Introduction

On the other hand, I have sufficiently strong nerves and a sufficiently strong sense of duty . . . that if I consider something to be necessary then I will carry it out uncompromisingly. I did not consider myself justified—I’m referring here to the Jewish women and children—in allowing avengers to grow up in the shape of the children who will then murder our fathers and grandchildren. I would have considered that a cowardly thing to do. As a result the question was solved uncompromisingly.

HEINRICH HIMMLER, speech to German generals, May 24, 19441

They were crammed in so tightly against one another that the smallest and weakest were inevitably suffocated. At a certain moment, under that pressure, that anguish, you become selfish and there’s only one thing you can think of: how to save yourself. That was the effect the gas had. The sight that lay before us when we opened the door was terrible; nobody can even imagine what it was like.

Auschwitz Sonderkommando member SCHLOMO VENEZIA2

Sometime in the late summer to early fall of 1941, Hitler decided to solve the so-called Jewish Question through the physical extermination of the Jews of Europe. This decision set in motion a period of intense preparation and activity that ended in the of murder extraordinary numbers of Jews in a short period of time . . . and which would place Schlomo Venezia in a place of unimaginable horror: this “Final Solution” completed the evolution of the Nazi state into a genocidal one. In the spring of 1942, 75–80 percent of the victims of the Holocaust were still alive and 20–25 percent had already been murdered. Eleven months later, these percentages had been reversed.3 This was Himmler’s uncompromising solution that he referred to in 1944.

This was the Holocaust of the gas chambers, the crematoriums, and train journeys to annihilation. While mass shootings continued, this more “industrial” form of killing became, for a time, the primary method of murdering Jews and the most deadly. This chapter explains how this program of mass murder developed and was carried out. It will briefly examine earlier plans for solving the “Jewish Problem,” before discussing the timing of the decision for murder and the planning involved in creating a system capable of murdering millions relatively quickly and efficiently. We will also examine the operation of some of these killing centers. As part of this discussion, we will focus on the extermination center of Treblinka. We will close with an exploration of the final liquidations of ghettos and the closing of most of the extermination centers.

The Evolution of the Final Solution

Today I will again be a prophet and say, if international finance Jewry in and outside Europe succeeds in plunging nations into another world war, then the end result will not be the Bolshevization of the planet and thus the victory of the Jews—it will be the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.

ADOLF HITLER to the Reichstag, January 30, 19394

As we have begun to see already in this book, the movement from discriminatory policies against Jews to their physical extermination was more evolutionary than preordained. However, few topics have created more intense debate about the Holocaust than the nature and timing of the plan to murder all the Jews in Europe (and really the world). In 1939, when Hitler made his prophecy above, it was still unclear what the “annihilation of the Jewish race” meant to him and others in the regime. Therefore, it is important to examine in some depth how this decision came about . . . and how we can deduce that timing. The “twisted path” leading to the gas chambers resulted from a combination of innovation, experimentation, and previous experience; it was also modified both at the ground level and in the upper echelons of the Nazi system. In short, it demonstrates how an incredibly diverse group of people worked together to create a system to murder other human beings.

There are, of course, those who contend that Hitler intended to murder the Jews from the very beginning. Hitler did write in Mein Kampf in 1925, “If, at the beginning of the War and during the War, twelve or fifteen thousand of these Hebraic corrupters of the nation had been subjected to poison gas . . . then the sacrifice of millions at the front would not have been in vain.”5 However, to read into this statement a concrete plan to murder Jews in the future is foolish. Hitler refers to the stab-in-the-back myth and the false assumption that Jews did not fight in proportional numbers during World War I. (They did.) He is not laying out a step by plan that ends in the gas chambers. Hitler does expound upon antisemitic theories but only once (above) suggests the killing of Jews.

For these and other reasons, it is unlikely that Hitler entered office in 1933 with the intention of murdering all Jews. The policy developed through a process of “cumulative radicalization,” in which ever more severe and extreme measures were favored by Hitler and Himmler. This explanation also fits well with the concept of “working toward the Führer,” where Hitler gave vague guidance and then encouraged those who brought him plans that moved in the direction he wanted. He himself acknowledged this, saying he relied on “tough people of whom I know they take the steps I would take myself. The best man is for me the one who bothers me least by taking upon himself 95 out of 100 decisions.”6 Even the future chief architect of the Final Solution, Reinhard Heydrich, stated in the summer of 1940 regarding the Jews: “Biological extermination is undignified for the German people as a civilized nation.”7

In addition to Hitler’s leadership style and the habits of his subordinates, very real alternate plans demonstrate that the murder of the Jews culminated from a long process influenced by both situation and ideology. The first solution was the Lublin/Nisko plan in which Jews would be deported and concentrated on a reservation in Poland. As we have seen, this plan failed due to objections from local Nazi leaders as well as logistical difficulties. The second major plan was the Madagascar Plan, to deport the Jews of Europe to the island off the east coast of Africa. With the fall of France, this territory became available to the Germans. Far from being a fantasy, the Madagascar Plan attracted very real attention in the summer of 1940. Franz Rademacher, head of the Jewish Desk (Section D-III) in the German Foreign Office, personally took up the planning with great zeal. Hitler himself informed the chief of the German Navy that he intended to resettle European Jews there.8 Even ghetto Chairman Adam Czerniakow in Warsaw was told that his Jews would be resettled to the African island. As one historian has written, there can be “no doubt that during this period both Rademacher and Eichmann tackled the [Madagascar] plan in full earnest.”9 While the Madagascar plan remained a territorial one, the displacement of millions of Jews to the rugged island would clearly lead to a decimation of the population that was not viewed unfavorably. In the end, however, the circumstances of war meant that the plan was scrapped. The failure to defeat Britain left it in control of the oceans, making any deportations from Europe impossible.

The final territorial solution proposed for dealing with the “Jewish Question” appeared in 1941 and involved the deportation of Jews to a “territory yet to be determined.” This was the soon to-be-occupied Soviet Union, potentially beyond the Ural Mountains, into Siberia and Asian Russia. This plan, which also unapologetically acknowledged high mortality rates, remained undeveloped as events of the war soon overtook it.

I hereby charge you with making all necessary preparations in regard to organizational and financial matters for bringing about a complete solution of the Jewish question in the German sphere of influence in Europe.

REICHSMARSCHALL GÖRING to Reinhard Heydrich, July 31, 194110

It was in the context of the invasion of the Soviet Union and the massive demographic engineering already planned that, sometime in the late summer or early fall of 1941, Hitler decided that Europe’s Jews should be murdered rather than resettled.11 First, it should be made clear that the reason the timing is not conclusively known is that unlike the “euthanasia” program, no written order from Hitler exists for the Final Solution . . . and likely never did. Rather, he informed his high-ranking subordinates of his decision and they began to carry it out. The closest evidence to a direct order is the above memo giving Reinhard Heydrich the freedom to prepare for the Final Solution. Thus, historians must track the decision for the murder of the Jews through Nazi actions taken across Europe and the changes in policy.

With the war in the East going relatively well, it seems that Hitler abandoned his previous plans to delay implementing any permanent Jewish policy until the end of the war. This decision’s repercussions gradually emerged throughout 1941 and into 1942. The events that heralded the coming of the Final Solution are scattered geographically and temporally, but they can be placed in a clear historical context. At the upper levels of the Nazi bureaucracy, Göring signed Heydrich’s July 31, 1941 order:

Complementing the task that was assigned to you on 24 January 1939, which dealt with arriving at-through furtherance of emigration and evacuation-a solution of the Jewish problem, as advantageously as possible, I hereby charge you with making all necessary preparations in regard to organizational and financial matters for bringing about a complete solution of the Jewish question in the German sphere of influence in Europe.12

This order (drafted by Heydrich himself) represented nothing less than an authorization for Heydrich (and the SS) to oversee all the necessary requirements for a physical solution to the “Jewish Question.” With this mandate, Heydrich began planning an entirely different system of mass murder. At the same time, anti-Jewish actions in the Soviet Union began to change as well. In Chapter 6, we saw that the Einsatzgruppen were initially tasked with killing military-aged male Jews and communist functionaries (which Heydrich reiterated in a July 2 memorandum). However, we also saw that this directive expanded quickly via verbal orders from Himmler and other high-ranking SS officials so that, by September, the Einsatzgruppen—reinforced by additional Police Battalions, local auxiliaries, and the Wehrmacht—were systematically murdering Jews of all ages and sexes. This shift in targeting and scale also signaled that something had changed in Nazi policy toward Jews. Elsewhere in Nazi territory, it appears that others sensed change in the air. The head of the resettlement office in Poznań, Poland, wrote Eichmann on July 16, expressing concern about the food situation in Łodz´ and asking if “the most humanitarian solution would not be to finish off those Jews who are unfit for work by some expedient means [emphasis mine].”13 In addition, it appears that Hitler decided in September 1941 to proceed with the deportation of German Jews to Eastern ghettos and killing sites.

A final high-level signal of a change from a policy of deportation and expulsion to murder came with an October 18 notation in Himmler’s phone log: “No emigration by Jews to overseas.”14 Considering that Nazi policy to this point had sought to force Jews to leave Europe, preventing them from doing so indicates that emigration was no longer the Nazi course of action. Rather, Jews were to remain confined in Europe where they could be “resettled to the East,” a euphemism that would shortly come to mean “killed in mass gassing operations.” Indeed, by this time, rumors and insinuations were already flying. On October 23, a Nazi friend of Rademacher’s wrote him regarding a conversation with “an old party comrade, who works in the east on the settlement of the Jewish question.” This person apparently hinted that, “In the near future many of the Jewish vermin will be exterminated through special measures.” Historian Christopher Browning noted the “extraordinary coincidence” that on that same day, Adolf Eichmann met with his deportation experts concerning the deportation of German Jews.15 Table 7 notes some of the key moments that indicate the turn toward a full genocide against the Jews of Europe.

TABLE 7Final Solution decision and execution timeline.

Building the Apparatus of Death

One day in the winter of 1941 Wirth arranged a transport [of euthanasia personnel] to Poland. I was picked together with about eight or ten other men and transferred to Bełżec . . . I don’t remember the names of the others. Upon our arrival in Bełżec , we met Friedel Schwarz and the other SS men, whose names I cannot remember. They supervised the construction of barracks that would serve as a gas chamber. Wirth told us that in Bełżec “all the Jews will be struck down.”

—SS-Scharführer ERICH FUCHS16

The actual design and construction of what would become the extermination centers, like Bełżec, began in the late fall/winter of 1941. As Fuchs notes, these were purpose-built for murder. The first, Chełmno, became operational by December 8, 1941. Note that the term “extermination center” is used rather than concentration camp. While the Nazis murdered Jews and others in both places, the extermination centers served only as mass killing sites while concentration camps could also serve as punishment and slave labor locations.

There were four “pure” extermination centers: Chełmno, Bełzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. To these, we add the “hybrid” camps of Auschwitz and Majdanek, both of which operated as dedicated killing centers similar to the others; in Auschwitz, mass gassing occurred in several locations, eventually using four crematoria/gas chamber buildings in Auschwitz II (Birkenau). Majdanek repeatedly conducting mass killings, but they tended to be more sporadic. Bełzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka formed part of what became known as “Operation Reinhard” and were relatively similar, as we will discuss later. In July 1941, the mass killing apparatus had not yet been assembled.

The Nazis benefited, however, from distinct experiences that, when combined, would make the Final Solution possible. First, they had proficiency in the gassing of victims and disposal of bodies. This came from the Operation T-4 “euthanasia” program which had gassed 70,000 Germans. Moreover, many of those personnel involved were idle, as Hitler had been forced to “officially” end and decentralize the program. These experts were, therefore, available to assist in the design, building, and operation of extermination centers. Second, the Nazi state had perfected the concentration camp as a space of confinement and control. All that was lacking was the addition of a killing apparatus. Third, men like Adolf Eichmann and Franz Rademacher had gained invaluable experience in planning and coordinating the movement and deportations of large numbers of people by rail including Jews, Poles, and ethnic Germans. A further motivation for a change in killing methods was the very real mental damage being done to the Nazi killers, particularly those in the Einsatzgruppen. As the vast majority of these men were not sociopaths or insane, they suffered psychological damage approaching PTSD from the relentless murder of civilians, often regardless of how much they themselves approved or disapproved of the overall policy. Himmler himself had observed at least two mass shootings (August 15 and October 15, 1941).17 He was visibly upset and some witnesses claimed he vomited. In any case, after the August killing, he began issuing orders to find a less traumatic method of killing. At this event, the Higher SS and Police Leader, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski (who later suffered from PTSD himself) told Himmler: “Reichsführer, those were only a hundred . . . Look at the eyes of the men in this Kommando, how deeply shaken they are! These men are finished for the rest of their lives. What kind of followers are we training here? Either neurotics or savages!”18 A method of killing which distanced killers from their victims was clearly preferable. Further, throughout Eastern Europe, Jews were already conveniently confined in ghettos as the Nazis deliberated on their fate and capitalized on their labor.

However, even with all these helpful experiences, a good deal of improvisation and experimentation was still required to perfect the execution of the Final Solution. Across the Greater Reich, Nazi experts had already begun experimenting with different methods of murder. In September 1941, commander of Einsatzgruppe B, Arthur Nebe, requested the services of Dr. Albert Widmann, SS chemist and gassing expert from the T-4 program. Widmann arrived to assist in the murder of mental patients. Explosives were tried with unsuccessful results. An observer testified that “The sight was atrocious . . . Body parts were scattered on the ground and hanging in the trees.”19 Nebe then suggested the use of automobile exhaust (carbon monoxide) inspired by his own close encounter of passing out in a running vehicle in his garage after a night of drinking.20 This led to two tests involving exhaust pumped into sealed rooms from vehicles running outside.

At roughly the same time, in Berlin, Heydrich asked his technical chief of Department II-D, Walter Rauff, to investigate the feasibility of creating mobile gas vans. Rauff oversaw the conversion of a Saurer model cargo truck into a mobile gas chamber by sealing the cargo space and rerouting the exhaust gas. In late October/early November 1941, three chemists from the SS crime lab tested the gas vans in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, killing forty Russian prisoners.21 The SS commissioned the construction of thirty such “gas vans.”

The Chełmno extermination center relied solely on these vans. In November 1941, the chief of a mobile gassing unit, Herbert Lange, established a killing center in a local mansion there. He told his men that “absolute secrecy is crucial . . . We have a tough, but important job to do.”22 Victims from the surrounding area, and especially Łodz´, were trucked to the site where they entered the house, surrendered their valuables, and descended into the basement. Once in the basement, they undressed and climbed stairs leading into the back of a gas van. The van then drove a short distance into the forest where the driver attached the exhaust hose to the cargo compartment and waited until all Jews were dead. A Jewish Sonderkommando then unloaded and buried or burned the bodies. Among those murdered were also the Sinti/Roma (gypsies) who had been interned in the Łodz´ Ghetto. An SS man at Chełmno described the scene in the forest:

We could see a clearing in the forest and a gray van that was parked there with the rear doors open. The van was full of bodies, which were taken out by a Jewish labor squad and thrown into a mass grave. The dead people looked like Gypsies. There were men, women and children there.23

In this way, at least 152,000 Jews and Sinti/Roma were murdered between December 1941 and June/July 1944. There were four survivors.

In September 1941, SS officials began experimenting with Zyklon-B as an alternate form of gassing. Zyklon-B was a chemical agent used as fumigant to kill insects, particularly lice, in living areas, ship holds, and large amounts of clothing. When exposed to heat and humidity, it changed from a solid, pellet form to hydrogen cyanide gas. Zyklon B kills by preventing oxygen uptake in red blood cells, leading to suffocation. The first tests of this substance on humans occurred in Block 11 at Auschwitz on September 3, 1941 and three days later in a converted morgue space known as Crematorium I, where 900 Soviet prisoners of war were murdered. The commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss personally observed the testing and testified regarding these experimental killings at Auschwitz:

I must even admit that this gassing set my mind at rest, for the mass extermination of the Jews was to start soon, and at that time neither Eichmann nor I was certain as to how these mass killings were to be carried out. It would be by gas, but we did not know which gas and how it was to be used. Now we had the gas, and we had established a procedure.24

While Zyklon-B was famously used at Auschwitz and Majdanek, all other extermination centers used carbon monoxide gas generated from vehicle engines, often from submarines, tanks, or trucks.

Himmler commissioned the odious Higher SS and Police Leader in the Lublin District of the General Government, SS-Brigadeführer Odilo Globocnik, with the construction of the killing centers in Poland that would later be named Operation Reinhard after Heydrich’s assassination in May 1942. Operation Reinhard encompassed the eventual construction of Bełzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. Globocnik and his staff identified suitable locations for these camps and oversaw their construction. In order to avoid the public nature of the Einsatzgruppen killings, these extermination centers were located away from major population centers but on key railroad lines, allowing easy deportation of Jews to the camp by train. We will examine one camp, Treblinka, in more detail.

Globocnik also needed staff for the Operation Reinhard camps and found a ready pool of capable men in the former members of the T-4 program. Viktor Brack, who had organized the T-4 killing operations, testified at his trial that:

In 1941, I received an order to discontinue the euthanasia program. In order to retain the personnel that had been relieved of these duties and in order to be able to start a new euthanasia program after the war, Bouhler [a co-conspirator in the T-4 program] asked me-I think after a conference with Himmler- to send [these] personnel to Lublin and place [them] at the disposal of SS Brigadeführer Globocnik.25

The unemployed T-4 men heeded the call. They “compose[d] almost the entire personnel of the extermination camps of Operation Reinhard.” At least ninety worked in Bełżec , Sobibor, and Treblinka.26 These men brought with them the experience of managing and working in gassing facilities and disposing of large numbers or bodies. The move to extermination was hardly a stretch.

On January 20, 1942, an important meeting took place in a villa on the idyllic Wannsee Lake outside Berlin. Reinhard Heydrich had originally scheduled the meeting for December 8, 1941, but more pressing events such as a Soviet counter-offensive and the American entry into the war forced a change of date. This daylong meeting became known as the Wannsee Conference and had important repercussions for the implementation of the Final Solution. Contrary to popular belief, the conference sought not to decide on the Final Solution, but rather to coordinate all the government offices in the task of carrying out the mass murder of Jews. As we have seen, the decision to kill, the methods, and the locations had already been agreed upon. Indeed, while the attendees met in an ornate dining room, some of the extermination centers to which they would send Jews to be murdered were already being built. The meeting was important enough, however, to require the presence of high-level Nazi officials and was led by Himmler’s right-hand man, Reinhard Heydrich. The fifteen attendees represented the government departments who would be most involved in the deportation and murder of Jews. Some notable attendees were:

•Heinrich Müller, chief of the Gestapo

•Adolf Eichmann, head of RSHA office IV-B-4, deportation expert

•Dr. Rudolf Lange, former leader of Einsatzkommando 2 in the Baltic

•Dr. Eberhard Schöngarth, former Einsatzkommando leader in Galicia and then Commander of Security Police and SD in the Generalgovernment

•Dr. Josef Bühler, deputy of Hans Frank, Governor of the Generalgovernment27

These men gathered in the villa for approximately an hour and a half. Heydrich had appended to the initial November 29, 1941, invitation his authorization from Göring to plan the Final Solution, presumably to clearly establish his authority at the table.28 Only one copy of the minutes of the Wansee Conference survived, and it lays out in detail the topics of discussion and outcomes of the meeting. After a brief summary of previous actions against the Jews, the minutes note that Hitler had given his approval for the “evacuation of the Jews to the East,” a euphemism which stood for mass murder. The next page contained estimates of Jewish populations to be exterminated (including in yet-to-be-conquered countries such as England and Ireland). The population of Jews to be murdered was estimated at 11 million. The fate of “mixed race” Jews (Mischlinge 1st and 2nd Class) was also settled. The majority of Mischlinge 1st Class was to be killed while the majority of the Mischlinge 2nd Class was not. Indeed, it appears that a substantial amount of time was devoted to this issue and possible exceptions. The meeting minutes concluded with a recognition of SS authority in the Final Solution and the pledged support of the government agencies in attendance.29 On January 31, 1942, SS deportation expert Adolf Eichmann sent a memo to SS authorities in Germany and Austria, instructing them to prepare for the “beginning of the Final Solution” and the “evacuation” of German and Austrian Jews.30 By this time, gassing had already begun at Chełmno and would begin with months at Bełzec, Auschwitz, and Sobibor. Thus, at all levels—from methods to personnel to bureaucracy—the Nazi state had committed itself to a program of mass murder and genocide.

“The Terrible Smallness of the Place”: Inside Treblinka31

“Here no one remains alive,” he said. “Pray for them.” Then we knew.

STANISLAW SZMAJZNER, Treblinka survivor32

The Treblinka extermination center fifty miles northeast of Warsaw serves as a good example of the history of the Reinhard camps and as a vehicle through which to examine in detail the most deadly of them. The Nazis murdered between 870,000 and 925,000 Jews in the sixty acres that constituted the camp.33 For inmates of the camp, like Stanislaw, the inconceivable magnitude of the crime taking place there became clear by way of initiation to their new surroundings. Treblinka ranks second only to Auschwitz in numbers of Jews murdered. In many ways, it represents the pinnacle of achievement for planners of the Final Solution, surpassed only by the later crematoria complexes of Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

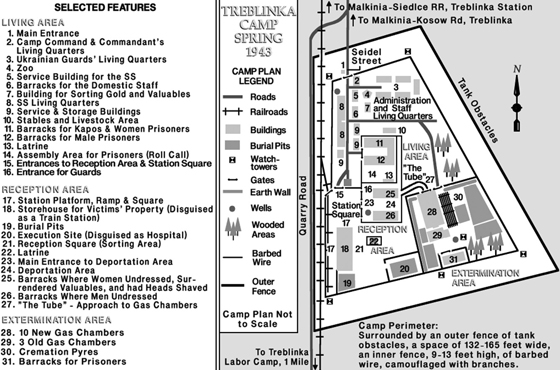

FIGURE 19Map of the Treblinka Extermination Center

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The construction of the Treblinka extermination camp began in May 1942, likely upon the personal order of Himmler who had visited the Higher SS and Police Leader in Warsaw, Arpad Wigand, on April 17, 1942. Labor was provided by the nearby Treblinka I slave labor camp (the extermination camp would officially be named “Treblinka II,” but we will use Treblinka as a shorthand here). The work was supervised by two German construction firms. The future commandant, Dr. Irmfried Eberl, a T-4 veteran, and 30–40 SS men, arrived as well. They were accompanied by 90–120 “Trawniki” men, Ukrainian guards recruited from German camps for Soviet POWs.34

The camp itself was divided into three sections: Camp I- the reception Area, Camp II- the “death camp” with gas chambers and burial sites, and Camp III- the living quarters for the SS and Ukrainians as well as barracks and workshops for the small contingent of Jews kept alive to help run the camp and craft items for the SS. The camp underwent renovations and upgrades, including the construction of a larger gas chamber complex, but its layout and function would remain mostly the same. A rail line was built off the main route so that trains could directly enter the camp. This area would later be improved into a “ramp,” complete with a fake train station. This rail spur could accommodate twenty freight cars at a time, though frequently the trains arriving were 50–60 cars long, carrying around 5,000 people. These trains were simply broken up and twenty cars were then backed in by a Polish engineer who was forbidden to enter the camp.

Once on the ramp, the trains unloaded in front of the fake train station in order to deceive the victims as long as possible. This was at least partially effective. As one survivor, Richard Glazar, recalled, “I saw a green fence, barracks, and I heard what sounded like a farm tractor. I was delighted.”35 Arriving Jews would leave their baggage, be separated by sex, and be led into the reception area of Camp I. Children generally stayed with their mother. They undressed, and camp prisoners shaved all body hair for later use in the German economy. An SS memorandum from August 1942 explicitly stated that men’s hair would be used to create “industrial felt” and women’s hair would become “liners and socks for U-boat crews and railway workers.” Camps were to report the total amount of men’s and women’s hair on the fifth of each month.36 All currency and valuables were surrendered here as well. Next, a selection took place in which a few new arrivals (and often none) were selected to work in the camp. Those unable to move were taken away. The SS guard responsible, Willi Mentz, described this job: “There were always some ill and frail people on the transports . . . These ill, frail, and wounded people . . . would be taken to the hospital area. When no more ill or wounded were expected it was my job to shoot these people. I did this by shooting them in the neck with a 9mm pistol.”37 SS and Ukrainian guards then drove able-bodied victims down a barbed-wire corridor, camouflaged with branches, leading to the gas chamber complex. This corridor was known as “the Tube” or “Road to Heaven.” At the end, climbing a few stairs, they would enter a long central corridor with ten gas chambers, five located on either side. Once the chambers were filled, the SS would start two tank engines that pumped carbon monoxide gas through pipes and out fake showerheads in the gas chambers. It took approximately 20 minutes for victims to suffocate.

After all had died, the Jewish squad (Sonderkommando) responsible for clearing the bodies began their work. Through larger exterior doors, they untangled and removed the bodies. Prisoners also were forced to remove gold teeth from the corpses, which were initially buried in large pits. Later, when numbers became too great, the bodies were exhumed and burned on long railroad ties, forming a sort of grill and referred to as “roasts.” Other members of this group were responsible for cleaning the gas chambers in preparation for their next use. A former commandant of the camp, Franz Stangl, testified that “when the gas chambers were running for fourteen hours, approximately 12,000–15,000 people could be disposed of.” He added that “there were many days when we worked from morning to evening.”38

Between 750 and 1,500 Jewish prisoners worked in the camp at any given time, divided into groups based on the labor they carried out. The most privileged group was the craftsmen, who ran small workshops for the SS. The “Water Kommando” lived and worked solely in the killing section, Camp II, and was segregated from the rest of the prisoners. There was a “Blue Kommando” who met the transports upon arrival and cleared the ramp area of their possessions. The “Red Kommando” included SS men and operated in the Reception Area (Camp I) overseeing the undressing of victims, sorting of the clothes, selections of those unable to walk to the gas chambers, and their execution in the so-called Hospital. The “Rag Kommando” sorted clothing by quality and searched for any hidden valuables. Lastly, the “Camouflage Kommando” was responsible for the constant refreshing of the branches that covered the camp’s fencing, including the “Tube” to the gas chambers.39

The first commandant, psychiatrist Dr. Irmfried Eberl, epitomized the connection between the Final Solution and the T-4 program, as he had formerly been the director of the Brandenburg and Bernburg “euthanasia” centers in Germany before being assigned to Treblinka. However, the task of running the extermination center appears to have exceeded Eberl’s abilities and the camp rapidly spun out of control. Odilo Globcnik, the man responsible for the Reinhard camps, discovered Eberl’s incompetence and the lack of valuables being sent on from the camp. On August 28, 1942, he reassigned the commandant of the Sobibor killing center, Franz Stangl, to relieve Eberl and assume command of Treblinka. Ironically, Eberl had been Stangl’s superior at the Bernburg T-4 killing hospital. Stangl described his first visit to Treblinka in a 1971 prison interview. “It was Dante’s Inferno,” he said, “I waded in notes, currency, precious stones, jewelry, clothes. They were everywhere, strewn all over the square. The smell was indescribable; the hundreds, no, the thousands of bodies everywhere, decomposing, putrefying.”40 Eberl was unceremoniously returned to the Bernburg hospital. Shortly thereafter, Stangl streamlined operations in the camp and created a more disciplined environment there. By all accounts, he was a conscientious and efficient commander. He himself stated, “That was my profession; I enjoyed it. It fulfilled me. And yes, I was ambitious about that; I won’t deny that.” Stangl coldly divorced himself from the horror of his “profession.” Jews became “cargo” or a “huge mass” to him.41 He also avoided visiting the gas chambers as much as possible. Stangl was transferred in August 1943 after a prisoner revolt in the camp and was sent to fight partisans in Italy.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Gassings continued for a short while in the camp under Stangl’s deputy, Kurt Franz, before the killing stopped in October 1943. The Nazis razed the camp, planted trees, and installed a Ukrainian family in a farmhouse on the site. During the sixteen months the camp was in operation, between 750,000 and 900,000 Jews had been murdered, including over 250,000 from the Warsaw ghetto. During the period of that ghetto liquidation, the camp averaged 5,000 arrivals a day.42

Auschwitz: The Apex of the Final Solution

Prominent guests from Berlin were present at the inauguration of the first crematorium in March 1943. The “program” consisted of the gassing and burning of 8,000 Cracow Jews. The guests, both officers and civilians, were extremely satisfied with the results and the special peephole fitted into the door of the gas chamber was in constant use. They were lavish in their praise of this newly erected installation.

RUDOLF VRBA and ALFRED WETZLER, Auschwitz survivors43

For both the Nazis, like the prominent guests mentioned above, as well as the modern public, Auschwitz more than any other place, perhaps, serves as the public face of the Holocaust. But it is deserving of a brief discussion here not because of its notoriety, but because of the way in which it combined or represented most of the facets of the Nazi genocidal project and the Holocaust in the East that we have discussed in this book. Nazi planners envisioned transforming the town of Oswieçim (Auschwitz) into a model of German settlement and agricultural achievement. The camp itself was not to be a blemish on this exhibition of German superiority but a model of success; Himmler himself planned an apartment in the town. The commandant of the camp remembered Himmler’s plans for the camp: “Every necessary agricultural experiment was to be attempted there. Massive laboratories and plant cultivation departments had to be built.”44

The camp itself was simultaneously a prison to “convict” and punish political opponents, primarily Poles. It became a massive slave labor camp and the hub of many subcamps whose mainly Jewish labor was intended to support the Nazi state. It contained its own factory complex of the massive Nazi conglomerate I. G. Farben. And, finally, it served as the largest and most deadly of the centers for the extermination of Jews, a place where the process was perfected, streamlined, and constantly being improved. Compared to Treblinka, only 60 acres in size with a combined SS/Ukrainian staff of less than 200, Auschwitz was immense. It covered a territory of 9,600 acres with a staff of over 7,000. The Auschwitz camp was a product both of the Nazi imagination of the East and its conquest, and the accompanying genocidal project, directed first and foremost against the Jews.

The site itself began as a Polish Army camp, first noticed by the future Higher SS- and Police Leader, Bach-Zelewski on a search for concentration camp sites in January 1940. The former ammunition depot would become the future first gas chamber. The Army, who controlled all Polish military installations, handed the area over to the SS and on April 27, Himmler decided that a concentration camp would be built there.45 Three days later, the thirty-nine year old new commandant, SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Rudolf Höss arrived. He was described later as looking like “a normal person, like a grocery clerk.”46 After an apprenticeship at the Dachau concentration camp in Germany, Höss came to Poland believing that “true opponents of the state must be locked up.”47

But the site at Auschwitz was in no way ready to be the iconic site of evil it would become. Höss lacked the most basic materials to create a prison camp. He candidly recalled that, “Whenever I found depots of material that was needed urgently I simply carted it away without worrying about the formalities. I didn’t even know where I could get a hundred meters of barbed wire. So I just had to pilfer the badly needed barbed wire.”48 In short, Auschwitz was built, at least initially, out of stolen property. Höss worked dutifully, and was prepared to receive the first prisoners in June 1940 who were neither Polish nor Jewish, but German career criminals who would become the first kapos or overseers of the camp’s prisoners. The old Polish army portion of the camp (known as Auschwitz I) soon received large numbers of Polish political prisoners. As mentioned, gassing experiments took place in Block 11 but soon the crematorium in Auschwitz I was converted into a gas chamber/crematorium.

The scope of the planning for Auschwitz broadened throughout 1941. In October, construction began on a much larger camp a few kilometers from Auschwitz I, which would come to be known as Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Himmler’s notes state that it was intended to hold up to 100,000 Soviet POWs. However, this massive new camp soon came to hold predominantly Jews and the extermination apparatus. The barracks were made up predominantly of pre-fabricated German Army horse stables designed to hold 52 horses; SS planners determined that they would hold 774 prisoners.49 Finally, in October 1942, a factory slave labor camp called Auschwitz III-Monowitz was built by camp labor for the I. G. Farben corporation to manufacture synthetic rubber. Primo Levi would be an inmate in this section of the camp.

In March 1942, Jews arrived in Birkenau as the first prisoners. By this time, a small farmhouse known as Bunker 1 or the “Little Red House” had been modified into a gas chamber with a capacity of 800 and was used to murder non-working Jews from the surrounding areas. By July 1942, the first selections of a transport of Slovakian Jews were gassed on arrival in Bunker 1 and in a second converted cottage known as Bunker 2 or the “Little White House.” This marked a transition to systematic killing at Auschwitz. It was not, however, without its problems. There were as yet no crematoria, so bodies had to be burned in the open, which was slow, dirty, and difficult to conceal. Throughout the summer of 1942, men like Theodor Dannecker, then posted in France, arranged the deportation of thousands of western European Jews to Auschwitz.

On August 10, 1942, work began on the gas chambers and crematoria that would make Birkenau infamous. Existing plans for massive ovens to be built as morgue and crematoria complexes were modified, with the addition of undressing rooms and gas chambers, to become self-contained killing locations. Eleven German civilian companies participated in the building of Auschwitz’s killing infrastructure, from furnaces to chimneys to waterproofing to roofing to ventilation systems to electrical wiring.50 All knew precisely the purpose of the buildings they were constructing. Ultimately, four crematoria were constructed (II-V). The gas chambers could accommodate 2,000 victims at a time. Three to five bodies could be burned simultaneously in one oven over the course of thirty minutes. 2,500 corpses could be burned per day in Crematoria II and III and 1,500 per day in Crematoria IV and V. However, the Nazis still faced the dilemma of body disposal as the limiting factor on killing capacity and tempo. More victims could be killed than could be cremated. Thus, when the camp was running at full capacity, murdering 9,000 Jews a day, the ovens could not keep up, leading to open-air burning as a supplementary measure.51

In March 1943, the first of the crematoria (II) opened at Birkenau and began the mass extermination of Jews at Auschwitz. Prisoners arrived via train outside of Birkenau and walk a short distance into the camp where, after a brief selection, the majority would be directed to one of four crematoria where, in the case of Crematoria II and III, they would undress in an underground room and then proceed into the gas chamber, which had a capacity of 2,000. An SS man wearing a gas mask then walked along the roof of the gas chamber, pouring Zykon-B pellets into mesh columns down into the chamber. The pellets aerosolized and asphyxiated the victims. Next, as in the Reinhard camps, prisoners of the Sonderkommando removed the bodies to the furnaces to be burned, clean the chambers, and prepare for the next arrival. Other camp Jews collected and sorted clothing and belongings of the victims with currency and precious metals being turned over to the guards for deposit in SS coffers. Camp architects built the iconic “ramp” and railroad tracks running directly into the camp in preparation for the murder of Hungarian Jews. In the summer of 1944, deportation expert Adolf Eichmann arranged for the transporting of approximately 400,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, where most were gassed upon arrival. Gassing at Auschwitz ended in November 1944 and the gas chambers and crematoria were demolished by the Nazis a day before the camp’s liberation by the Soviets in January 1945.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Ghetto Liquidations and the Attempted Destruction of Evidence

I order that all Jews still remaining in ghettos in the Ostland area be collected in concentration camps . . . Inmates of the Jewish ghettos who are not required are to be evacuated to the East.

Himmler order, June 21, 194352

More than 12,000 bodies were taken out—men, women, children. These bodies were piled up together, 300 at a time, to be burned. What was left after the burning (charcoal and bones) was ground down to powder in pits. This powder was then mixed with earth so that no trace of it should remain.

Collective statement by escapees from Sonderkommando in Kaunas, Lithuania, December 26, 194353

Ghettos throughout Eastern Europe constituted one of the major sources of victims for the extermination centers. They had already suffered a “Second Wave” of killings as the Nazis continued to reduce the populations to only those Jews capable of working or otherwise supporting the war effort. After several high-profile acts of resistance, the Nazis became increasingly uncomfortable with maintaining large populations of increasingly well-informed Jews. This was one of the reasons for Himmler’s directive above and the so-called Third Wave of killings that eliminated almost all of the ghettos in the east, with the exception of small numbers of laborers and a few ghettos converted into short-lived concentration camps. Another reason for the final liquidation of ghettos in the east was the increasingly desperate nature of the war and the accelerating German retreat. SS officials wished to finish their task and also leave no witnesses. This program of mass killings, too, represents part of the Final Solution.

Depending on date and location, some ghettos were liquidated through multiple Aktions and deportations to the killing centers. This was the case particularly for the largest Polish ghettos of Łodz´, Warsaw, Lublin, and Lwów, as well as those in other large cities such as Budapest. Most of the mass deportations had taken place in the summer of 1942. Table 8 above shows some of the deportations from the larger cities.

TABLE 8Major deportation Aktions to killing centers in the East.

|

Date |

Location |

Approximate Number |

|

January–September 1942 |

Łodz´ |

70,000 |

|

March–April 1942 |

Lublin |

34,000 |

|

July–September 1942 |

Warsaw |

265,000 |

|

August 1942 |

Lwów |

65,0000 |

|

October 1942 |

Krakow |

6,000 |

|

February 1943 |

Bialystok |

10,000 |

|

March 1943 |

Krakow |

3,000 |

|

August 1943 |

Bialystok |

7,600 |

|

May–July 1944 |

Budapest |

440,000 |

|

August 1944 |

Łodz´ |

75,000 |

Of course, some smaller ghetto populations were liquidated in the gas chambers, such as the last 3,500 Jews of the town of Lida in Belarus—who were sent to the Sobibor killing center on September 18, 1943.54 However, the majority of the last killings in the East took the form of the first killings. Most ghettos were liquidated through mass shooting operations. The town of Peremyshliany in Ukraine is a good example. Some of its Jews were sent to Bełzec in 1942. However, that extermination center had closed by May 22–23, so German Police Regiment 23 and the Ukrainian Police murdered the remaining 2,000 Jews in the ghetto and in the surrounding forest.55 Throughout the East, small ghetto populations were murdered, with only a few survivors who either escaped or were sent to various concentration camp systems. Importantly, however, many of these ghetto liquidation operations met with fierce resistance by the remnants of the surviving Jewish populations.

TABLE 9Closing of extermination centers.

|

Date |

Camp |

|

December 1942 |

Bełzec |

|

March 1943 |

Chelmno (1st closing) |

|

August 1943 |

Treblinka |

|

November 1943 |

Sobibor |

|

May 1944 |

Majdanek |

|

June 1944 |

Chelmno (2nd closing) |

|

January 1945 |

Auschwitz |

The closing of the extermination centers and the liquidation of the ghettos ushered in the last phase of the Final Solution: the eradication of the evidence. This operation, Operation 1005, was carried out across the occupied East by multiple squads known as Sonderkommando 1005. The Nazis had murdered almost six million Jews throughout Eastern Europe and had left many mass graves behind. As early as February 1942, a Foreign Office official wrote Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo, concerning an anonymous report of mass graves being discovered in occupied Poland. Müller nonchalantly dismissed these concerns, saying “In a place where wood is chopped splinters must fall, and there is no avoiding this.”56 However, in June, Müller tasked former Einsatzkommando leader, SS-Standartenführer (Colonel), Paul Blobel, with eradicating any traces of the Final Solution in Eastern Europe. Rather than beginning with the mass graves he was most familiar with, Blobel started unearthing, burning, and reburying the ashes of victims at the extermination centers, beginning with Chełmno. He then visited Auschwitz, advising the commandant on how best to dispose of corpses that had not been burned in the early period of the camp. Blobel’s Sonderkommando 1005 units then spread out to work in the other extermination centers. The camps were leveled and trees planted to forever hide their existence.

After the mass graves in these camps had been disposed of, the Sonderkommando 1005 staff faced the much larger and more difficult task of the identifying and clearing of thousands of mass shooting sites across the occupied Soviet Union. Blobel first began work on the mass graves of the Janowska camp in Lwów, Ukraine. SS-Unstersturmführer (Second Lieutenant) Walter Schallock, a man described as “always drunk but never rowdy . . . shrewd and an excellent administrator” commanded local operations.57 Policemen from the 23rd Police Regiment were allocated as additional manpower. These men had to sign a document swearing them to secrecy.58 Killings continued at the site as Schallock and 129 Jewish prisoners from the camp began the gruesome task of unearthing the bodies, burning them, grinding any remaining bones into dust, searching for any valuables remaining, and then reburying the ashes. The Sonderkommandowas divided into different squads for these various tasks. Survivors of the SK1005 group in Janowska recalled their awful work in postwar statements. Heinrich Chamaides described the process: “We laid a layer of wood between each layer of bodies and then soaked it in old oil and gas. When the bodies were burned, we ground the bones to ashes and spread the ashes on the fields. While the bodies burned, an orchestra played.”59 Another survivor, Moische Korn, recalled recognizing the body of his own wife. He asked Schallock to shoot him; Schallock replied that “I would remain alive as long as I was needed and as long as I could work. Then [Schallock] forced me to throw the body of my wife into the fire.”60 The SS men even dressed up a prisoner in a hat with horns, called him “the Devil,” and placed him in charge of keeping the fires burning.61 Frequently, groups of future SK1005 SS men would visit the camp. A member of the Sonderkommando at Janowska recalled that “10 day special courses” were held in the SK for officers and sergeants. There they learned how to exhume and burn bodies, disguise the gravesites, and bury any remaining evidence. He recalled at least ten such courses.62 Some members of the SK1005 at Janowska escaped and survived, but in most places in the East, the Sonderkommando Jews were murdered immediately upon completion of their tasks.

The “Final Solution,” the physical extermination of the Jews, evolved as a series of developments affected by time and situational factors; yet, at the same time, it was driven from the beginning by the ideological dedication of the Nazis to removing Jews from society. As we have seen, it was the method of removal that changed from expulsion to extermination over the course of the war. In many ways, the Final Solution—as it was carried out in the extermination centers—represents the unholy combination of a state political system with industrial methods and pseudoscientific theories. The Nazis created a streamlined process capable of murdering horrifyingly large numbers of human beings in a relatively efficient manner.

TABLE 10Extermination centers and their death tolls.

|

Killing Center |

Number of Victims |

|

Auschwitz |

1,100,000 |

|

Treblinka |

870,000–925,000 |

|

Bełzec |

434,500 |

|

Sobibor |

170,000 |

|

Chełmno |

152,000 |

|

Majdanek |

78,000 |

Source: Numbers from USHMM with the exception of Majdanek whose numbers are from Tomasz Kranz, “Ewidencja zgonów i śmiertelność więźniów KL Lublin,” Zeszyty Majdanka 23 (2005).

However, it is also important to remember that 1.5–2 million Jews were killed in open-air shootings as part of the Final Solution, and that thousands died of disease, starvation, and maltreatment before and after the decision to physically exterminate the Jews.

The Nazis were most successful at this task in Europe, but the genocide known as the Holocaust had no geographic limits. It is, therefore, important to recognize that there were Einsatzgruppen allocated to Rommel’s “chivalrous” Afrika Korps in North Africa, and that the Wannsee Conference targeted Jews outside Europe. We must also remember that the majority of Western European Jews murdered during the Holocaust were killed in the extermination centers of the East. These facilities were located there not because Eastern Europeans were more antisemitic than those in the west, but because the majority of the victims (ca. 5.6 million) were there.

Selected Readings

Arad, Yitzhak. Bełżec , Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Browning, Christopher R., and Jürgen Matthäus. The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Montague, Patrick. Chełmno and the Holocaust: The History of Hitler’s First Death Camp. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Rees, Laurence. Auschwitz: A New History. New York: Public Affairs, 2005.

Sereny, Gitta. Into That Darkness: An Examination of Conscience. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.