16 |

MALAYSIA 1965-1990 |

Singapore’s exit lowered the percentage of Chinese in Malaysia but did not alleviate the underlying tensions that had caused the split. In a way, the conflict between the PAP and the Alliance Party was symptomatic of the differing views of the Malaysian social contract. These divisions were not caused by the PAP but rather stemmed from the fact that a decade after independence, Malaysians had not defined a common destiny. The PAP had touched a nerve in all the communities. The inequalities inherent in the 1957 arrangement would not and could not go away. Malay economic grievances and Chinese political frustrations continued to simmer below the surface, waiting to boil over.

The differences that stood in the way of national unity were not just among the races but also within the races. In the Malay community, many saw little economic progress from the government that had replaced the British. In the Chinese community, there was a serious division between its representatives in the ruling party and ordinary citizens. Geographically, the northeastern parts of the peninsula and Borneo had societies far different from those in Kuala Lumpur and other communities on the western coast.

The disagreements of the 1950s had not been resolved. A new generation of Malays and Chinese in the peninsula had come of age, challenging the wisdom of the compromises made a decade earlier. The question of language had been postponed for ten years in the original constitution, and as the 1967 target date for the implementation of Malay as the sole national language approached, this became a highly emotional issue.

For the Chinese, the implications of the language change were both cultural and economic. Many Chinese felt their children would lose their Chinese heritage if they were educated in Malay rather than Chinese. At the same time, using Malay instead of English as the language of business and government would handicap the economic advancement of many non-Malays, whose Malay-language skills were none to poor. For most Malays, the issue was straightforward: Malaysia was their country; Malay was the national language; and it was time for the immigrants to accept that fact.

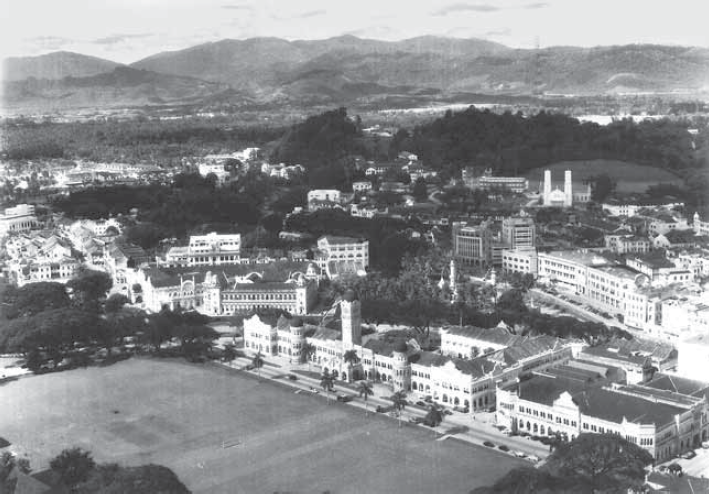

Kuala Lumpur in 1957 (top) and in the 1990s (bottom).

The National Language Act of 1967 pleased few people. In an attempt at compromise, the legislation made Malay the sole national and official language but allowed the continued use of English in the courts, higher education and specialized agencies. In government-aided schools, Chinese was to be phased out slowly, starting in secondary school and later spreading to primary school. Private schools could continue to teach in Chinese. The extremists in both major ethnic groups considered the law a sellout to the other race.

Opposition parties exploited the language issue and other grievances in the run-up to the 1969 election. PAS labeled the leadership of UMNO as tools of the Chinese and called for greater Malay domination of the economy and politics. It felt that the continuing poor economic position of Malays was due to UMNO compromise with the MCA and that a truly Malay government would take immediate steps to address Malay grievances and lay down the law to the immigrants.

Non-Malay discontent was heard through two new political parties, the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Malaysian People’s Movement). The DAP picked up the call for a Malaysian Malaysia. Although it professed to be multiracial and did have the occasional Malay candidate, its message of equal rights for all and its urban power base made it primarily a Chinese party. Gerakan was formed by a coalition of Malay and Chinese academics, professionals and opposition leaders. It held forth an ideal that all races could cooperate in a single party and that social justice would create a less stratified Malaysia. Gerakan’s problem was that its philosophy appealed primarily to urban and middle class voters, both of whom were mostly non-Malay.

The Alliance campaigned on a platform of its achievements – stability, economic progress for the nation and interracial cooperation – and its position as the party that had led Malaysia to independence. When the results were tallied, it received a rude jolt. Malaysian voters had rejected the status quo and elected opposition candidates. The Alliance’s percentage of the votes for parliament fell from 58 to 48 percent, and its percentage of votes for the state legislatures dropped from 57 to 47 percent. The Alliance still had a majority in parliament, but there was a significant migration of Malay support to PAS and non-Malay support to the DAP, PPP and Gerakan. Most of the seats that the Alliance retained were in constituencies with Malay majorities or large Malay minorities. In the Chinese-majority constituencies, the MCA was almost wiped out. UMNO’s numbers held better, but PAS had made significant inroads into its power base as over one in three Malays had voted against UMNO. The two-thirds majority in parliament that was needed to amend the constitution now depended on elections in the Borneo states, which had not yet been held.

At the state level, Gerakan secured a comfortable majority in the Penang state legislature, and PAS retained its control of Kelantan. In Perak, the PPP, the DAP and Gerakan won half the seats, which pointed to the possibility of a non-Malay state government. In Selangor, the state legislature was divided equally between the Alliance and an opposition made up of the DAP and Gerakan, creating another uncertain political situation.

The non-Malays had made their presence felt at the polls as never before. The results struck at the very heart of Malay assumptions of political dominance. It was possible that the sultans in traditionally Malay Perak and Selangor would have to deal with non-Malay chief ministers. The legitimacy of the social contract had been challenged by the people.

In the end, the future of the country was not decided in the ballot boxes but in the streets. Bloody race riots erupted in the aftermath of the election. The outbreak of disorder on May 13, 1969 was the result of racial tensions that had been building for some time. In many ways, it was the culmination of the fears that had been expressed during the PAP’s 1964 campaign for a Malaysian Malaysia.

The disturbances were ignited by non-Malay victory celebrations. Supporters of the victorious opposition parties marched through the streets of Kuala Lumpur, heralding a new political day. Many participants taunted Malay bystanders with “Death to the Malays!” and “Blood debts will be repaid with blood!” The thought of non-Malays controlling the government and the derisive attitude of the marchers touched off interracial fighting.

Selangor’s chief minister, Datuk Harun Idris, allowed his residence to be used as a staging area for disgruntled Malays, many of whom had been bused into the city from outlying areas. Old animosities and grudges resurfaced, and the façade of Malaysian stability and multiracial cooperation was destroyed. Armed confrontation took place between roving gangs of Malays and Chinese; shops were looted and houses burned. In the words of Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, “Kuala Lumpur was a city on fire.” The tensions spread beyond Kuala Lumpur, and the Tunku asked the king to declare a state of national emergency. The newly elected parliament was suspended, and elections in the Borneo states were postponed indefinitely. The army was called in to occupy many cities and towns, and a twenty-four-hour curfew was declared on the western coast. Hundreds were killed, hundreds more injured and millions of dollars of property damaged. Thousands were made homeless, and the future of the country seemed to hang in the balance.

In the initial stages of emergency rule, UMNO took control of the government. The day-to-day running of the country was turned over to a newly created National Operations Council (NOC) led by Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Razak. The NOC was organized in a manner similar to the government of the 1948–1960 communist Emergency. It consisted of UMNO politicians, senior civil servants, representatives from the military and police and one representative each from the MCA and MIC. The difference between the NOC and the Emergency government was that the NOC administrative apparatus and security were both in the hands of Malay leaders. The suspension of parliamentary democracy and UMNO’s takeover of the government sent strong messages to the country, especially that Malays continued to hold the levers of government, that the security forces supported them and that the political success of the non-Malay opposition had been an aberration.

The May riots marked the demise of the Tunku as Malaysia’s leader. Although he remained prime minister of the emergency cabinet, he had been discredited as a leader. His dreams of moderation and a multiracial society had been shattered. In 1970, he resigned and was succeeded by Tun Abdul Razak.

The riots and their aftermath sparked off a furious debate within UMNO about the country’s political system. The dispute was actually a fight for the soul of the party. One group called for the creation of a Malay government. UMNO could go it alone and would be more effective in looking after Malay interests if it did not have to make compromises with the MIC and MCA. This group consisted of old-line extremists, such as Tan Sri Ja’afar Albar, who had led the movement to arrest Lee Kuan Yew in 1965, and younger members led by Dr. Mahathir Mohamad of Kedah and Musa Hitam of Johor, who thought that the Tunku was too accommodating to non-Malays and were outspoken in their criticism of the administration.

On the other side were moderates led by Tun Abdul Razak, who felt that more had to be done in cooperation with the other races. Their attitude was reflected in the words of the Tunku: “What are we to do? Throw the Chinese and Indians into the sea?” In the end, the moderates won the day. Mahathir was expelled from UMNO, and Musa Hitam was sent to Britain on “study leave.” A new political and economic policy replaced the 1957 arrangement. It still favored the Malays and the basic premise of a multiracial and multicultural country was preserved, but Malays were to be integrated into all sectors of the economy. A National Cultural Policy set Malay culture, history and literature as the foundations of Malaysian heritage. Security forces were increased in case racial confrontations recurred, the size of the military more than doubled over the next decade and the percentage of Malays in the military increased from about 60 percent to 80 percent.

The political and economic policies that emerged from two years of emergency rule were shaped by what UMNO leaders saw as the cause of the civil disorder. The Malay leaders felt that the old system had unraveled because of the government’s inability to redress the economic imbalances among the races. Despite the money, attention and effort channeled to Malays, they remained second-class citizens economically, and until that inequity was adjusted, there could never be true racial coexistence. A second problem was the Chinese challenge to the old arrangements, which had first occurred with Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP and continued to exist in opposition parties. Until the Chinese unreservedly accepted the special position of the Malays and until the economic position of the Malays improved, there would be no racial peace. The Malay leadership did not preclude the Chinese and Indians from maintaining their cultural identities. It did not exclude Chinese and Indians from political participation, and it did not prevent the immigrants from prospering, but all rights had to take place in the context of Malay goals.

Prior to 1969, most government efforts to improve Malay living standards had been within a rural context. During this period, the government had not meddled greatly with the export, retail, commercial and manufacturing sectors, which were dominated by foreign and Chinese interests. In reality, the 1969 Malaysian economy was not that different from the colonial economy. British firms still controlled much of the export sector; the retail sector was dominated by the Chinese; and the Malays were primarily involved in the rural and agricultural sectors.

The goals of the New Economic Policy (NEP) were to eliminate poverty and to integrate the economy through a radical restructuring of the nation. Tun Abdul Razak and his advisors had determined that there could never be unity as long as the nation was stratified along traditional racial lines. As long as occupations were determined by race, they felt the Malays would always play secondary roles. The goals of the ensuing Second Malaysia Plan (1971–1975) were as follows:

“The Plan incorporates a two-pronged New Economic Policy for development. The first prong is to reduce and eventually eradicate poverty by raising income levels and increasing employment opportunities for all Malaysians, irrespective of race. The second prong aims at accelerating the process of restructuring Malaysian society to correct economic imbalance, so as to reduce and eventually eliminate the identification of race with economic function. This process involves the modernization of rural life, a rapid and balanced growth of urban activities and the creation of a Malay commercial and industrial community in all categories and at all levels of operation, so that Malays and other indigenous people will become full partners in all respects of the economic life of the nation.”

Thus integration became a massive government effort to bring the Malays into the modern urban economy. The specific goals were that by 1990, the occupations of Malaysians would reflect the racial composition of the country, and by the same year, 30 percent of the country’s corporate share capital would be owned by Bumiputeras. Urbanizing a traditional, rural people in the numbers the government suggested was truly an ambitious goal. Apart from the mind-boggling logistics of this kind of affirmative action program, instilling in rural Malays the competitive values needed to survive in a world of commerce and industry would be a formidable task.

It should be noted that although the government planned to make the percentages of occupations reflect the percentages of the races, the reverse was not true for the agricultural sector – it would remain Malay. The connection between the Malays and the land was a strong symbol in Malaysia. The Bumiputeras were the sons of the soil, and their ownership of much of the land and control of food production went to the heart of their national identity.

A new political reality emerged from the difficulties of 1969 and subsequent emergency rule. A national ideology, which framed the ground rules for the Malaysian political system, was proclaimed. Called Rukunegara, which roughly translates as “the basic principles of the nation,” it contained five basic tenets that all citizens were expected to accept:

• Belief in God

• Loyalty to King and Country

• Upholding the Constitution

• Rule of Law

• Good Behavior and Morality

When parliament reconvened in 1971 to end emergency rule, these principles were incorporated into legislation. The Sedition Act of 1948 was amended to make political use of “sensitive issues” illegal. This amendment took questions of the primacy of the Malay language, the Malay royalty and the special position of the Malays out of the political arena. Any challenge to these issues was treason. The implicit assumption was that the Malays had to accept the participation of the non-Malays in the political life of the country, and this too was a “sensitive issue.”

A new political party system also emerged. Many of the leaders of the 1950s and 1960s were discredited, and a new elite gained power in UMNO, under the guidance of Tun Abdul Razak. The old coalition of “court and kampung,” based on deference and respect for traditional leaders, gradually disappeared. Government programs to uplift the position of the Malays produced a generation of professionals and civil servants whose leadership was based on patronage and access to the new economic system.

Abdul Razak realized that the ruling coalition had to be broadened in the wake of the 1969 riots. As a result, the Alliance Party was replaced with Barisan Nasional (National Front), which was more representative of Malaysia’s political realities. Gerakan, which had wide non-Malay support especially in Penang and Selangor, was brought into the coalition, as was the PPP with its strong base in Perak. For a brief period, PAS was also brought into the ruling coalition, creating a government of true national unity. Several parties from Sabah and Sarawak were included as well, but these parties were in a constant state of flux and were in and out of Barisan on a frequent basis. However, Gerakan and the PPP, along with the MCA and MIC, expanded the ruling party’s influence among the non-Malays in the peninsula.

The primary vehicle for bringing the Malays into the modern economy was the creation of government corporations that would initiate business ventures and offer these opportunities to Malays. The National Corporation (PERNAS) and other organizations offered start-up capital for new companies in transportation, insurance, finance, shipping and manufacturing. The goal was to get these businesses going and then turn them over to Malay owners. The Urban Development Authority (UDA) was established in 1971 to provide an outlet for Malay participation in retail. Its goal was to build and buy shops and offices in predominantly Chinese areas and provide inexpensive entry for Malay small businessmen. MARA and Bank Bumiputera expanded their rural operations to meet more urban, modern needs.

Since Malay ownership of a significant portion of the nation’s corporations was limited by the lack of Malay capital, the National Equity Corporation (PNB) and National Trust Fund (ASN) were set up in 1978 and 1981, respectively. Together with other large investment institutions, they purchased companies in the name of the Malay community. Shares in these ventures were limited to Malays. The PNB and ASN transformed the nature of foreign ownership in Malaysia by buying out the British companies that controlled the mining and plantation sectors – companies such as Dunlop, Sime Darby, Guthrie, Harrisons and Crossfields and the London Tin Company. By buying at fair market value, the Malaysians signaled their commitment to free enterprise and did not scare off other foreign investors. At the same time, Malaysia made a symbolic point by placing these colonial institutions in Malay hands.

In order to produce educated Malays to integrate the professions, entry requirements were eased and additional places reserved for Malays in the country’s universities and technical colleges. All institutions of higher learning were required to conduct most of the instruction in Malay, which improved academic achievement for Malays as well as fulfilling national language goals. By 1977, only 25 percent of the places in tertiary education were occupied by non-Malays. Quotas were also placed on employment in private business ventures to guarantee that Malays would be included at every level, from the factory floor to management. Companies that practiced aggressive Malay hiring were given preference in government contracts, licenses and assistance. Companies were required to provide for Malay ownership participation, with quotas placed on percentages of Bumiputera share holdings. These new guidelines were placed on foreign as well as local investors.

There was irony in the quotas for tertiary institutions, which the government came to recognize in the 1980s and 1990s. While Malays were entering universities in large numbers, because of the quotas, Chinese and Indian parents were forced to send their children to schools in the United States, Australia and Britain. This meant that non-Malays were studying in English at well-established schools. Hence the percentage of immigrant races in law, medicine and similar professions was much greater than their percentage in the general population. As the economy grew and foreign investment poured in, the foreign-educated Chinese and Indians were well-placed to take advantage of the resulting globalization of Malaysia.

The NEP policies had far-reaching consequences. If they had been implemented at the expense of the other races, there would have been serious racial disorder and animosity. The only way the policies would work was if there was sufficient growth, so that Malay participation came about as a result of an ever-expanding economy.

From 1970 to 1990, the economy grew at a dramatic rate. It was aided in part by the injection of large-scale foreign investment, which took advantage of Malaysia’s relatively inexpensive, well-educated work force and investor-friendly policies. The government created industries, and foreign companies provided “Malay” jobs without taking employment away from the other ethnic groups, especially from the working class Chinese. The Chinese unemployment rate actually dropped during this period.

The discovery of new deposits of oil and gas along the eastern coast of the peninsula and offshore Sarawak also contributed to growth. By 1980, Malaysia was exporting some $3.2 billion in petroleum products, 25 percent more than its rubber exports. Malays participated in these new industries through the National Oil Company (PETRONAS).

After Mahathir Mohamad became prime minister in 1981, there was a shift in the emphasis of government policy. Before, large-scale Malay participation in the corporate sector had been through government-owned businesses. As long as the state ran the companies, it was not creating independent businessmen but bureaucrats who ran the companies, hardly a way to prepare Malays to compete with non-Malays. Mahathir wanted to build a powerful group of capitalists in the private sector in the belief that Malay entrepreneurs would help the Malay community as a whole. In order to create these new capitalists, state-run corporations were privatized. The Malaysian International Shipping Corporation, Malaysia Airlines, Edaran Otomobil Nasional, Cement Industries of Malaysia and Syarikat Telecom Malaysia were sold to Malay businessmen. Second, infrastructure projects, such as new highways, water supply, sewerage systems and mass transit projects, were turned over to Malay interests in the private sector. And third, licenses for new television stations, telecommunication services and power were granted to the Malay-controlled private institutions.

These efforts to create greater Malay participation in the private business sector met with mixed results. There is no doubt that Malays occupied a much more important position in the private business sector than they had twenty years previously. Those who seized the opportunities that came their way built highly successful business conglomerates and became giants in the Malaysian corporate world. However, the initiatives also created economic inefficiency. Projects, contracts and licenses were often dispensed without competitive bidding, which meant that political connections became important in obtaining them. Often Malay companies would receive government contracts and then subcontract them to non-Malays or foreign concerns. In 1987, one Malay company with a paid-up capital of only RM2 won the contract for a highway interchange in Kuala Lumpur and then paid a Japanese company to build it. In 1993, another well-connected company won a RM6 billion sewerage contract, which was then built by a British company. In neither case did the Malay company have any construction expertise. The Malay directors of both companies were what economists K.S. Jomo and Edmund Gomez call “political capitalists.” By this, they meant that Malaysia had a rising group of businessmen who were successful as much as a result of their political skills as of their business acumen. For UMNO, this connection was beneficial because it tied the success of this emerging class of Malays to the political fortunes of the party. The withholding of government largesse was also a potent weapon in maintaining party discipline and funds.

Inefficiency was also evident in Chinese and foreign efforts to skirt the spirit of the law. Overemployment resulted when Malays were hired for the sole purpose of meeting quotas. Profits were reduced by bloated work forces that met government rather than market requirements. “Ali Baba” arrangements proliferated. These were business arrangements in which Malays (Ali) held ownership and management positions in Chinese (Baba) ventures but were participants in name only. The Malays were paid, and the Chinese ran the companies.

Another problem of the interventionist policies was that their success was highly dependent on continuous growth. In the recession of the mid-1980s, the shrinking economic pie meant that there were racial winners and losers as a result of the affirmative action programs. Within UMNO, there was increased competition for government-provided contracts and projects. This was one of the reasons for the split within UMNO that challenged Mahathir’s leadership in 1987. The situation also prompted non-Malays in the opposition to express their dissatisfaction with the system. In a crackdown on “dissidents,” scores of politicians were accused of stirring up racial animosities and arrested under the ISA.

Politics in the Borneo states were somewhat more complicated than those in the peninsula. In Sabah and Sarawak, the ethnic communities were fragmented, and in neither state did any one community form a majority of the population. Sarawak was 32 percent Chinese, 31 percent Iban, 23 percent Malay/Melanau and 8 percent Bidayuh. Sabah was 32 percent Kadazandusuns, 30 percent Muslim Bumiputera and 23 percent Chinese. The indigenous people were separated along Muslim and Christian lines. In Sabah, the Kadazandusuns were predominantly Christian, and in Sarawak, there was heavy Christian representation among the Ibans and the Bidayuhs. What this meant was that the chief ministers in these states inevitably came from ethnic and religious minorities, and the Chinese provided the swing vote in determining who would control the state government.

The Borneo states lagged behind the peninsula in terms of education, infrastructure and income levels. This gave the federal government considerable leverage over state politics since aid from Kuala Lumpur was essential to their economic development. Links between the Muslim-dominated central government on the peninsula and the Muslim Bumiputera politicians in Sabah and Sarawak added another dimension to state politics. The political situation in East Malaysia was also influenced by “timber politics.” Both Sabah and Sarawak had vast untapped rain forests. The state governments’ control of logging concessions offered those in power great resources with which to reward influential backers or punish them for their lack of support.

National unity after the May 1969 incident required a tightening of the ties between East and West Malaysia. Part of the motivation for greater unity came from the nature of the Malaysia agreement in 1963. Although the Borneo states contained less than a fifth of the total population, they controlled over a quarter of the seats in parliament. Barisan Nasional needed two-thirds of the seats in order to amend the constitution, and this required the active support of the political parties in Borneo. These parties opposed one another at the state level, but they often sat together at the federal level as members of the ruling coalition. Another reason for bringing the Borneo states into the peninsular political arena was to have more control over them. The eastern states had a greater degree of autonomy and had a separate historical development, which on occasion tended to encourage independent political actions and even talk of secession.

At the time of the formation of Barisan Nasional (BN), the United Sabah National Party (USNO) was included in the coalition. Led by Chief Minister Mustapha Harun, USNO was dominated by Muslim Bumiputeras. Mustapha ruled the state in an alliance with the Sabah Chinese Association. By most accounts, Mustapha’s rule was both authoritarian and corrupt. The central government tolerated this until the mid-1970s, when Mustapha’s support for a Muslim rebellion in the southern Philippines and reports that he was plotting secession led BN to encourage alternative leadership. Donald Stephens, who became Tun Mohammad Fuad when he converted to Islam, joined forces with Datuk Harris Salleh to form an inter-communal party known as Berjaya (Sabah People’s Union). Berjaya swept into power in the 1976 state election and became part of the BN coalition. USNO remained a member of BN until 1984, when it was expelled for opposing the federal takeover of Labuan island.

Mohammad Fuad was killed in an air crash just two months after taking office, and Harris Salleh became chief minister. Berjaya had been brought to power by those who wanted reform and inter-communal power sharing, but the mainly Christian Kadazandusuns and the Chinese in the party became disillusioned with what they saw as pro-Muslim policies and widespread corruption. Joseph Pairin Kitingan, a leading Kadazandusun politician, left Berjaya and, with significant Chinese support, formed Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS, Sabah United Party) in 1985. In the 1985 and 1986 elections, PBS took control of the state government. In 1986, PBS joined Barisan Nasional, but in 1990, it left BN and joined the opposition at the federal level.

The withdrawal of PBS from Barisan Nasional brought about a concerted effort by the latter to regain political control of the state. UMNO established a branch in Sabah to provide leadership for the Muslim Bumiputera community. UMNO’s considerable resources had an immediate impact on the political dynamics of the state. In the run-up to the 1994 state elections, UMNO promised huge amounts of federal developmental aid (the sum total of the programs amounted to an estimated RM1 billion) and a commitment to raise per capita income levels from RM3,500 to RM10,000 within five years. Funds were promised to the Chinese community to upgrade and expand Chinese-language education. It was made clear that this largesse was dependent on Barisan Nasional wresting control of the state from PBS. At the same time, existing aid was cut, which weakened PBS’s ability to provide for economic progress. From 1991 to 1994, the state received low levels of developmental aid, although it was one of the poorest states. Pairin was charged and convicted of corruption, while his brother, Jeffrey, was arrested under the ISA for plotting secession.

Barisan Nasional’s efforts paid off when Yong Tock Lee led a number of Chinese out of PBS and established a new party, the Sabah Progressive Party (SAPP), which was quickly admitted into BN. In spite of this, PBS won a narrow victory in the state election of 1994 by playing on ethnic loyalties and mistrust of the central government in Kuala Lumpur, but it was evident that its days were numbered. UMNO had won 19 of the 48 seats in the assembly, and SAPP had secured three. In the weeks after the election, there was a large defection from PBS. Three new parties were established, and all were admitted into BN. Adding insult to injury, Pairin’s brother, who had been released from detention, also left PBS and joined BN. When the smoke cleared, Barisan Nasional ruled the state, and PBS had only seven seats in the assembly.

After the 1969 political realignment in Malaysia, the government in Sarawak was led by Tun Abdul Rahman Yakub, the head of Parti Bumiputera (PB). This party represented the Malay/Melanau community and maintained power in part because of its close ties with Kuala Lumpur. There was significant opposition from the Sarawak United People’s Party (SUPP), which was mainly Chinese with some Iban support, and the Sarawak National Party (SNAP), which was mainly Iban with some Chinese participation. The central government was able to exert enough pressure on PB and SUPP to form a coalition at the state level. In 1973, PB merged with a non-Muslim indigenous party, Pesaka, to form Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB). In 1976, SNAP was brought into the coalition, and the group of parties – PBB, SUPP and SNAP – became popularly known as Barisan Tiga (three). In 1981, Abdul Taib Mahmud, who had represented PBB at the federal level, took over as chief minister from his uncle, Tun Abdul Rahman.

In 1983, there was a split in SNAP when Leo Moggie and a group of young Ibans formed Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak (PBDS). It became part of Barisan Nasional at the national level but was in opposition at the state level. The formation of PBDS reflected a view in the Iban community that Barisan Tiga neglected the needs of the non-Muslim indigenous people. In their eyes, the bulk of the government’s developmental programs was directed at the towns and coastal areas, where the Muslim Bumiputeras and the Chinese benefited from them. Income levels and literacy rates among the Ibans and other interior ethnic groups were much lower than the state average. PBDS felt that a united “Dayak” community could do better outside the Barisan Nasional state coalition, but it could not crack Barisan Tiga’s hold on power. In 1994, it accepted the inevitable and returned to the BN fold.

On a larger scale, the first national election contested by Barisan Nasional in 1974 was a smashing success. The party polled over 60 percent of the vote and won a two-thirds majority in the federal parliament. In the peninsula, it won 104 of the 114 possible seats. At the state level, it formed the governments in all the peninsular states with two-thirds majorities. The election represented national unity and hope for the future of interracial cooperation within the Malaysian context.

Tun Abdul Razak played a key role in helping Malaysia recover from the trauma of the 1969 riots. He understood the frustrations of the emerging generation of Malays who wanted more economic opportunities. By including younger voices from outside UMNO’s traditional pool of leadership in the decision making process, Abdul Razak was able to act as a moderating influence on their views and actions. His ability to reach out to diverse opinions was an important legacy during this emotionally charged time in Malaysian history.

The old UMNO guard did not give up without a fight. When Abdul Razak died in January 1976, they pounced on his protégés. Acting on the “advice” of Singapore’s Special Branch, Ghazali Shafie, the minister of home affairs, accused a number of Abdul Razak’s advisors, such as Abdul Samad Ismail and Abdullah Ahmad, of sympathizing with the communist cause and detained them under the ISA. It is amazing how quickly these men were “rehabilitated” when their leader, Mahathir Mohamad, took over as prime minister in 1981, and they were once again given responsible positions – they must have felt like political yo-yos.

Dato Hussein Onn succeeded Tun Razak as prime minister. In many ways, Hussein was viewed as a caretaker leader, while the factions within the party fought for supremacy. As the son of Onn Bin Ja’afar, the original founder of UMNO, Hussein had impeccable credentials in the eyes of the old guard; among the newer leaders, he was acceptable because his poor health would mean a relatively short tenure.

Hussein ruled in the moderate conciliatory style that was characteristic of Malaysia’s first two prime ministers. He led BN into the 1978 election, and once again, the party showed its dominance. It won 131 of the 154 seats contested nationwide and 57 percent of the popular vote. Although this was marginally lower compared to the 1974 election, it was still impressive.

Two enduring opposition parties emerged from this election – PAS and the DAP. The former had entered the ruling coalition after the 1969–1971 debacle but was unable to coexist successfully in the Barisan Nasional fold. It left BN in 1977. The next year it won five seats in parliament and captured about a third of the total Malay vote. The DAP enhanced its status as the primary non-Malay voice of opposition in 1978 when it increased its representation in parliament to sixteen seats, polling close to half of the total non-Malay vote. In the past, opposition parties had risen and fallen – Socialist Front, Labor Front, Independence of Malaya Party and PPP – but these two were more permanent.

The existence of two well-organized opposition parties with solid bases of support forced moderation and cooperation on the parties within Barisan Nasional. When elections were held, no amount of fiddling of electoral boundaries could change the challenge from the DAP on the left and PAS on the right. If BN moved to allay the extreme voices in the Malay community, the DAP attacked its base among non-Malays, and if BN moved too far to accommodate non-Malay demands, PAS was waiting in the wings to grab the Malay vote. The problem for the opposition was that neither party could individually challenge BN’s control of the government, nor could they cooperate to bring it down. Outside their joint desire for greater democracy, the political views of the DAP and PAS were ideological oil and water. Their continued presence, however, acted as a check on Barisan Nasional, forcing the components within it to find common ground and take a moderate course.

The fact that PAS and the DAP offset each other maintained BN’s two-thirds majority in parliament. This majority gave the ruling party the ability to amend the constitution at will, and as long as this condition existed, parliament and the party controlling it had few checks on their power. Loss of this power would change the political dynamics of the country. For example, if the constitution were to become more of a set document and not open to constant tinkering, interpreting its meaning would move from parliament to the courts. Judicial review would take on greater importance, and the ruling party would no longer be able to change the constitution to meet the political demands of the day.

The presence of a competitive party system forced BN to be responsive to the needs and aspirations of Malaysia’s multiracial electorate. This did not mean there was liberal democracy in the Western sense. There were serious limitations on the ability of the opposition to compete, and there were few checks and balances on the ruling party.

The media generally reflected the views of the ruling coalition. To the casual observer, a Malaysian news-stand indicated a competitive newspaper industry with a variety of publications in the three major languages. If the observer dug deeper, she or he discovered that the print media was owned by parties within the ruling coalition or interests closely aligned with them. For example, the largest English, Malay and Chinese newspapers were owned by the Fleet Group, an investment arm of UMNO. The Star, the second largest English-language newspaper, was owned by business interests aligned with the MCA, and the Tamil press was controlled by supporters of the MIC. Criticism of the government in print was a rare phenomenon. Each periodical had to obtain a license to publish each year from the government, and it would not have been issued if the periodical aggravated “national sensitivities” or failed to serve the “national interests.” Restrictions even went so far as to include being on the wrong side of a conflict within the ruling coalition. For example, The Star was shut down for a while in 1987 because of a column written by the Tunku that was critical of Prime Minister Mahathir and his supporters.

The broadcast media was tightly regulated as well. Radio and television spoke for the government and spent a considerable amount of time covering BN achievements. The lead news stories on Malaysian television were always about the prime minister. There were a few privately owned stations, but they and the Astro satellite station tended to toe the party line and practice self-censorship as well.

The Internal Security Act and the Sedition Act enhanced the powers of the government to define the parameters of political debate in Malaysia. This was especially true in the aftermath of the 1969 riots and the decade or so following them. Between 1960 and 1981, over three thousand people were detained without trial for acting “in any manner prejudicial to the security of Malaysia ... or to the maintenance of essential services therein or to the economic life thereof.” DAP leader, Lim Kit Siang, saw the inside of Malaysia’s jails three times under this law, as did other DAP members. The use of these laws extended to those who challenged the pro-Malay communal nature of the government, to trade union leaders, such as the head of a union who led a strike against Malaysia Airlines in 1978, and even to members of the ruling coalition, such as in 1987 when UMNO and MCA activists were detained for stirring up racial sensitivities.

The five decades of UMNO’s existence reflected an important dimension of Malaysian democracy – its diverse and participatory nature. Many of the safeguards of individual freedom that exist in the Western model of democracy were weak in Malaysia, but the nature of UMNO and the ruling coalition placed checks on the political leaders and offered opportunities for Malaysian citizens to be part of a democratic dialogue. UMNO, like the other component parties of Barisan Nasional, was a grassroots party. It had a party membership of over three million people organized at the branch, division, state and national levels. Delegates from grassroots branches had voices in determining party leaders and the general direction of the party. The annual UMNO general assembly was not unlike an American political party convention, and on occasion had spirited and competitive contests for party leadership positions. Party policy was often debated openly and frankly. Like any party in a democracy, the amount of division and debate depended on the ability of the leadership to show direction and forge compromise. It fostered the meaningful participation of Malaysian citizens in the process of governing.

In the 1970s and 1980s, winds of change blew through UMNO, and no one represented this more than the man who took over after Dato Hussein Onn’s resignation in 1981 – Dr. Mahathir Mohamad. He was the first Malaysian prime minister to come from outside the traditional aristocracy. He was a commoner from Kedah, and his medical qualifications were from the University of Malaya, not from Britain.

Although he had been in UMNO since 1946 and was 56 years old when he became prime minister, Mahthir was in tune with the younger ascendant capitalist Malays. He was in the vanguard of a group that was fiercely critical of the style and methods of the generation that had led UMNO for thirty-five years. His criticism of the Tunku’s conciliatory attitude toward non-Malays after the May 1969 incident had resulted in his expulsion from the party, and his 1970 book, The Malay Dilemma, was banned. The book, in many ways his manifesto, was a scathing attack on the British colonial legacy, Malay values and the inability of the Malay leadership to improve the economic status of Malays.

Many underestimated Mahathir. After Tun Abdul Razak brought him back into the BN fold in 1971 and made him minister of education, his rise was meteoric. Within ten years, he became prime minister, largely because of his ability to articulate the economic aspirations of a generation of Malays who had become much more assertive after the May 1969 events, as well as due to the success of the NEP. To the older generation, Mahathir’s confrontational style and impatience were almost “unMalay,” but his outspoken manner reflected the views of the ascendant generation, which felt that Malays had to discard the self-effacing, non-confrontational values that held them back in the modern world. His “we’re not going to take it anymore” attitude went down well with many Malays. Singapore, Western leaders, the royalty and Malay traditionalists were all fair game.

Much of the change in the Malay political community that brought Mahathir to power can be traced to the incredible growth of the public sector in the 1970s and 1980s as a result of the NEP. The size and scope of the programs introduced to benefit the Malay community enlarged the government to the point where, by the mid-1980s, about a third of Malaysia’s national income was generated by government spending.

Attempts to bring the Malays into the modern sector of the economy created a larger Malay middle class. Some succeeded as a result of the explosion of civil service jobs that came with all the new agencies and programs. Others prospered as part of a growing Malay business community whose success was often tied to government funding and racial preference. What they had in common was that most had risen from humble rural backgrounds and did not belong to the traditional Malay economic and political elite.

Another change that Mahathir sought was to reduce the power and influence of Malay royalty. The sultans had been powerful racial and political symbols of Malay rule in the face of an assertive immigrant population. In the run-up to independence and the first couple of decades thereafter, the sultans had been allies of UMNO, and their families had great influence within the party, but by the 1980s, Malay royalty had begun to lose the loyalty of the political establishment. On several occasions, the sultans angered UMNO by meddling in the appointment of elected officials or by supporting the opposition. They seemed to be anachronistic, feudal symbols in a modernizing world. As Malay numbers grew as a percentage of the overall population, the need for symbols decreased conversely. The increased mobility of the Malays from kampungs to cities and from state to state also weakened the ties between the palace and the people. Political loyalties were more to a party and an active government than to royalty.

In the first decade after independence, Malay business activities tended to be controlled by members of the traditional aristocracy, who parlayed their political connections into choice business deals. A royal title on the board of directors and a word in the right ear opened doors and facilitated government action. As a new class of businessmen from common backgrounds arose, the aristocracy, with its political connections and status, hindered their ability to succeed.

Mahathir made his first move against the royalty in 1983–1984 by proposing a constitutional amendment that would eliminate the powers of the king and sultans to delay legislation and declare a state of emergency. Some objected to this because the power would then be transferred to the prime minister. Others felt the move was too soon because many Malays still had close ties with and affection for their sultans. As a result the powers of the sultans at the state level did not change, but Mahathir did manage to end the king’s right to delay the legislative process at the national level.

In the early 1990s, UMNO made a further assault on royal power. This time the leaders were better prepared. In a well-orchestrated campaign, politicians and the media began saying publicly what had previously only been mentioned in private – that some of the royal families abused their positions. Stories began to appear in the press about royal Christmas parties where liquor flowed freely and about royal princes who committed crimes and were not punished. These tales of expensive cars and lavish lifestyles at public expense began to chip away at the credibility of the royal families. Their government privileges were withdrawn and legislation ended their legal immunity.

The controversy over the role and powers of the sultans was confusing to many Malays. Constitutionally, the sultans are identified as the protectors of the Malay special position, but how could they protect without any power? In theory, the sultans are sovereigns of their states, but what happened to that concept when royalty could be dragged into court like any other citizen? One suspects that the bottom line for the politicians who wanted change was that they believed that UMNO was the rightful protector of the Malay special position and thus wanted to solidify its political control of the Malay community. No other modern country had anything resembling this Malaysian system of nine royal families, and their somewhat awkward roles were just another of the dilemmas facing Malaysia as it dealt with the realities of the modern and postmodern world.

There was an interesting role reversal that took place in the battles over the power of royalty. What Mahathir and UMNO leaders were saying would have been considered sedition if vocalized by an opposition politician, especially if he was non-Malay. The rights and privileges of the sultans were one of the “sensitive issues” covered by the Sedition Act of 1971. On the other hand, there were non-Malay leaders and members of the judiciary, including Lim Kit Siang of the DAP, who actually defended the powers of Malay royalty as necessary checks on the power of the elected executive.

The attack on royal privilege was only part of Mahathir’s political agenda in the strengthening of central executive power in the hands of BN. In the late 1980s, he moved to clip the wings of the relatively independent judiciary. Mahathir felt that the judiciary was not meant to interpret the laws, merely to enforce them. Determining whether government actions and legislation were constitutional lay with parliament, not with the courts. In parliament in 1987, Mahathir said that “if judicial review persists, the government is no longer the executive. Another group has taken over its role.”

A series of court cases that went against the government and a crisis in the ruling party brought matters to a head. In 1986, the government revoked the work permits of two American journalists. On appeal, the Supreme Court overruled the government because the journalists had not been allowed to defend their cases, a violation of natural justice. In another case, a Supreme Court justice overturned the internment under the ISA of an opposition politician, the DAP’s Karpal Singh. In yet another case, the high court agreed to an injunction against the awarding of a contract to an UMNO-related company in an action brought by opposition politicians. These three cases reinforced Mahathir’s view that the judiciary was thwarting the will of the executive.

A battle for the leadership of UMNO also drew the courts and the politicians into conflict. In April 1987, Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, supported by Datuk Musa Hitam, challenged Mahathir for the presidency of UMNO, which in effect meant challenging him for the position of prime minister. At the party’s national conference, the vote was 761 to 718 in Mahathir’s favor. The fight then went to the courts. Razaleigh’s faction sued, claiming that illegal party branches had voted. As a result, the court ruled that UMNO was an illegal organization. Mahathir’s opponents appealed to the courts to call for new party elections without the illegal branches. Lord President of the Supreme Court Tun Salleh Abas scheduled the appeal to be heard by all nine Supreme Court judges, a unique occurrence in Malaysia. Mahathir’s political fate was in the hands of the very men he had been criticizing. He struck back by prevailing on the king to suspend Salleh and to set up a tribunal to try him for undermining government authority. Salleh appealed to the Supreme Court on the grounds that the tribunal was illegal, and five members of the court issued a stay. All five were then suspended and another tribunal set up to investigate them. In the end, Salleh and two other judges were removed from the court, and the party’s election results remained in Mahathir’s favor. A strong message had been sent as to how independent the Malaysian judiciary could be.

The New Economic Policy that emerged after the racial confrontations of 1969 and 1970 was meant to radically change Malaysian society and its economy. There is no doubt that the Malaysia that emerged in the 1990s was very much different from the one that had produced the riots of 1969. Huge foreign investments and massive government intervention in the 1970s and 1980s created a country that was recognized as one of Asia’s emerging “tiger cub” economies. Malaysia changed fundamentally from an economy that reflected its colonial role as an exporter of raw materials and an importer of manufactured goods to that of a diversified newly industrializing country (NIC). The days of mentioning Malaysia and immediately thinking of rubber and tin were long gone.

Between 1970 and 1990, the average growth of the Malaysian economy was close to 7 percent a year; in the 1990s, it increased to over 8 percent. While the country as a whole grew by leaps and bounds, manufacturing and commerce just about doubled and accounted for close to half of the nation’s wealth. By 1990, manufacturing alone made up 27 percent of the Malaysian economy, and even more indicative of the change, it made up 61 percent of the nation’s exports. Even with the discovery of new deposits of oil, Malaysia had become more dependent on worldwide demand for computer chips, cellular telephones and air conditioners than on oil, rubber and tin.

The ownership of the economy also went through a transformation. By 1990, foreign ownership of corporate assets had fallen from around 60 percent to 25 percent. The Malay share of ownership had risen from some 2 percent to over 20 percent. Forty-six percent of this was in the hands of individual Malays, while the rest was held by government trusts and funds.

An irony was that after twenty years of affirmative action and pro-Malay government policies, the Chinese had almost doubled their share of ownership. A case can be made that the inclusion of Malays as more active participants in the modern economy had not come at the expense of the immigrant communities. High tides had raised all the boats this time, at least in the realm of shareholdings.

National growth led to higher incomes for most Malaysians. Household incomes during this twenty-year period increased threefold, and the number of people living on incomes below the poverty line dropped from 49 percent in 1970 to 15 percent in 1990. In the 1990s, with increased growth rates, these improved at an even faster rate. By the mid-1990s, the reduction of unemployment and poverty had become one of the key achievements of the BN government.

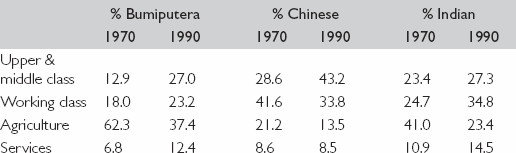

Table 16.1: Class Composition of Communities in Malaysia in 1970 and 1990

Crouch, Harold, Government & Society in Malaysia, p. 185

From the figures in Table 16.1, a number of generalizations can be made about the financial and sociological differences in the Malaysian population in 1990, which changed significantly between 1970 and 1990. Malays moved from stereotypical farmers/fishermen to occupations that were much more varied and open to economic opportunity. The new occupations meant that Malays had moved out of the rural areas into the towns and cities to the point that almost half lived in urban areas. This was a far cry from 1957, when 75 percent of the Malay population was rural and involved in traditional pursuits. However, these statistics should be qualified because farming was still very much a Malay occupation in Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah and Perlis in 1990, and those Malays had incomes lower than Bumiputera in the rest of the country.

The economic transformation of Malaysia over the first twenty years of the NEP was phenomenal, especially for the Malays. As income levels rose and Malays became more urban and less involved in agriculture, the changes brought into question some of the underlying assumptions of Malaysian life. Chief among them was what it meant to be a Malay.

A study of Malaysian history shows that the Malays are a mixture of people from all over the archipelago – Bugis, Acehnese, Minangkabau, Javanese and others. When these people came together, what gave them a common identity, both legally and socially? The conventional definition is that a person is Malay if he or she habitually speaks Malay, is a Muslim, is born in Malaysia and follows Malay customs. Anyone can speak Malay and become a Muslim, thus the most important trait is to act like a Malay.

The problem for the Malays was that their value system and behavioral expectations had deep roots in a rural kampung lifestyle. The move from the village to the city is a familiar one in history, whether it is in the United States, Japan or Thailand. All who make this transition face serious challenges to their value systems. Traditional values are not particularly conducive to success in the city. In the competitive atmosphere of a capitalist economy, values of cooperation and coexistence become increasingly irrelevant. The ability of the individual to compete becomes more important than relationships with neighbors. Status is determined by wealth and possessions rather than manners, respect for elders or the other group-oriented values that determine stature in the kampung.

As the Malays became urbanized, they were exposed to these diverse influences. The places in which they worked and lived were not homogeneous entities that provided the security of a community with shared values and predictable expectations. The Chinese and Indians became part of their communities, and their children went to the same schools. Urban life also exposed the Malays to foreign influence. Movies, advertising, nightlife, videos and shopping malls all bombarded the Malays with materialistic values geared to the individual.

It is interesting that Malay values were viewed as impediments to Malay economic success. From colonial administrators down to Prime Minister Mahathir, the Malays’ poor economic position was attributed to their lack of drive, deference to authority and live-and-let-live attitude. In the eyes of many observers, the immigrants outstripped the Malays because their values were geared toward a modern capitalist economy. Thus, for the Malays to prosper outside the traditional village context, they had to give up many of their traditional Southeast Asian values and adopt new ones, another irony in the argument over Asian versus Western values that took place in the 1990s.

The movement of the Malays from the farm into the modern economy was not evolutionary, as it was in many societies, but government driven, and it took place in the space of one generation. What did individual Malays find to fill the void left by the weakening of some of their core values? A car and a house are poor substitutes for a close-knit community. It was a strange new world for many young Malays who moved from poor farms to universities and then to office buildings. To the Malay community as a whole, unity of purpose was key to political dominance. The fundamental assumption of the Malaysian political system developed by the Alliance and Barisan Nasional was that people voted along communal lines. As people moved into the cities, this complicated UMNO’s political fortunes. How would the process of modernity affect Malaysia’s racial political formula?

For many Malays the answer to the void caused by change was commitment to and interest in Islam, which offered a familiar safe haven. On university campuses, Muslim renewal groups and youth organizations grew at an impressive rate. Organizations, such as ABIM (Islamic Youth Movement of Malaysia) led by Anwar Ibrahim, reflected the aspirations of many. ABIM called for greater Islamic principles in governing, including an Islamic bank, an Islamic university and a more Islamic foreign policy. Along with this, though, was a message of social welfare. They decried continuing rural Malay poverty and were critical of the unequal distribution of wealth among the Malays. They called this message, progressive Islam.

ABIM was symptomatic of what was known as the dakwah (revivalist) movement. The social change brought by the changing economy had inspired in many a closer relationship with their religion. This could be superficially seen by the tremendous increase in the number of women wearing the tudong (head scarf) and increased mosque attendance and pilgrims going on the Hajj. These actions indicated the fact that for many Malays the answer to the challenge of modernity was to embrace Islam more tightly.

This Islamic revival was actively encouraged by the government, especially by Mahathir. In the 1990s, a host of government programs and activities tried to make Islam a unifying force in the Malay community. Islamic civilization was taught in schools; the government actively encouraged and supported those who wished to go on the Hajj. An Islamic university was established. There was strong government support for Muslim youth and cultural groups, as well as government legislation that enforced Islamic laws against alcohol and unacceptable sexual relationships, such as khalwat. (In essence, khalwat refers to improper physical relationships between members of the opposite sex. Depending on how strictly it is defined, it may include everything from holding hands in public to adultery.)

The Islamic resurgence among Malays had wide implications for society as a whole. Malaysia was not immune to the forces blowing through the greater Islamic world in the wake of events in Iran, Afghanistan and other parts of the Middle East. The competing visions of how Islam should deal with the modern world found willing listeners in Malaysia. The clashes between the traditional and the modern and between the fundamentalist and the progressive in Islam would also have tremendous ramifications for the approximately 40 percent of Malaysians who were not Muslim.

UMNO took measures to co-opt the Islamic surge and steer a moderate course. Politically this had interesting repercussions. UMNO’s move to embrace and encourage the role of Islam in the community left PAS, which had been calling for the imposition of Islamic law for some time, in a quandary. As UMNO moved to improve its Islamic credentials, where did that leave PAS? The answer was to move to the fundamentalist right.

Thus the government and UMNO walked a fine line. Islam eased social change and maintained Malay unity, but the more extreme religious zealots were a perceived danger to the country. To this end, the government became the arbitrator of what was and was not acceptable Muslim behavior and doctrine. A number of groups, such as Al Arqam, which had called for the establishment of urban communes and cooperative business ventures, were branded as deviationist and banned, and their leaders were arrested. The Al Arqam leader claimed he was arrested not for his religious views but because his movement clashed with the UMNO view of how urban Malays should think and act.

One of Mahathir’s strong points was the courage with which he spoke out against the excesses and narrow-mindedness of fundamentalism and campaigned for Muslims to be more pragmatic, open-minded and liberal in their understanding of Islam. This included being more tolerant of other faiths. He set up IKIM (Institute for the Propagation of Islamic Understanding), which examined current issues from an Islamic perspective and encouraged dialogue with other faiths. Ironically, a case could be made that by the government trying to define and direct Islam, this actually drew religion into politics as never before in Malaysia. Future events would prove that Mahathir had opened a proverbial “can of worms.”

Another effect of the social change was a serious drug problem in Malaysia. Islam helped many deal with the social dislocation, but a minority reacted to the change with anti-social behavior, especially in abusing drugs. Estimates of the number of addicts in Malaysia ran in the hundreds of thousands, big numbers for a country of then twenty million people. They were especially striking in the face of the stringent drug laws, which included mandatory death penalties for trafficking or possessing relatively small quantities of drugs. Malaysia executed more people per capita than almost any democracy in the world. Most of the executions were for drug offenses, and yet the problem continued to plague the country.

Further evidence of how social change had affected Malaysia’s young was contained in a 1994 government survey of urban youth between the ages of thirteen and twenty-one. In the group interviewed, 71 percent smoked, 40 percent watched pornographic videos, 28 percent gambled, 25 percent drank alcohol and 14 percent took hard drugs. In the United States, these numbers would not have been quite as shocking, but in Malaysia, they were disturbing.

In many ways, Penang and Singapore are alike, although one is a sovereign country and the other a state. They share a similar colonial history in the Straits Settlements, and at the time of independence, both were economically dependent on their ports and ties to Malaya’s production of raw materials. The two cities share the problems of being Chinese islands in a Malay ocean and have been ruled by predominantly Chinese parties.

Their paths diverged in 1965 – Singapore going it alone because of its confrontation with the Malay leadership in Kuala Lumpur, while Penang’s political leadership followed a path of accommodation by participating first in the Alliance and then as part of Barisan Nasional. Since 1965, both have experienced rapid economic growth. In this respect, Singapore’s experience has been much more impressive, with personal income figures twice those of Penang. The latter, however, has not done badly. It has diversified its economy into manufacturing and tourism and has full employment. The people of Penang enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the country.

When the government moved to make Malay the language of instruction, many of the schools in Penang found ways to offer extended instruction in English. This carried on its legacy as an English-language center and contributed to the city’s becoming an electronics hub.

While Penang has not prospered as much as Singapore, it has successfully maintained its Chinese identity. Chinese clan, dialect and occupational organizations continue to play important roles in preserving traditional Chinese culture. The ceremonial core of Chinese ideology is still an important part of life in the Penang community, while in Singapore, physical redevelopment of the island has weakened it. Some academics claim that if you want to see traditional Chinese culture in a modern context, visit Penang.

Rent control had an impact on Penang similar to that in Singapore in creating a sadly rundown city center. But rent control also preserved the old buildings, and since it has been lifted, a rejuvenation has taken place.The efforts by the government and people to preserve and renovate the old buildings are producing a magnificent collection of colonial architecture serving many of the housing, government and business functions it did a century ago.

How is it then that Penang, which had to deal with a Malay/Muslim central government, has been able to preserve so much? One reason is the existence of a relatively competitive democracy on the island. The political leaders of the state must stand up for Chinese rights or face problems at the polls. In the 1960s, when the MCA did not appear to be digging in hard enough to protect Chinese interests, Gerakan defeated the MCA candidates. In the 1980s and 1990s, when the MCA and Gerakan joined BN, the DAP challenged BN to protect Chinese interests. In the 1986 and 1990 elections, the DAP posed a serious threat to BN power in the state, and Malay federal leaders had to step in to assure Penang voters that the central government planned to respect their language and culture.

A second probable reason is that, because of their minority position in the country politically and numerically, the Chinese in Penang held on tighter to their traditional ways. Language and culture became powerful symbols of unity in the face of perceived attempts by the Malay leadership to dilute the Chinese identity. Whether the immigrant races should cling to their separate ways of life is a different issue altogether, but Penang has had some success so far.