascism. As a Philadelphia Inquirer editorial observed in May 1931, while some had believed fascism was beneficial for Italy, it was clear that the movement had become “a peculiarly mean kind of despotism.”40 The following month, a lengthy New York Times piece documented the entire incident. Describing the “Fascist assault” on Toscanini, the story asserted that the regime had sought to break his “spirit.”41 But he would not surrender to his tormentors, who had transformed the maestro into “a hero and a martyr.”42

In April 1933, as I discussed at the start of the chapter, Toscanini again confronted fascism in Europe. Taking a stand as conductor of the New York Philharmonic against the persecution of musicians in Germany, the Italian maestro and ten others cabled Hitler. As Americans would learn, the original idea for sending the petition to the dictator had come from Maestro Bodanzky at the Met, who suggested in March that the support of celebrated figures from the American music world should be solicited for the task. American readers also learned that Toscanini was considering withdrawing from Bayreuth, and that he had been under pressure to do so from leading musicians who believed it would represent a forceful protest against the Nazi regime.43

Providing the background story for the Hitler cable, news reports cited the correspondence from Ossip Gabrilowitsch to Toscanini and Berthold Neuer, an official of the Knabe Piano Company, whom Bodanzky had initially contacted about the idea, and who drafted the letter and arranged for its transmission to Berlin. Readers learned that Gabrilowitsch, upon receiving a draft of the cable from Neuer, wrote that he was not in the “least bit afraid” to include his name, adding, “I am not enchanted over the idea of addressing as ‘your Excellency’ a man for whom I have not the slightest respect.” Mincing no words, Gabrilowitsch declared, “Neither do I think it quite truthful to say ‘We are convinced that such persecutions are not based on your instructions,’ whereas in reality I am thoroughly convinced that Hitler is personally responsible for all that is going on in Germany.”44

Gabrilowitsch’s concerns went unheeded. More significantly, newspaper readers could reflect on his correspondence with Toscanini concerning European developments. In trying to convince the Italian to participate in the effort, Gabrilowitsch said the cable would have little impact upon Hitler unless Toscanini signed his name. The Italian responded with conviction, proposing that his name top the list. Gabrilowitsch also raised the subject of Toscanini’s apparent willingness to conduct at Bayreuth in the coming summer, when “Hitlerism” was triumphant. As Gabrilowitsch pointed out, in 1931, it was reported that Toscanini had considered leaving Bayreuth because of his opposition to Hitler. If he returned this year, Gabrilowitsch suggested, that could be perceived by the world as reflecting “your approval of Hitlerism.” He then explained what Hitlerism represented, insisting it should not be seen “merely as an anti-Jewish movement.” That was one side of it, wrote Gabrilowitsch, the Russian-born son of a Jewish father. But Hitlerism was also “a mental attitude which advocates brutal force against liberty. It is the worst side of fascism.” Melding this to Toscanini’s personal experiences, Gabrilowitsch noted that the “outrageous insults to which you were subjected in Bologna” exemplify that attitude. He reminded his colleague that the world’s musicians had proclaimed their “indignation and sympathy” for him in 1931 and asked whether Toscanini was prepared to do the same for oppressed colleagues inside Germany. Would he conduct at Bayreuth? You might say that Bayreuth is “not responsible for Hitler.” But it was understood to be a center of “extreme German nationalism,” a place filled with Hitler’s friends and admirers. Gabrilowitsch drove the point home: “Under those conditions, will you . . . the world’s most illustrious artist—lend the glamour of your international fame to the Baireuth [sic] festival?”45

Two days after the April 1 cable to Hitler, in a letter not made public, Hitler wrote to Toscanini that he hoped that summer at Bayeuth to “thank you, the great representative of art and of a people friendly to Germany, for your participation in the great Master’s work.”46 Despite this ostensibly conciliatory gesture, the Nazi regime issued instructions the next day banning the recordings and compositions from state radio and the concert hall of those who had been party to the cable. The public announcement of this policy was reported in the United States, thus fortifying the realization that the Nazis were abridging artistic expression.47

But a crucial question remained: Would the world’s most famous conductor return to Bayreuth in 1933? While today it is difficult to imagine such a question providing grist for public debate and widespread news coverage, in the 1930s, the matter was seen as highly consequential. The Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler issued a public statement asserting that the conductor should return to Bayreuth, because only then could he defend the sacred principle that “artistic utterance” should remain outside the “sphere of political and racial strife.” Such a stance, Kreisler averred, was integral to the preservation of untrammeled artistic expression. In Bayreuth, Toscanini could serve as a “herald of love and a messenger of good-will.” Moreover, the Austrian declared, those urging Toscanini to step down did not understand Germany’s recent history, which since the war had left the people in an overly emotional condition. In time, Kreisler believed, the country and its leaders would “face their domestic and external problems with their traditional sobriety and sense of order.”48

While the next ten years would prove Kreisler a better violinist than a prophet, his reproof of those who encouraged boycotting Bayreuth was worthy of reflection, especially in 1933, since the horrors Nazi Germany was capable of perpetrating were then unknowable. One would surely have pondered the idea that Toscanini’s presence at Bayreuth might enhance the possibility for change in Germany, and there was something both laudable and naive in Kreisler’s unwillingness to believe that it was far better for the famed conductor to stand aside at this perilous moment in the history of the world—when the “nerves of all nations are on edge and sinister grumblings of war are heard again.”49

From within Germany, thoughts on the dilemma that Toscanini faced made their way to America, as Winifred Wagner, the widow of the composer’s son and also a close friend of Adolf Hitler, claimed the Italian conductor would not step away from Bayreuth.50 Whatever Frau Wagner believed, reports filtered back to the United States which suggested that those connected to the festival were deeply worried that unfolding musical developments in Germany might mean that foreigners would refuse to attend.51

But the distinguished maestro had made no final decision about his summer labors, though in an altogether courteous letter to Hitler in late April, Toscanini thanked the German chancellor for writing. He apologized for not replying sooner and indicated he still hoped to conduct at Bayreuth that summer. “You know how closely I feel attached to Bayreuth and what deep pleasure it gives me to consecrate my ‘Something’ to a genius like Wagner whom I love so boundlessly.” It would be profoundly disappointing, he told the German leader, should “circumstances’’ arise that would make it impossible to participate in the festival. With more than a touch of deference, the musician concluded his message by thanking Hitler for his “kind expressions of thought.”52

A few days later, Toscanini decided he would in fact not conduct at Bayreuth that summer. In a letter to festival officials, he conveyed his decision, though he offered little elaboration. He said the distressing developments in Germany had caused him considerable pain as a man and an artist. He went on to note that he was obliged to inform the festival’s officials that he would not be attending Bayreuth. In a rather gracious conclusion to his letter, the esteemed conductor pointed out that his kind feelings for “the house of Wagner” remained unchanged.53

A few weeks before Toscanini’s public announcement, the American press reported that the 120th anniversary of Wagner’s birth had been celebrated enthusiastically by the Nazi regime on May 23 at Bayreuth’s Festival Theater, with the Nazi flag flying from the building. Outside the theater stood detachments of storm troopers, guards, and Nazi youths, while inside a ceremony unfolded, led by a Nazi official. On a wreath emblazoned with a swastika, words made clear the ostensible link between Nazism and the creative life of Wagner: “Just as the National Socialists must fight today, so Richard Wagner in time past had to fight all the world on behalf of German culture and the German spirit.” As the ceremony ended, an ensemble the New York Times described as a “Nazi symphony orchestra” played Wagner’s music.54

For Toscanini, the concerns that had caused him distress would become intolerable. Even two years before, in 1931, having completed his work at Bayreuth, he had voiced reservations about continuing there, calling it a “banal theater,” a place plagued by the sort of problems (a mediocre orchestra) one expected to encounter in less august settings. Still more repugnant was what one newspaper described as Toscanini’s sense that a “materialistic and commercial spirit” characterized the festival. He had also expressed concerns about the devotion Winifred Wagner, the widow of the composer’s son, had to Hitler, which Toscanini believed caused Wagner’s music to be “degraded to the role of a Hitler propagandist.”55 If the maestro found such things troubling in 1931, by 1933, with Hitler elevated to chancellor and the artistic situation deteriorating mercilessly for Jews and other enemies of the state, Toscanini’s anguish was still more intense.

When on June 6 the American press reported that Toscanini had decided not to conduct at Bayreuth that summer, some papers quoted from a telegram he had sent Winifred Wagner a week earlier, a version of the letter quoted above. Referring to the persecution of Jewish musicians in Germany, which had troubled him since mid-March, Toscanini wrote that the “lamentable events which injured my sentiments as a man and artist” were the same as before, though he had hoped for a change. The coverage of the decision supplied background on Toscanini’s distress and on recent developments, including the cable to Hitler and the ban Nazi officials had placed on the Italian’s recordings.56 Commenting on Toscanini’s decision, a Baltimore Sun editorial noted that Toscanini’s towering reputation and well-known gift for interpreting Wagner meant his absence would be quite significant. A “Wagnerian festival without Toscanini” would be as much an anomaly as a Wagner festival without Wagner’s music. Offering a stern judgment on German oppression, New York’s Herald Tribune asserted that “Bayreuth could not hope to remain the shrine of music . . . if the artists of any race” are kept away. In a letter to the same paper, one reader, Samuel Weintraub, said he hoped the “absence of the master from the temple” would cause the Germans “to realize that there is something wrong in their land.”57

Press coverage of Toscanini’s decision and Germany’s reaction shed light on what it was like to live under a regime intent on jettisoning the norms of civilized behavior. Germany was “relapsing into aesthetic barbarism,” the Philadelphia Inquirer declared in an editorial titled “Maestro Toscanini’s Protest.” Hitler’s Germany was a land in which books were burned, scholars were ousted from their positions, and capable workers were discharged.58 And according to the New York Times, the conductor’s decision had demonstrated to the “music-loving German masses the full weight of world condemnation” of their government’s policies.59

A few months after he announced his decision, Toscanini was acclaimed as “a great friend of justice, truth and freedom” by a leading Jewish organization, the Jewish National Fund of America, whose president, Dr. Israel Goldstein, presented him with an award for protesting Nazi policies toward Jews in Germany. Toscanini, in New York, was said to be profoundly moved and determined not to take part in any “musical activities” in Germany as long as the Germans continued persecuting “innocent people.” As Goldstein told the conductor, “millions of hearts had gone out to you in love and admiration for the personal sacrifice you made in behalf of a noble principle.”60

In the spring of 1936, with his fame and ability undiminished, Toscanini decided to step down from his post at the Philharmonic. Sixty-eight years old, the Italian had been associated with the orchestra for more than a decade and was, according to biographer Harvey Sachs, worn down by the ensemble’s brutal schedule. While the Philharmonic’s management tried to convince him to remain, perhaps with a reduced conducting load, the musician had made up his mind, and in February the announcement came.61 In late April, Toscanini would conduct his final concerts as head of the orchestra, performances that were among the most memorable in the history of the city’s symphonic life.62

Now only one question animated the classical music world: Who could possibly succeed Toscanini?63 Within days, the matter of replacing America’s most celebrated conductor would be enmeshed in foreign affairs, as the name of the renowned Wilhelm Furtwängler was atop the Philharmonic’s list of potential successors. Fifty years old and born in Berlin, Furtwängler spent much of his childhood in Munich, where he studied piano and composition from an early age. By the time he was twenty, he was conducting at the Zurich Opera, and over the next several years, as his reputation grew, Furtwängler would hold a variety of increasingly important positions in Germany. In 1922, he was chosen to direct the Berlin Philharmonic, one of Europe’s finest ensembles.64

When in February 1936 the New York Philharmonic announced that Furtwängler had agreed to succeed Toscanini, the local press covered the appointment closely, and papers and magazines across the country informed readers that, starting the following season, the man considered Europe’s most distinguished conductor was set to ply his craft in New York. The orchestra’s announcement described the German-born conductor as “a rare musician, of catholic taste,” an artist renowned for his “profound and stirring interpretations.” As the statement noted, this would not be Furtwängler’s first sojourn to the United States. Some ten years earlier, in 1925, he had debuted with the Philharmonic in what was described as a “memorable evening,” the first of ten concerts he directed that season. And over the next two seasons, he led some sixty concerts with the orchestra.65

Although just ten years had passed since those appearances, the 1930s were a different time, and many American concertgoers were no longer content to bask in the glow of the German conductor’s interpretive gifts, which reflected an approach that was the polar opposite of Toscanini’s. As one musician has written, many believed Furtwängler brought to the podium a “more subjective, fluid” style, marked by an almost “improvisational” quality. However one perceived the German’s approach, and whether one was mesmerized by his “priestly aura” on stage, in the 1930s, an artist who could be linked to the Nazi regime—and many did just that with Wilhelm Furtwängler—was no longer a compelling presence in an American concert hall.66 Though some believed he had behaved honorably under challenging circumstances, others were convinced that Furtwängler’s actions between 1933, when Hitler came to power, and the current moment, rendered him a pariah in American musical life. And this controversy, which turned on whether Furtwängler was a Nazi sympathizer, a dupe who was allowing the Hitler regime to use him for its own purposes, or a principled opponent of the Nazis, made his appointment enormously contentious.

Whatever ambiguity surrounded Furtwängler’s behavior, opposition to his selection erupted immediately and emerged from a variety of sources. Within one day of the announcement, a group of Philharmonic subscribers cancelled their subscriptions for the next season. Their spokesman, Ira Hirschmann, a business executive and a music lecturer at the New School, acknowledged that Furtwängler was one of the world’s leading musicians, but he called it “unthinkable” to appoint an “official of the Nazi government” to lead America’s foremost musical organization. Hirschmann suggested the orchestra’s finances were already on unsteady ground and claimed the withdrawal of subscribers would prove ruinous. He noted that he had spoken about the appointment with New York’s Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who appeared to agree with the opponents’ concerns.67 The message Hirschmann sent to the orchestra’s administration captured the stakes involved: The choice we face is “either to compromise ourselves as the sworn devotees of the cause of democracy as opposed to the Nazi dictatorship, or to welcome, recognize and acknowledge an official representative of that dictatorship.”68

Wilhelm Furtwängler

A few days later, the teachers’ and musicians’ unions added to what one newspaper called the “mounting chorus of protest.” While acknowledging that Furtwängler was a gifted artist, Charles J. Hendley, the head of the teachers’ union, labeled the conductor “a representative of the Nazi state.” Let him repudiate Hitler’s “barbaric rule” before he is permitted to raise “his baton over an orchestra.” At the same time, an organization of conductors and musicians contacted the American Federation of Musicians and the American Federation of Labor, urging them to reject the idea that members of the musicians’ union would play under a man devoted to a regime whose “ideals and purposes” were antithetical to the values of both groups.69

Across the city, opposition mushroomed, exacerbated by the fact that just one day after the announcement, the German government issued a statement of its own: Furtwängler would return to conduct at the Berlin State Opera, a plan, it was later learned, Hermann Göring, the Prussian Interior Minister, had choreographed to raise American hackles.70 (Furtwängler had left the position in 1934 after a quarrel with the Nazi leadership.) Among the groups formed to protest Furtwängler’s New York appointment, one established a committee that cabled the conductor in an effort to understand the extent of his sympathies for the Nazi regime. The committee’s chair, Dr. Frank Bohn, said they would ask him the “one question which the directors of the [orchestra] apparently failed to ask,” namely, “Are you sympathetic with the present Nazi government?” According to Bohn, the German’s record was characterized by “occasional mild protests and consistent capitulation to the Nazi authorities.” Bohn’s group would reach out to music lovers in order to “save the Philharmonic from its own self-destruction.”71 Another organization, the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League, whose executive secretary was George E. Harriman, said that unless Furtwängler renounced Nazi “principles,” they intended to make his stay in New York “unsuccessful.”72 Declaring that the league believed the conductor was complicit in the activities of the German government, Harriman insisted that Furtwängler was a representative of the Nazi leadership. This question—to what extent Furtwängler supported and was complicit in the policies of Nazi Germany—was the most contentious aspect of the entire episode.73

The Furtwängler affair led many to write heartfelt letters to the local papers. A Brooklyn Eagle reader, Annie Elish, said that one had to consider who the Nazis were and what they stood for. According to Elish, Stalin was the “father of Nazism,” Mussolini was “unbearable,” and Hitler was “abominable.” And why, she asked, would Americans “import” a man lacking in “soul to interpret . . . music, which goes straight to the soul?”74 Writing to the New York Times, Julia Schachat said her family would no longer attend Philharmonic concerts, since the ensemble had chosen a “Nazi” to replace Toscanini, who had taken a stand on Hitler’s policies against “Jewish musicians.”75 Expressing similar views, Judith Ish-Kishor explained that she, too, would cancel her subscription because it was clear that “Nazism and not the spirit of music will [now] dominate the atmosphere of the Philharmonic.” As a “member of the race which they abuse,” Ish-Kishor was stunned that the “sanctuary of music in America had been successfully invaded by the hordes of Hitler.”76

Among the more thought-provoking reactions to appear was a letter from H. M. Kallen, undoubtedly the distinguished philosopher Horace M. Kallen, then associated with the New School. Kallen shared an intriguing idea with Times readers, designed to test Furtwängler’s fidelity to liberal principles. Since Furtwängler’s opponents had not questioned his ability as a conductor, Kallen suggested they feared the “prostitution of his great talents to the policies . . . of Hitler’s Nazis.” Kallen pointed to a report about a recent Vienna Philharmonic program in Budapest, which saw Furtwängler replace a piece by Mendelssohn, whose music the Nazis had banned, with a composition acceptable to the regime. Addressing the concerns of those distressed by the appointment, Kallen offered an approach to allay their worries. The Philharmonic should announce a program to be conducted by Furtwängler the following year, which would include compositions banned in Nazi Germany. How simple it would be to include the works of composers such as Mendelssohn, Mahler, and Schoenberg on the program Furtwängler was scheduled to conduct. If all went well, this would vindicate completely the orchestra’s decision and Furtwängler, Kallen claimed.77

Despite this measured plan, the city’s musical waters remained choppy, as Furtwängler and the orchestra’s hiring committee endured withering criticism. To understand why they thought Furtwängler was a good choice to head the Philharmonic, one must consider both his status and his recent activities in Germany.

On purely musical grounds, Furtwängler was, without question, a conductor of the highest rank, which made him a reasonable choice to succeed Toscanini. Moreover, the Italian maestro had recommended the German to the orchestra, a decision, according to Harvey Sachs, motivated by Toscanini’s high regard for Furtwängler’s ability and because he wished to offer Furtwängler an opportunity to leave Germany. This, Toscanini believed, was an artist’s only moral choice.78 Beyond this, Furtwängler’s professional behavior in Nazi Germany during these years allowed some to argue that he had comported himself honorably in the face of Hitler’s toxic policies. Furtwängler was not a member of the Nazi Party, and there was considerable evidence pointing to his opposition to the Hitler regime, in both its repressive actions and ideological foundation.

Though it was not clear how much Furtwängler was doing to save Jewish musicians, it became known that he had refused to dismiss Jews from his orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic. While Americans were not yet completely familiar with his actions, what had been widely reported was the public letter Furtwängler had written in April 1933 to Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, protesting the persecution of Jewish musicians, or at least the mistreatment of those who, in Furtwängler’s formulation, had done nothing to warrant it. If aspects of Furtwängler’s reasoning were disturbing and framed to appeal to Nazi officials—he suggested “real artists” should be left alone, while the fight could be directed against those whose spirit was “rootless, disintegrating, shallow, [and] destructive”—he seemed to reject the Nazis’ uncompromising policy of persecuting all Jewish artists, a view he was willing to express publicly.79

The following year, in November 1934, Furtwängler was involved in another celebrated affair in which he made a second public declaration, this time in defense of German composer Paul Hindemith, who, though not a Jew, had come under a state-sponsored attack due to the alleged “degenerate” character of his music, which Hitler loathed. It did not help Hindemith’s cause that his wife and some of his close musical associates were Jewish, thus making his “decadent” music even more unpalatable and his status still more perilous. The Hindemith episode, which received international attention, led Furtwängler to resign his positions at the Berlin Philharmonic and the State Opera, a decision which, for a time, enhanced his reputation and convinced some that he was not reluctant to stand up to the thuggery that characterized life under Hitler.80

In New York, the Times portrayed Furtwängler’s behavior in the Hindemith affair in almost heroic terms, claiming the conductor had “often courageously defended artistic interests against anti-Jewish . . . tendencies.” Quoting Furtwängler’s bold words on the subject, the press had helped fortify his standing, as when he spoke candidly about the question of artistic expression. “What would we come to,” he asked, “if political denunciations were to be turned unchecked against art?”81 Columbia University music professor Daniel Gregory Mason weighed in, calling Furtwängler’s resignation, a “splendid and inspiring” act, which served as a “warning to the Nazi government that politics has no place in the realm of art.”82

Americans reflected upon the German musician’s willingness to challenge Nazi values, which he demonstrated by defending Hindemith. According to the conductor, it was a “question of principle. We cannot afford to renounce a man like Hindemith.”83 The publication of Furtwängler’s statement in a leading German newspaper had created a stir in that country, and a blistering response directed at both conductor and composer followed from the Nazi Chamber of Culture. To an American, Furtwängler would have seemed a defender of artistic liberty, and his decision to resign as director of the State Opera and conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, the two most important musical positions in Germany, suggested his unwillingness to compromise in the face of Nazi demands.84 Writing from Berlin in the New York Times, music critic Herbert F. Peyser observed that Furtwängler’s dual resignations represented a “crossing of the Rubicon,” which placed him in the anti-Nazi camp.85

Whatever his bold statements, within months of his dual resignations in 1934, Furtwängler was again standing before the Berlin Philharmonic. After a reconciliation with the Nazi leadership, which included meetings with Goebbels and Hitler, he returned to the podium on April 25, 1935, to conduct what, until recently, had been his orchestra.86 According to Time, it was not clear whether “Furtwängler had swallowed his artistic conscience or whether Nazi Germany suddenly decided it could dispense with him no longer.” What was clear was the response of the Berlin audience, which, Americans learned, offered a tumultuous welcome when Furtwängler returned to the stage.87

Just as Berliners were thrilled to welcome Furtwängler back, a contingent of Americans, believing his artistry would enrich their country’s cultural life, expressed support for his New York appointment. In the wake of the Philharmonic’s announcement in February 1936, those supportive voices could be heard, even if they were in the minority. A Washington Post editorial pointed to the “wisdom” of the choice, and touching on the Hindemith episode, contended that Furtwängler’s “temporary disgrace with the Nazi regime was all to his credit.” As the editors made clear, the Philharmonic’s selection was entirely sensible.88

Also backing the German musician were three writers to the New York Times, one celebrated, and all of a universalist bent. Brooklynite Bernice Sara Cooper considered the significance of music, noting that German soprano Lotte Lehmann had said that “music brings the peoples of the world together, while politics divides them.” Just because the Nazis rejected this view, Cooper asserted, did not mean Americans should disregard it.89 In a short letter, Franz Boas, the distinguished German-born anthropologist at Columbia University, expressed surprise about the opposition to the appointment. According to Boas, Americans objected strenuously to the “coercion of art and science and the intrusion of political motives into matters” unrelated to politics. While his observation was historically dubious, Boas warned the American people that they should take care not to commit the same mistakes that have “destroyed science and art in Germany.”90

A final pro-Furtwängler missive, penned by a William Harrar, featured a dram of sarcasm and a dash of anti-Semitism. Harrar wondered if New Yorkers feared an “Aryan reading” of Brahms's Fourth or Beethoven through “the veil of the swastika.” His response was clear. The “grandeur and beauty of symphonic music are completely divorced from any possible connection with politics.” The only criterion for selecting a conductor should be his skill. Should he provide “shoddy Wagner” and “spurious Bach, away with him!” But why care if a man has conducted the Berlin State Opera or “looked in his time on Hitler”? In considering—and disdaining—“the Jews and their sympathizers,” Harrar said their threat to boycott next season’s concerts revealed an “almost abject subservience to the intolerable example of Nazism.”91 Those upset by the prospect of hearing Furtwängler, Harrar believed, embraced values akin to those of the Nazis.

But few were as sanguine about bringing the German to New York as Harrar, Boas, and Cooper, and of the many who disagreed with their position, two publications offered especially scathing assessments of Furtwängler. The American Hebrew, a Jewish weekly, declared the Philharmonic should rescind the appointment at once, calling Furtwängler an “official agent of the Nazi government,” while the Marxist monthly the New Masses argued that not once during the last three years had Furtwängler acted out of anything resembling genuine moral conviction. He was self-interested and cared little for the rights of Jews, even those in his own orchestra.92 Similarly unimpressed with Furtwängler’s alleged defiance of the Nazi regime, the American Hebrew said his protests sought to “hoodwink” the world. Hardly a man of noble sentiment, Furtwängler was the “highest musical official of a government which . . . has relegated musical art to the gutter.”93

More sober but still critical in assessing the Furtwängler problem was one of New York’s most distinguished music critics, W. J. Henderson of the New York Sun, who provided one of the only critiques of the conductor’s interpretive skills. He spoke of Furtwängler’s disappointing earlier work in New York, which, after a promising start, descended into “mediocrity, mannerism, and platitude.” Turning to politics, Henderson called Furtwängler a “prominent and active Nazi,” which was not an unknown allegation. This was problematic, Henderson suggested, especially because at least half the New York Philharmonic’s patrons were of the “race” the Nazis had “singled out” for persecution. No musical organization could succeed in this “great Jewish city,” he asserted, without Jewish support. Deploying dubious empirical skills, Henderson claimed that even the “most casual observer” could see that “fully half of every audience consists of people of the Jewish race.” The orchestra’s decision-makers had made an “incomprehensible blunder.”94

The New York Post’s music critic Samuel Chotzinoff rebuked the orchestra’s board for the closed selection process, calling it wholly inadequate when the future of “Civilization” is uncertain. The current moment, Chotzinoff contended, was one in which the sanctity of the “human soul” was imperiled; even art, which once had stood above the fray, was being compelled to serve the “forces of darkness.” There were moments in the struggle for freedom, Chotzinoff claimed, “when principle must take precedence over art.” At such moments, the “fight for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is a sweeter theme than any . . . penned” by Beethoven. Furtwängler ought to sever his ties with the Nazis.95

With opposition rising inside and outside the music community, a tepid response emerged from the two principal characters in the drama, Furtwängler and the Philharmonic’s executive committee. The conductor issued a statement seeking to explain his position and to allay the concerns roiling the landscape. Traveling in Cairo, Furtwängler cabled, “I am not chief of the Berlin Opera but conduct as guest. My job is only music.”96 This succinct message represented the conductor’s attempt to highlight what he thought most important, namely, that he had assumed no permanent position in a state-sponsored musical institution and was not, therefore, a full-fledged part of the Nazi state apparatus. Moreover, Furtwängler suggested, as an artist, he stood above politics, an idea he would long maintain. For most observers in the United States, the first contention was a distinction without a difference, and the second, even if Furtwängler believed deeply in the notion, proved unconvincing. To those troubled by the appointment, Furtwängler’s reinstatement at the Berlin Opera, whatever his precise job description, demonstrated that he was part of the Nazi political and cultural establishment, which meant his position could not possibly be confined to music.

As the Philharmonic released Furtwängler’s cable to the press in a futile effort to quell the uproar, the orchestra’s executive committee issued a statement of its own explaining why the committee had chosen the German. Published widely, the statement claimed that press reports had given the impression that Furtwängler’s appointment had a “national or racial significance.” This idea was unfounded; indeed, Furtwängler’s selection was based solely on “artistic considerations.” Both Toscanini and the orchestra’s directors believed the German maestro, one of the world’s leading conductors, could generate enormous excitement among New York’s music public. He had been acclaimed wherever he performed, and it was incorrect to suggest that his engagement involved “recognition” of the Nazi regime or acceptance of its “artistic policies.” The committee also defended Furtwängler’s actions, claiming it was well to recall that he had “risked and sacrificed” his position in German musical life by “waging . . . earnestly and persistently, a contest for tolerance” and open-mindedness toward musicians and composers.97

While the Philharmonic’s statement had no impact on an unsettled situation, the manner in which the committee presented its message and its characterization of the opposition missed the point. Few opponents of the selection questioned Furtwängler’s conducting skills, though some offered critical commentary about what he would bring to the city’s musical life. Nor did most of his critics believe the Philharmonic’s board supported the Nazi regime or approved its artistic policies. As for the so-called risks and sacrifices Furtwängler had endured by advocating tolerance and open-mindedness, some doubted and even rejected such a claim. In the end, the opposition, while not monolithic in its views, questioned the morality of inviting to New York someone who had chosen to remain in Nazi Germany for the past three years, working as an artist when many of his colleagues, especially Jews, could no longer do so. Here was a man who had maintained a relationship, even if ill-defined, with some of the leading figures in the Nazi hierarchy. Exacerbating this, Furtwängler had been invited to lead one of America’s foremost cultural institutions in a city in which Jews comprised a significant segment of the population and a still larger portion of those involved in New York’s cultural life.

It was up to the Philharmonic’s executive board to act. A letter sent by member Walter W. Price to several others on the board outlined his evolving thinking on the controversy and asked the committee to reconsider the appointment. In a cover note to Charles Triller, another board member and apparently a good friend, Price quoted Shakespeare: “To thine own self be true,” while reminding his friend, “We all want to do right.” While he had done all he could to bring Furtwängler to the orchestra, he noted the controversy had caused him great distress.98

Price’s letter said he saw little merit in maintaining his stance out of fear of being labeled a “coward” because he was unwilling to “stick to his guns.” He had been pleased when Furtwängler had accepted the position, believing this would allow the orchestra to offer superb music with an esteemed conductor. Price acknowledged reading Henderson’s piece in the Sun and being in contact with Ira Hirschmann, whom he characterized as a man “opposed to any reason” on the subject. Certain developments had created “doubt” about the appointment, and that doubt was becoming “a conviction.”

Price told his fellow committee members that he had received a large number of letters from Jewish subscribers, passed along by the chair of the Ladies Committee, Mrs. Richard Whitney, who was trying to secure subscriptions for the following season. These were not “offensive,” Price observed, but expressed an understandable “resentment” against the decision to appoint Furtwängler, a man “whose sympathies are with the Nazi Government, at whose hands” Jews had received “treatment which they bitterly resent.” He encouraged the committee to read the letters, which he described as “calm and dignified.” While disturbed by the actions of those seeking to initiate a boycott against the orchestra, admit it or not, he wrote, all of us are animated by “a certain tribal instinct.” In some cases that instinct was “racial,” while in others it was “international.” Price then mixed this whiff of anti-Semitism with a touch of empathy, pointing out that Jews deeply resented Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies. “I cannot help saying . . . , would I not, as a Jew, feel justified in taking the positions which the Jews” have embraced. He noted his own anti-German bitterness, when, during the world war, he felt “hostility” toward all things German, believing Germany was responsible for the war.

The composition of the Philharmonic audience provided little cause for hope, Price acknowledged, since the “Jewish subscription” to the orchestra represented 50 percent of the seats sold, an assessment that rested (rather unscientifically) on his perusal of the audience from his Thursday night orchestra seats. This led Price to ask whether the institution had the “right, in opposition to [that] fifty per cent,” to maintain its position. Would bringing Furtwängler to New York be in the orchestra’s best interest, he wondered, and if the conductor came, could the organization address its financial challenges if its subscribers and the press were hostile to him?

After arguing that it was only fair to inform Furtwängler about the opposition to his selection, Price pointed out that five women on one of the Philharmonic committees, all of whom were Christian, had called the appointment a mistake. Finally, with more than a hint of condescension and another splash of anti-Semitism, Price registered distress over the behavior of the “representatives of the Jewish race in New York,” who, for “racial reasons and because of tribal instincts,” had opposed what the executive committee thought was in the “best interests of music.” Indeed, he resented it deeply. Nevertheless, the facts made it essential for the committee to reflect upon its decision, for the situation was more challenging than any the orchestra had ever faced.99

Price penned these reflections to his executive committee colleagues on March 9, 1936. Two days earlier, thirty-five thousand German troops had marched into the Rhineland in violation of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Pact of 1925. Remilitarizing the Rhineland, which one historian has called “Hitler’s most brazen gamble” to that point, received widespread coverage in the American press and did little to improve America’s view of Nazi Germany. While no direct link connected the developing Furtwängler affair to Hitler’s aggressive action, it is easy to imagine that the overseas crisis would have hardened the position of those opposing Furtwängler, a man seen as the instrument of a lawless regime.100

On the day the German army marched westward, flouting international law, the Reverend Harry Abramson wrote to Mrs. Richard Whitney of the Philharmonic’s Ladies Committee, responding to her invitation to subscribe to the orchestra’s 1936–1937 season. “Because of the appointment of the apostle and tool of Naziism [sic], Furtwaengler, I must decline to attend” the Philharmonic’s concerts. Abramson informed Whitney that he would use his influence with “relatives, friends, and parishoners [sic]” to convince them not to renew their subscriptions and not to attend future concerts. The orchestra had done a “dastardly thing in choosing Furtwaengler,” and he hoped the coming season would be the “worst failure” in its history.101

One week later, Furtwängler withdrew his acceptance. His short statement, sent from Luxor, Egypt, was at once high-minded and patronizing:

Political controversies disagreeable to me. Am not politician but exponent of German music, which belongs to all humanity regardless of politics. I propose postpone my season in the interests of the Philharmonic Society and music until the public realizes that politics and music are apart.102

Once again, Furtwängler had insisted that politics and art were discrete realms. He claimed that as an artist he stood outside the political sphere. His brief message suggested that he believed the American public, which viewed his appointment and actions as inseparable from German politics, was unable to grasp this evident truism. Music belonged to all, he theorized; yet the policies and ideology of the German government, which had allowed Furtwängler to return to the podium, belied the notion.

Even as the Philharmonic announced Furtwängler’s decision, which spared the orchestra from having to rethink its choice, the executive committee released a statement of its own, which was reported across the country. It “regretfully” accepted the German musician’s wishes and observed that New York was losing one of the world’s great conductors. The committee reminded the public that the German maestro was not a member of any political party in Germany, and it “deplore[d] the political implications that ha[d] been read into the appointment.”103

Furtwängler’s withdrawal occasioned no shortage of reaction across the country, with the majority of publications characterizing it positively. “Nazi Stays Home,” trumpeted a Time headline.104 And according to the Baltimore Sun, while Furtwängler believed politics and music should be kept separate, it was not clear he had observed that ideal in practice.105

In contrast, the Washington Post sought to take the high road, or so the editors likely imagined. The newspaper spoke of New York’s “intolerance and stupidity,” which had deprived the city of a distinguished conductor. Assuming a patronizing stance, the editors wondered whether the public could ever comprehend the chasm separating politics from the “universality of true art.” According to the Post, it was fatuous for Furtwängler’s detractors to claim that his appointment had any political significance. He had tried to steer clear of politics, and it was absurd to contend that his selection reflected support for the Nazi regime. Such a position, the paper argued, could be explained by the way “religious and racial hatreds” distorted people’s judgment. The editors then leveled one of the more shameful allegations to emerge during the entire episode, declaring that those responsible for Furtwängler’s resignation were “following in the footsteps of the Nazis” by viewing the “artist as a political agent of the state.” Furtwängler’s opponents were guilty of politicizing art.106

The New York press offered a more straightforward assessment of the episode. According to the Sun, those who had selected the German had disregarded the composition of the orchestra’s subscribers, the majority of whom were Jews, a group offended by the appointment of someone who was “generally” thought to be a Nazi and who certainly “enjoyed the favor of the Nazi government.” As a result, economic considerations explained the orchestra’s growing distress, as the executive committee feared Jewish subscribers would flee.107

Writing in the Brooklyn Eagle two weeks after the debacle ended, music critic Winthrop Sargeant reflected on the matter of boycotting musicians who, as in Furtwängler’s case, had compromised with the Nazi regime. As the conductor was an “officer of the German state,” it was appropriate in this instance, that “politics . . . took precedence over art.” But Sargeant wondered whether this should always be so, and he feared that in New York the balance might have tipped too far. The relationship between art and politics had assumed a wartime character, he suggested. There was a “cultural cost” to such musical “reprisals,” Sargeant explained, especially since Germany was the source of “modern musical culture.” To be sure, he did not defend developments inside Germany and he sympathized with those who wished to repudiate the Nazi regime. Nevertheless, Sargeant declared, the “hysteria” that led Germany to expel many of its leading musicians and ban some of its greatest compositions did not preclude questioning whether it was prudent to emulate Nazi musical policies.108

Whether New Yorkers would lament being deprived of a German contribution to the city’s musical culture remained an open question. What was certain was that Wilhelm Furtwängler would not conduct the New York Philharmonic in the fall of 1936. His fate had been sealed by the opposition that had boiled over in New York, especially among those who refused to support an artist whose ties to a malevolent regime were, at best, questionable—and possibly worse than that. While this would not be the end of America’s flirtation with the German conductor, his next opportunity to share his interpretive gifts with American audiences would not occur for more than a decade. That relationship, too, would not be consummated.

There was no small irony in the fact that on April 29, 1936, six weeks after the conclusion of the Furtwängler episode, when Arturo Toscanini returned to the stage after the intermission of his final concert with the Philharmonic, he conducted only Wagner, whose music had generated such fury not many years before. But now, a few weeks after New Yorkers had rallied to prevent a German conductor from coming to their city, the Carnegie Hall audience stamped and cheered when the “Ride of the Valkyries” brought Toscanini’s Philharmonic tenure to an end. In a city where riots had once exploded over performing Wagner, the crowd thrilled to the music.109 There was further irony in the fact that amidst New York’s convulsion over the Furtwängler appointment, another Philharmonic conductor with a history, Josef Stransky, passed from the scene at the age of sixty-one. As some surely recalled, in an earlier time, the talented Austrian had faced charges of disloyalty, which led many to try to knock him off the podium.110 Some twenty years later, Teutonic musicians, particularly those with dubious ties to unsavory regimes, could still inflame the public.

But the man Furtwängler was meant to replace, Arturo Toscanini, was not ready to lay down his baton. Although he had decided to step away from the Philharmonic, he would remain a leading figure in the classical-music world, and continue to play a key role in the developing conflict with Nazi Germany. In late February 1936, the month his resignation from the Philharmonic was announced, Toscanini accepted an invitation to go to Palestine to direct some concerts given by a new orchestra comprising Jewish musicians, many of whom were refugees from Hitler’s Germany. Helping to organize the ensemble was Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman, who invited the Italian to join him in this noble enterprise, claiming the maestro’s support would be crucial in both the fight against Nazism and the construction of Palestine. For his part, Toscanini asserted that it was everyone’s duty to help the cause.111 Privately, he wrote about his commitment to the new orchestra. Calling himself an “honorary Jew,” he said he would be leading some performances there.112

A few months after the announcement, Huberman let it be known that Toscanini’s first concert with the young ensemble would include the music of Mendelssohn, whose compositions the Nazis had banned. In performing music from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Toscanini was clearly determined to send a message to the Nazi leadership and to the people of Palestine.113

In December 1936, accompanied by his wife, Toscanini arrived in Palestine, where he would conduct the inaugural concerts of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, Alexandria, and Cairo. The ensemble had seventy-two musicians, of whom about half were German, while the rest hailed from Poland and Russia, with a handful from Palestine.114 During the Toscaninis’ stay, there was memorable music-making, of course, but the trip extended beyond the joys of the concert hall.115 After the first concert in Jerusalem, attended by sixteen hundred people, the maestro, sounding like a diplomat, said it was the “happiest moment” of his life. “Just think, to have been able to conduct a modern, first-class orchestra in the Holy City, the cradle of three great religions of the world.”116

Still more moving, New Yorkers learned, was Toscanini’s trip to a settlement, Ramot Hashavim, where he was greeted by a chorus of school children, who sang a Hebrew song composed for the occasion. The musician and his wife, accompanied by Huberman, were presented with the title and deed to an orange grove in the Jewish settlement, and given baskets of oranges, grapefruits, honey, and eggs. They were then taken to the mayor’s cottage, where they had a glass of wine and heard the history of the three-year-old settlement, which was peopled by sixty German refugee families. With no small pride, the mayor’s wife told Toscanini that the settlement possessed seven pianos. Clearly moved, the conductor told Huberman, “I never before saw a country as small as this where there was so much culture as among the Jewish farmer and labor classes.”117

If these were his public reflections, Toscanini’s private comments were still more effusive. Writing to a mistress from Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, he said, “From the moment I set foot in Palestine I’ve been living in a continuous exaltation of the soul.” He called Palestine the “land of miracles,” and said,

the Jews will eventually have to thank Hitler for having made them leave Germany. I’ve met marvelous people among these Jews chased out of Germany—cultivated people, doctors, lawyers, engineers, transformed into farmers, working the land, and where there were dunes, sand, a short time ago, today these areas have been transformed into olive groves and orange groves.118

If the maestro’s first trip to the Holy Land was remarkable, his return in the spring of 1938 was equally meaningful. The tale of the Toscaninis’ second trip, which included concerts in Haifa, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv, was described to New Yorkers in their daily papers and noted in other papers, as well. Among the journey’s emotional highpoints was a return to the Jewish settlement. This time, the settlers gathered to greet the couple, offering Mrs. Toscanini branches filled with orange blossoms from the Toscaninis’ grove and a basket of oranges for the maestro.119 As before, the concerts were extraordinary events. In Haifa, seventeen hundred heard him interpret Mendelssohn and Schubert, with many more turned away because they could not obtain tickets. The audience was thrilled and the curtain calls endless.120

In Tel Aviv, New Yorkers read, some three thousand filled the hall for a concert that was given especially for working people, though twice that number actually heard the performance, since by custom, those less well off shared their tickets with others at the intermission. Readers learned the maestro’s chauffeur, Morris Zlatopolsky, was disappointed that his wife had been unable to attend because she was pregnant. Upon hearing this, the conductor spoke with Mrs. Toscanini and the two proceeded to the chauffeur’s home to have tea with the driver and his wife. The Toscaninis wandered around Tel Aviv, entering small shops and watching children play. “I like to go into Jewish homes, eat Jewish food and feel the pulse of Jewish life,” the conductor explained.121

The ensemble’s offerings in Tel Aviv were striking, as Toscanini included Wagner on the program, marking the first time the composer’s music had been played in Palestine since Hitler came to power. Distilling a bitter debate that had raged for some time down to a simple statement, the maestro declared, “Nothing should interfere with music.”122